At Sayburç in southeastern Turkey, a few miles from the world-famous megalithic site of Gobekli Tepe, a very ancient engraved stone panel was excavated in 2021. The panel shows, from left to right, a charging wild bull, a man holding a serpent sitting or falling back before the bull, and a seated man holding his penis and flanked by two leopards.

After our flight to Istanbul took off from Baghdad International Airport I opened my laptop and re-read a research paper on the panel by Turkish archaeologist and art historian Dr Eylem Özdoğan. Titled The Sayburç reliefs: a narrative scene from the Neolithic, the paper, was published in the authoritative peer-reviewed journal Antiquity in 2022 and contained a photograph of the eponymous scene which is carved into the vertical aspect of a knee-high stone bench. Dated to around 8500 BC, the scene has the “narrative integrity of both a theme and a story in contrast to other contemporaneous images,” says Dr Özdoğan. Indeed in her view it “represents the most detailed depiction of a Neolithic ‘story’ found to date in the Near East, bringing us closer to the Neolithic people and their world.”1

In the same folder where I’d filed Dr Özdoğan’s paper I’d filed the high-resolution photograph of the complete panel which the photographer, B. Kosker, had kindly released on Creative Commons:2

Photo B. Kösker (CCBY4.0)

The scene seemed naturally divided into two parts so I had also made cropped versions of each “part”, as follows:

Photo B. Kösker (CCBY4.0)

Photo B. Kösker (CCBY4.0)

Before boarding our flight to Turkey my wife Santha and I had spent two weeks in Iraq, homeland of ancient Sumer, the world’s first literate civilization. Our primary purpose had been to visit the sites of ancient cities associated with the Sumerian Deluge legend.3 Paramount amongst these was Uruk with its origins dating back to 4000 BC or earlier, its great Ziggurat dedicated to the sky god Anu and it’s starring role in the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh which itself contains a substantial discourse on the Deluge. I’d therefore been reading a good English translation of the epic along the way.4 Perhaps this was why a seemingly mad question suddenly began to clamour for my attention as I studied the photographs. Could the Sayburç reliefs have served as visual aids – a Neolithic version of PowerPoint slides – to accompany the recitation of an earlier unwritten incarnation of the story that we now know as the Epic of Gilgamesh?

What the Sayburç reliefs definitely don’t depict are simple hunting scenes. No hunter would take time out to masturbate while flanked by two snarling leopards – an “indifferent stance” as Özdoğan puts it, in the face of danger.5 And while wild bulls – aurochs in those times – were indeed hunted, a wall painting from the younger (7500 BC) site of Çatalhöyük shows the end of a hunt with an auroch subdued by a large number of armed men. Moreover, the creature is depicted as already dead, its tongue protruding, and thus no longer posing any threat. By contrast, observes archaeologist Jens Notroff, these are characteristics we do not find at Sayburç:

There, apparently, we see a still living animal, a still dangerous bull. At Sayburç we see a confrontation. Which leaves the question: What is the person actually doing here? Just like in case of the aurochs, its posture suggests dynamic and motion. Almost like an interaction — cocked legs as if the person is trying to dodge the approaching animal.6

Notroff hopes that the reliefs might help archaeologists better interpret Neolithic iconography in Turkey but adds:

Unfortunately, while the Neolithic hunter may have easily recognized its message we are still lacking an understanding of the actual narrative.7

In her Antiquity paper on the Sayburç reliefs Dr Eylem Özdoğan faces the same challenge. “The figures were undoubtedly characters worthy of description,” she writes:

The fact that they are depicted together in a progressing scene, however, suggests that one or more related events or stories are being told. In oral traditions, stories, rituals and strong symbolic elements form the foundation of the ideologies that shape society beyond spirituality.8

So maybe my mad idea wasn’t such a big leap? Dr Özdoğan had already put peer-reviewed authority behind the conclusion that the panel included a scene or scenes from an ancient story of some kind. But, like Notroff, she did not venture a guess as to which story it might have been. Gilgamesh had seemed unlikely to me at first because of the gap of more than 6,000 years between the Sayburç panel (around 8500 BC) and the earliest-surviving written recensions of the epic (around 2000 BC). But as I gave more thought to the matter, I realised that those six millennia didn’t necessarily represent an unsurmountable obstacle. After all, 3,000 years have passed since the time of Homer but the Odyssey (itself originally an oral not a written tale) is still being retold – for example in the 2024 film The Return.9 Meanwhile studies amongst Australia’s First Nations peoples and amongst the Kootenay of Oregon in the United States have proved that oral traditions still in circulation today accurately record and preserve information of significantly greater antiquity than Homer. Patrick Nunn, Professor of Geography at Australia’s University of the Sunshine Coast, summarises the conclusions of this research:

Under optimal conditions, as suggested by science-determined ages for events recalled in ancient stories, orally shared knowledge can demonstrably endure more than 7,000 years, quite possibly 10,000…10

There is, therefore, no a priori reason why the Epic of Gilgamesh shouldn’t be much older than its oldest-surviving written recensions, no reason why it shouldn’t have begun life around 8500 BC, the date of the Sayburç reliefs, no reason why it shouldn’t already have been ancient when the reliefs were made, and no reason why the story behind the reliefs should have been confined to the Sayburç area. Ancient communities were not hermetically sealed and Sayburç stands close to the headwaters of the Euphrates River just a few hundred kilometres from the borders of ancient Sumer where the Epic of Gilgamesh was supposedly “composed”. The possibility of a connection can’t be ruled out.

Pressure of other work meant that I didn’t see Dr Özdoğan’s 2022 paper on the Sayburç reliefs until the latter half of 2023 and it wasn’t until 2024 that I used my blog to set out my own first thoughts about the reliefs.11

What struck me most forcefully at the time was not only that this panel is indeed a contender for the role of the earliest-known depiction of a narrative scene, as Dr Özdoğan contends, but also that it is, unequivocally, the earliest-known depiction of a motif known as the “Master of Animals” that would become prevalent across vast expanses of the ancient world as far afield as Egypt and Peru, from about 6,000 years ago.

This very distinctive motif typically shows a man threatened by fierce animals, often felines such as lions and leopards, but sometimes by other wild creatures as well. In every case the individual at the center of the scene seems relaxed, unafraid and in complete control — hence “Master of Animals”.

As such the Sayburç scene looked to me – and continues to look — like a potentially fruitful link between prehistory and history, between those unnumbered aeons when it seems that nothing was written down and the last 6,000 years or so that have been dominated by the written word.

Sayburç, Karahan Tepe and Boncuklu Tarla

Only in May 2025, at the end of our research trip across Iraq, were Santha and I finally able to get to Sayburç. After flying from Baghdad to Istanbul we caught a domestic Turkish Airlines connection to Sanliurfa, the bustling capital of the region in which Gobekli Tepe, Sayburç and other extremely ancient megalithic sites are located.

The next day, Thursday 15 May 2025, we drove the short distance from Sanliurfa to Sayburç and found the site deserted. The northern sector, including the house beneath which the narrative panel had been excavated, was closed and fenced with “no-entry” signs prominently displayed. We did not attempt to enter. The southern sector was not fenced and a series of excavation pits, protected by low aluminium roofs, revealed circular enclosures and T-shaped megalithic pillars in the characteristic style of Gobekli Tepe.

Even to my non-specialist eye, however, it was obvious that nothing on the scale of the two largest and oldest pillars at Gobekli Tepe (around 9600 BC, in Enclosure D) had yet been found at Sayburç where the “special buildings and reliefs” have been dated to approximately 8500 BC12, contemporary with the final but not the early phases of Gobekli Tepe. Indeed, as Dr Özdoğan points out, Sayburç demonstrates an unmissable continuity of architectural traditions and related symbolism “from as far back as the mid-10th millennium BC, as evidenced by Gobekli Tepe and Karahan Tepe… until the mid-9th millenium BC.”13

Nor is it likely that the trail of continuity simply “begins” in the 10th millennium BC. On the contrary it has been convincingly argued that Gobekli Tepe and Karahan Tepe were themselves the evolved products of an even older architectural tradition that becomes archaeologically visible in this area in the 11th millennium BC (i.e. between 13,000 and 12,000 years ago) some 200 kilometers to the east of Sayburç at the site of Boncuklu Tarla.14

“Pillar Building”, Boncuklu Tarla, dated to approx. 10,200 BC, six hundred years older than Enclosure D at Gobekli Tepe. Photo Santha Faiia.

Over the past decade, unlike its predecessor Boncuklu Tarla, Gobekli Tepe has been transformed into a tourist Disneyland, only token excavations continue there, and the megaliths, amongst which the late, great Klaus Schmidt allowed us to wander freely on our first visit in 2013,15 must now be viewed from afar.

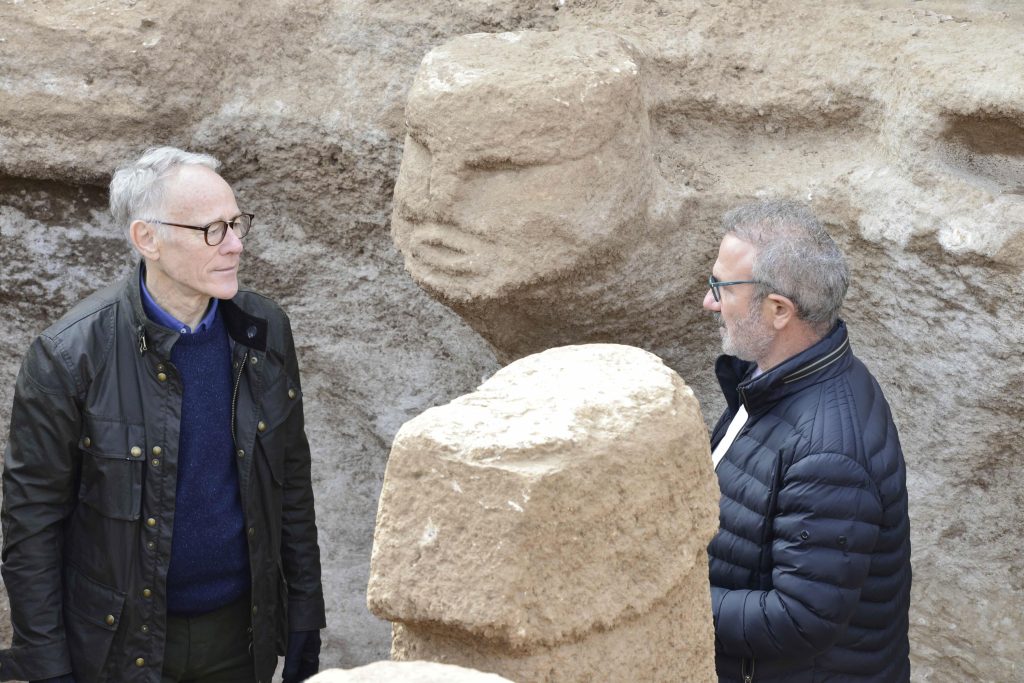

After seeing what we could at Sayburç, therefore, Santha and I bypassed Gobekli Tepe and drove directly through the stony, windswept hillscapes to Karahan Tepe which is still under active investigation and where enclosures that had been buried during our previous visits had now been revealed thanks to several seasons of excavations undertaken by a team from the University of Istanbul led Professor Necmi Karul.

The numerous excavation pits that now confronted us were by no means the only obvious changes. Although on a less-ambitious scale than Gobekli Tepe, a visitor centre and café had been set up, pilings for the pillars that would support a roof over the site were already in place, and tourist buses arrived at regular intervals. Still, there were gaps when no-one showed up and we had Karahan Tepe to ourselves, just as we had when we first came here in 2014 before any excavations had begun.16

We’d returned in December 2020 when I’d interviewed Professor Karul at the site for my Netflix Documentary series Ancient Apocalypse. We’d talked amidst a group of obviously phallic stone pillars rising up from the floor of a semi-subterranean chamber entirely hewn out of bedrock and overlooked by a protruding human face, with something eerily snakelike about its neck, also carved from the bedrock.

“It looks like the snake head,” commented Professor Karul. “It behaved like a snake.”

“A human-headed snake?” I replied.

“Yeah, maybe,” allowed Karul.

“It’s a kind of unique discovery?”

“Yeah, it’s fantastic.”

Now, in 2025, much more of Karahan Tepe, and many more fantastic things, had been revealed by Professor Karul and his team including a striking monolithic statue of a male figure seated on a rock-hewn bench in a large enclosure flanked by shattered T-shaped pillars.17

I will not give an extensive written description of the statue here, since Santha’s photographs do it far better justice than words alone ever could. Suffice it to say that it’s 7.5 feet (2.286 meters) tall, dates to around 9400 BC18, and is depicted naked with haunting eyes, curiously etched ribs and a prominent phallus beside which rest the figure’s two hands with fingers extended.

Although we hadn’t been able to access the narrative panel we’d gone to Sayburç hoping to document, there was still the excellent public domain photograph of the complete scene that had appeared in Dr Özdoğan’s paper.19 I pulled it up on my cellphone and confirmed my recollection that amongst the figures depicted in the scene was one very similar to the Karahan Tepe giant, similarly seated on a bench and with a similarly prominent phallus. The Sayburç figure is carved in relief, and holds its penis in its right hand, the Karahan Tepe figure is fully three-dimensional and cradles its penis with both its hands, but the essential imagery is the same.

The Gilgamesh scenes at Sayburç

That evening in our hotel room in Sanliurfa, I turned my attention again to the Epic of Gilgamesh and its connection to the trip that Santha and I had just completed in Iraq visiting the ruins of ancient cities associated with the Sumerian Deluge tradition.20 Notable amongst these for the starring role it plays in the epic was Uruk where archaeologists generally suppose that Gilgamesh had been a historical king who had ruled somewhere between 2,800 BC and 2,500 BC.21 There’s also consensus that the Epic itself was composed around 2,000 BC,22 since that is the age of the oldest-surviving written fragments so far found. The possibility being considered here, however – namely that the epic existed and was passed down as an oral tradition for hundreds and perhaps even thousands of years before it was first committed to writing – cannot be ruled out.

If so it might have undergone many local modifications as time went by and the names of principal characters might have changed. For example, the “Master of Animals” figure who the Sumerians called Gilgamesh would certainly have gone by a different name in the 10th millennium BC. Likewise in the 5th millennium BC, the early days of the written record in Sumer, the ancient glamor of the “Master of Animals” might even have been deliberately entangled by sycophantic court scribes with the name of a particular historical king of Uruk, adding to the magnetism of this ancient and storied place:

“Come,” said Shamhat, “let us go to Uruk, I will lead you to Gilgamesh the mighty King. You will see the great city with its massive wall, you will see the young men dressed in their splendour, in the finest linen and embroidered wool, brilliantly coloured, with fringed shawls and wide belts. Every day is a festival in Uruk, with people singing and dancing in the streets, musicians playing their lyres and drums, the lovely priestesses standing before the temple of Ishtar, chatting and laughing, flushed with sexual joy, and ready to serve men’s pleasure, in honour of the goddess, so that even old men are aroused from their beds.”23

The extract is from the Epic of Gilgamesh. And the person being led to Uruk by the temple prostitute Shamhat is Enkidu, the archetypal wild man, created by the Gods to become a match, a soul brother and a dear companion to the unruly King Gilgamesh. The two at first fight – read the Epic itself if you want to know why – but in due course become firm friends. They then set off on various expeditions and perform heroic deeds of which the most heralded are the killing of the forest monster Humbaba, the killing of lions and the killing of the Bull of Heaven. Consider this passage for example:

Gilgamesh arose.. He lifted the axe, he drew the dagger from his belt, he fell on them like an arrow, he struck the lions, he killed and scattered them.”24

Or this one:

Anu…called for the Bull of Heaven and handed its nose rope to the princess Ishtar. Ishtar led the Bull down to the earth, it entered and bellowed, the whole land shook, the streams and marshes dried up, the Euphrates’ water level dropped by ten feet. When the Bull snorted, the earth cracked open and a hundred warriors fell in and died. It snorted again, the earth cracked open and two hundred warriors fell in and died. When it snorted a third time, the earth cracked open and Enkidu fell in, up to his waist, he jumped out and grabbed the Bull’s horns, it spat its slobber into his face, it lifted its tail and spewed dung all over him. Gilgamesh rushed in and shouted, “Dear friend, keep fighting, together we are sure to win.” Enkidu circled behind the Bull, seized it by the tail and set his foot on its haunch, then Gilgamesh skilfully, like a butcher, strode up and thrust his knife between its shoulders and the base of its horns. After they had killed the Bull of Heaven… they both … sat down like brothers, side by side.25

Or this:

Gilgamesh is my name

“I am the king of great-walled Uruk.

I am the man who killed the Bull of Heaven,

Who destroyed Humbaba in the Cedar Forest,

Who killed lions in the mountain passes…26

I have killed bear, lion, hyena, leopard, tiger, deer, antelope, ibex, I have eaten their meat and have wrapped their rough skins around me.27

Absent a figure that could play the part of Humbaba,28 the other principal antagonists faced in the epic by Enkidu and Gilgamesh – big cats and a big bull – are unmissable in the imagery of the Sayburç reliefs. So, too, is the obvious “mastery of animals” theme of the nonchalant onanist and, in general, the “penis focus” of the Karahan Tepe statue and the Sayburç reliefs – with the male organ either held lovingly in hand or admiringly cradled by both hands.

Photo B. Kösker (CCBY4.0)

Photo B. Kösker (CCBY4.0)

Is it an accident that echoes of this penis veneration, and its ultimate futility, are also found in the epic? After Enkidu’s death, for example, his ghost returns briefly from the Underworld to deliver a sombre reminder to Gilgamesh of the inevitable fate of all mortals:

“My friend, the penis that you touched so your heart rejoiced, grubs devour it … like an old garment.29

Not everything fits. In the epic, the killing of the Bull of Heaven, for example, is accomplished by Gilgamesh and Enkidu working together. The relevant relief, on the other hand, shows only a single figure confronting the bull (although that figure admittedly, might be described, to paraphrase the epic, as Enkidu falling up to his waist into a crack in the earth then leaping out to grab the bull’s horns).

Then there is the issue of the object that the falling figure holds in its hand.

Photo B. Kösker (CCBY4.0)

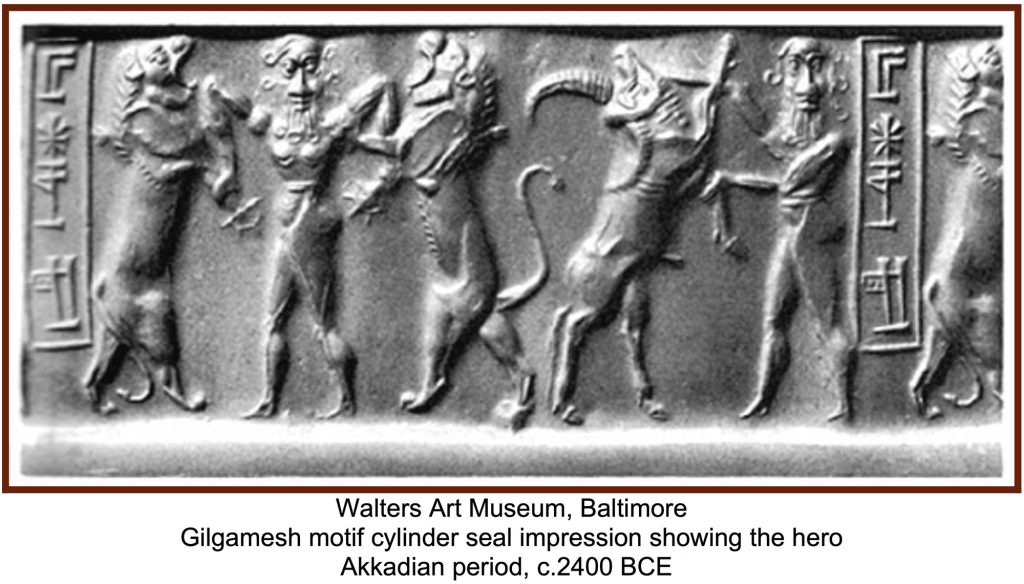

There is no concensus. Some think it is a weapon, but the view of Dr Özdoğan that it is a snake has received support. Whatever it is, a similar object, wide at the “head” end and narrow at the “tail” end, also appears in later Mesopotamian depictions of the Master of Animals:30

Photo Jastrow (Public Domain)

In conclusion, and to be absolutely clear, what I’m suggesting is that Gilgamesh might not have been invented out of the whole cloth by the Sumerians when they first set it down in writing less than 5,000 years ago, as archaeologists have hitherto proposed. My thought is it might already have been in circulation in oral form, in plays and songs and recitations, for millennia before the story made the jump into cuneiform. I propose the Sayburç panel, with its phallic symbolism and its two scenes depicting mastery of animals – the confrontation with the “Bull of Heaven” and the confrontation with lions/leopards – as prima facie evidence for this case. And in conclusion, from Sumer’s Akkadian period around 2400 BC, and now housed in the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, I leave you with this:31

Interestingly, although the man between two felines is on the left in the Akkadian example, and the man confronting the bull is on the right, and although there is a 6,000-year gap between the two images, the complete scene accords strikingly with the “story” told by the Sayburç reliefs.

Photo B. Kösker (CCBY4.0)

I suggest this is not a coincidence.

I suggest it’s a legacy.

References

1 Eylem Özdoğan, “The Sayburç reliefs: a narrative scene from the Neolithic”, Antiquity 2022, Vol. 96 (390), p. 1599

2 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Urn_cambridge.org_id_binary_20221201181421541-0856_S0003598X22001259_S0003598X22001259_fig4.png

3 https://www.facebook.com/Author.GrahamHancock/posts/pfbid02Fw4S7vGpaLCSSx7GjoNDKKofNGRrq6eQ1S5CC4hRh5b2jLvMaqAzPHpGPL9KPFCzl

4 Gilgamesh: A new English version by Stephen Mitchell, Free Press, a Division of Simon & Schuster Inc., New York, 2004

5 https://www.science.org/content/article/prehistoric-carvings-depict-showdowns-between-humans-and-beasts

6 Jens Notroff, Weapons of choice: A Pre-Pottery Neolithic hunting scene (?) from Sayburç, southeastern Turkey (and some thoughts on prehistoric hunting equipment), Medium, 14 December 2022: https://jens2go.medium.com/weapons-of-choice-a-pe-pottery-neolithic-hunting-scene-814cd3c878ae

8 Eylem Özdoğan, “The Sayburç reliefs: a narrative scene from the Neolithic”, op.cit., p. 1604

10 Professor Patrick D. Nunn writing in Sapiens Anthropology Magazine, 18 October 2018: https://www.sapiens.org/language/oral-tradition/. See also: https://www.usc.edu.au/about/unisc-news/news-archiv,e/2023/july/evidence-the-oral-stories-of-australia-s-first-nations-might-be-10-000-years-old. And see Patrick D. Nunn, The Edge of Memory: Ancient Stories, Oral Tradition and the Post-Glacial World, Bloomsbury Sigma, London, 2018.

11 https://grahamhancock.com/hancockg23/. Scroll down to “Closing thoughts” near the end of this blog entry.

12 Eylem Özdoğan, “The Sayburç reliefs: a narrative scene from the Neolithic”, op.cit., p.13

13 Ibid.

14 Discussed at length in my blog: https://grahamhancock.com/hancockg23/

15 As described in Graham Hancock, Magicians of the Gods, 2015.

16 As described in Graham Hancock, Magicians of the Gods, 2015, Chapter 14.

17 For example see https://www.yahoo.com/lifestyle/archaeologists-discover-11-000-old-205242808.html and https://news.artnet.com/art-world/ancient-statue-man-holding-penis-2381399 and https://www.serendipityturkey.com/karahan-tepe-male-statue/ and https://basin.ktb.gov.tr/TR-350158/tarihin-sifir-noktasinda-ilk-boyali-heykel-bulundu.html and https://www.livescience.com/archaeology/11000-year-old-statue-of-giant-man-clutching-penis-unearthed-in-turkey and https://archaeology.org/news/2023/10/23/231024-turkey-sculpture-deceased/

19 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Urn_cambridge.org_id_binary_20221201181421541-0856_S0003598X22001259_S0003598X22001259_fig4.png

20 https://www.facebook.com/Author.GrahamHancock/posts/pfbid02Fw4S7vGpaLCSSx7GjoNDKKofNGRrq6eQ1S5CC4hRh5b2jLvMaqAzPHpGPL9KPFCzl

21 Stephanie Davie, Myths from Mesopotamia, Oxford University Press 1990, p.40.

23 Gilgamesh: A new English version by Stephen Mitchell Mitchell, pp. 17-18, Kindle Edition.

24 Ibid, p. 193.

25 Ibid, pp 102-103

26 Ibid, pp 194-195

27 Gilgamesh: A new English version by Stephen Mitchell Mitchell, p. 126, Kindle Edition.

28 And one might yet appear since much of the area beneath which the Sayburç narrative panel was found remains unexcavated

29 Ibid, pp 154-155

Overly insightful and an interesting take. I’m very new to the discussion on all this and still doing my own due diligence so thank you for providing this.