“Gobekli Tepe changes everything.” – Ian Hodder, Stanford University.1

In Episode 5 of my documentary series Ancient Apocalypse, released on Netflix in November 2022, I speak of GobekIi Tepe in southeastern Turkey, which is reliably dated to around 11,600 years ago. I introduce it as the oldest megalithic archaeological site that has yet been discovered anywhere in the world:

“It’s an enormous site, you can’t just wake up one morning with no prior skills, no prior knowledge, no background in working with stone and create something like Gobekli Tepe. There has to be a long history behind it and that history is completely missing…

To me it very strongly speaks of a lost civilisation, transferring their technology, their skills, their knowledge to hunter gatherers…”

I’ve spent more than 30 years on a controversial quest for a lost civilization of the Ice Age. You could say it’s my obsession. Perhaps it was because I was so caught up in the search on my first visits to Gobekli Tepe in 2013 and 2014, and so impressed by the genius of its design and its monolithic T-shaped pillars with their intricate carvings, that I didn’t fully appreciate how complicated its inheritance of technology transfer had been. Nor did I grasp how much of the history of that transfer, even though it went unrecognized as such, had bit by bit begun to be revealed by archeologists. In consequence, I overlooked excellent, high-quality data, which, if I had deployed it at the time, would have strengthened my own thesis greatly.

The transfer didn’t begin with Gobekli Tepe – which is itself 7,000 years older than Stonehenge. It didn’t even begin in the Neolithic. It began millennia earlier with Late Epipalaeolithic cultures, one of which has, since the 1920s, been referred to as Natufian. Of course, we don’t know what it was called by its own people, or even if it consisted of a single culture or multiple different cultures sharing similar lifeways. Moreover, new finds are constantly challenging our understanding of it. Thus, the Natufian was initially thought to be an exclusively nomadic or semi-nomadic hunter-forager2 culture typical of the period, but excavations at Ein Mallaha (also known as Eynan) in northern Israel, some 600 miles south of Gobekli Tepe, uncovered substantial architectural features:

Semi-subterranean curvilinear structures… made of undressed limestone characterized the site throughout its history. Their construction usually consisted of cutting into the slope and building retaining walls in order to support the surrounding sloping ground. The superstructure (roof) of these shelters [a combination of associated structures and floors] was presumed to have been made of organic material.3

As a result of these discoveries at Ain Mallaha, report archaeologists Gill Haklay and Avi Gopher of the University of Tel Aviv, “the innovation of stone construction” began to be recognised as:

“part and parcel of the Natufian repertoire. Prior to the Natufian, stone architecture, which is generally associated with sedentism, was rare and it later became a hallmark of the Neolithic period.”4

In 2015, deploying architectural formal analysis to study the relationships between different construction elements, Haklay and Gopher undertook a close investigation of one of Ein Mallaha’s largest buildings, “Shelter 51”. Dated to the Early Natufian around 14,300 years ago,5 this structure has a number of peculiar and eye-catching characteristics, in addition to its rarity as an early example of stone architecture, that seem – to my eyes at any rate – to be out of place in time. Amongst these characteristics, the most notable, distinguishing Shelter 51 from earlier structures that have been claimed as predecessors dating as far back as the early Epipalaeolithic (around 20,000 years ago),6 is clear evidence of the use of geometry and a pre-prepared ground plan, revealing what Haklay and Gopher describe as:

“a whole new level of architectural design… Architectural with a capital A…7

“Here, the designer addressed and integrated the different aspects of architectural planning, including spatial organization, structural system and spatial form, under a common geometric concept. This resulted in a standardization of the structural and spatial elements. Unlike the early Epipaleolithic brushwood huts, Shelter 51 was envisioned by its designer in its totality and in a different level of detail. Thanks to the use of geometric concepts, a shape of a floor plan could have been defined and specified prior to its marking on the ground, and an architectural design could have been shared with others and carried out with accuracy. As worded by Marx relating to human productivity: ‘A spider conducts operations that resemble those of a weaver, and a bee puts to shame many an architect in the construction of her cells. But what distinguishes the worst architect from the best of bees is this, that the architect raises his structure in imagination before he erects it in reality”.8

Future discoveries may force further revision of the picture, but it is beginning to look very much as though the earliest surviving evidence for the deliberate use of geometry and an architectural plan, so typical of Gobekli Tepe 11,600 years ago, comes down to us from the Natufian culture somewhere around 14,300 years ago. As Haklay and Gopher conclude:

“The Natufian level of architectural planning, an innovation made possible by the introduction of a geometric tradition, represents a turning point in human/environment relations, as the role of geometry in architectural design and its manifestation in the spatial form of the built environment were destined to become predominant…”9

Nor is Structure 51 the only example:

“The Natufians were also familiar with the notion of a ‘perfect’ and precise circle. It is evident, for example, from the 62cm high mortar and stone discs retrieved from the site of Eynan. These artifacts possess a strikingly high degree of symmetry, and reflect the intention and ability of producing objects of such properties.”10

Narrowing the search for a lost civilization

Hypothetically, civilizations of the past could have become “lost” to us today – i.e. not represented by archaeological evidence that is plentiful and compelling enough to persuade us of their existence – for multiple reasons. Furthermore, it makes sense that the probability of a lost civilization is higher during “prehistory” (periods and cultures from which no written documents have survived) than it is during “history” (periods and cultures from which we do have written documents). I say “periods” rather than “period” because epochs without written documents vary widely from region to region. Thus, the earliest written language of the Middle East – Sumerian – dates back more than 5,000 years, whereas the earliest written language of the Americas, the hieroglyphic script of the Olmec civilization of Mexico, is thought to be about 3,000 years old.

Modern scholarship recognizes no written language anywhere in the world during the series of Ice Ages that gripped the planet between roughly 2.6 million years ago and 11,600 years ago. Although the very idea appears to be abhorrent to most archaeologists, the possibility that a lost civilization hides somewhere in this vast wilderness of time cannot be completely ruled out. On the contrary, I think it’s something worth searching for. Since we are anatomically modern humans, however, and since the earliest evidence of anatomically modern humans so far found dates back only 315,000 years (Jebel Irhoud, Morocco11), it makes sense to narrow our initial search to that timeframe – let’s say the last 400,000 years.

In every one of these years, until around 11,600 years ago, Ice Age conditions prevailed across much of the Earth, and the cyclical shrinkage and expansion of the continental ice sheets – of glacial and interglacial phases – was accompanied by huge climate shifts and geological changes. Indeed, though presently enjoying the benefits of a sustained warm period, many scientists argue that we are still in an Ice Age today and that further rapid global warming and rapid global cooling can be expected in the millennia to come.

Estimates of the precise beginning and end of climate episodes become less precise the further back we look into the past, but it’s safe to say that by 400,000 years ago, the Earth had already been basking in an interglacial phase for some millennia. The climate of this phase appears to have been warm, well-watered and, in general, congenial to the development of human culture. No form of civilization recognized by archaeologists emerged, however, and around 300,000 years ago, for unknown reasons, warm switched to cold and much of the planet fell into the iron grip of an icy winter in which it was doomed to stay locked for the next 170,000 years. When the freeze did end, around 127,000 years ago, a rapid warming phase followed. Known technically as the “Eemian”, this golden age lasted for more than 20,000 years, during which conditions were significantly better than those that we enjoy today and thus optimal for the rapid development of human culture.

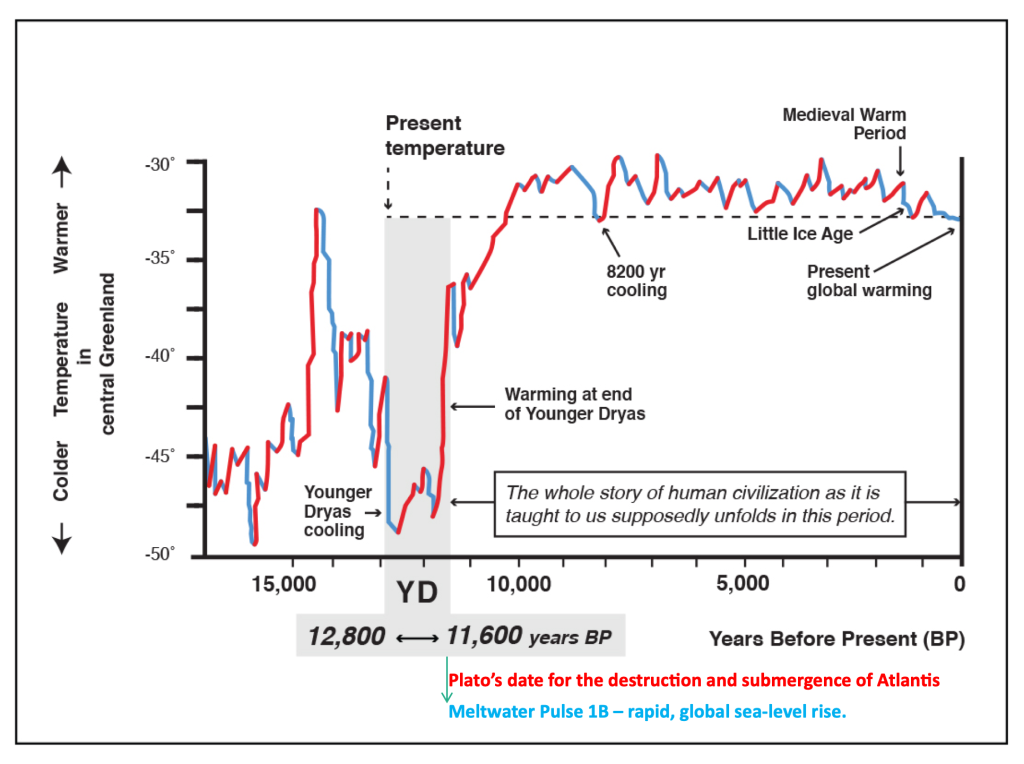

Around 106,000 years ago, as suddenly and as mysteriously as it had begun, the Eemian came to an end, and a long Ice Age set in which, like all episodes of glaciation before it, was characterized by significant climate fluctuations. Thus, from 80,000 years ago down to around 12,800 years ago, climate evidence in ice-cores recovered from Greenland glaciers shows that global temperatures were always colder than they are today but shifted repeatedly between bitterly cold “stadial” conditions and much milder “interstadial” periods. Now commonly referred to as Dansgaard-Oeschger cycles (or “D-O cycles”), twenty-five of these distinct warming-cooling oscillations have been identified in the past 80,000 years. “One of the most surprising findings,” write oceanographers Matthew Schmidt and Jennifer Hertzberg of Texas A&M University, “is that the shifts from cold stadials to the warm interstadial intervals occurred in a matter of decades, with air temperatures over Greenland rapidly warming 8 to 15°C… The cooling occurred much more gradually, giving these events a saw-tooth shape in climate records from most of the Northern Hemisphere.”12

Climate variability over the past 80,000 years GISP2 Ice Core Oxygen Isotope Data, P. M. Grootes, M. Stuiver. 1997 [Direct link]

Within the already harsh and limiting conditions of an Ice Age that finally reached its greatest extent some 21,000 years ago – the “Last Glacial Maximum” – such a rapid succession of warming and cooling events would have placed significant obstacles in the path of any civilization. It is thus noteworthy, since the development of settled agriculture was for a long while regarded as a fundamental hallmark of “civilization”, that the archaeological record contains evidence of what might be termed as “proto-agriculture” between roughly 23,000 years ago and 19,000 years ago13 – a window that brackets the Last Glacial Maximum. This evidence comes from a site known as Ohalo II in the Jordan Valley near the modern Sea of Galilee in northern Israel and demonstrates that the inhabitants were making use of wild grains and cultivating certain plants:

“To date, 142 botanical taxa have been registered, and more than 19,000 grass seeds, including wild wheat and barley, have been identified. Heavy ground stone equipment is found at the site, and traces of starch were found on the working surface of one stone that was examined… The stored seeds imply that people were certainly there from early summer for several months. The combined floral and faunal data show that people were using the site all year round, even if they may not have been in residence year in year out.”14

The remains of several brushwood huts were excavated, but otherwise, archaeologists found no evidence that any breakthrough to permanent settlement, plant domestication and full-scale agriculture was ever made at Ohalo II – or at any other site so far discovered anywhere in the world in the millennia of unstable and unpredictable climate immediately following the Last Glacial Maximum. Around 14,700 years ago, however, a warm and moist epoch known as the Bølling–Allerød interstadial began with conditions that were once again optimal for the development of civilization. Whereas most previous climate shifts had seen freezing temperatures restored within a few centuries, this interstadial proved to be a mini golden age that lasted for nearly 2,000 years. Yet, when it came to an end around 12,800 years ago, it did so with breathtaking and unprecedented rapidity. Unlike most prior cooling episodes, which had set in slowly, this one came on virtually overnight, plunging the world back into a freeze as cold and as hostile to civilization as the Last Glacial Maximum.

This sudden return to peak Ice Age conditions, so different from the previous Dansgaard-Oeschger fluctuations, is referred to technically as “The Younger Dryas”. It lasted for around 1,200 years, from roughly 12,800 years ago, when the cold began, to roughly 11,600 years ago, when an episode of extreme global warming brought it to an end. Archaeologists note that the Younger Dryas, unlike previous climate fluctuations, coincides with a great transition in the human story – a transition once referred to as the “Neolithic Revolution” – that saw the shift from the Upper Palaeolithic to the Neolithic, from hunting and gathering to farming, and from lifeways that had not changed significantly for hundreds of thousands of years to the bewildering complexity and constant innovation of emergent civilizations.

Why do these great shifts in human behavior cluster around the Younger Dryas, a time of crisis and radical climate change, rather – for example – than around the balmy and nurturing episodes of the Eemian and the Bølling–Allerød interstadials? And if radical climate change was itself a factor in the emergence of civilization, why have archaeologists been unable to correlate any of the many earlier episodes of extremely unstable climate with the origins of civilization?

Or is it possible that the most significant shift of all, the shift to true civilization, could have occurred much earlier, in some as yet unsuspected part of the world, and gone largely unnoticed and unremarked in the archaeological record?

Paradox? Or artefact?

Let me put my cards on the table. Having spent the past 30 years searching for a lost civilization of the Ice Age, I suspect that the Younger Dryas was not the first but the second watershed moment in the human story. I suggest, but do not claim to prove, that the first occurred much earlier, during the Eemian, between 127,000 years ago and 106,000 years ago – a period of 21,000 years in which global conditions were significantly more conducive to the growth and development of a civilization than any, including those of today, that humanity has subsequently enjoyed:

It is estimated that the Eemian temperatures were 1–2° higher than the current ones. In England, the fossil studies show tropical fauna such as hippopotami… In addition, the study of corals and foraminifera shows that the seas were 2–3° degrees warmer than the current temperature… During this period, the Earth’s orbit around the sun was more eccentric and its perihelion coincided with summer in the Northern Hemisphere (today it corresponds to the aphelion). The inclination of the earth was also greater than the current 23°27′. This led to a seasonality and the heat was greater, with colder winters, than at present… In Africa, the equatorial forest occupied a greater extension than currently and the Sahara was constituted by a savannah with transition to steppe vegetation. In addition, it was inhabited by lakes…”15

Hippotami in England! Lakes in the Sahara! The climate of the Eemian created a kind of hot and steamy “Garden-of-Eden” world in which humanity was suddenly presented with opportunities that had been shut off during the previous 170,000 years of the Saale Glacial – the name given by modern geologists to what must have seemed, to the people of the time, to be an endless icy winter.

Those people were human beings – in every respect just like us, with the same abilities, the same creative cunning, and the same potential for innovation that we pride ourselves on. They were just as capable as we are of adapting to sudden changes and taking advantage of sudden opportunities. The absence of evidence that any human group anywhere ever seized the opportunities of the Eemian to thrust itself forward onto the stage of civilization is, therefore, either a paradox of the archaeological record or an artefact of the fragmentary and incomplete nature of the record itself.

If not in the Eemian, then when are the earliest unequivocal signs of civilization recognized?

Here, questions of what a civilization is, how it is to be defined, what characteristics it must possess, etc, etc, are fundamental, and I will address them in due course. Briefly, however, my understanding of the evolving archaeological consensus is that the word “civilization” has become unmoored from its old etymological connection to the word city and is in general much more broadly and loosely defined today than it once was.

A second problem is that accidents of archaeological discovery inevitably prejudice the record by causing exploration and digs to be focused on certain regions while drawing funding and expertise away from others. A current example is the huge amount of archaeological attention paid to south-eastern Anatolia in Turkey since the discovery there of Gobekli Tepe. As a result of this surge of interest in a hitherto neglected region, many more megalithic sites have been investigated within a radius of several hundred square kilometers, and the lineaments of a truly lost civilization are beginning to emerge from the Anatolian dust.

The question inevitably arises – how many other regions of the world, hitherto underserved by archaeology, conceal equally stunning sites?

The answer? We don’t know…

In Anatolia, however, and in its hinterland extending as far south as Cyprus and the Jordan Valley, the recent decades of intense archaeological scrutiny do at least allow us to know that something—something big, something vibrant— had begun to take shape there by about 14,300 years ago…

The predictable outcome of a perfectly normal process?

Located in the Hula Valley of northern Israel, the Natufian site of Ain Mallaha was continuously occupied from around 15,000 years ago, a few centuries before the warm conditions of the Bølling–Allerød interstadial set in, until the height of the Younger Dryas cold event around 12,000 years ago.16

| Periods | Approximate dates in absolute years ago | Cultural labels in the Levant |

|---|---|---|

| Upper Palaeolithic | 45 000–25 000 BC | |

| Early Epipalaeolithic | 23 000–15 000 BC | Kerbaran |

| Middle Epipalaeolithic | 15 000–13 000 BC | Geometric Kebaran |

| Late Epipalaeolithic | 13 000–10 200 BC | Natufian |

| Early aceramic Neolithic | 10 200–8800 BC | PPNA (= Pre-Pottery Neolithic A) |

| Late aceramic Neolithic | 8800–6900 BC | Early, Middle, Late & Final PPNB |

In terms of the archaeological timeline given in the table above, we can say that Ain Mallaha begins its long life in the Late Epipalaeolithic and ends it in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic – the PPNA. Though sites from this epoch with such longevity are rare, others are known. Notable examples include Cemka Hoyuk, Boncuklu Tarla, Kortik Tepe17 and Abu Hureyra. In the latter, archaeological investigations revealed a very long-term occupation by people:

“who initially practised hunting-and-gathering in the late Epipaleolithic (~13,400 cal BP) before transitioning to full-scale farming by the early Neolithic.”18

Even in its earliest, Epipalaeolithic phase, Abu Hureyra boasted multiple large circular semi-subterranean structures, interpreted as domestic dwellings, organised into three distinct complexes.19

Another example is Tell Qaramel in northern Syria, excavated by the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology at the University of Warsaw. Covering some 3.5 hectares and straddling the Epipalaeolithic and the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, the site is distinguished by five circular stone towers carbon-dated to the period from the middle of the 11th millennium BC to about 9650 BC, which makes them, as the excavators point out, “the oldest structures of this type in the world.”20 Moreover, these extraordinary towers were part of an extraordinary and obviously permanent settlement:

“In the trenches located beside the towers about 90 domestic buildings and outhouses were discovered, as well as three temples/assembly places, numerous hearths and pits. Thirty-five human burials and several animal ones were found under the floors of some houses and in oval or circular pits dug between buildings. The deceased were laid in an embryonic position and a few of the graves were furnished with stone or bone beads and plaques.

Also discovered in the settlement was a rich collection of objects of everyday use made of flint and bone but predominantly of stone like chlorite and limestone. Many of them were richly decorated with geometrical, animal and anthropomorphic motifs.

In the case of Qaramel, the most astounding thing is the fact that such highly-developed culture took roots in a community of hunter-gatherers (during the work conducted thus far no traces of the domestication of animals or the cultivation of grains were found).”21

In stark contrast to the kind of overnight “Revolution” in the Epipalaeolithic-Neolithic transition favoured by their 20th century predecessors, archaeologists these days see a gradual process at work leading towards ever larger permanent settlements coupled with the step-by-step development of architecture and agriculture. It is therefore argued that Gobekli Tepe is not, as I had claimed, the result of some kind of “transfer of technology” from the survivors of a lost civilization around 11,600 years ago but simply the predictable outcome of a perfectly normal process of social and technical evolution that began much earlier with the Natufian.

This feels like a reasonable argument. The Natufians were early adopters of stone architecture. Their curvilinear semi-subterranean dwellings seem to prefigure the curvilinear semi-subterranean structures of Gobekli Tepe, and Shelter 51 at Ain Mallaha, dated to 14,300 years ago, features the use of geometry and an architectural plan that would turn up again in Gobekli Tepe 11,600 years ago.

Indeed, Hacklay and Gopher address this very point in a paper entitled “Geometry and Architectural Planning at Gobekli Tepe” published in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal in 2020. They begin by reminding us that:

In the archaeological record, architectural planning that includes specifications of architectural spatial forms prior to construction becomes archaeologically visible with the appearance of stone-built shelters in the late Epipaleolithic period (Natufian sites) in the Levant…. Both the planning and the execution of the plan with accuracy were made possible by conceptualizing basic geometric ideas and methods such as circle, centre and compass arm.22

In the case of Gobekli Tepe, Hacklay and Gopher’s research has revealed a hidden geometric pattern in which the three oldest enclosures, B, C and D, are linked by a plan based on an equilateral triangle:

“Each enclosure subsequently went through a long construction history with multiple modifications but at least in an initial phase they started as a single project…The implication is that a single project at Göbekli Tepe was three times larger than previously thought and required three times as much manpower – a level that is unprecedented in hunter-gatherer societies.”23

While geometry remained a constant feature, the notion that enclosures B, C and D began as a single project also has implications for the evolution of architectural knowledge in the region from its Early Natufian beginnings 14,300 years ago to the splendours of Gobekli Tepe 11,600 years ago:

The use of geometric construction in architectural planning enabled the planner to conceptualize a proportional abstraction of a floor plan of a rather complex design, and to reproduce it at any size. While the relatively simple architectural plans conceptualized in the preceding late Epipaleolithic Natufian may have been mental ‘cognitive plans’, during the PPNA, the dramatic increase in complexity of the architectural design must have required the formulation of a schematic (diagrammatic) small-scale floor plan which consisted of a pattern, geometrically constructed and regulated by a length module…. The concept of a floor plan as an external planning device is probably the biggest step forward in Neolithic architectural planning.

Despite the evidence for geometric thinking and ‘cognitive plans’ in the Natufian, Hacklay and Gopher are therefore clearly of the view that the big step forward to diagrammatic plans was not taken until the Neolithic – in other words, what they’re envisaging is, by any other name, a kind of “Neolithic Revolution”.

Though the idea has become unfashionable amongst archaeologists, I suggest that the data from Anatolia and the Levant quite strongly support a revolution of some sort, although not a specifically “Neolithic” revolution. Its traces begin to appear in the archaeological record only after the onset of the Younger Dryas around 12,800 years ago, and thus several centuries before the beginning of the pre-pottery Neolithic, which archaeologists put at around 12,200 years ago.

Those five hulking towers at Tell Qaramel are an example. As we’ve seen, carbon-dating puts the construction of the earliest of them at the middle of the 11th millennium BC – i.e. around 10,500 BC or 12,500 years ago – and the latest at 9,650 BC, a date that coincides more or less exactly with the end of the Younger Dryas and the construction of Gobekli Tepe’s megalithic enclosure D.

Also of relevance is Boncuklu Tarla in Mardin Province, Eastern Turkey, close to the Tigris River. Here, building work began during the Late Epipalaeolithic around 12,400 years ago, and continued through both the PPNA and PPNB phases of the Neolithic.24 Particularly striking structures, Building 011, named the “Buttress Building” by lead excavator Ergul Kodas, and EA Structure 1, named the “Pillar Building”, straddle the Late Epipalaeolithic and PPNA boundary some 12,200 years ago and feature the eponymous buttresses and pillars.25

“The form and internal organization of EA Structure 1,” notes Kodas, “differs from other communal buildings at Boncuklu Tarla… The limestone slab pillars are similar to the ones known from… Göbekli Tepe…”26

Kodas adds that, in his view, the characteristics of EA Structure 1 are “related to faith… We can say that it is a temple dating back to twelve thousand years.”27

If it is indeed twelve thousand years old, then this “temple” was built during the Younger Dryas cold period. So, too, was the circular “Buttress Building”.28 As Kodas concludes:

“The presence of architectural remains dated to the Younger Dryas at Boncuklu Tarla provides important information regarding the transition to a sedentary life model… Uninterrupted occupation of Boncuklu Tarla indicates continuity between the Younger Dryas and the Early Holocene Period. Furthermore, at Boncuklu Tarla, the presence of public buildings together with residential buildings and of…stone masonry stele… is extremely important in showing that the construction of public structures with pillar, which will be the dominant architectural system in the PPNA and PPNB Periods of Northern Mesopotamia, actually started in the Proto-Neolithic Period.”29

That an evolutionary framework has been found to explain the “dominant architectural system” of Gobekli Tepe and later PPNA and PPNB sites is obviously a matter of satisfaction to archaeologists. Nonetheless, it is clear that Kodas himself is puzzled by some of the architectural features that he and his team have excavated at Boncuklu Tarla. He draws special attention to the fact that communal structures such as the “Pillar” and “Buttress” buildings were semi-subterranean and appear to have been solidly roofed with integrated stone features:

“when the structure was built, a large hole was dug and the building was built into the hole… The inside of a large stone was carved and a gap was made. Most likely, it provided lighting and entrance and exit from the roof – because the building doesn’t have any doors… It’s absolutely clear that the building was entered through the roof. It’s a bit like they live underground…”30

That the inhabitants of Boncuklu Tarla built structures that sound very much like underground bomb shelters capable of accommodating large numbers of people makes sense once it is set in the context of the spectacular natural disaster that afflicted this region during the Younger Dryas. The exact nature of that disaster is a matter to which we shall return. Meanwhile, let us note in passing here that, when excavated, the Younger Dryas stratum at Boncuklu Tarla proved to consist of “a dark brown burnt fill with thick ash.”31 Moreover, “the earliest soil of the Holocene Period” turned out to be “a sterile, brick-red layer… No archaeological finds have been discovered in this sterile layer.” Despite its long history of habitation, therefore, it seems that Boncuklu Tarla was briefly abandoned or partially abandoned at the Younger Dryas/Holocene transition some 11,600 years ago…

That was around the same time that the oldest enclosure of Gobekli Tepe, Enclosure D, was built. It, too, was a semi-subterranean structure, most likely accessed through its roof, and it too was notable for its pillars – one of which, as we shall see, bears complex relief carvings that have been claimed to refer to the Younger Dryas cataclysm.

That there is clear and incontrovertible evidence of cultural continuity between the Natufian and the Neolithic across a wide geographical range – from the Jordan Valley in the south to Anatolia in the north – is not in doubt. My purpose here is not to dispute that continuity; on the contrary, I embrace it. In my view, however, any sense of vindication that archaeologists may feel for their favoured evolutionary (as opposed to diffusionist) explanation for the immense social, economic and technological changes of the Neolithic – changes that truly set humanity on the path to the world we live in today – is unwarranted. Why? Because the evolutionary model fails to take into account the latest scientific data on the Younger Dryas itself, which we now know was much more than just a “cold spell” and amounts, according to some researchers, to a cataclysm not simply on a regional but on a global scale.

While fully recognising that several changes begun in the Natufian bore fruit that ripened in the Neolithic, what I find particularly notable is that the vast engine of transformation that ushered in the modern world did not really get started until after the onset of the Younger Dryas, kept up a fast pace through the rest of the Younger Dryas and continued to have a measurable impact for several centuries thereafter.

This is true whether we speak of settlements like Boncuklu Tarla and Tell Qaramel, associated with Late Epipalaeolithic cultures similar to the Natufian, or whether we speak of settlements like Abu Hureyra, Ain Mallaha and Jericho that had definite Natufian beginnings, or whether we speak of Gobekli Tepe and multiple other spectacular sites across Southwest Asia that did not “switch on” until the Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPNA) which spans the period from roughly 12,200 years ago until 10,800 years ago.32

Since science sets the end of the Younger Dryas at around 11,600 years ago, this means that its climate conditions overlapped for some 600 years with the beginning of the PPNA. And, of course, the Younger Dryas itself set in much earlier – at around 12,800 years ago. It is the “coincidence” of the suddenly increased pace of social, economic and technological change between 12,800 years ago and 11,600 years ago – and in the following centuries – that really intrigues me.

Change like the construction of Tell Qaramel’s five towers, the earliest of which is dated to around 12,500 years ago, just 300 years after the onset of the Younger Dryas. Or, at the other end of the period, change like the construction of Enclosure D at Gobekli Tepe dated to around 11,600 years ago.

Let’s take a closer look at some of these sites, the true inheritors of what still looks to me – despite the protests of archaeologists – very much like some kind of “revolution”. Nor are all archaeologists on the same page around the highly-charged issue of evolution versus revolution that lies at the heart of this matter. As Gil Hacklay and Avi Gopher wrote in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal in 2020:

Together with sites such as the PPNA Jericho in the southern Levant with its complex construction projects, Göbekli Tepe reflects a ‘foreign country’— a quantic jump of the latest hunters-gatherers in the region, a ‘wild growth’, a disorder of sorts in the hunting-gathering world, way beyond the capacity of a pristine hunter-gatherer society.33

Jericho

The outstanding feature of this late Epipalaeolithic and Neolithic settlement in the Jordan Valley is a massive stone tower, somewhat like the towers of Tell Qaramel but, at almost 30 feet in height, significantly larger in scale. It’s construction, notes archaeologist Rémi Hadad of University College London:

“required the transportation of limestone blocks over at least a kilometre – and in particular, the 30 or so monolithic elements, thick, shaped slabs of about 1m in length and almost as wide, which constitute the steps and lintels of the single staircase that crosses the complex…”34

Archaeologists now allocate the tower to the PPNA period35, although it is not clear whether it was built close to the beginning of that period, around 12,200 years ago or closer to its end around 10,800 years ago.36 Generally, a date of around 11,000 years ago, a few hundred years after the end of the Younger Dryas, is preferred.37

As well as the solidity and advanced characteristics of its construction, including what is perhaps the world’s oldest-known built stone staircase, studies have shown that sophisticated astronomers must have been at work in the design and construction of the Tower of Jericho which is aligned, very precisely, to the summer solstice sunset.

“The tower was built using what can only be described as Neolithic groundbreaking technologies,” write archaeologists Roy Liran and Ran Barkai. “It was very much the super-skyscraper of its day.”38

WF16

WF16 is a large PPNA site at Wadi Feynan in the southern Jordan Valley.39 Excavated between 2008 and 2010, it dates to c. 9800–8200 BC (i.e. 11,800 – 10,200 years ago) with a focus on activity between 9400 and 9100 BC.40

At the northern end of the settlement, Structure O75 (as nominated by the excavators) is noteworthy for being:

“an impressive 20 m × 18 m in size, consisting of a mud plaster floor with multiple surfaces surrounded by a bench over 1 m deep and up to 0.5m high, part of which has a second tier of similar dimensions, with a probable platform at the northwest apex of the structure. These provide an amphitheatre-like form to the structure. The face of the lower bench on the southern side of the monument was decorated with a wave pattern… A series of massive post-holes moulded into the surrounding wall, shallow post-holes in the centre of each gully and stake-holes in the floor suggest wooden posts, possibly supporting a superstructure. The best estimate for the date of its original construction is 11,320–11,240 cal BP… The post-pipes and stake-holes suggest it had been partially or wholly roofed. This would have required a complex construction because its size could not have been spanned by single timbers… The design of O75 makes it difficult to resist the idea that it has been used for performance of some manner—singing, dancing, ceremonial activities.41

Of note is evidence that elaborate costumes for use in the structure were crafted from the feathers of large birds of prey, including eagles, vultures and buzzards.42 In other contexts, such paraphernalia are strongly associated with shamans, and, there is little doubt that shamanism was fundamental to the PPNA spiritual world.

Two other points may also be significant. First, a stone monolith was excavated at the WF16 complex.43 Although small by comparison with the megalithic pillars of Gobekli Tepe, it is positioned in a niche of a stone-walled building.44 Secondly, the “wave pattern” on the bench structure at WF16 bears comparison with a similar pattern on a similar bench at the site of Jerf El Ahmar.45

Jerf el Ahmar

The PPNA site of Jerf El Ahmar in northern Syria was occupied between 9500 BC and 9000 BC46 – i.e. between about 11,500 and 11,000 years ago. The transition from foraging wild plants to mixed domestic farming involving the deliberate cultivation and domestication of useful species was previously thought to have taken place around 10,000 years ago. However, “the discoveries at Jerf El Ahmar”, note excavators George Wilcox and Danielle Stordeur:

“demonstrate that large-scale cereal exploitation and cultivation were practised at least a millennium before this date.”47

Other notable features of the site include the remains of several large “kiva-like” communal stone buildings.48 These were initially circular with internal benches, as in the enclosures at Gobekli Tepe and WF16,49 and subsequently rectangular in form.50 Archaeologists Gil Haklay and Avi Gopher, experts in the architectural analysis and geometry of ancient structures, undertook a detailed study of two of these buildings:

“Communal Structure EA53 is assigned to the latest occupational phase in the site, defined as a PPNA-PPNB transitional phase. It is a circular, embedded in the ground structure, built against the perimeter wall of an older structure. The peripheral stone wall, about 2.40 m high, was built with slots to accommodate wooden posts, and was plastered. At the center of the structure (at the lower elevation), a hexagonal floor is defined by decorated stone panels. Large posts were positioned at the corners and their imprints were preserved in a decorated clay coating.

“Communal Structure EA30 is located on the flat summit of the western hill. It is a curvilinear structure embedded in the ground, surrounded by open space as well as free-standing rectangular structures. The latter are among the oldest rectangular structures recorded thus far not only in the Levant but worldwide. The roof of EA30, probably above ground level, was supported by the perimeter wall and wooden posts embedded within it.

“Two thick radial walls may have been load-bearing walls as well. The interior layout of the structure comprises a central, polygonal shaped floor at the lowest elevation, surrounded by elevated platforms and cell-like enclosures built against the perimeter wall. Stordeur [the original excavator] accurately described the dividing walls as forming a geometric and radiating figure, and she noted that some walls are directed to a point in the perimeter wall that is also the point of intersection between the perimeter wall and the axis of symmetry.”51

Hacklay and Gopher’s analysis found compelling evidence of high-precision design that made use of a deliberately-calculated unit of measure approximately equivalent to 0.54m.52 They were also able to confirm Stordeur’s observation of a “perfect equilateral hexagon”. In their view, its precise geometric regularity indicates that the hexagonal form was measured and, most probably, was laid out on the ground using ropes.53

“We suggest,” they conclude:

“that the appearance of rectangular architecture should be understood against the background of the advances in architectural planning methods, such as the use of floor plans, distance measuring and the geometric construction of polygons. It was, therefore, a top-down process that was initially derived from specialized fields of knowledge and methods, reflected in communal architecture.”54

Kortik Tepe

Dated to the tenth millennium BC,55 and more precisely to 9660-9320 BC56 (and thus roughly contemporaneous with the oldest levels of Gobekli Tepe), Kortike Tepe features curvilinear stone structures and tombs grouped together – “implying”, archaeologists Vecihi Özkaya & Aytaç Coşkun suggest, “a permanently settled centre rather than a temporary camp for hunter-gatherers”.57 Moreover:

“The finds, notably from the tombs buried under the floors of the structures, suggest social differences in a socially advanced community. The differences in the quantity and quality of grave goods – such as stone vessels, thousands of stone beads, stone axes, and other tools – show variants of belief and social status among the earliest permanent community.”58

There is evidence that Kortik Tepe suffered frequent fires – “heavily burned stones”, “river pebbles blackened from fire”, “a thick layer of charcoal”, “a cultural layer with heavy traces of burning”, “organic dark brown earth with charcoal”, “a very ashy layer”.59 It seems, however, that it was never abandoned:

the Epipalaeolithic occupation at Körtik Tepe supports a repeated and possibly continuous commitment to the site from the Younger Dryas to the early Holocene and suggests a permanent living on the site, if not for all, then at least for a substantial part of the community. Despite the pronounced changes in ecology at the transition from the Younger Dryas to the early Holocene, the inhabitants of Körtik Tepe stayed at that location and their settlement flourished during the early Holocene before they abandoned it forever.60

Wadi Hammeh 27

At Pella in Jordan, the site named Wadi Hammeh 27 by archaeologists has been identified as a “Natufian base camp” and dated to around 12,000 years ago.61 Features include large oval limestone dwellings with hearths, postholes, pavements and boulder clusters superimposed upon a layer of human burials. Excavations have recovered 275 basalt artefacts and more than 550 bone artefacts, notably sickles. The site has also yielded “a rich and varied repertoire of rock-art ranging from large rock slabs incorporated into the walls of a dwelling, to small incised limestone plaques.”62

It’s the view of archaeologists Bill Finlayson and Cheryl Makarewicz that “the presence of one very large building at Wadi Hammeh 27 (c. 13m diameter) with standing stones and one decorated stone slab” suggests that this structure “served as much more than the simple shelters of the earlier Epipalaeolithic” and is indicative of “a shift in how people associated with places, their conception of themselves in the landscape, and in their ability to engage collectively in long-term projects.”63

Sayburç

Excavations began in 2021 at Sayburç, 60km east of the Euphrates River, on the southern margin of the eastern Taurus Mountains. Two separate Pre-Pottery Neolithic occupations were revealed: “The first, which comprises communal buildings, is located in the northern part of the village… The second, consisting of residential buildings, is located 70m further south.”64

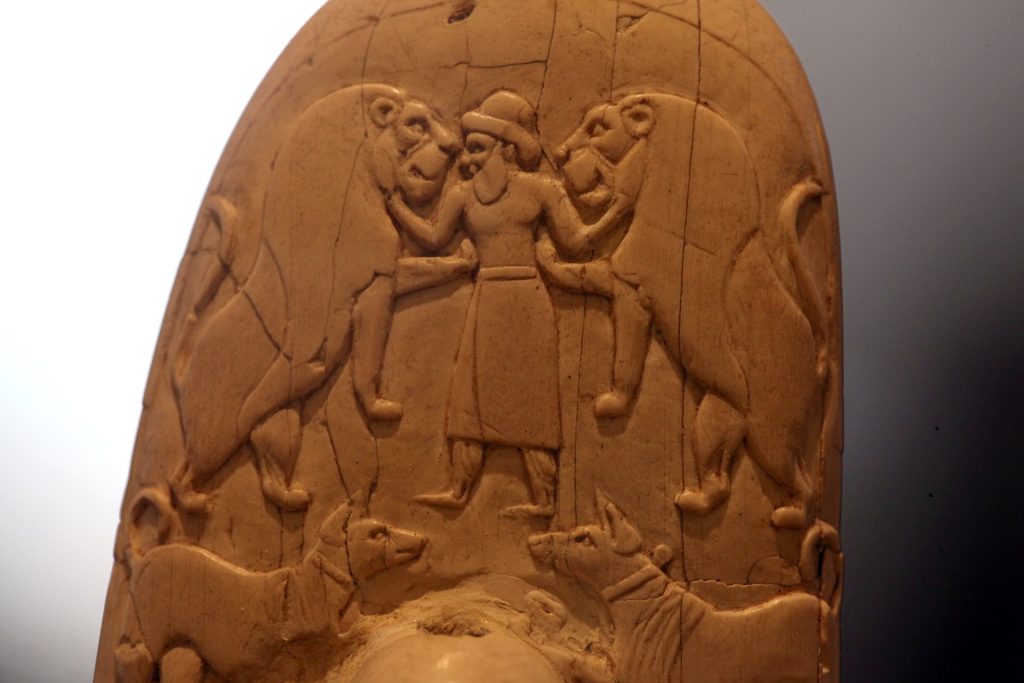

One of the communal buildings was found to contain a panel carved in a mixture of low and high relief, dated to the “ninth millennium BC” and hailed as the world’s ‘earliest-known depiction of a “narrative scene”.65 From the excavators’ report:

The communal building measures 11m in diameter, and was carved into the limestone bedrock, with stone-built walls that rest on a bench, which rises from the floor. The bench measures approximately 0.6–0.8m high and 0.6m wide and displays a number of ∼0.4m-wide cavities extending along the wall, suggesting that it had originally been partitioned by pillars. The images engraved on the inner face of the bench in combination with the size and structural features of the building, suggest that this must have been a place for special gatherings.

[The] principal human figure holds its phallus in its right hand… The rounded protrusions on the upper end of the legs appear to represent the knees, as if bent forward while sitting, and provide perspective. Although the head is damaged, a round face, large ears, bulging eyes and thick lips are evident. In particular, a triangular-shaped necklace or neckband is notable. This male figure is faced on each side by two leopards which are depicted in profile. Their mouths are open, the teeth visible, and their long tails are curled up towards the body. The leopard to the west is depicted with a phallus, whereas the other is not. 66

The Sayburç relief depicting a man between two felines (Photo: B. Kösker, CCBY4.0)

Karahan Tepe

In Episode 5 of my Netflix documentary series Ancient Apocalypse, after taking viewers to Gobekli Tepe, my next stop is Karahan Tepe, a site I first visited in 2014 before any excavation had been done there. Here’s how I introduce it:

Gobekli Tepe isn’t the only complex dating back to the end of the last Ice Age that’s recently been discovered here. In 2019 Turkish archaeologists began excavations at another site about an hour’s drive east called Karahan Tepe and uncovered something unexpected.

Lead archaeologist Professor Necmi Karul believes that this site is around the same age as Gobekli Tepe and could be even older… The main chamber does feature t-shaped pillars and megaliths, but one edge is carved out of the bedrock and it’s large enough to hold dozens of people.

A brief exchange follows between the Professor and myself in which we agree that this most likely would have been a setting where communal gatherings took place. In an aside to viewers, I then reiterate:

Karahan Tepe seems to be some sort of ritual gathering space. The carvings on the walls aren’t as well executed as those at Gobekli Tepe. But we do see robed figures. Could they represent the site’s true architects?

Professor Karul leads me into a curious side chamber 8 metres by 6 metres and 2 metres deep. Ten pillars resembling erect phalluses have been purposefully and skilfully carved directly out of the bedrock, with an 11th freestanding pillar in pride of place.

The chamber is dominated by an imposing and mysterious sculpted head, with human-like features, protruding from the bedrock at about shoulder height. “It’s a human head, taken from… out of the bedrock,” Karul observes, before adding: “It looks like a snake head”.

“A human-headed snake?” I venture.

“Yeah, maybe,” Karul replies.

The Professor tells me that he and his team have found no evidence of farming at Karahan Tepe. The people who built this complex were definitely still hunter-gatherers.

Graham Hancock: The notion used to be that agriculture came first, and then it allowed people to settle and create places like this, but, if I understand you correctly, you’re saying that settlement came first.

Professor Karul: Settlement came first… They are hunter-gatherers. And then they start to produce life. They changed the uh, building, they changed the… technology, etcetera.

Graham Hancock: A kind of, uh, revolution in ideas?

Professor Karul: It’s, uh, we can call it a revolution.

When I visited Karahan Tepe with Professor Karul in 2021, only two chambers had been excavated there. But ground penetrating radar had revealed at least 20 more chambers that had yet to be explored. Since then, several of these chambers have indeed been excavated and the site has been relatively dated to the Late PPNA and early PPNB,67 with refinements pinpointing the period 9400 to 8200 BC.68 These dates are roughly contemporary with those of Gobekli Tepe while suggesting that the latter’s monumental Enclosure D might perhaps be two or three centuries older than the megalithic and pillared elements of Karahan Tepe. Such comparisons may be temporary – it is estimated that only around 1 per cent of Karahan Tepe has yet been excavated.69 However, Professor Karul has already seen enough to be confident that architects and engineers with advanced skills must have directed works at the site:

“the very skilful processing of bedrock reveals an impressive prehistoric architectural engineering. Building multiple structures with different purposes is the reflection of a complicated belief system. It’s not possible to talk about religion in its true sense, but we see a set of distinct, limited rituals that are radically set forth.”70

Since Karahan Tepe features not only large “special” buildings capable of accommodating public gatherings and rituals, but also structures that are unambiguously domestic dwelling places, Professor Karul remains firmly of the view that permanent settlement came before, not after agriculture:71

“Now we have a different view on history. Our findings change the perception, still seen in schoolbooks across the world, that settled life resulted from farming and animal husbandry. This shows that it begins when humans were still hunter-gatherers and that agriculture is not a cause, but the effect, of settled life…”72

Professor Mehmet Özdoğan, an archaeologist at Istanbul University, believes that it will take time for the scientific community to digest and accept Karul’s game-changing research;

“We must now rethink what we knew—that civilisation emerged from a horizontal society that began raising wheat because people were hungry—and assess this period with its multi-faceted society.”73

Moreover, this is a rethink that matters because:

“The foundations for today’s civilisation, from family law to inheritance to the state and bureaucracy, were all struck in the Neolithic period.”74

In other words, the much vaunted, and now essentially global, advanced civilization of today has its roots in a civilization (Turkish authorities are already calling it the Tas Tepeler – “Stone Hill”s – civilization75) that begins to become archaeologically visible in Southwest Asia more than 12,000 years ago.

There is, of course, much more to say about Karahan Tepe than is called for in this brief update. However, one particularly important point remains to be mentioned. Professor Karul is confident that when Karahan Tepe was finally abandoned in the 9th millennium BC, some 1500 years or so after it was founded, its last inhabitants deliberately buried large parts (if not all) of the site – “as you would a person who has died”.76

In an extensive article, Karul draws attention to what he calls “the phenomenon of buried buildings”, particularly prevalent in the Near East and Anatolia77 and pinpoints the buried buildings of Karahan Tepe as a prime example of this more widespread phenomenon.78

Because so much of the site remains to be excavated, Karul is careful to point out that no domestic structures have yet been found: “All structures exposed at present are special buildings, evidently intentionally filled in.”79

He focuses on the Structure nominated AB and also, more amusingly, “The Penis Chamber”, the 2-metre deep semi-subterranean chamber with its rock-hewn phallus-like pillars, described earlier, that I visited while filming Ancient Apocalypse.

“Structure AB,” concludes Karul, “was completely carved into bedrock and intentionally filled.”80 Moreover it:

“was built for special purposes, with phallus-shaped pillars designed and formed from the beginning and a human head shaped from the bedrock… As a matter of fact, there are no domestic elements in the building. It is understood that the building was intentionally filled…in a series of sequential procedures. It is difficult to estimate how long this process took, but it can be assumed that it did not transpire over an extended period.”81

Karul’s insights here are relevant to a similar issue now being raised about Gobekli Tepe: Were its megalithic enclosures intentionally buried or not? This is a matter we’ll return to because of the great bearing it has on understanding the meaning and purpose of all the buried structures of the Tas Tepeler civilization.

Cyprus (updated 1st August 2024)

The Tas Tepeler civilization, which began to take a recognisable shape and to spread out across a wide area in the 11th millennium BC, was not only confined to the mainland of Southwest Asia. Whoever these people were, and however they acquired their skills, they were also seafarers and navigators…

Even at the Last Glacial Maximum around 21,000 years ago, when sea-levels were at their lowest – roughly 120 meters (400 feet) below today’s level – Cyprus, surrounded as it is by great deeps, always remained an island.82

In a paper published in the Journal of Maritime Archaeology in 2020,83 A. Bernard Knapp, Professor of Mediterranean Archaeology at the University of Glasgow and Honorary Research Fellow at the Cyprus American Archaeological Research Institute, writes:

There can be no question that prehistoric seafarers sailed between the Levantine and/or Anatolian coasts and Cyprus some 12,000 years ago, possibly several times per year, in order to transport large ruminants like weaned calves or small wild boar on boats much more sophisticated than we might imagine… Currently, however, we still do not know whether increased seafaring predated the Younger Dryas84 [for which Knapp prefers dates of “ca. 10,700–9600 Cal BC”].85

What we can be sure of, however, Knapp continues, is that:

“Those who undertook these maritime ventures had the ability to design and construct seacraft and to navigate, most likely on a seasonal basis, across the open sea from some adjacent mainland, be it some 50–60 km from the nearest point in Anatolia or about 95 km from the nearest point in the Levant.”86

A year later, in August 2021, Dr Evangalos Tsakalos, an environmental scientist who specialises in luminesce dating, together with a team of other experts, published a paper in the journal Current Anthropology87 — with the stated objective of attempting to fill in an apparent “gap” of about 1,500 years in the archaeological timeline for Cyprus between the earliest evidence for a human presence at “the Late Epipaleolithic site of Akrotiri Aetokremnos (ca. 10,500 cal BC)” and around 9000 BC.88 For this purpose, they deployed Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) dating,89 a technology that provides a measure of time elapsed since sediment grains were deposited and shielded from further light or heat exposure.

The results published in Current Anthropology did add confidence to the few existing carbon dates for the period, but—in my view— did not significantly broaden the picture despite claims by the researchers to the contrary.90 Indeed, the use of loose and evasive language, and of named chronological periods that are defined differently by different archaeologists, only serves to complicate rather than clarify matters.

After the single clear statement, cited above, that constrains the oldest known human settlement of Cyprus to Akrotiri Aetokremnos around 12,500 years ago, the paper by Tsakalos et al. waxes waffly and vague when it comes to pinning down exact dates. Here are some direct quotations:

This study places the campsite of Roudias in its temporal setting using optically stimulated luminescence dating. Absolute ages (ranging from 7.2 plus or minus 1.3 to 12.8 plus or minus 1.6 ka) provide evidence for the duration of the occupation of the Roudias site from the Late Epipaleolithic (or even earlier) to the Late Aceramic Neolithic, but more importantly, they push back the time of the first colonization of Cyprus and the onset of seagoing practices in the southeastern Mediterranean…91

Human visits to Cyprus would require suitable seafaring technology [since] the distance between Cyprus and Anatolia remained at least 30– 60 km even at the lowest sea level. Nevertheless, it seems that people had already found their way to Cyprus during what is termed the Late Epipaleolithic (ca. 11,000–9800 cal BC) and Pre-Neolithic (ca. 9700–8300/8200 cal BC).92

Voyaging to the island came at a time when climatic and other environmental factors perhaps forced the first visitors (Late Epipaleolithic hunters and gatherers of the twelfth and eleventh millennia cal BC) to become more mobile during the cold episode of Younger Dryas (ca. 12,900–11,700 years BP).93

The older OSL ages from Roudias (sample VR-04) support the hypothesis that the colonization of Cyprus could date to not only before the arrival of the first farmers (ninth millennium BC) but also several millennia back in the Late Epipaleolithic, signifying a much older seafaring tradition in the eastern Mediterranean. Permanent habitation entailed constant connections with the mainland, with repeated seafaring in the open seas. It seems that as early as the Late Epipaleolithic, navigation skills had already improved to the point of enabling eastern Mediterranean hunters and gatherers to undertake colonizing expeditions that probably involved the transportation of groups of people over maritime crossings in the range of 30–60 km; prior signs of comparable activity are generally less evident.94

Because the OSL dates in the Tsakalos study have such extensive margins of uncertainty, it is difficult to be sure exactly what they “support”. For example, the first occupation date for the campsite of Roudias is given as “12.8 plus or minus 1.6 ka”. I am not the only reviewer to ask what this actually means. In a comment on Tsakalos et al., archaeologist Ron Shimelmitz of the University of Haifa writes:

The authors may be in the right in claiming that the date of 12.8 plus or minus 1.6 ka marks the earliest human presence on the island. However, it is also important to keep in mind that OSL dates are characterized by relatively wide margins of error, amounting to more than 10% in the present samples. Under these circumstances, the primacy of Roudias is uncertain, and the early part of the site may fall equally well within the slightly later range of Akrotiri, 12,096–11,504 cal BP.95

As we’ve seen, the Tsakalos paper gives a carbon date of “ca 10,500 cal BC” for Akrotiri, i.e. around 12,500 years ago. Shimelmits downgrades this to a range between 12,096 and 11,504 years ago.

Similarly, when Tsakalos writes: “Nevertheless, it seems that people had already found their way to Cyprus during what is termed the Late Epipaleolithic (ca. 11,000–9800 cal BC),” he is not offering a precise date for their first arrival but rather a range of dates between 13,000 years ago and 11,800 years ago.

Last but not least, Tsakalos envisages the “first visitors… Late Epipaleolithic hunters and gatherers of the twelfth and eleventh millennia cal BC” as perhaps sailing to Cyprus during the Younger Dryas cold episode (which he puts at around 12,900 to 11,700 years ago) “when climatic and other environmental factors” had forced them to become more mobile.

Perhaps it’s just the loose language and the huge margins of uncertainty, but the intuition Tsakalos et al. offer at the end of their August 2021 paper does not seem fully justified by the OSL evidence when they write that “colonization of Cyprus could date to not only before the arrival of the first farmers (ninth millennium BC) but also several millennia back in the Late Epipaleolithic, signifying a much older seafaring tradition in the eastern Mediterranean.”

In August 2021 this interesting speculation seemed like a bit of a reach. But in May 2024 a new analysis of the muddled chronology of Cyprus was published in the Proceedings for the National Academy of Sciences which adds muscle to the proposal that the island was first settled in the Late Epipaleolithic – and indeed before the onset of the Younger Dryas cold episode.

Titled Demographic Models Predict End-Pleistocene Arrival and Rapid Expansion of Pre-Agropastoralist Humans in Cyprus, the paper is co-authored by multi-disciplinary team of climate scientists, ecologists, geologists and archaeologists.95a While they do not offer new radiocarbon or OSL dates, the co-authors applied a sophisticated resampling algorithm to existing dates for the ten oldest archaeological sites in Cyprus:

“Using the latest archaeological data, hindcasted climate projections, and age-structured demographic models, we demonstrate evidence for early arrival (14,257 to 13,182 calendar years ago) to Cyprus… Large groups of people (1,000 to 1,375) arrived in 2 to 3 main events occurring within 100 years to ensure low extinction risk. These results indicate that the postglacial settlement of Cyprus involved only a few large-scale, organized events requiring advanced watercraft technology…”95b

The co-authors go on to remind us that their proposed entry window of 14, 257 to 13,182 years ago:

“predates both the Younger Dryas and the onset of the Holocene. Even if the earliest date of Akrotiri Aetokremnos is removed, Signor–Lipps correction of the radiocarbon series still places the window of arrival at 12,757 to 13,162 years ago (i.e., firmly into the terminal Pleistocene), prior to the earliest appearance of agro-pastoralist communities on the mainland.”95c

It is no easy matter to settle a previously uninhabited island and make a long-term success of the venture. “Thus,” the paper’s co-authors conclude:

“the large founding population we estimated is best viewed as an ‘insurance policy’ against the likelihood of extinction. Our analysis on the frequency of arrivals also supports the idea of large, and by inference, planned migrations to the island. In other words, many small sporadic forays of unconnected people over long periods of time were unlikely to support a permanent population.”95d

A project involving organized migrations aboard vessels capable of carrying large numbers of settlers across more than 50 kilometres of open water is the sort of undertaking that we would normally associate with a civilization. And what intrigues me is that this project appears to have been initiated just before the Younger Dryas. Exactly how long before cannot be computed because of dating uncertainties and we find ourselves once again in inexact chronological territory – i.e. a broad entry window between 14,257 and 13,182 years ago refined, with the removal of a single disputed date, to a narrower window between 13,162 years ago and 12,757 years ago – the latter actually after and not before the onset of the Younger Dryas. (Although different scientists give marginally different dates for the Younger Dryas, most would now agree that it began somewhere in the century between 12,900 years ago and 12,800 years ago).

Abu Hureyra: The Airburst that Changed Everything

Located in Syria, some 325 kilometers south of Gobekli Tepe and some 615 kilometers northeast of Jericho, Tell Abu Hureyra was submerged by the waters of Lake Assad following the completion of the Tabqa Dam in 1974. Before submergence, however, two seasons of intense rescue archaeology were completed under the directorship of Dr Andrew T. Moore.96 The result was a treasure trove of archaeological materials, human remains, animal bones, potsherds, artefacts and extensive samples of soil sediments from the site, all carefully preserved and now – still under the direction of Andrew Moore — available for study by scholars all around the world.

The reader will recall that Abu Hureyra was first settled around 13,400 years ago. Thereafter, other than brief periods of desertion, it remained continuously inhabited for several millennia by people “who initially practised hunting-and-gathering in the late Epipaleolithic… before transitioning to full-scale farming by the early Neolithic.”97

What this means, in short, is that the inhabitants of Abu Hureyra passed through the Younger Dryas…

Experienced the Younger Dryas…

And thanks to more recent work on the Abu Hureyra material, carried out from 2020 onwards by Andrew T. Moore and a team of other experts, we now have a very good idea of exactly what the ancient inhabitants of Abu Hureyra experienced when the Younger Dryas struck them down— in spectacular, indeed almost Biblical, fashion…

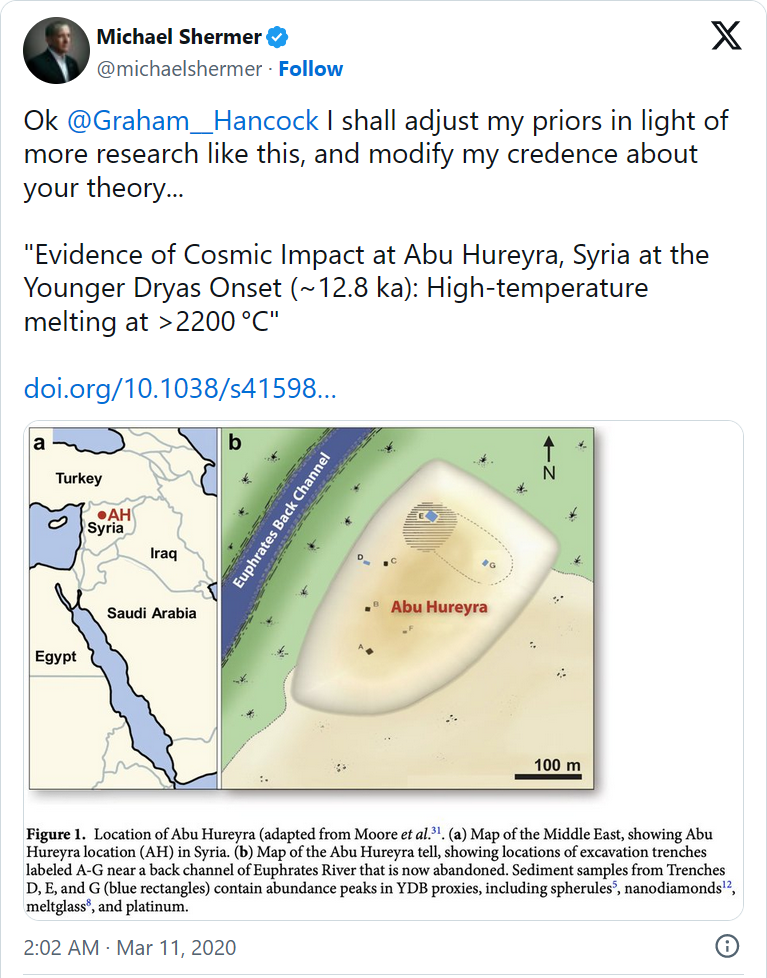

In summary, the new research reveals that Abu Hureyra was completely destroyed, incinerated and briefly depopulated,98 by a horrific aerial explosion that occurred close by somewhere between “12,835-12,735 cal BP”99 — a date range that Moore et al. average at “~12.8 ka”, i.e. at approximately 12,800 years ago, thus straddling the Younger Dryas Boundary.100

The cause of this explosion was not a nuclear bomb — although, from the magnitude of its effects, it might as well have been:

At Abu Hureyra (AH), Syria, the 12,800-year-old Younger Dryas boundary layer (YDB) contains peak abundances in meltglass, nanodiamonds, microspherules, and charcoal… High YDB concentrations of iridium, platinum, nickel, and cobalt suggest mixing of melted local sediment with small quantities of meteoritic material. Approximately 40% of AH glass display carbon-infused, siliceous plant imprints that laboratory experiments show formed at a minimum of 1200°–1300 °C… Alternately, melted grains of quartz, chromferide, and magnetite in AH glass suggest exposure to minimum temperatures of 1720 °C ranging to >2200 °C. This argues against formation of AH meltglass in thatched hut fires at 1100°–1200 °C, and low values of remanent magnetism indicate the meltglass was not created by lightning. Low meltglass water content (0.02–0.05% H2O) is consistent with a formation process similar to that of tektites and inconsistent with volcanism and anthropogenesis. The wide range of evidence supports the hypothesis that a cosmic event occurred at Abu Hureyra ~12,800 years ago, coeval with impacts that deposited high-temperature meltglass, melted microspherules, and/or platinum at other YDB sites on four continents.101

Moore et al. see the evidence from Abu Hureyra as strongly confirming the controversial but solidly grounded Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis (YDIH). Indeed, they write:

This… event at Abu Hureyra is an integral part of the Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis that posits multi-continental cosmic airbursts/impacts recognized at >50 locations spanning >100 million km2 across North and South America, Europe, Asia, and Africa.102

Moore et al. clarify that what happened over Abu Hureyra around 12,800 years ago was not an impact but an airburst – “a near-surface atmospheric detonation by a cosmic object, resulting in a high-temperature, hypervelocity jet of ionized gases and debris that reaches Earth’s surface.103

Since I have already written extensively about the Younger Dryas Impact hypothesis in Magicians of the Gods (2015) and in America Before (2019), and since it was the central focus — indeed, it was the eponymous “ancient apocalypse” — of my 2022 Netflix documentary series, I will not elaborate on its broader details here. By way of a refresher, however, here’s how Moore et al. summarise the hypothesis:

“It is proposed that numerous fragments of a giant comet collided with one hemisphere of the Earth ~12,800 years ago, causing numerous airbursts/impacts spanning several hours. We posit that multiple airbursts/impacts by fragments of this comet collectively ignited wildfires on a hemispheric or global scale. If there were larger, crater-forming impactors, they may have impacted the world’s oceans, produced transient craters, or formed craters that are as yet undiscovered. For the hemisphere exposed to the incoming comet, the mean distance of any point from a multi-megaton impact by such a body would have been a few tens of kilometers, meaning that a large percentage of the surface of one hemisphere would have been directly affected by thousands of these airbursts/ impacts. At the same time, there would have been an influx of millions of tons of cometary dust in the form of carbon-rich aerosols and water vapor over the few hours of the encounter (compared to typically 50 tons/day), along with soot from the extensive wildfires. Together, these particulates triggered climatic instability, inducing long-term cooling (impact winter, followed by the onset of the Younger Dryas episode) enhanced by creating high-altitude, insolation-blocking ice crystals.”104

To return to the specifics of Abu Hureyra, it’s best if I continue to allow the researchers to speak for themselves:

Our multiple analyses have revealed the potential presence of fractured quartz grains limited to the YDB cosmic impact layer in the Abu Hureyra section. It is important to note that this dark layer had previously been identified… based on abundance peaks in nanodiamonds, magnetic micro-spherules, high-temperature meltglass, carbon micro-spherules, platinum, nickel, cobalt, chromium, and other potential impact-related proxies… This assemblage of inferred impact-related proxies and the size characteristics of specific proxies, such as meltglass, implies the presence of a nearby cosmic impact. Although no known crater is near Abu Hureyra, the impact hypothesis does not require one. Most of the same inferred proxy evidence observed at Abu Hureyra has been found at accepted impact events with no known confirmed craters, including the Dakhleh Oasis in Egypt, the Australasian tektite field in SE Asia, and the Atacama Desert…

The large size of some AH micro-spherules and meltglass (≥1 cm in diameter) indicates that whether the bolide at Abu Hureyra created an airburst or crater, ground zero may have been close to the village because such large fragments are unlikely to have traveled far. The evidence suggests that meltglass remained molten long enough to coat and burn into bones, debitage, and clay plaster within the village.

Because melted proxies are more abundant at AH than at Tunguska [the Tunguska cosmic airburst over Siberia on 30 June 1908105], the AH bolide’s energy is estimated to be greater than ~30 Mt, which is much larger than estimated for Tunguska (~5 to 15 Mt).106

This investigation is the first to have identified and described shock-fractured quartz specific to the YDB cosmic impact layer at the onset of the Younger Dryas climate episode in the Abu Hureyra archeological site, thus verifying this as a cosmic impact layer.107

The YDB layer in sample E301 contains a large concentration peak of soot at ~6 wt% of total sediment … In comparison, low soot concentrations… were found in levels 402– 406 above the YDB and…in sample ES15 just below the YDB.

Several YDB-age fragments of clay plaster were found embedded into the surfaces of AH meltglass, melted at high temperatures, or partially coated with AH meltglass. Unaltered clay plaster was common in, above, and below the YDB, but glass-coated clay was found only in strata marking the YDB event, making its presence highly anomalous.108

This is the first known report of impact-related meltglass partially coated onto bones in faunal archaeological assemblages, debitage from toolmaking, and human building materials. No similar material was observed in thousands of years of anthropogenically deposited sediment above the YDB layer.109

A fundamental change in village construction… dates to the onset of YD climate change at 12,800 cal BP. During the late Allerød, immediately before the YD onset, the villagers lived in pit dwellings built close together, each composed of several connected sub-circular chambers. When the village was destroyed, the pits became filled with non-laminated debris. This pit debris contains spherules, nanodiamonds, platinum, iridium, and high-temperature meltglass derived from melted local sediment… When the village was rebuilt, the people abandoned the previous pits and constructed timber and reed huts over them with flat floors at ground level, representing a significant change in architectural style.110

Pit infill at AH contains YDB peak abundances of plant-imprinted meltglass, glass-splattered debitage and animal bones, charcoal, soot, platinum, iridium, and nickel. Later, villagers levelled the debris and built a different style of hut that lacked interior pits, meaning that the old-style pit houses were never reconstructed. This sudden transition to huts without pits represents a significant, highly unusual departure from the previous 600-year-old pit-style architectural tradition.

The collective evidence indicates that AH melt-glass is not anthropogenic in origin. If it were, meltglass would be found in high concentrations throughout the sedimentary column, especially in the youngest strata, where human populations were the largest. Instead, AH meltglass is only occasionally found in minor quantities above the YDB, and most strata contained no meltglass. Meltglass inside hut pits is found within unstratified, monolithic deposits that do not appear to have been deposited anthropogenically but rather are inferred to have been rapidly deposited as the huts were destroyed by the blast wave from the near-surface airburst.

Based on melted minerals embedded in meltglass, we propose that AH meltglass was exposed to temperatures far above the melting point of local sediment…The evidence suggests that ambient temperatures around the meltglass rose to >2200°C, chromite’s melting point and quartz’s boiling point.111

In summary, the stratigraphic data from AH show that sediments of YDB age exhibit major abundance peaks in charcoal, charred seeds, charred fruits, carbon micro-spherules, soot, and carbon-infused meltglass. The amount of charred material in YDB age sediments is by far the highest concentration observed in the AH stratigraphic record and represents the largest biomass-burning episode for the entire 3100-year sedimentary record, ranging from ~13,300 cal BP to 10,200 cal BP. The large accumulation of burned carbon of YDB age suggests incineration of wood, reeds, and grasses used for village hut construction but may also include the influx of nearby burned plant material from the Euphrates floodplain. This collective evidence is consistent with the hypothesis that the village was incinerated and destroyed ~12,800 years ago.112

Prior to the publication of the first Moore et al. paper in 2020, “Evidence of cosmic impact at Abu Hureyra, Syria at the Younger Dryas Onset (~12.8 ka)”, the YDIH had been met with a great deal of wholly unnecessary skepticism. But now the tide had begun to turn, as witnessed in this generous Tweet of 11th March 2020, reproduced below, from my long-time opponent Michael Shermer, Editor of The Skeptic magazine:

To be clear, the YDIH is not “my” theory, nor have I ever claimed it to be “my” theory. When I reference it, I always credit it to the team of scientists (now known as the Comet Research Group) whose members first began to formulate it decades ago, and for whose work I have long been a vocal public advocate.

Another sign of the growing acceptance of the YDIH, despite the protests of a hard-core band of opponents, was James Lawrence Powell’s trenchant 2022 paper “Premature rejection in science: The case of the Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis.”113

Abu Hureyra was by no means the only site in the general region of Gobekli Tepe to be affected by the Younger Dryas cataclysm. On the contrary, “across large areas of Western Asia, patterns of settlement and economy among contemporary hunter-gatherer groups were disrupted.”114

In the case of Abu Hureyra, however, although the proposed airburst “coincided with a significant decline in local populations and led to architectural reorganizations of the village”115, it’s interesting to note that the destruction of the village was followed promptly by its reoccupation, at which point its returning or new inhabitants quite suddenly adopted farming “while continuing to exploit wild plant and animal foods. Their crops included rye, lentils, and einkorn wheat (literally ‘single grain’), enabling them to maintain year-round occupation of the village.”116

In the following millennia:

the villagers developed a mature farming system from this nascent agricultural economy. They added more crops to the mix, including barley, bread wheat, and chickpeas, and also the main species of domestic animals, first, sheep and goats and then later, cattle and pigs. Sedentary village life supported by productive farming enabled the population to increase, such that in its later stages, Abu Hureyra had several thousand inhabitants and covered up to 16 hectares.

We can now identify the Younger Dryas cooling event, felt widely across the planet, as a causal mechanism for the changes at Abu Hureyra, including the beginnings of domesticated plant cultivation.117

The scientists behind the YDIH are of the view that, for most of the past 20,000 years, the Earth has been in interaction with the debris stream – now known as the Taurid Meteor Stream – of the same comet that sparked off the cataclysm of the Younger Dryas around 12,800 years ago:

Modeling of Taurid disintegration leads to an estimation that during the last 20,000 years, Earth possibly experienced several “meteor hurricanes” with kinetic energies between 3,000-40,000 megatons (Mt) and durations of a few hours to a few days… Given that a debris trail dense enough to produce the YDB airburst proxies may be 1000 to 10,000 Earth radii in length, Earth may have passed through such a debris trail multiple times, approximately once per century near 12,800 cal BP.118

Once per century?

Or maybe more.

With events from which we are separated by more than 12,000 years, it may never be possible to be sure.

What we can be sure of, however, as we gaze back across that vast span of time with the benefit of hindsight, is that this was an epochal moment in the evolution of the global technological civilization that spans the Earth today.

Indeed, it has frequently been hailed as the moment when “we” began.

But was it?

Bridging a troubling gap

Since I first suggested that the megalithic enclosures of Gobekli Tepe were evidence that survivors of lost civilization had transferred technology, skills, and know-how to hunter-gatherers, I’ve been troubled by a “gap” in the hypothesis. The cataclysmic events at the onset of the Younger Dryas took place around 12,800 years ago, but work didn’t begin at Gobekli Tepe until 11,600 years ago, 1,200 years later. Surely the “survivors” couldn’t have lived for more than 1,000 years to pass on their knowledge to the builders of Gobekli Tepe – so in what form, carried by what vectors, was my supposed transfer of technology achieved?