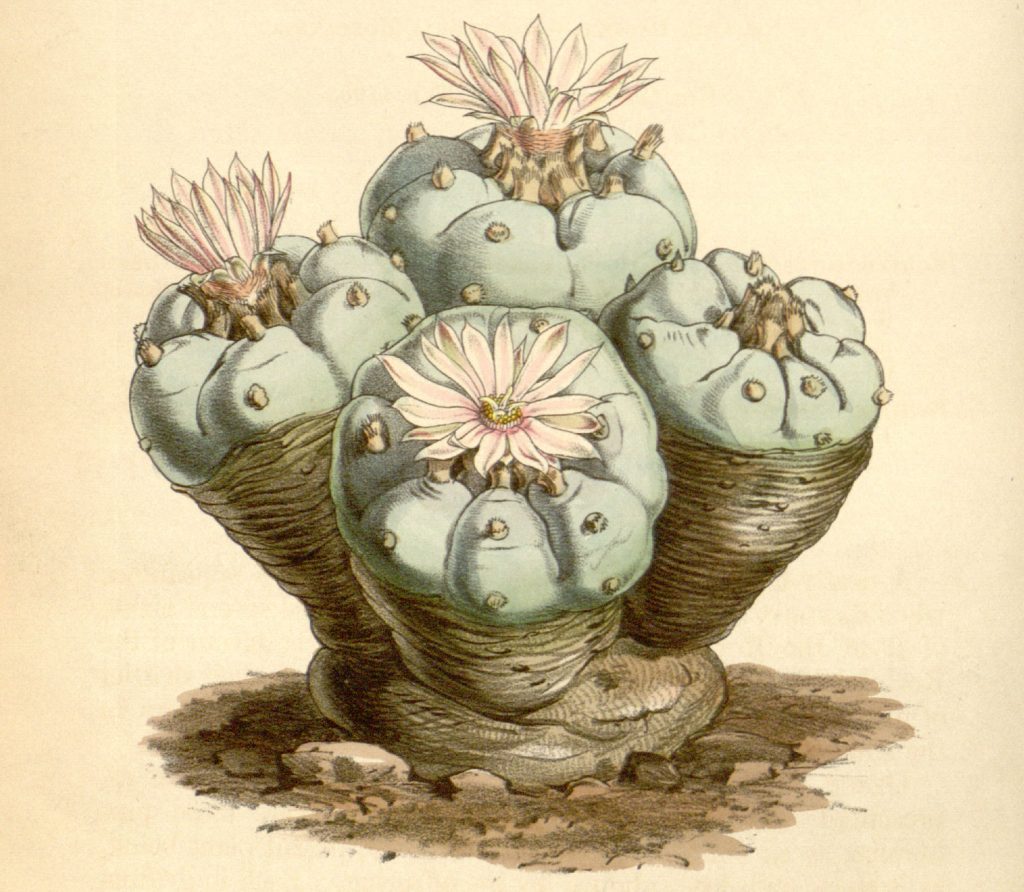

What is actually known about the psychoactive substance mescaline and its relationship to humans, considering a millennia old bond between the two? Although the scientific research into this question begun over a century ago in 1886 with German pharmacologist Louis Lewin’s publication on the Peyote, the psychological material on the subject was and still is rather limited.i The observed and recorded data collected during mescaline experiments conducted in clinical settings during the first half of the 20th century has provided little understanding of this phenomena overall. And the simple fact that mescaline is a naturally occurring alkaloid in both the San Pedro and Peyote cacti of Peru and Mexico, is hardly sufficient to explain its deepest bond with humans throughout history.

I intend to explore the existence of these mysterious plants and their purpose on Earth in my next book, which will be wholly dedicated to the sacred cactus and written from the perspective of 12 years of work with it in a shamanic way; but for now, I would like to present a brief overview of relevant themes relating to the sacred psychoactive medicine, and open conversation.

While neurologists, physiologists, biochemists, psychologists and psychiatrists were involved in the study of the mescaline phenomena and gathered some useful data, the research has not met the expectations of many individuals genuinely interested in the subject. This is most likely due to the fact that the experience of mescaline itself, rather than the chemical compound that triggers it, is responsible for the healing and inspiration the substance has to offer.

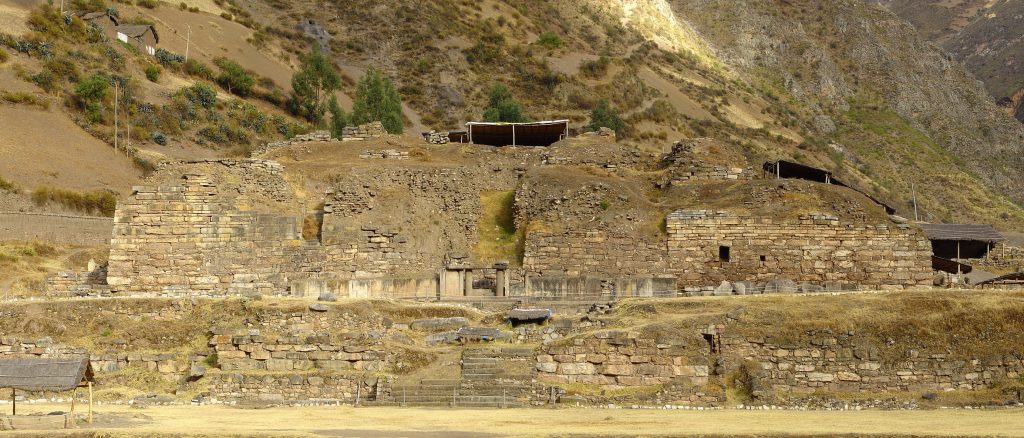

Both the san pedro and peyote cacti were used as sacraments for millennia, and the unbroken shamanic traditions of North and South America continue today. The oldest cultures known to history whose existence revolved around the sacred cacti were the Chavin of Peru and Huichol of Mexico. Although archaeologists confidently ascribe the Chavin period to between 1,200 – 200 BCE, the true age of this mysterious San Pedro culture could have had a much earlier beginning. The temple of Chavin de Huantar in Ancash, Peru, was ‘discovered’ in 1919, and stands as a silent witness to this mystery that will perhaps never be solved.

The Huichol Indians of Mexico, on the other hand, are the inarguable guardians of the ancient Peyote tradition. When travelling in both continents and working with natives, one is amazed to find cultures with such similar content but different ‘flavours’. A deeper immersion into this topic in its cultural context would yield a greater understanding not only of the subject matter but also of the basis for the formation of the first dynamic and living religion: shamanism; a religion fundamentally based in psychedelic experience.

The common academic view of these native cultures serves as a barrier between the West and the indigenous peoples, who possess practical knowledge on the subject; a knowledge that has been accumulated over thousands of years and passed down from generation to generation. This knowledge has been largely ignored by mainstream science. Perhaps the few words of the shamans spoken in whispers were found insufficient for the purpose of conducting an investigation using scientific methods to form a hypothesis about the phenomena, which predates reason. But even the shamans’ words should not be taken as a substitute for knowledge, for this can be achieved only directly from the experience – something that is generally avoided by scholars who feel they can write on the subject without participating in rituals themselves and actually ingesting the psychoactive plants. One can understand by means of mere logic that studies written on the subject of psychedelic experience cannot bear enough weight to result in a thorough understanding unless this is done.

The scholarly approach, based mainly on erroneous assumption, led to the common characterisation of shamanism as pathological behaviour, and mescaline as a substance that induces mental illness.ii But how far can research go when the results are presupposed, in this case for the purpose of understanding mental illness? By ascribing mescaline to the psychotomimetic, and comparing the shamanic state of consciousness with schizophrenia, psychiatry lost the trail from the start.

This whole area of research had to wait for Aldous Huxley, who I often quote and admire, to be taken to the next level. Huxley was introduced to mescaline in the spring of 1953; after taking it under the supervision of Humphry Osmond, an open-minded psychiatrist (whom in my opinion should be held as an example in the field), it became recognised for its extraordinary quality and the mystical state of consciousness that it facilitated; an experience which has been generally seen by mainstream psychiatry as a psychotic reaction of the intoxicated mind. And if the mainstream interpretation of the substance were the case, then the twelve past years of ongoing work with mescaline-containing cacti I’ve experienced–including nearly a thousand ceremonies lasting between 10 -14 hours, totalling over 10,000 hours–would have put me in a mental asylum sharing a room with Napoleons. Instead, I have raised a beautiful family, written books, helped people to reconnect with themselves, and find healing, balance and clarity in their lives.

But even Huxley, who was undoubtedly among the brightest intellectuals of the 20th century, did not grasp the difference between an isolated alkaloid and an ingestion of the whole plant in a shamanic setting. While admitting the mystical experience, he didn’t have a chance to fully immerse himself into the mystery found in rituals rather than clinical investigations. Perhaps during his time, the urgency to reveal its full healing potential wasn’t as acute as it is today. Although the ancient shamanic tradition–a global phenomenon since the beginning of time and precursor to religion at large–has always persisted, it has now resurfaced to a greater visibility, and perhaps for a specific reason. This, I believe, has to do with the self-destructive path humanity has taken. Being at a crossroad, we as a species can now decide our future. Further destruction of the natural environment and disconnection from our spiritual roots, fuelled by the ever-increasing influence of the technological era, will lead us into oblivion if not balanced with conscious living. And here is where the sacred Teacher Healer plants are coming to play. With their help, we are able to restore the balance within and consequently outside of ourselves. They can help us to realise our humanity beyond the social barriers of race, religion and social status and feel the unity with the rest of the natural world, realising the same love for life in all living beings; which in itself leads to respect and peaceful coexistence. On a more personal level, these Teacher Healer plants are capable of freeing a person from fears, which are often found at the root of depression. They can positively intervene in destructive behaviour, including drug and alcohol addictions, giving a person a second chance for a healthy, happy, ethical, and productive life.

Seeing this and other types of profound and lasting healing in practice over the years, it is rather mind-boggling for me to see mescaline–an alkaloid that consistently inspires contemplation and a deep ethical viewpoint–classified as a schedule 1 drug in the Western world under the claim of it being highly addictive and having no medical value, like heroin. Mescaline is not addictive and certainly has medical value that is hard to overstate. In the case of mescaline and heroin, we are not comparing oranges and apples, but oranges and toxic waste. Whether or not this insane prohibition was based on insufficient data, limited understanding or on a fear-based paranoia (something that extends to all psychedelics) is unknown. But what is known by practitioners, is that the medical and psychological effects caused by the administration of mescaline in an authentic, shamanic setting often results in an exceptional healing experience. A personal transformation of the individual can then have a positive impact on both the person’s life, their family and society at large; for a person is a constituent of their society, and an essential composite in its structure that plays a role in reshaping it inasmuch as society and culture shapes the individual.

Though the mescaline-containing cacti can serve as a catalyst for personal and societal change, they should never, in my opinion, be taken recreationally or carelessly. In doing so, the sense of the sacred communion and its potential for healing is diminished. Mescaline should be taken by people in shamanic settings with the right mindset, guided by an experienced person whose knowledge of these plants has not derived merely from books.

I didn’t want to spend years of my life acquiring academic credentials, so I chose the shamanic approach, which is more ambiguous and yet, I feel, more revealing. Instead of being preoccupied with the botany and chemistry of the plant and measurements and location of ‘hallucinations’, I chose to learn about it from the source, which is the shamanic experience itself.

An experience, however, should not be confused with an experiment, for the two are not the same. An experience is learning by involving yourself in something empirically – in this case in the shamanic ritual, which includes the ingestion of the whole plant and the intention to learn and heal. An experiment in this context is generally a scientific procedure undertaken to make a discovery or test a hypothesis that usually involves others on whom isolated alkaloids are experimented on. While Peruvian and Mexican tribes have experienced peyote and san pedro over thousands of years, scientists begun learning about mescaline at the beginning of the 20th century.iii And how did they begin experimenting? By subcutaneously injecting monkeys with large doses of mescaline, causing the poor, caged animals to reach catatonia by overloading their nervous systems with an experience they were unable to process; a creepy and barbarous method of study, most people would say. It would be more merciful, in my opinion, to force a monkey into bungee jumping or parachuting.

This unnatural and clinical approach to administrating mescaline was also applied to humans, who are more able to process stimuli, and have greater mental and emotional capacity to receive, express and assimilate the psychedelic experience than monkeys. Yet investigators were not brought much further towards understanding the phenomena at large, because the mescaline had been isolated from its biological body – the plant – which in itself was uprooted from its cultural context where it is respected, understood and held as sacred. In being alienated from itself and then administrated in an unnatural way by people whose psychological backgrounds do not support a spiritual perception of reality, the results of mescaline could only have been defective. And not only this, for the language spoken and understood by the shamans of Peru and Mexico for thousands of years was predictably interpreted as ‘chronic mescalinism’, psychosis and schizophrenia. In being preoccupied with causative factors for ‘hallucinations’ – the localisation of the experience and optical effects more than with the question of consciousness– science has missed the point. It took a high-profile individual, Aldous Huxley, to draw attention to the spiritual context of mescaline. Perhaps, due to his intense study of eastern philosophies, it wasn’t hard for him to see the parallels between mescaline and the mystical experiences, as related in the ancient texts.

Huxley writes about his experiences with mescaline in his epic book, The Doors of Perception, which took off like wildfire, sparking both delight and critique from spiritual leaders who have seen this as a shortcut to Enlightenment, and perhaps were even threatened by the immediacy of the spiritual awakening.

Although aware of the book, I had, by the time I sat down to read it, already experienced the mescaline-containing cactus san pedro for many years, and was admittedly looking for faults in Huxley’s writing. Instead, I found it to be a brilliant account, albeit not fully reflective of the magnitude of the experience, which would otherwise have been available under a different setting. Nevertheless, Huxley has definitely seen the essence and touched the heart of the mystical experience, to which mescaline served as the key, unlocking the ‘forbidden’ doors of perception.

As I had been interested in eastern spiritual paths long before I met shamanic plants, (the divine cacti of Peru and Mexico in particular) I could deeply relate to Huxley’s search and felt his passion for the direct spiritual experience of an objective reality. The stupendous beauty of the world engulfed with life and meaning, which is always present behind the veil of the ordinary perception of reality and can be gently lifted by the grace of the mescaline cacti, is that very same place that has been known for ages by the Sufis, sages and mystics of the East and West. Under the influence of mescaline revelation, one can be transported to the room in which Van Gogh was painting and writing. One can feel his heart and see through his mind. In the same way, one can find oneself sitting next to the Indian babas or walking along the path with a dervish. Not in a sense of being transported in time as such, but by becoming connected to the timeless spiritual teachings of the Near and Far East. The hidden meaning in the poetry of Rumi, for example, reveals itself in its depth.

Having used many substances and plants, sedatives, stimulants and psychedelics, and having searched for the path, both recreationally and intentionally over the many years, I can say with great certainty, from personal experience, that mescaline deserves a special place among all other psychoactive agents. The gratitude for its gifts, which have been received and perceived under its influence, are difficult to express and its teaching and wisdom I can hardly overstate.

I think it’s crucial for Western science and Eastern spiritual paths to expand their outlook and recognise the ancient plant-based shamanic traditions as a legitimate way to self-knowledge, personal healing and to the enrichment of our collective understanding of reality.

A few years ago, I was fortunate enough to be chosen as a guide to the mescaline realm by representatives of the Western scientific world; one German biologist and another Russian doctor of science, whom I took to visit a few places in Peru and Bolivia, including some ancient caves. I was also given the opportunity to introduce to mescaline a well-known and respected Yoga teacher Karta Singh, one of the first students of Yogi Bhajan who brought Kundalini Yoga to the West in 1968. You can read about it in the book Meetings with Sergey Baranov: Sacrifice Your Fears for Your Vision by Frederic Swiercz.

What I found particularly interesting was that the spiritual teacher and the doctor of science were very different and interesting people coming from parallel environments and backgrounds, and both expressed their highest appreciation and gratitude for this new experience and for an opportunity to see the world through a different lens. Certainly, a chapter in my next book will be dedicated to a broader understanding of evolutionary shamanism and its potential role as a unifying force between religion and science – two major and important aspects of the human experience.

It is time for unity. There is no healing in confrontation and competition. Cooperation and an expansion of consciousness should be chosen instead. By uniting different disciplines, we can make a greater contribution to the overall understanding of reality and ourselves, thus affecting positive change in the world.

It was encouraging to receive a number of emails from professors of psychology whom have shown an interest in the subject after watching the interview I recently gave to Dr Van Nues, PhD from Northern California. You can watch it here: On The Shamanic Path: Shrink Rap Radio Interview with Sergey Baranov

Please also like and share our newly created Facebook page, which is dedicated to the cause: Facebook.com/HuachumaWasi

References

i Lewin, Louis, ‘Ueber Anhalonium Lewinii’. Archiv für Experimentelle Pathologie und Pharmakologie, 1888.

ii See for example: James, William, Varieties of Religious Experience, London, 1902

Devereux, James, Shamans as Neurotics, American Anthropological Association, 1961.

Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry, ‘Mysticism: Spiritual Quest of Psychic Disorder?’. Committee on Psychiatry and Religion, New York, 1977, pp. 705-825.

iii See for example: Kluver, Heinrich. Mescal and Mechanisms of Hallucinations, University of Chicago Press, 1928: “…the importance of mescal for psychological research cannot be questioned.”

Sergey Baranov is the author of PATH a book that will be of interest to any spiritual seeker who seeks honesty above all else. Having lived in various countries and grown up in different cultures, Sergey has gained an understanding of the essential, a core commonality of human experience that lies beneath the differences to be found in every culture. By walking different paths and seeing through their limitations, Sergey found shamanism as a unifying path for all people regardless of their cultural background. He currently lives in Peru with his family where he conducts monthly San Pedro retreats.

You can find out more in his book Path, available on Amazon, or follow Sergey on Facebook at Facebook.com/HuachumaWasi

Very interesting,Jay Stevens book storming heaven is also a compelling read