- The Labyrinth and the Travelling Bag: Part 4 of Images from Göbekli Tepe and Other Neolithic sites reflected in Sumerian pictograms and texts

- Land of Milk and Psychedelic Honey: Part 3 of Images from Göbekli Tepe and Other Neolithic sites reflected in Sumerian pictograms and texts

- Images from Göbekli Tepe and Other Neolithic sites reflected in Sumerian pictograms and texts – Part 2. Pagan Wings and Sailors’ Feet

- Images from Göbekli Tepe and other Neolithic sites reflected in Sumerian pictograms and texts – Part 1. The Pillar and the Snake

There can be no getting away from the ancient handbag. Whether carried by a giant Mesopotamian birdman in one place or held aloft by a Mesoamerican voyager in another, the bag was ubiquitous in ancient iconography. And it had a quite uncanny way of travelling between continents at a time when no-one was supposed to know how to sail across vast oceans.

This plethora of images begs the question of why the bag doesn’t have a more prominent place—or any place at all, for that matter—in at least one or two of the equally numerous ancient Sumerian texts. Then again, those who have – even superficially – studied my two translations, The Story of Sukurru and Maestro of a Lost World, will know the answer to that reasonable question: It does. There is no unexplained dissonance between ancient Mesopotamian images and their written history. The bags had their importance. What might appear to be a glaring omission stems entirely from fundamental errors in modern interpretations. That said, can I pride myself on having got to the bottom of it? Have I found out everything there is to know about the contents of all those bags? Perhaps not. But at least now we can attempt to look inside without indulging in the sweet syrup of pure conjecture.

Lest we lose the thread

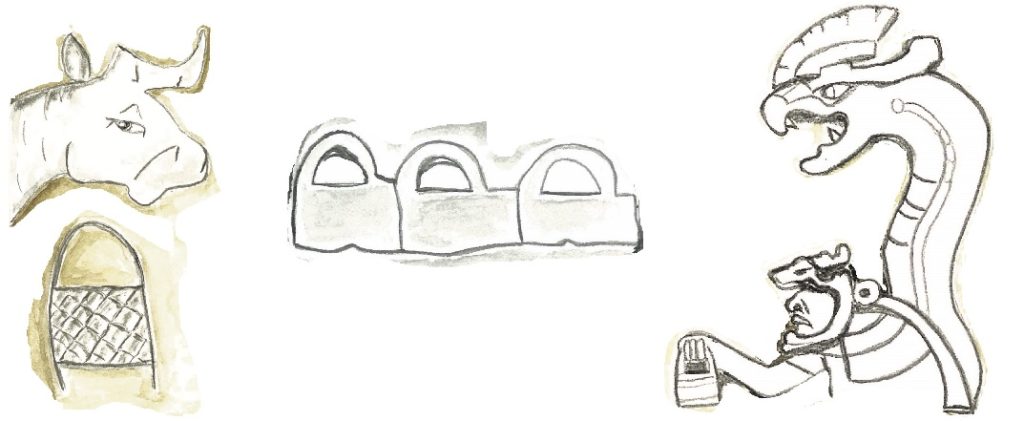

The above images have already been discussed in the past three articles of this series. For memory:

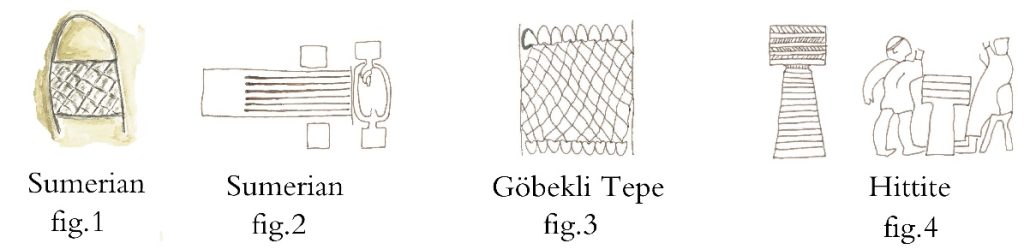

– fig.1: woven basket on a small clay tablet dating to ca.3350 BC.

– fig.2: imprint of a cylinder seal with a weaving scene from the same period or earlier.

– fig.3: woven net of snakes carved onto a pillar at Gôbekli Tepe ca.9600 BC.

– fig.4: T-shaped pillars bound in cloth or cords on the exterior wall of a Hittite temple at Alaca Höyük and on a Hittite vase, both ca.1600 BC.

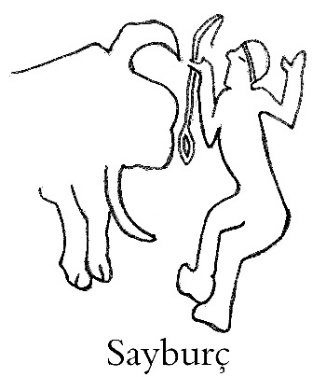

A direct connection throughout the ages between bulls and weaving can be added into the mix. Fig.1 has a bovine head (JIR3) placed above the woven basket. The two Hittite images (fig.4) both have imposing figures of bulls close by. Then there is the Sayburç bull-leaping scene ca.9000 BC, where a rope or a snake is held up to the bull’s horns (see part 3).

All of these images are woven together by a single invisible thread of meaning, coming from and leading to somewhere or other. Is there an astronomical reference to be found in them? And what, if anything, does a bag have to do with it all? What have we missed?

It’s already a widely accepted fact that the Sumerian writings provided the source material for certain later biblical tales, most notably that of Noah’s ark. But it’s less well known that they are also the ultimate source of the Greek myths. One of numerous occulted Gordian knots preventing us from moving forward to a better understanding of our most ancient history was touched on in the notes to part 3: i.e. the arbitrary decision to give a previously unheard-of identity, that of ‘Sumerian’, to the roots of this extremely long-lived cuneiform script and, in the process, to isolate the founding words from their numerous offspring. That etymological knot is relatively modern; tied in the 19th century and deserving of its own thorough investigation while the evidence is still relatively fresh. A sword might come in useful.

Fortunately, the long-lasting Greek myth of a wild bull linked to the island of Crete holds some useful clues to assist in recovering knowledge of at least one important chapter from our past. Theseus, hero of that story, possessed a thread with which to escape alive from a labyrinth, home to the dangerous Minotaur, half bull and half man.

“[Theseus] escaped the cruel bellowing and the wild [Minotauros (Minotaur)] son of Pasiphae and the coiled habitation of the crooked labyrinth.”

(Callimachus, Hymn 4 to Delos 311 ff, trans. Mair, Theoi.com)

The wording of that account from the 2nd century AD brings to mind the little-known concept of the martyr’s death inside a brazen bull (introduced in part 3), an extremely ancient theme discovered in the process of retranslating Enki’s Journey to Nibru. The ‘cruel bellowing’ is particularly significant in that the muffled shrieking of the victim, their voice transformed to sound like that of the bull, was an essential element in the torture chamber’s setup. The possibility of a complex analogy between the intestines of a butchered bull and the ‘coiled habitation’ or labyrinth of the Minotaur is also intriguing.

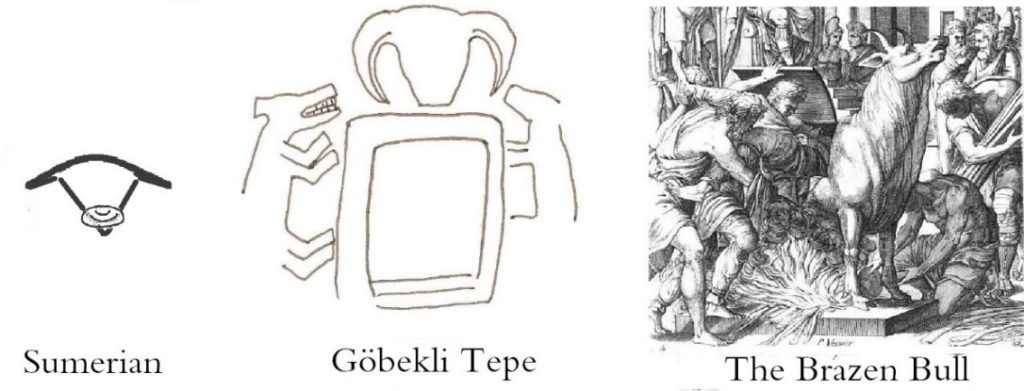

Here above on the left is the Sumerian word meaning the ‘innards of the cow or bull’, found in context as the ‘brazen bull’ in a text written ca.1600 BC. The centre image is a stone feature at Göbekli Tepe carved ca.9600 BC. It depicts a bull’s head above a framed square ‘box’. On the right is an engraving from the 16th century AD showing the lifting of a square cover on the body of the bronze bull of Phalaris and the insertion of a martyr1.

And there are others scattered around. The highest element of the stained-glass window devoted to Saint Eustache of Antioch in the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris shows him ensconced in a bull and surrounded by flames. Note that Saint Eustache and Saint Antipas of Pergamum (mentioned in part 3) are directly linked to southwest Turkey. All of these images, so distant in time, one from the other—is this just coincidence? What was it about the bull that invoked the idea of hellish fire and martyrdom? What author wrote the Greek myth of the Minotaur? Where did they get the story?

Three baskets

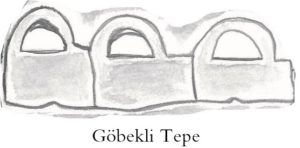

The phenomenon of the worldwide bag had already been hotly debated for some time when this enigmatic trio reappeared atop pillar 43 at Göbekli Tepe. Inevitably, their presence and great age have added an extra dose of fuel to the widespread fire. In 2017, I proposed my own solution—this one entirely justified by the words of a scribe writing in the cuneiform script of the region in which the carved image was found.

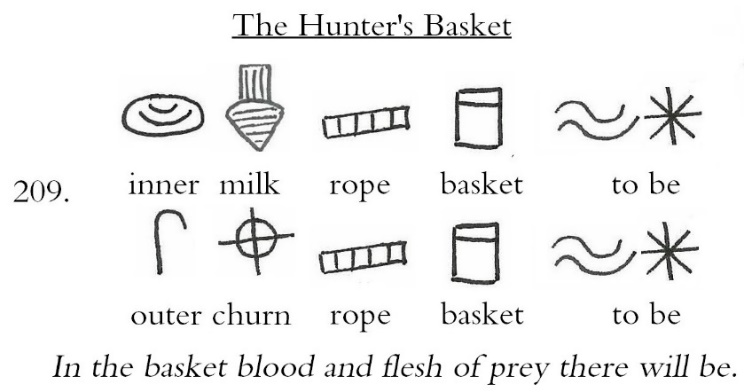

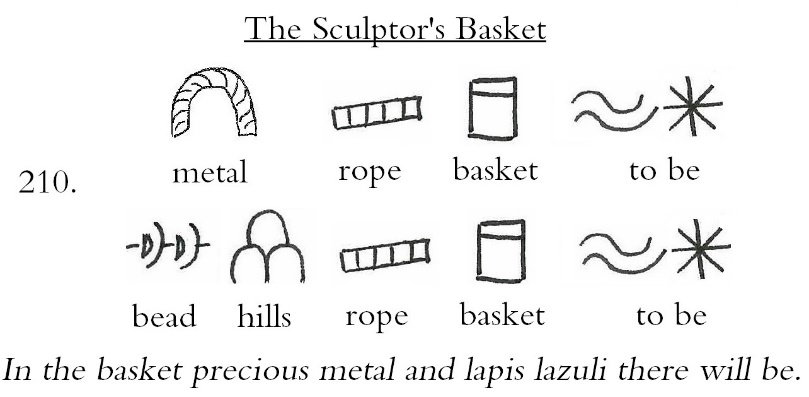

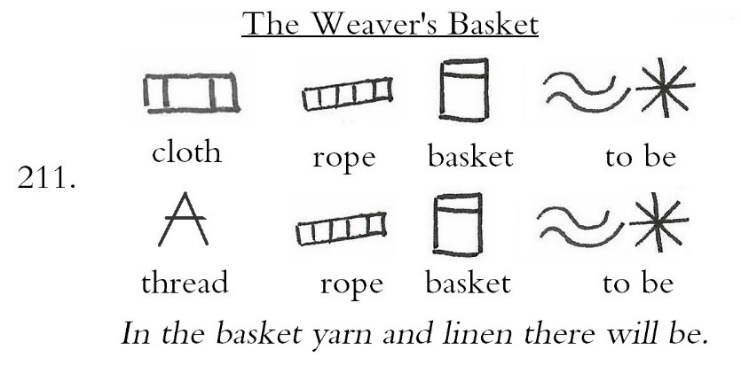

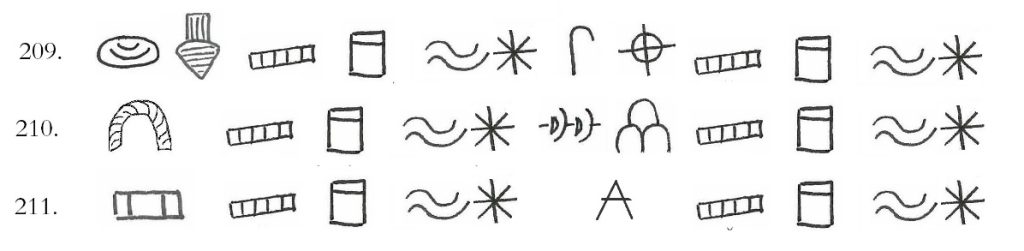

In The Story of Sukurru, (aka The Instructions of Shuruppak inscribed ca.2600 BC), and in the context of a ceremony, three consecutive lines 209, 210 and 211 between them contain six mentions of rope and basket. A three-word phrase, ending with the verb ‘to be’ (combination of two pictograms), appears twice on each line. This results in a total of three baskets along with three categories of articles: one basket of food and drink (line 209), one with precious metals and jewellery (line 210), and one with a sewing kit of cloth and thread (line 211). Here below the words taken back to their pictographic forms, and a detailed explanation:

In context, the dictionary-given ‘heart/inner’ with ‘milk’ at the beginning of line 209 were translated to the less orthodox ‘blood’. The pictogram of a shepherd’s crook, along with the churning symbol, are given in lexicons as ‘wolf’ when preceded by the word for a canine or feline. Here ‘outer’ with ‘churn’ or ‘beat’ became the ‘wild’ of an untamed animal; hence the ‘prey’. Taken together at their most superficial level of meaning, the four words of line 209 represent the first offering: that of a hunter.

However, there exists an underlying meaning where ‘inner’ and ‘milk’ (see GA in part 3) become the ‘innards of the cow’, a phrase that leads back to the pre-Greek concept of the brazen bull. The following ‘rope’ becomes the length of the cow’s intestines or, in one well-known case, that of its body (‘length’ being another orthodox meaning). This is the Mesopotamian equivalent of the great and elongated cow goddess Hathor. It’s not only Greek mythology that stems from the culture of the earliest Mesopotamians. Hathor’s body is a long tunnel through which a pre-Greek hero must pass.

Note that RA, transliteration of the word labelled ‘churn’ here above, is placed to the right of a pictogram having the shape of a shepherd’s crook. RA can also be read as ‘thresh’. The crook and flail (thresh) are symbols of the Egyptian king who carries them across his chest during his journey through the underworld. Sumerian RA is the ultimate source of the Meso-Egyptian sun god Ra. This is his story.

In the second basket, KUG is ‘metal’ and ‘pure’ in accordance with academic dictionaries. The following words, ZA, as ‘bead’, combined with KUR, the ‘hills’, together become dictionary-given ‘lapis lazuli’, a deep blue stone mined from the hills of modern-day Afghanistan. Precious metal and lapis lazuli: the offering basket of someone carving out stone or metal or both; a sculptor, a carver, a scribe.

Taking KUG as ‘rounded’ or ‘circling’ (see the pictogram) with ZA-KUR as lapis bead, the three words together become a Mesopotamian stone cylinder seal. Engraved seals provided a method of printing images and words when pressed into clay and could be worn around the neck. In the underlying theme of the baskets, this was an essential element in the Meso-Egyptian travelling kit of the king. Equivalent to the Book of the Dead, it contained the instructions to successfully navigate the underworld, or the winding intestine of the cow, or an underground labyrinth…

Also found in Maestro of a Lost World, KUG was understood in that context as a reference to a circling vessel while ZA was taken to be a sound echoing in the hills (as seen in the three mounds of pictographic KUR). The most likely source of this image of ZA is the sistrum, an instrument played loudly by the mythological Greek Kouretes after the birth of Zeus. The sistrum is well attested in the Minoan culture and was also a symbol of Egyptian Hathor.2

The third basket carries cloth and thread and is thus easily identified as the offering basket of a weaver. That said, phonetic TUG2, translated here as ‘cloth’, has a number of other possible dictionary-given meanings, including ‘cover’ and ‘understanding’. It can also be read as ‘forethought’ while GAD/KAD, transliteration of the ‘thread’, is the most essential item to have on hand when entering a maze of any kind.

Forethought was said to be the attribute of Prometheus. It is generally accepted that he takes his name from the Greek word3 and yet, in terms of the thread, it might be a better fit for Theseus. The difference between the two mythical Greek heroes is that Theseus had the forethought to equip himself with a rope while exploring a maze, while Prometheus stole the fire from Zeus and ended up tethered by cords to a high rock. Both faced great danger, but only Theseus was free to choose his course of action. Prometheus was made to suffer for his deeds and to count on outside help.

In summary, the first layer of meaning in that text from ca.2600 BC has the three baskets as offerings from three groups within the community – hunters, carvers and weavers – to a celestial matriarchal figure in the context of a winter solstice ritual. On another level of meaning, the hero of the story will embark on a dangerous journey equipped with a lapis lazuli cylinder seal carrying written instructions on how to proceed and a rope with which to find his way back out. It’s a story involving potential death and regeneration.

Three Baskets and Three Stars

One of the ways in which meaning is occulted in the Sumerian texts is through the use of acrostics, where repetition of a word, usually at the beginning or at the end of consecutive lines, indicates a coded message. In The Story of Sukurru, I belatedly became aware of a series of intertwined word games between lines 223-227 (now collectively named The Sumerian Solstice Riddle). In the case of the three baskets on lines 209-211, the final magic word is AN, the eight-pointed star:

Past and present Assyriologists, with their usual narrow focus on religion or superstition, have interpreted AN as either the name of a specific Sumerian god (Anu) or as a silent prefix before the name of their many other prefabricated gods and goddesses. Here, coupled with A, ‘water’ and ‘flow’, and appearing in the generally accepted position of a verb (at the end of the line), the composite word is transliterated AM3. Its primary meaning is given in dictionaries as the verb ‘to be’, and it is used as such throughout my translations.

In the context of astronomy, the meaning hidden in those three flowing stars is easy to find. This is the scribe’s indication that they should be read vertically and that the reference is not only to three baskets containing offerings but also to the sky. Three eight-pointed stars give the pictographic version of the word transliterated elsewhere as MUL with dictionary-given meanings ‘star’ and ‘to shine’ (repeated multiple times in the well-known Mul Apin astronomical text). In this particular context, they are the three stars of Orion’s Belt, known in other later tales as three kings or magi carrying gifts to a new-born child, fitting perfectly with the story of offering baskets here. And if they were, as later described, shepherds following a guiding star, then the coded words of line 209 become increasingly relevant. One way of reading this occulted message:

Look for three vessels carrying precious information with which to navigate and measure the skies.

My suggestion is that the three bags discovered at the summit of Pillar 43 should be understood in the same multi-layered astronomical light as the Sumerian text written in the script of that region:

On one hand, they contained the same offerings to a matriarchal figure in the context of a calendrical ritual. Presumably, the bags were physically hauled to the top of the T-shaped pillars by means of ropes or deposited there by means of a rope ladder. That ritual would have been accompanied by heartfelt prayers for the renewed fertility of the earth and of the people. The fertility theme fits with the understanding of the hill of Göbekli Tepe as a navel – one of the places on earth where an umbilical cord links us all to the celestial mother.

On the other hand, the three stars are those on the belt of the giant hunter Orion, who is linked to the sun and to the imminent rebirth of Sirius, a prominent star in the face of Canis Major – three stars in the sky and a rope for measuring distances. The stars and the verb ‘to be’ are inscribed six times. Three in the sky and three on earth. Where on earth might we look for the mirror of Orion’s Belt? 4

Is this story of the journeying hero entirely about the night sky, or is there more to it? A journey through the stomach of the beast or perhaps an existing maze? We turn again to Greek Theseus, a hero setting out to defeat a wild bull inside its labyrinthine home. Did he carry a knotted rope tied around his waist? And where did the story of a great bull coupled with a labyrinth first take shape? Was it in the Cretan city of Knossos or further east on the mainland of Asia, somewhere in the region of the Taurus Mountains of modern-day Turkey, where there exists a massive network of ancient tunnels leading to a number of underground cities?

Long before the appearance of the Ionians, a fundamental connection existed between the inhabitants of the Mediterranean islands and those on the western shores of the Asian continent, between modern-day Greece and Turkey. The entire region lived under the threat of a re-awakening of the Hellenic volcanic arc, notably on the island of Santorini. Did early inhabitants of those volatile places have the forethought to set up a mutual system of warning based on eery rumbling sounds from below, the muffled bellowing of an unseen raging bull? Did the knowledge of perpetual danger from volcanic activity in the region lead to plans for a carefully executed exodus across the sea towards the east and perhaps even to drills in preparation for such an event? Did someone in a long distant past prepare a massive underground refuge in which to house many thousands of people and to survive long-lasting climatic disasters? Who carved out the underground labyrinth of Derinkuyu in southern Turkey? When and why?

When the Hum Begins

It took some seven years to get to the bottom of Enki’s Journey to Nibru and to self-publish the only true translation of the text. Is it word-perfect? No, perhaps not, but it’s a darn sight closer to the original version than any other. At the beginning of that quest, I continued to work in my very personal style – a mix of pictograms, handwriting and illustrations – previously used for The Story of Sukurru. Then, after twenty lines or so, I got completely stuck and almost gave up.

Those few pages of Enki’s Journey stayed pinned to a wall at eye level for about three years without any significant progress. I studied them daily with growing frustration and the strong sense that someone was teasing me. That was before I had realized the extent to which the Mesopotamian scribes employed riddles. And it wasn’t until the connection with both the subject of astronomy, the Harranians and the site of Göbekli Tepe had been made (let it be said once again that this was almost entirely thanks to Magicians of the Gods) that someone somewhere relented and led me to the guiding thread. And what a solid rope that turned out to be!

The lines inscribed ca. 1600 BC – which I firmly believe to be a copy of something considerably older – had been deliberately laid out to encode important mathematical and astronomical knowledge. Although unnumbered on the clay, each line was written to fit a certain order, primarily related to the phenomenon of precession. Therein lay the lost key to the main door of that labyrinth. It was hidden in plain sight, out of the reach of all those who have not taken the time to learn the basics of astronomy – and even further beyond the grasp of all those who think themselves more learned than our Mesopotamian forefathers.

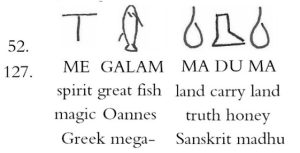

Here below, a five-word phrase discovered on lines 52 and 127, presented as it might once have been written in pictograms of the 4th millennium BC:

Line 127 of Maestro of a Lost World comprises fourteen words in all. The puzzle pieces are all still there. Oannes can be put back together and brought back to life thanks to the clever construction of the scribe. The great and up-risen Mesopotamian fish-god—well attested in both ancient images and the writings of Berossus but curiously absent from Sumerian translations5 – has been travelling across land and sea carrying his bittersweet honey of truth for far longer than anyone can fathom, just waiting to be consulted.

When the flight of a swarm is imminent, a monotonous and quite peculiar sound made by all the bees is heard for several days.

(Aristotle, The Nature of Animals, Part 40)

Once upon a time, it was well known that bees must be kept informed of everything that happens on earth. They were and still are the keepers of our secret records. They haven’t forgotten, even if we have.

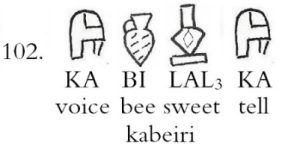

In Maestro of a Lost World, it’s the loud buzzing of the swarm, gathered into a dark swirling cloud, that will tell the truth of the path of the bull at night. (The ‘path of the bull’ in that text was translated from the word JIR3 – see part 3). The sound of bees is mentioned on lines 92 and 102, with the most eloquent warning of imminent catastrophe on line 93 (see my article The Comet Strike).

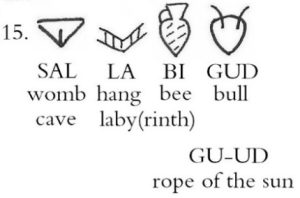

Here below, a few more words, this time borrowed from line 15 of Maestro of a Lost World:

Is this the death-inducing nectar of the Pontic Mountain honeybees that Oannes carries in his bag? Is this the origin of the bittersweet scroll offered as food by an angel in Revelation? What a strange verse that is! Is there still hope, or is it too late to cut through an age-old accumulation of falsehoods and honest mistakes to get to the truth?

The warp threads of an ancient matrix were deliberately severed at more than one point in time over the thousands of years that separate us from the creators of Göbekli Tepe. The written stories from our common past have been ripped up and reconstructed more than once, re-woven with ever larger, increasingly tangled knots, all leading down blind and senseless alleyways, diverting our eyes and minds from the truth. But as it turns out, thanks to the skill and forethought of an ancient nameless astronomer-scribe, the original rope was designed to never fail. All we had to do was see it for what it is and then pull. There has always been hope.

Notes and References

1 Phalaris condemning the sculptor Perillus to the Bronze Bull, after Baldassare Peruzzi, by Pierre Woeiriot de Bouzey (1532–1596?).

3The name is Greek, and anciently was interpreted etymologically as “forethinker, foreseer,” from promēthēs “thinking before,” from pro “before” (see pro-) + *mēthos, related to mathein “to learn” (from an enlargement of PIE root *men- (1) “to think”). In another view this is folk-etymology, and Watkins suggests the second element is possibly from a base meaning “to steal,” also found in Sanskrit mathnati “he steals.” (Etymonline.com)

Prometheus’ name stems from Sumerian transliterated PIR, the ‘sun’ and its fire (also UD) along with UM-ME-TE, the ‘cord of measurement’ (see UM-ME-TE in perfect context in The Story of Sukurru, line 68). This is consistent with the notion of forethought. The hero remembers to carry a cord for safety. The new-born child entering the world is safely attached at the navel to the umbilical cord. More generally, the measurement of space and time necessitates a cord. The final US in Prometheus stems from the Sumerian word ‘male’ carried forward into Greek as a suffix in male names.

4 The newly translated text of Enki’s Journey to Nibru comprises a couple of paradigm-shattering deviations from the region of Ancient Mesopotamia; one takes us to the Giza plateau and the other to Cusco in Peru. The tools with which to analyse and to fully understand these encoded messages existed in the literature of the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC.

5 To my knowledge, there are no other clearcut cases – involving some logical context – of the upright fish-god in the translated Sumerian texts. He is known only from ancient Mesopotamian images and later mentioned in Greek as Oannes. That said, a link can be made with the so-called Anunnaki and Apkallu. It involves the word AP/AB with the meaning ‘sea’ and the NUN of Anunnaki (also indirectly linking to Apkallu) with the meaning ‘guide’.

- The Labyrinth and the Travelling Bag: Part 4 of Images from Göbekli Tepe and Other Neolithic sites reflected in Sumerian pictograms and texts

- Land of Milk and Psychedelic Honey: Part 3 of Images from Göbekli Tepe and Other Neolithic sites reflected in Sumerian pictograms and texts

- Images from Göbekli Tepe and Other Neolithic sites reflected in Sumerian pictograms and texts – Part 2. Pagan Wings and Sailors’ Feet

- Images from Göbekli Tepe and other Neolithic sites reflected in Sumerian pictograms and texts – Part 1. The Pillar and the Snake

Its not a bag, its weights with its all meanings. (used to compare weight of goods and also spiritual meaning weight of soul)…. in one of pictures are even traders with these weights and other with goods – 13:13

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c9i__vrDwd4

Sixteen minutes of repetitive word salad mingled with an unhealthy dose of modals ‘could have, would have, may have, might’, along with a few sneaky insertions of totally unjustified affirmations. The image you cite is a specific scene showing people carrying goods in various containers. Nothing surprising that bags or baskets served that purpose in everyday life.

Of particular interest: “The handbags often resemble modern purses and totes, items that did not exist thousand of years ago.” Who would have thunk it? An old bag that looks like a new bag!

Note that they use Graham’s name in the title, no doubt to gain traction for their site.

Largely uninformative drivel. And yet it has half a million views already. Oh well…

Nah