Gilgamesh, Mesopotamian hero of heroes. That’s the name – or something close – that popped up in a Greek text titled On the Nature of Animals, written by Claudius Aelianus in the 2nd century AD. It was written ‘Gilgamos’, but why quibble about one vowel sound in one syllable? Another author, Theodore Bar Konai, writing in Aramaic around the 8th century, mentioned a certain Gligmos in a list of kings, again an approximation which sounds reasonable and serves, as far as I’m concerned, as confirmation that the trouble with Gilgamesh began well before the modern era.

In Lost Stones Of The Anunnaki, I made the case that all the well-known translations of the Mesopotamian tablets, whether labelled as Sumerian or Akkadian, are seriously flawed in more than one way, the most obvious fault being the profusion of invented names; those names serving to conceal an unfortunate lack of understanding of the subjects of the texts. But what of Gilgamesh in all this, the most popular and profoundly Mesopotamian figure of all? What is his place in this version of history? He’s not a modern invention. Of that we can be sure thanks to those second-hand accounts from antiquity.

But perhaps the early authors were simply repeating a name they had heard and not seen – or seen already copied into their own later languages. They would be the first in an ever-increasing number of people taking it at face value. There is no way of knowing if they had access to far earlier sources of information on the subject of Gilgamesh. But today we certainly do. We have a plethora of sources that go directly back to the Mesopotamian world in which he first appeared.

Apart from his appearance on numerous tablets, of which those carrying the famous Epic of Gilgamesh, the name is mentioned twice in the modern-day translations of the post-diluvian Sumerian King List, taken directly from those tablets with strictly no intermediary – apart from the transliterator (from cuneiform script to alphabetic) and then the translator of course. So what did the original tablets on which the name has been found multiple times actually say? What words were used? And does it matter? I think it does. Words matter. Etymology matters. Truth always matters. What were they really writing about? Should we have blind faith in the information handed to us on this and other ‘Sumerian’ matters by self-proclaimed experts from the 19th and 20th centuries, information that has cemented itself as irrevocable truth through constant repetition? Or should we be less trusting and make the effort of looking at the source material – largely available today on the internet – for ourselves and without the help of either transliterator or translator? Straight from the horse’s mouth, so to speak?

Graham Hancock, in Magicians Of The Gods, points to the possibility that the Mesopotamians were aware of the precessional cycle of 25,920 years known as the Great Year and makes the case that the astronomers who carved Pillar 43 at Gobekli Tepe ca.9600 BCE were directly referencing that complex celestial phenomenon. Thanks to the clarity of Graham’s account and in light of my recent findings, I’m considering the possibility that not only did they know but that it was one of the subjects of their far later texts. With that in mind, I also turned to another fascinating book titled Hamlet’s Mill¹, which is well known to those who take an interest in ancient knowledge of astronomy. The overall ambition of its two authors, Giorgio de Santillana and Hertha Von Dechend, is to demonstrate that ‘all myths have a common origin in a celestial cosmology’. They are particularly scathing when it comes to the quality and reliability of existing accounts of all things Sumerian. More than once, they intimate that blind faith might not be such a good idea. For example (and it is just one of numerous comments of the type), they write about Samuel Kramer, a renowned Assyriologist (1897-1990):

But one cannot expect earnest thoughts to be wasted on Sumerian conceptions from a scholar who wrote about the fathers of hydraulic engineering (irrigation) that “to the Sumerian poet and priests the real sources of the Tigris and Euphrates in the mountains of Armenia were of little significance …(…)” (Hamlet’s Mill, p.438)

My own thought is that any ‘Sumerologist’ (I have come to dislike that newly minted name: Sumer) who sings the praises of or refuses to acknowledge the obvious, proven and shocking errors in the translation of the most ancient literary text of them all – The Instructions Of Shuruppak (aka The Story Of Sukurru) – has, at best, touched on nothing more than the first superficial layer of the language. In order to begin to understand the mindset of that civilisation, respect is a pre-requisite, followed by a minimum of knowledge of the subjects on which they might be writing. From my translations, it has become clear:

- that the Mesopotamian texts involve the use of riddles, notably acrostics, in at least two of the longer texts (a number of ‘proverbs’ are retranslated on my website: https://madeleinedaines.com/ ),

- they refer to rituals involving mind-altering substances,

- they provide the source material for Ancient Greek mythology and for the heroes of Homer’s tales,

- they provide the source material for sections of the Bible,

- and that they are steeped in references to cosmology, a complex subject that I am beginning to perceive in my ongoing translating efforts.

Unfortunately for the authors of Hamlet’s Mill, in compiling their study of comparative mythologies, they had only the officialised translations of the Sumerian texts to work with. Consequently, their book (which I have read at least three times now in order to fully grasp its significance) could do nothing more than helplessly repeat the multi-syllabic meaningless names of Sumerian gods and heroes, attempting to match their stories to that of the celestial mill – and to the complex astronomical phenomenon of precession. Trying to make sense of it all by comparisons with other equally mistranslated texts, as they do at certain points, amounts to a snake biting its own tail: circular and pointless. They write in the annexe:

…we do not like those ‘beyond all doubt’s,” and similar verdicts, considering how frightfully little we know of the Epic (If there is something that is really “beyond all doubt” it is only this, that the eleven tablets of the Epic do not “constitute a reasonably well-integrated poetic unit,” not the translated Epic.) (Hamlet’s Mill p.442)

In that regard, at least, I have more strings to my bow and wouldn’t dream of using the phrase ‘beyond all doubt’ unless I had something serious with which to back it up. Not having met him in The Story Of Sukurru, I went looking elsewhere for the truth about Gilgamesh.

Metamorphosis

In the beginning was the Word. In the case of Gilgamesh it was six words, or five, or four or just two. It all depends on which tablet you read. For those who have no direct knowledge of the language, forced to rely entirely on people who claim that they do: Know that he is made up of more than those three syllables: Gil-ga-mesh. Once again, the monosyllabic method of investigation takes us to his very essence, and we can at last meet him in the flesh, so to speak. But first:

Among the crowd came the cypress, formed like the cone-shaped meta, that marks the turning point in the race-course: once a boy, but now a tree: loved by the god who tunes the lyre, and strings the bow.

(Ovid, Metamorphoses, Bk. 10 The Death of Cyparissus, Trans. A.S. Kline)

And what better wood for the musician’s lyre or for a great archer’s bow than that of the majestic cypress tree which, according to Ovid, was much loved by Orpheus, master of music and of sleep, manipulator of men and stones, the eternal trickster?

Proceeding thence, she learnt by inquiry that the chest had been washed up by the sea at a place called Byblus, and that the surf had gently laid it under an Erica tree. This Erica, a most lovely plant, growing up very large in a very short time had enfolded, embraced, and concealed the coffer within itself. The king of the place being astonished at the size of the plant and having cut away the clump that concealed the coffer from sight, set the latter up as a pillar to support his roof.

(Plutarch, Moralia, On Isis and Osiris, Trans. C.W. King)

Cypress or erica or any other species, Ovid’s Cyparissus, Mesopotamia’s Gilgamesh and Egypt’s Osiris are all three intimately linked to trees; those that, after being cut down and drifting many miles along a mighty river, serve to prop up the roof of a great king’s temple or are carved into instruments of enchanting, sleep-inducing music or otherwise shaped into a mighty bow from which to propel the mightiest of arrows; both lyre and archer’s bow fittingly stringed.

The trouble with Gilgamesh is that he can be found in more than one text, but the only two words that remain constant throughout, in every mention of it, have been obscured by modern scribes. They are quite simply never pronounced, rarely even mentioned in the side-notes. Worry not…listen to the lyre of the fox until your head nods…watch the celestial arrow soar over your head…or read on.

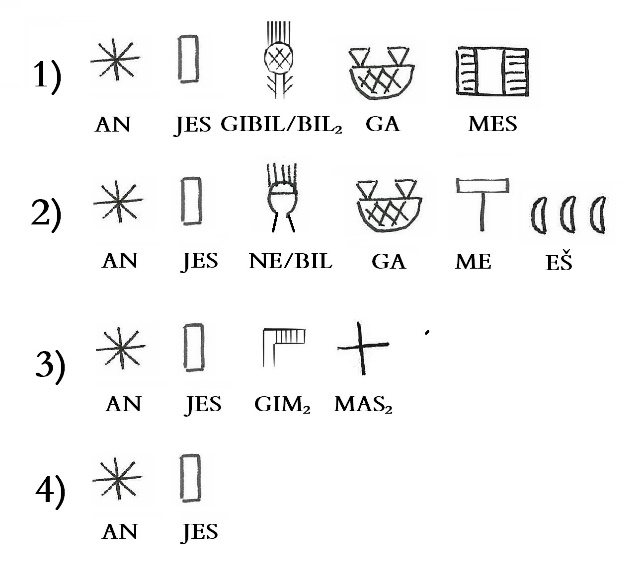

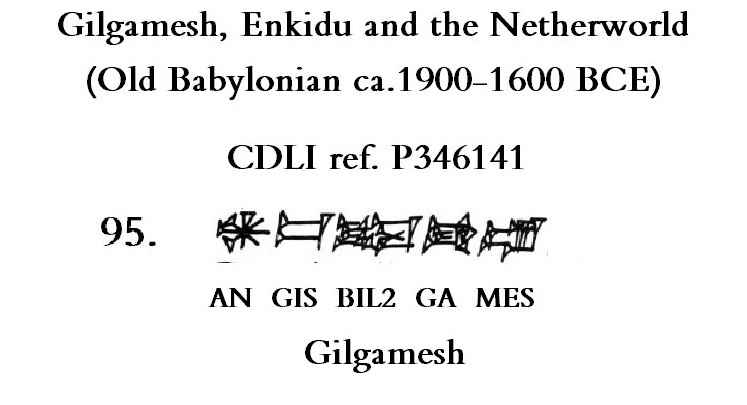

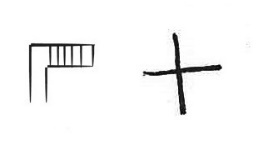

Below is the most complete list of the source words and variations compiled from published transliterations of the Epic of Gilgamesh and other documents. As usual, I have peeled them all back to the pictographic forms in which they might once have appeared in the 4th millennia BC. (The Old Babylonian tablets of ca.1900-1600 BC show them in the far later and better known abstract cuneiform):

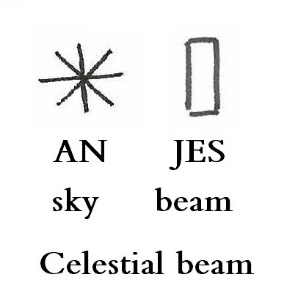

There is something truly bizarre about Gilgamesh when you see him for the first time in this Mesopotamian light. Some element that appears to be conspicuously absent from the received pronunciation of his name. It’s plain to see that only two words are constant throughout all four versions; AN, the sky, and JES/GIS/GIZ, the tree or wooden beam, which, in a monosyllabic language, would give ‘celestial tree’, ‘celestial beam’, potentially even ‘roof beam’ if AN, looking up at it, is seen as a roof. When we read Gil-ga-mesh, that prefix is missing. Both words have been passed over, silently erased. Worse still. On the version of the Epic of Gilgamesh known as the Pennsylvania tablet, Gilgamesh doesn’t exist at all beyond those two words. The entirety of that tablet has no other name than AN-JES – I’ve looked – and yet there again, it’s translated to Gilgamesh.

Strangely, in the course of another supposedly unrelated literary text where AN JES appear just once, there is no sign of Gilgamesh at all. The two words on that tablet don’t cause a stir. They don’t have Sumerologists jumping around, tearing at their clothes and shouting, ‘Eureka! I’ve found Gilgamesh!’ No, the words are left unmentioned. They lie at the beginning of line 139, which comes at the end of the following passage. Maybe you can find them. I certainly can’t:

Today let my penis be praised, may your wisdom be confirmed (?)! May the enkum and ninkum …… proclaim your glory ……. My sister, the heroic strength ……. The song …… the writing (?) ……. The gods who heard …… let Umul build (?) my house …….”

(Enki and Ninmah, ETCSL ref.1.1.2)

You might read the above and assume that the dots and question marks indicate breakages in the original tablet. They don’t and it’s not. The text is intact.

Strange to think that only two words have been steadfastly ignored throughout the long history of Gilgamesh. In the case of AN, I can tell you why. The symbol of the eight-pointed star is ignored because, at least in our time, it’s taken to mean a ‘god’ and is therefore a silent prefix, indicated by a small ‘d’, sentenced to forever float, aimlessly and invisibly in front of a meaningless name. Look no further.

My own translation of AN, also given in the dictionaries as ‘sky’, usefully extends it to the adjective ‘celestial’ and mentions it as such when it appears. Words which have overly religious connotations in today’s world are, for the most part, kept out of my translations. I’m not completely sure of the beliefs that held sway some five thousand years ago or the way in which they would have been expressed. Neither do I subscribe to the received wisdom that the texts were the reflections of priests and/or poets. There can be no wild guessing passed off as fact. A good dose of humility is a prerequisite for travelling Mesopotamian skies. Of that, I have been well and truly informed.

That AN was not an integral and pronounced element of the name appears to be an assumption first made, at least in this case, long before the 19th and 20th century translators got stuck in. The notion that it might be otherwise important, that it might have something to do with astronomy, with stars, planets and real celestial events, appears to have passed most people by completely.

As for the silent JES, there is no logical reason for ignoring either the tree or the wood in his name unless, of course, Gilgamesh was somehow considered to be wooden in the same way as the handle of an agricultural tool. In which case, it might just have been seen as a second silent prefix: a wooden god or perhaps the ‘god of trees’ who just happens to be Gilgamesh, so no need to mention it too directly. The authors of Hamlet’s Mill came close in that they were sure something was mightily wrong with the Epic. As they so witheringly put it:

The epics of Gilgamesh and Era offer too many trees for our modest demands. The several wooden individuals have, however, the one advantage that the expert’s delight in uttering deep words about “the world tree” wilts away. (Hamlet’s Mill p.437)

The only explanation appears to be that JES was deemed untranslatable in that position. To my mind, the multiple mentions of the word for ‘tree’ and indeed the text in its entirety were so impenetrable for the translators that they could not fit this one into any slot at all and had no choice but to ignore it altogether – or, heaven forbid, admit their ignorance. Perhaps the thought process went something like this:

“Well, if Aelianus, a 2nd century Roman, wrote that this was pronounced Gilgamos, then who am I to quibble?”

And yet AN with JES are the only two constants among all the tablets and fragments of tablets thought to refer directly to a character called Gilgamesh. How can that be? There has been some scholarly debate on the subject with regard to the Pennsylvania tablet, but nothing useful has come of it.

The Fire

The third element of the name on the first two examples, GIBIL (also written BIL2) or NE, are two words from the same source pictogram, a drawing based on a palm tree, seen here on a tablet fragment² from the Uruk IV period, ca. 3350-3200 BC. This example is GIBIL, the entirety of the tree with its frond bursting upwards from its crown, seen as a metaphor for fire and/or firewood which are its given meanings. NE, the other version, is the crown and frond of the tree without its trunk. Both are given as related to fire and burning, and apparently interchangeable when it comes to Gilgamesh’s name. Nowhere is the palm tree itself mentioned as a possible meaning. I have extended the fire of NE to include ‘new’ with notions of birth and rebirth from the ashes, that of the eternal phoenix.

When the word AN is used directly before GIBIL (omitting JES) on some unrelated tablets, any fleeting thought of a similarity to our hero’s name is again brushed aside and those two together become plain Gibil, Sumerian god of fire, neatly worked into translations under that guise.

In some versions of the Enûma Eliš Gibil is said to maintain the sharp point of weapons, have broad wisdom, and that his mind is “so vast that all the gods, all of them, cannot fathom it”. (Wikipedia, quoting from Michael Jordan, Encyclopedia of Gods, Kyle Cathie Limited, 2002)

As far as I can tell, it’s not only the gods who are unable to fathom it.

The Holy Cow

The fourth word in the name on the first two examples given above is GA, the milk of the celestial cow carried down to Earth from her many udders, apparently in a woven basket. GA is source of Gaia, Mother Earth, and an element of GAN, womb, crucible and Milky Way. It’s also given at a late date with the meaning ‘carry’. One possible translation of GIBIL followed by GA might be: ‘the fire carried (in the basket/vessel)’, but it would depend on the all-important context. Here a version of GA from the 4th millennia³:

One of the themes developed by the original scribes was the use of mind-altering substances. Inasmuch as they had a sense of humour, used metaphorical language and indulged in riddles, it’s very possible that some bottles of Mesopotamian milk had more unusual properties than we find in the stuff on supermarket shelves today.

More on GA in that regard: https://grahamhancock.com/dainesm5/

The King List

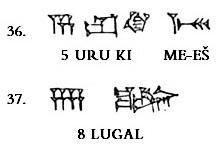

On the Sumerian King List transliterations (lines 112 and 117), Gilgamesh appears to be written in both versions (1) and (2) above: AN-JES-BIL2-GA-MES or ending ME-ESH. However, at least on the version in the Ashmolean Library, that’s not the case. Both lines are transliterated – and presumably originally written – as MES.

ME-EŠ, which I translated to the ‘three magicians’ and tentatively to ‘three ships’ in Lost Stones, does appear at an earlier stage on the antediluvian portion of the list. They’re written on line 36. The flood comes just a couple of lines later.

There is nothing in the academic translation to indicate their presence on that line of text in which the total of the pre-flood cities was given. Just a couple of the many words that fell through a 19th century trapdoor. As for their presence underlying the far later mention of Gilgamesh on any fragment of the King List, I have to take the experts’ word for it because I failed to find it. However, that form of his name does exist according to the ePSD website and can be found there by typing Gilgamec2 (Gilgamesz2 on CDLI).

MES is given as ‘darkness’, ‘seal’ and ‘hero’ in the dictionaries, this last being most probably a result of its appearance within the Gilgamesh phrase – a good example of a snake biting its own tail. But it might also result from the fact that this is the MES of the original Magician, Her-mes (Lost Stones p.73). MES is closely linked to ME-EŠ as their alphabetic forms (based on the cuneiform lexical entries) suggest, but they are not the same words. MES appears to be based on DUB, the writing tablet, with the addition of striations suggesting there is something important written on it. So again, potentially three magicians linked to a written tablet. Here below the full name of Gilgamesh, copied from a tablet written in the later abstract cuneiform:

The Double Axe and Crown

He was the cleaver of the earth, who was represented by the cleaver as an axe which, we take it, was a sign of Horus, the cleaver of the way. The god of the double equinox who completed the course from horizon to horizon was Horus of the double force, which doubled force was variously imaged by the double crown, the double uraei, the double feather, the two lions, the two crocodiles, and other dual types. Hence the god himself is called “the double Harmachis.” He was cleaver of the way, whose double power was likewise imaged by the two-headed weapon which has been termed the “divine double axe” of the Mycenaean cult.

(Gerald Massey, Ancient Egypt, Light of the World, Vol.1, The Sign Language of Astronomical Mythology, p.341)

Horus with Double Crown at Temple of Edfu, © Ad Meskens / Wikimedia Commons

The third rendering of Gilgamesh on the above list gives GIM2-MASH, the original pictograms translating very smoothly – again using dictionary-given meanings – to both ‘double axe’ and ‘double crown’. Given the existence of a double link, perhaps this version of the name should first be considered in relation to the above intriguing quote and surrounding text in Massey’s Ancient Egypt.

Considered in the light of JES, the tree, and his alternative epithet of GIBIL, the firewood, the utility of a double axe in a rustic setting is not in doubt. But what does it mean? With apologies to both priests and poets, I prefer to look to the well-attested master astronomers of Mesopotamia, and to their concept of a celestial mill – transliterated HOR/HUR/HAR or MOR/MUR in the language of that region – and to find in this version of the name something more subtle and infinitely more interesting than a man cutting down trees in a cedar forest.

In Lost Stones Of The Anunnaki, I delved quite deeply into the JES tree, discovering the source of both Jesus and Osiris hiding inside. It was more than the cross on which Jesus was crucified or the roof beam of a king’s palace. It was the name itself. Not only that. The beam was the mast of the celestial ship to which Homer’s Odysseus was bound while enticing music played, and it was the great dill stalk in which Greek Prometheus stored the stolen fire. (In my retranslation of The Instructions Of Shuruppak, I came across both Odysseus and Prometheus with their original names.) The rope of time is mightily knotted but not broken. Horus of the churning mill is never far away.

And therein lies the essence of the meaning behind Mesopotamian Gilgamesh. The celestial beam holds all of them in place, from top to bottom, from bottom to top, from beginning to end and back again. All roped together. Of course, there is far more to the story, more than a short article can encapsulate and, I daresay, far more than I have yet perceived. At this point in my ongoing investigations and translations, my main goal has become to offer a substantiated answer to the following question: Did the Mesopotamians – more precisely the earliest Sabians of Harran – have knowledge of that complex and extremely long cycle of time known as precession whereby the sun is perceived as travelling in an anti-clockwise direction through the constellations? As I said, Graham Hancock in Magicians Of The Gods strongly suggests that they did. I would not be at all surprised.

Metamorphosis: “change of form or structure, action or process of changing in form,” originally especially by witchcraft, from Latin metamorphosis, from Greek metamorphōsis “a transforming, a transformation,” from metamorphoun “to transform, to be transfigured,” from meta, here indicating “change” (see meta-) + morphē “shape, form,” a word of uncertain etymology. (Etymonline)

Meta- word-forming element of Greek origin meaning 1. “after, behind; among, between,” 2. “changed, altered,” 3. “higher, beyond;” from Greek meta (prep.) “in the midst of; in common with; by means of; between; in pursuit or quest of; after, next after, behind,” in compounds most often meaning “change” of place, condition, etc. This is from PIE me- “in the middle” (Etymonline)

morph-, word-forming element of Greek origin meaning “form, shape,” from Greek morphē “form, shape; beauty, outward appearance,” a word of uncertain etymology. (Etymonline)

JES/GIZ: Latin gest: “famous deed, exploit,” more commonly “story of great deeds, tale of adventure,” c. 1300, from Old French geste, jeste “action, exploit, romance, history” (of celebrated people or actions), from Medieval Latin gesta “actions, exploits, deeds, achievements,” noun use of neuter plural of Latin gestus, past participle of gerere “to carry on, wage, perform,” (…) from PIE root (Etymonline)

References:

¹Giorgio de Santillana & Hertha Von Dechend, Hamlet’s Mill, 1977, David R. Godine, Publisher.

²Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI) ref.P001167, Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin, Germany.

³CDLI ref.P001332, Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin, Germany.

Neith has been speculated by some scholars, such as J. Gwyn Griffiths and Jan Assmann, to be the actual goddess depicted in the first and second century Greek historian Plutarch’s description of the Veil of Isis in his On Isis and Osiris. The veiled Isis is a motif which associates her with mystery and ceremonial magic. Plutarch described the statue of a seated and veiled goddess in the Egyptian city of Sais. He identified the goddess as “Athena, whom [the Egyptians] consider to be Isis.” However, Sais was the cult center of the goddess Neith, whom the Greeks compared to their goddess Athena, and could have been the goddess that Plutarch spoke of. More than 300 years after Plutarch, the Neoplatonist philosopher Proclus wrote of the same statue in Book I of his Commentaries on Plato’s “Timaeus”. In this version, a statement is added: “The fruit of my womb was the sun”, which could further be associated with Neith, due to her being the mother of the Sun god Ra.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neith

Yeshua or Y’shua (ישוע; with vowel pointing Hebrew: יֵשׁוּעַ, romanized: Yēšūaʿ) was a common alternative form of the name Yehoshua (Hebrew: יְהוֹשֻׁעַ, romanized: Yəhōšūaʿ, lit. ’Joshua’) in later books of the Hebrew Bible and among Jews of the Second Temple period. The name corresponds to the Greek spelling Iesous (Ἰησοῦς), from which, through the Latin IESVS/Iesus, comes the English spelling Jesus.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yeshua

Josh, Do either have these messages have any direct bearing on my article about Gilgamesh? As far as I can tell, you only post quotes here on a regular basis, sometimes extremely lengthy and not obviously relevant to the subject in hand. You don’t add an enlightening comment so that we can know what it was you had in mind. But perhaps I’m being unfair and missed some where you do…? I note that you have begun adding the links – always a good idea. As for the etymology of Jesus, I daresay most people could find it for themselves if they’re interested.

Madeleine, yes they do.

Fine. In that case, please explain your reason(s) for posting them in relation to my article. Thank you.

I will not be providing any information to you which you are not able to understand in the first place. I have offered this information for others who understand its relevance without explanation.

“Because it is given unto you to know the mysteries of the kingdom of heaven, but to them it is not given.

12 For whosoever hath, to him shall be given, and he shall have more abundance: but whosoever hath not, from him shall be taken away even that he hath.

13 Therefore speak I to them in parables: because they seeing see not; and hearing they hear not, neither do they understand.

14 And in them is fulfilled the prophecy of Esaias, which saith, By hearing ye shall hear, and shall not understand; and seeing ye shall see, and shall not perceive:

15 For this people’s heart is waxed gross, and their ears are dull of hearing, and their eyes they have closed; lest at any time they should see with their eyes, and hear with their ears, and should understand with their heart, and should be converted, and I should heal them.

16 But blessed are your eyes, for they see: and your ears, for they hear.

17 For verily I say unto you, That many prophets and righteous men have desired to see those things which ye see, and have not seen them; and to hear those things which ye hear, and have not heard them.

15 He that hath ears to hear, let him hear.

16 But whereunto shall I liken this generation? It is like unto children sitting in the markets, and calling unto their fellows,

17 And saying, We have piped unto you, and ye have not danced; we have mourned unto you, and ye have not lamented.

18 For John came neither eating nor drinking, and they say, He hath a devil.

19 The Son of man came eating and drinking, and they say, Behold a man gluttonous, and a winebibber, a friend of publicans and sinners. But wisdom is justified of her children.”

There can be little doubt that anyone reading this your first real message (?) on Graham’s site – those two lines at the top of yet another unreferenced bible quote – will have understood exactly what I had already noted: that most if not all of your posts here have little or nothing at all to do with the articles in question.

There really is no need for you to provide this sort of information without a personal comment to explain your reasons. I doubt very much that readers other than the authors themselves spend any time at all trying to work out your motivations. And most people can navigate Wikipedia and Biblehub (wonderful site) for themselves.

Best not to feed the trolls, love.

Do I appear to be in need of advice on how to interpret and respond to messages, sweety pie? If you feel the urge to add yet another layer to this already pointless exchange, your own status will be duly noted (i.e. not worthy of a response). Josh C. or Craig P. same difference – nothing of any interest added in the comments to my article.

Havent you heard? Feeding Trolls is the Law.

Have a nice day, friend.

Unfortunately it’s fairly common for these religious nutcases to spam comment sections with unrelated material. I’m glad to see your research, thanks.

Josh / Craig,

If you read the article (and the nine others posted on Graham’s site), you will see that the message involves the need to be careful of the words we choose; clarity and truthfulness, respect and humility being prerequisites for translators. I pointed to those words that had been ignored, dropped in modern times from the Mesopotamian translations that we have in hand; I also pointed to those words that have been added, invented in recent times out of the original writings.

Your usual posts on the Articles board make you out to possess unusual or occult knowledge unavailable to the average human being – nod, nod, wink, wink. I know that they are not directed at me in particular because you do it to almost every author here. However, most people – even if they take an interest in those writings copied and pasted – will lose all interest when they realise your absence of any relevant thoughts or information. That’s life. I was simply pointing that out – your posts, cloaked in fake mysticism, being the antithesis of the article they followed in this case.

Then, the more recent posts are designed to provoke: Strike up a conversation on the side-lines, suggest that my attitude is authoritarian towards your ‘friend’, have the last word and shame me into silence. C’est raté, as the French say. And almost funny if we take it to mean that Craig is calling Josh a troll… who is consoling ‘friend’ Craig for my treatment of him… Molière would be in awe!

All of this might be of interest in terms of psychoanalysis – but that’s not why I’m bothering. I’m bothering because you posted twice directly under my article on Gilgamesh and, in so doing, intentionally linked your words/quotes to mine. I’m bothering because it’s actually quite a good demonstration of the importance of understanding the power of words and how their meanings have been and can be manipulated – until we take a closer look. And yes, I’m still willing to read and to react to the thoughts that might yet accompany your quotes – if there are any.

Madeleine:

If you read my original comments, you would clearly notice their relevance to specific claims of your article. If you cannot grasp such blatantly obvious facts in a clear and simple way, it indicates something quite definite about your intent and intentions.

A person does not necessarily need to specifically say something like “You are stupid” to another person in order to betray the idea as an unspoken thought or assumption within their psyche. There are plenty of other specifically spoken things which will indicate this thought by proxy, by motivation, by passive-aggressive beating around the bush, and so forth. Therefore it is useless to argue with people who claim things like “I never said that” while they are quietly thinking it and therefore basing their actions upon such thoughts. The fact that it is not said in a specific way is beside the point. Passive-aggression is still aggression. Anyone who tries to pass it off as “peaceful cooperation” is either a liar and/or an unconscious tool of other manipulators.

Propaganda is as old as language itself. It serves a definite and specific purpose.

Have a nice day, friends.

First off, you made no ‘original’ comments. That’s the whole point of this exchange, Josh. I’ll make it clearer for you: there were no comments. There were only quotes taken from external contexts. You are confusing commenting with quoting.

Secondly, your implication – particularly through unreferenced quotes – voids discussion; that much is true. It can also be extremely rude – by implication – and needs to be called out in certain circumstances. That’s why I have bothered with you, Josh. On social media and in a more general setting I would happily ignore you. I have published my translations and very clearly stated my intentions here and elsewhere. No-one needs your help in that regard. But now we are at least all crystal clear as to your own decidedly unpleasant thought processes.

Finally (and this is final as far as I’m concerned) and since you mention it, propaganda is another evil linguistic device, a deliberate underhand distortion of truth which presents itself as fact – while offering no referenced, verifiable evidence – and should always be called out for what it is with the greatest clarity possible – I’m pretty sure that our host here would agree wholeheartedly with that.

I was referring to the two comments in which you asked “do these messages have any direct bearing on my article”. This is clearly shown above. It is an obvious reference. Again, just as in your refusal to acknowledge what I have said in the two comments above, you can continue to do this all day long, forever, with anything I have to say. You can keep moving the targets endlessly. You can reframe, reboot, reinterpret, redo, reform, etc. etc. any word to be any definition you wish in your own private conceptual world, and then you can use your own privately defined words to construct any sort of subjective fantasy you wish – but that has nothing to do with actual objective truth such as 1 + 1 = 2. The actual consensus reality which is shared by all lifeforms has no basis in conceptual languages composed of any words of any sort whatsoever. Subjectivity is not objectivity. Physical reality is based purely on physical facts and objective truth, which by its very nature cannot be completely described, only symbolically referenced, and even its actual functioning is only approximated by pure mathematics.

You can choose to ignore my comments for whatever “reasons” you wish. That is your choice. However, the result is still nothing more than you ignoring what I have to say – and it is not based on anything more lofty than your own personal excuses for your own ignorance on the matter. You dont have to address my comments, just as I dont have to address yours. I do not need to explain myself to you. Neither of us are required to explain ourselves to anyone. This information may be useless to you, and that is fine with me. As I said in my earlier comments: “I have offered this information for others who understand its relevance without explanation.”

It is not exclusive to Sumerology it is the case with Indology. Where they purposely twist and invent the meanings of Indian texts to suit their agenda. It is like they dont want people to know the truth.

I mean it is the same case with Indology too.

Interesting. How do you believe the original texts have been twisted? How do you know about this?