Remain in Me, and I in you. Just as a branch is unable to produce fruit by itself unless it remains on the vine, so neither can you unless you remain in Me. (John 15:4)

If you remain in Me and My words remain in you,

ask whatever you wish, and it will be done for you. (John 15:7)¹

Shifting Sands

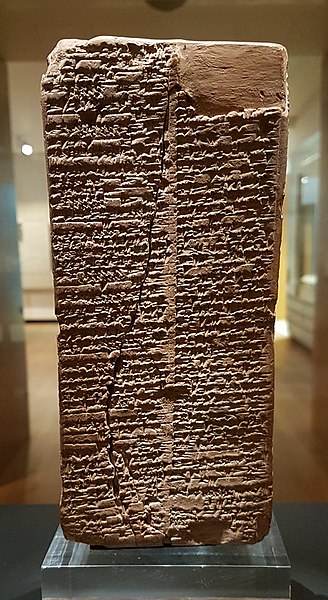

The various rediscovered tablets and fragments of the antediluvian Sumerian King List, along with mentions in other texts, give two or more possibilities for the name of the final king before the flood. In his detailed study and comparison of those artefacts, Thorkild Jacobsen, (1904-1993) an esteemed Assyriologist and Sumerian translator, came to the conclusion that the primary name, i.e. that which he considered to be the most ancient and therefore most relevant overall, was UBAR(A).²

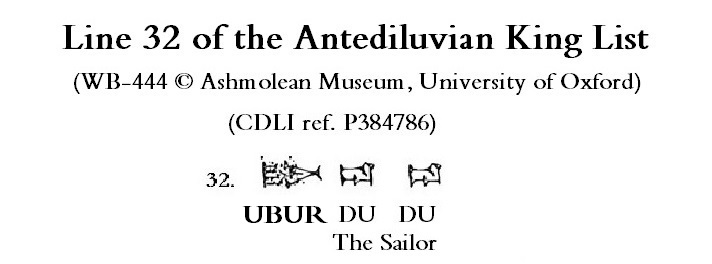

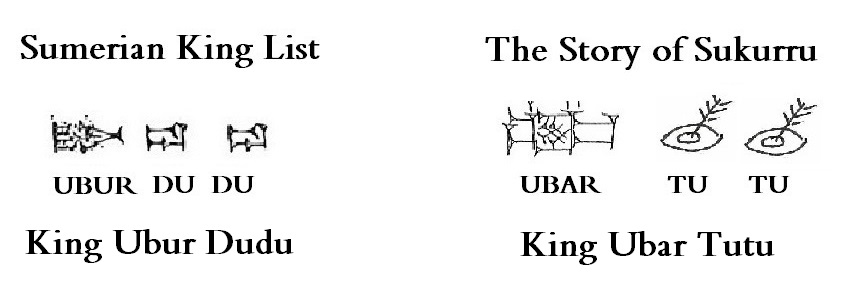

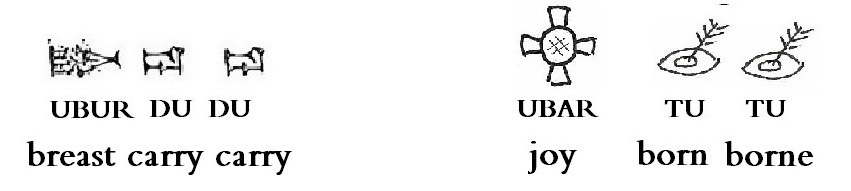

There should be no wiggle room at the stages between tablet, transcript and transliteration. To write Ubar when the visible word is Ubur is to make a personal choice based on a broader picture, one which does not conform to the scribe’s intent. Whether that scribe was copying from an older tablet or not, whether they had failing eyesight or not, their words must be copied into alphabetic form by modern-day scholars to exactly reflect the original text. It’s already little short of a miracle that we have the possibility to read the thoughts of people from as long ago as 2600 BC. It can’t be assumed that they had any intention other than that which appears before us. That said, I can’t pretend that I haven’t been guilty of the crime of lèse-majesté, going against and thus insulting the Mesopotamian sovereign. In The Story of Sukurru, my own version used UBARA DU DU whereas the transliteration stated UBARA TU TU.

Apparently, the learned Assyriologists at the University of Oxford agree with that principle and the phonetic form of the Sumerian king’s name given on the (no doubt already relatively old) transliteration appearing next to the prism has now (as of October 30th, 2021) been changed to the original word intended by the master scribe: UBUR.

Unfortunately for me – and despite my pleasure in having assisted in the recovery of that name associated with an important artefact – this poses a new problem. I had previously posited two other words, LIL or SUHUR, to repair the error, both of which are at some point in time visually very close to UBUR. Either LIL, the fool, or SUHUR, the carp, give reasonably comprehensible epithets fitting quite neatly into my overall assessment of the figure. On the other hand, UBUR’s main given meanings are ‘breasts’ and ‘nipples’ with an underlying theme of ‘milk’.

The King’s Nipple

Clearly, the most obvious translation of Ubur to Great King Nipple doesn’t sound so good! And so I set off in search of UBUR’s deeper meanings and had to rewrite a paragraph or two before the publication of Lost Stones Of The Anunnaki. Sumerian is like a lively fish. You think you’ve got it hooked but no – it’s off again.

According to the now copious corpus of Mesopotamian tablets displayed on the CDLI website, the word UBUR appears 156 times on a total of 119 tablets or other artefacts. Its earliest appearances date to the Early Dynastic period (ca.2500-2340 BC) where it figures 18 times, most often in inscriptions on stone bowls or vases, The fact that the Sumerian UBUR existed in 2500 BC proves that it was not, as Assyriologist Thorkild Jacobsen appears to have posited in his seminal work, a late development out of the word UBAR. They had always been two distinct words and had existed side by side for at least five hundred years before the Ashmolean prism was inscribed. In fact, UBUR figures on another well-known Mesopotamian artefact. It’s listed in the wording of the famous Stele of the Vultures, the fragments of which date to around 2500 BC and are currently housed in the Louvre. That stele is far from complete but some of the images and, no doubt, part of the inscription are understood to be mythological.

To summarise: From the various fragments of the Sumerian King List and from various other sources, which include The Instructions of Shuruppak/The Story of Sukurru, we find that the last king before the flood had two epithets: Ubur Dudu and Ubar Tutu, to which we can add a third from a fragment which mixes them together, giving Ubur Tu Tu:

The strong phonetic similarity between them doesn’t mean that they are interchangeable at will. Only a Mesopotamian scribe could enlighten us about their choice of symbol, and we have none on hand. One thing is sure. The cuneiform words and their meanings are explorable and that is an exciting aspect of the figure. We have two distinct pieces of information about the king of Sukurru/Shuruppak who is said to have reigned there for 18,600 years. They are not the same, but they are most certainly related in some way.

Once A Fish Always A Fish

Ubur-ubur has the meaning ‘jellyfish’ in Malay. This is not the first time I come across an astonishing link, one that goes beyond a quasi-perfect phonetic match, between Sumerian and Malay, and it serves here to bring the subject back to first base.³ At the outset of this investigation, I suggested that the symbol now identified as UBUR by academia was possibly SUHUR, the carp. In truth, its outline, closely similar if not identical to that of SUHUR, seems to indicate that it was indeed meant to visually portray a fish. Not a jellyfish, of course. No, a regular everyday fish – perhaps more than that, one that has the magical ability to rise up through swirling waters against all odds; the carp when it swims and jumps against strong currents in its Homeric effort to sail to higher spawning grounds…homeward bound. That upward swimming fish is attested on Sumerian seals. The jellyfish has a different method. It puffs its way up from the depths of the ocean, sometimes luminescent, sometimes immortal, always stunning – like a lung pumping unseen winds to propel itself forward.

As an aside, the French word ‘poulpe’, one name for the octopus or cuttlefish, stems from Greek polys meaning ‘many’ or ‘much’, a feature of such creatures being their multiple tentacles or possibly a plurality of feet (?). Our word ‘pulmonary’, adjective relating to the lungs, stems from Latin pulmo. Both, I suggest, originate in Sumerian BUL/PUL which has the given meanings ‘to blow’, ‘to rock’, ‘to shake’ and ‘to inflate’. Both are given as being ‘from Proto-Indo-European’, i.e. an unknown source.

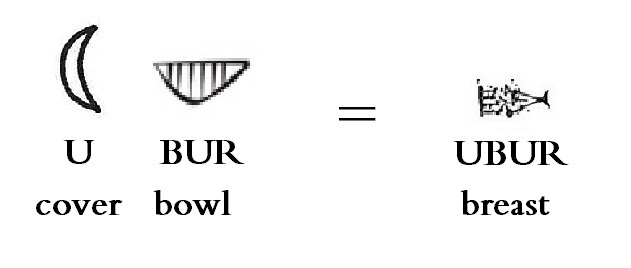

Of course, a Malaysian ubur-ubur does not a Sumerian jellyfish make per se. A quick glance at those ever-useful Sumero-Akkadian etymologies known as the ‘lexical lists’ brings up the possibility of finding a monosyllabic origin to UBUR: one result is U, the ‘cover’, with BUR, the ‘bowl’. That meaning plays into the fact that the word UBUR is found primarily on stone bowls and other vessels at the earliest period of its known existence.

Now imagine trying to describe the shape of a jellyfish’s body: an upside-down bowl or its matching cover? Add into the mix that UBUR, the word, has a shape similar to that of other words given to various fish. The tail fin is still apparent even at this stage in the evolution of the Mesopotamian language. There can be no absolute proof that this was the original intention but still… a linguistic and visual mix of different sea creatures. Why not? Was UBUR once the name given to a jellyfish and perhaps others having similar features: an octopus for example, or an ink-squirting squid? Is that why it was also used for ‘breast’, ‘nipple’ and ‘milk’? A stretch perhaps. And so I will move on. But first, one last comment: an upside-down bowl bears a certain resemblance to a jellyfish which bears a certain similarity to the average mushroom cap. Do they all bear a certain resemblance to a plump breast and even to a softly sloping hill? Surely not. Here below the moon jellyfish for comparison:

‘Aurelia aurita’ by Andreas Augstein (CCBY3.0)

Onwards And Down/Upwards

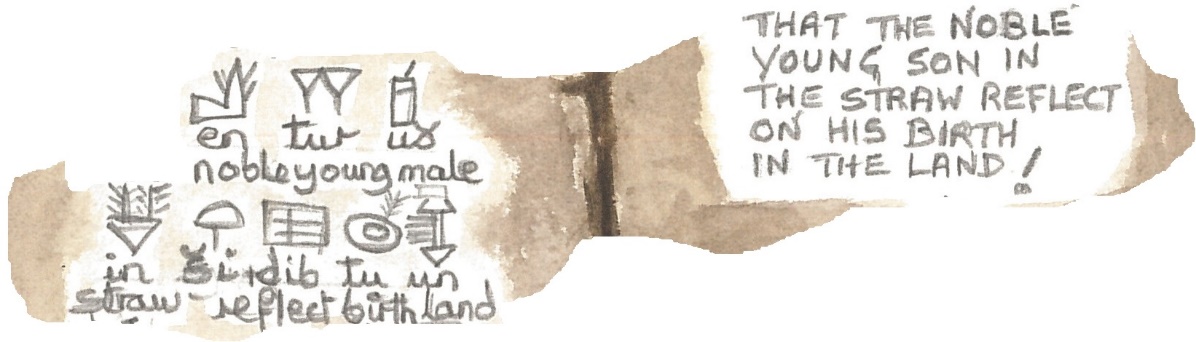

DU and TU are two different words. Nevertheless, they have a concept in common. They are both concerned with the act of carrying. DU, the foot symbol, has the given meaning ‘to carry’ which is logical for a pair of feet, while TU, its pictographic version being a curious mix of what appears to be an egg yolk pierced by a feathered arrow, has the given meaning ‘to bear’. The difference between them is that TU is directly concerned with the womb as a carrier. TU refers to the foetus borne in and born from the womb. This is the word translated to ‘birth’ a couple of times in The Story of Sukurru. In that story, two children, a boy and a girl, are carried off from their ship by the Bird of Knowledge and left to reflect on their birth (TU) inside her nest of straw, along the Milky Way. Line 247 ends:

One Sumerian word for youthfulness is TUR which takes the form of a pair of downward pointing breasts in some pictograms, presumably a reference to breastfeeding and a signal that this is a very small male child, as yet unweaned.⁴ But then the question has to be asked: Considering that this study relates to the name of a great king on the antediluvian King List, why would he be portrayed with a double epithet of birth or even pre-birth? One possible answer is that the figure, who obviously has two feet and might well be both a sailor and a fish, was understood to have been twice-born, borne in the womb of a great Matriarch, fed with milk from her breast, and resuscitated or saved in some way, rendered as immortal as some species of jellyfish perhaps.

The Sumerian story is seemingly never-ending; there is always more to be found. But this is a mere article and must be rounded off at some reasonable point. UBAR is a complex symbol with an array of underlying themes, which include a direct link to the source name Hermes. For now, I will end with one of its dictionary-given meanings: joy.

While the lefthand name conforms to the cuneiform style of ca.2000 BC, the righthand version has been peeled back to the visual forms that Ubara Tutu might have taken if he had existed during the earliest pictographic era five thousand years ago. If he had existed…⁵ Born-Again King of Joy! Now there’s a fitting title, positively glorious!

References

¹ See ME ZU NU MU ZU: In ME there is no self. (ETCSL Proverbs from Nibru, Coll.6.2.1. Trans. M.Daines) https://madeleinedaines.com/

² Thorkild Jacobsen, The Sumerian King List, 1939

https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.283790

³ ‘Ukur’ which is Malay for ‘to measure, ascertain the quantity of a unit’, appears in the eleventh proverb on my website which translates to ‘Avoid dangerous greed’. Also, Malay ‘agar-agar’ on p.166 of Lost Stones Of The Anunnaki.

⁴ TUR with UŠ, the young son, found on line 247 of The Story of Sukurru, also appears in the lexical list cited at the end of AMA-NITA Mon Amour:

https://grahamhancock.com/dainesm5/

⁵ The word can be found as far back as 3200-3350 BC, but without its central element and written as EZEN, the ‘festival’ and ‘song’. It’s even found there in the company of SUHUR, the carp (CDLI ref.P002553). A thoroughly fishy, upward, and joyful word. The transfiguration of Jesus comes to mind and also the word ‘metamorphosis’. In ME there is no self. ME ZU NU MU ZU. Around and around we go.