Since the 19th century, when many thousands of clay tablets rather suddenly appeared out of ancient Mesopotamia, a great deal has been written about the Sumerian language. This is the earliest writing system known to the modern world, its script having evolved stylistically from the pictographic forms of the 4th millennium BC to the short abstract strokes of the Akkadian cuneiform during the 3rd millennium BC. Cuneiform was still in limited use as late as 100 AD.

Between the original text in a defunct language and its translation into something comprehensible in a modern world lies the process of transliteration, the transformation of unfamiliar scripts into other more easily recognizable visual forms. In the case of both Sumerian cuneiform and hieroglyphic Egyptian, all knowledge of which had been lost by the 19th century, the process began with the discovery of multilingual inscriptions, one of which was in a known language and served to decipher the other.

As things stand today, the alphabetic equivalences of the original Sumerian pictograms and subsequent Akkadian cuneiform have taken on far more importance for scholars than the original words of the scribes. Little thought is given to the tiny abstract signs once they have been transliterated and none at all to their source pictograms in the process of translation. Each word appearing on a clay tablet has been rebaptised with several different – sometimes numerous – alphabetic forms, each supposedly indicating a different meaning. These are then sifted, chosen or left to one side entirely according to the translator’s largely preconceived convictions as to the intention of the scribe, both in terms of grammar and subject matter. Primitive superstitions are more easily conjured up than references to astronomy, about which the translator might know little or nothing. Relatively straightforward accounts of regal splendour override more obscure and subtle references to the importance of spirituality and truthfulness. Stories of rituals involving shamanic initiation, including the use of mind-altering substances, become invisible through a lack of knowledge of such subjects. Ignorance builds on ignorance. Great numbers of meaningless names of gods or other figures have been created out of the modern ether to fill the gaps. And certainly, no thought is given to the eventual presence of an ancient riddle to be understood through the positioning and repetition of certain words.

Forced through the meat-grinder of a dominating, unimaginative mindset and presented to the general public as if written in stone, the most ancient texts in the world have been quite easily reworked and moulded to suit the expected narrative. Who’s to know? Who’s the expert? Presenting the Sumerian pictograms as little more than crude references to trade, that largely false narrative negates all possibility of joining the dots between the people who created Göbekli Tepe and the authors of the clay tablets found in and around ancient Mesopotamia. It will continue to hold sway until the true picture of the civilization that generated those Mesopotamian scribes seeps through the inevitable cracks. In the meantime, only the odd sparkle of some authentic gem remains visible under the rubble.

a) The T-shaped Pillar

It is also true to say that a great deal has already been written concerning Göbekli Tepe in the comparatively short time since that most famous of the neolithic sites in southeastern Turkey was first uncovered in the late 20th century. The distinctive forms of the monolithic T-shaped pillars, along with the carvings and other artefacts found in or around those places, have naturally led to considerable speculation as to their meaning and purpose, but they have yet to be considered in the light of the earliest known language of that place.

The age gap between the archaeological sites and the appearance of the first written words – approximately 5 to 6,000 years (ca.9600 BC to ca. 3500 BC) – might well be seen as an impediment to recovering knowledge of the ancient world through a study of pictographic Sumerian. However, given the large number of similarly shaped stones shown to have existed in the region, it is quite easily proven that the gap did not involve an absence of knowledge of their existence or some element of their function. Images of similar pillars continued to appear, notably in Anatolia, until well into the 2nd millennium BC.

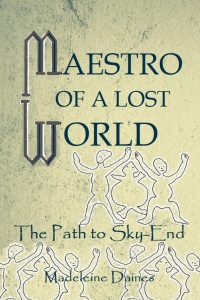

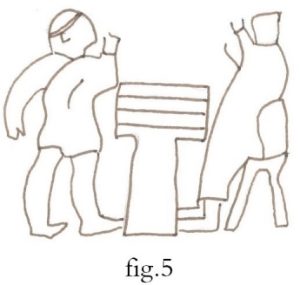

The above pillar (fig.1), wound around with cords or strips of cloth, appears on a wall of the Hittite Sphinx Temple at Alaca Höyük. It also figures more than once on vases from a Hittite source ca. 1600 BC (see fig.5). Inasmuch as the writing system (a variation of Akkadian cuneiform) of that culture is not well attested, little solid information can be gained from it. Fortunately, the Sumerian pictograms, around two thousand years older, also contained signs of enduring links to the people who carved the pillars of Göbekli Tepe.

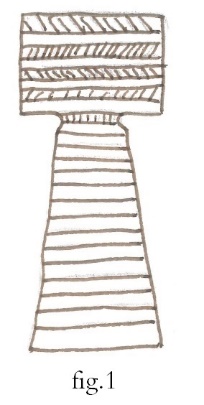

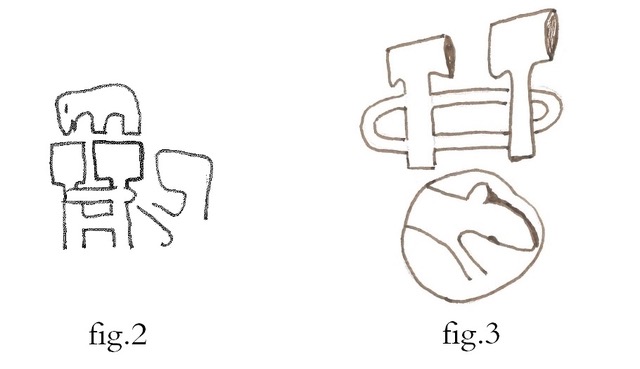

For example, abstract depictions of the round stone enclosures featuring two central pillars (such as those of enclosures C or D at Göbekli Tepe) were once imprinted onto hollow balls of clay known as ‘bulla’ (fig.2). Bullas contained any number of small clay tokens and are thought to have been used for trading. They are given as pre-writing, noted as somewhere between 8500 to 3500 BC. (Presumably, Assyriologists don’t seriously consider it likely that they were in use so early.) The same unmistakable imprint appears again on several tablets more safely dated to the Uruk IV period, ca.3350 to 3200 BC (fig.3).

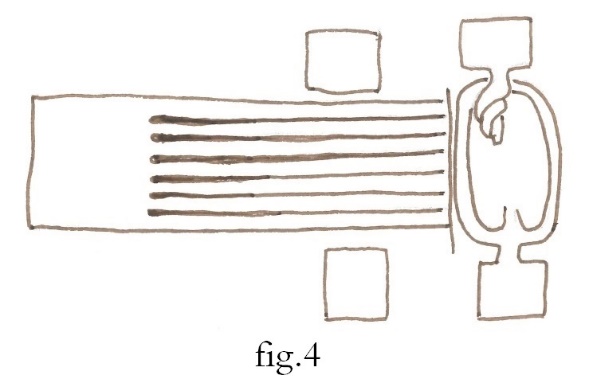

The above image from around the same time (fig.4) shows the two pillars as elements of some unknown weaving apparatus. The scene on the tablet from which it was copied is partially erased, making exact reproduction difficult. Nevertheless, it is definitely a weaving scene. The three or four surrounding human figures have been left out of this sketch. Note the distorted perspective; a semi-ariel view with the pillars laid out flat and another pair protruding on either side of the warp threads that stretch out between them – seven strands of equal length in the process of being woven into a block of fabric on the lefthand side. On another bulla (not shown here), the warp threads are replaced by a pair of intertwined snakes, also stretching out to the left of two T-shaped pillars, this time with no sign of any fabric or weavers. So it appears that cords – more precisely, the warp threads, matrix of the cloth – and weaving snakes were analogous at some point in time and in some precise context.

This theme of woven cords also fits extremely well with those seen to be stretched tightly around the far later T-pillar in the Alaca Höyuk mural (fig.1). However, the human figure there, scarcely taller than the stone, holds up his hand as if in praise or perhaps to measure its height. He does not appear to be a weaver. Confirmation that this scene carved onto the wall of the Hittite temple is not a simple weaving scene is found to the right of that pillar where a majestic bull in regalia stands on a pedestal, facing towards the man. It appears to be the subject of his raised hand – perhaps a prophesizing animal.

In another Hittite scene (Hüseyindede vase), a slightly smaller pillar with similar stripes across its upper surface appears to serve as a tall table around which two figures, one standing and one sitting, are gesticulating, perhaps drinking, perhaps not. That image also detracts from the notion of the T-shaped pillars shown in Sumerian clay as a straightforward weaving instrument. In the bulla image (fig.2), a small four-legged creature is visible standing above a pillar, again providing evidence that the theme is complex.

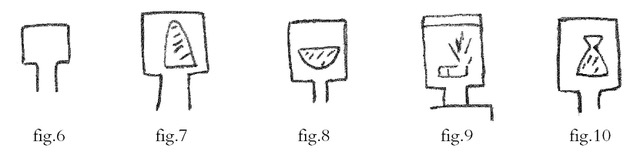

Turning now to the earliest Sumerian script, neither the alphabetic equivalence nor the meaning of the word shown here below on five different tablets from the 4th millennium (referenced as ZATU737) has been identified. However, on most of the examples, the sign incorporates other words. Here we see transliterated pyramidal SU/ZU (fig.7) ‘to know’ or ‘to learn’, BUR/POR (fig.8), the ‘bowl’, EN (fig.9), meaning ‘lord’, UNU (fig.10) ‘earth’ or ‘grave’:

Other transliterations and meanings apply according to context. For example, UNU appears just once as the second word on line 97 of Enki’s Journey to Nibru (retranslated as The Path to Sky-End) in the context of tilting caused by a great catastrophe. Its counterpart, AB, meaning ‘father’ and ‘sea’ (the same pictogram minus striations), takes fourth position on that line.

The unnamed word is the obvious choice to represent an existing T-shaped pillar in the process of creating a pictographic writing system. It is also quite obviously related to the equally unnamed T-shaped images on other clay artefacts (figures 2 and 3 here above) from around the same time or earlier. It can be said that the pillars of 9600 BC and the Sumerian word of ca.3350 BC are linked both by their form and in that they incorporate images across their surfaces.

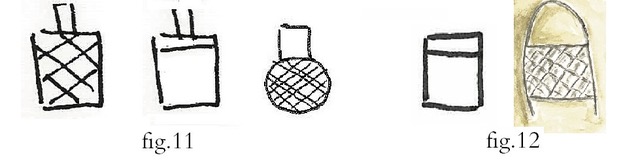

Here below (fig.11) are three versions of the Sumerian word with the meaning ‘tablet’ or ‘cylinder seal’ (among others) and transliterated to DUB (among other transliterations). On the right are two versions of MAL, the ‘basket’ (fig.12), also appearing on tablets from the 4th millennium and often incorporating other words at its heart (see AMA, celestial Matriarch: https://grahamhancock.com/dainesm5/).

Sumerian DUB is arguably the closest fit to the pictogram ZATU737, differing primarily in its orientation. Its ‘shaft’ is situated at the summit, and this element is generally closed off by a horizontal line. DUB also appears with crisscrossing striations, presumably indicating writing and/or images. The central example (fig.11) is the most closely similar to fig.9 in that it has a corresponding horizontal striation. This version is also given in some accounts as transliterated UM with the meaning ‘rope’ (among others). And in some cases, minus the shaft, it bears a strong resemblance to MAL.

The shaft is a rather surprising aspect of pictographic DUB in that it is absent in reality from all of those artefacts, the clay tablets and stone cylinder seals. There is the possibility that the pictogram represents some long-lost—because considerably less durable—wood-based writing material. Another possibility is that the rectangular appendage represents the now absent wooden shaft inserted into the central hole seen on a few small early tablets, and on cylinder seals or clay prisms (later four or six-sided artefacts). For example, the four-sided King List tablet in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, England, is pierced through from end to end. But that then begs the question of why it would not have been shown to protrude on both sides of DUB. It should be noted that the second version of the ‘basket’ (fig.12) appears to have been made of woven reeds and was copied from a remarkably well-engraved small clay tablet. Also pierced through from end to end, perhaps it served as a weaving weight.

b) Snakes, Ropes and Rivers

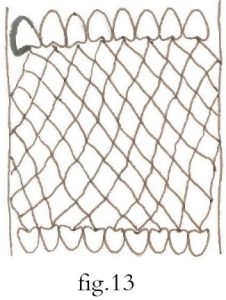

The analogy of snakes and warp threads found on the tablets (see fig.4) is also at play on the pillars of Göbekli Tepe and is particularly evident in this serpent-headed net carved across the façade of pillar 1 in Enclosure A (fig.13).

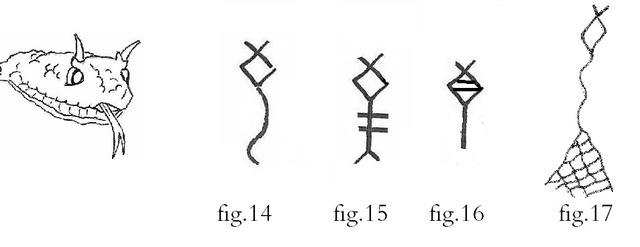

Three Sumerian pictograms, respectively transliterated BU/PU, MUŠ and SUD/SIR, are variations on an abstract rendering of the horned viper, a common and harmless snake of the region:

BU or PU (fig.14) is given as ‘long’, ‘to survey’, ‘to measure out a field’ in orthodox dictionaries but not as ‘snake’. That meaning has been applied only to its sibling MUŠ (fig.15), a word which, according to the lexical tablets, further breaks down to MU, the ‘movement’ with UŠ, the ‘phallus’, becoming (always according to context) ‘movement of the phallus’ or alternatively ‘the age of man’. Fig.17 shows BU rising out of DU₆, given as ‘mound’, a collocation found more than once.

BU can be read as SIR₂, partial source of Latin serpens, the ‘serpent’. SUD (fig.16) has the given meanings ‘distant’, ‘remote’ and ‘long-lasting’. SUD can also be read as SIR while MUŠ, the ‘snake’, can be read as ŠER₁₀.

Greek potamos, ‘river’, an element of the name Mesopotamia, takes its first syllable from transliterated PU, also the name of the Italian river Po. The Po is said to be linked to the constellation and mythical celestial river Eridanus, in turn related to Sumerian NUN/ERIDU, name of the first city on the Sumerian King List. NUN is also the central word in the phrase that became ‘Anunnaki’.

Mesopotamian snakes and rivers (or any water channels) were analogous at some point in time. An excellent example of that is visible at Karahan Tepe, a site as old as Göbekli Tepe, where a winding water channel between two pits appears to represent the body of a snake while the pit containing eleven stone pillars takes the form of its head. The snake is also represented circling around the rim of the deepest pit there. (See Andrew Collins, ‘Karahan Tepe—Its Three Interconnected, Rock-cut Structures Examined’)

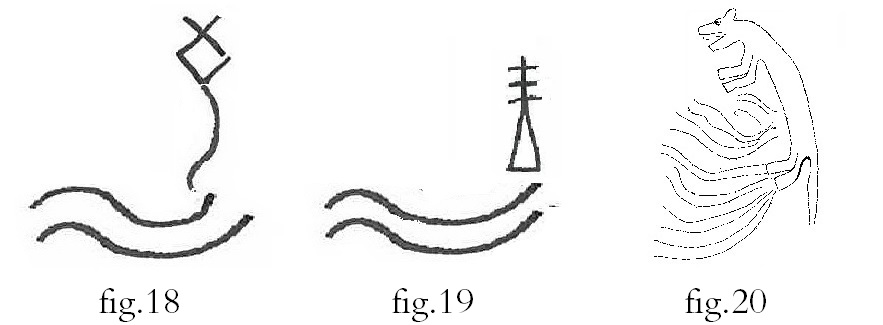

A combination of BU over A, given as ‘water’ (fig.18), appears on more than one tablet, as does the combination of NUN/ERIDU over A (fig.19). At the same time, the two parallel, sinuous lines of pictographic A, which indicate flowing movement of both river and snake, can be usefully compared to the wavy lines emanating from this jumping canine at Göbekli Tepe (fig.20). Those lines end in a series of snakeheads. Thus, it might be that the rivers represented by snakes were also warp threads on the machine of some great celestial weaver, the common attribute of all three being sinuous, constantly flowing movement.

Moving further forward in time and changing location, it becomes interesting to consider a potential link between ancient snakes and/or threads woven around stone with the well-attested and mysterious cone-shaped baetylus or omphalos stones such as that of Delphi in ancient Greece. Omphalos has the meaning ‘navel’ in Greek as does the ‘gobek’ of Göbekli in Turkish.

The Hittite images of T-shaped pillars wound around with ropes and/or strips of cloth (figures 1 and 5) and the serpent net of Göbekli Tepe (fig.13) might also be considered in relation to the interwoven snakes forming the skirt of the Aztec goddess Coatlicue or to the Celtic ‘clootie wells’ where strips of cloth (Scottish ‘clootie’) are tied around the trunks and branches of trees in proximity to a sacred well. It appears that this age-old tradition has always had healing as its purpose. Then again, two snakes winding around a rod were symbols of Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine. Finally, there is the mysterious ouroboros symbol, a snake biting its own tail, known to us through ancient Egyptian and far later alchemical documents.

In all of the above, stretching from the age of Göbekli Tepe all the way down through to Ancient Greece, there exists the strong sense of sacred binding; stone pillars bound with cords and snakes, rods or branches of trees bound with cloth or snakes.

The most obvious Sumerian words to set against such images are A, the flow, with BU, the snake (fig.18). Bearing in mind that we have no idea of the ultimate sources of the words inherited from Greek or Latin, my suggestion is that A with BU together give the origin of Greek apo-, prefix to such words as ‘apocryphal’ and ‘apocalypse’:

Greek apo “from, away from; after; in descent from,” in compounds, “asunder, off; finishing, completing; back again,” of time, “after,” of origin, “sprung from, descended from; because of,” from PIE root.

Late Latin apocrypha (scripta), from neuter plural of apocryphus “secret, not approved for public reading,” from Greek apokryphos “hidden; obscure, hard to understand,” thus “(books) of unknown authorship. (sourced from Etymonline)

Latin crypta and Greek kryphos became the ‘crypt’, a secret place as mentioned in Luke 11:33. Here in a purely spiritual context:

The men of Nineveh will stand at the judgment with this generation and condemn it; for they repented at the preaching of Jonah, and now One greater than Jonah is here. No one lights a lamp and puts it in a cellar or under a basket. Instead, he sets it on a stand, so those who enter can see the light. Your eye is the lamp of your body. When your eyes are good, your whole body also is full of light. But when they are bad, your body is full of darkness.… (Luke 11:32-34)

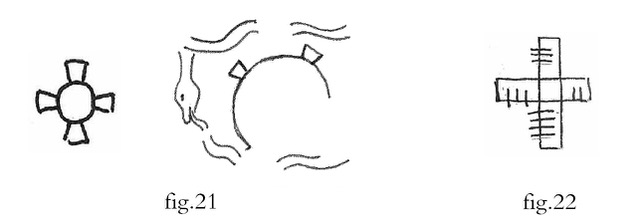

Sumerian EZEN here below (fig.21), also transliterated SIR₃ (see BU/ SIR₂, SUD/SIR and MUŠ/ŠER₁₀ above), takes slightly varying forms but mostly is a circle with small rectangular or triangular blocks around it. It is also read as HER and KIRIS (Before Babel, p.197). EZEN carries the dictionary-given meanings ‘bind’, ‘festival’ and ‘sing’, connecting it to celebrations or rituals of some type. On this damaged tablet from the 4th millennium BC, EZEN is encircled by what appears to be a number of snake bodies having a birdlike head which is biting its own (or another snake’s) tail. Figure 22, the cross, appears to be another version of the same word or closely linked, this time with striations presumably showing the binding:

Given the large number of snakes at Göbekli Tepe and other sites, perhaps the most pertinent so far discovered in relation to the Sumerian language is the snake that winds around the rim of the pit at Karahan Tepe. Both of the images, one from ca.9600 BC and the other ca.3350 BC, indicate use of the ouroboros tail-biting symbolism prior to its appearance in ancient Egyptian imagery.

All of the above does little more than scratch the surface of some almighty founding story or stories dating back to at least the 10th millennium BC. Fortunately, there are a number of carvings of other creatures and other features discovered at those Neolithic sites that can also be interpreted and reconnected to later cultures thanks to the first known words of the Sumerian scribes.

- Images from Göbekli Tepe and other Neolithic sites reflected in Sumerian pictograms and texts – Part 1. The Pillar and the Snake

- Images from Göbekli Tepe and Other Neolithic sites reflected in Sumerian pictograms and texts – Part 2. Pagan Wings and Sailors’ Feet

- Land of Milk and Psychedelic Honey: Part 3 of Images from Göbekli Tepe and Other Neolithic sites reflected in Sumerian pictograms and texts

- The Labyrinth and the Travelling Bag: Part 4 of Images from Göbekli Tepe and Other Neolithic sites reflected in Sumerian pictograms and texts

Similar patterns from the top of the pillar of fig 1 and from fig 13 can also be found in the extraordinary Colombian eight mile rock art wall.

A conjecture maybe but this Colombian site seems to contain many symbols found worldwide. And since among the vast number of figures represented there’s many that strongly resemble the ones described by plasma physicist Anthony Peratt in his 2003 revolutionary paper, it might not be that far fetched to assume that indeed all those extraordinary figures were seen in the skies around the world.

Evidently the Colombian site being likely much closer to the real aspect of what was seen while the Turkish sites were obviously a later stylized representation, trying maybe to make sense of it while also incorporating elements of their surroundings which were not directly related to those initial events.

Also, and maybe a tad far fetched, but a possible explanation to why many of those figures seen in Colombia, and on many sites around the world, have a striking resemblance to living things might be that the same assumed electrical phenomena that shaped those figures on a macro level is the same process that shapes biological structures on a micro level, as we know that electricity is highly scalable.

Madeleine, I find your work astonishingly lucid and insightful. There is a poetic depth to it that resonates strongly in spite of my ignorance of the details of the subjects of which you treat. I am finding myself going back to your earlier articles to try to catch more glimpses of what you are showing us.

Have you managed to speak directly with Irving Finkel about it? He is of course a “mainstream” guy but I get the impression he is nonetheless reasonable and charming and wise about his subject. For once.

I would love to see or hear or read a live conversation session between you two (whether involving hallucinogenic or intoxicating substances or otherwise). Perhaps you could be his trip-sitter and we could all watch? Or just have a sober conversation if he isn’t psychadelic yet?

I am sure many others would too. The most interesting insights of all can come from the bringing together of independently brilliant thinkers like this in a friendly way. Not that your work “needs” it at all – it stands alone quite powerfully by itself. But it also deserves proper attention from open-minded folk who are adept at the field who could appreciate it more fully than your average reader. Please keep it coming and get your own show!

(In the old world, everyone had a show!)

Any serious public discussion I might have on the subject of the Mesopotamian scribes would necessarily involve mention of their knowledge of the precession of the equinoxes ca.1900 BC (or far earlier) and of their shamanic initiation ceremonies. I suspect that Dr Finkel would recoil in horror at the idea of hallucinogens being an important subject in the Sumerian texts and that he would bring up the sad fate of John Allegro’s book, The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross, back in 1970. Nothing has changed since then. It is still the only reference. No-one could seriously expect him to be open-minded on this. It’s done and dusted.

Graham recently posted a facebook link to Dr. Finkel’s latest offering concerning apparently weak-minded Babylonians staring at distant pointy mountains (in the 8th century BC), thus providing the address of Noah’s mountain landing. I’m an unknown quantity and don’t fit into either circle, orthodox or alternative. The fact that I’m not someone who enjoys public speaking and would certainly be no match for a natural entertainer like Irving Finkel doesn’t help. It would take quite a few puffs of something sweet – or a bowl or two of something bitter – to get me (knowing what I now know) to fully appreciate the wisdom and friendly humour of the good doctor’s words, those that quite understandably make him such a hit with everyone else.

That said, I enjoyed reading The Ark Before Noah and I did send him a copy of The Story of Sukurru (aka The Instructions of Shuruppak) via the British Museum back in 2017. I got no feedback but didn’t expect any. The Sumerians are not supposed to have written about Noah’s flood as early as 2600 BC. It doesn’t fit the current accepted narrative as discussed in his book, so I certainly wouldn’t expect him to be open-minded on that one either. We are worlds apart in every way. But you made me smile so there’s always that!

Thank you for your kind words.

Thanks for explaining, Madeleine. I am sure your audience would still love it, whatever your reservations. That argument (he says the date is X, I say it is Y) would be worth it alone.

I also meant actually getting Dr Finkel high on psychadelic mushrooms, directly, to help with the opening process. Book learning is one thing…but when the books are wrong?

I wonder if this may be relevant:

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2024/11/12/evidence-human-writing-1000-years-earlier-summeria/

In the Telegraph article:

“Did seal imagery contribute significantly to the invention of signs in the first writing in the region?”.

Yes, indeed. It’s the same subject and why they appear to find the link between cylinder seal images and the early script so surprizing is beyond me. It’s difficult to believe that no-one noticed this many moons ago in the backroom of a museum somewhere. I’m truly gobsmacked that this is being presented as a new finding.

Also the earliest known writing system is not ‘thought to be Sumerian’ as she writes – it IS Sumerian (emphasis on ‘known’).

Thank you for pointing this out, Philip.