- Land of Milk and Psychedelic Honey: Part 3 of Images from Göbekli Tepe and Other Neolithic sites reflected in Sumerian pictograms and texts

- Images from Göbekli Tepe and Other Neolithic sites reflected in Sumerian pictograms and texts – Part 2. Pagan Wings and Sailors’ Feet

- Images from Göbekli Tepe and other Neolithic sites reflected in Sumerian pictograms and texts – Part 1. The Pillar and the Snake

It was a border guard who stopped Lao Tzu as he was riding off on his water buffalo never to return and requested that he write down his words of wisdom before leaving China. (Lost Stones of the Anunnaki, p.218-219)

But first….

It should go without saying that anyone attempting to translate a dead language while remaining oblivious to its subject matter will have strictly no chance of succeeding. At best, the truth will be only partially revealed. At worst, it will be covered over with vague and unverifiable nonsense.

In the course of studying the Sumerian script and texts, it has become evident that the interests of the scribes included several themes of which I had very little or no previous knowledge—and that they were invariably absent from the academic translations. I have spent a fair amount of time wondering if the lacunas were honest mistakes or deliberate omissions by past philologists and have come to the conclusion that it was a bit of both. On one hand, the people who first took on the task of translating this unknown language in the mid-19th century were probably quite as ignorant as I was on subjects such as astronomy or mind-altering substances. On the other hand, perceiving certain potentially contentious themes better known to all, subjects that would automatically lead to awkward questioning of received wisdom in matters of religious beliefs and world history, those new-born ‘Sumerologists’ might well have chosen to strategically place a large obstruction to prevent further delving down such rabbit holes.¹ That is just a theory, but reasonable nevertheless.

Over a hundred years have passed since Joseph Halévy, a French orientalist, first disputed the existence of Sumer and fifty years since John Marco Allegro’s similar claims that this was not an isolated language. Equipped with an enquiring mind and internet at my fingertips, some basic academic training in linguistics and art history, along with prior translating experience in the relatively complex domain of economics, I am not cowed by opaque prescriptive grammar rules conjured out of very thin air a century or two ago by a small bunch of 19th century amateur philologists, still today presented by their peers as uniquely trustworthy. My counter-arguments are plain and substantiated; the early language was monosyllabic, the clever positioning of its words is the key to understanding how it should be interpreted, and so-called Sumerian is the opposite of isolated. It is the mother of them all. As mentioned in part 2 of this series, John Marco Allegro most certainly got some things right.

I am reminded of Lenie Reedijk’s comments on the unwelcome truth of Malta’s history:

These new dates made the temples older than Crete, but this inconvenience was got around by declaring that Malta was an isolated phenomenon. The word ‘insularity’ in relation to Malta’s early prehistory, with all its desired connotations, became very popular all of a sudden. 2

Moving on…

There are several forgotten or underdeveloped themes that must be re-integrated into future retranslations of the early Sumerian/Mesopotamian literature if we are to move forward in our understanding of their world view—not to mention get a decent and respectful grasp on their degree of sophistication, far beyond anything that has so far been suggested. Given here in no special order, some of the missing puzzle pieces:

– early knowledge of the precession of the equinoxes,

– celebration of the death and rebirth of the sun at the winter solstice,

– baptism, the birth and role of Sirius, irrigation and fertility,

– the importance given to cattle, bull-leaping, the brazen bull, the milk of life and death,

– bees, their essential regeneration after extinction events, the honey of life and death,

– celestial ships, the founding story of Egyptian-born Danaus, journey of the Argonauts,

– shamanic initiation rituals involving the use of psychedelics,

– philosophical teachings, the importance of truthful recording of events above and below.

Some elements of these themes can also be quite neatly matched to the preoccupations of the pre-Harranian culture ca.9600 BC as perceived through the newly unearthed images in that region of the world. Paganism did not come into being with the Roman Empire. Did it have its roots in the region of Harran? Was it reborn there after some earth-shattering event?

At the time of translating The Story of Sukurru (2014-2017), the astronomical aspect was absent from my version of the multi-layered text. Like others before me, I was blissfully unaware of the phenomenon of precession and frankly, without the information gleaned from the writings of Graham Hancock and particularly Magicians of the Gods published in 2016, I would not have been able to reintegrate it into Maestro of a Lost World, my second translation published in 2024. The degree to which astronomy is still largely absent from debates about our most ancient texts is unfortunate. Has no one else noticed that the positioning of the lines and other numbers in the Sumerian King List, inscribed ca.1600 BC, form an integral part of the numerous encoded references to the 25,920-year cycle of the sun? Are we really still all wondering what vitamins those kings were swallowing in order to live so long?

This is the Way

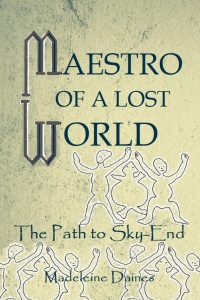

This exquisite profile above a woven basket (fig.1) inscribed in clay over five thousand years ago was used to illustrate the chapter of Lost Stones of the Anunnaki (2021) in which Lao Tzu, supposed author of the Taoist texts, was mentioned along with Saint Anthony of Egypt and other similarly mythical or existing monk-like figures from various places.3 Only the outward gaze was added for effect:

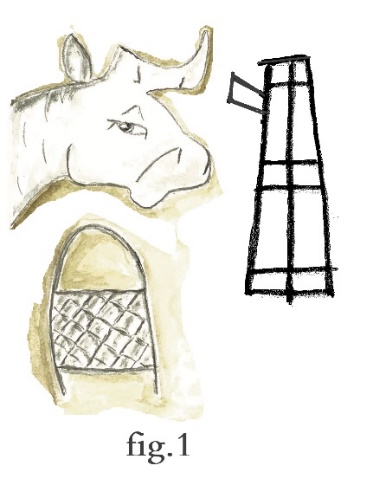

The tablet comprises just three words. The head with the single visible horn resembles that of the animal on Indus Valley seals, usually described as a unicorn. Transliterated here as JIR₃/GIR3, it has the meaning ‘path’ and ‘way’ (among others). I take it to be either a bull or cow.

There are other words directly relating to cattle in the Sumerian lexicons, demonstrating the importance given to the species. As shown in the discoveries at Catal Höyuk, Göbekli Tepe and elsewhere, the Mesopotamians had that in common with the earlier inhabitants of the region.

GUD (fig.2) has the dictionary-given meanings ‘bull’ and ‘cattle’. With the word KUR, pictogram of three mounds or ‘hills’ at its heart, it’s read as AM (fig.3) and becomes a ‘wild bull’. The Taurus Mountain range, source of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers to the north of Harran and Göbekli Tepe, is a fit along with the untamed constellation of the same name. Taurus appears in the sky with its horns tilted in the direction of the belted human figure of Orion.

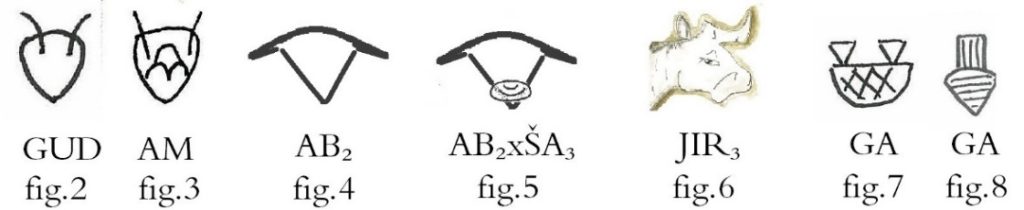

Then again, when found with TA, the sign of questioning and death, AM lies opposite the word given as phonetic TAM (substantiated by the lexical tablets). TAM is another of the numerous phonetic values attributed to the pictogram that I invariably name as UD (see the brazen bull here below) and translate to ‘sun’.

Thus, TAM/UD, when understood with the underlying meanings of TA-AM, can translate according to context to:

– questioning of the (prophetic) bull,

– death of the wild bull,

– death of the sun.

Then he brought me to the door of the gate of the Lord’s house which was toward the north; and, behold, there sat women weeping for Tammuz. (Ezekiel 8:14)

Sumerian MUŠ has the given meaning ‘snake’. Is this the true origin of the biblical name Tammuz rather than the suggested Akkadian Dumuzi, composed of two words that translate to the ‘risen or rising son’? Did the women of Göbekli Tepe weep for a great red bull as it died and disappeared back into the womb some eleven thousand years ago? Did they beg for the fertility that would result from its rebirth after the third night of mid-winter? Was it the sun?

AB2 (fig.4) translates to ‘cow’, but it strikes me that all these words should naturally extend to all members of the species at whatever period, to aurochs and hump-backed zebus and, according to context, to either sex. Exceptionally, to accommodate the mysterious Chinese philosopher, Lao Tzu, I would add in the water buffalo. This abstract frontal view of the head with lowered horns can be usefully matched to the contorted perspective of the heads carved in the various archaeological sites of southeastern Turkey. No leader worth his salt leaves for another land with his people but without their precious herd of cattle.

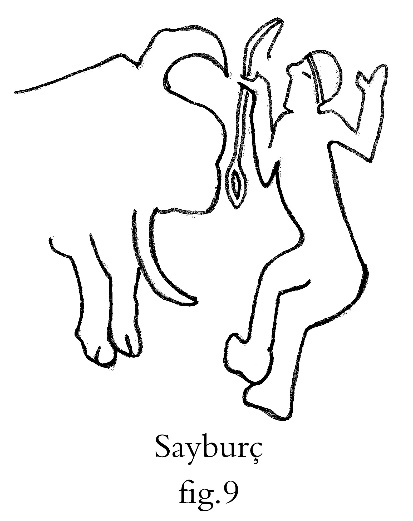

Additional information can be gleaned from the wall carvings discovered at Sayburç, where part of a bas-relief carving has a bull facing a leaping figure holding what appears to be either a snake or a looped rope. That section of the wall is strongly reminiscent of the Orion and Taurus constellations and, given the estimated age of Sayburç at around 9000 BC, might even have been the original inspiration for that choice of celestial metaphor employed over thousands of years:

Bull-leaping was mentioned in The Story of Sukurru in the context of a pagan ritual of passage to adulthood. That section of text refers to the milk from which the youth has recently been weaned. The Sumerian word for ‘milk’ is GA (fig.7 and 8). In this case, it’s taken to be the milk of a celestial cow, a psychedelic brew served by a shaman. Did the shamans sit on elevated stone slabs and preside over competitions involving the possibility of death from the horns of a bull? Did they begin some type of solemn ritual by offering a very special brew to the young adults to give them courage? Did initiates into a pre-Eleusinian mystery school drink the milk of life and death in the land between two rivers?

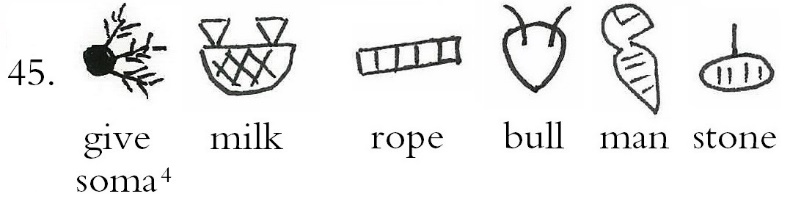

In the context of a ceremony where the beer cask is carried along by a band of merry pagans (both beer and bull were transported at the heart of the river and sea-faring vessels), here below a section of line 45 of The Story of Sukurru from ca.2600 BC. (The only version still in existence today was written in the more abstract cuneiform of that time.) It includes the words GA (fig.7) and GUD (fig.2):

(The male who is) weaned a rope around the (heavy or) stone bull man (raise).

This was primarily understood as a reference to youngsters testing their courage against bulls that somehow took the form of the original and hard-working Mesopotamian lamassu, the slightly comedic ancestors of the great winged statues guarding the entrances to temples and now largely unemployed in our museums. They were always on call (to call out the phases of the moon) and mentioned several times in that tale.

Churning the Milk Ocean

Here below, using a different version of GA (fig.8) also found on 4th millennium tablets, is a reference to the Milk Ocean that dedicated workers must churn. Line 97 of The Story of Sukurru includes the three-word phrase GA-RA-AB:

This age-old and predominantly Indian theme is linked to the phenomenon known as the precession of the equinoxes. In summary, the phrase GA-RA-AB refers to:

– the churning of the Milk Ocean (Milky Way) by means of a rope or gigantic snake, symbolic of the passage of time, noted at regular intervals (precession of the equinoxes),

– the push and pull of frothing tidal or storm waves against which sailors fight by means of the ship’s ropes,

– fertility of the adult male, AB as both ‘sea’ and ‘Father’, the phrase reading ‘milk of the father’, potentially leading to Priapus in his earliest phallic depictions and role as guardian of sailors (see part 2). AB can also be understood in this context as the ancestor of Greek Poseidon. Its hourglass pictographic form resembles the lower body and belt of Orion.

There are many layers to the overall story. It involves:

– the first step on the path of the mythical journeying hero,

– the first lesson of the initiate swallowing the psychedelic brew,

– the flight of the birdman in tandem with the sun,

– the groom with his dowry preparing to join his bride,

– the ship setting sail for the unknown,

– the giant figure of Orion preparing to bring down the constellation of Taurus.

The opening lines 11 and 12 of Maestro of a Lost World (Enki’s Journey to Nibru) confirm that the path from earth to sky – and return to the ultimate womb at the southern end of the Milky Way – begins with the three prominent stars of Orion’s Belt as worn by the proud man himself. Orion has been described as a rooster. The first challenge is to reach the cluster of the Pleiades on the shoulder of the bull, also to be understood as the starting point for calculations of the 25,920 years of the sun’s backward flow through the twelve constellations in its path. The push and pull of a celestial rope move everything along over time.

The Final Challenge

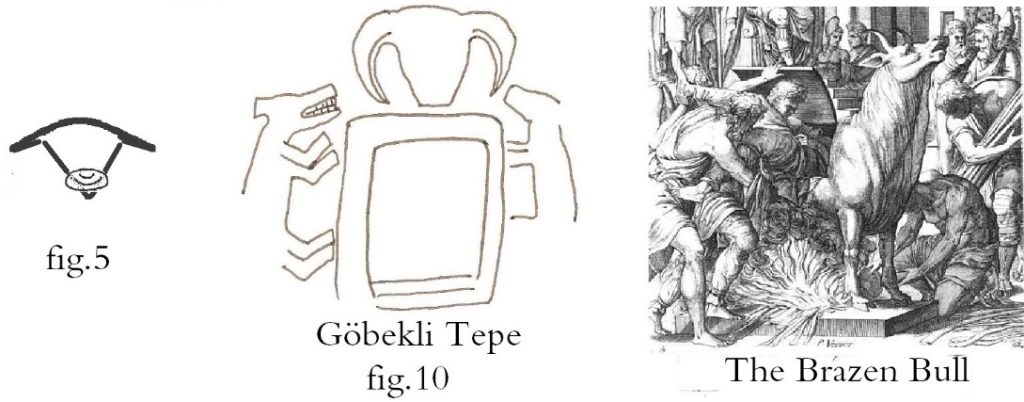

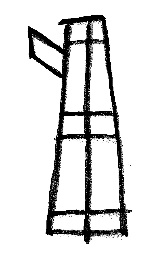

Another bull’s head (fig.10), this one at Göbekli Tepe, sits above a rectangular hole reminiscent of a shrine or an oven door. Two barking canines, dogs or foxes, surround the box:

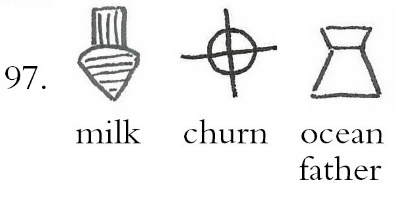

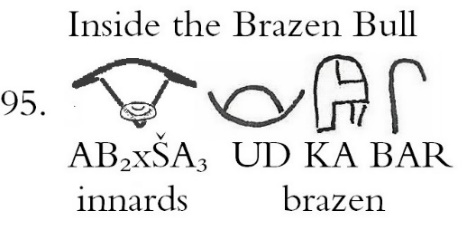

AB2 with ŠA₃, ‘inner’, at its centre (fig.5), translating to the ‘innards of the cow or bull’, is the first composite word of line 95 of Maestro of a Lost World (Enki’s Journey to Nibru). There, it’s immediately followed by a qualifier, a three-word phrase transliterated together as ZABAR. ZABAR has the dictionary-given meaning ‘bronze’, resulting in the easily verifiable adjective ‘brazen’. At the same time, and if a specific context were to allow for it, the words UD-KA-BAR might be taken individually to mean: the ‘distant speaking sun’ or the ‘distant heated word’.

Appearing in the immediate aftermath of a comet strike on line 93 and neatly fitting into the catastrophic context of that rediscovered story, they become:

The concept of torture in the brazen bull, thought to have existed in Ancient Greece, involved locking the victim inside a hollow bull made of metal and lighting a fire underneath (here above on the right an engraving by Pierre Woeiriot, 16th century). The shrieks of pain were filtered to sound like the bellowing of the animal. Among several saintly names and strange stories of forced journeying attached to this unholy instrument known as the Bull of Phalaris, that of Saint Antipas of Pergamum, a city near the Mediterranean coast in modern-day Turkey, is perhaps the most famous (see the cover image of a fresco in the Monastery of Rousanu, Greece). His fate is also mentioned in a passage from Revelation:

I know thy works, and where thou dwellest, even where Satan’s seat is: and thou holdest fast my name, and hast not denied my faith, even in those days wherein Antipas was my faithful martyr, who was slain among you, where Satan dwelleth. (Revelation 2:13)

In astronomical terms, the constellation of Taurus and the sun are brought together – possibly at the height of summer or more generally at a time when the sun appears in the company of the bull, either solstice or equinox. Either that was the inspiration for the Göbekli Tepe scene, or the story behind the brazen bull was already a distant and unique memory in 9600 BC; that of the devastation of the earth through the impact of one or more comets from the Taurid stream.

Maestro of a Lost World integrates astronomical knowledge along with the underlying shamanic theme of the initiate’s dangerous journey to experience death before rebirth, also reflected in Ancient Egyptian mythology. For the disciple, this is the final and the most harrowing ordeal of them all and, under the circumstances, UD the sun–the pictogram of which is close to an upturned version of the bull symbol—might also reasonably translate to ‘unbearable heat’.

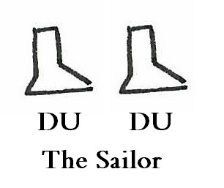

The sailor, whether in human form as the initiate or as a dematerialized soul at death, eventually passes through the second birth canal. This time, his ship will face the clashing rocks strewn along the Dark Rift at the heart of the Milky Way, defeating low-vibrational enemies along the way and the false relief that they offer. Inevitably, he will pass through a black swarming cloud and the angry buzzing sound of newly released bees before sighting the coast of his homeland beyond. Unless of course, blinded and weakened, he has long since lost sight of his goal and is stuck on an unforgiving ocean with only fear for company. But in true Homeric style, triumphant and fearless, the hero prevails. And yet strangely, spurning a trumpeted welcome, Odysseus chooses to return home as silently as a mouse.

Sweet Death

So I took the small scroll from the angel’s hand and ate it; and it was as sweet as honey in my mouth, but when I had eaten it, my stomach turned bitter.

(Revelation 10:10)

Milk and weaning are mentioned in The Story of Sukurru in the context of bull-leaping ceremonies. From an earthly viewpoint, the mother, whether cow or human, nourishes the newborn with sweet milk from her breast. But in that multi-layered story, the young man has already moved on from childhood and has now drunk a more potent and bitter brew, thanks to which he will muster his courage and take a leap forward to the next stage. He must master the experience of death in order to defeat the fear that haunts us all in life.

Pictographic HI/HE takes the form of a mandorla (an almond shape that is well attested in later religious imagery) on 4th millennium tablets and has the dictionary-given meaning ‘mix’ (among others) to which I have added an all-encompassing ‘veil’ for several reasons, of which the source image along with its positions and collocations in the texts. Here is found the first syllable of the name of far later Greek Hebe, goddess of eternal youth who mixes the drinks for the inhabitants of Mount Olympus. Sumerian HI also resulted in the first syllable of our words ‘hymen’, ‘heaven’ and the ‘hive’ where the original queen’s descendants still reign supreme, safe behind their thick veils of wax.

BI has the dictionary-given meaning ‘beer’ to which I add a less connoted and infinitely more intriguing ‘brew’, always useful for lifting a veil… and ‘bee’. And yes, the two words are found together in the Sumerian texts (lines 17 and 61 of Enki’s Journey to Nibru). Hebe’s main feature – forgotten or supressed – is that she is, in fact, a great queen bee and her much appreciated speciality is the sweet and bitter, life and death giving honey cocktail.

I wonder when the Harranians first thought of building their homes in the form of beehives. Perhaps it came to them long after their ancestral neighbours further north first climbed the Pontic Mountains, not far from the Black Sea, to steal that rare commodity now known to us as ‘mad honey’. Harvesting honey from wild bees that feast on the nectar of a specific species of rhododendron flowers is a tradition that has long existed in just two regions of the world: Turkey and Nepal.5 At least, those are the only places where it still exists today. Perhaps in a far-distant past, there were many more. I wouldn’t be at all surprized.

With a very slight stretch of the imagination, the home of the mad-honey bees just north of the Taurus mountains might even be said to mirror on earth the clusters of the Pleiades and Hyades buzzing around their hives above the constellation of Taurus in the sky. From there, we might wander further still and imagine that the ithyphallic bird-headed figure on the cave wall at Lascaux in France was preparing to climb a mountain – a metaphorical bull – in order to harvest the honey of the Pleiades and Hyades beyond.

Whether the ancient rock-climbers along the southern coast of the Black Sea made that association with the night sky or not, they were necessarily aware of the psychedelic, deathlike effects of their harvested honey and, more generally, grateful for the recurring gift of life that the loud springtime buzz of the wild honeybee has always represented.

Bees cling to life as best they can despite the constant threat of annihilation, whether through the stupidity of humankind or some other natural disaster. Sometimes the situation seems particularly perilous. Perhaps this time will see the end of them forever… In ancient tales such as Virgil’s Georgics it was said to be possible to bring the colony back to life through a strange process involving the innards of a rotting bull’s carcass, strikingly reminiscent of the story of the brazen bull found in Maestro of a Lost World, associated there and elsewhere with an apocalypse. Coincidence?

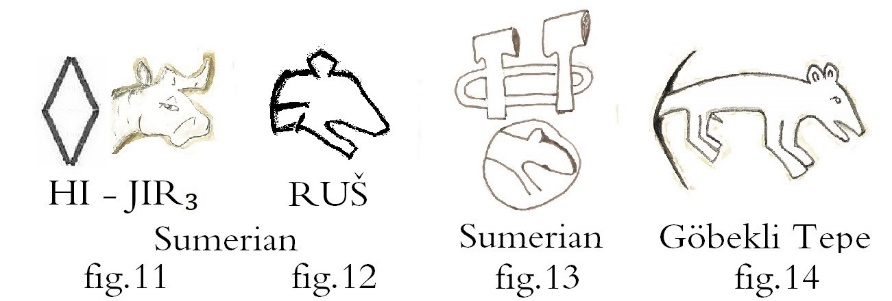

Exodus

JIR₃, the ‘path’, combined with HI, the ‘veil’ and ‘to mix’ (fig.11), transliterated together as HUŠ or RUŠ (fig.12), have the dictionary-given meaning ‘reddish’. The combination leads to a few possible translations – always according to Sumerian lexicons and the context in which they are found – of which the ‘veiled path of the bull’ or potentially the ‘journey beyond the west’ if we consider the ‘reddish path’ to be that of the setting sun. But which bull is this?

Again, the phrase is evocative of the giant human-headed bulls planted on either side of the gates giving access to ancient Assyrian monuments. They have wings and horned helmets and watchful eyes. Hold your hat in your hand while you state your name and purpose. If they don’t like the look of you, prepare to be booted into the night skies. Or better still, trick them by passing through rapidly, in silence and by night – like a fox or a mouse.

The word ‘hijira’ in the ancient Arabian lunar calendar has the meaning ‘departure’ or ‘exodus’. Translated with a capital H, Hijira is the name given to the year 622 CE, marking the start of a new calendar to coincide with the beginning of Muhammad’s journey to Medina. The overall sense of the word is a ‘flight to a better place’. I suggest that its origin—as with a good number of other Arabic words also in logical contexts—is found in the composite Sumerian word HI.JIR3 (fig.11), the passage through and beyond the veil. However, there appears to be some confusion over whether these two words together are the same words that gave transliterated HUŠ/RUŠ (fig.12).

Unfortunately, fig.12 is the only version I was able to copy from the pictographic period of the Sumero-Akkadian script. Neither have I succeeded in locating the tablet from which this 4th millennium version (sourced from L’Ecriture Cunéiforme 6) was borrowed. And despite proof of the connection to the words HI with JIR3 (according to modern lexicons), the emerging animal does not appear to be a bull. It looks considerably more like a rodent. Nevertheless, whether mouse or bull, fig.12 goes a long way to demonstrating that the word did exist in pictographic form. A further connection to both the pre-writing Sumerian era and Göbekli Tepe can be made thanks to fig.13, which appears immediately below the enigmatic rendering of two encircled pillars on a seal from the 4th millennium or potentially earlier (already mentioned in part 1). That image, also having the appearance of a rodent emerging from a hole, makes an excellent candidate for the source of the word RUŠ as found in L’Ecriture Cunéiforme.

Fig.14 is a carving on one of the twin central Göbekli Tepe pillars in enclosure D. That animal, usually thought to be a fox and thus another attested trickster, is sneaking out from under the crook of the right arm of the belted figure. But can we be sure that it’s a fox and not a mouse or, better still, a snow-white ermine wearing its magical mid-winter coat?

Keeper of Time

There are just three words inscribed on the tablet shown here as fig.1. The bull in profile is the ‘path’ and the ‘way’, while the woven basket below is transliterated as DUB, a word that translates to ‘tablet’. That image would have been better transliterated to MAL/GA₂, the ‘basket’. Nevertheless, the confusion is interesting in that it highlights the visual similarities between the earliest words for both the clay tablet and the woven basket (as already mentioned in Part 1). Tablet and basket as vessels were closely linked, if not interchangeable, at some point and for some reason.

The third word to the right of the bull’s horn is ŠID or SANGA, an intriguing pictogram with a broad range of transliterations and meanings. I take it to be primarily the verb ‘to count’ or its noun, the ‘accountant’; an administrator of some sort, the manager in a warehouse, for example. It’s found at the end of line 103 of The Story of Sukurru and in the context of enunciating a list of instructions to pre-biblical Noah. In that version of the text, ŠID was named the ‘lofty administrator’.

Another transliteration for this word, SANGA, breaks down into two further monosyllabic words: SAN, the ‘head’, and GA2, ‘basket’. Taking the basket to be a sailing vessel and the head to be both that of the bull and a leader, then the scene of Lao Tzu on his water buffalo preparing to write his instructions at the beginning of a journey has obvious similarities.7

The correct and truthful recounting of events above and below is not up for discussion. It was written in stone a long time ago. The annihilation of bees—along with every other creature still stuck here on earth—was foretold, and an exodus prepared, entailing the construction of a massive boat. This is a prominent theme of the Sumerian literary texts and not confined to just a few fragmentary clay tablets rediscovered by chance here or there over the past centuries. That small, neat lump of exquisitely inscribed clay (fig.1) demonstrates the intimate connection between a figure of authority, the path of a bull and a vessel containing something or other.

A journey of a thousand miles begins from under the feet. (Lao Tzu)

Notes and References

¹ In the last quarter of the 19th century, under the control of a small group of people, all discussion of the newly discovered cuneiform writing system was smoothly shaped to fit a narrative. The ultimate root of Akkadian, found in a less abstract form of the script and dating to the 4th millennium BC, was side-lined, renamed ‘Sumerian’ and treated as a ‘language isolate’. The authors of that error or deception ensured that no outsider would have the means to look more closely. A glimpse of a passage here or there bearing similarities to far later biblical themes, such as the flood story, would not arouse unwanted curiosity.

But one person did take a stand and refuted the ‘Sumerian’ label. Joseph Halévy, a French orientalist, claimed loudly and for some forty years until his death in 1907 that this was the earliest expression of one evolving language and that Sumer had never existed. There was no proof of it. Halévy was accused of being primarily racially motivated in making such a preposterous claim. His refusal to recognize that the invention of writing belonged to an otherwise unattested people from the 4th millennium BC was fuelled by his desire to attribute that great exploit to so-called Semites. To put it another way and to return the compliment to his accusers, the argument over the authorship and family ties of a writing system from 3500 BC stemmed less from a close study of the language itself and more from a 19th century struggle involving the racial tensions of that epoch.

If he (Halévy) could not escape what was certainly a correct presumption that his anti-Sumerist thesis was motivated by his origins, he had every right to expect that he would be refuted on a scholarly basis, and that his views would not be twisted to make him out to be not only wrong, but a racist.

(Jerrold S. Cooper, Sumerian and Aryan: Racial Theory, Academic Politics and Parisian Assyriology, 1991)

The 19th century claims concerning the existence or non-existence of Sumer went so far astray from analyses of the language that they included the physical aspects of the figures on Sumerian and Akkadian artefacts. But even if the argument had been confined to a study of the rediscovered language, the result would have been the same. They all had personal, cultural and religious motives, including Edward Hincks, the Irish clergyman, one of the so-called ‘holy trinity of cuneiform’. Joseph Halévy was ridiculed and, after his death, his theory forgotten. As was that of John Marco Allegro, a reputed philologist at the University of Manchester, some seventy years later.

Allegro’s infamous book, The Sacred Mushroom and The Cross, in which he suggests that the Sumerian writings had Jesus down as a magic mushroom, was a mere blip in a well-constructed and entrenched narrative by the time his work was published in 1970. Add the fact that, despite his specialization in ancient languages, Allegro’s grasp on Sumerian was tenuous at best. The highly debatable examples given in his book bring proof of that. In my opinion, he perceived more than once that something important was missing during his studies of the various religious texts recovered from Qumran, but was unable to follow through with unassailable proof that it all derived from the Mesopotamian writings. Unfortunately, he was also convinced of the overriding importance of the phallic fertility deity and had not discovered the presence of other equally central subjects. Ridicule came easy.

2 https://grahamhancock.com/reedijkl1/

3CDLI (Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative) ref. P002207, Uruk IV ca.3350-3200 BC.

4 The correct etymology of the fabled soma, drink of the gods, is provided by the Sumerians from SUM (pictographic form on the left) which has the dictionary-given meaning ‘give’ and ‘to be drunk’ (among others). SUM is more generally associated with MA, the ‘land, a pictogram that takes the form of a hanging fruit, most likely a fig.

5 https://edition.cnn.com/travel/turkey-mad-honey-deli-bal/index.html

6 Lucien-Jean Bord & Remo Mugnaioni, L’Ecriture Cunéiforme, Syllabaire Sumérien, Babylonien, Assyrien (Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner S.A., 2002.)

7 That image is also closely similar to the numerous Indus Valley seals showing the profile of a ‘unicorn’ above a sailing boat.

- Land of Milk and Psychedelic Honey: Part 3 of Images from Göbekli Tepe and Other Neolithic sites reflected in Sumerian pictograms and texts

- Images from Göbekli Tepe and Other Neolithic sites reflected in Sumerian pictograms and texts – Part 2. Pagan Wings and Sailors’ Feet

- Images from Göbekli Tepe and other Neolithic sites reflected in Sumerian pictograms and texts – Part 1. The Pillar and the Snake

your book looks amazing. i will be ordering soon

Thank you, Michael. And thanks again for posting the photo of the ‘bag’ on the Mysteries Board as requested – very interesting. Part 4 of this series will explain the three bags on pillar 43 according to the Sumerian account in The Story of Sukurru.