My first re-translation of a Sumerian literary text, titled The Story of Sukurru (aka The Instructions of Shuruppak) and self-published in 2017, has been safely dated to ca.2600-2500 BC thanks to the discovery of fragments written in the style of that period. Thus, it is also proven to be the most ancient literary text in the world, as well as the earliest record of a reference to Noah’s ark. Despite a number of claims for other far later languages and other stories from different regions, there is no contest. Nothing comes anywhere near the age of the written language of the Mesopotamians. And whether qualified as ‘Sumerian’ or ‘Akkadian’ (both meaningless names generated in modern times https://grahamhancock.com/dainesm11/), it must not be forgotten that the same script was uniquely employed throughout both southern and northern Mesopotamia from the middle of the 4th millennium BC right up to around the middle of the 1st millennium BC. The style of the writing evolved, progressing from relatively complex pictographic forms to the tiny straight strokes known as cuneiform, but the founding stones, along with their encoded messages, are still in place. Despite the major archaeological discoveries of the 19th century and the many thousands of those tablets now in hand, at its heart, the language holds a mountain-full of treasure that has still not been fully exposed.

In his book, The Ark Before Noah (p.33), Dr Irving Finkel, a well-known British Sumerologist, mentions the ‘persistent confusion’ that once prevailed over the differences (or lack thereof) between Sumerian and the later Akkadian, and – most interestingly – whether or not Sumerian was more of a code than a language. Apparently, that small matter was settled to everyone’s satisfaction by the appearance of ‘sign lists’, ‘advanced grammars’, and ‘weighty dictionaries’. To my mind, those terms signify only that the plain and infinitely more simple truth was buried under the overwhelming weight of scholarly obfuscation. But who am I to make such claims? One formerly well-respected philologist, John M. Allegro, also went rogue in 1970, making a direct connection between Sumerian and ‘subsequent Middle Eastern languages’. His infamous book, The Sacred Mushroom and The Cross, claiming a link between pre-Christian pagan fertility rites and later religions, with its references to the consumption of hallucinogenic mushrooms, was loudly and angrily dismissed by other academics. Then the noise died down, Allegro’s promising career within academia was over, and life returned to ‘normal’. (https://grahamhancock.com/dainesm5/)

In the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, England, there exists a four-sided tablet covered in tiny cuneiform writing. Recognized as one of several versions of Enki’s Journey to Nibru, it provides irrefutable proof that the Mesopotamian scribe who so carefully transcribed its 129 lines was fully aware of the astronomical phenomenon known to us as the precession of the equinoxes – knowledge commonly attributed to Hipparchus in the 2nd century BC. And that is just a part of the information about the ancient astronomer-scribes provided by that artefact.

What follows is an extract from the introduction to my second re-translation of a Sumerian literary text, this one renamed The Path to Sky-End (aka Enki’s Journey to Nibru). It is thought to be some 1,000 years younger than The Story of Sukurru, the earliest version appearing only in the Old Babylonian period, ca.1800-1600 BC. However, the two texts carry the same incipit and have a number of phrases in common, leading me to firmly believe that they stem from the same original source story, probably from the same time period, i.e. they are both at least as old as the earliest date given to the construction of the Great Pyramid of Egypt, a fact that is relevant to their contents. The author(s) was very much aware of the existence of the Giza plateau, and references to it were encoded in these texts.

The Path to Sky-End has one immense advantage over others from the same time period. It has survived the intervening millennia virtually intact, missing only two words from its 129 lines. In a short chapter of the long introductory section to the translation in my latest book, Maestro of a Lost World, I wrote:

Mention of a comet strike here is entirely the result of having come across one by chance during the translating process. It is not in any way an endorsement of Zechariah Sitchin’s theory about a twelfth planet. Does this account have any bearing on the cataclysmic events of around 12,000 years ago? I will leave readers to make up their own minds as to that possibility. The translation in its context is accurate. That’s all I can and do claim.

Hiding in plain sight on line 93 of The Path to Sky-End (aka Enki’s Journey to Nibru/Nippur) under the guise of a great lump of mortar is an account of something extremely destructive hitting our planet. The defining word in that account is transliterated KUM which I posit is one source of Greek kometes meaning ‘comet’.

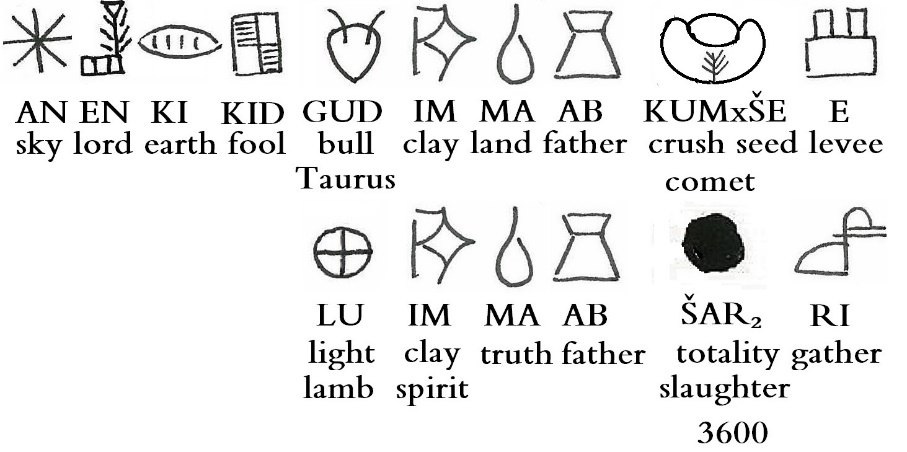

KUM has dictionary-given meanings of ‘mortar’, ‘crush’ and ‘kill’. With ŠE (meaning ‘seed’) added inside it, transliterated KUM was given the name GAZ, the seed-crusher. Its pictogram (here above) looks for all the world like a grinding bowl containing a heavy stone ball. No doubt that’s what it was, a kind of mill, a stone crusher. In context, the word is found with mention of a bull and, in my opinion, also served as a description of castration. But behind all such meanings lies the original account of a life-altering strike of either a single comet or a series of huge meteors.

Adding in a fair dose of healthy scepticism, given the importance of the subject, there can be only one follow-up question. If this claim is true, why would we find mention of such a vital piece of astronomical information on only one of the hundreds of thousands of tablets in our possession today? That was the question I asked myself immediately after discovering it and seconds before feverishly combing through the corpus of Sumerian texts. It didn’t take long to find three other comets firmly embedded in three other texts, all incorporated into lines which are absolutely identical to line 93 here.

So, four texts in all…and that’s just the number of versions that have survived through thick and thin for around four thousand years. Impressive. Having four separate examples of that line still available to us today and taken from four different texts is adequate proof of its importance.

Only the first four words, title of the lord between sky and earth (AN-EN-KI-KID) in this version are exchanged for the ‘lofty king’ or the ‘king at the levee’ (LUGAL-E) in the three other texts, a useful variation confirming that the two epithets applied to the same figure; the lord and the king are one and the same.

Here below the slightly varying and thoroughly underwhelming academic translations, with KUM/GAZ given as the verb, ‘to sacrifice’ and ‘to slaughter’; the fatal comet totally invisible in those localised and relatively contextless scenes:

– The Flood Story, line 11 (ETCSL ref. 1.7.4, Seg.D):

The king sacrificed oxen and offered innumerable sheep.

– The death of Ur-Namma, line 81 (ETCSL ref. 2.4.1.1):

The king slaughtered numerous bulls and sheep,

– The debate between Hoe and Plough, line 25 (ETCSL ref. 5.3.1):

The king slaughters cattle and sacrifices sheep

– Enki’s Journey to Nibru, line 93 (ETCSL ref. 1.1.4):

Enki had oxen slaughtered, and had sheep offered there lavishly.

My monosyllabic version of Enki’s Journey incorporates all relevant meanings of those twelve words (i.e. excluding the king and lord), and makes use of each of them more than once – taking them to their absolute limits to ensure that not one ounce of the original meaning is lost. In that, it is diametrically opposed to the academic conventions where many of the original, meaningful words are taken to be meaningless phonemes, nothing but sounds. Those translations (including king and lord) amount to fewer words than the original – between seven and ten – a difference resulting only from the use of the causative verb form in Enki’s Journey.

This translation has the immense advantage of appearing in its true original context of astronomical observations. The king or lord is given in the passive tense, berated and threatened by a far greater and extremely annoyed entity. For those reasons, the result is considerably longer (forty words!) and infinitely more impactful than the officialised versions:

93. “The foolish lord between sky and earth, for mortar to make clay of the land of both Mother and Father, his seed with the seeds of the bull (Taurus, Taurids) will be crushed in the levee, and the lambs in clay of land and sea all gathered and slaughtered!”

The mortar for reconstruction work after the announced cataclysm will be made from the clay, diverse bones of the victims, etc., all mixed with the raging flood waters. A reminder that the Mesopotamians were not only astronomers. They were experts in irrigation techniques and they built their pyramids with fired bricks joined with mortar. Despite appearing just once, the original word KUM/GAZ was used four times here for ‘mortar’, ‘seed’, ‘seeds’ and ‘crushed’, all firmly linked to one another and all dictionary-given meanings.

Never forgetting – on a lighter note – the other underlying and age-old theme identified in this text: that of the fearless (some would say mad) honey-hunter on his reed-woven ladder clinging precariously to the cliff face while using a fire stick to smoke out the bees and to recuperate their honeycomb – an activity provably harking back to ever more ancient times, certainly pre-Ice Age. The protesting swarm was driven out, and the precious comb dislodged with the help of a long prod. If all went well, it fell neatly in one piece into the hunter’s basket. Otherwise, no doubt it fell to the ground far below with a dull thud. Perhaps the hunter too.

Those cliff-hanging honeycombs also look curiously similar to the pictogram of KUM, which is also GUM. This is from Pliny on the subject of beeswax:

The persons who understand this subject, call the substance which forms the first foundation of their combs, commosis, (Pliny, Natural History, Bk XI:6)

The lambs (LU) along with the light (also LU) are exterminated on line 93 thanks to a different but equally dangerous word: ŠAR₂ which also has the dictionary-given meaning ‘to slaughter’, and which appears twice in an equally terrifying context on lines 69 and 70 of The Story of Sukurru:

As with the two phrases of line 93 here, only the names at the beginning of those two lines are different. The rest is identical. Both ‘crushed’ on line 69 and ‘slaughtered’ on line 70 of The Story of Sukurru were translated from ŠAR₂:

69. Dog-Head with a single stone – weight of destiny – with one fell stroke has decided: All of mankind crushed will be.

70. Exalted Sun with one thick stroke on the Stone of Destiny has decided: All of mankind slaughtered must be.

ŠAR₂ is also understood to signify the number 3600 and (just for once) the accepted source of ancient Greek saros, meaning ‘sweep clean’. Apparently, the Greek version of the measurement might not give an accurate reflection of the original numbers:

For 120 saros-cycles make 2222 years according to the Chaldeans’ reckoning, if indeed the saros makes 222 lunar months, which are 18 years and 6 months. (Suda, Trans. C. Roth)

A connotation of chasing out evil and restoring order is present in those biblical verses in which the root of Greek saros appears. In the Parable of the Lost Coin:

Or what woman who has ten silver coins and loses one of them does not light a lamp, sweep (saroi) her house, and search carefully until she finds it? And when she finds it, she calls together her friends and neighbours to say, ‘Rejoice with me, for I have found my lost coin.’… (Luke 15:8-9)

And it’s not impossible that Hebrew zaram meaning ‘to pour forth in floods’, has its origin in ŠAR₂:

The waters saw You, O God; the waters saw You and swirled; even the depths were shaken. The clouds poured down water; the skies resounded with thunder; Your arrows flashed back and forth. Your thunder resounded in the whirlwind; the lightning lit up the world; the earth trembled and quaked.… (Psalm 77:16-18)

There ends the introductory chapter on the subject of the comet strike. And here below is how line 93 is presented for maximum clarity. (The same layout is used for all 129 lines.) It’s comprised of the words as they might have appeared if such a text had been written in the earliest period: the 4th millennium BC. Under the pictograms, the transliterated (from cuneiform to alphabet) versions of those words are added. Then below the transliterations, some (but not all) of the orthodox translations appear. I have added ‘Taurus’ and ‘comet’ for obvious reasons!

Given that the 129 lines of The Path to Sky-End are very clearly laid out to incorporate astronomical themes, of which the precession of the equinoxes and the ‘birth’ of Sirius, it becomes interesting to reflect on the positioning of the reference to this destructive force. The only potential link to the number 93 that I have so far come across is convoluted and perhaps irrelevant. It relates to the Ancient Egyptian calendar, to the heliacal rising of Sirius and to the 1,460 days of that four-year cycle. The calculation is as follows:

365 x 4 = 1,460 or 73 x 20 = 1,460 (73 + 20 = 93)

An indication that the numbers 73 and 20 were indeed used by the Egyptian astronomers is found in the layout of a partially destroyed comb-like structure along the western border of Khafre’s pyramid at Giza. It comprises a series of 73 short parallel walls followed by one separate wall and then, at right angles, another series of 20. The existence of the structure was brought to my attention in a post by Graham Chase on the Mysteries forum of this site:

https://grahamhancock.com/phorum/read.php?1,1331282,1331282#msg-1331282

The original report on the findings by Nicholas Conard and Mark Lehner – The 1988/1989 Excavation of Petrie’s “Workmen’s Barracks” at Giza:

https://www.academia.edu/27674851

The one ‘tooth’ standing alone between 73 and 20 indicates the day that must be added every four years to bring the two independent cycles – of the sun and Sirius – into alignment:

365.25 x 4 = 1,461

Further indication of the reference to the Sothic cycle is found on line 36 of The Path to Sky-End. There the 4th and 5th words, ZA-GUL, taken together (always according to orthodox dictionary-given meanings), translate to ‘tooth’. ZA also has the meaning ‘four’.

The subject of the comet strike is just one of the important themes revealed during the retranslation of this text. There are others. In fact, it’s awash with information, so far only vaguely perceived through the many myths inherited from a lost world. By that I mean only that we have thoroughly misunderstood the circumstances and mindset of the scribe who originally wrote this and no doubt other documents in a far distant past. When? I don’t know. Where? Both Egypt and Mesopotamia. Who? Who knows?

Profound and sublime as usual, Madeleine. Thank you for this fine read. The way language can remain in essence so strong – think of what you say about the syllable KUM, for a start, as in the term, comeuppence, and other uses, including the usual one of approach (especially a memorable one), for example. Yeah, who’s your daddy??

Speaking of twitchy sky-gods, I read a while ago elsewhere (cannot find it now but will update if I do retrieve it) that Thor’s “hammer”, itself an oddity, was most probably originally a memory of some such similar devastating impact object from the skies. As an actual hammer, it makes no sense. As a meteoric catastrophe, though, it does.

Possibly the same one, if we posit the continuance into European tradition of these antique “Sumerian” memories.

Yes indeed. The verb ‘to come’ is traced back through Old Norse koma but comes to a dead end with the ubiquitous and meaningless ‘from PIE’.

No direct link between that Norse word and the Greek comet of course. Too far apart. Two very different channels and a great tribe of knowledgeable linguists and analysts sitting between them, creating catalogues – this one semitic, that one non-semitic, this one proto-Germanic, etc. How could it be imagined that the notion of arriving – or something that comes into being or into sight – in a modern-day language might derive from the same ultimate source as the word for a comet also used in that language?

And yet at the other end of that breath-takingly long knotted cord, the same sounds transliterated to KUM and GUM and a long forgotten pictogram of a mortar and a round stone ball used to crush seed. And the rediscovery of the word in context.

Gilgamesh has a tree or beam along with a double axe hiding in the folds of his name (My article ‘The Trouble with Gilgamesh’). I wonder if that links in with the hammer of Thor. It may well be. If you find other details, I’m always interested.

Thank you for your kind words. Very much appreciated.

KUM might be a rendition of the onomatapaeic sound of the event. K, the abrasive crack as it enters the atmosphere, or impact, OM being sustained resonance of the earth after impact. Those who survived (at a distance) would never forget the sound it made, and would tell the tale with wide eyes and emphasis. An event like that would be visible tangible and audible for many thousands of miles around, even if the common ancestry of Greek and Nordic traditions – all slices of the same PIE, if you can stomach the term – is neglected.

In addition to this, consider the “hammer throw” Olympic sport, in which a round heavy metal comet-like object that resembles no hammer, for hammers are not balls, is cast via centrifugal momentum. This would be more like Thor’s, than that of a smith or knight would be. A hammer that flies, crushes giants and mountains? Easy. Look up!

I am scouring the bookmarks for the Thor article to no avail, but will persist. But along the way I encountered this and find myself marveling at how Sumerian (or whatever) these images look. Not as far apart as synapses in academic skulls might be. https://www.germanicmythology.com/works/EARLYART.html

Found the article: https://www.germanicmythology.com/scholarship/MotzThunderweapon.html

That article is worthy of a long study.

Phonetic KUM derives from the two words found opposite the ‘mortar’ symbol shown here above in the lexical lists: KU with UM, this last given as ‘rope’ or ‘birthmark’ on ePSD (under different phonetic forms but the same underlying pictogram closely similar to the word for ‘tablet’). It’s also the first syllable of ‘umbilical’ as I laid out somewhere (probably in Before Babel).

The word KU is immensely important in both the antediluvian King List riddle (see my OP on the Mysteries forum) and the main riddle of this text culminating on line 108 (indicating a number of importance). Through both the meanings of the lines and the riddle, it takes us across the world to Peru, connecting with South America in 1600 BC.

I feel compelled to add: Does anyone care about the true stories? It seems that most prefer unreferenced fiction and are in raptures over the latest lamentable rehash of Sitchin. So much more fun. Apologies for the digression.

The importance given to the severing of the skull is interesting. That corresponds rather neatly with the ‘foolish lord’ on line 26 of The Path to Sky-End (Enki’s Journey):

26. GIZ By the beam of the moon and in a thunderbolt, the brainless skull – the size of the gap not knowing, the measure of the spreading wing not taking…

(a pause…the measure not playing.)

The skull is written SAG-KUL, given meanings ‘head’ and ‘bowl’, which I posit gives the source of our word ‘skull’. It’s also the skull of Orpheus, the great musician, another strand of the story. Together the two words have the dictionary-given meaning ‘bolt’.

KUL, according to the lexical tablets, derives from KU with UL, the ‘wave’ and thus from the same source as the breakdown of KUM, the mortar and comet – also linking it to the two major riddles mentioned here, that of the antediluvian King List and of The Path to Sky-End.

GIZ, the ‘tree’ and ‘beam’, which begins line 26, is source of Arabic ‘ges’ in the name of the Giza plateau. The Inventory Stela between the paws of the Sphinx explains:

(Khufu) He came to make a tour, in order to see the thunderbolt, which stands in the Place of the Sycamore, so named because of a great sycamore whose branches were struck when the Lord of Heaven descended upon the place of Hor-em-akhet… The figure of this god, being cut in stone, is solid, and will exist to eternity having always its face regarding the East.

(Borrowed from Magicians of the Gods, p.216 of the paperback edition).perback edition).

Then there is pillar 43 at Gobekli Tepe where the outstretched wing of the bird is balancing the stone skull ripped from the headless figure below.

And finally….. pictographic AT/AD, first syllable of Atlantis, with the given meaning ‘father’ to which I add ‘ancestor’, in some versions looks very similar to the KUM of the comet. So much to be said about it all thanks to the Mesopotamian scribes – at least five thousand years’ worth and probably much more.

Never forgetting that Odin and Odysseus both have the UD of the sun in their names. I have bookmarked the Nordic site. The subject is endless but I will stop there. Thanks.

Hello MDaines:

There appears to be a conflation of stelae. Maspero discovered the “Inventory Stele” at the Isis Temple, just East of Khufu’s Pyramid of Queen Henutsen, aka [G1c]. The “Dream Stele” resides between the paws of the Sphinx.

Dr. Troglodyte

Yes, thank you for pointing that out, Dr.T. The quote is, of course, from a section of the Inventory Stela which refers to the area where the Sphinx is located. But it was not discovered between the paws. As I’m sure you know, Graham mentions the two stelae together in relation to the controversy over the dating of the Sphinx and the unjustified rejection of the Inventory Stela in that regard by Egyptologists. The confusion over provenience is entirely mine.

Fortunately, that doesn’t affect the overall sense of my comments concerning the thunderbolt. As someone who certainly knows more of the history of Egypt than do I, do you have any thoughts on the whereabouts or existence of a great tree at Giza? Is it mentioned elsewhere to your knowledge? It was clearly noteworthy and yet there appears to be nothing more about it on the Egyptian side. From my perspective, it would have been of some importance.

The Sycamore was once known near the Pyramids at Giza:

https://grahamhancock.com/phorum/read.php?1,1087101,1088720,quote=1#REPLY

Dr. Troglodyte

On his site, Andrew Collins gives an interesting Arabic name for the sycamore: el-gomez. But I don’t find it elsewhere.

The surname Gomez from Portuguese: Gomo + -es (“son of”).

Middle English ‘gome’ from Old English ‘goma’ (man, lord, hero) from proto-Germanic ‘gumô’, man. (wordsense.eu) So perhaps somewhere along the line: ‘son of the lord’ and link to ‘gum/kum’?

Swahili ‘gome’ with the meaning ‘bark’ of a tree, probably taking us back to the ‘gum’ that is rubber and not obviously connected to the sycamore. Along with Malay, this language has so far yielded one or two surprisingly close links to Sumerian.

Sycamore wood was used to encase Egyptian mummies at some point. – something that might relate to the story of Osiris enclosed in the roofbeam of the King of Byblos and to wood destroyed by a thunderbolt:

“As they relate, Isis proceeded to her son Horus, who was being reared in Buto, and bestowed the chest in a place well out of the way ; but Typhon, who was hunting by night in the light of the moon, happened upon it. Recognizing the body he divided it into fourteen parts”

(Isis and Osiris, Plutarch).

Apparently, the tree can grow to great heights and its trunk become extremely broad, sometimes hollowed out, giving both shade and a hiding place. Also the sycamore was said to be sacred to Hathor but a quick search throws up no reference to an Egyptian or Greek text on that subject. I would love to know if there exist other early textual sources for any of the above.