People have speculated endlessly about the whereabouts of the Garden of Eden. Was it in Armenia? Turkey? The Middle East? Location, location, location. The Kolbrin tells it differently – and Yvonne Whiteman tries to unravel the puzzle.

The Kolbrin‘s first Egyptian book, the Book of Creation, contains a story set somewhere called ‘the Gardenplace’. Reading it, you’ll find yourself thinking of the more familiar Garden of Eden story. This is where The Kolbrin says the Gardenplace was (text courtesy of The Culdian Trust (http://culdiantrust.org)):

‘When the Earth was young and the race of man still as children, there were fertile green pastures in the lands where all is now sand and barren wasteland. In the midst of it was a gardenland which lay against the edge of the Earth, eastward towards the sunrising, and it was called Meruah, meaning The Place of The Garden on the Plain. It lay at the foot of a mountain which was cleft at its rising, and out of it flowed the river of Tardana which watered the plain. From the mountain, on the other side, ran the river Kal which watered the plain through the land of Kaledan. The river Nara flowed westward and then turned back to flow around the gardenland.

‘It was a fertile place, for out of the ground grew every kind of tree that was good for food and every tree that was pleasant to the sight. Every herb that could be eaten and every herb that flowered was there. The Tree of Life, which was called Glasir, having leaves of gold and copper, was within the Sacred Enclosure. There, too, was the Great Tree of Wisdom bearing the fruits of knowledge granting the choice and ability to know the true from the false. It is the same tree which can be read as men read a book. There also was the Tree of Trespass beneath which grew the Lotus of Rapture, and in the centre was The Place of Power where God made His presence known.’

Since first I picked up a copy of The Kolbrin (if the name is new to you, see my earlier article, ‘Guide to the Kolbrin’), curiosity has drawn me endlessly to this description. Because it is set out so matter-of-factly, it’s possible to draw up a list of topographical pointers:

It was a place where all is now sand and barren wasteland. (This suggests dramatic geological/climate change in a past so remote that ‘the Earth was young and the race of man still as children’).

It was eastward towards the sunrising (looking eastward from Egypt).

It lay at the foot of a mountain which was cleft at its rising.

The Tardana River flowed out of it and watered the plain.

On the other side of the mountain the River Kal watered the plain through the land of Kaledan.

The River Nara flowed westward, then turned back to flow around the gardenland.

The bad news is that (as always in The Kolbrin), most of the names are skewed and there are no chronological dates. The good news is that, while civilisations may rise and fall and rulers topple, place-names tend to endure over time. So a couple of years ago I set out with some books and my trusty search engine to see what I could find in the most likely locations ̶ the Fertile Crescent, Armenia, Bahrain. But I couldn’t crack it. The description remained stubbornly obscure.

MERUAH

A few months ago, I noticed in my Atlas of Mesopotamia that one of the places the Sumerians traded with was called Melujja (Akkadian). This sounded a bit like ‘Meruah’, so I googled it with lots of different spellings – and got nowhere. Then I read Andrew Collins’ Gobekli Tepe: Genesis of the Gods, in which the author enthusiastically speculates that Eden was in the Mush area of Turkey. Once again I turned to the Kolbrin text ̶ until I realised that Turkey is not east of Egypt. But surely, I thought, no-one would have made up names like Meruah, Tardana, Kaledan, Nara, and a mountain cleft at its rising – would they?

I was ploughing through a series of essays entitled Mysteries of the Ancient Past when I read that a group of ancient people flooded out of their homeland of Sundaland in south-east Asia eventually ended up ‘at Merhgarh in what is now Pakistan’. Merhgarh? Now, that sounded a bit like ‘Meruah’. I googled it, and this is what I found:

‘Mehrgarh (Balochi: Merhgaŕh … sometimes anglicised as Mehergarh or Merhgar) is a Neolithic site located near the Bolan Pass on the Kacchi Plain of Balochistan, Pakistan, to the west of the Indus River valley.’

…

‘Evidence has been found suggesting that a civilization existed in Mehrgarh as early as 7000 BCE which is 3500 years before the Indus Civilization.’

…

‘Mergarh is one of the earliest sites with evidence of farming (wheat and barley) and herding (cattle, sheep and goats) in South Asia.’

…

‘The archaeological site of Mergarh covers nearly 300 hectares… Houses were made of rectangular mud bricks and laid out systematically. There is evidence of domestication of animals and a land less arid than it is today. In the roughly 360 graves that were excavated there were utilitarian objects and the ‘luxurious’ secured through trade, such as shell, lapis, turquoise and steatite.’

…

‘Stone age people in Pakistan were using dental drills made of flint 9,000 years ago, according to researchers. Teeth from a Neolithic graveyard in Mehgarh in the country’s Baluchistan province show clear signs of drilling. Analysis of the teeth shows prehistoric dentists had a go at curing toothache with drills made from flint heads.’

…

‘The archaeological site, which lies between the present-day cities of Quetta, Kalat and Sibi in Baluchistan, was destroyed in 2001. The tribal heirs of the area, the Raisanis, were displaced by Yar Mohammed Rind supported by Pakistani forces after they refused to support the military establishment headed by the dictator Pervez Musharaf.’

Graham Hancock has written in some depth about Merhgarh/the Indus Valley/rising seas and melting ice-caps in his book Underworld.

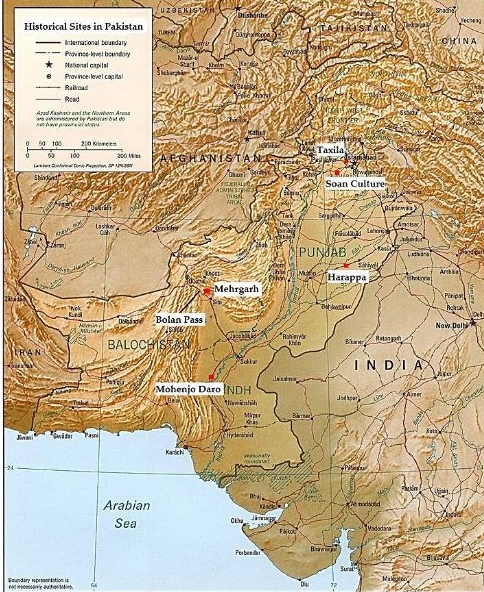

Below is a map showing Merhgarh and the more well-known Indus Valley sites of Mohenjo Daro and Harappa (both emerged around 2600 BC). A Google Earth photo shows what a scrubby wilderness Merhgarh is these days.

(CC): wikipedia

Source: Google Maps

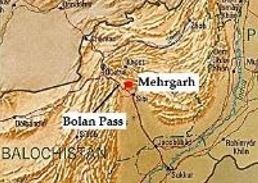

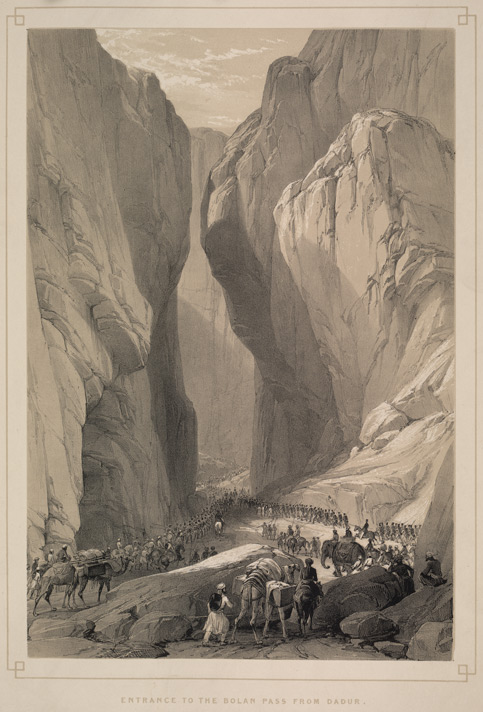

AT THE FOOT OF A MOUNTAIN THAT WAS CLEFT AT ITS RISING

Merhgarh sounded a good place to start. But what was the Bolan Pass? I vaguely recognised the name. Wikipedia describes it as a mountain pass through the Toba Kakar mountain range of Balochistan 120 kilometres from the Afghanistan border, connecting Sibi with Quetta by road and railway. The pass itself is made up of a number of narrow gorges and stretches 89 km, with the Bolan River flowing through it. During the Raj, the British fought campaigns there and built a railway (ah, that was what I remembered). Elsewhere I read, ‘A route along the banks of the Bolan River has been used for thousands of years by traders, invaders, and nomadic tribes between India and higher Asia.’

On the map, the pass appears as a thin reddish line running from north-west to south-east with a big brown mass of mountain rising on each side ̶ see map below with an old print showing part of the pass. Could this be ‘the mountain cleft at its rising’?

(CC): source

TARDANA

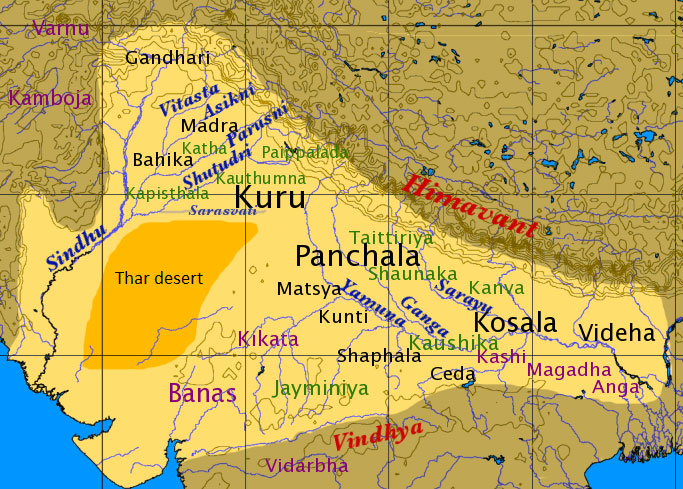

I couldn’t find a river called ‘Tardana’ on the map. There’s just desert – the Great Indian Desert which forms a natural boundary between India and Pakistan. And then, on a map of Vedic India, I noticed written across the plain its traditional name ̶ the Thar Desert.

This was promising. But, if ‘Tar’ was Thar, what did ‘dana’ mean? More searching established that in Sanskrit the word means ‘gift’ or ‘generosity’. Could Tar-dana = ‘Generosity of Thar’?

Then why is the Thar a desert? Why is there no Tardana River flowing generously through the landscape now? The Rig Veda, an extremely ancient collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns composed in India 1700-1100 BC, speaks of a great river called the Sarasvati that flowed through the Indus Valley in ancient times. Recently the French archaeologist Henri-Paul Francfort used images from the French satellite SPOT to establish that the Sarasvati started to dry up in the middle of the 4th millennium BC and gradually disappeared. These days there is still a waterway of sorts through the Thar Desert, but it is not the bountiful Sarasvati flowing from the Himalayas: this one, called the Ghaggar-Hakra, only appears intermittently during the monsoon season.

Satellite photography and ongoing research shows that the Ghaggar-Hakra was once a huge river ̶ the ancient Hakra river bed was between three and ten kilometres wide. This great river system once ran along the entire submontane region of the northern/northeastern Himalaya and drained into the Arabian Sea, carrying the combined discharge of the Indus, Ganga and Brahmaputra rivers. The Sutlej river and perhaps the Yamuna river too flowed into the Ghaggar-Hakra river bed, and have changed their courses several times. Earthquakes probably caused the river to disappear and redirected its tributaries (more on this at the end Gardenplace story below). There is even paleobotanical evidence for the aridity that developed after the river dried up.

FROM THE MOUNTAIN, ON THE OTHER SIDE, RAN THE RIVER KAL WHICH WATERED THE PLAIN THROUGH THE LAND OF KALEDAN

Looking up towards what The Kolbrin describes as the ‘other side’ of the mountain, north-east of the Toba Kakar mountain range lies a town called Kalabagh on the banks of the Indus River ̶ see marker on map below. The name ‘Kalabagh’ has a Turkic/Persian origin, meaning ‘garden village’. Herodotus, the 5th-century BC Greek historian, mentions an area stretching ‘from Kalabagh to the sea’ whose inhabitants had never been subject to King Darius of Persia. Kalabagh’s hills are mentioned in the legends of Buddha. There is a Kalabagh Plain south of Kalabagh town. This suggests that Kalabagh must once have been rather more than a town on a river-bank.

280 miles / 460 km away in Rajasthan lies the town of Kalibangan on the banks of the Ghaggar-Hakra River. The 19th-century Indologist Luigi Tessitori’s report on the prehistoric site of Kalibangan (Archaeological Survey of India, 2003) concluded that it was ‘antecedent Harappan’ and a major provincial capital of the Indus Valley civilization, with unique fire altars and the world’s earliest ploughed field. It was destroyed by earthquakes, abandoned in about 2600 BC and later resettled.

Both the towns of Kalabagh and Kalibangan are in the right area, both have names which could have become skewed to ‘Kaledan’, both are on rivers ̶ so the land somewhere between them on the Indus Plain might well have been the land of Kaledan.

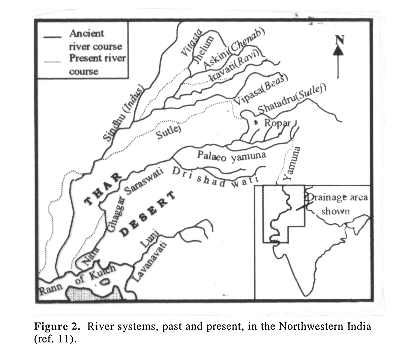

NARA RIVER

‘Nara’ is easy to place. It is the old name for the existing Nari River on the Indus plain. The ancient river system which disappeared is often referred to as ‘the Nara-Nadi system’. The map below shows past and present rivers of Indus – and the Nara River is right there among them. The map also shows the Nara flowing westward before turning back to flow around what would have been the Gardenland area.

Source: The World of Ancient Art: http://www.waa.ox.ac.uk/XDB/tours/indus3.asp

Putting all these names together, what do we get?

Meruah, ‘The Place of the Garden on the Plain’ = Merhgarh.

‘At the foot of a mountain that was cleft at its rising’ = the Bolan Pass in the Toba Kakar mountain range.

Tardana ‘which watered the plain’ = the mighty Thar river system which is known to have changed its course and dried up, leaving a desert called Thar.

River Nara which ‘flowed westward and then turned back to flow around the Gardenland’ = the ancient River Nari.

The river Kal ‘which watered the plain through the land of Kaledan’ = now the Indus River/Kalabagh or the Ghaggar-Hakra River/Kalibangan, or land between the two.

According to Hindu and Buddhist mythology, humankind originated on Mount Meru, which had parks, woodlands and groves of wish-granting trees; the river Ganges flowed down from heaven on to the summit of Mount Meru and thence to the surrounding worlds in four streams; the rulers of the four quarters of the world occupied the corresponding faces of the mountain, which consisted of gold and gems; its summit was the home of Brahma and a meeting-place of the gods. At that time, so the legend goes, there were two suns and two moons. Intriguingly, The Kolbrin says that early on in its history Earth was utterly destroyed by fire, then recreated, and in its new form ‘the sun was not as it had been and a moon had been taken away‘. There is a Mount Meru in India, up in the Himalayas north-east of the Indus Valley.

TWO OTHER PLACE-NAMES IN THE GARDENPLACE STORY

Later on in its story the Kolbrin text says:

Outside the Sacred Enclosure, known as Gisar, but forming a gateway into it was a circular structure of stones called Gilgal, and within this was a shrine.

Is it just coincidence that further north in Gilgit-Baltistan, above Jammu and Kashmir, a river called the Gilgit -̶ also known as the Ghizar/Ghizer ̶ flows past a town called Gilgit? We can only speculate why such similar names exist.

THE END OF THE GARDENPLACE STORY.

The Kolbrin’s story differs dramatically from the Genesis version and is far too long and complex to be included here. But since I’m tracking down locations, I shall jump to the story’s finale.

The Children of God were driven out of the gardenland by Spiritbeings, and then guardians were set at its gates so none could re-enter. Then it was withdrawn beyond the misty veil, the waters ceased to flow and the fertility departed, only a wilderness remained. The Children of God went to dwell in the land of Amanigel, which is beyond the mountains of Mashur by the sea of Dalemuna.

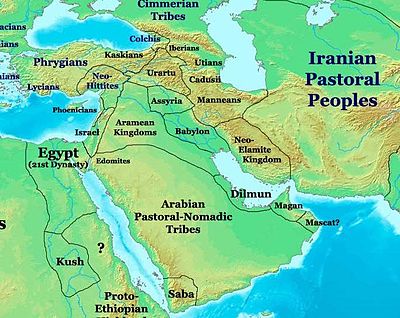

At this point, one can easily be sidetracked by mythology. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Mount Mashu was a twin-peaked mountain which the hero Gilgamesh had to pass through to reach Dilmun; it is usually identified with the Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon mountain ranges. Dilmun/Telmun was the name of an ancient civilization (3rd millennium BC) on a trade route between Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley, now identified by many with Bahrain. It is possible that these mythical names are the ‘Mountains of Mashur’ and ‘Dalemuna’ mentioned in The Kolbrin. However, I am trying to pin down the names geographically. If you’re travelling from the Indus Valley, ‘beyond the mountains of Mashur’ means you’re going west. This is what I’ve come up with:

THE LAND OF AMANIGEL

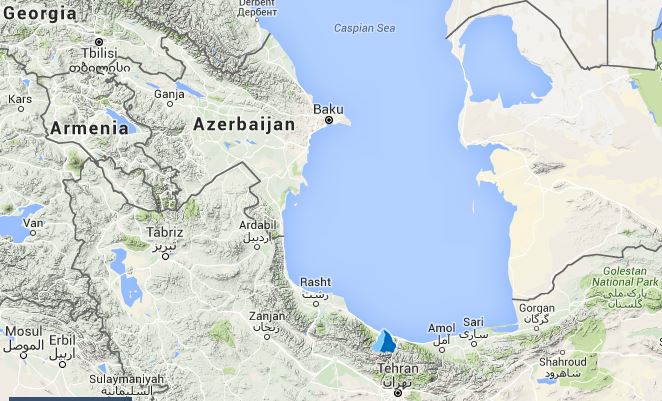

The Mannaeans were an ancient people who lived south of the Caspian Sea in 10-7th centuries BC. The map below shows their territory. Could ‘Amanigel’ refer to their land?

MOUNTAINS OF MASHUR

Kuj-e Mashur/ Mash’oor is a 13,064 ft/3,982m mountain north-west of Tehran and south of the Caspian Sea. On the map below, a small blue triangle indicates the Mashur peak.

Source: peakery.com, http://peakery.com/kuh-e-mashur-iran/

©Kogo, Source

BY THE SEA OF DALEMUNA

In its chequered past, the Caspian Sea has been given many names – Sea of Qazvin, Bahr Gilan, Kaspiyskoye, to name but a few. I can only speculate that long, long ago it might have been named after a large nearby settlement called ‘Dalemuna’. But is there a ‘Dalemuna’ near the sea? As it happens, there are three places in a westward direction within 800 km of the Kuh-e Mashur Mountains sounding like ‘Dalemuna’. The most promising falls within Mannean territory and lies about 200 km north-west of Kuh-e Mashur. It is called Deyliman / Deylamān / Dailimān / Dil’man – see map below.

Two more remote possibilities, not in Mannean territory, are Dilman in Azerbaijan, north-west of Baku on the western shore of the Caspian Sea – see map below:

and a city once known as Delemon / Dīlmagān / Dīlman / Shahpoor / Shāhpūr / Shapur, mentioned in 12th-century Christian Church records and now called Salmas / Salamas, north-west of Lake Urmia – see map below.

So, after the Indus Valley became uninhabitable, it looks as though The Kolbrin‘s Children of God moved west and settled in northern Mesopotamia, taking their knowledge of agriculture and animal husbandry with them. Archaeological discoveries in northern India suggest that the Indus civilization dates back far earlier than was previously thought, predating even the Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilisations -see Nature – Scientific Reports 6, Article number: 26555 (25 May 2016) and a covering article in the Daily Mail:

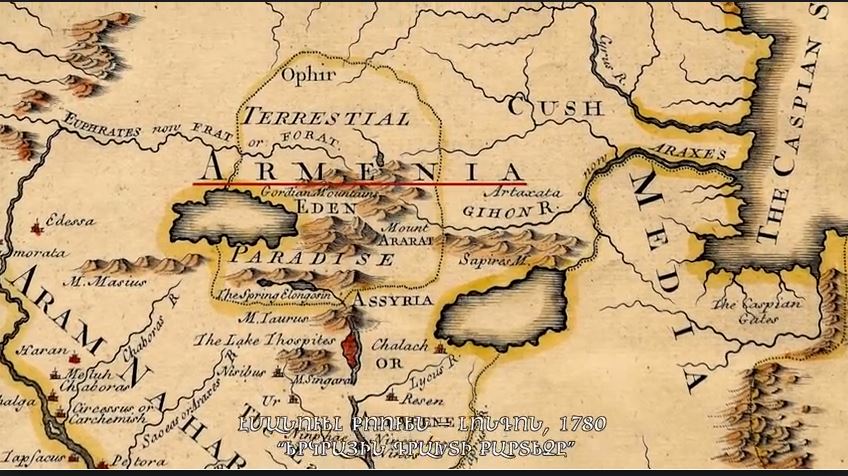

This part of Mesopotamia is stuffed with ancient Biblical associations and new discoveries: Mount Cudi, now thought to be the true landing-place for Noah’s Ark by many historians, by travel writer Gertrude Bell, and by The Kolbrin (which says, ‘the great ship came to rest upon Kardo, in the mountains of Ashtar, against Nishim in The Land of God‘); Mount Ararat, the traditional Biblical landing-place for Noah’s Ark; the Tigris, Euphrates and Gihon rivers mentioned in the Biblical description of Eden; an area near Lake Van thought to have been the Garden of Eden; Ur, traditionally the home city of Abraham; and the recently-excavated site of Gobekli Tepe.

KOLBRIN VERSUS GENESIS – OR BOTH?

How does the Book of Genesis location compare with The Kolbrin‘s Gardenplace? It reads:

‘And a river went out of Eden to water the garden; and from thence it was parted, and became into four heads.

The name of the first is Pison: that is it which compasseth the whole land of Havilah, where there is gold;

And the gold of that land is good: there is bdellium and the onyx stone.

And the name of the second river is Gihon: the same is it that compasseth the whole land of Ethiopia.

And the name of the third river is Hiddekel: that is it which goeth toward the east of Assyria. And the fourth river is Euphrates.’

Havilah and Ethiopia and Assyria are all mentioned within a vast river system. Jewish scholars tend to equate Havilah with India because in ancient times large amounts of gold came from there. (Gold has been rediscovered in the Chagai area of Balochistan, which is also a traditional source of onyx; as for bdellium, the 2nd-century AD Periplus of the Erythraean Sea states that bdellium was once exported from the port of Barbarice at the mouth of the Indus River.)

Jewish scholars also refer to the 1st-century Romano-Jewish historian Titus Flavius Josephus, who wrote of Eden: ‘the garden was watered by one river, which ran round about the whole earth, and was parted into four parts. And Phison, which denotes a multitude, running into India, makes its exit into the sea, and is by the Greeks called Ganges.‘ By ‘the whole earth’, did Josephus mean a single huge land mass? Was this the supercontinent which broke apart millions of years ago? If we take the Old Testament at face value, then this part of the world must have geologically altered on a monumental scale in the dim distant past.

There are other differences between Genesis and The Kolbrin:

In Genesis, the text jumps immediately from man’s creation to the moment when God puts Adam in the Garden of Eden. The Kolbrin says it differently: ‘Because he walked with God he was culled out from his kind and brought to Meruah, The Gardenplace. He came to it across the mountains and wastelands, arriving after many days journeying.’ He (The Kolbrin calls him Fanvar) is described as being one of ‘the Children of God’.

In Genesis, God sends Adam into a deep sleep and then creates Eve. In The Kolbrin, Adam/Fanvar first sees Eve (The Kolbrin calls her Aruah) in a vision and keeps catching sight of her in the garden, but at that point she is ‘not substantial’: she is ‘a wraith, an ethereal being … a woman, but one such as [he] had never seen before…’ In other words, Adam/Fanvar has seen women before; there were clearly men and women of various kinds on Earth before the events of the Gardenplace occurred.

In Genesis it says that God ‘drove out the man; and he placed at the east of the garden of Eden Cherubims, and a flaming sword which turned every way, to keep the way of the tree of life.’

The Kolbrin says:

Those with Dadam [Adam/Fanvar’s great-great-grandson], who looked back towards the place of the garden, saw bright tongues of light licking the sky above it, the whole being interwoven with flickering flames in many hues. Those who sought to return were repulsed with a tingling ache over their bodies which increased into severe pain as they approached, so they were driven away.

This is a classic description of lights and flames seen in the sky before a big earthquake, and of earthquake ‘sensitives’ experiencing pain before the event – as these links show.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9ZPm97HABL8

To sum up, the Genesis narrative, although it names the rivers flowing out of Eden, is a bit hazy about the Garden’s precise location, and its story goes in leaps and bounds. The Kolbrin mentions a specific location in the Indus Valley and includes more revealing narrative detail.

All of which begs the question: how old is the The Kolbrin? If the Genesis story was recorded later (orthodox rabbis say it was written around 1300 BC), could memories of the Garden’s precise whereabouts have dimmed? Who, after all, would remember the location of a garden which for thousands of years had been nothing but desert, or of rivers which had disappeared/changed course and become mythical?

Although it is tempting to put the stories side by side and fit the Children of God into the snake-and-apple scenario of Genesis, The Kolbrin‘s narrative is about something else: genetic change. And it is so extraordinary and, I suspect, recorded so much earlier, that I wonder whether ̶ as with most events beyond our human understanding – memories might have faded or toned the events down over the millennia to the Garden of Eden story we now read in Genesis.

Interesting. i’m reading Hamlet’s Mill right now after reading about it in one of your books and it seems like most myths originate with the Hindu mythology, Krishna, the mill with the blue gods, etc.

I had no idea that the Gardenplace was going to turn up in the Indus Valley. I haven’t looked at my copy of Hamlet’s Mill for about 30 years, but after what you say, I shall have to take another look.

A good read again, Yvonne. You can find Edin/Eden on the electronic Pennslyvanian Sumerian Dictionary (ePSD). It is translated there to plain/steppe/open country. Interestingly, the pictographic symbol has survived from the URUK III period, 3200-3000 BCE. See it on the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI) site, reference P471688, click on the drawing of the tablet, see the symbol twice, fourth column across, third and fourth down. The rounded part at the bottom is independently the sign KI, a suffix designating a place.

Turn clockwise 45 degrees to view as it would have been drawn originally.

Thank you for this. I’ve turned it 45 degrees – but it’s still cryptic!

Well, it is proven to be over 5000 years old here and, in my view, is a copy of a copy of a much more ancient symbol! At least,we get a general idea of the possible form on a map that the place might have had. Also, it shows how long ago Eden was known. Turning it sideways merely gives an idea of the direction in which the original symbol would have been drawn but, for a map, that’s important.

Hi all. The strongest clue to where Eden was situated was described in the bible. It was some where around Iraq!

at last Western civilization beginning to realize where cradle of civilization began

Regarding Tar-dana, the suffix ‘dan’ is present in slavic languages, for example the name Bogdan – ‘god given’ or ‘gift of god’.

Interestingly the sound ‘dn’ is found in the major rivers flowing into the Black Sea -Danube, Don, Dniestr, Dniepr; and the Turkish for word for sea is ‘deniz’