Note from the Author:

The enigmatic Kolbrin contains, alongside its Celtic records, six ancient Egyptian books, the remnants of scrolls written or copied by scribes from much earlier writings, whose provenance has not yet been proven. Most people dismiss the books as forgeries. I am convinced that their core material is genuine.

If you’re looking for atmosphere, Tell el-Amarna in Middle Egypt is the place to go. Its vast, near-deserted plain ringed by a crescent of bleak cliffs is surely what Percy Bysshe Shelley had in mind for the brooding finale of his poem Ozymandias:

‘…boundless and bare/ The lone and level sands stretch far away.’i

I went to Tell el-Amarna recently and saw, amidst razed sites and cliff tombs, the remains of a site. Photo: YW.

I went to Tell el-Amarna recently and saw, amidst other ruins and tombs, the razed remains of a site known simply as the North Palace. Looking out over the flattened area, I couldn’t help noticing its three-part layout and, as the guide indicated an area which was once an altar room, it dawned on me that this might well be the ‘residential temple’ that takes centre stage in the dramatic account of King Akhnaten found in the Kolbrin’s Book of Manuscripts. The temple description is a precise one and its meaning had always proved elusive.

My earlier article The Kolbrin’s King Akhenaten Story, published on this website 18th May 2016, set out to show how much the Kolbrin narrative adds to what has been pieced together by mainstream historians, and how recent medical discoveries are backing up parts of the Kolbrin version.ii iii iv In both records the main events are the same: the 18th Dynasty King Akhenaten (he is called Nabihaton in the Kolbrin) changed Egypt’s religion from the worship of Amun and his many gods to the single power of the sun Aten; Akhenaten left Thebes and built a new city, Tell el-Amarna, dedicated to the Aten; after his death the city was torn down and Egypt reverted to the worship of Amun.

No wonder so many books have been written about Akhenaten: his story is mystifying.

Back to that enigmatic Kolbrin description. It reads:

‘Within the City of the Horizon at Dawning was the Temple of the Sun’s Dawning, at which Nabihaton [a skewed version of Akhenaten] officiated as High Priest, but after his return with Hepoa he built a residential temple upriverwards, called “The Sun’s Blessing”. Some men have called it “The Temple of the Blessing of Light”. This was erected in three courts, one of which was called “Nefare’s Memory,” a place dedicated to womanly virtues. There, when she came of age, his daughter by Nefare, a maiden called Meriten, was consecrated in service.’v

Here is the same description matched, phrase by phrase, with what is known about the North Palace site.

‘City of the Horizon at Dawning’

From inscriptions it is known that Akhenaten’s city was called ‘The City of the Horizon’,vi which virtually matches the Kolbrin’s ‘City of the Horizon at Dawning’.

‘The Temple of the Sun’s Dawning’

Amarna had two central temples. Archaeologists call them the Great Aten Temple and the Small Aten Temple.vii The Kolbrin is probably referring to the bigger temple where the king officiated.viii

‘Upriverwards’

The North Palace site is located north of the city of Amarna. The Amarna Project website describes it as standing ‘between the North Suburb and the North City, facing west towards the river and standing perpendicularly on a line a little back from the prolongation of Royal Road’.ix

Simplified map of Amarna showing North Palace (here called Northern Palace) at the top. Source.

‘A Residential Temple’

Unusually, the structure known to historians as the North Palace was built containing both residential accommodation and an altar court with an offering place. ‘Its east-west alignment and axial symmetry have drawn the comment that it resembles a temple as much as a palace,’x writes Barry Kemp, who spent 30 years excavating the site. The words ‘residential’ and ‘temple’ make strange bedfellows, and since this residential temple was to play such a part in the downfall of its builder and his dream city, it could equally well be called a folly.

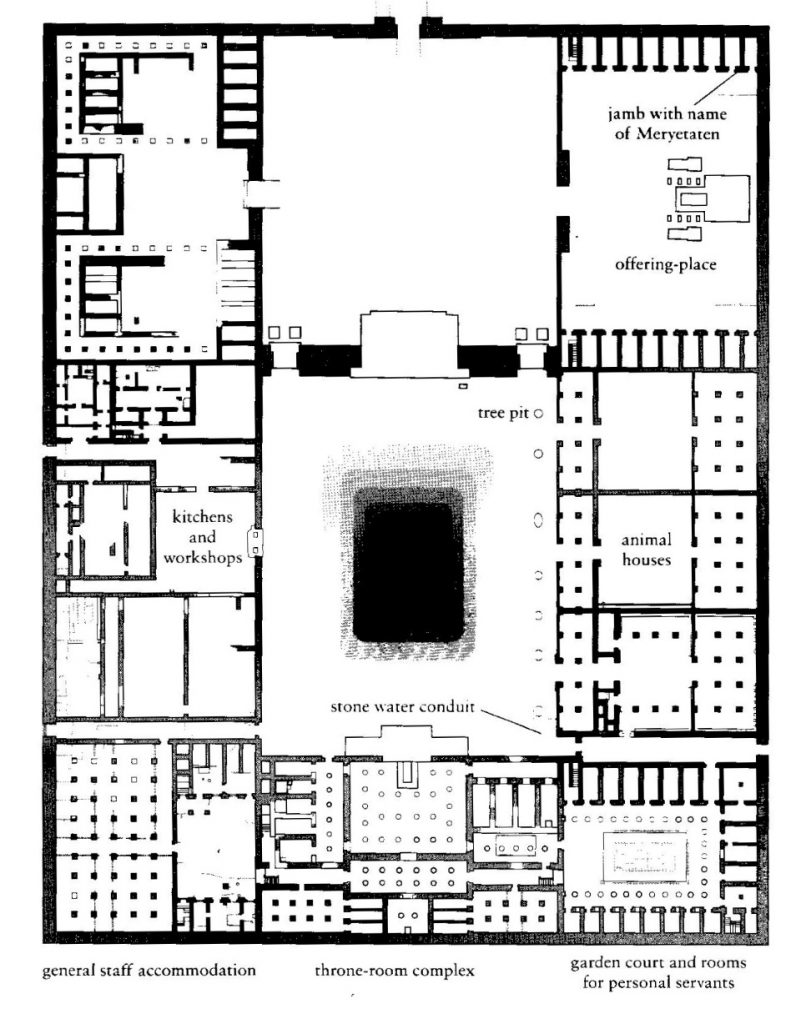

Plan of the North Palace showing residential quarters, chapel and offering-place, jamb inscribed with Meritaten’s name, central pool, workshops, kitchens and animal houses. Photo: B. Kemp.

‘Erected in Three Courts’

The three courts can clearly be seen forming three sides of a rectangle in the ground plan above. Nowhere else in Amarna is there a structure built with three courts like this.

One of Which Was Called “Nefare’s Memory”’

Current thinking has it that the North Palace site was associated not with Akhenaten’s Great Royal Wife Nefertiti, but with his mysterious wife Kiya and later, with his second daughter Meritaten, who eventually became his ‘Great Royal Wife’.xi No inscriptions have been found here or anywhere in Egypt referring to Nefertiti in the later part of his reign, and historians have no idea why her name disappeared.

But the Kolbrin tells us why. It says that in the fifteenth year of Akhenaten/Nabihaton’s reign, his Great Royal Wife Nefertiti (the Kolbrin calls her Nefare) formally moved out of Amarna (‘The queen removed herself and her household in the fifteenth year of the reign of Nabihaton…)xii Akhenaten’s reign is recorded as lasting just seventeen years (from 1353-36 or 1351-34 BC), so according to this reckoning, Nefertiti left him in the mid-1330s BC.

Why did she leave? Quite simply, says the Kolbrin, because of the way he behaved. Akhenaten/Nabihaton had

‘unnatural longings, which he lacked the strength to control and subdue… strange rumours were heard about him in the streets and marketplaces’.xiii

Most readers would take this to mean that Akhenaten went with rent boys or prostitutes, or perhaps had paedophilic tastes. He ‘inclined away from the highborn ladies of royal blood, his interests were not those of a Pharaoh…’ xiv

None of this would have been apparent to the Egyptian people: the Kolbrin says that publicly ‘the marriage appeared successful enough, though perhaps the outward display of affection was overdone.’xvAkhenaten and his family are always pictured as the epitome of togetherness. Were the painted and carved displays of affection we see on museum and boundary walls overdone—or even used as propaganda—as the Kolbrin suggests? Barry Kemp notes that the family’s homes were widely dispersed (see map), and ‘One is left wondering to what extent the royal family did live and move as a single unit.’xvi

The Kolbrin goes on:

‘Nefare despised the king in her heart for his secret wickedness… [she] could not dwell with Pharaoh while the life he led was an abomination against purity… The queen removed herself and her household… (she) sought refuge in Lebados [a skewed version of Abydos?—centre of the Isis and Osiris cult] where there was a secret shrine to The Great God, and resigned herself to a life of great virtue.’xvii

The Kolbrin scribe adds,

‘It was then put about, by those who licked the feet of Pharaoh, that she was a fickle woman of wanton ways. They said she was an adulteress and called upon her beauty to bear witness against her.’xviii

Later, the Kolbrin refers to ‘Neferuten’ [a skewed version of Neferneferuaten?— the name of the queen thought to have ruled for a short while after Akhenaten’s death]. She is described as the ‘wife of Upofa’ [I have no idea who Upofa was]. The scribe comments,

‘Neferuten was, of all women, the most virtuous; yet surely no woman ever evoked such malice in the hearts of her sisters!’xix

—which suggests that ‘Nefare’ and ‘Neferuten’ might have been one and the same person.

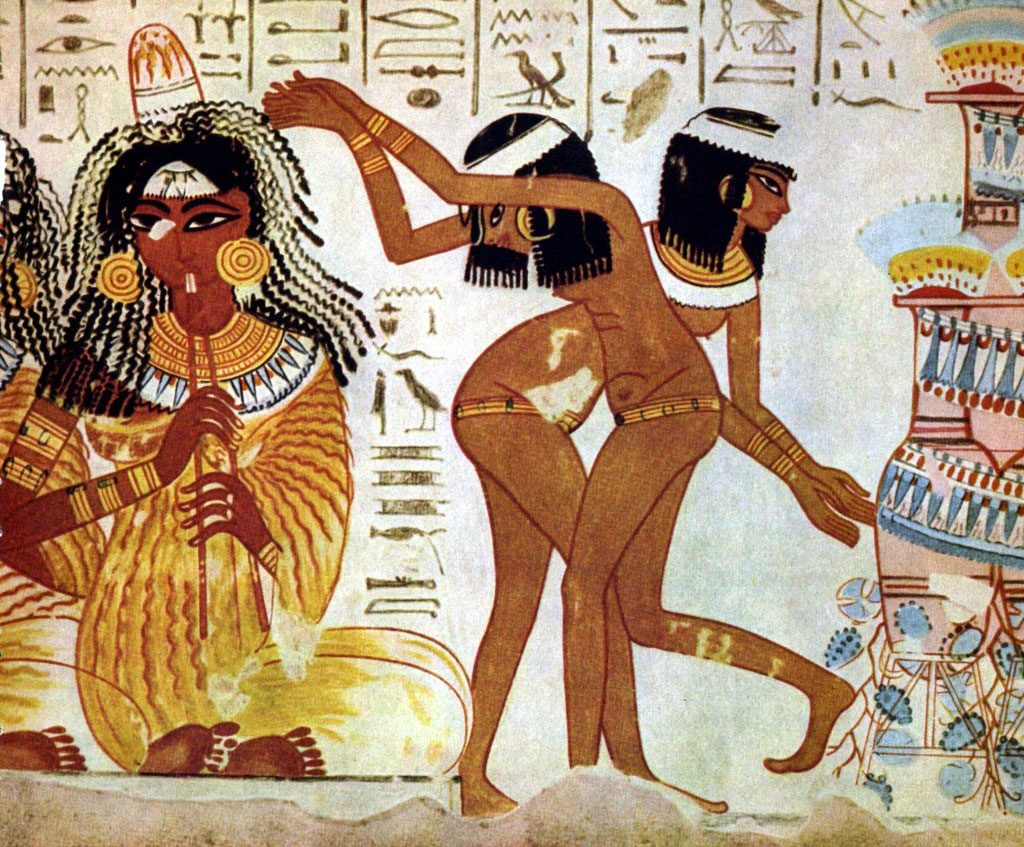

The Kolbrin’s Book of Manuscripts has much to say about Akhenaten/Nabihaton’s other wife whose identity has always baffled historians. It does not give her name, but speaks of the pharaoh’s ‘interest in the Mistress of Songstresses at the Temple of Amon in Victory’, and says she had a son by him—a son of whose existence Akhenaten was unaware and whose early history carries an echo of the Old Testament childhood Moses story. I identify this woman with Kiya—named on inscriptions as ‘Greatly Beloved Wife of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt’.xx Her unusual name suggests she was foreign by birth. Large earrings on the unfinished head below hint that she might have been a dancer.xxi

By Richard Mortel – Unfinished head of Kiya from Amarna, 18th dynasty, ca. 1345-40 BCE; Pergamon Museum, Berlin, CC BY 2.0

Musicians and dancers on fresco at Tomb of Nebamun, showing large earrings; British Museum [Public domain].

When Nefertiti left, Akhenaten was left with just his daughters and his memories—hence a court in the palace named ‘Nefare’s Memory’. Locals have always called the place Kasr Nefertiti, meaning ‘The Palace of Nefertiti’, which suggests that traditionally it was linked with Nefertiti/Nefare.xxii

‘A Place Dedicated to Womanly Virtues’

Archaeology has revealed that the North Court of the Residential Palace contained housing for different kinds of animals— but ‘the numbers of animals provided for seem excessive’.xxiii Could some of the animals have been there just for ornament? On the south side, ‘the… space was filled with what look like service buildings: houses, probably a bakery, and kilns where perhaps faience jewellery was produced’.xxiv

This was surely ‘the place dedicated to womanly virtues’. It brings to mind the Hameau de la Reine – the 18th-century rustic folly built for Marie Antoinette at the Palace of Versailles which contained a vanity farmhouse producing milk and eggs for the queen, a dairy and a dovecote decorated with gardens and orchards.xxv

The Kolbrin continues:

‘There, when she came of age, his daughter by Nefare, a maiden called Meriten, was consecrated in service.’

As the ground plan shows, the palace contained a chapel with altars for offerings. Barry Kemp writes, ‘Many inscriptions show that it belonged to Merytaten; her name can still be seen inscribed on one of the Sun Chapel’s door jambs, carved over an earlier name’xxvi (see photo below).

Inscription with Meritaten’s name found on door jamb in the Sun Chapel. Photo: Courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society.

Another temple south of Amarna, a garden temple called Maru-Aten, is associated with Meritaten through its inscriptions, but it does not have the three-court structure which makes the North Palace so distinctive.

It is not known when girls came of age in Ancient Egypt – perhaps at puberty.

It is clear from the above matches that the Kolbrin is describing what historians call the North Palace. So from the Kolbrin we now know its original name: ‘The Sun’s Blessing’ or ‘The Temple of the Blessing of Light’.xxvii

Why was Aknenaten Wiped Out of Egypt’s History?

Anyone seeing the great spreading plain of Amarna razed to the ground and his name obliterated cannot help but think, as I did, ‘How people must have hated Akhenaten!’ But why? The Kolbrin gives several answers:

Firstly, the rich, powerful priests of Amun loathed their Pharaoh because financially, he bled them dry to build his dream. The Kolbrin speaks of ‘hostility by the priests of Amun’ who ‘were impoverished to pay for the new city’.xxviii

Secondly, Akhenaten/Nabihaton behaved in what was regarded as an extremely un-kingly fashion. To give just one example: the Book of Manuscripts says,

‘The highborn ones about him… were perturbed at his interest in the Mistress of Songstresses at the Temple of Amon in Victory. The faithful were perturbed also, for within this temple was one of their secret shrines… [they] were antagonised.’xxix

This leads to the third black mark against Akhenaten. ‘It was the wife of Pharaoh [which wife? Perhaps it was Nefertititi, since she followed the old religion of Atun, part of which was hidden from public religious practice]

who influenced him to disclose some of the mysteries which… had been completely… and very carefully hidden. Thus, though the forces of evil had prevailed in the land they had not uncovered the Inner Shrine of the Sacred Mysteries… The great secret of how to penetrate the barrier between the two spheres of mortal and spirit was still completely secured. If nothing else its very dangers would have safeguarded it.’

My previous article ‘The Kolbrin On Immortality: How Egypt Regained the Secret of the Ages’ deals with this mysterious hidden knowledge.

Fourth, despite introducing a new religion, Akhenaten himself appeared ungodly, in a land where pharaohs were worshipped as gods. The Book of Manuscripts reproduces a lengthy prayer written by the Pharaoh in which he says,

‘I who am mortally blind and mortally frail, I sought for help, but it came not. I wept, but there was none to comfort me… I who am great, have less than the least.’

Never before, says the Kolbrin, had such a prayer been offered in public by a Pharaoh, ‘and the people murmured that divinity had departed from the king’.xxx

Fifth, there was the matter of incest with his daughter Meritaten/Meriten. The Kolbrin states that

‘after the consecration of Meriten [which took place in the North Palace/The Temple of the Blessing of Light]… the eyes of Nabihaton/Akhenaten wandered towards her lustfully’,

that he

‘did take his daughter in awful wickedness, his evil thoughts displaying themselves uncontrollably… Throughout the new city he caused the name of Nefare [Nefertiti] to be struck out and the name of Meriten was put in its place.’xxxi

Head of Meritaten, The Louvre. CC BY-SA 4.0

Since Meritaten/Meriten is thought to have been born c.1356 BC, her mother Nefertiti/Nefare would probably have been aware of the incestuous relationship for some time before she left Akhenaten/Nabitaton.

Nicholas Reeves writes at some length about Akhenaten’s ‘unhealthy sexual interest in his children’ and of possible offspring by his daughters Meritaten, Meketaten and Ankhesenpaaten.xxxii

The Kolbrin describes this incestuous union as ‘awful wickedness’xxxiii and ‘the union of evil’xxxiv ‘Although it had been accepted that the kindred of the Pharaoh could inter-marry, any union between parent and child was absolutely forbidden. This law from days long past was still binding.’ xxxv

It emerges from the Kolbrin that Akhenaten/Nabihaton’s incestuous union with his daughter Meriten/Meritaten produced two offspring.

‘The son of Nabihaton, one conceived in wickedness, was slain in battle [I identify this son with Smenkhkare], therefore the younger son [I identify this son with Tutankhamun], one also born of the union of evil, became king in Egypt in his day.’xxxvi

It is possible that ‘conceived in wickedness’ and ‘born of the union of evil’ could refer to Akhenaten’s male offspring by daughters other than Meritaten, but the context implies that Meritaten was their mother. According to the Kolbrin, Nefertiti,

‘being more frail than Egyptian women, could bear only daughters. There is another reason for this, but it cannot be gone into here with propriety. It is something between women.’xxxvii

‘While yet young’ says the Kolbrin, ‘he [Tutankhamun]

became a follower of the new rites of mystery which his father had set up… As far as the faithful [followers of Amun] were concerned, the setting up of a new form of worship made little difference to their position in the land, but they did attempt to draw the young prince wholly within their fold…xxxviii

Archaeology confirms this with the finding that Tutankhamun started life with the name Tutankh-aten before changing it to Tutankh-amun. The Kolbrin goes on:

‘The next Pharaoh [Tutankhamun] married his sisterxxxix[his half-sister Ankhsenamun, the third of Akhenaten’s and Nefertiti’s daughters], [he was] conceived in wickedness, and therefore died while yet young…’xl

And Tutankhamun is referred to one last time as ‘Pharaoh’s short-lived successor’.’xli

Sixth and last in this lengthy list of hates: the king was physically weak. His people, who were aware that their pharaoh, ‘the Great One of Egypt, was ill-formed in body’,xlii were disturbed by Akhenaten/Nabihaton’s extreme attacks of epilepsy which started when he was a boy and continued throughout his life. The Kolbrin takes pains to describe these—his blackened tongue and his howling ‘as dogs howl so that all men departed from him in fear’xliii (for further details, see my earlier article). The Kolbrin states,

‘Though the law which decreed that any one of royal blood suffering a demon-induced deformity or becoming possessed by a Dark One should be given the draught of death, [this] was no longer enforced. This proves how evil ensues when old and trusted laws established by the wise ones of old are cast aside.’xliv

The 2014 BBC documentary ‘Tutankhamun: the truth uncovered’ (see my end-note (ii) for a link to the programme) suggests that Amenhotep III’s and his descendants’ earlier and earlier deaths, their visions and feminized bodies all resulted from Familial Temporal Epilepsy. This tallies with the Kolbrin account of Akhenaten’s condition.

Had Akhenaten been dealt with according to Ancient Egyptian tradition and given euthanasia as a child, Egypt would never have suffered the catastrophic Amarna years. As it was, says the Kolbrin, ‘Nabihaton, Pharaoh of Egypt, was a strange mixture of goodness and wickedness, both carried to their extreme’xlv and the country suffered as a result. After Akhenaten/Nabihaton’s death (details of which were uncertain even at the time, says the Kolbrin),

‘the signal was given and the people arose in the streets. The new worship… died away as the growth dies back on an onion. But like an onion, the bulb remained. The new worship… would have survived had not its founder led an impure life… To establish a pure form of worship and beliefs its founder must also be pure of hands and heart.’xlvi

A Secret History

This, then, says the Book of Manuscripts, is the secret locked into the North Palace site at Amarna. The residential temple was where, while Akhenaten and Nefertiti were to all appearances a devoted couple, Akhenaten first cast lustful eyes on his daughter Meritaten at her consecration to the god Aten in the Sun Chapel. This led to an overpowering incestuous relationship with his daughter which, after Nefertiti left him, the King made no attempt to hide, and it must have continued for some time since it resulted in the birth of two sons, Smenkhkare and Tutankhamun, who were so badly affected by hereditary medical conditions that they died young. Finally, events led to Akhenaten’s own death, disgrace and the obliteration of his precious city.

The North Palace site showing, in the middle distance, all that remains of the garden pool – Photo: YW

What a story lies in those silent stones! And to think that the Kolbrin—a mysterious set of books with no provenance—provides the key to unlock the Akhenaten story, stretching back over more than 3,300 years.

The author welcomes correspondence with readers via [email protected].

Kolbrin text courtesy of The Culdian Trust.

References

i P. B Shelley, Ozymandias (1977).

iii The Guardian, ‘Egyptian Pharoah Tutankhamum’s Wet Nurse May Have Been His Sister’ (21st September 2015).

iv AFPTV, ‘Maia, Egyptian Pharoah Tut-Ankh-Amun’s Wet Nurse, Was His Sister Merit-Aten, the Amarna Princess‘ (21st December 2015).

v The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:56.

vi B. Kemp, The City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti: Amarna and its people (Thames & Hudson, 2012).

vii Ibid.

viii Ibid.

ix Amarna Project, ‘North Palace‘.

x B. Kemp, The City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti: Amarna and its People.

xi Ibid.

xii The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:52.

xiii The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:48.

xiv The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:42.

xv The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:48.

xvi B. Kemp, The City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti: Amarna and its People.

xvii The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:52.

xviii Ibid.

xix The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:68.

xx N. Reeves, Akhenaten: Egypt’s False Prophet, (AUC Press, 2019), pp. 154-7.

xxi Ibid.

xxii J. Dunn, ‘The North Palace at Armana (Ancient Akhetaten)‘ (Tour Egypt).

xxiii B. Kemp, The City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti: Amarna and its People.

xxiv Ibid.

xxv Chateau de Versailles, ‘The Queen’s Hamlet’.

xxvi B. Kemp, The City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti: Amarna and its People.

xxvii The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:56.

xxviii The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:41.

xxix The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:43.

xxx The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:59.

xxxi The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:58.

xxxii N. Reeves, Pharaohs of the Sun: Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 1999) p. 93; N. Reeves, Akhenaten: Egypt’s False Prophet, pp. 157-9.

xxxiii The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:58.

xxxiv The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:39.

xxxv The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:61.

xxxvi The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:39.

xxxvii The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:48.

xxxviii The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts, 34:39.

xxxix The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:66.

xl Ibid.

xli The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:67.

xlii The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:38.

xliii The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:54.

xliv The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:61.

xlv The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:60.

xlvi The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 34:65.

Lovely insight, thank you.

Yvonne, sterling work in raising this book to awareness in Egyptology. Its detail seems to indicate transcription from a contemporary Egyptian, or early Hebrew, or via late Egyptian source.

Just one query, on the ‘residential temple upriverwards, named Sun’s Blessing’; upriver is on the south, since the Nile runs south to north. Was that a translation error from ‘downriver’? Or an error by a foreign author or translator looking at a map? Or was there a similar building at Maru Aten?

To begin with I scratched my head about this, but I then realised that ‘upriverwards’ breaks down into ‘up-riverwards’. ‘Up’ refers to the rising ground towards the North City, and ‘riverwards’ is used in the traditional sense of ‘by way of the river’.

Great to see you with another update on this topic Yvonne, and totally smashing work once again!

The story of AkhetAtens reign is a stern warning for all of what happens when man gives in to all his beastly needs, even if it was contrasted with great goodness.

It`s natural law in effect, and none are excempt, not even the pharoah.

Yet maybe the story is even stranger…

I don`t know if you are aware of it, but the hugely misunderstood Immanuel Velikovsky wrote this book wayback here he takes up the story about these families and what might have happened.

Reading this book back to back with the Kolbrin epic makes things much clearer,

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/632273.Oedipus_Akhnaton

On another note… The courtyard tales – what were the whispers going on? It seems the Amon priesthood were putting ut a bunch.

If you want to read something completely different and fictional, but very much in the same style, check out Sinhoue the Egyptian by finnish author nobel prize winning author Mika Waltari, it`s beautifully written novel in the same style as those old egyptian texts, and at times really hilarious, as he mixes in a good deal of the rumour mongering that the Amon priests put out to combat the new kind of worship that Akhetaten wanted to realize, in all likelyhood Mika did this based on what he had studied…

But It`s a fictional romp so it is not so important. Although, based on a real character

I am also amazed to learn about the new found mummy of Queen Tyi, which leads to speculation wheter she was from the Pharoe islands up int the North Sea.

This is not impossible, since we know of the phonecians were already sailing into the baltics harvesting amber on the shores there.

If you want to read some really amazing accounts about the nordics since the earliest recorded stories, scheck out the big tome by arctic explorer professor Fridtjoff Nansen called the Northern Mists. Including an incredible story, unrelated to this, of Pytheas from Massalia

I’ve read Velikovsky on Akhenaten but I didn’t go along with some of his ideas. And yes, I’ve read Sinuhe the Egyptian and have the DVD! Thanks for telling me about Fridjoff Nansen – I’ll look him up.

Yvonne, Thank you for your tireless dedication to bringing this “ignored” history to light. I am very impressed with your work. It sheds so much more light on what, why and how. Thank you for sharing it with those of us who care about the truth behind our lost knowledge. You are a true historian. Unlike Mr. Zahi Hawass who like to modify and mold history to fit their narrative.Thank you.