Akhenaten … Nefertiti … Tutankhamun. The names ring out amidst the gold and ruins of Ancient Egypt’s 18th Dynasty, and so high do they hit the headlines at each fresh discovery, we tend to think we know them. Well, we may know the basic facts from inscriptions, archaeology and science, but we know little about why things happened as they did. Yvonne Whiteman investigates what The Kolbrin has to say about this enigmatic Pharaoh.

© Papillus (CC BY-SA 3.0)

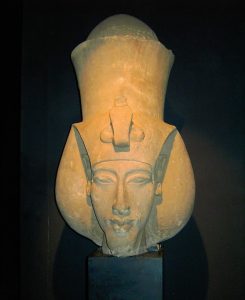

Akhenaten: he of the elongated head and feminized body, who reigned from 1353-35 B.C. He has been called a saint, a tyrant, a utopian, a rebel and an affectionate family man. Following the immensely wealthy times of his father Amenhotep III, during his 17-year reign Akhenaten turned away from his country’s age-old polytheistic beliefs under the chief deity Amun and instead imposed a monotheistic sun religion focused on the god Aten. Changing his name from Amunhotep IV to Akhn-aten, the king had the name ‘Amun’ erased on all state inscriptions, built a new capital, Amarna, and moved his court there, rewrote the textbooks and revolutionised the archaeology and art of his time (‘the Amarna period’). He composed a hymn entitled ‘Great Hymn to the Aten’ which has been compared to Psalm 104. With his wife Nefertiti he had six daughters. His legacy was wiped off the records after his death.

When his tomb was discovered in 1893-4, it was found to be empty and its images defaced (see reworked sample below). Recent genetic and other scientific tests on 15 mummies confirm that one of the individuals buried in tomb KV55 was both the son of Amenhotep III and the father of Tutankhamun, and is probably Akhenaten.

That, briefly, is what we know about this strange pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty.

<See picture here>

Buried deep in the patchwork of texts making up The Kolbrin’s Egyptian books, there exists the lengthy story of a pharaoh called Nabihaton. Anyone who already has a basic knowledge of the Pharaoh Akhenaten will soon realise that this king is none other than Akhnaten. At one point mention is made of a young princess ‘called Nefare, in our tongue’. What that tongue may be, no-one knows; The Kolbrin, published in 1994 by The Culdian Trust, has no provenance; its Egyptian books are a collection of disparate scrolls now translated into English, and all we know about Annexed Scroll 2, Book of Manuscripts is what we read in the first paragraph: that it was found ‘in the temple of Athorhara, the possession of Neyti, a free woman of Pibes’. (As everywhere else in The Kolbrin, names of people and places are skewed. ‘Athorhara’ suggests the Temple of Hathor at Dendera, while ‘Pibes’ might be Thebes.)

Anyway, I tucked the Akhnaten/Nabihaton story away, vaguely hoping that something interesting might turn up to persuade me it wasn’t just a fairy tale. And blow me down, something did.

On 20th October 2014, following Jessica Hamzelou’s 2012 New Scientist article Tutankhamun’s death and the birth of monotheism , the BBC showed a documentary, ‘Tutankhamun: the truth uncovered’. DNA tests on a few of the 15 mummies associated with Akhenaten were assessed, observations made on their appearances, their lives examined – and an extraordinary theory was put forward by Dr Hutan Ashrafian, Clinical Lecturer in Surgery at Imperial College, London, whose special interest is medical history. Ashrafian pointed out that Tutankhamun’s family line died increasingly earlier and earlier; that Amenhotep III and his grandson Akhnaten/Nabihaton are known to have had visions; that Akhenaten and Tutankhamun both had feminized bodies resulting from an inherited hormone imbalance; and that Tutankhamun was born of incest, had a club foot, buck teeth, developed necrosis of the limbs and was suffering from a fractured knee at the time of his death. (His body has been digitally reconstructed and is shown in the link below.)

<See picture here>

All these elements, Ashrafian thinks, add up to a very specific hereditary disease running through the family line: Familial Temporal Epilepsy.

The idea that Akhenaten might have been epileptic has been circulating for over a century. Back in the 1900s, Arthur Weigall first proposed the theory in his book The Life and Times of Akhnaton, Pharaoh of Egypt; he saw Akhenaten as a weak child who suffered epileptic fits and hallucinations due to his misshapen skull. Weigall had read the work of the Italian 19th-century criminologist and physician Caesare Lombroso, whose 1889 book The Man of Genius argued ‘the epileptoid nature of genius’. Theorizing that artistic genius could be a form of hereditary insanity, Lombroso researched clinical descriptions and skull dimensions, citing famous artists and writers as well as religious reformers such as St Paul and St Francis of Assisi. Weigall applied Lombroso’s conclusions to Akhenaten.

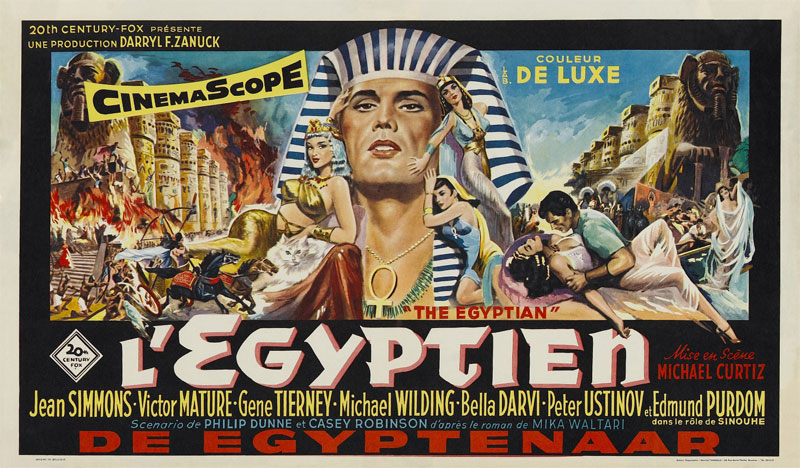

In 1945 the Finnish author Mika Waltari incorporated Arthur Weigall’s theory into his bestselling novel Sinuhe the Egyptian. Then in 1954, 20th Century Fox turned the book into a Hollywood blockbuster, The Egyptian, starring Michael Wilding as Akhenaten.

As a result of the novel and the film, most people are vaguely aware that Akhenaten suffered from a strange condition.

However, Ashrafian’s recent suggestion of epilepsy is far more scientifically based and has intrigued medical historians and neurologists worldwide – but they point out that the theory is almost impossible to prove, given there is no definitive genetic test for the condition.

Well, there may be no definitive test, but what we do have, in The Kolbrin’s Annexed Scroll 2, is the story of a king with a severe disorder that afflicted him throughout his life. Take a look at these pieces of Kolbrin text (courtesy of The Culdian Trust (http://culdiantrust.org)):

While he [Akhnaten/Nabihaton] was still a child and yet at nurse … a Formless One came up from out of its l air beside the flaming lake and entered the bedchamber … and the child was stricken. In the morning the child’s body was consumed with an inner fire lit the night before, and the breath of life struggled against the occupying demon to enter the body. In those days there lived a great physician named Mahu and he drew out the demon with things of power, and dowsed the fire with impregnated water…

…

Nabihaton rose to rule while still very young and though it is said that he died in the grip of a demon, with blood welling up from within his mouth, the other version, that he died a tombless wanderer, seems more probable, for it is so written on the Tablets of Amon…

…

The Pharaoh, the Great One of Egypt, was ill-formed in body, he was subject to uncontrolled trances unproductive of any vision. This was because at such times his spirit would withdraw, thus permitting a Dark One to enter its seat. He would fall down upon the ground and the demon spume would issue from his mouth. Therefore, at such times he had to be kept from the eyes of the people, lest they were seized with the fear of demon [sic] devastating the land and sapping its fertility. Yet not everything could be kept hidden from the people, for the Pharaoh lived as the fish within the garden pool…

When Nefare left, wickedness consumed good in Nabihaton and the chambers of his heart lay open and unprotected. Then a Dark One entered into him and drove him out into the barren places of the wilderness. It is said, “And Pharaoh fled through the wilderness, uttering horrible cries and howling as dogs howl, so that all men departed from him in fear.” Thus it came about that Nabihaton came upon Hepoa and The Master as they sat beneath the shade of a rock in the heat of the day, and the tongue of the king was blackened with the fire of the Dark One that held him. Hepoa cooled the fire within the king and expelled the Dark One, so that the king was made whole again’…

In ancient times, what we now call epilepsy was thought to be possession by a demon. Note the blackened tongue, a classic symptom of epileptic seizure. It’s also interesting that The Kolbrin refers to an earlier written source – not something you’d come across in channelled text.

There is not much doubt but that at this time he was under the control of e ither a demon or a Dark One which had taken possession of his heart…

…

The law which decreed that any one of royal blood suffering a demon-induced deformity or becoming possessed by a Dark One should be given the draught of death, was no longer enforced.

…

The events that followed remain within a shadow and none knows the truth, for it was a time of confusion. Meriten probably died of poison administered by her own hand, as was befitting. Her tomb is known, for she was not unhonoured. Some say the same potion slew the king, but others that he died of a Dark Demon within the heart. It seems that the poison was not a quick one and while Meriten died in her chamber, after pledging of the king was made he fell forward with an issue of blood from his mouth. His spirit was heard in his throat.

These are clearly descriptions of a man suffering violent epilepsy throughout his life.

Is it pure coincidence that the descriptions in The Kolbrin, published in 1994, match the very latest scientific theory about Akhenaten’s family line? To me, it suggests the Akhenaten/Nabihaton text might be authentic, and bearing this in mind, that the Kolbrin story is worth a further look to see what it can tell us about this intriguing pharaoh.

© karinlamb67 (CC BY)

Overview of Akhenaten/Nabihaton

Most of The Kolbrin is written from a metaphysical viewpoint – and, as a religious revolutionary, Akhnaten makes the perfect metaphysical subject, since his is a cautionary tale about the balance between good intention and psychological/physical weakness.

The author, though writing retrospectively, is clearly a descendant of ‘the faithful’ mentioned throughout the story. Who were ‘the faithful’? Earlier, the Book of Manuscripts tells us that ‘the faithful’ followed the ‘ways of light’ – the original spiritual teachings of Osiris brought to Egypt in its early days by ‘the Children of Light’; their teachings included ‘the great secret of how to penetrate the barrier between the two spheres of mortal and spirit’.

The Kolbrin writer gives a broad overview of Akhnaten/Nabihaton:

Perhaps it is well to give a fuller account of this Pharaoh, not as a matter of history, for this I am not competent to record, but to show what can happen when those unqualified seek to reveal the light. Also the perils that can attend such folly…

…

Nabihaton, Pharaoh of Egypt, was a strange mixture of goodness and wickedness, both carried to their extreme. I know not what his form will be in the place where the spirit stands forth in its true aspect. Certainly, we are taught that goodness cannot entirely obliterate the evil effects of wickedness. Yet how much was the king really to blame? How much can be laid at the door of his affliction, how much apportioned to the demons in his limbs? How much to the Dark Ones that possessed him?

…

The king, severed from his weaknesses, could have been a truly great ruler, a steady light before the eyes of men, the guide to a new age for the people of the land. But he was one who cast heavily on both arms of the balances.

…

This Pharaoh had many powerful opponents in high places, the tales are much exaggerated. Some, not knowing the inside of the pot, declared him to be the very light of goodness. Perhaps the truth is that in him good and evil swung out to the extremes of the balances.

© Andreuchis (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Akhenaten’s father Amenhotep III

What The Kolbrin says:

I will go back to when the father of Nabihaton, a man of great valour, much beloved by the people, became feeble through a wound that troubled him in his old age. It was then that his queen, the noble Towi, priestess of the faithful, urged him to send for the young prince Nabihaton, though he was not then so called, to become his staff and take up some of the burden. In this manner it was hoped to secure the throne of Egypt once more for one of the faithful, an end towards which the faithful had long laboured.

© Keith Schengili-Roberts (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Akhenaten’s mother TIye

What The Kolbrin says:

When his father died, the young king Nabihaton ruled in equality with his mother, they shared the royal seat and symbols.

The mother of Nabihaton was Towi, one of the Chosen Ones. In those days there were still four ranks of the faithful: the Twice Born, the Enlightened Ones, the Chosen Ones and the Dwellers in Light. Among the Dwellers in Light there were Seekers in Light and Labourers in Light. Even then as now.

…

While he had still not come to manhood, the mother of Pharaoh taught him the ways of light. She revealed many of its secrets, probably without proper authority, though this cannot be known.

…

It was the popularity of Queen Towi among the people, her wisdom and insight, that enabled the young prince to maintain his place at the king’s right hand and share the royal symbols, despite hostility by the priests of Amon.

…

When his father died, the young king Nabihaton ruled in equality with his mother, they shared the royal seat and symbols, but he acted in a manner unbefitting a son. He inclined away from the highborn ladies of royal blood, his interests were not those of a Pharaoh, and this caused the hearts of those who opposed him to rise in hope. It also isolated him from the faithful who would have been his most ardent supporters, though their loyalty remained with the queen.

Tiye, the Great Royal Wife of Amenhotep III and mother of Akhenaten and grandmother of Tutankhamun (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Tiye/Towi is known to have been an incredibly powerful figure. The Kolbrin tells us she was a priestess of the faithful, one of the Chosen Ones and a strong influence on her wilful son during her lifetime.

Change from polytheism to the worship of Aten

What The Kolbrin says:

The new form of worship introduced by this Pharaoh was simple enough. Outwardly it had all the symbols and ceremonial beloved by the people, with sufficient substance in it to attract the spiritually inclined. It could have formed a fitting gateway to the Path of the True Way … Behind the symbols and ceremonial the Pharaoh worshipped the Spirit behind the Sun, the Spirit of Light and Life as a direct fully conscious member outflowing from The Great God Behind All. The king, however, being cut off in the midst of his instruction, perceived the road but dimly. There is little doubt of his genuine desire to bring the True Light to the people, but he was not wise enough to know, firstly, that one who brings light must be one in whom light burns brightly, and secondly, that the multitude cannot be exposed to its unveiled brightness with impunity.

The king, severed from his weaknesses, could have been a truly great ruler, a steady light before the eyes of men, the guide to a new age for the people of the land. But he was one who cast heavily on both arms of the balances.

…

Undoubtedly, the Enlightened Ones and the Chosen Ones from among the faithful played some part in the introduction of the new form of worship, but unfortunately they were not equal to the opportunities of the times. This is an instance when too much concern with spirituality, too little interest and involvement in mortal affairs, can prove a fatal handicap…

To say, as many have, that the new form of worship clashed with the old established worship of Amon, is true in part only. The hopes of the faithful were nurtured in both and could have been a reconciling force, weak in power and numbers though it might have been. Superficially, and among the mass of lesser priests and followers in the two beliefs, there was antagonism and strife. While the flame of Aton waned, the sun of the new form of worship rose. But it was the popularity of Queen Towi among the people, her wisdom and insight, that enabled the young prince to maintain his place at the king’s right hand and share the royal symbols, despite hostility by the priests of Amon.

Had he dutifully followed the Path of the True Way, all would have been well. Perhaps, and this seems more likely, he did not quite understand it. Probably his intentions were good, but good intent is not sufficient… It is not sufficient for a man to proclaim a way of life for others, unless he lives according to its principles himself.

It is clear from The Kolbrin that the faithful were at odds with the more earthly-orientated whose new religious rituals threatened their traditional power and influence.

The move to Amarna

What The Kolbrin says:

Nabihaton knew enough of the Secret Mysteries to realise that he would need a new place of worship, uncontaminated by previous concentration of the twin powers, if he were to succeed in opening even the first door. Therefore, he moved his court to a new city within which was a temple outwardly dedicated to the New Light, which he enshrined before the Place of Flame. It was a sanctum for those whom he called ‘The Awakeners of the Spirit to Light’. From this we get the expression, ‘Light within the light behind the Light’, used even to this day. The priests of Amon were impoverished to pay for the new city.

Note the reference to an expression dating from Akhnaten’s time and ‘used even to this day’ – not something you’d find in channelled text.

How the priests of Amun must have hated having to pay for a new city based on a doubtful new religion! Immediately we can see how resentment started to build up against Akhenaten.

However, with the removal of the king’s household to the new city its power was diminished, the people under the two crowns became divided against themselves. The rulers became unsettled in their posts and there were revolts in the colonies towards the East. It was a time of unease because of the dispersion of the power. Now also, because of the most grievous wickedness of the Pharaoh, all the protecting divinity of his blood, which, though diminished by the generations of wilfulness yet remained potent, was dissipated. Thus, all the land suffered and was restless.

…

Within the City of the Horizon at Dawning was the Temple of the Sun’s Dawning, at which Nabihaton officiated as High Priest, but after his return with Hepoa he built a residential temple upriverwards, called ‘The Sun’s Blessing’. Some men have called it ‘The Temple of the Blessing of Light’. This was erected in three courts, one of which was called ‘Nefare’s Memory’, a place dedicated to womanly virtues.

The Kolbrin names the temples built in Amarna, and mentions a concept I haven’t come across before – a ‘residential temple’.

© isawnyu / http://www.flickr.com/photos/34561917@N04/71602094 / (CC BY 2.0)

Akhnaten – writer and aesthete

What The Kolbrin says:

He … had an unusually strong, perhaps overwhelming appreciation of beauty, as can be seen by any of his writings still in existence, though few remain of the great many there once were, and these ever in danger.

…

Perhaps the best indication of his state of mind is shown in the prayer he composed for the offering ceremony at the festival of the inturning year:

“With this sacred outpouring we sanctify You, Great God of Golden Goodness. Upon Your altar we offer pure butter, cakes of broken barley, fresh meat of clean beasts, dark bread and honey in three shades. Two kinds of beer and dark wine poured out before You.

Now we open our mouths in praise, Eternal One Overlooking Heaven and Earth. This we do, not for ourselves alone but also for the sanctified dead. Humbly we come before You, humbly we offer our meagre sacrifice and humbly we receive the gracious gifts which grant us our sustenance from day to day, and even greater gifts beyond our understanding.

We thank you for the peace filling the land with contentment.

Teach us the meaning of Your laws which we cannot understand. Look down upon us with benevolent kindness when we err. Permit us to assist in accomplishing Your will.

O Lady of Loveliness, coming forth from your place of vigil, O Lady of Protection, coming forth with your maiden attendants, speak for me with the tongue of simplicity and the heart of purity.

O Dedicated Maiden, be my mouthpiece in the inner shrine.

O Sanctified One, be the listening ear before my people. Let your goodness shine upon us as the glory above shines upon Earth.

O pacify any wrath that rises in the Glorious Heart of Heat.

I know not all the weaknesses and wickednesses of my heart, I who am mortally blind and mortally frail. I know not all the impure longings that posses me, I who am mortally blind and mortally frail. I sought for help, but it came not. I wept, but there was none to comfort me. In the night I cried for succour, but none answered. I who am great, have less than the least.

O Lady of Loveliness, intercede for me in purity and devotion”.

Never before had such a prayer been offered in sight of the people by a Pharaoh, and the people murmured that divinity had departed from the king.

Several courtiers’ tombs at Amarna contain similar prayers. Bearing in mind that The Kolbrin says the king was a prolific writer, any or all of them might have been written by him.

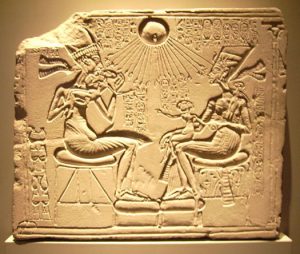

Akhenaten/Nabihaton’s ‘overwhelming appreciation of beauty’ is evident in the many statues, carvings and paintings found at Amarna; they depart radically in style from what appeared earlier or afterwards. Some incredibly beautiful art had been produced under his father, Amenhotep III; but during Akhnaten/Nabihaton’s reign two very different styles of art appeared – a formal, incised style, and later, a far more naturalistic approach. This is all well-documented and The Kolbrin has little to add.

© Hans Ollermann (CC BY 2.0)

© Keith Schengili-Roberts (CC BY-SA 2.5)

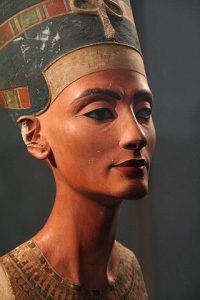

NEFERTITI

On the strength of a single small statue, the wife of Akhnaten is thought to be one of the world’s most beautiful and elegant women. She had several daughters by him and then seems to have disappeared from public life. During the later part of Akhnaten’s reign a co-regent appeared on monuments called Nefernefruaten wearing all the attributes of kingship, which has led Egyptologists to think that Nefertiti took over the throne in the years after Akhenaten’s death. Nefertiti’s body has never been identified.

© bittidjz (CC BY-SA 2.0)

This is what The Kolbrin has to say:

When their Pharaoh showed no inclination to marry, and strange rumours were heard about him in the streets and marketplaces, the people became disturbed and uneasy. Also, the highborn ones about him, the court officials, the princes and governors of the land, were perturbed at his interest in the Mistress of Songstresses at the Temple of Amon in Victory. The faithful were perturbed also, for within this temple was one of their secret shrines. This could have been the turning point for the faithful in Egypt, had the king been other than he was, for there were several princesses of the royal blood numbered among them. As it was the faithful were antagonised.

Then it was that some of the faithful from the city of the old royal residence, not from the new one as told, contacted the eyes and the ears of the king, so that the Pharaoh was counselled to take himself a wife. In this manner alone could the clamour of the people be stilled and their hearts put at ease. It was then that the High Priest at the Temple of the Visible Light, by a cunning move brought the young princess called Nefare, in our tongue, before Pharaoh. She was a temple maiden, daughter of a king, and one devoted to The Great God in Silence.

Pharaoh took her to wife, but he showed her little affection, though she was not unbeautiful, even if with a beauty not of this land. Nevertheless, in the eyes of the people the marriage appeared successful enough, though perhaps the outward display of affection was overdone. Still the queen, being more frail than Egyptian women, could bear only daughters .. . Things were not as they appeared and Nefare despised the king in her heart for his secret wickedness.

The Kolbrin tells us that Nefertiti was not Egyptian, which scholars have long suspected. That the pair shared little affection is, however, a revelation, suggesting that all those stone carvings showing the family firm of Akhnaten & Family were just state propaganda.

Wikipedia (CC0)

It was the wife of Pharaoh who influenced him to disclose some of the mysteries which … had been … very carefully hidden. Thus, though the forces of evil had prevailed in the land they had not uncovered the Inner Shrine of the Sacred Mysteries. Such mysteries as they had discovered proved of little value to them and were soon so distorted and perverted as to be useless. The great secret of how to penetrate the barrier between the two spheres of mortal and spirit was still completely secured. If nothing else its very dangers would have safeguarded it.

Actually, though it is said that Secret Mysteries were disclosed, this did not happen. All that did happen was that Pharaoh used the knowledge he had to try and give the people a greater insight into the way of light, the True Way. As is ever done he veiled the all -consuming brilliance of Truth, leaving just sufficient glimmer to light the way, to become a beacon. Nabihaton himself saw the Truth but dimly, for though he tried he failed to meet the tests of an Enlightened One. Perhaps it was this that inclined him away from the faithful. How many, when they discover what the knowledge of Truth entails, falter on the path?

Spelt out here is one of Akhnaten/Nabihaton’s chief weaknesses: he had failed to become an Enlightened One; he was ‘unqualified … to reveal the light’. The Kolbrin says that the Enlightened Ones were a spiritual elite to whom certain mysteries were revealed, though it seems they did not have to go through the incredibly dangerous ordeals undertaken by others who aspired to become Twice Born. That the pharaoh himself, the country’s spiritual leader, should have failed to become an Enlightened One (presumably on grounds of spiritual inadequacy) would have been humiliating for Akhnaten/Nabihaton, and would almost certainly have turned him away from the religion of Amun.

Now, as the years went down into dust, the land of Egypt crumbled and began to fall apart. Nefare, because she followed the pure light, could not dwell with Pharaoh while the life he led was an abomination against purity. She was an ever faithful one, though in her disgust she must have been tempted to be otherwise. The queen removed herself and her household in the fifteenth year of the reign of Nabihaton.

Interesting that one of the Amarna temples mentioned earlier was called ‘Nefare’s Memory’. Was this another way of saying ‘In Memory of Nefare’, suggesting that Nefertiti had removed herself from public life by the time the temple was built?

It was then put about, by those who licked the feet of Pharaoh, that she was a fickle woman of wanton ways. They said she was an adulteress and called upon her beauty to bear witness against her. What they said was false … Surely there can be no doubt that the Pharaoh was abnormal, for how could any but an abnormal one treat such a woman thus? Nefare sought refuge in Lebados where there was a secret shrine to The Great God, and resigned herself to a life of great virtue.

…

When Nefare left, wickedness consumed good in Nabihaton and the chambers of his heart lay open and unprotected.

Nefare is described here as one of ‘the faithful’. ‘Lebados’ could well be a skewed version of Abydos, where one of the greatest and most ancient temples in Egypt was dedicated to Osiris, whose ways the faithful followed.

Neferuten/Nefernefruaten

Towards the end of the Kolbrin story, an odd piece of text reads:

Of Neferuten, wife of Upofa, men say she established the Sisterhood of Sin, but this is untrue, for they misunderstand the writings. The written things are misread… Neferuten was, of all women, the most virtuous; yet surely no woman ever evoked such malice in the hearts of her sisters!

‘Neferuten’ could be a skewed version of Nefernefruaten, who according to archaeological evidence reigned as pharaoh toward the end of the Amarna Period. This text seems to refer to the Nefare/Nefertiti described earlier – the virtuous wife who evoked such envy and malice in women around her. (I’ve had no success trying to decode ‘Upofa’.)

Akhenaten/Nabihaton and the Mistress of Songstresses

I have … mentioned another son [of Akhenaten/Nabihaton], one born to the Lady of Songstresses, and he was bound to a different destiny altogether.

The son born to Pharaoh by the Lady of Songstresses was also born to high estate through her. I will not record his name, lest even now it be used with evil intent, for it is a name of power. I will not disclose his titles but call him just what he was, ‘The Master’.

The king had a son by the Lady of Songstresses, one destined for greatness, though his greatness was not perceived by the eyes of men. When, later, this son was exiled to wander in strange places, his mother cast herself into the arms of Sebuk, but this is something the telling of which has no place here.

Sobek/Sebuk was the crocodile god associated with the River Nile – which seems appropriate, bearing in mind the Lady of Songstresses’ son was carried away by a vessel.

When The Master was born, Pharaoh was quite indifferent towards him, though, through the nature of his blood, he was not unexposed to danger. The account of how the child was stolen from the temple garden by the priests of Amon; how it was rescued by a Syrian in the services of Nefare, disguised as a woman vendor of spices, and Seltis, a Captain of Craft, is known and need not be retold. However, though it is true that the child was carried away by a vessel, he was not taken to the lands of the Henbew. He was not brought up in the household of the Captain of Craft. The child was left at the Temple of Anthor in Splendour, where sweet waters kiss the bitter, and brought back to the City of the Horizon at Dawning. Later, both child and mother were taken into the royal household, for the two women had long been friends, even before Nefare became queen. Yet Pharaoh knew not that the manchild within the household of Nefare was his, for the tale had been put about that the son of the Lady of Songstresses was dead. Thus, even in the shadow of the royal household The Master grew up to walk in the path of Truth.

Without the temple gates at Lebados, beneath a sycamore tree, dwelt a three-eyed man called Hepoa, one who could foreknow the future, who had the gift of farseeing, but he was aged and infirm. One day The Master chanced to pass that way and he came upon Hepoa as some youths mocked him and cast sand upon his head. Then the heart of The Master was filled with wrath and, taking up the staff of Hepoa which lay upon the ground he laid it on the backs of the youths and they were discomfited. When they had fled he succoured the old man and, returning into the city, brought forth food so that Hepoa ate and was made content. Then The Master sat at the feet of Hepoa and heard his words, for they were words of wisdom and Truth. Hepoa was one who knew the mystery of The Great God and the secrets of the hidden places, for he was one of the Twice Born. Thus, The Master became the old man’s staff. Eventually, the day came when the two journeyed to a secret place within the wilderness, so that The Master might approach the threshold.

I have included this and an earlier passage mentioning Hepoa because he features large later in Akhenaten/Nabihaton’s story.

It has been tentatively suggested that this illegitimate son of Akhnaten who grew up to become The Master (a title given to great spiritual figures throughout The Kolbrin) could have been Moses – but since The Kolbrin only mentions a shadowy parallel in the child’s early life and the fact that he grew up to be great, it is only of passing interest.

Archaeologists have drawn attention to another royal wife of Akhenaten called Kiya, possibly a Mitanni princess. She was an important figure at Akhenaten’s court in Amarna during the middle years of his reign when she bore him a daughter. In inscriptions, Kiya is called “The Favourite” and “The Greatly Beloved.” She is not mentioned in The Kolbrin. Could she perhaps have been the Mistress/Lady of Songstresses? The Lady of Songstresses was born to high estate; and, looking at images of Kiya, I notice that she often seems to wear the oversized earrings favoured by singers and dancers – but these are tenuous suggestions.

© louise_al (CC BY)

Meritaten

By now, readers might be puzzling over all those scurrilous scraps scattered through The Kolbrin text. What on earth could Akhenaten/Nabihaton have been up to that was so wicked? Early on in the story it says that he inclined away from highborn ladies; I take this to mean that as an adolescent he liked low life. ‘In the streets and marketplaces’ could mean anything from female prostitutes to rent boys to rough trade.

But it was what happened later in his reign that so appalled Nefertiti/Nefare and all his people. Here is the Kolbrin version of what happened:

Within the City of the Horizon at Dawning … he [Akhenaten/Nabihaton] built a residential temple … erected in three courts, one of which was called ‘Nefare’s Memory’, a place dedicated to womanly virtues. There, when she came of age, his daughter by Nefare, a maiden called Meriten [Meritaten], was consecrated in service.

There is a description of this maiden in a scroll kept at the shrine dedicated to the Martyred Maidens of Chastity, at Nomin, the city of forgotten wickednesses. It says, “As I stood before the gate called ‘Treasurer of Life’, on one pillar of which was engraved the words ‘When the eyes see, the ears hear, and the nose smells, they transmit to the spirit, that it understands’, I saw the young daughter of the king. She was not tall or fat and her feet were delicately formed. Her curls were long but tied back from her face and anointed with sweetly fragrant oils. She passed close by and I noticed her garments gave out a delicate perfume. Her eyes were large and unusually long-lashed. Her glance was soft and restrained, her whole bearing modest. Her skin was lighter than the pale copper of Askent, like the cherished ostrich egg, soft as the finest oil. Her nose was perhaps slightly larger than usual but fine and delicately formed. Her mouth was small, though the lips were full and even then tantalising with secret promise. About her head was a circlet of gold and she wore a necklace of gold and blue stones. She was clad in a pure garment of fine linen fringed above and below with blue and red. Upon it were workings of gold ornamentation. On her arms were bracelets of burnished copper interwoven with gold and silver. She had just come from the sacred grove and the glistening dew of morning still dampened the lower fringe of her robe. In one hand she carried two small bells of copper and in the other a small hammer of gold.”

© Hans Ollermann (CC BY)

It was after the consecration of Meriten that the eyes of Nabihaton wandered towards her lustfully, but perhaps, to do him justice, he should not be judged by the same standards as other men. He was the Pharaoh of Egypt, who, according to ageless tradition, was above wrongdoing. There is not much doubt but that at this time he was under the control of either a demon or a Dark One which had taken possession of his heart. Also, he had been brought up to a code where inter-family love and marriage were accepted as the rule, where the sanctity of the royal blood and the need for its conservation in purity was believed in as a law. Then, too, despite his unnatural longings, which he lacked the strength to control and subdue, there is no doubt that he could and did experience extremely deep feelings of affection.. .

Anyway, he did take his daughter in awful wickedness, his evil thoughts displaying themselves uncontrollably. Now he took no care to hide them. Throughout the new city he caused the name of Nefare to be struck out and the name of Meriten was put in its place.

<See picture here>

Although it had been accepted that the kindred of the Pharaoh could inter-marry, any union between parent and child was absolutely forbidden. This law from days long past was still binding.

In the exhibition catalogue Pharaohs of the Sun: Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamen (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1999) the Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves writes: ‘The princess was promoted to the position of Great Royal Wife, presumably to fill the ritualistic void… the new queen was still little more than a child. Notwithstanding the daughter’s tender age and the essentially functional character of the title “Great Royal Wife”, scholars have long suspected the relationship between Akhenaten and Meretaten ultimately to have been a sexual one … Since, unlike other forms of incest, no divine precedent could convincingly be cited, it was an arrangement that must have appeared abhorrent even to contemporaries.’

The Kolbrin states unequivocally that it was abhorrent to the Egyptian people.

Now, when Pharaoh took Meriten in grievous wickedness, the people murmured, but none arose among them to do more, for such is not the custom of the land. Towi, the great and good who had lapsed into but one form of wickedness, was no longer there to restrain him. Nor in all probability could she have done anything, for he was Pharaoh. But when it came to the ears of Hepoa, he took himself into the wilderness and fasted there for seven days. He then returned and gained audience with Nabihaton.

Hepoa went before Pharaoh and there, in the midst of his court, he denounced him. These were the words issuing from the mouth of Hepoa, as set down by the attending scribe: “O great and mighty Pharaoh, where once the stormwind raged there is now a gentle breeze. Where once the diligent shepherd stood, now a musician sits and idly plays. The land is no more as it was and no man remains content within his dwelling. The northwind has ceased to enter the land and the southwind eats it up. A heavy hand lies on the hearts of men and their limbs are sluggish, they are languid and move no longer as once they did.

Wherefore has all this come about, the people ask, and I answer them truly, it is because the protective power has departed from the blood of the Pharaoh, it is because of the iniquity in the palace. This is a time of woe. These things I have spoken before the eyes and ears of Pharaoh, beyond the palace gates. Yet it is not in me to leave them unsaid before the face of the king himself. Where is the great one who sets goodness in the place of wickedness? Where is he who replaces injustice with justice, who hears the cry of the lowly? Who causes right to prevail in the land? Where is He? I look and I look in vain.

I see only one who has defiled the protective treasures, the glory of Egypt, with iniquity. I see only one who has polluted the pure stream with the sewage of evil, who has succumbed to the ultimate in wickedness. This I see, as all men see it, but I am one who sees more. I see an Egypt gone down into dust. I see plague and death stalking the streets. I see the fertile black waters turned back on themselves. I see the black land buried beneath the sand. I see grim-faced men coming from out of the East to stamp the land flat in blood. I see the dread things of the past recurring. I see desolation spread out on every side.

Woe to you, great Pharaoh, woe to the land of Egypt! Goodness lies dying beneath the triumphant foot of evil. Virtue is betrayed into the foul hands of loathsome lust, her despairing cry unanswered by any coming to her aid. Wickedness walks unhampered through the cities and wrongdoing is seen on every side. Woeful are these days and doomed are those who endure them. What does the great light shining forth from the palace conceal, sacred mysteries or secret sins?”

Then the arm of Pharaoh stretched forth to stop the mouth of Hepoa, and it was stopped. He was led forth and whips were laid on his back, and he was placed within a dungeon.

…

The events that followed remain within a shadow and none knows the truth, for it was a time of confusion. Meriten probably died of poison administered by her own hand, as was befitting. Her tomb is known, for she was not unhonoured. Some say the same potion slew the king, but others that he died of a Dark Demon within the heart. It seems that the poison was not a quick one and while Meriten died in her chamber, after pledging of the king was made he fell forward with an issue of blood from his mouth. His spirit was heard in his throat. Thus, it does not appear that they were slain with the one cup. It is unlikely that Meriten died by any hand other than her own, though this is said.

What a story.

But is that all it is – just a story? The 2015 BBC documentary, ‘Tutankhamun: the truth uncovered’ aired a second new theory in addition to the epilepsy claim. One of the 15 DNA-tested mummies, known only as ‘the Younger Woman’, was said to be not only the mother of Tutankhamun – but also, it is thought, Akhenaten’s sister.

The Kolbrin tells it differently. It states that one of two sons ‘born under the darkest cloud’ and ‘conceived in wickedness’ ‘became king of Egypt in his day’. ‘The darkest cloud’ and ‘conceived in wickedness’ can only refer to the incestuous union between Akhenaten/Nabihaton and Meritaten/Meriten. In other words, Meritaten/Meriten was the mother of the son who became king of Egypt in his day – Tutankhamun.

And findings are getting steadily closer to the Kolbrin version of events. In December 2015 the French archaeologist Alain Zivie and Egyptian officials unveiled the tomb of Maia, Tutankhamun’s wet nurse, at Saqqara. Zivie has been studying the tomb carvings and is now convinced that the woman known as ‘Maia’ is none other than Meritaten. Watch this space…

Tutankhamun

This is what we know about Tutankhamun from inscriptions and archaeology:

Pharaoh Tutankhamun (1333-23 B.C.): the short-lived boy-king whose relatively unlooted tomb was discovered by the English archaeologist Howard Carter in the early 1920s (“Can you see anything?” “Yes, wonderful things.”). The whole world was mesmerised by his funeral wealth, now in the Cairo Museum. During Tutankhamun’s short reign, power was held by Aye, who ruled for four years after Tutankhamun’s death, and by the general Horemheb who followed Aye. Under Tutankhamun the old religion with its many gods and temples was restored. Recent DNA tests have confirmed that Akhenaten was Tutankhamun’s father, but a big question mark hovers over the identity of his mother.

And here is what The Kolbrin has to say about the short-lived son of Akhenaten/Nabihaton:

I have mentioned the surviving son of the king, one born under the darkest cloud, the secret of whose ill-omened birth had been unrevealed, though it was known to a few. Some of these were antagonistic to the new form of worship proclaimed by the king and they used this knowledge to their own advantage.

…

The son of Nabihaton, one conceived in wickedness, was slain in battle [Smenkhkare?], therefore the younger son, one also born of the union of evil, became king in Egypt in his day.

…

While yet young he became a follower of the new rites of mystery which his father had set up in imitation of the Mysteries of the Hidden God. These new rites were themselves hidden within a new form of worship set up by Nabihaton. Of themselves these were not things of wickedness, but they inclined too far towards ritual which was futile and ceremonial that was purposeless. Though the new mysteries served to spiritualise and could awaken the spirit, they went just so far and could go no further. They led to a dead end. They went as far as the Grim Threshold, but could not lead beyond it.

As far as the faithful were concerned, the setting up of a new form of worship made little difference to their position in the land, but they did attempt to draw the young prince wholly within their fold. Because of his manner of life, the king, his father, was precluded from this.

…

The next Pharaoh [after Akhenaten/Nabihaton] married his sister, conceived in wickedness, and therefore died while yet young.

…

The predictions of Hepoa were averted by the happenings in the land, happenings that purified it during the days of Pharaoh’s short-lived successor.

The Kolbrin tells us that Akhenaten/Nabihaton’s son started life following his father’s new religion, but was gradually drawn back into the ranks of the faithful and the old religion.

Akhenaten/Nabihaton’s death and its aftermath

What The Kolbrin says:

Some say the king died after being carried to his chamber, others that he recovered, but the truth is unknown, for at this time the signal was given and the people arose in the streets. The new worship, which nevertheless was an outgrowth from the bulb of Truth, died away as the growth dies back on an onion. But like an onion, the bulb remained. The new worship was not unwelcome in the land of Egypt and would have survived had not its founder led an impure life. The hostility by priests of the other forms of worship would not alone have sufficed to extinguish its light. It was the maggot in the heart of the flower he raised that caused it to fall apart. To establish a pure form of worship and beliefs its founder must also be pure of hands and heart.

Whatever happened Nabihaton was never placed within the tomb he had prepared for himself. Some say because Hepoa cursed it, but this I doubt … Some say Pharaoh was buried with his wife, but who knows the name of the woman in whose tomb he is said to lie? I think, however, it is more likely that he is a tombless wanderer, which is not so strange when the record is considered fully. … The next Pharaoh married his sister, conceived in wickedness, and therefore died while yet young.

The predictions of Hepoa were averted by the happenings in the land, happenings that purified it during the days of Pharaoh’s short-lived successor. Then came a great one to rule the land, and peace and prosperity returned. Of his times this is written: “Be joyful, O people, for a time of gladness had descended upon the whole land. A righteous and royal king has been set over us, one truly favoured in the eyes of the Great Ones. The waters rise and fall in moderation, the days are long and productive. The hours of night are measured and restful. The moon maintains her appointed seasons and the sunship steers a straight course. The bright torch of Heaven burns steadily and the stars retain their stations. Once more, men must qualify by goodness for the right to govern and to hold official positions. All is well with the land”. If this could be but written of these days!

It’s difficult to know precisely who this ‘great one’ was, who came to rule the land. Aye, who succeeded Tutankhamun, and after him Horemheb, could be said to have purified Egypt by destroying Amarna and all evidence of Akhenaten’s reign – but each of them ruled for just four years. Sethos I, who came afterwards and ruled for 11-15 years, re-established order and reconquered most of the disputed territories for Egypt. That’s as much as I know.

Incidentally, the lines referring to the untroubled state of the waters and the planets are not just hyperbole. Earlier in the Book of Manuscripts a scribe writes:

My land is old, a hundred and twenty generations have passed through it since Osireh brought light to men. Four times the stars have moved to new positions and twice the sun has changed the direction of his journey. Twice the Destroyer has struck Earth and three times the Heavens have opened and shut. Twice the land has been swept clean by water.

Records of these earlier, terrible happenings had clearly been handed down for generations, and the Egyptian people considered themselves blessed when all was well with the land and the heavens.

The moral of this cautionary tale

The Kolbrin’s story of Akhenaten ends on a note that rings down the centuries:

Once, men said that the king was the shepherd of everyman and that wickedness was not in him. That however lowly the man in distress, he would devote hours of his time to bring him justice.

If our fathers had but known the nature of the men who would follow as kings, or had the kings of olden days foreseen what was to come, the sons of the kings would have been destroyed even though they were the seeds of divinity.

Perhaps we do injustice to our rulers, for when the governors are bad maybe they are no worse than a corrupt, degenerate and indifferent generation deserves.

When you decry your rulers, read the hearts of your people.

© AtonX (CC BY-SA 3.0)

[N.B. Images have been chosen purely for their visual content and not for the opinions on the websites from which they have been taken.]

A great and fascinating read. Thank you.

I would like to add a grain of salt to the mix. We all know by now that mainstream media is capable of very effective demonization, used to suit the requirements of hidden powers. What if there was an element or even a great deal of that propaganda and disinformation in the texts of the time of Akhenaten, and continuing later, in order to utterly destroy for all time his reputation as a Sun/Mother worshipping, family-friendly, sympathetic character?

A perfect example of such tricks can be seen here. Who said what and why? “It was then put about, by those who licked the feet of Pharaoh, that she was a fickle woman of wanton ways. They said she was an adulteress and called upon her beauty to bear witness against her. What they said was false … Surely there can be no doubt that the Pharaoh was abnormal, for how could any but an abnormal one treat such a woman thus?”

How can we be sure of any of this, or of much of what we read today, if we have no other voice with all the necessary requisites of truthfulness and presence on the ground? Don’t misunderstand me. This is not a criticism of arguments put forward in this article which is extremely informative and clearly well-grounded. The point I’m making is not related to that.

The fundamental fight was one of patriarchy versus matriarchy. The worship of the Great Matriarch had been thoroughly stamped out by the time of Akhenaton, and there was no way She would be allowed back! Imagine the cost to the priests who controlled all worship. It could be that a lot of damage was done with words as well as deeds. Clearly, the opposition was not stupid.

Since my interest lies in the archaic cuneiform symbols and their meanings, I suggest this:

AMAR means ‘To care for’ in archaic Sumerian, with the emphasis on children. Behind this, we find AMA, the mother and love. (see the electronic Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary ePSD for confirmation of these definitions). To call his created city ‘Amarna’ was to indicate that this was a place where a parent (or two) would love and nurture their children, and by extension, we might understand that Akhenaten intended to also be a father figure to its inhabitants.

Then, we read “Of Neferuten, wife of Upofa, men say she established the Sisterhood of Sin, but this is untrue, for they misunderstand the writings. The written things are misread…”

SIN in Sumerian means ‘three’, and it refers to the three phases of the moon with the metaphor of three women, the three stages of life; youth, maturity and old age. This reference is well attested in mythologies. The word ‘SIN’ has been passed down all that way to us but with the deliberately perverted meaning that we know today. The ‘Sisterhood of Sin’ was what we might call today ‘The Sisterhood of the Three Fates’ or ‘The triple deity’.

“Neferuten was, of all women, the most virtuous; yet surely no woman ever evoked such malice in the hearts of her sisters!”

MAL in Sumerian is the offering basket – offered to the Great Matriarch in the sky. Her sign is AMA. This is shown as a basket with the sky inside it, MAL x AN (basket containing the sky). AMA x AN (mother and sky) and can be seen here: Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative, CDLI, Reference P001344

I would suggest that MAL was also deliberately perverted from its original and infinitely more ancient meaning. Today, MAL gives us the French word ‘mal’ which means ‘bad’. It also give us ‘malice’ derived from French as so many of our words are. But then again, the French MALLE means a suitcase or trunk, so perhaps the Mother and her offering basket are still to be found somewhere in our collective memory…

You might be interested in reading the story of womankind as told in The Kolbrin. It would probably provoke disbelief and angry reaction from feminists and rationalists alike. Have a look at the Book of Creation chapters 5-6 and Gleanings chapters 1-2.

M Daines: What an insightful comment to an excellent and “meaty” article! I really enjoyed both the main work and your thought-provoking ideas. My kudos to Yvonne Whiteman for putting it all together so well, and you for adding another dimension: “the fundamental fight,” which continues to this day…

In your comments I hear the voice of our time: when everyone has their own agenda, who and what can we believe? Where can we find a source with all the necessary requisites of truthfulness and presence on the ground? Well, call me oldfashioned, but I don’t think The Kolbrin is just another voice. This is why I wrote the article. The Book of Manuscripts is not primarily historical; it doesn’t set out to make or destroy reputations and, try as I may, I hear only the voice of reason in what the writer has to say. He wonders how much of Akhenaten’s behaviour could be attributed to his illness and how much to personality defects. He admits that had he not been afflicted by a demon, Akhenaten might have been a truly great ruler. He is puzzled by the negative information spread about the king. He shows great sympathy for Nefertiti, but he sees the king’s more positive side too. For him, Akhenaten was ‘a strange mixture of goodness and wickedness, both carried to their extreme’, ‘one who cast heavily on both arms of the balances’. He actually admits that he cannot form a satisfactory opinion about Akhenaten’s character. This doesn’t sound to me like disinformation.

I wonder what the writer would have thought of our own time. Nowadays incest, rather than being hidden away, is gradually being dug out of its can of worms and held up for all to judge; human beings often breed in the full knowledge that they may be passing on debilitating genetic traits; and disability is redefined as ‘differently abled’. We are told in this story that centuries earlier, Akhenaten would have been given ‘the draught of death’ in early childhood so that he would not weaken the royal bloodline any further. What I find interesting is that the writer sets out the facts but does not take sides.

How long can a campaign of disinformation go on? The ‘great ruler’ who came later might even have been Ramses II, who tried hard to obliterate the Amarna period from Egypt’s memory. Clearly, the author is writing at least several reigns on; after describing how the land eventually became stable again, he adds despairingly, ‘If this could be but written of these days!’ – which suggests yet another falling off in Egypt’s fortunes.

Archaic cuneiform symbols… Do you know anything about the ancient history of the Coelbren alphabet? If so, it would be great to hear from you at [email protected].

Yvonne, I see what you’re saying about The Kolbrin. I knew nothing at all about this before reading your latest article here. It seems that he or she was a maverick of their time, refusing to take information at face value. My comment was rather that whoever wrote The Kolbrin might well have been faced with a really massive disinformation campaign, something difficult to deny, and to offer a reason for that. So we don’t disagree. As to how long a lie could go on, I suppose it would depend on the force with which it was propagated at the outset and that again would depend on the reasons for it. Maintaining religious and political power meant exterminating paganism and the Great Mother figure. You can’t fight nature. But eliminate the Matriarch, and turn woman from equal into whore…I think the ripples from that old stone are still moving to some degree! And the reasoning behind it is still there – quashing natural spirituality in order to keep control.

In answer to your question: No, I don’t know about the Coelbren alphabet. Sounds interesting… Thanks for your comment,Bethany.

If you havent checked out Immanuel. Velikovskys books you defintely should. He did some outstanding and unique research on the timeline post exodus, and tied up all sorts of loose threads that somehow still persits to present day. Largely in part because of a hostile academia that did all sorts of outrageous actions in order to have Velikovskys scholarly voice silenced.

Outstanding!