Note from the Author: Alongside its Egyptian Books, the enigmatic Kolbrin contains five Celtic books whose provenance is unknown. Most people dismiss the books as forgeries. I am convinced that their core material is genuine.

Glastonbury: the greatest music festival of them all with its Pyramid Stage, army of tents, skunk truffles and muddy ecstasies around Pilton’s Worthy Farm. Every year things get bigger, and just down the road Glastonbury’s high street shop names proclaim the alternative message loud and clear: ‘The Goddess and the Green Man’… ‘The Speaking Tree’… ‘Starchild’…

But Glastonbury resonates with far more than music and crystals. Even the most hardened festival-goer senses there is something different about this place nestled in the heart of the Somerset Levels. Mediaeval pilgrims called it the ‘holyest erth of England’, while 21st-century YouTubers consider it ‘the spiritual capital’ and ‘most pagan town in England’.

Distant view of Glastonbury Tor, photo Michael W Beales BEM (CCBYSA 2.0)

Why has this small hill in the misty Somerset marshes exerted such a pull over the centuries? Why have its Tor and sacred places beguiled ranks of Christian pilgrims, goddess-worshippers, earth-energy dowsers, wizards and witches, festival-goers, New Agers and travellers alike? Why has a tangle of myths entwined with history and thickened into an enchanted forest? Jesus was said to have come here as a boy with his great-uncle Joseph of Arimathea, inspiring William Blake to write Britain’s alternative national anthem, Jerusalem. When Joseph of Arimathea fixed his staff in the ground on Wearyall Hill, it took root and its offshoots have blossomed ever since, despite attempts by vandals to chop it down. The island of Avalon, on which the town stands, is where the dying King Arthur was carried in a barge by three queens and the Lady of the Lake after his final battle. It is the place where the body count salvaged from the 1184 fire that destroyed Glastonbury’s tiny wattle church included the illustrious saints Patrick, Dunstan, Oswald, Indractus and the historian Gildas. The number of saintly burials grew and grew until by the 14th century, 300 saints were taking their final rest at the rebuilt Abbey—which had become so vast and spectacular that in Italy it was known as ‘Roma Secunda’, the Second Rome. It is where, in 1191, monks claimed to have found King Arthur’s and Queen Guinevere’s grave. For many hundreds of years, Glastonbury was one of three places in Britain considered so sacred that, for some time, the service of God was carried on there unceasingly day and night by perpetual choirs. The other two were at Llan Iltud Vawr, now Llantwit Major in South Wales, and Ambresbury in Epping Forest, where Queen Boudicca made her last stand against the Romans. Ambresbury is known to have been destroyed around 554 AD, so Glastonbury’s Church foundation can be dated to an even earlier period.1

Glastonbury Abbey ruins, photo Steve Slater (CCBY2.0)

Glastonbury Abbey, Lady Chapel ruins, photo Chris Talbot (CCBYSA2.0)

When King Henry VIII dissolved Glastonbury Abbey and had its Abbot brutally murdered in 1539, the town and its island gradually faded over several hundred years. But with the 20th century came a remarkable revival. The architect Frederick Bligh Bond used psychic archeology and automatic writing to excavate Glastonbury’s ancient Abbey ruins. The Baháʼí spiritualist Wellesley Tudor Pole secured the Chalice Well Garden for peace and healing in perpetuity. The writer and artist Katharine Maltwood saw a vision of the ‘Temple of the Stars’, now known as the Glastonbury Zodiac ‒ a colossal map of celestial zodiac signs set in 30 square miles of Glastonbury landscape taking in roads, streams and field boundaries, which, she believed, dated back to Sumerian times. Occult books by the ceremonial magician Dion Fortune revitalised pagan Wicca. The historian Geoffrey Ashe resurrected the charismatic legends of King Arthur. Last, but not least, a generous-spirited Quaker farmer and devotee of William Blake named Michael Eavis started an annual rock music festival, which transformed the sleepy little town into a household name worldwide.

The Summerlands

In ancient times, the Somerset Levels, one of the lowest, flattest areas of Britain, were known as ‘the summerlands’ because they were too wet to use in winter. Their rich summer grazing land may have given rise to the name ‘Sumersata’ ‒ ‘land of the Summer people’ ‒ from which Somerset takes its name. Before the Levels were drained, the settlement of Glastonbury stood on the Isle of Avalon near a bigger island called Wedmore in a tidal sea amid dense reeds, freshwater marshes and wetlands linked only to the mainland by an earthwork called Ponter’s Ball2, so usually reached by boat.

The Somerset Levels landscape in 700 BC, South West Heritage Trust (adapted by AMLP) https://avalonmarshes.org/, reproduced with permission.

The early farmers using the islands for their summer hunting built wooden trackways across the reed-swamps, among them the Sweet Track, one of the oldest timber trackways discovered in the British Isles.

Reconstruction of part of an oak trackway near Glastonbury on the Somerset Levels, dendrochronologically dated to 3807-3806 BC. Photo Richard Webb (CCBYSA2.0)

The Island of Glass

The name Glastonbury or Glestingaburg (Old English) literally means ‘Glass-town-borough’, and its earlier Brythonic name Ynys Witrin is thought to mean ‘Island of Glass’. Scholars dispute this – for what on earth has Glastonbury to do with glass?

A great deal, as it happens. The Kolbrin’s Britain Book, a history written in the early centuries AD and one of the five Celtic Books of the Coelbook3, states matter-of-factly:

‘Here was the resting place for the souls of the dead, where they received their last sustenance before passing through the glass wall. From here ran the old road to the place of light where the brightwinged spirits flew freely in the place called Dainsart in the old tongue.’4

In other words, the Island of Avalon, known as ‘the Isle of Departure’ in the Britain Book5, was a place where the souls of the dead—not bodies, but souls—received their last sustenance (music and prayers, perhaps?) before passing through ‘the glass wall’. This was clearly not a solid glass wall but a mystical barrier—a misty, semi-transparent curtain or veil between the world we mortals know and another dimension. Science refutes the existence of other dimensions, but the Kolbrin refers to the ‘Otherworld’ behind ‘the impenetrable veil’6.

The Kolbrin’s Egyptian Book of Creation tells how, many thousands of years earlier in the Indus Valley’s Gardenplace, a Son of God called Dadam (Adam) ‘became a servant of the Sacred Enclosure where the misty veil between the realms could be penetrated, for all those having the blood of Aruah [Dadam’s female ancestor] had twinsight, an ability to see wraiths and sithfolk, ansis and spiritbeings, all the things of the Otherworld, not clearly but as through a veil.’7. Dadam and the other Children of God did not evolve naturally: they had been artificially engineered by the ‘Grand Company’ or Annunaki8. But when these part-earthling, part-extraterrestrial Children of God mismated9 with two different species of primitive hominoid living around them, they changed human DNA for ever and their descendants—we humans—not only experienced shorter lives and all kinds of diseases thereafter, but lost the use of our ‘third eye’ which the Kolbrin calls the ‘Great Eye’10 ‒ our psychic ability to see into the Otherworld. Our perception of the Otherworld decreased until it became almost opaque and closed to human view, although a remnant of psychic ability still exists in some of us.

Places where the misty glass wall of the Otherworld could be penetrated, such as the Gardenplace in the Indus Valley (transformed into desert by climate change many thousands of years ago) and the Isle of Avalon, were few and far between. The Kolbrin only mentions these two sites as having breaks in the veil, though there might have been others. This, says the Britain Book, was what made Glastonbury so remarkable and, judging by its spiritual zeitgeist, still does.

Why is the wall called ‘glass’? It is unlikely that a solid glass wall ever existed, but glassware was known before the coming of the Romans through Phoenician trade and was seen to have a misty, see-through appearance. The earliest glass technology, Alexandrian glass, originated in Egypt11 and was described by Pliny the Elder as ‘colourless or transparent, as closely as possible resembling rock crystal’12. What better metaphor could there be for a window into the Otherworld?

Ancient Roman glassware, 2nd century BC, thought to have been imported from Alexandria, Egypt, Archaeological Museum of Perugia. Photo G.dallorto (CCBY)

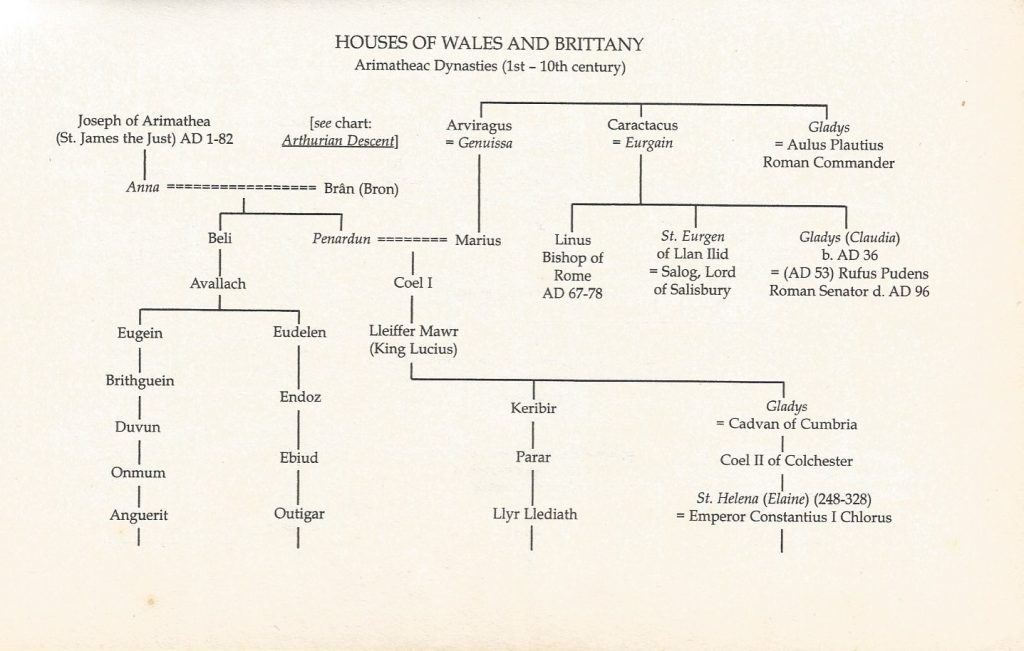

The Celtic Book of Origins tells of ‘the days before the misty veil became impenetrable and Evalak ruled the isle containing a forest of fire-apple trees, which men now misunderstand’13. It also says that Evalak was ‘Guardian of the Gate’14. The Welsh spelling of Evalek is Avallach, also spelt Avalek – Evalak-Avallach-Avalek. The Britain Book tells us that ‘Joseph Idewin [Joseph of Arimathea – more on him later] was related to Avalek, whose kingdom bordered that of Arviragus, through Anna the Unfaithful’15. Put together, this indicates that in distant times on Avalek’s island—the Isle of Avalon—people with strong psychic ability could see or slip through the misty veil/glass wall into the Otherworld under the sanction of its ruler, Avalek, Guardian of the Gate.

What were ‘fire-apple trees’? The only magical apples that come to mind are the Golden Apples of the Hesperides, which Heracles retrieved as his eleventh labour—but the Sicilian Greek poet Stechichorus and the Greek geographer Strabo locate the Garden of the Hesperides in Tartessos, southern Spain, while the Roman author Pliny the Elder places it in modern-day Morocco. If the Isle of Avalon was the Hesperides, then the Gardenplace and the Isle of Avalon shared something else that made them unique: they both produced golden apples. The Kolbrin also says that ‘the Druthin had their seat at Innisavalon, the island of indestructible apples16. Whatever these indestructible golden fire-apples might have been, knowledge of them is now lost to us

A cosmic magnet

In their booklet describing Glastonbury’s celebrated Red and White Springs,17 Nicholas Mann and Philippa Glasson move between the geological and the metaphysical:

‘The natural and man-made features of the island created the feeling of a place set apart from the normal scope of life. It was a sacred isle… defined by a ritual boundary. The island, with no regular inhabitants, was seen as a Paradise realm, where the divine was honoured… The Tor formed a connection between the above and the below, around which earth and sky turned, and at its centre was a symbolic opening through which the traveller between the worlds could pass. From this opening flowed the two springs, one red, one white, representing a fundamental polarity in resonance with all the polarities present in the earthly realm… This is a place where the veil between the worlds, between the solar, the terrestrial and the demonic realms, dissolves; a place where the… world soul connects with the life of the individual soul to provide healing and initiation. This truth is attested by the life-changing experiences of those who come here today.’

Wellesley Tudor Pole, founder of the Chalice Well Trust, made a similar observation:

‘There are certain geographical spots or centres where the veil is thinner than elsewhere… through which Light can pass down into our human atmosphere more easily… Such spots are nearly always situated near a spring, well or fresh running water. Chalice Well is one such centre and… whatever is thought or done there, it becomes magnified and can be carried further.’

The White Spring, Wellhouse Lane, once a civic water supply, now transformed into a New Age shrine. Photos YW

A few other writers have glimpsed Glastonbury’s deeply mystical nature. The late Philip Coppens wrote on his website:

‘Just below the Tor … we need to note a small street known as Dod Lane… it is specifically its name that is important: Dead Man’s Lane. Paul Devereux has convincingly shown that the mystery of the so-called leylines was, in origin, nothing more—or less—than paths created for spiritual travel (the soul said to be able to travel only in straight lines). Hence, Dod Lane is yet another remnant from a distant past that tells us there was an ancient spirit path by which the souls of the dead passed to the other world. During excavations on the Tor between 1964 and 1966, Philip Rahtz found two burials oriented north-south, and thus unlikely to be Christian, suggesting the Tor was used for pagan burials. Noting that the path [from Dod Lane] led up to the Tor and that hills were seen as gateways to the Afterlife, it is clear that the Tor was seen as one such gateway.’18

And in The New View Over Atlantis the esoteric writer John Michell wrote:

‘The main axis of Glastonbury town, marked at its western end by the Church of St Benedict, runs eastward down the length of the Abbey and is picked up to the east of the town by a track called Dod Lane which passes over the slope of Chalice Hill. It is partly causewayed and was evidently part of a processional way to the Abbey. Its name, related to the German Tod (death), means ‘dead man’s lane’. It is a name which [Alfred] Watkins often found on leys19, and the folklore associated with it identifies Dod Lane as a spirit path.’20 21

‘From here ran the old road to the place of light where the brightwinged spirits flew freely in the place called Dainsart in the old tongue’ says the Kolbrin. Paul Devereux, in his book Fairy Paths & Spirit Roads22, mentions a place in Nemen, Russia, where there existed the tradition of a Leichenflugbahn – literally a ‘corpse flightpath’ which ran in a straight line. The name ‘Dod Lane’ marks the entrance to such a flightpath. Devereux also notes that archaeologists excavating the Sweet Track found some strange, polished yew pins similar to those found at Neolithic burial sites23. They were probably fasteners for bags containing cremated human remains—yet another indication that Avalon was an island of departure for the dead.

Over many thousands of years, Dod Lane’s spirit pathway has combined with Glastonbury’s other powerful elements ‒ the labyrinthine Tor, the Red and White Springs, the converging ley lines, and telluric forces near the earth’s surface24—to attract spiritually attuned people from all over the world like a cosmic magnet.

Joseph of Arimathea

One name enshrined in Glastonbury lore is Joseph of Arimathea. The New Testament gospels describe him as ‘a rich man of Arimathea (Matthew), ‘An honourable counsellor’ (Mark), ‘a counsellor, a good man and a just’ (Luke), and ‘a disciple, but secretly, for fear of the Jews’ (John). He was designated Decurio nobilis by Maelgwyn of Llandaff (writing c.450 AD) and by the Archbishop of Mayence, Rabanus Maurus (776-856 AD). This title, according to the writer Isobel Hill Elder, indicates that he served as an officer in the Judean or Roman Army and explains how he happened to know the Spanish-born, British-educated Governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate. Laurence Gardner, referring to the legend of Joseph as a tin-trader, proposed that Decurio might mean ‘overseer of mining estates’,25 suggesting that the term originated from Spain, where Jewish/Phoenician traders were active, with many Jewish refugees. There is good reason to believe that the Cornish mines were worked by Jewish slaves deported from Judea by the Romans after several rebellions.

The St Mawes Tin Ingot, Royal Cornwall Museum, Truro, recovered in 1812 by bargemen in the sea between St Mawes and St Just-in-Roseland, Cornwall. Dating has ranged from prehistoric to mediaeval.. Photo YW

The Kolbrin’s Britain Book contains no fewer than four different accounts of Joseph’s time in Britain. He is called ‘Joseph Idewin’, ‘Joseph, our father in faith’ and the British people’s name for him, ‘Ilyid’26. In the Kailedy gospel of John of Numa27 he is ‘Joseph of Abramatha’. The Britain Book accounts record Joseph of Arimathea arriving on the coast of Britain with a boatload of companions, his subsequent dealings with the Druids and King Caractacus/Caradew, the rocky progress of British Christianity during its first few hundred years and the Roman persecution of early British Christians. Yet every history of ancient Britain dismisses Joseph of Arimathea in Britain as folk legend. To this day, histories of British Christianity tend to start with a clumsy plonk! in 597 AD, the date when St Augustine arrived from Rome to convert the British nation.28

Aside from the Kolbrin records, evidence abounds both for Joseph coming to Britain after Jesus’s crucifixion, and for Britain being dubbed the cradle of Christianity. In 450 AD Maelgwyn of Llandaff, Lord of Anglesey and Snowdonia, recorded that ‘Joseph of Arimathea, the noble decurion, entered his perpetual sleep with his XI companions in the Isle of Avalon’. The theologian Tertullian, the Christian scholar Origen and the monk Gildas all noted the early establishment of Christianity in Britain during the early centuries AD. Four Catholic Church Councils (Pisa in 1409, Constance in 1417, Sienna in 1424 and Basle in 1434) ruled that ‘the Churches of France and Spain must yield in points of antiquity and precedence to that of Britain as the latter Church was founded by Joseph of Arimathea immediately after the passion of Christ’.29 And Polydore Vergil of Urbino wrote in his 1513 Anglica Historia [early English translation]:

‘At which time that same Joseph, (as the Evangelist Metheue witnesseth was borne in the cittey Arimathaea, and buried Christes boddie,)… cam into Brittaine, whereas bothe hee and his fellowship preaching the word of Godd and sincere secte of Christe, manie were trained to the trewe piete, and being indewed with the right saving helthe wear baptized. These men… obtaining of the kinge a little grownde to inhabit, nere unto the towne named Wells… did sowe the seade of our new religion, where at this day is a gorgeus cherche, and faire monasterie of religious menne of the order of Sainct Benet, called Glastonburie.’

Indisputable proof comes from the historian Cardinal Cesare Baronius (1538-1607), Curator of the Vatican Library. His Annales Ecclesastici a Christo Nato ad Annum, covering the first twelve centuries of Christianity, were published between 1588 and 1607 and described by the 19th-century Catholic historian Lord Acton30 as ‘the greatest history of the Church ever written’. Volume 1 includes an entry based on a previously unpublished manuscript history of Britain and a life of Mary Magdalene from the Vatican archives:

‘In that year [AD 36] the party of Joseph of Arimathea and those who went with him into exile, was put out to sea in a vessel without sail or oars. This vessel drifted, and finally reached Massilia [Marseilles] where they were saved. From Massilia Joseph and his company passed into Britain and after preaching the Gospel there, died.’ Baronius’s list of passengers included ‘Mary wife of Cleopas, Cleon, Mary Magdalene, Saturninus. Martha, Eutropius, Maximin the blind man, Lazarus, Salome, Marcella the Bethany sisters’ maid, Martial, Sidonius (Restitutus) and Joseph of Arimathea.’ (See endnote for original Latin text.31)

Portrait of Cardinal Baronius 1622-23, Museum Plantin-Moretus. (Public Domain)

The all-powerful Vatican could easily have expunged all memory of the event in order to claim precedence for the Catholic Church. But no, Joseph of Arimathea’s early arrival in Britain is recorded for posterity. The Church of England also endorses the event. In 2011, when I asked Jane Hedges, then Canon of Westminster, what the Church of England thinks of the Joseph of Arimathea story, she replied that it takes the event and date seriously. So it is high time historians took it seriously, too. Baronius’s record, to be seen in cathedral libraries throughout Britain, should dispel any notion of Joseph of Arimathea in Britain as mere folklore.

First retelling, scribe unknown

Joseph’s sea route to Britain, the Lake Village, the Hundred of Glaston Twelve Hides, the old Wattle Church

The Kolbrin’s first Joseph of Arimathea account details his sea route to Britain. Nearly all the ancient place-names can be identified:

‘In the Books of Britain it is written: Ilyid32 came seaborne in a ship of Tarsis [Tartessos, on the Spanish peninsula] from across the sea of Wicta [Sea of Vectis, now called The Solent], setting up at Rafinia [Richborough, Kent] in the land of the Wains [Land of the ancient British chariots]. From thence to the river Tarant [Trent]which flows between the Kingdom of Albany and the Kingdom of Kori [Kingdom of Korin – Cornwall], Albany being the land between the Isen [Iron-working area to the east] and the Ikta [Isca or trading town of Exeter] to the west. Passing Ivern [Charmouth] and Insels [Looe island] south of the Kathebelon [not identified33] and then past Dinsolin [St Michael’s Mount] to take water at the town where ships traded standing at the foot of the red cliff between the two white ones [Cligga Head near Perranporth?] around the extreme of the world to the northern Ikta [Isca, the trading town of Caerleon-on-Usk] in Siluria [south-east Wales, home of the Silures, a warlike tribe].

‘Here, they were unwelcome, but were permitted to take water and wood and to trade for meat and grain. Sailing thence towards the rising sun, they came to the place beyond Sabrin [River Severn]called Summerland [Somerset].’34

Left to right: 1 St Michael’s Mount/Belharia/Dinsolin, Cornwall

2 Pre-Roman slipway, wharf and quay at the northern Ikta/Caerleon-on-Usk, Newport, Wales

3 Ancient freshwater well on Roman foundation at the northern Ikta/Caerleon-on-Usk

4 Goldcroft Common, last of the nine trading commons at northern Ikta/Caerleon-on-Usk.

Photos YW

The story continues:

‘They were coldly welcomed by Homodren of the Chariots, but in the Kingdom of Arviragus they came under the mantle of the High Druid of the south whose ear was inclined towards them, for he understood full well the nature of the three-faced god. The king [Arviragus of Siluria, brother of Caractacus the Pendragon35] heard their words but did not take them to heart, saying they differed little from what was there.

‘Then were the shipborne wanderers given land over from the Isle of Departure, saying that could they live where no one else could because of the spirits, then their holiness would be established before all the people. The strangers were sorely tried by the Druids, but the spirits troubled them not. Nor did the sickness of the place come upon them, and the people wondered. They were troubled because of where the strangers were, and were stirred up by the Druthin, but the shield of Arviragus protected them.

‘Now, eastward and to the north there was a lake and between this and the Isle of Departure there was a swampland and there was a village of houses that stood out above the water, and the moonmaidens and moonmatrons who served the dead dwelt there.’36

As luck would have it, the site of Glastonbury Lake Village has survived the ages as the best-preserved Iron Age settlement in Europe. It has been twice excavated37 and its archeologist, David L. Clarke, noted that it contained areas of specialised activities and structures occupied only by women.38 A further two lake villages, known as Meare East and West, have been discovered nearby.

Detail, reconstruction drawing of Glastonbury Lake Village showing log boats arriving laden with swans, by Amédée Forestier, 1911. (Public Domain) Photo YW

Lake village roundhouse reconstruction at the Peat Moors Centre, Westhay, Somerset. Photo Martin Bodman (CCBYSA2.0)

Iron Age items discovered in the Lake Village included wooden-handled tools, ladders, wheels, baskets, jewellery, tweezers, spindles, dice and this sheet-bronze bowl, known as the Glastonbury Bowl. Photo Rodw (CCBYSA4.0)

‘Among these [moon maidens and moon matrons who served the dead] was Islass the Dreamer who was sacred to the guardian of this place. Islass was the daughter of the queen’s youngest sister39 and a holder of the king’s favour, and when she attended him she divulged her dreams. It happened that she dreamed the same dream thrice, and this was its manner as she told it to the king: “Behold, I saw a moon which had three changing faces and as I watched the changes the moon itself changed and became a sun, and within this sun was a face of a god. As I looked long on this sun, another sun appeared and such was its brilliance that the first sun appeared inferior in brightness. Then the two became one and its brilliance filled the sky. In the midst of this I saw the king and many Druthin and priests of the strangers. Then I saw a great battle sword and the brilliance faded as did the figures, and only the sword remained, from which blood dripped drop by drop. Then, too, it faded.”

‘The king took heed of the dream and gave the strangers land beside the Summerhouse of the King, which could be reached by ships. Inland from here, the gifted land extended to the tree now called the Great Oak which still stands, and thence to the hill south of the residence where Ilyid, being wearied, rested against a great stone. Beyond this was an avenue of standing trees and oak trees placed one and one, and the gifted land came up against this.

Incredibly, the last pair of ‘the avenue of standing trees and oak trees placed one and one’ still survive despite recent attempts to burn them down. They are known as ‘Gog and Magog’. These remarkably ancient oak trees off Stone Down Lane near Glastonbury Tor, which still leaf in summer, stand at the end of a pathway down from the Tor.

Gog and Magog, the Druid Oaks, off Stone Down Lane, 2010. Photo YW

It [the gifted land] extended southward to the holy vineyard which was fenced about. The fruit of these vines was small and bitter in the mouth.’40 Where the bitter grapes were located is not known41, nor is ‘the Summerhouse of the King’ known outside the pages of the Kolbrin, but the land Arvigarus gave to the strangers is well recorded.

The Hundred of Glaston Twelve Hides

This unique grant of land was recorded in a tattered and almost illegible charter shown by Glastonbury monks in 1130 to the historian William of Malmesbury, who incorporated it in his early 12th-century work De antiquitate Glastoniensis ecclesiae.42 The charter, dated 601, was a grant by a king of Dumnonia at the request of Abbot Worgret of the Isle of Yneswytrin to the monastery there.43

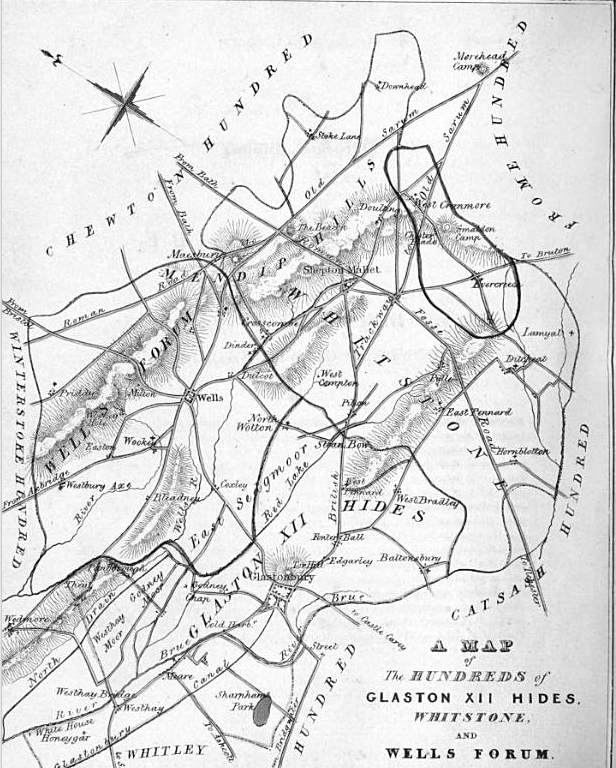

Glaston XII Hides, Phelps, William et al. Public domain

Centuries later, the land was known as ‘The Hundred of Glaston Twelve Hides’. A 1086 description44 records the land as a ‘vill’ (villa) [a rural land unit] to which the ‘islands’ of Meare, Panborough (in Wedmore), and ‘Andersey’ (Ederisage, now Nyland in Cheddar), were attached, and which included Beckery, Godney, and Marchey. Glastonbury and its six ‘islands’ were all named in King Henry I’s charter of 1121. Maps show that the Glaston Twelve Hides covered 24,610 acres/38.5 square miles. It was a privileged estate exempt from paying danegeld and was owned by Glastonbury Abbey right up to the time of the Abbey’s dissolution by King Henry VIII in 1539.

The Britain Book continues:

‘The strangers built huts for shelter on the hillside, high enough to be free of the tides. They settled down and learned the language, though Ilyid and two of the women spoke it strangely.

‘The words of the strangers fell on deaf ears, for the people were content with the gods they knew and did not wish to weary their minds with the words of the new ones. When the strangers gathered in praise of The One True God the tribesmen stoned them and shouted abuses, but Ilyid perservered and while later the people still would not believe that the God of whom he spoke was more powerful than their gods, they would sit around and listen to his stories.

‘Now, when the strangers were granted the land, the Druthin disputed this with the king and said that they wanted a divine sign that their gods approved. Ilyid said, “Give me but half a year”. At the witnessing of this the Druthin set up a holistone and Ilyid struck his staff into the soil to mark the covenant.

‘The following Eve of Summer there was a gathering and it was found that a small green shoot was coming up from the ground beside the staff, which was an offshoot of the staff. The king decreed that this was a sign that the land accepted the strangers, but these took it as a sign that what they taught fell on fertile ground and would take root.’

This miraculous sprouting from a wooden staff has become the stuff of legend. The ‘Glastonbury Thorn’ or ‘Holy Thorn’, unlike other British hawthorns, flowers twice a year, in winter and in spring. Trees in the Glastonbury area have been propagated by grafting since ancient times, and descendants of the now-vandalised Holy Thorn on Wearyall Hill can be seen around the town. Records speak of Holy Thorn cuttings being sent as Christmas gifts to King Charles I and Charles II. The tradition was re-established in 1929 and since then, every Christmas Day, a budded branch from the Holy Thorn has been delivered to the reigning monarch. The Glastonbury Thorn has been depicted on Christmas postage stamps, and Elizabeth von Arnim beguilingly echoes its theme at the end of her 1922 novel The Enchanted April, brought to the screen in 1991 as Enchanted April starring Joan Plowright.

‘Here, the strangers, now called the Wise Ones, were free from the yoke of Rome and from the intolerance of the Jews. They were not subject to immoral customs and were among the right-living people, simple but pure in mind and body. Close by was a place for trading in metals, slaves, dogs and grain. Here, Ilyid built himself a house unlike any others, for it was square and in two parts, more stone than timber. This place was called Kwinad.’

The ‘place for trading in metals, slaves, dogs and grain’ would have been where the Market Cross now stands in Glastonbury town centre.

Glastonbury: Market Cross by Mr Eugene Birchall (CCBYSA2.0)

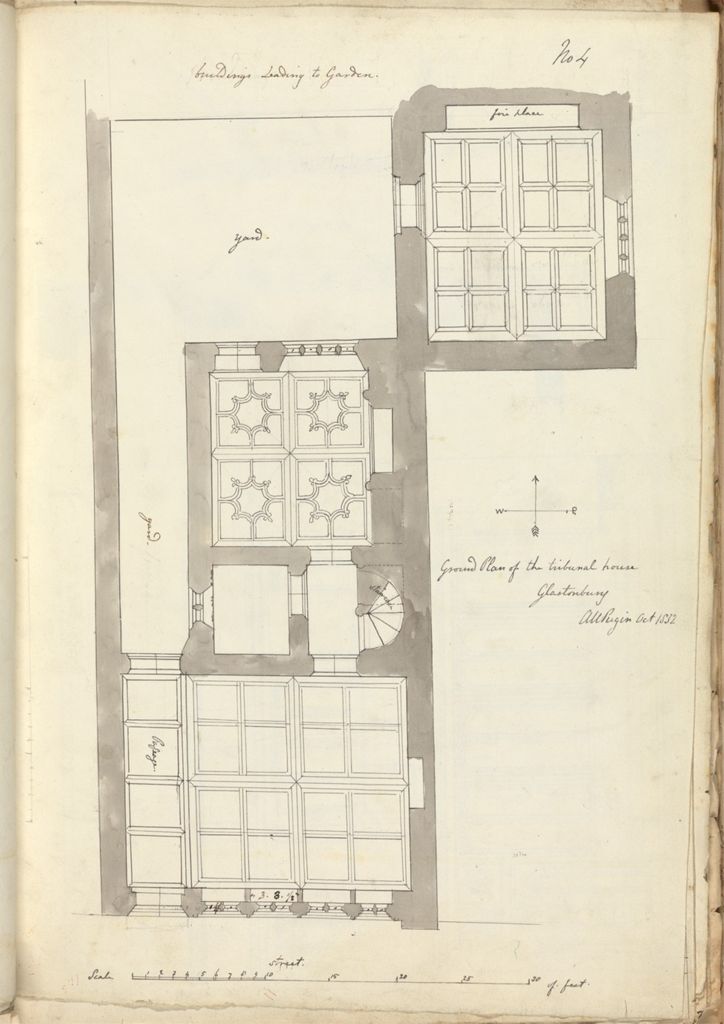

Joseph’s house sounds Roman in design and would have looked distinctive to Britons used to thatched timber roundhouses. The oldest building in Glastonbury High Street is the Tribunal, just a hundred yards from the marketplace. The current 15th-century structure stands on the site of a 12th-century wooden building. One can’t help wondering what might have stood there in even earlier centuries, since a basic floor plan of 1832 shows several square areas which at some point were joined together.

Tribunal, Glastonbury High Street, by Bill Harrison CCBYSA2.0)

Tribunal: Ground Floor Plan, 1832, by Augustus Pugin. CC0)

The Wattle Church

The Britain Book continues:

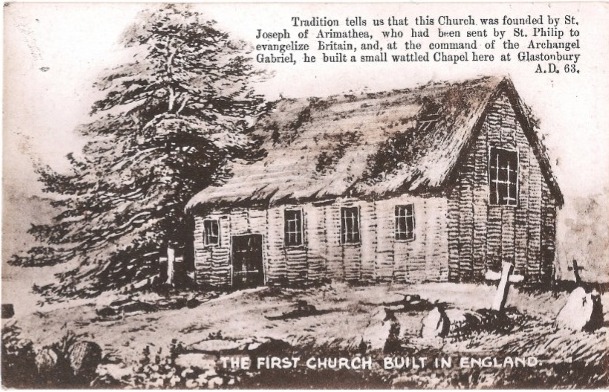

‘Here, on twelve portions of land, the wise strangers dwelt in peace and they built a church which was a full sixty feet long by a full twenty-six feet wide. At one end was a statue four feet high, carved from a beech trunk. The roof was thatched with reeds, after the manner of the Britons. The walls were of wicker overlaid with plaster of chalk and mud.45

‘Here, in this holy place, under the direct guidance of God, our father founded the first church in Britain. It is said it was not built by human hands, which is true, and from here shall come that which will be the salvation of mankind in the years to come.’46

Citing ancient records, William of Malmesbury stated in De antiquitate Glastoniensis ecclesiae that ‘the church at Glastonbury did none other men’s hands make, but actual disciples of Christ built it… The church of which we speak is commonly called by the Saxons the Old Church on account of its antiquity. It was the first formed of wattles, and from the beginning breathed and was redolent of a mysterious divine sanctity which spread throughout the country. The actual building was insignificant, but it was so holy. Waves of common people thronging thither flooded every path; rich men laid aside their state to gather there, and men of learning and piety assembled there in great numbers… The resting place of so many saints is deservedly called a heavenly sanctuary on earth.’

Here, Joseph and his companions are called ‘wise strangers’ ‒ a phrase echoed in Latin accounts as quidam advanae, ‘certain strangers’, later anglicised into ‘Culdees’.

Nothing remains of the wattle church ‒ known as the Vetusta Ecclesia or Ealde Chirche ‒ because it was completely destroyed in the 1184 Glastonbury fire, but William of Malmesbury’s record is valuable for quoting earlier written testimony to the existence of a church in the 2nd century AD.

Artist’s impression of how the wattle church might have looked, postcard R. Wilkinson & Co., Trowbridge, early 20th century (?). Photo YW

The Kolbrin’s first record of Joseph ends by saying:

‘Ilyid is buried outside the forked path before the church, and on his tomb was written, “I brought Christ to the Britons and taught them. I buried Christ and now here my body is at rest…”’

The first Joseph of Arimathea account ends with the words:

‘Here, in this holy place, under the direct guidance of God, our father founded the first church in Britain. It is said it was not built by human hands, which is true, and from here shall come that which will be the salvation of mankind in the years to come. Here was the resting place for the souls of the dead, where they received their last sustenance before passing through the glass wall. From here ran the old road to the place of light where the brightwinged spirits flew freely in the place called Dainsart in the old tongue.’

This extraordinary passage combines Glastonbury’s ancient function as a departure point for dead souls flying through the glass wall to the Otherworld with a new role: Glastonbury was to be Britain’s first church, fusing Druidic beliefs with a new faith, ‘the Way’.

Second version, written by Aristolas

The Chief Druid and Joseph of Arimathea debate their beliefs

‘This,’ says the Britain Book, ‘is an account of the coming of certain Wise Strangers to the sea-girt realm of Britain. Taken from the Books of Britain and re-written into the appendices to the Bronzebook. This being that part safeguarded by Rowland Gasson.

‘After our Lord died, having been hung on the cross outside the city walls of Jerusalem, Joseph of Abramatha took Mary, the mother of Jesus into his home until John could make suitable arrangements. Then he was called Guardian of the Lady, which title became confused in Britain with that of Guardian of the Sacred Vessel.

‘Aristolas wrote these things in the Sacred Island…47

‘Joseph, our father in faith, came across the storm-tossed seas to the place called Balgweith, and from thence to Taishan where he met the envoy of the king who was sorely troubled. For the Chief of All Druthin, called Trowtis, was away at the meeting place of his god, where he came in a wondrous way every nineteen years. There, the ceremony lasted three moons.’48

Diodorus Siculus wrote of this nineteen-yearly event: ‘The account is also given that the god [Apollo] visits the island49 every nineteen years, the period in which the return of the stars to the same place in the heavens is accomplished; and for this reason the nineteen-year period is called by the Greeks the “year of Meton”. At the time of this appearance of the god he both plays on the cithara and dances continuously the night through from the vernal equinox until the rising of the Pleiades, expressing in this manner his delight in his successes.‘50

From this, it emerges that alongside the powerful king, the Druids wielded enormous influence. The Island of Glass was an important religious centre in Britain ‒ perhaps the most important, since Trowtis, the Chief Druid, was based there, with his daughter Islass the Dreamer, daughter of the queen’s youngest sister and a favourite of the king, living and serving as a moon-maiden at the women’s settlement of Glastonbury Lake Village.

The Britain Book continues:

‘When Trowtis [the Chief Druid, father of the moon-maiden Islass] returned, he met Joseph at the place now called Henmehew because of the strange tree [the Holy Thorn?] that grows there [Wearyall Hill]. The Druthin held a feast of welcome in the place called Nematon [a sacred Druidic space in a sacred grove], which is below the great hill [Glastonbury Tor]. The Chief of All Druthin washed his face, his hands and his feet, then a white goat was led out and sacrificed on a four-horned altar. Trowtis washed his hands again and made an offering of salted barley cakes and gave some to Joseph, called Ilyid by the people here.

‘Then the goat’s thighs were burnt on the altar while a lesser priest mixed the sacrificial blood with water and black wine. Then barley cakes and a chalice containing the blood, wine and water were passed through three sacred horns before being given to the chiefs present. Then youths danced around the fire over the sacrificial pit. ‘Then priests of a lower order prepared tables for a feast while the common people sat around on logs made smooth at the top. The sacrificial beast, having been first offered to the gods of this place, was eaten by the common folk. All except the liver, which, being the seat of blood and life was kept for the diviners. These found that the right wing of the liver was broken, so they prophesied that no enemy would enter the land.

‘Now, the king called together a great conclave of the people, and the Druthin were there. The king said to our father, “Speak now before the people. Tell us of your ways and we will judge whether they be worthy”. Joseph spoke a tongue understandable to these people, but he spoke slowly and not after their fashion.’

Joseph spoke a form of Brythonic, suggesting close contact with Britain over the years.

‘Our father said, “As the light came first and called the eye into being to see it, so it is with God who is the already existing light. The heart does not create the thought, but the thought produced the heart. This, so it could manifest, for the heart is created to serve thought in the world of effects. The world of causes lies in another kingdom”. The Druthin said, “The light we know and have, these things are not strange to us. All light comes from an original crystal which is always virgin, and we say the behaviour of light is the fore-ordained symbol to man”.

‘Joseph, our father, said, “I have not come to batter down your house of hope, for it has many pleasing features, even as ours. So let us not disagree but take the best from both and, discarding what is less good, fashion something of value to all. Let us weigh one thing against the other, rejecting that which less clearly shows the way”.

‘The king said to the Chief of All Druthin, “Do we not have the source of light in a grail egg? ” The Druthin replied, “The sun shines not and the Esures (servants of Light) will not come without the presence of the Great Gleamer which provides their sustenance. There can be no incarnation of light on Earth unless there be, behind it, a greater light”.

‘Joseph said, “When I was shipbound I had a vision of God, the eyes of my spirit were opened and I saw Him in all His glory. Then I understood that there was no difference between the nature of His Spirit and the spirits of men, only that His was of an infinitely greater purity. This I knew for sure: God and man are of the one essence. I knew we are all rays of the One Light, sparks from the One Flame. Yet the flame is not the fire, for what flame can call itself into being?”

‘Joseph said, “If fire can be contained in wood, to leap forth when two pieces are heated through rubbing together, yet remain hidden within the wood, then surely it can be so with the soul within man”.

‘The Chief of All Druthin said, “Often have I thought on this. All men are alike in nature and all aspire to the same goal. All seek to make the same journey’s end, only the route differs. Therefore, let us not argue whether men should follow your road or mine, but find between us a path better than either”.

This discussion concurs with John Michell’s findings: ‘The great mystery behind early Christianity in Britain is how the first missionaries managed to persuade the chiefs, nobles and Druids, the established hierarchy of highly traditional societies, to lead their people in converting to the new faith of Christ. Certainly, there was opposition referred to in several of the early saints’ legends, but there is no record of violence and bloodshed. Contests between the rival men of religion, Druid and Christian, took place on a professional level, as trials between rival magicians.’ And, ‘This transference from pagan to Christian religion of mystical lore and number symbolism is in accordance with what Celtic scholars have long asserted, that the laws, rites and doctrines of the early Celtic Church were basically the same as those of the Celtic Druids.’51

The Britain Book continues:

‘One priest said, “What of the worlds within the ever-moving circles?” Joseph replied, “The hidden worlds are numbered as sands on the seashore. If a man concerns himself with many things, he benefits none and derives no benefit himself. Let us concern ourselves with this world first”.

‘The Druthin said, “Who can change the natures of men, for these are fixed by the gods”. Joseph answered, “All things can be changed, but not always for the better. Change and life are inseparable”.

‘Joseph went on to say, “Because you are folk who work the land, bringing it to fruitfulness, you are not to be despised. Let the newcomers with their armed might [the Romans?] say as they will, you are workers with God. Were not the Sons of God also called the Sons of the Plough? Did they not fight against the Sons of Men who were hunters eating raw flesh like the beasts and worshipping serpents which crawl on their bellies? Always there have been some who worship things of insensitive wood and stone, grovelling in the dust at their feet, and those who worship the highest they can see, the sun and the stars. Others reach out even beyond these”.52

It emerges that both Joseph and the Chief of the Druids knew about past conflicts between the agricultural and pastoral Sons of God known as ‘Sons of the Plough’ and aggressive hunter-gatherer Sons of Men descended from mismating between engineered Sons of God and earth-born hominids (see articles ‘Where We Humans come from’ and ‘The Kolbrin On The Sons Of God and Daughters Of Men’).

The Britain Book continues:

‘One of the Druthin asked, “What know you of the Eye of God in men?” Joseph replied, “What is written in the heart is the Eye of God in men, this sees everything. Knowing right from wrong it puts things in instant perspective. Men in whom this eye is closed are little better than the beasts of the field and forest. I come as one who opens the eyes of such as these”.

‘In the beginning the king had listened in silence and was tolerant, because he felt he could indulge these strangers. Now, as he saw that their teachings might prevail, he became angry and unreasonable, as it happens in instances such as these. He said, “Who gives you authority to speak in this manner? Who sent you and do you come to spy on us? To whom do you make report?”

‘Joseph said, “Know this, great king. I am a servant of The Great God of Light. I am sent in order to build a church here where it will serve your people well. I will establish a place of light unto them. I come to teach the perfect commandments. Ask among your own about me, for I am not unknown to them. I have no human teacher from whom I learned the wisdom from whence I got these things. I lived in the light of Christ but learned tardily. Then I had a message from God Himself, ‘Go preach to those who dwell at the edge of the Earth’ “.

‘Ask among your own about me, for I am not unknown to them.’ Here is further evidence that Joseph was already known to the British people ‒ more on this later.

‘The king said, “How comes it that these things have been revealed to you, while the same God who reigns here has not revealed them to us, even though we were the lords of this land? Are you a man of significance this side of the wide waters?”

‘Joseph answered, “Those who are established in The God of Light need no mentors and they take pride in their insignificance, for it is said, ‘The first shall be last and the last first. The lowly shall be raised up and the haughty cast down’. We do not seek after gold or worldly possessions. Of myself I have no power, but I have power from God. It is God who commands and it is He who makes a true man of God.”

‘There was much talking and long discourses on the nature of God, and the Druthin challenged Joseph to produce Him, saying, “Though you decry our images, yet we do have likenesses of our gods while you lack even these. Your words are mere puffs of wind”.

‘These things and more were said, and the Druthin believed, but tardily. Then, at the midsummer festival the Chief of All the Druthin collapsed on the processional walk, denying himself the reviving draught prepared by Islass his daughter. He died in the arms of Joseph our father. It was he [Joseph] who received the moon chalice and the light of Britain. The Druthin held the secrets of the Great Temple of the Stars [Stonehenge? Katherine Maltwood’s Temple of the Stars?], and theirs was the royal isle [Anglesey] in the Kingdom of Kevinid [Gwynedd].’53

The religious discussions were clearly long and difficult. Eventually, ‘the Druthin believed, but tardily’.

Third Version, written by the scribe Elfed

The Romano-British royal connection and King Caradew/Caractacus

This short account gives some fascinating historical detail:

‘Aristolas taught that Ilyid had been one who commanded with the ships of Rome, but was not without ships himself. So it was that when Jesus went down to the Western Sea of the Jews, which is not the Sea of the Setting Sun, He being one skilled with His hands, worked on them. Jesus was brawnily built and not one to take money without labour.

‘Jesus, our Master, Light of our Life was hung on the shameful cross in His twenty-seventh year, this being the one thousand and ninety-ninth year of Britain, in the reign of Tiberius, ruler of the Roman lands to the east.

Within a year, Ilyid and others departed from their homeland shore by ship, and though this was de-masted in a heavy storm it made safe haven in Sankel. There, he and his son were joined by several other holy persons. They tarried awhile before crossing to Laidlow, from whence they took a ship to Tarsis.’54

‘Tarsis’ was Tartessos/Tarshish, a region at the mouth of the Guadalquivir river in what is now Andalusia, Spain, and was famed for its Phoenician harbour city where gold, silver and precious exotic commodities were traded, including tin mined in Cornwall.

The circle of Roman might

‘In the year of Britain one thousand one hundred and twelve, our father came from Rome with others, because of the decrees of Claudius, ruler of all the Romans to the east, seeking refuge beyond the oppression of Roman might where the true light could burn undisturbed. But the circle of Roman might spread ever wider, like a thrown fisherman’s net.

‘Thirteen years after our Master was hung on the cross, the Romans came to the fair land of Britain, and the might of their legions prevailed over the brave Caradew [Caratacus], great battleking of all the Britons. He was the leader of fighting men such as will not be seen again. He was carried off, betrayed by an irrational woman55, an honourable peace offering to appease the argument of might, together with the British fount of knowledge and wisdom. With him went the allwise Fran, being held in honourable captivity until returned to the land of light at the intercession of our father, for those whom he befriended had not forgotten him. For Ilyid taught that the greatest wrong man can commit against man is the betrayal of a friend.’

When, in 50 AD, the betrayed battleking Caratacus/Caradew was led in chains to Rome, his fiery speech in defence of his kingship and country so impressed the Roman Senate that they commuted his death sentence to seven years’ free custody in Rome with his family. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, his words, as recorded by the writer Cornelius Tacitus and later translated into English56, were committed to heart by every self-respecting British schoolboy.

Caratacus/Caradew and his large household are said to have lived at the Palatium Britannicum or Britannic Palace on the Mons Sacer in north-east Rome.

The Britain Book goes on:

‘Now, the daughter of Caradew was Gladys, red-haired, blue-eyed and slim, who married Pudens, Commander of the Legions, beloved of Paul the Martyred in God, who died in the one thousand one hundred and thirty year of Britain. Lein, son of Caradew, brother of Gladys, being the first Christian in Rome.’57

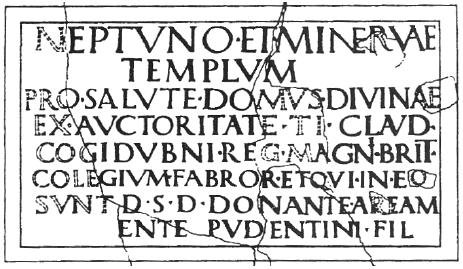

Pudens, Commander of the Legions, can be identified by the Pudens Stone, a 1st-century Roman marble inscription found in Chichester in 1723. It reads: ‘To Neptune and Minerva, for the welfare of the Divine House, by the authority of Tiberius Claudius Cogidubnus, Great King in Britain, the college of artificers and those therein erected this temple from their own resources […]ens, son of Pudentinus, donated the site.’

Reconstructed Pudens Stone, Professor Dr. J.E. Bogaers (Public Domain)

In The Drama of the Lost Disciples58, George F. Jowett identifies the ruins beneath the Basilica of St Pudentiana in the Via Urbana, Rome as the bath-house59 of Aulus Pudens60. The centurion has also been identified in Italy as a Roman Christian, Saint Pudens.

Basilica of Santa Pudenziana, Rome. Photo globustut.by (CCBYSA4.0)

The Britain Book speaks of ‘Lein, son of Caradew, brother of Gladys, being the first Christian in Rome’. This is the same Linus who is addressed as Gladys/Claudia’s brother in the New Testament, in 2 Timothy: ‘Do thy diligence to come before winter. Eubulus greeteth thee, and Pudens, and Linues, and Claudia, and all the brethren.’61 It is worth noting that Linus – and not the apostle Peter – is described in an early record as the first Bishop of Rome62.

Fourth version written by Abaris, a Druid-Christian convert

Persecution of early British Christians, decline and restoration of the first church at Glastonbury, mention of King Cymbeline and Queen Boudicca

Abaris begins, ‘I write in terrible times. My people have been driven to black despair and the most cruel of foes has taken our fair land…’63

The Romans have arrived in Britain. Abaris describes how his fellow Christians have been oppressed by the might of Rome:

‘The culled-out servants of The High God entered the arena of vile entertainment, like children before their teachers. They were thrown into the path of the lions. Some they equipped with weapons and forced to fight with bears. Women were scented with the smell of heat-angered beasts and children stood frozen with fright. Their bodies were shredded like the paper of Egypt. They moaned pitifully, like oxen awaiting the slaughter and their children were murdered before their eyes. They were raised up by thongs on the wrists, their feet pressing on thorns or on heated plates, or over small fires. Many were thrown into prisons to die of hunger, thirst and cold.’64

The early Christian household of Pudens and Gladys (who was thought to have been adopted by the Emperor Claudius and renamed Claudia) included a daughter, Pudentia. Pudentia devoted her life to bringing back the grisly remains of British Christian martyrs from the Colosseum and burying them at the Britannic Palace. The Basilica of Santa Pudenziana is named after her.

Abaris goes on to speak of Joseph of Arimathea:

‘Joseph Idewin and his brave band came to flowering Britain three years after the death of Jesus. He converted Gladys65, sister of Caradew, who married a Roman, and her sister Aigra who was the wife of Salog, lord of Karsalog. After landing, he and his band passed through an avenue of oaks and standing stones. They first built huts over against the holy vineyard where the fruits were bitter.’66

White Stone Lane, which runs beside the Tor near the surviving Druid oaks Gog and Magog, may well mark where the standing stones once stood.

The Britain Book continues:

‘After all the saints had gone to their rest, the first church and its surroundings became a wild place, a refuge for wild creatures. Then, as the land remained holy, saints came from Gaul, who restored it, and one was Fairgas [Fergus] the Briton, who had served at this place as a youth. Idewin [Joseph] was buried in a shirt of fine linen which he had worn when burying Jesus and which was stained with three spots of blood on the chest. He was buried by the two-forked cross. The saints had lived in twelve huts around a never diminishing well at the foot of the holy hill.’67

Christianity virtually vanished when Joseph and his companions died. But ‘the land remained holy’, as it had been even before Joseph’s arrival, and more converts arrived in Britain to restore the ruined church and its surroundings. The ‘never diminishing well at the foot of the holy hill’ where ‘the saints’ lived in huts is now known as Chalice Well Garden ‒ a name it may well have carried for many hundreds of years68 based on a legend that Joseph kept the Holy Grail in a hollowed-out space beneath the well. There is a space under the well which has been rebuilt several times. Excavations near the Well in 1961 uncovered several dozen upper Palaeolithic/Mesolithic flints and a shard of Iron Age pottery; and according to John Michell, ‘traces have been found of a former community of anchorites, commemorated until recently in the name of a nearby inn, The Anchorage.’69

The record continues:

‘Joseph Idewin was related to Avalek whose kingdom bordered that of Arviragus, through Anna the Unfaithful. He converted Claudia Rufina, the daughter of Caradew previously called Gladys, who married Pudens, a Roman, and had a daughter Pudentia. In his twenty-eighth year, Caradew was betrayed to the Romans by Arisia, queen of Bryantis70. He married Genuissa, daughter of Claudius, to bind the peace agreement. The name ‘Caradew’ means ‘filled with love’, but he preferred to use a warrior name.

‘Gladys, sister of Caradew, married Aulus Plautius, a Roman commander. Caradew held an estate in Siluria and he was made warchief when Guiderius, son of Kimbelin [Cymbeline] was slain by a slingshot, near the river Thames. In the year 59 of our Lord, the British rose up under Woadica [Boudicca], the horsefighter, who died nearly three years later when Gulgaes became warchief.’71 72

One final surprise: Joseph of Arimathea was related to British royalty. No wonder he spoke Brythonic, albeit with a strange accent. No wonder he was welcomed and given land by the King of the Silurians to whom he was related.

Here the records end. Nowhere is the name ‘Glastonbury’ mentioned, but the Isle of Glass and Isle of Departure resonate throughout. And however unlikely a place it may seem ‒ there are no soaring pillars and pediments, no clusters of scholars, none of the dignitas found in most world-renowned sacred sites ‒ yet for those with twinsight into the Otherworld, Glastonbury and its Isle of Avalon will forever be a place of enchantment.

Glastonbury Tor. Photo Eugene Birchall (CCBYSA2.0)

The author welcomes correspondence with readers via [email protected]

Kolbrin text courtesy of The Culdian Trust.

References

1 Houses of Benedictine monks: The abbey of Glastonbury, A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 2, ed. William Page (London, 1911) originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1911 https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol2/pp82-99; Glastonbury : the historic guide to the “English Jerusalem”, Charles Latimer Marson (Ulan Press, 2012)

3 The Celtic Books can be bought separately from the Egyptian Books of the Kolbrin as a US paperback entitled Celtic Books of the Coelbook: the Last Five Books of the Kolbrin Bible, Marshall Masters, Janice Manning (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2006)

4 Britain Book 1:13-18

5 Britain Book 1:10

6 Book of Creation

7 Book of Creation 5:26

8 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anunnaki

9 Book of Creation 5: In the beginning

10 Book of Creation 2, The Birth of Man

12 Natural History XXXVI, 199, Pliny the Elder

13 Book of Origins 1:19

14 Ibid.

15 Britain Book 5:21

16 Britain Book 5:15

17 Avalon’s Red and White Springs: The Healing Waters of Glastonbury, Nicholas R, Mann and Philippa Glasson (Green Magic, 2005)

18 ‘Glastonbury: England’s Oldest Sacred Landscape’6, Philip Coppens, https://www.eyeofthepsychic.com/glastonbury/

20 The New View Over Atlantis, John Michell (Thames & Hudson, 1986)

21 https://normalforglastonbury.uk/dod-lane-to-the-tor-tree-walk-by-matt-witt/

22 Fairy Paths & Spirit Roads: Exploring Otherworldly Routes in the Old and New Worlds, Paul Devereux (Vega, 2003)

23 Ibid.

25 The Bloodline of the Holy Grail, The Hidden Lineage of Jesus Revealed: The Hidden Lineage of Jesus Revealed, Laurence Gardner (Element Books, 2009)

26 A place called Llanilid/Llant-Ilid in Glamorgan, Wales may well recall the name Ilyid.

27 See note on the Kailedy in chapter The Kolbrin’s Underlying Story

28 See A History of Christianity, a 2009 British TV series presented by the ecclesiastical historian Diarmaid MacCulloch, Professor of the History of the Church at the University of Oxford.

29 St Joseph of Glastonbury, Lionel Smithett Lewis, 1955

30 He famously wrote, ‘Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely’.

31 ‘Hac ipsa dispersione Ananias discipulus profectus Damascum, collegit Ecclesiam. Insuper colligere possumus, hoc quoque tempore Lazarum, Mariam Magdalenam, Martham, et Marcellam pedissequam, in quos Judaei majori odio exardescebant, non tantum Hierosolymis pulsos esse, sed una cum Maximino discipulo, navi absque remigio impositos, in certum periculum mari fuisse creditos; quos divina providentia. Massiliam tradunt appulisse, comitemque ferunt ejusdem discriminis Josephum ab Arimathaea nobilem decurionem, quem tradunt ex Gallia in Britanniam navigasse, illicque post praedicatum Evangelium diem clausisse extremum’.

32 Joseph of Arimathea

33 Kathebelon might have been what is now called Pendennis Point. The name comes from the Cornish pen meaning ‘headland’ and dynas meaning ‘castle’ or ‘fort’. The earliest mention of a defensive structure on the point are the remains of an Iron Age Cliff Castle (Hals, 1750). This castle would have been built around 800 BC but no trace of it can been seen today. Reports indicate that it once consisted of three earth, stone and turf-covered embankments that would have cut off and protected the headland from the mainland.

34 Britain Book 1:7

35 Bloodline of the Holy Grail, Laurence Gardner (Element, 1996)

36 Britain Book 1:10

38 Models in Archaeology, David L. Clarke (Routledge, 2016)

39 Islass was also the daughter of the Chief Druid, as the Britain Book later tells us.

40 Britain Book 1:8-13

41 In 1375 John of Glastonbury spoke of ‘Panborough, which is vine-bearing land’ and Richard Bere (c.1493-1524), Abbot of Glastonbury wrote that the fields adjoining Glastonbury’s Wearyall Hill were vineyards ‒ but these would most likely have produced wine grapes.

42 https://www.glastonburyantiquarians.org/site/index.php?page_id=214

43 Cf. Gale, XV Scriptores, 308.

44 See A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 9, Glastonbury and Street https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol9

45 Britain Book 1:13-18

46 Britain Book1:19-21

47 Britain Book 4:1-3

48 Britain Book 4:6

49 The island was called Hyperborea and was thought to have been a far northern part of the known world.

50 Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica, LCL 303: 40-4

51 New Light on the Ancient Mystery of Glastonbury, John Michell (Gothic Image Publications, 1990)

52 Britain Book 4:6-19

53 Britain Book 4:20-26

54 Britain Book 2:7

55 Cartimandua/Cartismandua (reigned c.43- c.69 AD), queen of the Brigantes, a tribe in northern England and known through the writings of the Roman historian Tacitus.

56 The Annals, Cornelius Tacitus, transl. Alfred John Church, ed. William Jackson Brodribb https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0078%3Abook%3D12%3Achapter%3D37

57 Britiain Book 2:8-10

58 The Drama of the Lost Disciples, George F. Jowett, Covenant Publishing Co. Ltd (2009)

59 The remains of the Roman bath-house can still be glimpsed through a grille at the side of the Basilica.

61 2 Timothy 4:21

62 Apostolic Constitutions, Book 1, chapter 46, written 375-380 AD.

63 Britain Book 5:1

64 Britain Book 5:5-6

65 Confusingly, both Caradew’s sister and his daughter were named ‘Gladys’.

66 Britain Book 5:19

67 Britain Book 5:19-20

68 As early as the 1770s a survey map clearly shows the present Chilkwell Street named as ‘Chalice Well Street’, suggesting that the Well was referred to as ‘Chalice Well’ long before Tudor Pole secured the site for posterity in 1959.

69 New Light on the Ancient Mystery of Glastonbury, John Michell (Gothic Image Publications, 1990)

70 This is the queen described as ‘an irrational woman’ in the Third Version of the Joseph story: Cartimandua/Cartismandua (reigned c.43- c.69 AD), queen of the Brigantes, a tribe in northern England and known through the writings of the Roman historian Tacitus.

71 Britain Book 5:21-22

72 Kimbelin/Cunobeline/Cunobelin was a pre-Roman British king c.AD9-c.40. His name means ‘Strong as a Dog’.

“King” Henry VIII was a fat serial killer who destroyed the best stuff in the island he was born owning. Fuck that guy.

The Kolbrin is incredibly mysterious. I wish its custodians could furnish more details of its provenance. Either it is simply good resonance (like Tolkien, Cayce, etc) or there is a 3D tradition there and if so surely it is traceable?

Alas, in the 13 years I’ve been investigating the Kolbrin, there has been no provenance to trace. Provenancially nothing, but circumstantially it ties in with so many documents, stele, events, DNA findings and archaeological discoveries that gradually the evidence is mounting in favour of its core authenticity. And yes, there is a book on the way.

It reminds me of the Oera Linda book, a similar folk record also appearing for the first time in the Romantic era (19th c) but purporting to be a copy of stuff written centuries and millennia ago, passed down in one family (apparently, they didn’t share it until modern times – odd and unlikely). Again, references to famous world events (eg Christ, Genghis Khan, etc), but no way to prove these weren’t simply composed using available reference materials of the decades preceding the first publication or sharing. Would love to be proven mistaken though, the Celtic records must have been vast and beyond ancient, hopefully even more await discovery.

On the one hand, who cares, because as Tolkien and Cayce have shown, you can still be right using fantasy and daydreams (cf. Hobbits (homo floriensis) having large feet, discovered decades after Tolkien’s death, in Indonesia. He invented that specific feature of big feet for his kids’s bedtime story, and there it was, 50,000 years ago in people three feet high on Flores only found 20 years ago). So, hoax away, maybe more real discoveries will result? It’s not like Gobekli Tepe was an academic prediction. It was farmers tripping over ruins nobody had ever kenned. Literally the oldest ruins on Earth, people tripping over them since bloody forever, but nah. Missed it. Wankers.

Even if the Oera Linda and Kolbrin are hoaxes, albeit benign ones meant to represent or simply hold a place for otherwise lost lore that “feels like it should be there” (like Middle Earth clearly does, even for Asians, despite being based entirely on Northern European lore), then maybe a few more good Oera Lindas Kolbrins and the like will see us into more, and even more betterer, similarly overdue discoveries.

On the other hand, if either book’s custodians had some kind of information about how it was kept for so long without anyone ever knowing until modern times despite being known about (and no doubt enthused in, and cultivated) by its own group of keepers for ages and ages, literally from the stone age through the bronze and iron ages roman medieval and now, as is the official yarn for both, pretty much, then surely there is at the very least the current manuscripts as physical copies, and what is known about those? Paleography and so on. The paper, ink, can all be tested. The language can be analysed. The contents can be ratified rationally quite aside from their irrational value as inspiration or whatever.

So it doesn’t actually matter if it is literally what it is being presented as, it can still matter and it can still be absurdly accurate (like Cayce and Tolkien), and ahead of left-brain methods like academia, that missed Gobekli Tepe and Hobbits until a century after their discovery in “fiction”.

However, something that can be nailed down as an ancient text, and not an ancient memory in modern text, would have its own virtue. Otherwise it would function as a “cool maybe” unless it can predict things we discover after its publication. But then, stuff not only keeps getting older as Graham says, it also keeps getting weirder and weirder, and changing. All the bloody time. So today’s proof might be tomorrow’s bad science or vice-versa. Maybe fantasy is both safer and more efficient for scientific purposes.