Note from the Author:

The enigmatic Kolbrin contains, alongside its Celtic records, six ancient Egyptian books, the remnants of scrolls written or copied by scribes from much earlier writings, whose provenance has not yet been proven. Most people dismiss the books as forgeries. I am convinced that their core material is genuine.

Ancient Egyptians, so the orthodox wisdom goes, were not the greatest seafarers. Pharaoh Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple walls at Deir el-Bahari portray trading ships that sailed to the legendary land of Punt, but to date little evidence of seaworthy vessels has been unearthed. And although one Ancient Egyptian tale describes a ship with dimensions of 120 x 40 cubits/180 x 60 ft/55 x 18m)i, the biggest boat ever excavated – Pharaoh Kufu’s solar ship at Giza, designed for his afterlifeii– would not have lasted long on the high seas.

Pharaoh Khufu’s solar ship at Giza.

‘Gizeh Sonnenbarke BW 2’ by Berthold Werner, CCBYSA3.0

Excavations at Berenike/Baranis, an ancient port on the west coast of the Red Sea 260 km east of Aswan, have revealed there was trade between Egypt, India, Africa and China in Roman times between approximately 250 BC and 250ADiii. But what about the Ancient Egyptians in earlier times? Did they cover such distances?

While discussions rage over Australia’s Gosford Glyphs – did Ancient Egyptian ships go to Oz?iv – and whether cocaine/nicotine traces on a 21st-Dynasty mummy prove the Egyptians were in Americav, the mysterious Kolbrin sits silently on a chapter recording three Egyptian sea voyages, two of them surpassing in scope anything discovered by mainstream scholars. It tells of voyages to ‘the Islands of the Outer Seas’ and mentions the magical name Ophir – a name recorded only in the Old Testament as the location of King Solomon’s goldvi and immortalized in John Masefield’s poem Cargoesvii. The Kolbrin not only lists Egypt’s exports to the Land of Punt, details the dimensions of a Punt trading vessel, and suggests that the Land of Punt stretched over an area far larger than is currently thought, but it also records Egyptian voyages much, much further to the islands of distant Ophir.

As always in the Kolbrin, names in the text are skewed – a few so frustratingly obtuse that they cannot be positively identified; but there is sufficient solid identification to offer a surprising perspective on Egyptian maritime capability.

An Early Egyptian Scroll

Chapter 24 of the Book of Manuscripts is a letter entitled ‘An Early Egyptian Scroll’. The sender’s and recipient’s names are not given, but the letter is addressed to ‘A craftsman in the words of God and a teacher of writing. The Grand Scribe of his Lord, a faithful servant of a noble master. Beforetimes Keeper of the Royal Writings, whose father’s father’s father was Chief Overseer of the Great Pharaoh. Follower of the Wise One whose wisdom and goodness reveal the Divine Essence. Son of the Master of the Secret Ceremonies, Captain of craft in the journey to the Islands of the Outer Seas. May you live forever in prosperity and health, and may life bestow its favours upon you. May the Protecting Spirit spread its wings over you and may your rewards hereafter exceed your expectations. May your servants dutifully transport sand for your fields and may your form in the Unseen Place be that of a god. And to my brothers in wisdom who follow the Sacred Path, may your way be made smooth and the yoke be lifted from your neck. May you dwell forever in the Celestial Mansions.’

The person to whom the letter is addressed is clearly from a distinguished family. He is a scholar and scribe, ‘Keeper of the Royal Writings’, whose great-grandfather was ‘Overseer of the Great Pharaoh’ – an important administrative title during the Old and Middle Kingdom periods. His father was ‘Master of the Secret Ceremonies’ – that is, the head of Egypt’s ancient, hidden religion. He himself is ‘Captain of craft’ (we would call him ‘Admiral of the Fleet’) on voyages to ‘the Islands of the Outer Seas’. Greetings are also sent to the letter-writer’s ‘brothers in wisdom who follow the Sacred Path’. From the context of the Egyptian Books, this probably refers to the priests of the Old Religion whose secrets, inherited from an earlier civilisation, were kept well away from the eyes of ordinary Egyptian people.

The letter begins

‘In the month of rising watersviii, while all men yet bore the signs of lamentations for the departure of Pharaoh’s father and the great gates remained barred to wayfarers, the ships were prepared and pitched, and all was done as the king decreed. None but he who commanded our movements knew the preparations within the preparations.

‘Then, to the place of mooring I was carried in a high chair of ebony inlaid with brass, the bearers of which were of chesenam wood bound about with cowhide. On to the ship which had come laden with merchandise from the land of Pontas, lions tails, cowhides, spices, worked and unworked ivory, blackwood, oils and paint. From the land of Egypt went wrought copper and pitchers, stoneware, linen and the finery of women and men. There were instruments for dwelling places and corn in jars, beer and stones and the works of craftsmen.

‘I boarded and was greeted in a befitting manner, for my renown had gone before me. I am one who stands fast under assault, who does not waver at the crisis, nor run from the foe. Whose arm is cunning in battle and never strikes twice to slay.’

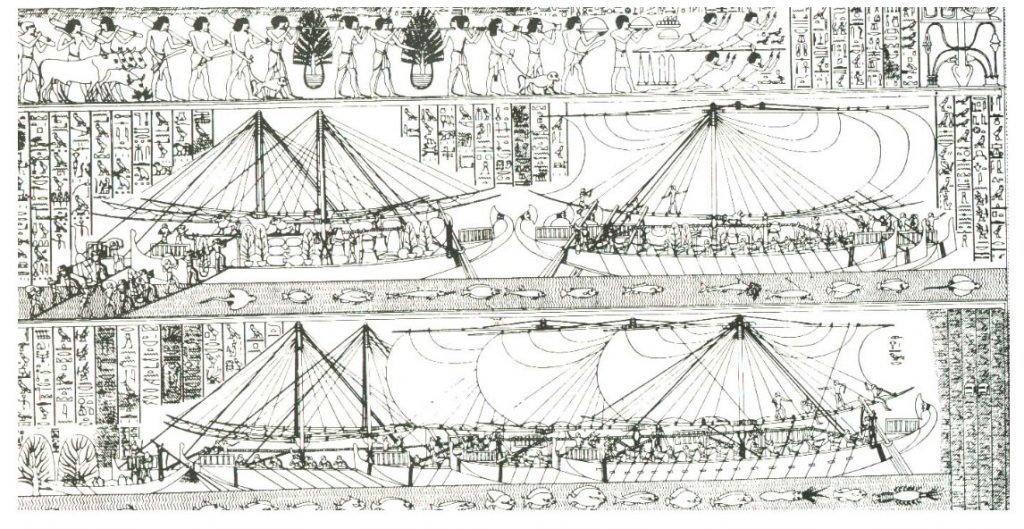

A name jumps out from these paragraphs: Pontas. This can only be the legendary Land of Puntix. The earliest ancient Egyptian voyages to Punt took place during the Fourth dynasty (early 25th century BC)x. More expeditions were made in the Fifth, Sixth, Eleventh and Twelfth dynastiesxi, but Punt’s glory days came during the 18th dynasty when the Pharaoh Hatshepsut (regent c.1479-73 BC, Pharaoh c. 1473-58 BC) built ships specifically to trade between the Gulf of Aqaba and Punt. Hatshepsut immortalised one expedition in reliefs on the walls of her Mortuary Temple at Deir el-Bahari near modern-day Luxorxii, which described ‘the loading of the ships very heavily with marvels of the country of Punt; all goodly fragrant woods of God’s Land, heaps of myrrh-resin, with fresh myrrh trees, with ebony and pure ivory, with green gold of Emu, with cinnamon wood, Khesyt wood, with Ihmut-incense, sonter-incense, eye cosmetic, with apes, monkeys, dogs, and with skins of the southern panther. Never was brought the like of this for any king who has been since the beginning.’xiii

Ships used for the Pharaoh Hatshepsut’s expedition to Punt. Drawing from reliefs on the walls of her mortuary temple, Edouard Naville, 1844-1926

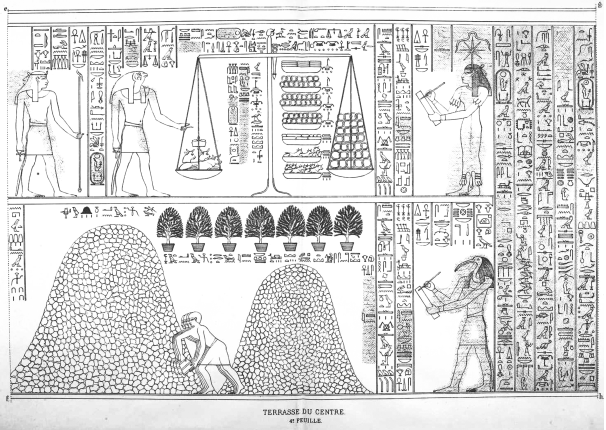

Measuring heaps of incense from Punt, drawings. Drawing from reliefs on the walls of the Pharaoh Hapshepsut’s mortuary temple, Auguste Mariette, 1821-81

The marvels of Punt. Drawing from reliefs on the walls of the Pharaoh Hapshepsut’s mortuary temple, Johannes Dümichen, 1833-94

Dating the letter

This begs the question: how early is the Kolbrin’s Early Egyptian Scroll? Historical events in the Kolbrin’s Egyptian books record nothing beyond the end of the 18th Dynasty. There might be a clue in the line ‘while all men yet bore the signs of lamentations for the departure of Pharaoh’s father and the great gates remained barred to wayfarers.’ The Ancient Egyptians used the term ‘God’s father’ not only as a title for Old Kingdom High Priests but also to signify a non-royal father of the king.xiv Of the few kings’ fathers referred to as ‘God’s father’ on inscriptions, Senwosret, probable father of the 12th-dynasty pharaoh Amenemhat I (c. 1981–52 BC) xv, comes closest to this Kolbrin record. He lived at the end of what is known as the ‘Second Intermediate Period’ – a period of national upheaval. The Kolbrin’s book of Manuscripts records two catastrophic visits by ‘the Destroyer’xvi which might have caused these two catastrophic periods and chaos for many years afterwardsxvii. Later in the Early Egyptian Scroll, a terrible storm is described with unusual movements in the heavens, signifying a time of climatic upheaval.

The Story of Sinuhe and The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor

A 12th-century BC Egyptian literary narrative entitled The Story of Sinuhexviii begins in a remarkably similar way to the Kolbrin letter: ‘The capital was silent, desires were weak, the Great Double Gate was locked / the court… and the nobles were mourning’.

In another 12th-dynasty narrative, The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor, the narrator describes a storm in which a star falls and an 18-foot tidal wave leads to the sailor of the title being shipwrecked, followed by a meeting with the Prince of Punt. As in the Kolbrin, the narrative even gives the dimensions of the sailor’s vessel.

Could these two fictional stories be based on a factual source – such as the account given in the Kolbrin? The events recorded – loss of a convoy of mighty ships with their precious cargo and men – would surely have been known and talked about for a long time afterwards in Egypt.

Exports to Punt

The letter sets out what the greatest ship has brought back form Punt, and this list includes some of the more practical commodities shown on Pharaoh Hatshepsut’s temple walls: ‘lions tails, cowhides, spices, worked and unworked ivory, blackwood, oils and paint’. ‘Paint’ would have been antimony, used for making kohl eye-paint. But the Kolbrin goes on to list Egypt’s exports to Punt: ‘wrought copper and pitchers, stoneware, linen and the finery of women and men… instruments for dwelling places and corn in jars, beer and stones and the works of craftsmen.’ Ancient Egyptian linen was renowned for its fine texture.xix ‘Instruments for dwelling places’ could have been household hardware. ‘Stones’ might have been gemstones, since they are mentioned immediately before ‘the works of craftsmen’.

A hidden agenda

Something mysterious emerges from the letter: although this appears to be a straightforward trading mission, there is a hidden agenda, and none but the king himself knows ‘the preparations within the preparations’. What is going on here? More on this later.

The captain is clearly a man of many parts – and certainly knows it!

The ships

The Kolbrin letter continues:

‘With the craft were men of the Kadanas, a host of men fierce of countenance and bold. The vessel was one hundred and fifty cubits less ten overall and in beam fifty cubits. With us there were one hundred and fifty men of the sea. The other craft with us was one hundred cubits overall and in beam thirty cubits, and had ninety men of the sea.’

The letter sets out the dimensions of the two biggest ships in the fleet, adding that the ships were pitched/covered in bitumen and the main ship manned by a fierce foreign crew. If the Biblical cubit of 18 inches is used for conversion purposes, the two vessels mentioned measured:

Main ship – 210 x 75 feet, manned by 150 sailors.

Second ship – 150 x 45 feet, manned by 90 sailors.

These two Egyptian ships are far bigger than any currently known and would have been formidable vessels.

Just how sea-worthy were they? According to the Egyptologist R. O. Faulkner, writing about the ships depicted at Deir el-Bahari, ‘the deep keel of the modern sailing yacht apart, the body-lines of the ships which sailed to Pwēnet in Queen Hatshepsut’s reign will bear comparison with those of a racing cutter of the present day.’xx In the past few decades, cutters or fast sailing ships have been used in the Clipper Race, a 40,000 nautical mile race around the world on a 70-foot ocean racing yacht.xxi

Who were the fierce ‘Kadanas’? These could have been African tribesmen who knew the seas around the Horn of Africa well. Or perhaps ’Kadanas’ is a skewed version of ‘Adanas’ and they were men of Adana – Hittitesxxii.

Where was Punt?

The website A catalogue of Ancient Coastal Settlements, Ports and Harboursxxiii gives many alternative names for Punt – Pount, Ta Netjer, Taneter, Pwenet, Pwene, Pouen, Opone – and places it ‘somewhere in East Africa, possibly in the area of the Afar people, between Adulis and Djibouti, on the location of the ancient D’mt (Da’amat) kingdom and close to the Kush kingdom and its gold mines, where they [traders] could also find silver, ivory, apes, and peacocks. Other possible locations for Punt are Adulis, Mundus-Mosylium and Opone.’ Most historians now agree that Punt was located in what is now the State of Somalia.

The voyage to Punt

The Book of Manuscripts goes on: ‘Past Kabas we sailed to Akar of the two ports, to await the tidings of Shumar.’

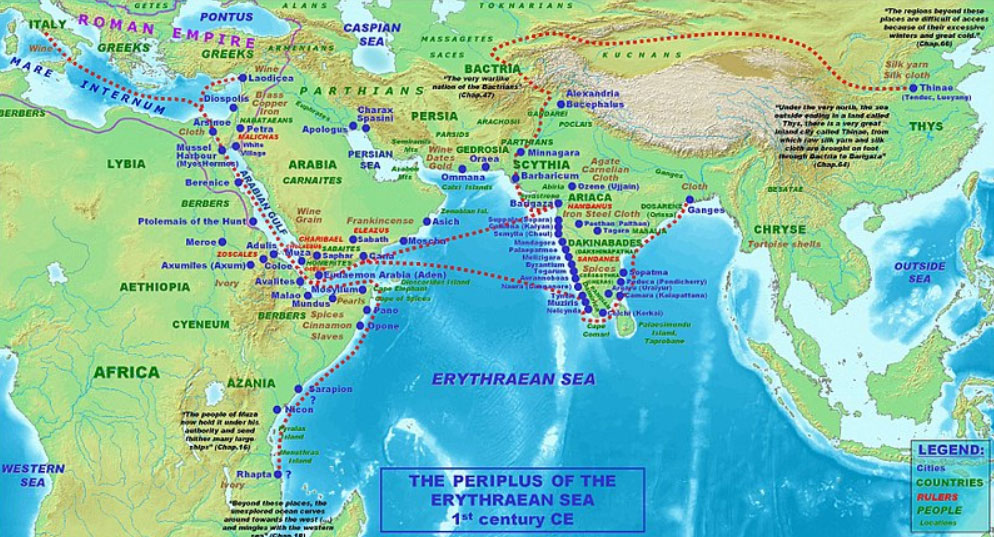

Frustratingly, the names Kabas, Akar-of-the-two-ports and Shumar cannot be firmly identified, even using detailed gazetteers of the Red Sea and Horn of Africa. Kabas might be ancient Gabaza, the port of Adulis, whose ruins lie within the modern Eritrean city of Zula. If Kabas were located further north, then Akarxxiv might have been a version of the name Aksum, the ancient inland city (and thus ‘waterless’) which later became a great Ethiopian empire; according to the mid-1st century AD Periplus of the Erithrean Sea, an ancient ruler of Aksum called Zoscales is known to have held sway over two harbours on the Red Sea – Adulis and Avalites. The Sudanese port of Aqiq echoes the name Akar. Many historians think that Punt encompassed both the African and Arabian coasts, which opens up the possibility of Ocelis/Akila near the Gulf of Aden.

‘The tidings of Shumar’ clearly refers to a person. It could be based on the ancient Arabic word shumar meaning ‘number, computation, an equal number’xxv. Could this have been a reckoner/accountant, or someone who would brief them on weather and sea conditions?

Disaster at sea

The text continues: ‘The waterless city [Akar] we left behind under the restless stars and we came up to Nasen, where we stood at our posts three days.’

Where or what was ‘Nasen’? The Latin word nasus meaning ‘spout, nozzle… a horn-like snout’ derives from Sanskrit ‘nas-‘, and at a stretch might be an ancient name for the Horn of Africa. But there is another possibility: since the stars above the ships were ‘restless’ (a sinister prospect for ancient sailors, who sailed by the stars) and in view of what was to follow, ‘Nasen’ could be a skewed version of the Ancient Egyptian word neshen / neshnn meaning ‘terror, fury, storm, calamity, disaster’xxvi:

‘The seas mounted up on high, the waters rose in wrath. Northwards we went and all but one vessel was lost, all but one boat sunk. I subdued the raging waters with cunning and the clouds were cleft by my skill. After many days were past, we came to the land in peace, we were not cast upon the shore. No man came near us when we hammered our postsxxvii. We set up altars and none denied us our rights. The God of that place made our God welcome.’

The southward-bound fleet was driven northwards and only one ship survived – probably the biggest vessel. We are not told where this ship eventually reached land, but ‘We came to the land in peace’ suggests that it washed up on an unfamiliar coast where the narrator and his crew were able to go ashore and give thanks for their deliverance without being attacked.

In Chad and Cameroon

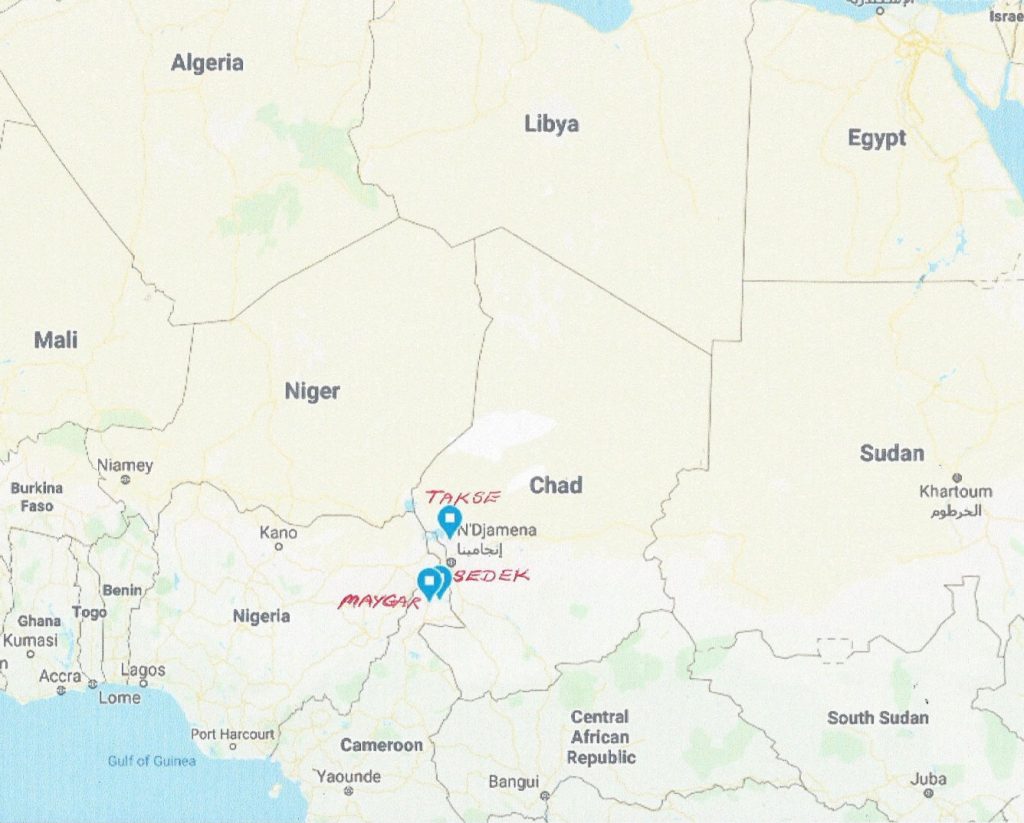

‘Then I went by way of the land of Sedek, which lies beyond Takse, to the lord Torka, an Egyptian, the second born greatest of twins, who ruled the people of Mayga. Here there are high mountains and great trees, and the roar of lions is heard in the night.’

Where are Takse, Sedek and Mayga? Fortunately, these ancient names have survived down the centuries almost intact. Takse/Tokse lies in southern Chad, south-east of Lake Chad and north of the modern city of N’Djamena. Sedek/Tsedek/Tsedok can be found in north Cameroon, south-west of Lake Maga. Note the name ‘Maga’. It indicates the narrator’s final destination – Mayga/Maga/Maroua, now the main town of north Cameroon, but according to the Kolbrin, once an entire region of mountains and forests with an Egyptian ruler. The Republic of Cameroon is known as ‘Little Africa’ because it has all the geographical areas of Africa and its products concentrated in a single area.

The Ancient Egyptians are known to have used an overland trans-Saharan route for trading with southern landsxxviii. The 5th-century BC Greek historian Herodotus mentions a camel caravan route going from Thebes down to Nigerxxix. Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE) noted that caravans of camels were managed by the Garamantes who lived south of Libya and acted as middlemen between the peoples of North Africa and sub-Saharan Africaxxx.

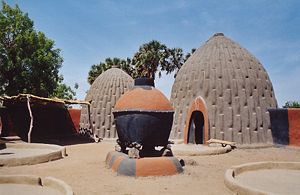

What evidence is there that the region now known as Cameroon region had connections with Ancient Egypt? Intriguingly, similarities have been noted between the culture of the present-day Bamileke tribe of West Cameroon and that of ancient Egypt – in their roof designs, carving and language. These have been recorded by Tchoutouo Tako Evanel Axel and Professor Robert Belcher of Georgia State University, USA – see Youtube video below.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vOdbi3fMXfI

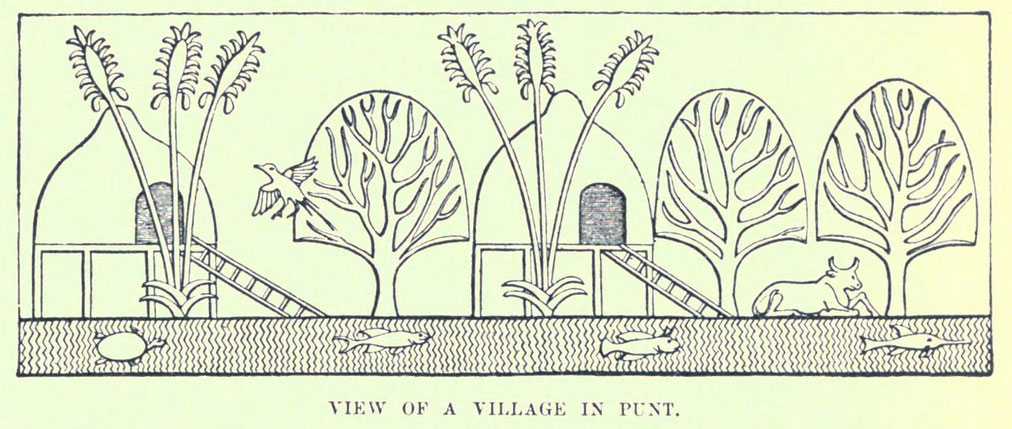

Traditional beehive-shaped mud huts in Cameroon (also found in Ethiopia and Somalia) echo the paintings of Punt huts shown on the walls of Hatshepsut’s temple at Deir el-Bahari.

Beehive huts built by the Musgum/Moosgoum people of the Maga region in the Far North Province of Cameroon

‘Maison obus’ by J. et M.F. Ostorero 2003 CCBYSA3.0

Was it just coincidence that the people of Mayga were ruled by an Egyptian? Or could Punt, the ‘Land of the God’xxxi with its many marvels, have stretched far more widely across Africa than is currently believed?

Distant Ophir…

Now comes the most surprising part of the letter:

‘The same lord Torka is he whose father, now in port, took his vessel south of Pontas from Ofir towards the sunsetting, past Kindia to the land of Bemer. He returned when the waters had risen four times and fallen thricexxxii, and sorrow gave way to rejoicing. To the rim of the great circle he went, to where the fires of the Netherworld were revealed and men were the brothers of dwarfs. He it was who brought back the great hairy giant who rests with Thosis.’

From the context, it sounds as though the person writing this letter may never have travelled beyond Punt, for he begins by saying that the voyage he is about to describe went even further, ‘south of Pontas’. He writes that Lord Torka’s father took his vessel ‘from Ofir towards the sunsetting’. This indicates that Lord Torka’s father was on a mission – presumably a trade mission – and was returning westward to Egypt from Ophir. Since the recipient of the letter is a ‘Captain of craft in the journey to the Islands of the Outer Seas’, he would have known the route.

Where were those Islands of the Outer Seas? They almost certainly correspond to the ‘sea outside’ mentioned in the Periplus of the Erythrean Sea (written c.40-70 AD) – that is, outside the limits of the Red Sea, Arabian Sea, Horn of Africa and even the Indian Ocean. According to the Periplus, the Outer Seas bordered ‘Thin’ or Chinaxxxiii.

Periplus of the Erythrean Sea showing ‘Outside Sea’ on the extreme right.

‘Map of the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea’ by PHGCOM, CCBYSA4.0

Ancient Indian writers alluded to the Islands of the Outer Seas as Suvarnabhumi (‘the Land of Gold’) or Suvarnadvipa (‘the Island of Gold’). ‘Sometimes this is interpreted to mean only certain of the 17,000 islands of Indonesia, sometimes it means the island of Sumatra. Arab writers such as Al Biruni wrote that Indians called the whole South-east region Suwarndib (Suvarnadvipa). Hellenistic geographers knew the area as the Golden Ghersonese. The Chinese called it Kin-Lin. ‘Kin’ in Chinese means gold.’xxxiv

According to the 16th-century writer Tomé Pires, a diplomat and apothecary from Lisbon who spent several years in Malacca collecting information on the Malay–Indonesian region, Ophir was ‘delante de China hacia el mar, las islas donde muchos de los moluqueños, chino, y se reunió con el comercio Lequios (in front of China towards the sea, of many islands where the Moluccans, Chinese, and Lequios met to trade)’xxxv.

Anna T.N. Bennett writes in her article ‘Gold in early Southeast Asia / L’or dans le Sud-Est asiatique ancien’ that Suvarnabhumi/the Land of Gold ‘is thought to refer to the mainland, including lower Burma and the Thai Malay Peninsula’ and that Suvarnadvipa/Islands of Gold may correspond to the Indonesian Archipelago, including Sumatra’.xxxvi Ancient shafts have been reported in Central Vietnam, Classical gold coins found in southwest Sumatra and Iron Age bronzes discovered in a mine shaft in Laos; but although evidence of ancient gold-prospecting has been found across Southeast Asia, Bennett points out that ‘most of the gold in the prehistoric and early historic periods would… have been extracted by panning alluvial sediments, a technique requiring little capital investment in equipment and no specialist technology, but unfortunately leaving no discernable archaeological signature.’xxxvii

Would the prospect of gold have lured the Ancient Egyptians to the same region as King Solomon’s ships?xxxviii ‘Kindia’ literally means ‘the Land of Gold’- but the letter says that Lord Torka’s father’s ship sailed ‘past Kindia to the land of Bemer’. This suggests that Kindia was already known to the Egyptians. The name is mentioned elsewhere in the Kolbrin as being in ‘the Eastern Quarter’ where one of the four sets of Sacred Records was kept. Getting there involved sailing ‘around the edge of the Earth’xxxix ‘Bemer’ is Bmer/Bamar/Burma (modern Myanmar); the Bamar people originally lived on the borders of China and Tibet, arriving in north Burma in the 9th century ADxl.

The fires of the Netherworld

There can be no doubt about the location of the ‘rim of the great circle’, ‘where the fires of the Netherworld were revealed’. This is the Ring of Fire, a ‘the linear zone of seismic and volcanic activity that coincides in general with the margins of the Pacific Plate.’xli

The Pacific Ring of Fire

USGS – http://pubs.usgs.gov/publications/text/fire.html, Public Domain

Indonesian section of the Pacific Ring of Fire showing active volcanoes

Lyn Topinka, USGS; base map from CIA, 1997; volcanoes from Simkin and Siebert, 1994. Public Domain

The text suggests that the seismic history of the Ring of Fire was known to the Ancient Egyptians. The narrator adds that it was a place where ‘men were the brothers of dwarfs’. This corresponds with a string of islands in the Ring of Fire known as the Nusa Tenggara: Timor, Alor, Flores, Komodo, Sumba, Sumbawa, Lombok and Bali. Recent archaeological discoveries of the bones of Homo Floresiensisxlii on the Indonesian island of Flores and of Homo luzonensis in the Philippinesxliii confirm that races of pygmy humans once inhabited south-east Asia. Scientists believe the pygmy races existed between 100,000 and 50,000 years ago, but this letter reveals there were still pygmy people in Indonesia when Lord Torka’s father sailed there.

Reconstruction of a Homo floresiensis woman, Hall of Human Origins, Smithsonian Natural History Museum, Ryan Somma [CCBYSA2.0]

The Outer Islands would have seemed as exotic as Punt to the Egyptians, with their incense and spices, their towering rainforests, active volcanoes and lakes in ever-changing colours on the island of Flores, and man-eating lizards on Komodo and Rinca.

Commodities such as styrax benzoin and electrum may well have been brought back to Egypt from Southeast Asia. Dhani Irwanto’s book Land of Punt: in search of the divine land of the Egyptians, makes an exhaustive breakdown of the imports painted on the Deir el-Bahari reliefs and suggests where they might have come from. Irwanto is convinced that the island of Sumatera/Sumatra was the Land of Punt. The Kolbrin suggests otherwise – but its references to expeditions to the Outer Islands/Ophir open up the distinct possibility that the Egyptians travelled to many far-flung places for their goods.

The narrator adds that a ‘great hairy giant’ was brought back from this region, who now rests ‘with Thosis’xliv.

The letter draws to a close

‘Now my lord [Torka] is one hundred and ten years of age. I, alone among his men, understand the hidden words of the gods and the secret ways. I alone know the writing within the writing. I alone know the nature of the Lords of the Celestial Mansions. Therefore, the words of God come to you by the hand of the servant of The Great God, the Guardian of the Book. Thus you may know all that has been made known to those who have slept in the House of the Gods.

‘Keep the writings as they now are for your children and your children’s children. Nothing is perfect on an imperfect Earth, but that which flows down and reaches us from the heart of God comes the nearest to perfection. The pure waters are sullied only by the imperfect and impure vessel in which they are caught.

‘As it is written, so let it be re-written. As it is written, so let it be done.’

This part of the letter is enigmatic, raising many unanswerable questions:

Was 110 years an unusual age at that time? Or does it suggest that some human beings still lived to a much greater age during the period when this letter was written?xlv

‘The writing within the writing’ confirms what is already known – that Egyptian sacred texts contained several meanings.

Who were ‘the Lords of the Celestial mansions’? And what were the ‘Celestial mansions’? The word ‘celestial’ indicates a link to the heavens.

Who was the ‘Guardian of the Book’? The Kolbrin contains other references to The Guardian of the Book. Four guardians were selected to safeguard each of the four sets of the Great Book of the Egyptians and The Lesser Book of The Egyptians. Each set consisted of one hundred and thirty-two scrolls and five ring-bound volumes. These comprised the Book of the Trial of the Great God, the Sacred Register, the Book of Establishment, the Book of Magical Concoctions, the Book of Songs, the Book of Creation, the Book of Destruction, the Book of Tribulation and the Great Book of the Sons of Fire which contained, among other texts, The Book of Secret Lore and The Book of Decrees. The Kolbrin’s six Egyptian Books are all that now remain of the copy of the Great Book brought back from Kindia in the Eastern Quarterxlvi.

As to what happened to the three other copies of the Great Book secreted in the other Quarters of the Earthxlvii – who knows? But Lord Torka’s father’s voyage to South-east Asia might well have had little to do with trade and everything to do with secreting or retrieving a copy of the Great Book of the Egyptians in the Eastern Quarter.

Lastly, what is meant by the enigmatic statement, ‘Thus you may know all that has been made known to those who have slept in the House of the Gods.’? Does this refer to those individuals who underwent the Hibsathy ritual, involving lengthy preparation, dangerous narcotics and terrible ordeals leading to a near-death experience? Or does it carry a simpler meaning?xlviii

For all its opaque references, the Early Egyptian Scroll is remarkable. It states loud and clear that at some time during their lengthy civilisation the Ancient Egyptians built great ships which took them south to Punt, sometimes in the face of catastrophic storms; that they journeyed overland into the heart of Africa; that they sailed to and traded with Ophir – which could have included gold-yielding regions such as Borneo, the Philippines, Burma, the Malay Peninsulaxlix, Sumatra and the Indonesian archipelago. And one stout-hearted Egyptian even sailed to a place so strange that he brought back a giant as a souvenir.

The author welcomes correspondence with readers via [email protected].

Kolbrin text courtesy of The Culdian Trust.

References

i‘The Shipwrecked Sailor’, The Literature of Ancient Egypt, ed. William Kelly Simpson (Yale University Press, 2003)

ivhttps://www.ancient-code.com/translated-this-is-what-the-5000-year-old-ancient-egyptian-hieroglyphs-in-australia-say/

vii‘Quinquireme of Nineveh from distant Ophir

Rowing home to haven in sunny Palestine,

With a cargo of ivory,

And apes and peacocks,

Sandalwood, cedarwood, and sweet white wine.’

From Salt-Water Ballads, (Grant Richards, 1902)

The Kolbrin refers elsewhere to Pontas: Manuscripts 31 reads:’ It is said that Kelathi lay within the borders of Kahemu [Egypt], but could it not have been the land of similar sounding name outward from Pontas beyond Godsland?… Now we know that the life tree grew in Taleus, which is towards the Lands of Dawn, by Pontas.’

Ancient Records of Egypt, Volume 1, The First through the Seventeenth Dynasties, James Henry Breasted.

Ibid.

Ancient Records of Egypt, Volume 2, The Eighteenth Dynasty, James Henry Breasted.

Ibid.

The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, Aidan Dodson and Dyan Hilton (Thames & Hudson, 2004)

Ibid.

For more on the Destroyer, see https://grahamhancock.com/whitemany1/, https://grahamhancock.com/whitemany2/https://grahamhancock.com/whitemany6/, https://grahamhancock.com/whitemany11/

The Kolbrin, Book of Manuscripts 33:5. (Note that the Kolbrin scribe gives Egypt’s age as 120 generations since Osiris, which multiplied by 70 years per generation comes to 8,400 years – 5,000 years longer than currently estimated.)

‘The Story of Sinuhe’, The Literature of Ancient Egypt, ed. William Kelly Simpson (Yale University Press, 2003)

‘Egyptian Seagoing Ships’, R. O. Faulkner, The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 26 (Feb., 1941), pp. 3-9.

Akar/Acre was a much-used Ancient Egyptian harbour on the modern-day Israeli coast – but it had only a single port, not two, and it was located in the Mediterranean Sea, not south of the Red Sea where an expedition to Punt would have sailed.

Dictionary, Persian, Arabic, and English: with a dissertation on the languages, literature, and manners of Eastern nations, John Richardson, Sir Charles Wilkins, 1806

Herodotus, Histories, Bk 4. 181-5

Pliny the Elder, Natural History 5.35-8

Ta netjer (tꜣ nṯr), the ‘Land of the God’– John Henry Breasted (1906–1907), Ancient Records of Egypt: Historical Documents from the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest, collected, edited, and translated, with Commentary, p.433, vol.1

Ancient Egyptians measured years according to the annual flooding of the River Nile, so this means four-and-half-years. By comparison, King Solomon’s voyages to Ophir took three-and-a-half years.

Tomé Pires, Compañía General de Tabacos de Filipinas. Colección general de documentos relativos a las Islas Filipinas existentes en el Archivo de Indias de Sevilla. Tomo III–Documento 98, 1520-1528. pp. 112–138. Also http://rca.open.ed.jp/web_e/history/story/epoch2/daikoeki_5.html.

https://journals.openedition.org/archeosciences/2072 – Distribution of gold ores in South-East Asia

Ibid.

https://www.kingjamesbibleonline.org/Ophir/

https://www.bible-history.com/archaeology/israel/2-gold-of-ophir-bb.html

Book of the Sons of Fire 13: ‘We know about Lothan and Kabel Kai, designer of houses, who sailed around the edge of the Earth. With them was Raileb, the scribe, who knew hidden mysteries. They gathered the records, which were in Kindia, and carried them the long sea journey.’

Book of Manuscripts 28: ‘We journey into Kindia, where there are pines.’

‘with Thoth?’ Since Thoth was god of the dead, this is probably a way of saying that the giant hominid is now dead.

For more information on the human lifespan shortening, see my article https://grahamhancock.com/whitemany7/ under subheading ‘The human lifespan shortens’,

‘Beneath the altar is the Grave of Life, kept dry with mortar. In its place is the Great Chest of Mysteries and in the Urns of Life are the records. Well kept they are and safe from the unlearned, all the records of the Eastern Quarter…

‘We go by way of Kambusis and the waters of Jabel, over the wild wilderness to the Mountains of Winds. Beyond them we journey into Kindia, where there are pines. We shall take the records of the Eastern Quarter and the Guardians who remain with us. None among all who know our ways shall be forced to go, neither shall we condemn those who remain. The scrolls in four chests

and the Books of Wisdom in their canopies go with those who depart.’ (Kolbrin, Book of the Sons of Fire).

Sumerian and Akkadian texts sometimes refer to the ‘four quarters of the world’ or ‘four corners of the world’; the Ancient Egyptians adopted this usage.

For more information on the Hibsathy, see my article https://grahamhancock.com/whitemany9/.

The Malay Peninsula: its mineral wealth, with a citation of authorities for identifying it with the Ophir of Jewish History and the Golden Chersonese of classical writers, C.B. Dowden, London, 1882 (British Library, Historical Print Editions).

Fascinating and thought provoking. Enjoyable article. Thank you.

Love this! Another fascinating window on a lost world.