The Goddess of Venus Transformed

As described in my previous article (https://grahamhancock.com/eilinga11/), the impact of the minor planet Dumuzi transformed the planet Venus into a radiation monster that triggered a climate catastrophe on Earth. The Earth’s atmosphere reached roaring hot temperatures, and vaporized water enveloped the Earth in a thick cloud mantle. From these clouds, it rained down in torrential gushes, streams became rivers and huge lakes covered low-lying areas. Planet Earth drowned in a deluge.

The flood was so dramatic that the Mesoamerican peoples began their calendar with this flash from Venus. For us, the assignment of this catastrophic event to the beginning of the Mayan calendar has a secondary effect in that we can pinpoint the event to 3114 BC.1

When the cloud cover enveloped the entire Earth, the heat wave slackened, and people looked up to the sky again; a newly born dragon stood in the sky instead of the familiar Venus. The solar wind hit a gigantically bloated atmosphere and gradually stripped its upper layers.

The myths capture Venus’ various appearances, where, besides the initial flash from Venus, a comet-like tail, huge enough to extend to the Earth’s orbit, emanated in the aftermath. The hymn (NIN-ME- SÁR-RA) to Inanna reports on how the Earth was surrounded by a glowing tail: 2

A flood descending from its mountain,

Oh foremost one, you are the Inanna of heaven and earth!

Raining the fanned fire down upon the nation,

…

When mankind comes before you

in fear and trembling at (your) tempestuous radiance,

…

After the impact of Dumuzi, Venus transformed into a glowing disk from which a tail many millions of kilometers long emanated, blazing and billowing. The planet had taken on the appearance of a comet, only infinitely much larger.

This tail of Venus and its appearance have been passed down through myths in many forms. In support of my view, physics and the descriptions of the tail in ancient reports fit together perfectly.

The destructive power generated by the ‘flaming’ Venus, i.e. Inanna, is kept, for example, in the ‘Hymnal Prayer of Enheduannna’: 3

Vegetation ceases, when You thunder like Ishkur,4

You who bring down the Flood from the mountain,

Supreme One, who are the Inanna of Heaven (and) Earth,

Who rain flaming fire over the land,

Who have been given the me by An,

Queen Who Rides the Beasts,

at the holy command of An, utters the (divine) words,

Who can fathom Your great rites!

In view of this rather allegorical description of a celestial object transforming into a beauty with a tail, it is almost trivial that worldwide myths have described Venus as the smoking star, using for description the same wording that is used to describe comets.

Depictions of the New Venus

From a physical point of view, reliefs are perhaps the most convincing proof of the correctness of my interpretation.

Figure A

Structures on a relief that are officially interpreted as posts or reed bundles.

Left: Relief on the Warka vase (ca. 3500-3000 BC) found in archaic layer III of the temple precinct of the goddess Inanna in Uruk 5 (CCBYSA4.0) by Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin

Right: Detail from a calcite cylinder seal (BM ME 116722) (ca. 3300-3000 BC) with the so-called ‘bundle of reeds’ of Inanna. 6 (CCBYSA4.0) by Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin

As pictogram, the name of Inanna was written using these posts as sign, which enables us to further classify these mysterious “double posts”.7 Trivially, this pictogram meaning ‘Inanna’ was most commonly found in the Inanna district of ancient Uruk (specifically the Uruk IV period dating from 4000 to 3000 BC) I am convinced that the structure officially called a post is actually a cosmic tail fed by the bloated atmosphere of Venus. Thus, instead of a meaningless description, my interpretation explains what served as a template for this Inanna pictogram.

A closer look at a comet’s structure backs up our explanation. The two bundles at the tip are archetypal structures of a comet and its tail. The solar wind splits the tail into two, a plasma and a dust tail (see Figure B). This is precisely the double structure that the reliefs emphasize.

Figure B

Tail of the comet Hale Boop (March 1997) 8

Note the double structure consists of a plasma tail (blue) and a dust tail (whitish)

(Public Domain)

Ev Cochrane summarizes his literature research on the historical description of Venus’ appearance as follows: 9

A survey of the lexicons of various ancient cultures reveals that the terminology attached to the comets finds a striking correspondence with that employed to describe the planet Venus.

…. From ancient literature which likewise describes the planet Venus with comet like characteristics (disheveled hair, serpentine form, tailed body, bearded, agent of eclipses, etc.)

The ancient characterization seems rather unsuitable for the goddess of love. But, in my interpretation, the ambivalent features are perfectly fitting.

In a diligent analysis of ancient hymns and texts, Morris Jastrow convincingly demonstrates that the description of Venus as ‘bearded’ is not a description of a trans or bisexual being. The term “bearded” was used to describe the characteristics of the planet and not a bearded hermaphrodite. In particular, I like his logically derived assessment of how myths can be understood as ancient messages: 10

The question may however be raised; whether the “reality” does not come first and the « metaphor » afterwards? In other words, is it not because the goddess Ishtar was also pictured as a male deity, embellished with a beard, that the thought arose after her identification with the planet Venus, of describing her brilliancy by means of the phrase in question? To most of us such a manner of reasoning seems like turning thing topsyturvy. One can understand that a misunderstood, or a no longer understood metaphor, should be taken as a reality, but hardly the reverse.

Be that as it may, the pillar-like reliefs depicting Inanna were continued in a more abstract form by becoming the starting point for a proto-cuneiform sign meaning Inanna.

Similar to Egypt, where the wheel of fire of the Red Sun first became the symbol for the god Ra and then, reflecting his name, the letter with the phonetic value ‘r’10b. Analogously, in Sumer, the symbol used to capture the goddess Inanna, in her appearance as a comet, became a letter and perhaps even triggered the development of cuneiform writing.

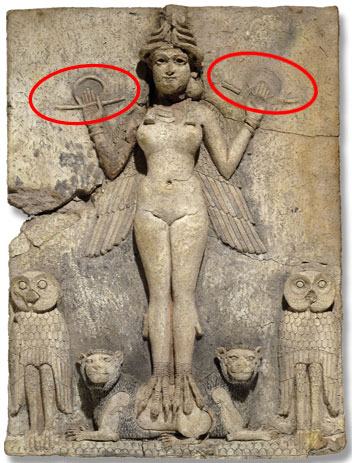

Figure C

Variations of a proto-wedge cuneiform character used to write the name Inanna.

The expanding dust tail and the longer bundled plasma tail are likely the background of the glyph, which aptly depicts a comet.

(CCBYSA4.0) by Zunkir

Another pictorial representation of the comet-like Venus, which became a symbol of the goddess, is given an even more detailed depiction in the so-called Inanna knot.

Figure D: Relief of an Inanna knot, which is described and officially understood as a bundle of reeds.

(Photo Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin, CCBYSA4.0)

The opinion that the Inanna knot represents a bundle of reeds can only be developed by a trained archaeologist with a sufficiently firm belief. To truly categorize this ancient symbol, modern comet research (Figure E) allows us to classify it as an image representing the structure of a comet’s tail.

Figure E Ejection of dust particles from the surface of a comet nucleus (Comet_Hyakutake) 11

A “difference image” is shown here to highlight the structure. (CCBY4.0), by ESO.

In our model of a water-loaded minor planet that orbited the sun before it collided with Venus, we find all the mysterious descriptions and depictions of myths and reliefs consistently explained. Just as the double columns, shown in Figure A, represent the comet’s tail, the knot of Inanna is represented by the solar wind drawing away dust clouds ejected into the atmosphere. This dust load in the atmosphere emerged when vaporizing gases burst out of vacuoles and the gas released from lava-hot rock entrained dust. This dust and atmospheric gas formed a double tail swirling around the planet. Shapes of sufficient density formed, as shown in Figure D, just as we find in the structure of the knot of Inanna.

A planet which turns into a giant comet trails with a cloud dense enough to eclipse the Sun. Size and density are orders of magnitude greater than the thin veil of gas following a comparatively tiny comet.

Ev Cochrane points to depictions of Venus in pre-Columbian South America and in Siberia, in which Venus, as a central sphere, is surrounded by a ring of hooks.12

Not for the first time elucidating puzzles of this kind, my astronomical approach leads the way to a sound theory.

Myths and Reliefs

The description of a comet as a torch fits perfectly with its appearance. This pictorial analogy is repeatedly used in the various hymns to Inanna: 13

For the young lady I shall sing a song about her grandeur, about her greatness, about her exalted dignity; about her radiantly ascending at evening; about her filling the heaven like a holy torch; about her stance in the heavens, as noticeable by all lands, ….

Such an enlarged tail structure fits in with a Yakut legend that once again links Venus with terrible events: 14

It is said to be ‘the daughter of the Devil and to have had a tail in the early days. If it approaches the earth, it means destruction, storm and frost, even in the summer; …

Other ancient peoples knew variations of this Yakut legend. In the Norse sagas, it is the otherwise beautiful Huldra who sports as a physical feature a tail.15

The transformation caused by the impact was not the permanent state of Venus. In the long run, the planet returned to a state similar to that before the impact. Some changes, however, were irreversible, such as water being irrevocably blown into space and thus permanently lost. Initially, the changes were rapid, but even in its current state, Venus’s temperature will not reach a new balance between radiation and irradiation from the Sun until many more millennia have passed.

Successively, Venus ran through various intermediate phases. The short-term initial phase left the earthly observer with the impression of a super-bright celestial object. We find this appearance of an extremely bright Venus depicted on Mesopotamia reliefs.16

Just as physics can explain these appearances of Venus, it also solves the puzzle of what the representation of a ‘Venus sun’ with a crescent in front of it might be all about.

Figure F

Typical depiction of Venus on Mesopotamian reliefs

The eight-pointed star, the typical Venus symbol, is accompanied by a moon-like crescent in front of it.

This selected relief shows the enthronement of King Ibbi-Sin (2028 – 2004 BC) from the third dynasty of Ur under the sign of Venus, i.e. the goddess Inanna.17

(CC0), Metropolitan Museum of Art

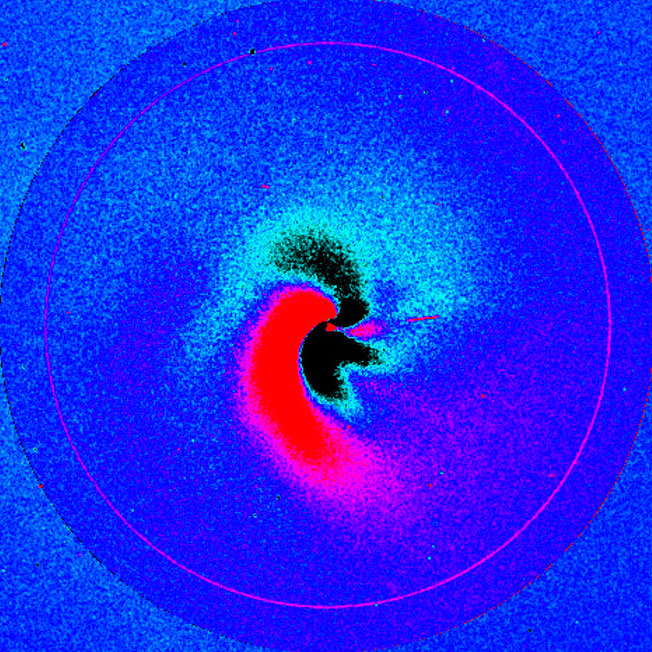

With regard to the development of Venus after the impact, the celestial spectacle that was ushered in so dramatically changes its drama when the solar wind strips off the upper layer of the inflated atmosphere.

Once the raging gas and dust clouds calmed down, a different but equally interesting situation developed. The atmosphere remained inflated, and the solar wind continued to push against this large obstacle in the way of its blow. A crescent-shaped bow shock wave built up in front of the solar wind. An elongated system of various regions developed. Illuminated by the Sun, each of these states differentiates by its optical appearance. The geometry of this next state is illustrated in Figure G.

Figure G

Left: Geometric model of the different regions resulting from the interaction of an inflated Venus’ atmosphere with the solar wind.18

Right: A lion’s head,19 as used as a naturalistic image to describe the disheveled Venusian atmosphere in the myths.

(CCBY2.0) by Ankit Gita

To contextualize the pictorial description with related physics, I refer to Christopher T. Russel and Oleg Vaisberg’s explanation of the interaction of the solar wind with today’s Venus’ atmosphere: 20

The obstacle is the planetary ionopause; … Behind the planet a tail is formed by flux tubes which become filled with plasma on the day side and convect around the planet ….

The compressed area at the bow shock wave will be the most conspicuous, forming an optical crescent. The solar wind tugs at the bloated atmosphere and tears gas out of the outer layers. The geometry of the various states in front of, around and behind the planet is shown in the sketch shown in Figure G.

Close to the planet, a shredded gas cloud shines particularly brightly. On cooling, it condenses into denser clouds, which become optically dark. The assignment of a lion’s head as a naturalistic picture of the fragmented zone behind the planet is apt.

The appearance of the crescent-shaped bow shock around the planet could have been the model for a widespread power symbol. Possibly, both Inanna’s lead rope of heaven and the Egyptian Shen sign 21 reflect the curved sickle-shaped luminous stream of gas.

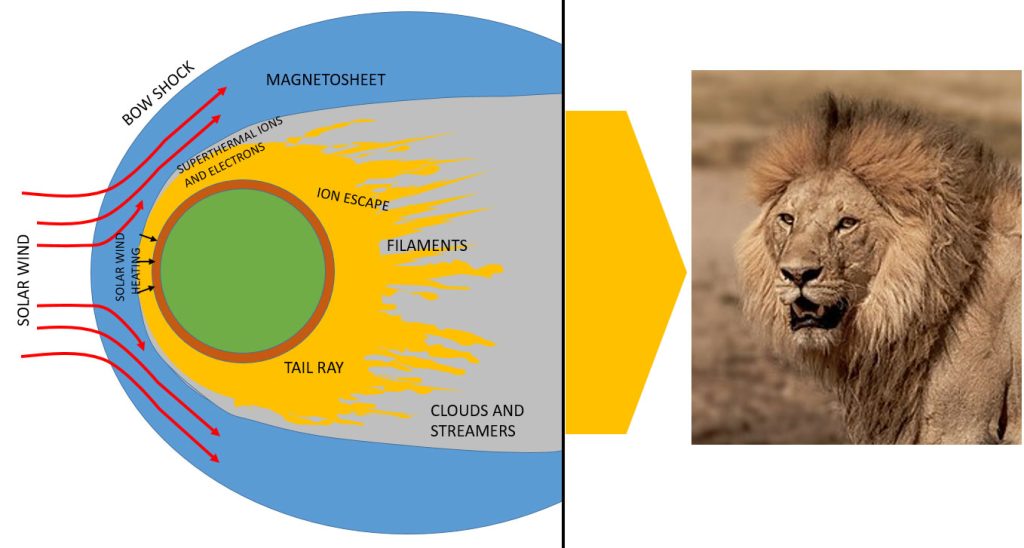

Figure H

Rectangular fired clay plaque

Modelled in relief on the front is depicted a nude female figure 22 officially classified to show the goddess Ishtar (Inanna in Sumerian).23

The ‘lead ropes’ she is holding are encircled. Note the feet depicted as paws, the wings to indicate her celestial provenance and the lions on which she stands.

(CCBYSA4.0) by Conricus

Venus had absorbed her husband, which made him glare up after having merged with her. This event generated the warlike aspect of the goddess, whose ferocity was, in addition, expressed by the wreath of fire that enveloped her after the marriage. As some female spiders do, the goddess ate her husband. All this combined, the goddess with the red-golden aura of terror was born.

Fitting to this understanding is also the Samoan legend Ev Cochrane cites: 24

…. it was said, that Venus was a primeval Fijian queen, who, upon going berserk, suddenly, sprouted horns from her head and engaged in cannibalistic practices.

Even in scattered quotations from Christian times, scanty remnants of a cosmic catastrophe caused by Venus have survived. The Sibylline Oracles, from which I quote here, represent a collection of pseudepigraphical poems venerable because of their antiquity. These Sibylline books from Christian times should not be confused with the divination books of the same name that were kept in ancient Rome. The fact is, these Christianized poems are based on messages from very ancient times. Here is a quote that refers to the Venus myth: 25

The threatening of the shining sun I saw

Among the stars, and in the lightning flash

The dire wrath of the moon. The stars travailed

With battle; God permitted them to fight.

For in the sun’s stead long fire-flames arose;

The morning star made fight and trod upon

The Lion’s back, and the moon’s double horn.

The Roman writer Marcus Terentius Varro also uses a feature of a lion to describe Venus: 26

…

this time is by the Greeks called ἑσπέρα, and vesper (evening in Latin); just as, because the same star before sunrise is called iubar (dawn-star), which means maned, …

In this text, the use of the word ‘mane’ fits the image of a Venus with the features of a lion. Varro’s text confirms my interpretation, especially as the Romans used the same word to describe a comet.

This naturalistic description was used for millennia. Already, in one of the earliest Sumerian myths, Inanna, i.e. Venus, is likened to a lion. A hymn to her says: 27

Inana, great light, lioness of heaven ….

In another hymn, Inanna is characterized as: 28

She stirs confusion and chaos against those who are disobedient to her, speeding carnage and inciting the devastating flood, clothed in terrifying radiance. It is her game to speed conflict and battle, untiring, strapping on her sandals. Clothed (?) in a furious storm, a whirlwind, …

The couple of Dumuzi and Inanna represent a dramaturgically interesting and common constellation: a love match turns into rejection. The lover is annihilated or, just as badly, banished to hell. The contradictory character of Inanna, being the goddess of love and as well of war, is merely an allegory of strange events in the canopy. My interpretation resolves the oddity of Inanna’s duality, which Ev Cochrane very rightly poses:

What is there about the planet Venus that could have inspired such grim rites? Venus’ present appearance would never inspire mass hysteria or vivid tales of impending doom and world destruction. How, then, are we to account for the fact that Sahagun’s testimony documenting the Aztec’s attitude towards Venus echoes the Sumerian skywatchers’ conception of Inanna/Venus: “To provoke shivers of fright, panic, trembling, and terror before the halo of your fearsome splendor, that is in your nature, oh Inanna!”

To underpin the duality, some lines in a hymn to this warlike and wild goddess of love go like this: 29

In the midst of battle when I take my place,

The heart of battle, the arm of heroic courage, the strength of heroism, am I.

Behind the battle when I approach,

A conquering power which hostilely attacks, am I.

…..

Through my appearance fear is established in the heavens

Through my radiance the fishes are affrighted in the deep.

The aspect of a bloodthirsty goddess also holds true for Inanna’s counterpart, the Indian goddess Kali. The description of Kali goes like this: 30

The dread Mother dances naked in the battlefield.

Her lolling tongue burns like a red flame of fire.

Her dark tresses fly in the sky, sweeping away the sun and stars.

Red streams of blood run from her cloud-black limbs.

And the world trembles and cracks under her tread.

This nature is dramatically reinforced in the image of the Aztec goddess Itzpapalotl. A drawing illustrated the attitude much clearer than any description. It shows a grotesquely exaggerated, woman-like creature with claws, protruding hair, a necklace made of hearts and chopped-off hands.

Figure I

Picture of the goddess Itzapaplotl as shown in the Codex Magliabecchiano 31

Public Domain

All these various myths describe a raging sky goddess hell-bent to destroy. This similarity in the description and function of these goddesses is all the more astonishing as there are more than 3000 years between the Aztec myths and the myth of the Sumerian Inanna. What looks like myths, once they have found their way into popular belief, may be changeable in names and details but eternal at their core.

Remarkable parallels to Inanna exist in the case of the Egyptian goddess Hathor. The war-like attitude, the devastations, the raging storm, and the fire-spewing serpent of the Eye of Horus that she commands indicate that in the myths about Hathor, the same event is captured, which triggered the myth about Inanna.

Egyptian myths are also more complex because of the connection between Hathor and the strange character of the Eye of Ra (sometimes called the Eye Horus), which acts independently from the gods. The devastation wreaked by Hathor—or alternatively by the raging Eye of the God—fits in with what the Mesopotamian myths report about Venus running amok.

When Cicero talks about the repeating global catastrophes in his treatise “Somnium Scipionis” (sixth book of ‘De re publica’), he restates what Plato had said 300 years earlier in his Timaeus. The following quote is less well-known and less dramatic than Plato’s account of the fall of Atlantis, but it is at least as revealing for my revision of human history: 32

And the reason of it is this: many and manifold are the destructions of mankind that have been and shall be; the greatest are by fire and by water; but besides these there are lesser ones in countless other fashions. For indeed that tale that is also told among you, how that Phaethon, the child of the Sun, yoked his father’s chariot, and for that he could not drive in his father’s path, he burnt up all things upon earth and himself was smitten by a thunderbolt and slain—this story, as it is told, has the fashion of a fable; but the truth of it is a deviation of the bodies that move round the earth in the heavens, whereby comes at long intervals of time a destruction with much fire of the things that are upon earth.

The accounts of Plato and Cicero are, so to speak, the best-known “official” news, but there are countless legends of this kind on all continents and among (almost) all peoples from prehistoric times, regardless of their level of cultural and civilizational development at the time.

A Scientific View

These widespread traditions exist for good reason. They are part of a deeply rooted human collective memory. The fact that there have been a number of global catastrophes in human history, with the Flood just being the most prominent, is common knowledge and yet is very often relegated to the realm of fable. This is an astonishing ignorance, as scientists who take a serious look at the subject are not only convinced, but are gathering more and more facts to support the multiple catastrophe theory.

In this case, I am referring to Gunnar Heinsohn, who argues that both kingship and bloody sacrificial cults, whether animal or human sacrifice, are linked to a global catastrophe. This catastrophe was of cosmic origin, and Venus played a central role. I think he asks the right question when he says: 33

At Uruk, for example, the earliest “Inanna symbols in the form of animal figurines” were dug up in the Enanna complex directly above a destruction layer and indicate how intensely the survivors concerned themselves with her. I propose now to give a survey of archaeologically tangible Bronze Age catastrophes (see Table 1) and then to address the question how mankind was able to cope with the cataclysms, or why they produced sacrificial cults, temples, and priests.

After the Bronze Age, catastrophes of a global extent cannot be shown convincingly to have occurred.

| Archaeologically attested evidence of Catastrophes in Bronze Age Mesopotamia |

| The Myth of the dying Redeemer God, the Virgin Birth and the Madonna with Child |

| Last destruction layer with collapse of the Babylonian Ziggurat tower of Kish |

| Bronze Age/Early Dynastic IIIb and Old Akkadians with Iron knives (Chagar Bazar, Tell Asmar) |

| Flood or destruction layer found in Ur and Kish, sterile deposit below lime stone temple in Uruk |

| Bronze Age/Early Dynastic II/IIIa with start of archaic cuneiform writing |

| Flood or destruction layer found in Ur and Kish |

| Bronze Age/Early Dynastic I with continuation of pries-kingship and pictographic writing |

| Flood or destruction layer found in Ur, Shurrupak (Fara) and Kish |

| Bronze Age/Uruk Period with start of priest-kingship, pictographic writing and Ishtar symbols |

| Flood or destruction layer found in Ur, Khrabeh Shattani and (probably) Kish |

| Chalcolithikum/Ubaid (last stone age stratum where seals used but writing and priest-kingship are still missing) |

Table 1

Facts listed by G. Heinsohn as evidence for a Flood event in Mesopotamia.

Heinsohn’s explanation is based on in-depth psychology and, in my perception, is extremely convincing. He succeeds in explaining rites that were previously misunderstood. A short passage from his work summarizes his approach:

The major sacrificial cults turn out to be collective healing rituals for communities that have become half crazy, or ‘senseless with misfortune’ (Boulanger) 34 through the action of global catastrophes. The rage directed against the victoriously aggressive nature, which mankind cannot constructively discharge by attack, flight or negotiation, is, so to speak, being pushed back at them, down their throats.

Within the ritual. it is used in an organic fashion. Now the collective, in need of healing, does to human or animal actors representing the force of nature ‘the unpleasantness which itself has experienced, and in this takes revenge upon the person of its representative’.

…

Cosmic collisions of inorganic lumps of matter have been viewed frequently, from an anthropomorphizing or bestiomorphising angle, as duels between warriors, beasts, or fabulous creatures. The end of the catastrophe is seen as the victory of a celestial fighter or a deity, when another ‘loses’ or ‘dies’.

..

In this context, the killed being—man or animal—represents the deity in the same sense that an actor represents King Lear on our theatre stage.

In line with this sophisticated thesis, Ev Cochrane describes the rite of a Great Plains Indian tribe (Skidi Pawnee) in which a young woman, kidnapped raiding a neighboring camp, is sacrificed to the goddess Venus.35

Heinsohn underpins the global catastrophe cited as the cause of subsequent trauma for society as a whole with archaeological and geological facts that prove a global flood.

Inanna the Kingmaker

The symbol displaying the goddess Inanna has survived from Sumer until far more recent times and developed into an allegoric relevance. It became the symbol of the ruler’s power, officially endowed to him or her by the divine representative of the goddess, a priest or priestess. Later than in historic Mesopotamia, as well as in other cultures, the investiture of a new king took place by an acknowledgement granted to him by a higher being in a symbolic act.

After pointing out Inanna’s significance in the enthronement of a ruler, it remains to be explained how it came about that a ruler was legitimized by this act.

Again, a look at the celestial event helps. To me, a religiously motivated misperception was the cause. A naïve believer can easily come up with this idea if devout to heavenly events. He noticed that the bride (Inanna) maintained her orbit after the glaring (marriage) event almost unchanged. Only there was no trace of the bridegroom to be seen anymore. The bride had united with her groom at the wedding and proved now to be the dominant part. On the other hand, she had now lent the missing husband outstanding splendor.

Let us investigate the event as it took place in a feudal society. At his enthronement, the king followed in the footsteps of the heavenly bridegroom, but at the price of being united with and serving the goddess from now on. Through the symbolic union with the goddess, he gained Dumuzis splendor and outshone all his subjects.

This assumption of mine is explicitly confirmed in the following lines of a hymn to Inanna. It is she who grants the power: 36Mistress, you have given your strength to him who is king. Ama-ucumgal-ana brings forth radiance for you.

This next quote makes it even clearer: 37

She embraces her beloved spouse, holy Inana embraces him. She shines like daylight on {the great throne dais} {(1 ms. has instead:) the throne at one side (?)} and makes the king position himself next (?) to her like the sun.

As our ancestors were very pragmatic people, Inanna’s marriage to Dumuzi was viewed as a reciprocal transaction. The ruler gained power and splendor, Inanna his service. To refasten the contract, the union was renewed every year in a sacred game in which the king, in the role of Dumuzi, married the goddess Inanna and consummated the marriage with a priestess of Inanna in a most pragmatic public sexual intercourse. The ruler renewed his claim, and the subjects conceded power to the goddess’ husband.

The importance of the goddess as an emanate of divine power on her husband is described in a Babylonian hymn with the following words: 38She embraces her beloved spouse, holy Inana embraces him. She shines like daylight on {the great throne dais} {(1 ms. has instead:) the throne at one side (?)} and makes the king position himself next (?) to her like the sun.

Their king, now the husband of a goddess, made the subjects hope for the blessing of his spouse, a real goddess, for whom the king was again appointed as her deputy.

Once established as a rite and approved by the priests, this trick spread as it ensured power in easy measure and over and over again.

Final Remark

This is where the story of Dumuzi and Innana ends after a great mystery of ancient religions has been solved.

A final word for the logbook: We should think of prehistory in simpler, more literal and realistic terms than the verbose self-appointed Generals of history and religious studies would like us to believe. In the end, they know factually little but make themselves important through gossip—a pseudo-scientific miracle that functions against all good sense.

References

1 M. Brasseur de Bourbourg, “S’il Existe des Source de Histoire Primitive du Mexique“, https://archive.org/details/silexistedessour00bras/page/82

2 The Exaltation of Inanna· By William W. Hallo and J. J. A. van Dijk, Yale University Press (1968), p. 15-17

https://babylonian-collection.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/Hallo_Van%20Dijk%20(1968)%20-%20Exaltation%20of%20Inanna_YNER%203.pdf

3 https://www.gatewaystobabylon.com/myths/texts/enheduanna/ninmesara.htm

4 Sumerian storm god

5 https://smarthistory.org/warka-vase/#:~:text=The%20Warka%20Vase%2C%20one,invasion%20of%20Iraq%20in%202003.

6 Ev Cochrane, The Many Faces of Venus, Zanzara Press, Ames (2022), p. 19

7 Ev Cochrane, The Many Faces of Venus, Zanzara Press, Ames (2022), p. 19

8 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Halebopp031197.jpg

9 Ev Cochrane, The Many Faces of Venus, Zanzara Press, Ames (2022)

10 Morris Jastrow, Revue Archéologique, Quatrième Série, T. 17 (1911), pp. 271-298, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41021741

11 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dust_jets_in_comet_Hyakutake_-_Eso9623d.jpg

12 Ev Cochrane, https://www.maverickscience.com/wp-content/uploads/Inanna-The-Queen-of-Heaven.pdf

13 Inana and Iddin-Dagan (Iddin-Dagan A), https://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section2/tr2531.htm, lines 1-16

14 Ev Cochrane, The Many Faces of Venus, Zanzara Press, Ames (2022), p. 14

15 https://monstrid.wixsite.com/monstrid/items/huldra

16 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kudurru_Melishipak_Louvre_Sb23_n02.jpg

17 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ibbi-Sin_enthroned.jpg

18 Sketch is drawn according to https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arc-1978-ac78-9464_copy.jpg

19 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lion,_Serengeti_National_Park_(48788336273).jpg

20 C.T. Russel und O. Vaisberg, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/23597515_The_interaction_of_the_solar_wind_with_Venus

21 https://www.soptah.com/pages/kemetic-symbol-guide

22 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Evenisation.jpg

23 https://www.worldhistory.org/ishtar/

24 Ev Cochrane citing R. Williams Religious Beliefs and Cosmic Beliefs of Central Polynesia, Vol I, Cambridge (1933)

25 Milton S. Terry, The Sibylline Oracles, Book V, 658-664; https://ia903108.us.archive.org/9/items/sibyllineoracles00terruoft/sibyllineoracles00terruoft.pdf

26 https://ia600203.us.archive.org/23/items/onlatinlanguage01varruoft/onlatinlanguage01varruoft.pdf, p. 178

Latin text:

…. id tempus dictum a Graecis ?σπ?ρα, Latine vesper; ut ante solem ortum quod eadem stella vocatur iubar, quod iubata, ….

27 https://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section4/tr4074.htm

28 A hymn to Inana (Inana C), https://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section4/tr4073.htm, lines 1-10

29 Mary Inda Hussey, Some Sumerian-Babylonian Hymns of the Berlin Collection; https://www.jstor.org/stable/528042?seq=1

30 Rabindranath Tagore, Sacrifice and other Plays, Macmillan and Company, Calcutta (1917); https://ia801404.us.archive.org/26/items/in.ernet.dli.2015.48942/2015.48942.Sacrifice-And-Other-Plays_text.pdf; p. 134, 135

31 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/53/Tzitzimitl.jpg

32 The Timaeus of Plato, https://ia600906.us.archive.org/18/items/timaeusofplato00platiala/timaeusofplato00platiala.pdf

33 Gunnar Heinsohn, https://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu/pdf/1998ncdb.conf..172H

34 Des durch seine Gebräuche Aufgedeckten Alterthums, Sechstes Buch – Ariß der Physischen und Moralischen Wirkungen der Sintflut; Aus dem Französischen des Herrn Nicol. Ant. Boulanger, Greiswald (1767)

https://books.google.de/books?id=h8FBAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA241&hl=de&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=2#v=onepage&q&f=false

Nicolas Antoine Boulanger (1722 – 1759) was a polymath engineer, scientist, linguist, philosophical historian and encyclopedist. He advocated the thesis of the traumatic origin of organized religion and political authoritarianism

35 In line with this sophisticated thesis, Ev Cochrane describes the rite of a Great Plains Indian tribe (Skidi Pawnee) in which a young woman, kidnapped raiding a neighboring camp, is sacrificed to the goddess Venus.

36 A tigi to Inana (Inana E), https://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section4/tr4075.htm, lines 21-24

37 A šir-namursaga to Ninsiana for Iddin-Dagan, lines 195-202; https://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.2.5.3.1#

38 A šir-namursaga to Ninsiana for Iddin-Dagan (Iddin-Dagan A), lines 195-202; https://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.2.5.3.1#

Very interesting. The comet swirl Venus glyphs remind me of Brigit’s Cross. Same girl?

To those who lived to see such spectacles, what must the world have been like?

Hi Bob, Even though the cross of the Irish goddess Brigid appears to be woven from reed, the symbol with its four points seems to me to represent a star rather than a tail. The functions associated with her as a goddess (healing, protection, poetry and domestic animals) are very different from those associated with Innana. Thus basically, I think no. A different girl with a minor coincidence in the symbol.

The clueless observers experienced the flashing of a planet as frightening. No doubt fear was the stronger trigger for the creation of myths than marvel. The brief change in climate will also have caused problems. An event nothing anyone had asked for.

I imagine, quite horrific, or we wouldn’t be discussing it thousands of years later.

Hello Aloys,

There is a simpler (and more trustworthy) path to connect the word inana/MUŠ₃ to Venus. It’s found opposite two others in the lexical lists: AŠ₂ and TAR. They spell out the name Ashtar which became the goddess Astarte (Canaan and Phoenician).

Orthodox dictionaries give inana/MUŠ₃ as ‘holy space’ among others. In my latest translation, it’s read as ‘sacred space’ (line 9) and ‘divider of time’ (line 43) collocated with a word that might read ‘strong wing’. (I very rarely use unexplained names.) And there is an element of both ‘cursing’ and ‘wishing’ involved in it, a sense of opposites which might well correspond to notions of dawn and dusk, but also of different seasons and ages.

Inana/MUŠ₃ also appears at least once next to the two words IŠ-TAR, source of Ishtar, another name that has appeared in modern times. The pictogram that gives IŠ can also be read as SAHAR, with meanings ‘earth, soil, dust’ on ePSD (and can be further linked to both Sahara and Isis).

Ashtar is by far the most interesting name that can be applied to the word inana/MUŠ₃ in that it actually appears in later cultures and languages as Astarte – not in all those rather dodgy Sumerian/Akkadian translations. Ishtar and Inana are totally inbred, poor things.

As I wrote in the notes concerning the word MUŠ₃, (line 43 of The Path to Sky-End, retranslation of Enki’s Journey to Nibru), Cicero gave Astarte as the fourth Venus (De Natura Deorum, Bk III xxiii). On Tyrian coins, Astarte carries a thrusting spear called a ‘hasta’. HAS is another transliteration of TAR, ‘to cut’, an element of which is TA, ‘death’ and ‘questioning’.

Hello Madeleine,

Thank you for your explanation. Frankly speaking I don’t know if it’s really as complicated as you discuss it.

The word ‘hasta’ is good old Latin and means: lance, pole, which is indeed an insignia of Inanna. But the connection to the name Ishtar seems purely coincidental to me.

I’m not familiar with Sumerian, but I have a faint memory of Hebrew. So I looked it up and found that in Hebrew, a Semitic language, the word goddess is translated as ‘aeza’, which to me sounds similar to Ishtar.

I don’t want to criticise or educate you, but my reply is more of a question, since basically I agree that etymology is often the key to an understanding of cryptic names or events, but it’s certainly not my area of expertise.

Moreover, my article is less about the etymology of the goddess’s name but more about explaining the origins of the myths surrounding Venus as an astronomical phenomenon with its subsequent religious interpretation – or misuse. On this point, your derivation of the name of the goddess does not seem to me to provide any additional clarification.