Introduction

In an earlier article on this website (Venus mythology), I discussed the myths and the current mysterious state of Venus and attributed both to the impact of a moon-sized minor planet. In the present article, I will supplement this former article by taking a detailed look at this minor planet. In doing so, I change the perspective, starting first with physics and then examining whether and how this minor planet has also found its way into myths.

In doing so, I will look at this colliding minor planet, which I will call Dumuzi in anticipation, and demonstrate that some myths can be interpreted as a report about this celestial object. Furthermore, I will show that the reports surrounding this planet are closely linked to the myths of the Venus goddess.

With the introduction of this minor planet, Dumuzi, we meet Venus’ mythical consort. Uncovering the connections provides an exciting story and shows once again how cosmic status and events are reflected in mythology. In this exploration, astronomy will provide us with decisive clues and quantitative arguments in an already formerly tried and tested manner.

Background Mythology

As explained in the previous article about Venus, I explicated that in the not-too-distant past, strange things happened to Venus, transforming it into a bright glowing planet. Myths tell us that this transformation of Venus also affected Earth, and humankind experienced an environmental catastrophe. These events, in heaven as well as on Earth, became the background of a global Venus lore. In fact, beyond myths, this catastrophe emanating from Venus has left enduring marks on human memory and shaped culture and the construction of temples and megalithic structures for thousands of years.

Given the significance of this event for mankind, there are similar myths about Venus and the goddess associated with it all over the world. Unsurprisingly, we find the same story either in its entirety or in fragments in different regions, times and cultures. In any case, our expectation regarding the consistency of global simultaneity in the Venus myths is remarkably well fulfilled. In ancient Iran, she was called Anahita, in India Kali, Inanna among the Sumerians, Ishtar or Astarte in the Levant, Aphrodite in Greece, Hathor/Isis in Egypt, Venus in ancient Rome, and Xochiquetzal among the Aztecs. The Levantine Ishtar even echoes in the name Asherah, the pre-monotheistic consort of the Jewish god Yahweh.1

In the previous article about the topic in question, we found answers to the mystery of the prehistoric existence of three extremely bright celestial objects in the firmament. According to our thesis, besides the Moon and Sun, the third shining object, which we encounter in myths and on reliefs, was a super-bright Venus glowing like a sun.

From its physical state and the surrounding myths, we were able to deduce that about 6,000 years ago, Venus collided with a moon-sized minor planet. The impact made the planet suddenly shine nova-bright. The cooling down took thousands of years. Even today, having lost its glow, the cooling persists.

However, the ancient relief depictions of a Tristar in the firmament are only the tip of the iceberg. Identifying the third partner in the Tristar reliefs as the reverberation of a major cosmic event is nice, but represents only the final act of a bigger story. We will show that the extension and concretization of our model for the transformation of Venus provides a comprehensive and consistent explanation. The solution to the riddle is hidden in the association of a god with the impacting minor planet. By uncovering and integrating the myths surrounding this prelude, we decipher a complete wreath of myths, and our theory becomes complete.

Moreover, our theory does not only uncover a riddle in human history but leads to a better understanding of the state of the planetary systems and how they developed. We are not aware of any existing proposal or approach that resolves this multi-layered story with its oddities and contradictions by assigning a real event to the myths.

The myths about the god Dumuzi

In order to fill in the missing building blocks in the full picture of prehistory, we will investigate the celestial object—and, as important, the myths about the assigned god—that brought about the transformation of Venus. (All this is resting on a prior article of mine: Aloys Eiling, Venus Mythology; https://grahamhancock.com/eilinga7/) By putting the myths in an astronomical context, we will investigate the minor planet not as a mythical figure in the world of the ancient gods, but compute its appearance in the canopy.

A lost planet in a preliterate period would have given rise to myths, art, religion and culture. Following this approach, we must concede that we refer to and rely on an erroneous chain of ancient messages that has been changed, reinterpreted, adapted to the zeitgeist or supplemented by invented arabesques in every culture and time. But the core of the story should still be recognizable.

Elaborating astronomical arguments, we will establish that the mythical partner of Venus, the dying and resurrecting god, was the minor planet which transformed Venus by collision. Depending on the culture and epoch, this god is the shepherd god, Dumuzi, the handsome Adonis or the Assyrian fertility god Tammuz.2

The god Dumuzi is a dazzling figure who was widely worshipped. His glamorous marriage to the goddess Inanna, his death at the hands of netherworld demons (when banished to the netherworld world by his wife Inanna instead of herself) and his resurrection is a very strange plot even in regard to the ancient belief in gods.3 Dumuzi’s marriage to the goddess and his death—even in the Bible where there is a brief reference to wailing women— as well as his resurrection, were commemorated in annual official celebrations.

Starting from the hypothesis that the god Dumuzi, Inanna’s consort and whipping boy, has been missing from the firmament for thousands of years, we move from the general to the specific and examine the myths as a narrative about an astronomical situation.

This approach goes along with the fact that the ancients were neither naive nor stupid; they just followed a different worldview. Their deities, even if they were conceived in anthropomorphic or animal form, were not fictitious beings but representations of cosmic forces mirrored in the attitude and appearance of their gods.

Dumuzi in the earthly sky

To understand the facts and background of the myths, we must first go back to the time when this minor planet was orbiting on an ellipse stretching from the asteroid belt to Venus’s orbital distance. Given this situation, we examine how an observer on Earth perceived Dumuzi.

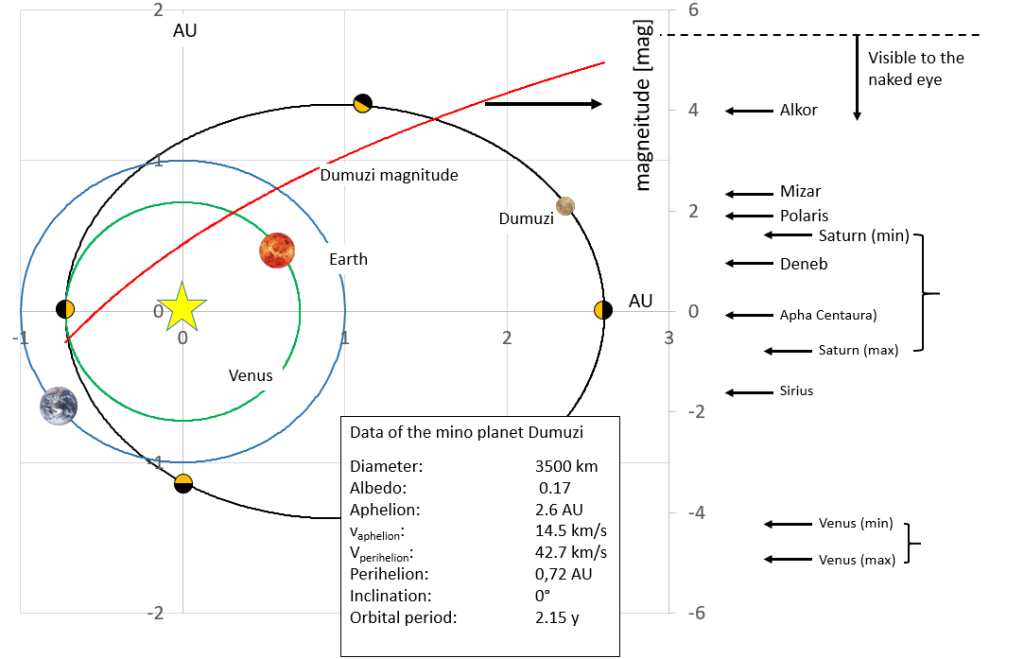

To do so, we need to calculate the brightness of a body with Dumuzi’s data in the Earth’s firmament. In the prior article about Venus, we had already defined the framework data for the collider of Venus, which now goes by the name of Dumuzi. The data chosen are listed again in Diagram 1. Unlike comparatively infinitely distant stars, the brightness of planets in the sky changes depending on their distance from Earth and the phase of their illuminated surface. If a planet in conjunction is too close to the sun, the sun outshines it, and it becomes invisible.

Trivially, all planets change their brightness depending on their distance from the Earth and the illumination phase; Venus and Mercury even disappear because they are outshone when their position gets too close to the Sun from the Earth’s perspective. However, these changes happened to the ancient watchers predictably, while the extent of fluctuations and irregularities in the brightness of Dumuzi must have been puzzling for them.

For the planets, the diameter of the Earth’s orbit defines the maximum and minimum distance relative to a given planet’s fairly circular orbits; the change in distance in the case of Dumuzi’s elliptical orbit was much greater in absolute as well as in relative terms. In the chosen orbit, the distance varies between 3.6 AU at maximum and 0.28 AU at minimum. The change in brightness was correspondingly large. In addition, as with the inner planets Venus and Mercury, the changes in brightness were superimposed by the phases in which the observer saw the illuminated hemisphere of Dumuzi. Depending on the relative position of Earth and Dumuzi, its illuminated hemisphere will have been seen as a crescent of different sizes with the limiting values dark (analogous to the new moon) and as a circle (analogous to the full moon).

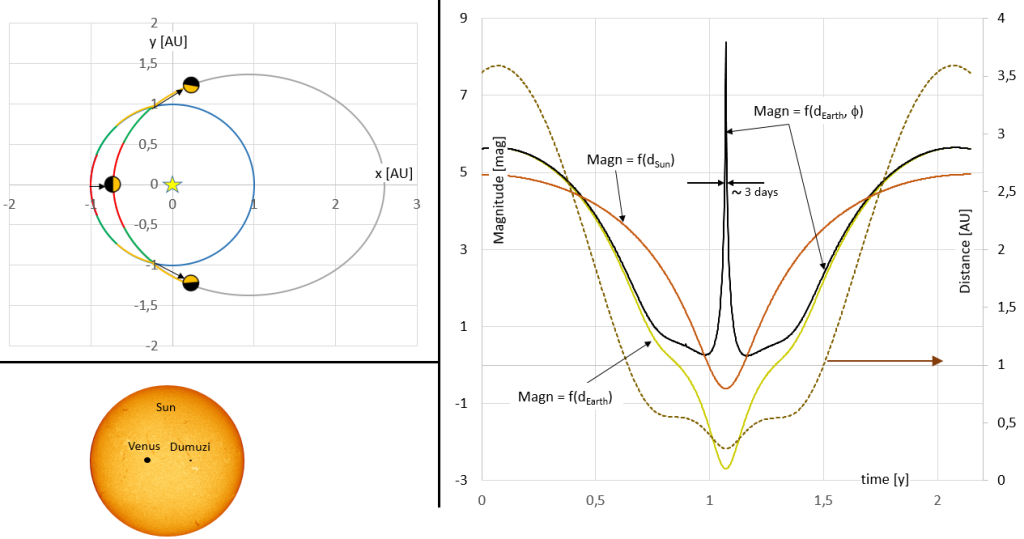

Diagram 1 Chosen orbit of the minor planet Dumuzi, orbital crosser of Mars, Earth and touching the orbit of Venus.

(Note: All objects are assumed to orbit in the same orbital plane without inclination). In red the apparent brightness of Dumuzi as a function of the distance to the Sun. As an aid to rate the apparent magnitudes, the brightness of some planets and stars is indicated by arrows to the right of the magnitude axis.

The small black and yellow colored circles on Dumuzi’s orbit illustrate the orientation of Dumuzi’s illuminated hemisphere. Depending on the position of the observer, only part of the brightly reflecting surface is visible.

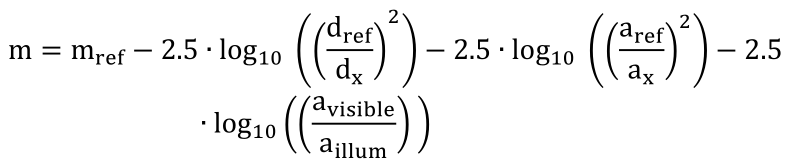

For a planet, the apparent astronomical magnitude m is calculated proportional to the quadratic ratios relatively to a known magnitude at a distance dref and the area of the planetary disk aref at the same distance. (In our calculation, we have used the asteroid Ceres as a reference body.) Following this procedure, the mathematical formula for calculating the brightness in magnitudes (the usual astronomical scale used) is as follows: 4

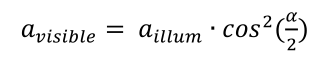

The ratio of the visible part of the illuminated hemisphere to the hemispherical surface was estimated from the angle of the line of sight. If Dumuzi moves on the other side of the sun at an angle of less than 90°, the following applies:

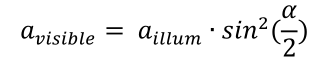

In case Dumuzi moved within the Earth’s orbit in the segment between the eastern and western quadrature to Earth, this formula holds:

At an angle of 90° half of the illuminated disk is visible from the Earth’s perspective.

As shown in Diagram 1, relative to its distance to the Sun, the brightness of Dumuzi changes along its path by more than five and a half magnitudes. At a superior conjunction position (Earth behind the Sun), its brightness is less than 5 mag, and thus, the bodies remain just visible to the naked eye. (For sharp eyes, +6 m is the very limit of visibility.) At the closest distance to the Sun, Dumuzi reaches a magnitude of -0.6, making it brighter than any star in the canopy apart from the classical planets and the star Sirius.

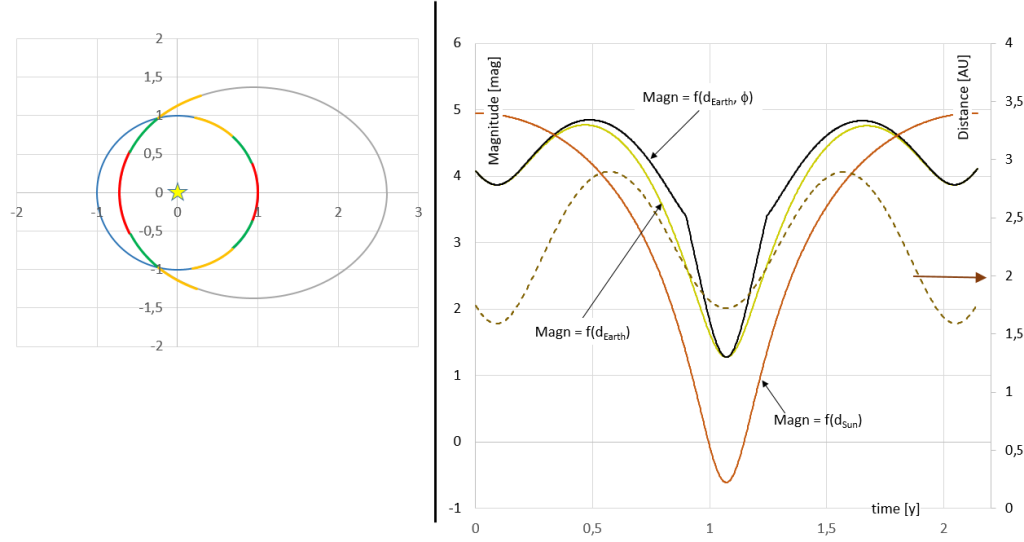

Diagram 2 shows how the consideration of the various parameters (distance, apparent diameter of the planetary disk and proportion of the visible illuminated hemisphere) influences the apparent brightness of Dumuzi.

Since the relationship between the orbital periods of the Earth and Dumuzi is not rational in our theoretical view (and probably also in reality), the possibilities for how the two bodies can position themselves relative to each other are infinite. This leads to just as much variability in Dumuzi brightness.

As shown in Diagram 2 and as discussed in the caption, Dummuzi fades—even disappears— for an observer as it recedes to its aphelion. Figuratively, the observer looks at a ‘dying’ planet, i.e., from the ancients’ point of view. After passing through its aphelion, Dumuzi slowly reappeared, i.e. according to how the ancients understood it, the planet was reborn. In any case, Dumuzi became brighter as it approached the Sun again.

This is the simplest view, which may suffice as an explanation for the layman. In fact, there is much more going on due to the phases of the visible part of the illuminated hemisphere. In this, we find details of the myths reproduced. On the one hand, this helps us understand the myths, but at least as importantly, the myths also confirm our model and even create certainty for its correctness.

As said, the shift in the line of sight due to the movement of the two bodies in relation to each other complicates the situation, as in addition to the distance to the Sun, the distance to the Earth is decisive. If the distance to the Earth increases faster than the distance to the Sun decreases, Dumuzi appears dimmer to an earthly observer, although its ‘true’ brightness increases.

We demonstrate the variability by calculating four examples, each of which details the brightness during a full orbit of Dumuzi. Firstly, we will look at the two situations in which Dumuzi, the Earth and the Sun are, at a certain time, exactly in superior and inferior conjunction, respectively (the three bodies stand exactly one behind the other on a straight line). Diagrams 2 and 3 show how the distance between Earth and Dumuzi changes in these two scenarios and what the resulting brightness curves look like.

Diagram 2 Change in brightness of Dumuzi during an orbit in which Dumuzi is at a certain time exactly behind the Earth at perihelion (inferior conjunction)

Right: The dashed brown curve displays the distance between Earth and Dumuzi.

Right: The green-yellow curve shows the brightness as seen from Earth, but still without phase correction, i.e. only as a function of distance.

The black curve corresponds to the brightness as seen from Earth.

When Dumuzi moves between the Earth and the Sun (astronomically speaking, this is a transit), the observer only sees the dark side of the minor planet. If all three bodies reside exactly on a straight line, the magnitude approaches infinity. In our iterative simulation, the data did not precisely match this state, but the effect is sufficiently clearly visible in the plot. In reality, the effect would look different anyhow, as the sun outshines the planet at an angular distance of 10° at the latest, and a transit occurs.

For reference is shown in red the plot of Dumuzi’s brightness as seen from the Sun (see also Diagram 1).

Upper left: The orbits of Dumuzi and Earth. The equally colored arc segments relate to the orbit segments traversed by Dumuzi and the Earth at a given time, respectively. Note the symmetry with respect to the Dumuzi perihelion.

Bottom left: Venus and Dumuzi during a transit. While Venus still stands out clearly as a disk against the background of the Sun, the dark disk of Dumuzi is tiny and would probably not be visible to the unaided eye, even if the Sun were dimmed. Note that the size of the spot Dumuzi generates depends on the distance between Earth and Dumuzi, i.e. it can, in some cases, become really large.

For the astronomically naive observer, who may not even have recognized the phases in the dazzling Sun as crescents, Dumuzi’s dark phase in rare cases could have become an eerie event. Because when the minor planet stands in the line of sight between Earth and the Sun, depending on the distance between the two bodies, the minor planet could have eclipsed a significant portion of the Sun’s disk. The tiny spot shown in Diagram 2 will grow in size the closer they pass each other at the point of intersection of their orbits.

It is worth noting that Dumuzi’s impact on Venus was extremely fortunate for Mars and especially for life on Earth. As the orbital cruiser of both planets, Dumuzi could have hit Mars and Earth instead of Venus. If it had impacted Earth, perhaps it would be a Venusian resident that now had our thoughts.

The fact is that the ancients could not predict how Dumuzis brightness would develop during its next traverse of its perihelion by purely empirical methods. They had to accept that in his celestial home, this god not only died temporarily but generally behaved erratically.

This erratic behavior predestined Dumuzi to become the god of agriculture and animal husbandry. Experienced farmers know that you never know how the harvest and your flock development will turn out.

The initial conditions for the second simulation of Dumuzi’s change in brightness were chosen so that the Earth is exactly in superior conjunction (on the other side of the Sun) when the minor planet passes through its perihelion. The related brightness curve is unspectacular to boring. At maximum brightness, Dumuzi is about as bright as the star Deneb.

The contemporary astrologers were probably worried about how the harvest would turn out in the next year.

Diagram 3 Change in brightness of Dumuzi during an orbit where Dumuzi is in its perihelion when Earth is in superior conjunction.

The curves shown in this diagram correspond to those in diagram 2.

Right: The dashed brown curve shows the distance between Earth and Dumuzi.

Right: The green-yellow curve shows the brightness as seen from Earth, but still without phase correction.

The black curve corresponds to the brightness, as the earthly observer perceives it. The brightness of Dumuzi as seen from the sun is shown in red.

Left: The orbits of the Dumuzi and Earth. The equally colored arc segments indicate the orbital segments traversed by Dumuzi and the Earth at the same time. Note the symmetry relatively to Dumuzi’s perihelion.

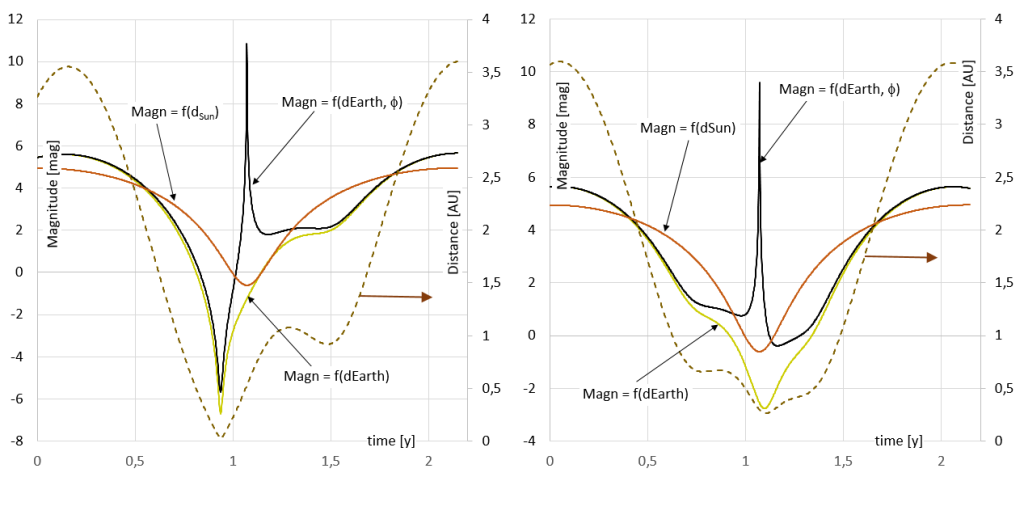

The left plot in Diagram 4 shows the case where the two celestial bodies meet at the intersection of their orbits. Dumuzi passes behind the Earth. The brightness changes from full moon bright to new moon dark within a couple of weeks. The two bodies approach each other at a distance of 4.7 million kilometers, which is about ten times the distance to the Moon. The change of 8 magnitudes (-4 to +4) takes place in 55 days, i.e. in less than 2 months. At this distance, even to the naked eye Dumuzi no longer appeared as a tiny, twinkling dot, but as an extended disk. Note, during the majority of its periods, Dumuzi was not positioned behind the Earth – as seen from the Sun.

If Dumuzi and Earth met each other close to the intersection of their orbits, the change in brightness can also occur in reverse order. In the event that Dumuzi passed between Earth and the Sun and depending on the distance, it could have grown to the size of the Moon and eclipsed part of the Sun in a black disk. Although rare, both effects are likely to have caused fear and horror among skywatchers. On this occasion, the business of fortune-tellers and prophets of disaster was surely booming.

Diagram 4 Change in brightness of Dumuzi during two randomly selected orbital periods.

The plots in this diagram correspond to the curves of Diagram 2 again.

The broken brown curves show the distance between Earth and Dumuzi.

Right: The green-yellow curves refer to the brightness as seen from Earth, but still without phase correction.

The black curve corresponds to the actual apparent brightness.

Shown in red, Dumuzi’s brightness as seen from the Sun.

In addition to the myth of the dying and resurrected god, another strange myth surrounds the figure of the god Dumuzi, namely his marriage to the goddess Inanna/Venus. After we have succeeded in solving the riddle of the interim dead and resurrected god by tracing it back to an astronomical background, it makes sense to look for an astronomical explanation for this marriage of two gods as well.

If we assume an astronomical background, the event must have been beyond imagination, as this marriage was commemorated by one of the most important festivals in ancient Mesopotamia. Every year, the marriage of Inanna and Dumuzi was celebrated with a sacred wedding rite in the form of a ‘hieros gamos’ (Spanish meaning ‘Holy Game’). In a role-play, the king of the city slipped into the role of Dumuzi, while the high priestess played the role of Inanna. The king symbolically married the goddess. The highlight of the festival was the public sexual intercourse between the two protagonists, which was considered an omen for the coming year; it answered whether the cattle would thrive and the harvest would be plentiful.

An interesting cult, but how did it come about? In times before the minor planet’s collision with Venus, prehistoric sky observers will have noticed that it was not uncommon for constellations to occur in which Venus and Dumuzi came close together and an additional, sometimes even double, morning and evening star shone in the sky. In a selected situation it could happen that Dumuzi running, when in close distance to the Sun, a bit faster in its orbit than Venus seemingly danced around the brighter planet. And so, the image of the bride and groom came to their mind.

Regardless of their joint appearance as a pair, the duration of the dark phases in which the two planets stood together or as a pair behind the Sun faded over by the Sun was similar.

This similarity and the incomprehensible relationship between the two celestial objects may have also given rise to a myth in which Inanna sends Dumuzi to the underworld, a place from which she herself can only return if someone else takes her place. Interestingly, the myth is combined with a lesson in female deceit. Inanna sends Dumuzi to hell as she can do more easily without her husband rather than her hairdresser and boyfriend.5

From an astronomical perspective, this could describe how Venus emerges from its dark phase (position behind the Sun) and sends Dumuzi, which is still bright in the sky, into its dark phase.

Looking at Diagram 4 elucidates this effect, which might have given rise to this myth. Inanna, having just become visible again herself, i.e., in the eyes of the person observing on Earth, sees the brilliant Dumuzi and sends him to the netherworld in a rage. There is no question that the change in brightness by 8 magnitudes justifies any allegory of a damnation. In this case, a most simple resolution of the background of a thoroughly misunderstood myth emerges. The annoyance of the goddess seemed all the more understandable to the neutral observer as Venus in brilliance normally outshone Dumuzi by far.

The fact that the timely sequence gets mixed up (we will refer to this later in a future article) here is more than compensated for by a good story.

Regardless of what gave rise to the myth of the dying god, the explanations, making either responsible for the distance change or the transit, are not so different, as both emphasize Dumuzi’s change in brightness.

The game of the erratic stellar rendezvous ended when the two bodies experienced a too-close encounter. This even made them collide which in turn resulted in the eruption of a planetary supernova. The minor planet had smashed into Venus. Instead of two celestial bodies, there was now only one. The two had united and merged into something larger. And this greater something was orders of magnitude different from the previous pair.

How does the description of this greater something in the myths fit into our model?

Let’s start with a quote from the book of Ev Cochrane, who has extensively studied Venus’ mythology and has compiled a treasure trove of global news and myths on the subject.6

Yet the ancient texts are quite explicit the Venus rivaled the sun in brilliance during the day: “By night she seems (as bright) as the moonlight, in the middle of the day she seems (as bright) as the sun.”

If scholars have been hardpressed to explain the ancient literature describing Venus as a waring “torch”, they are at complete loss for the words when encountering descriptions of the planet as a fire-spewing dragon.

Our model provides a trivial explanation for the scholars’ perplexity. The myths describe this cosmic impact and what followed it. Beyond this qualitative statement, our model opens up a quantitative understanding.

And there is more in correspondence. Our interpretation of Dumuzi as an astronomical apparition with the status of a god in antiquity also reveals a legend from Ancient Greece. In this myth in question, Dumuzi bears the name Adonis and Inanna is the Greek goddess of love Aphrodite.7 The legend goes that Aphrodite hides the uniquely beautiful Adonis after his birth in a box in order to have him all for herself. For safekeeping, she gave the box to her sister Persephone, the goddess of the underworld. But after Persephone opened the box and saw the beautiful boy, she refused to return him to her sister. Two goddesses fell in love with the same boy, and each wanted to keep him for herself. Zeus made the Solomonic decision that Adonis should spend a third of the year with Aphrodite and Persephone, respectively, and stayed the remaining third with neither of them but should remain for himself.

The question of the background to this strange myth gains a trivial resolution in our explanation to regard Dumuzi/Adonis as a lost minor planet. The division of Adonis’ stay into thirds shows how Adonis is assigned to the goddess of the underworld when he moves into the vicinity of Aphelion. Moving in the distance range of Venus, he then goes with the goddess Aphrodite while he is on his own when orbiting in the intermediate range of his path. Although, in reality, the minor planet spent more time in its aphelion than in its perihelion, this blurring does not detract from the clarity of this interpretation.

Once again, our derivation clearly shows that mythology and astronomy have more in common than is officially acknowledged. In our worldview, it seems strange that science and religion were closely intertwined in the myths and in the ancients’ understanding of the world. In this specific case, taking our explanation as accurate, we now understand both Astronomy and Mythology. We find a perfect match! The secrets of prehistory, which are preserved in myths, are not explained by twisted guesswork or word quibble but by natural sciences. In particular, math, here celestial mechanics, tells the truth only. Beyond doubt, it turns out, myths contain truth. Deciphering the messages of the myths becomes easy when asking the right questions—questions whose answers must be sought in the natural sciences.

Conclusion

Our model provides for the first time a reasonable and consistent explanation for what scholars of ancient religion and mythology were and continue to be so perplexed about. The myths describe the existence of a minor planet, now lost, which ended up impacting Venus. Beyond a qualitative explanation, our model opens up a quantitative astronomical understanding.

From a mythological perspective, Dumuzi’s tragic fate as a despised appendage of his wife, his reappearance as a bright planet and finally, his fusion with Venus are reflected in his transformation into the god of agriculture with the cyclical sequence of sowing and harvesting. From a mythological perspective, the traditions about Dumuzi form the prelude to the far more extensive Venus mythology, which focuses on her state as a celestial torch.

References

1 Mario Liverani, Israel’s History and the History of Israel, Routledge, New York (2007); https://archive.org/stream/MEBooks/Israel%27s%20History%20and%20the%20Histor%20-%20Mario%20Liverani_djvu.txt

2 https://www.britannica.com/topic/Tammuz-Mesopotamian-god

3 https://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr141.htm

4 https://www.atnf.csiro.au/outreach/education/senior/astrophysics/photometry_magnitude.html

The scale goes back to the Greek astronomer Hipparchus, who introduced a brightness scale with 1 for the brightest star and 6 for the star that was just visible to him. The logarithmic scaling of the modern mathematical classification takes into account that the human eye perceives chance brightness on a logarithmic scale.

5 Inana’s descent to the nether world; https://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr141.htm; lines 329 -358

6 Ev Cochrane, The Many Faces of Venus, Zanzara Press, Ames (2022)

7 Károly Kerényi, Gods of the Greeks, Thames & Hudson Ltd, London (1951),

p. 76, https://archive.org/details/dli.ministry.25806/page/n3/mode/2up

If a moon-sized object had collided with Venus 6000 years ago, there would be either evidence of the huge impact (mappable by Earth’s multiple space agencies) or a resurfacing event. But the resurfacing event occurred 300-600 million years ago, based on the craters that have accumulated since then. I could easily believe a major impact of some kind during human history, but not by something the size of a moon. Maybe something smaller but potentially much brighter, like a comet.

Thank you for your comment. The situation is indeed complicated. But fact is that the Venus mechanics, its surface temperature and surface structure speak in favor of a recent impact. For example, the number of craters on the surface of Venus is only 1/1000 of the crater density of the Moon. Even if classical astronomy rejects the idea of a recent reshaping of the planetary system, the planetological facts are different. Please note that the mass of the impactor is not an assumption, but physically necessary to stop the normal rotation of a planet. A ring-shaped structure around the equator of Venus is perfectly compatible with my impact theory (Brian E. Wood et al.; https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2021GL096302).

The time of the impacts can be derived from the cooling curve as well as from myths. See also my earlier article on this topic: https://grahamhancock.com/eilinga7/

Also if we leave physics and planetology aside, prehistoric reliefs and myths can only be explained by a Venus, at least as bright as the Moon. And the number of hints is not minor! The present interpretation of the celestial object ‘Dumuzi’ is just a supplement to the earlier discussion of this issue.

Astronomy, mythology and planetology fit too well not to have a real background.

Best regards!

How big would the Dumuzi object have been compared to the Shoemaker Levy 9 comet that hit Jupiter? That object hit our largest planet in 1994 creating a spectacular impact plume larger than the earth. Alas, had the event gone unnoticed and unrecorded we would see no trace of it today, a mere 30 year later.

Hello

I don’t know why, but I couldn’t send a reply. Now it appears to be working.

The diameter of Shoemaker Levy 9 was just 4 km, while the diameter of Dumuzi must have been around 3000 km. The ratio of masses was about one to 1 billion. Note, only an object of this mass can stop a ‘normally’ rotating planet by impact when orbiting the Sun in the same direction.

Shoemaker Levy 9 was tiny compared to Dumuzi. If a comet or asteroid of this size hits a gaseous planet, there are no lasting traces. It is not even big enough to form a ring. The situation is quite different for rocky planets. Shoemaker Levy 9 hitting the Earth would have torn a huge crater, devastated an entire continent and caused a global winter. Although smaller (about 1/3) than the Chicxulub asteroid – killer of the Dinsaurs – the comet would have been huge enough to cause a mass extinction. The energy released would have amounted to about 3 billion Hiroshima bombs. The tidal wave from an impact in an ocean could have washed over an entire continent and emptied it of all life.

Despite this cataclysm, this impact would be a mere puff compared to the impact of Dumuzi into Venus. The impact produced a flash of light that outshone the Sun for some hours by far, setting back the planet to a virginal state. The hot Venus is the afterglow we measure today, more than 6000 years later.

Best regards, Aloys Eiling

Then why is Venus’ orbit so very round? You’d think absorbing a whole minor planet and its orbit would have knocked Venus off its keester. There is software that can simulate and test your theories. I believe it’s called “Universe Sandbox”. Anton Petrov used to play around smashing planets together with it on his YouTube channel. Now he covers astronomical discovery papers.

Hello Suzanne,

Thank you for your comment, which I am happy to answer. Surprisingly, I don’t need to rely on a computer program for this simple mechanical problem. Especially since I have written an own program for my celestial mechanical computations. Your question is best answered by the following short quote from my book (to be published):

In simplest description, the fusion of the two bodies (mechanically to be classified as a rough impact) conserves the momentum of the entire system. Because of the conservation of momentum, the orbit speed of the hit planet increases as follows:

v = (m ∙ ∆v_asteroid)/(m+M)=132 m/s

In this formula m is equal to the mass of the dwarf planet, M the mass of the pre-Venus and ∆ν equal to the difference of orbital speeds (here 8.8 km/s) at the point of impact.

As a result of the impact the velocity and eccentricity of the Venus orbit increases. Simulation of the path change shows that while the perihelion distance remains unchanged the aphelion distance increases by 0.01 AU (1.6 million km). If the present simulation is assumed, the entire momentum of the dwarf planet is acting in a forward direction, then the impact considered would deform an exact circular orbit of pre-Venus into an ellipse with the eccentricity of 0.0072. The effect would be small, and a perfect circular orbit would remain close to a circle.

These 132 m/s compare to the orbit velocity of Venus, which orbits the Sun at a speed of 35 km/s. Please note in comparison to the mass of Venus (M) the mass of the assumed asteroid (m) is small and the ellipticity increases minimally. See also about Venus my article: https://grahamhancock.com/eilinga7/ The real question is, why are the orbits of most of the planets that elliptical? This issue I discuss for example in the following article on this website: https://grahamhancock.com/eilinga4/

If you have any further comments or questions, please do not hesitate to ask. I am always happy to hear from interested readers.

Regards,

Aloys