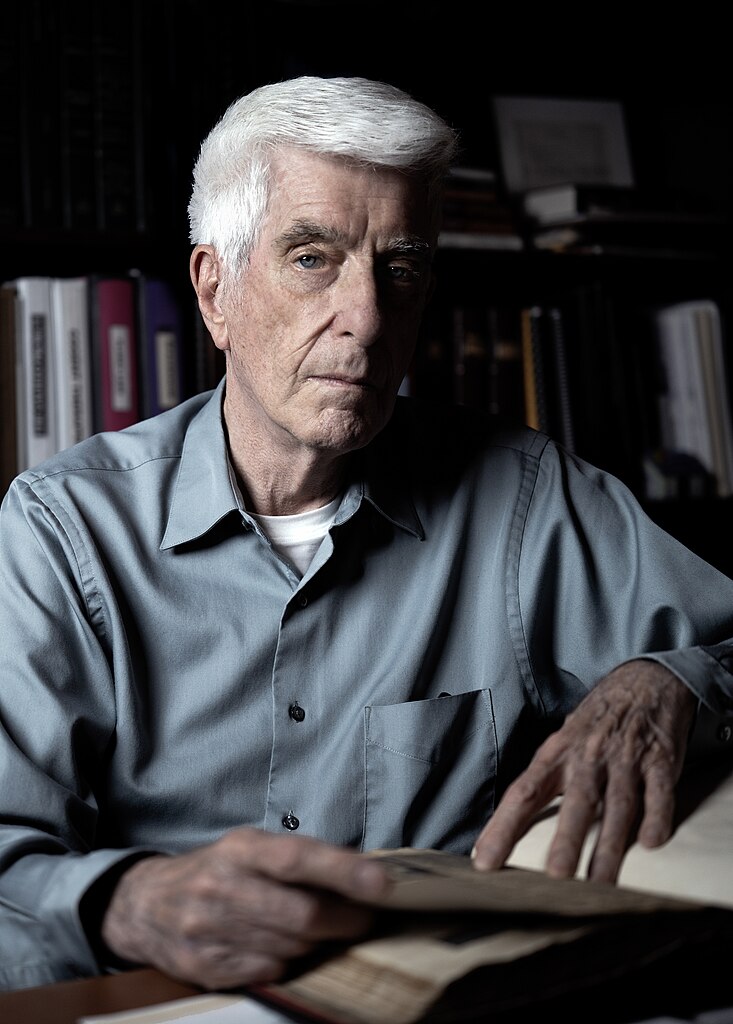

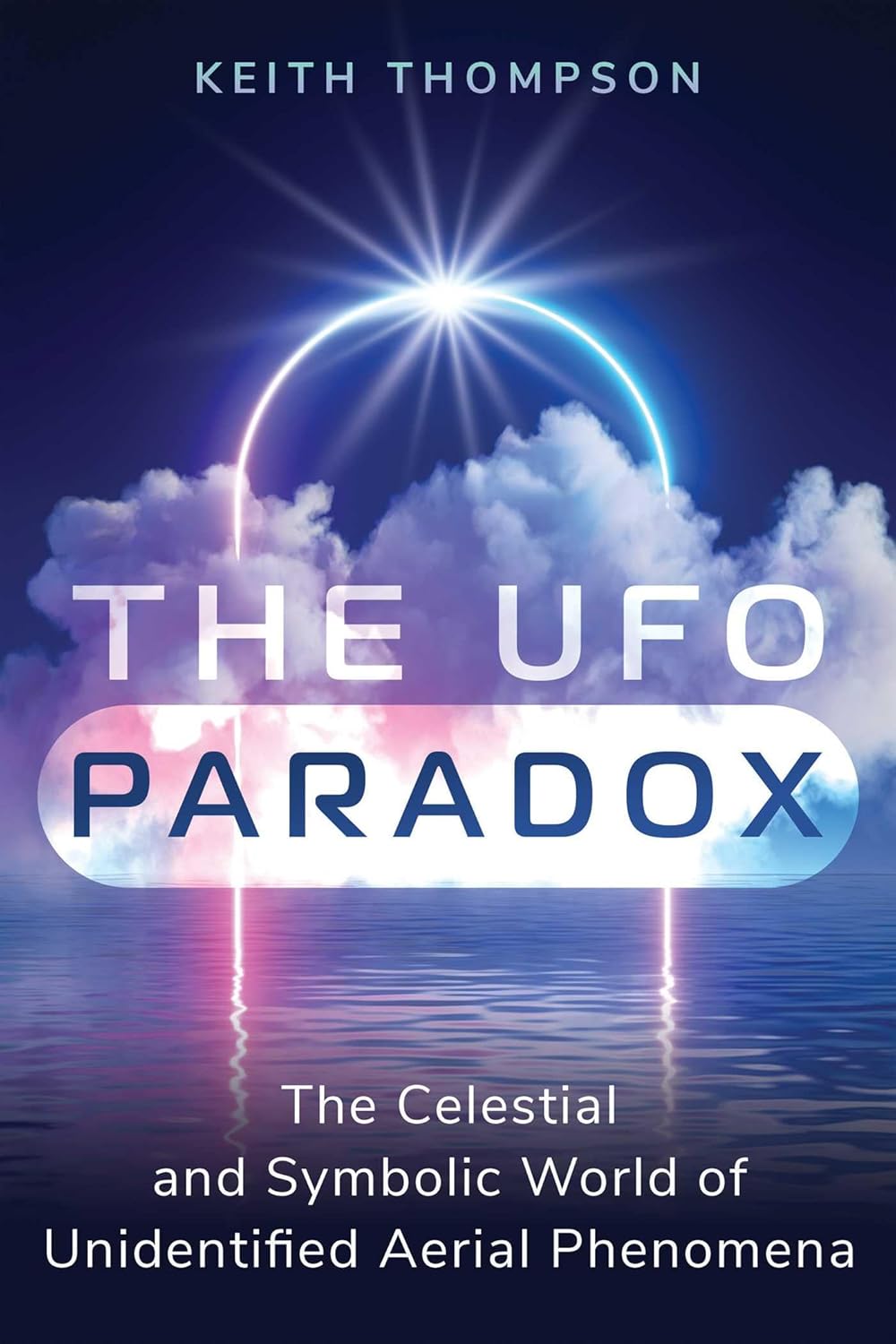

We warmly welcome Keith Thompson, author of The UFO Paradox: The Celestial and Symbolic World of Unidentified Aerial Phenomena, as our featured author this month. Keith’s book examines the immovable battleground of the UFO debate, with staunch believers on one side and dismissive sceptics on the other. A veteran UFO observer and reporter who looks beyond this deadlock, Keith focuses on the possibilities found by exploring both sides of the UFO debate and sharing profound insights and experiences from his several decades of research. Keith’s book reveals that the UFO phenomenon is decidedly real, yet perhaps not what either side of the debate expects. In his article below, Keith takes the reader on a journey of exploration into the UFO mystery, diving deep into this strange and ancient phenomenon that manifests in both the physical and spiritual realms of the human experience.

Interact with Keith on our AoM Forum here.

“A meticulously researched exploration into unidentified aerial phenomena, adopting at times a scientific lens, a philosopher’s perspective, and a journalist’s scrutiny. Thompson’s multi-lensed approach underscores the complexities and challenges inherent in the study of a phenomenon that is trying to tell us something important. Are we prepared to listen?” -Dean Radin, Ph.D., chief scientist at the Institute of Noetic Sciences and author of Real Magic and The Conscious Universe

I greatly appreciate the opportunity to be Author of the Month in Graham Hancock’s community of intellectual exploration. Even though Mr. Hancock and I practice journalism and don’t represent ourselves as scientists, I have noticed that fretful, self-appointed gatekeepers of the science community occasionally call us out for engaging in what they call “pseudoscience.” As best I have been able to figure, our offense consists of raising impertinent questions about supposedly settled facts.

Here’s my plea: Guilty as charged, let the arraignment proceed.

As the author of books about unidentified flying objects and related paranormal phenomena spanning more than three decades, indeed I have tracked events deemed quite impossible by various guardians of official truths; events that are not supposed to be possible, yet still they happen to people with diverse backgrounds, beliefs, and walks of life. My innate curiosity has led me to pursue the same question that inspired Darwin to gather fossils, Jung to probe myth, Einstein to ponder relativity, Siddhartha to leave home, and a pilot named Kenneth Arnold in 1947 to wonder about nine rapidly soaring luminous objects whose movement he compared to saucers skipping over water: What is going on here?

Debunkers Aren’t Genuine Skeptics

Over the course of my work, I have developed a keen interest in the impulse of some to explain away or ‘debunk” unresolved glitches in widely accepted paradigms whose incompleteness is demonstrated by unsolved anomalies that contradict the paradigm. I’ve come to view the impulse to waive certain observations out of bounds, off the table, simply because they don’t fit various preconceptions, as the very essence of pseudoscience. Here’s a familiar example from UFO debates:

“The witnesses didn’t experience what they say they did, in fact they couldn’t have, because what they describe isn’t possible.”

We’re familiar with statements like this from armchair scoffers who assert with matter-of-fact certainty that all UFO phenomena can be explained as hoaxes, hallucinations, or misidentifications of ordinary events; no other option. They often go through the motions of arriving at the conclusion they started with, sometimes citing “established laws of nature.” These purported laws usually turn out to be subtle articles of faith confirming a favored paradigm of reality, a particular explanatory framework that they take to be reality itself, case closed.

These dramatics unfold on media broadcasts whose producers often give celebrity naysayers the final word on controversial claims related not only to UFOs/UAP but also — in the work of Graham Hancock — ancient civilizations and alternative histories of humanity. Sidestepping data that raises questions about accepted narratives, debunkers typically resort to impugning the character of those who bring controversial evidence to the public square — as if restoring a sense of normalcy by reciting nostrums in the name of “common sense” counts as critical thinking.

What it’s not is science. Reflexive scorn for alternate perspectives is closer to crowd control, undertaken as damage prevention for a struggling worldview that has sold itself as a definitive account of nature. Knee-jerk debunking is much like religious dogmatism, as Galileo found out when he kept seeing things through his telescope that the Vatican insisted couldn’t be there. When he told his inquisitors they didn’t have to take his word for it — they could check his meticulous calculations (and have a look for themselves through his telescope) — Galileo was placed under house arrest for the remainder of his life. Centuries later, roles have largely reversed; today, the reflexive debunkers of “forbidden” evidence often speak in the name not of religion but science, in fact, a specific ideology of science driven by faith-based materialism that declares consciousness to be “the hard problem,” when in fact consciousness is the one empirical fact of existence, “the only carrier of reality anyone can ever know for sure,” in the words of philosopher Bernardo Kastrup.1

After many years on the UFO beat, I often turn to these words from the poet Rilke: “We must assume our existence as broadly as we can.” To take in all that humans experience, the perplexing and most enigmatic, even the unheard of and the seemingly impossible, without anxiously explaining it away, “is at bottom the only courage that is demanded of us.”2

An Empiricist is Born

I was twelve when I first heard of UFOs. News media, ranging from our small-town paper to prime-time national TV, were lit with reports of strange sightings in the skies over the Ann Arbor region of Michigan. Sheriff’s deputies told of seeing disk-shaped objects flashing, starlike, red and green across the dark morning sky at fantastic speed. The media frenzy coincided with my turn to give a current events report in my northwest Ohio classroom. I chose this UFO sighting that stirred debate throughout the United States for over a week. It was irresistible.

Dr. J. Allen Hynek (PD-USGov)

News clippings in hand, I told my classmates about a bright, glowing object seen bouncing across a hollow near a marsh and becoming airborne before disappearing like a TV screen shutting off. J. Allen Hynek, a U.S. Air Force consultant destined for legendary status in UFO studies, had flown in to investigate. After talking to witnesses and visiting several sighting hotspots, Hynek stepped up to the podium at a televised news conference and discussed a range of sightings in the area. He made passing reference to the glowing object near the marsh, which he speculated could have been, might have been . . . “swamp gas.”

Cue pandemonium.

Hynek was mortified to watch reporters leap from their seats and sprint to call their news bureaus and report (inaccurately) that he had reduced all the sightings to a combination of methane and smaller amounts of hydrogen sulfide, carbon dioxide, and trace phosphine that sometimes spontaneously combusts into bright colors near swamps, marshes, and bogs. The “swamp gas” explanation would take hold as a long-running joke in UFO circles, referring to debunkers’ strained attempts to explain away extraordinary sightings, regardless of evidence. “Weather balloon” is a close runner-up in the debunking tool chest.

During his next broadcast, CBS anchorman Walter Cronkite couldn’t hide his incredulity at Hynek’s seemingly ham-handed dismissal of all the credible multi-witness accounts. Michigan representative Gerald Ford demanded a congressional investigation. Interviews with bewildered Michiganders were the best part. “We may be rural, but that doesn’t make us rubes,” was the general tenor of their pushback.

I loved it, partly because I hailed from neighboring Ohio, but also because this was a classic case of the Expert arriving to set the Villagers straight, and the Villagers responding in kind. I made no effort to conceal my populist sympathies with the local yokels.

“So, you believe in aliens from outer space?” a classmate asked, as giggles rolled through the room. I didn’t have firm beliefs. “Well . . . that’s not my . . . some people believe that,” I said.

“What do you think they saw?” another student asked. “No idea,” I said. This wasn’t a dodge; I didn’t know what witnesses had seen, but swamp gas sure didn’t fit the descriptions. Somebody loudly whispered “swamp gas” and made a convincing fart sound. More laughter, mine included.

The next comment came from Gloria Lowry, our teacher: “I think Keith is saying it’s important to keep an open mind and ask relevant questions.”

Wow. She didn’t rescue me. She saw me. The way a person recognizes and acknowledges not only the viewpoint of another but their very presence as a contribution. It was a kind of benediction.

Mrs. Lowry continued: “Fine job, Mr. Thompson. You’ve got the makings of a good reporter, or even a scientist. Maybe a detective. Follow clues where they lead.”

If not for my teacher’s simple yet powerful affirmation to follow the evidence and to make room in my life for curiosity toward any phenomenon or subject, I can’t say with certainty I would have continued tracking the UFO controversy. That was the day I got it: I was an empiricist. This word and its liberating meanings wouldn’t enter my consciousness until college, where I encountered the thinking of philosopher-psychologist William James, who insisted anything that could be observed could be studied.

Empirical evidence for any proposition comes from direct observation, experience, or experiment, unconstrained by prior assumptions from theory, faith, or simple prejudice. Some experiences feel like mind, while other experiences feel like matter. The difference is in feeling, not in kind.

James celebrated what he called “radical” empiricism: “To be radical, an empiricism must neither admit into its constructions any element that is not directly experienced, nor exclude from them any element that is directly experienced.” I learned it isn’t necessary to reach an exhaustive understanding of a phenomenon prior to considering evidence, including experiences that seem unprecedented. In true fieldwork, both belief and disbelief can be temporarily bracketed, put aside for later consideration.

As I continued tracking UFO phenomena, the extraterrestrial (ET) hypothesis was the predominant interpretation for the sightings not diagnosed as hallucination, hoax, or misidentified mundane phenomena (planets, the moon, satellites, airplanes, and the like). “Have We Visitors from Outer Space?” was the question asked in 1952 by LIFE magazine, then America’s most widely read newsweekly.3 The phrases unidentified flying objects and UFOs were chosen by early UFO researcher Edward Ruppelt to convey neutrality about their nature, origin, and possible intent. Even so, it wasn’t long before the phrases became synonymous with “visitors from other planets” in the popular imagination. This assumption of equivalence continues to this day. “So, you believe in UFOs” is almost always heard as “So you believe in extraterrestrial life,” which translates to “Do you believe UFOs are visiting ET spaceships?” Then UFO proponents and debunkers take their familiar stands on the Kabuki dance floor.

Kripal’s Three Stages of UFO Inquiry

Jeffrey J. Kripal, author and professor of philosophy and religious thought at Rice University, speaks of three levels through which the study of UFOs seems to pass. “One assumes at the first level that the UFO is some kind of physical technology, some type of extraterrestrial spacecraft whose ‘tires’ (or landing gear) one could presumably ‘kick.’” These are the watchwords of level one: “We’ll figure it out. Just wait. Keep waiting. You’ll see.”4 Movies like The Day the Earth Stood Still and Close Encounters of the Third Kind instruct us to expect this.

My thinking began changing as new data came into view, especially historical findings indicating that similar objects have been seen from time immemorial, with their occupants performing actions resembling the “abductions” of the contemporary UFO era. Beliefs at the heart of the saucer reports have been a mainstay of history, organized around the theme of visitation by aerially inclined beings. The broad literature of religion and mythology features alien-like entities with physical and psychological descriptions that place them in the same category as events in the saucer era.

Kripal describes how this sudden turn in the evidence places the phenomenon in a new and broader context, level two. Here, one begins to suspect that the entire modern UFO phenomenon could be “some kind of living and tricky folklore, a mythological system taking physical shape right before our eyes, much as it has in any previous era.” Because now there’s not only talk of extraterrestrials and aliens, there’s “also talk of angels, demons, fairies, jinn, and spectral monsters. This isn’t an invasion. This is a haunting.”5

The machinery of binary thinking dutifully replaces one monolithic story with a new one, then declares: “Closure!” Except, the phenomenal stream of evidence keeps flowing. Just as the second level of interpretation begins to gel, still more anomalies show up to expand the boundaries, and to blur them as well. New kinds of physical stuff, like alleged implants in the bodies of witnesses. Saucer crash-retrieval rumors with ultra-top-secret status. Paranormal features including telepathy, precognition, clairvoyance, and teleportation into otherworldly craft. Debates about alleged leaked military documents from decades ago. Reports of human-alien hybrids borne of genetic engineering conducted in stealth by sinister aliens. They walk among us …

The mixture of data gets so wild and incongruous, it’s hard to stick with a literal level one or level two reading, though partisans of various camps do dig in. “It all gets to be a bit too much,” Kripal confesses. “And the mythical or symbolic phenomena just get weirder and weirder. Actually, nothing really gets explained.”6 At some point, the curtain opens to act three:

“One begins to suspect that what we call ‘science’ and ‘religion’ are just two cultural frameworks that we have invented for our own all-too-human purposes, and that neither of them really work very well in this ufological realm. Whatever is going on with the UFO ain’t science and ain’t religion. What it is, one no longer quite knows. All one knows is what it ain’t. Well, it ain’t simply objective. And it ain’t simply subjective.”7

Hard at work on my recent book, The UFO Paradox, I came across Kripal’s model, and I was struck by how closely our speculations tracked. From our differing vantage points, we had come to essentially the same conclusion: the methods of traditional science and conventional religions, and their specific ways of imagining the real, are unprepared for and ill-suited to a phenomenon that is neither simply objective nor merely subjective but is somehow both at the same time.

Grokking the Kick of Discovery

I’m familiar enough with the UFO field to understand this is not the kind of news that many “established” researchers find encouraging, especially those awaiting imminent resolution. When Kripal says, almost in passing, “What it is one no longer quite knows,”8 I get even more enthusiastic to stay on this beat. But not because I’m expecting some final Disclosure of the kind that has kept ufology reciting for nearly eight decades, “Any day now, the lid on the government cover-up is gonna blow sky-high,” and magically weaving every loose thread into a comprehensive and unambiguous tapestry that leaves prevailing paradigms intact. No, what keeps me at it is something else, deeper than a common panacea yet also something immediate and palpable. It has a lot to do with grokking.

In his novel Stranger in a Strange Land,9 the novelist Robert Heinlein introduced a four-letter verb, grok, as in: “I grok in fullness.” There’s no exact definition, but the essence of “to grok” something, anything, no-thing, is to understand intuitively, to empathize or communicate sympathetically with deep appreciation. When I encountered Heinlein’s novel, this strange syllable conjured a prolific sense of freedom and potentiality in the underlying nature of things. My own experiences of the extraordinary over many years have shaped my work as a writer around the idea that the limits of human growth aren’t fixed, that we have unrealized capacities for exceptional functioning—and that our understanding of reality is far from complete.

When Personal Experience Resets the Gameboard

As a journalist, my practice has been to write about subjects other than myself. With age comes a natural desire to put more of one’s perspective on the table. Though The UFO Paradox isn’t a personal memoir, it seems fitting to relate a couple of experiences that decisively changed my life and even my sense of personhood. Doing so may help you grok how I came to depart from many widely held assumptions about the happenings that fly under the banner of the acronym UFO.

In my early teens, I used to climb onto the roof of our family house, unbeknown to my parents and unseen by anybody on the sidewalks and streets below. One time, lying on my back gazing into deep sky with no purpose or desire, I suddenly experienced being everywhere at once yet nowhere in particular. I was inexplicably surrounded by a brilliance that blazed through me and seemed to lift me beyond space and time. Any sense of distance between me and everything else was nonexistent. At the time, religious ideas weren’t prominent in my life — we were a nominally religious family; it was good for good people to be seen at church. Yet somehow, I knew this power originated from a source that lies beyond each of us. It also permeates everything that is. Call it God, Spirit, Tao, Soul, Buddha Mind, Divinity, True Nature, Ground of Being, Center Court, Destiny, Patterning Intelligence, Design Mind, Collective Unconscious—or simply “life’s longing for itself,” in the words of Kahlil Gibran.

I was fourteen. The experience left me convinced there’s inherent direction and purpose in life, which had to include my own. No one knew of my time on the roof or of the vistas it opened and my sense of the possibilities that seemed implicit in every instant and iota of existence. The experience became a tacit backdrop for the flow of everyday life. I later encountered subtler versions of this presence in quiet cathedrals and chapels, in the company of ancient redwoods, in the surround of stunning sunsets and squawking gulls, in the stillness of meditation retreats, always with a sense of “being home.”

Over time, I lived with a sense of split existence—part of me capable of functioning in a divided world composed of apparently separate selves, another part aware of a deeper, foundational reality that John Friedlander, an author who reframes Jane Roberts’s Seth teachings, would describe in this way:

“Our lives are nested in things that are unimaginably big. No matter who you are or when you are, the whole universe wraps itself around you and rewraps itself around you each moment. The whole universe changes its address to you each moment. No matter how small a change you make, the whole universe — and all universes — instantly change in a way that wraps around you. Not just you, of course; you, as part of the whole universe, change and wrap yourself around every other subjectivity in the universe.”10

Fifteen years after my rooftop revelation, the idea of separate selfhood took a second hit while bodysurfing in wild waters off the coast of Hawaii. Riptides took me under, and I knew I was about to die. This thought came: “Wow. Dead isn’t dead.”

This was a time when the near-death experience wasn’t yet widely known. Three years earlier, Raymond Moody had published a groundbreaking book, Life After Life, but I knew nothing of the phenomenon the book would bring to awareness. What’s more, none of my friends could relate to the change my consciousness underwent. How unrelatable this experience was, and the confused or distressed reactions when I discussed it, led me to create a personal rule that I didn’t bring it up.

The experience was a totality-grok beyond anything imaginable. A vast sense of presence landed like a cosmic file that has been “unzipping” ever since. In college, I discovered a short treatise by Alan Watts, The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are. This led me to question the idea that we are separate beings unconnected to the rest of the universe. My near-death experience proved Watts had been spot on: the sense of being a perpetually struggling separate self is simply a tale told, believed, and lived as if true. Consciousness is everywhere and endless. We can’t be separate from it even for an instant, though we can seem to be. And in so being, each of us is also a way in which Cosmos at Large takes up residence as an individual life-situation with a unique and unrepeatable point of view. All fear of death left that day, and it has never returned.

While UFO encounters, and near-death, shamanic, and psychedelic experiences are not identical, what’s common to a broad range of supernormal experiences is the emphatic sense of getting a spiritual subpoena. Once served, you can’t hand the papers back. You’re summoned to respond. (Exactly how?) You’re expected to show up. (Where and when?) Details vary. In the face of brutal societal skepticism, count on plenty of alone time.

I quickly realized efforts to have this conversation scared people.

Sometimes, when my death experience came up, people would ask, “Did your life pass before your eyes?” Hoping this might just be the Breakthrough Conversation, it invariably became clear “life passing before your eyes” was meant only as a figure of speech. I got good at straddling worlds generally left unconnected, and I came to have a sixth sense for people who were in on this open secret about the way things really are. Goethe’s words from The Holy Longing hit the mark: “Tell a wise person or else keep silent, for the mass man will mock it right away.”

So it doesn’t surprise me that I came to feel at home with the stories of UFO people, even without a specific “UFO experience” to call my own. There’s no single format for cosmos interruptus, the experience of having your core sense of reality disrupted and reconfigured. A common or shared element across many varieties is the ringing of a bell that can’t be unrung.

For me, the rooftop clarity and the Hawaii calamity reset the game board. When the going gets strange, I tend to get jazzed. My pizzazz levels rise. At some point, most journalists encounter a cover story that doesn’t add up, some version of official reality that stirs doubts and raises questions. Identifying solely as an isolated, independent self is a hallucination that doesn’t withstand scrutiny. But it’s also a useful premise, as the song goes, for “living in a material world.” Even now, the palpable nonsense of the Michigan swamp gas explanation decades ago is as vivid as the woodpecker’s staccato tap-tapping in the tree right outside my window.

“What it is one no longer quite knows” is simply a given with the UFO phenomenon, but also — please notice — with existence at large. Open inquiry into the unknown is the flag to keep hoisting, the marker to keep planting. It is the creed I keep signing onto. For many, the idea of any “creed” is problematic. The Latin term credo is often translated as “I believe,” but its fuller meaning is “I give my heart to.”

Opening to a Universe Comprised of Experience

To new students of the phenomenon, the culmination of Kripal’s third level of discovery might suggest a discouraging dead end, a halt to further exploration. This need not be the case if open-minded curiosity has brought you to this exploration of evidence and ideas. What can end is belief in the thought that any singular approach is likely to “solve” something like this — something that routinely and robustly transgresses the boundaries between the subjective world of mind and the objective world of matter “out there.” What is this hovering, liminal “third zone” that ordinary religion and conventional science do so little to illuminate? By way of a clue, the French sociologist Bertrand Meheust throws out a highway flare:

“One is not able to envisage [the UFO phenomenon] independently from our consciousness; what is more: there can be no question of eliminating that part which the human spirit adds to it; it is, on the contrary, an essential component of the phenomenon.”11

Relinquishing the idea that UFOs can even be conceived of outside or independent of observers is not the same as locating the phenomenon solely within the human psyche, conceived of as some private interior space. In ways that push the boundaries of physicalist models of science, the phenomenon suggests a co-creative context that joins observer and observed: us encountering it, and vice versa. “There is something about the human race with which they interact, and we do not yet know what it is,” writes longstanding researcher Jacques Vallée. “But their effects, instead of being just physical, are also felt in our beliefs. They influence what we call our spiritual life.”12

Jacques Vallée by Christopher Michel (CCBYSA4.0)

The day I gave my classroom report, I had no inkling of the pervasive paranormal dimensions of the UFO phenomenon, of the meaningful coincidences of events separated by time and/or space that suggest secret symmetries between consciousness and matter. As a novice to the subject, I knew of reports that UFOs affect radar, cause burns, and leave traces in the ground, but I hadn’t yet encountered accounts of UFOs reported to, “pass through walls, appear and disappear like ghosts, defy gravity, assume variable and symbolic shapes, and strike deep chords of psychic, mystic, or prophetic sentiment,” in the words of philosopher Michael Grosso.13

Each time I thought back to my teacher’s counsel to follow clues wherever they might lead, I understood that consistent evidence could not be eliminated simply because the evidence happened to challenge prevailing assumptions held by science orthodoxy as established fact. This had to apply to paranormal features of UFO phenomena, even details that closely resemble religious miracles of previous eras and diverse cultures.

Staying the Course When Evidence Gets Strange

When Esalen Institute invited me to convene a private gathering of leading UFO researchers in 1986, I looked forward to finally meeting the legendary Allen Hynek, who had departed his advisory Air Force role to study the phenomenon independently. Even though eventual health problems prevented him from attending, I had a poignant conversation with Hynek by phone prior to the conference. We discussed not only the current state of UFO research but also his memories of key turning points in his perspective toward what had become known as alien abductions. As we talked about the earliest reports of abduction, I asked Hynek if he could recall his visceral response to those early reports and their implications for further study of the phenomenon.

“I remember my feelings at the time quite well,” he said with laughter. “My gut response was ‘Oh, isn’t this just great.’” Hynek said this sardonically, and continued:

“It was one thing to take seriously reports of aerial objects that gave the impression of being under intelligent control, but now there were reports of credible humans interacting with humanoids. This complicated the whole picture, yet there was no more of a logical basis to refuse consideration of the reports than to ignore UFO reports altogether.”

Hynek added: “It never occurred to me or my colleague Jacques [Vallée] that deliberately rejecting legitimate data was an option. How could we square that with authentic science? We were suddenly faced with reports of luminous beings that found walls no impediment to passage into rooms, and who appeared to take control of the witnesses’ minds. If this is an advanced technology, then it could encompass paranormal factors as much as our own technology includes semiconductors and holograms.”

Hynek said he had not reached a definitive conclusion about whether to consider abductions as event-level happenings in the same sense that we were speaking by telephone at that moment. He realized it was possible the humanoids and UFOs represent a parallel reality that somehow manifests itself to a few of us as limited episodes. “This wasn’t the first time, and it wouldn’t be the last, that science faced data that don’t fit conventional models. In any area of basic research, various hypotheses can and must be eliminated when found inadequate,” Hynek said. “But just ruling the data of a phenomenon out of bounds in advance is never honorable. And it is entirely appropriate to speculate without reaching definitive conclusions.”14

Jung on Navigating the Mind-Matter Boundary

C. G. Jung’s study of synchronicities led him to the revolutionary view that the greater part of the psyche lies outside the personal self. Jung began fleshing out an idea that had been implicit in his theories all along: that the collective unconscious underlies not only consciousness conceived as interior life but the physical world at large. A lifelong student of Jung’s work, philosopher Bernardo Kastrup recognizes this as a groundbreaking move, “as it means that physical events are orchestrated by the same a priori patterns that orchestrate events in consciousness.”15 Kastrup says Jung acknowledges this explicitly:

“[T]he archetypes are not found exclusively in the psychic sphere, but can occur just as much in circumstances that are not psychic (equivalence of outward physical process with a psychic one).”16 To remove any doubt, Jung confirms the impulse of the unconscious to manifest beyond the psychic sphere. Kastrup continues:

“It is perfectly possible, psychologically, for the unconscious or an archetype to take complete possession of a man and to determine his fate down to the smallest detail. At the same time objective, non-psychic parallel phenomena can occur which also represent the archetype. It not only seems so, it simply is so, that the archetype fulfills itself not only psychically in the individual, but objectively outside the individual. In alliance with the Nobel Prize–winning quantum physicist Wolfgang Pauli, Jung proposed synchronicity should “be understood as an ordering system by means of which ‘similar’ things coincide, without there being any apparent ‘cause.’”17 Again, Kastrup emphasizes the significance of what Jung is up to:

“[H]e is extrapolating the natural basis for cognitive associations in the psyche to a universal basis for the organization of all events in nature. He seems to regard the whole universe as a supraordinate cosmic mind — a ‘greater and more comprehensive consciousness’— operating on the principle of association by similarity, just as the human psyche does.”18

Jung’s expanded framework opens the door to speculations about whether a “greater and more comprehensive mind” acting on a “principle of association by similarity” may be at play in UFO cases of many types; for instance, that of Charles Hickson and Calvin Parker, who prior to their famous 1973 alien encounter at Pascagoula had chosen a first site for fishing but spontaneously moved to a new one because the biting insects had gotten too intense. Or Dennis Sant, witness to the 1980s–90s sightings in the Hudson Valley, New York, who suggested something beyond mundane explanations: “From beginning to end, the nineteen to twenty minutes that I [had] viewed the craft was also a time of self-examination of myself and who I was.”19 Or the dramatic cinematic portrayal (based on real-life UFO cases) of geographically separate witnesses inexplicably drawn to Wyoming’s Devils Tower rock formation in Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

The principle of similarity is also found in everyday life: an individual discovering a telepathic empathy that no one else appreciates or hearing suprasensory music that he or she is hesitant to describe; a “zoned” athlete experiencing extrasensory perception unrecognized by coaches; the sense of seeming to cause or correct a machine’s malfunction by intention alone; the experience of spontaneously, directly, and vividly apprehending the presence of someone physically distant or dead.

UFOs as a Call from the Cosmos

In numerous traditions, calls of many kinds often precede rites of passage and spiritual emergencies, breakdowns and breakthroughs, turning points and turnarounds, leave-takings and standstills. Calls may take the form of visions, voices, illuminations, and premonitions; sometimes, they are jarring whups upside the head when subtler measures fail. The everyday grind to a greater kind of awareness, into a broader frame of mind and heart, into communion with something larger than what they’ve been settling for.

My book The UFO Paradox is an invitation to imagine the UFO phenomenon as a call from the cosmos for humanity to open to greater dimensions of reality and recognize that our understanding of the universe is still far from complete. “Whatever or whoever is addressing us is a power like wind or fusion or faith,” declares author and teacher Gregg Levoy. “We can’t see the force, but we can see what it does.”20 He continues:

“Primarily this force announces the need for change, the response for which it calls is an awakening of some kind. A call is only a monologue. A return call, a response, creates a dialogue. Our own unfolding requires that we be in constant dialogue with whatever is calling us. The call and one’s response to it are also a central metaphor for the spiritual life, and in Latin there is even a correspondence between the words for listening and following.”21

“We have here a golden opportunity of seeing how a legend is formed,”22 Jung wrote in the early flying saucer era. I very much agree. For nearly eight decades, the curiously compelling acronym “UFO” — as an idea at work in the world soul — has shaped human belief and imagination in extraordinary ways. A contemporary prodigy has emerged in our midst, enticing us with the vibrant ambivalence of its images, systematically resisting categorical explanation, fostering virulent debate, comprising a fierce enigma of global proportions.

Call me a chronicler of the wanderings of this prodigy.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Darrach Jr., H. B., and Robert Ginna. “Have We Visitors From Space?” LIFE,

April 7, 1952.

Friedlander, John. Recentering Seth: Teachings from a Multidimensional Entity on Living Gracefully and Skillfully in a World You Create but Do Not

Control. Rochester, VT: Bear & Company, 2022.

Grosso, Michael. “Transcending the ET Hypothesis.” California UFO 3, no. 3

(1998): 9–11.

Heinlein, Robert. Stranger in a Strange Land. New York: Penguin Classics,

2016.

Kastrup, Bernardo. Brief Peeks Beyond: Critical Essays on Metaphysics, Neuroscience, Free Will, Skepticism and Culture. Winchester, UK: IFF Books, 2015.

______________. Decoding Jung’s Metaphysics: The Archetypal Semantics of an Experiential Universe. Winchester, UK: IFF Books, 2019.

______________. Meaning in Absurdity: What Bizarre Phenomena Can Tell

Us About the Nature of Reality. Winchester, UK: IFF Books, 2011.

Jung, C. G. Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Sky. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978.

Levoy, Gregg. Callings: Finding and Following an Authentic Life. New York:

Three Rivers Press, 1997.

Murphy, Michael. The Future of the Body: Exploration Into the Further Evolution of Human Nature. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam, 1992.

Vallée, Jacques. Dimensions: A Casebook of Alien Contact. Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1988.

Vallée, Jacques. Passport to Magonia: From Folklore to Flying Saucers. Brisbane: Daily Grail Publishing, 2020.

1 Kastrup, Brief Peeks Beyond, 12.

2 Murphy, 1.

3 LIFE, 1952

4 Vallée, Passport to Magonia, 7.

5 Ibid, 7-8.

6 Ibid, 8.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Heinlein, Stranger in a Strange Land.

10 Friedlander, Recentering Seth, 64-5.

11 Kripal, Authors of the Impossible, 211.

12 Vallée, Dimensions, 290-1.

13 Grosso, Transcending the UFO Hypothesis,” 9-11.

14 Hynek, comments from a telephone interview with the author, November 1985.

15 Kastrup, Decoding Jung’s Metaphysics, 62.

16 Ibid, 63.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid, 69-70.

19 Kastrup, Meaning in Absurdity, 3.

20 Levoy, Callings, 2.

21 Ibid.

22 Jung, Flying Saucers, 6.

“Human experience is either real or unreal. It is either objective or subjective, this-worldly or other-worldly. No, it is not! Human experience is often far more complex and difficult to fathom than we are to imagine. Thompson knows this and shows it. The UFO Paradox is an effective antidote to easy explanations, simple binaries, old habits of reasoning, and dead-end thinking.” -Dale C. Allison Jr., author of Encountering Mystery and The Luminous Dusk

“This book is a call from the cosmos that is fiercely alive, weirdly involved in our own forms of culture and consciousness, and beyond any of our conventional religions and sciences. Reality is not what we think it is. Nor are we. Human beings manifest supernormal powers in a supernatural world that is much bigger than we think, and maybe than we can think. Keith Thompson shows us all of this, and so much more, in a new book that is now one of our finest confrontations with the baffling truth of the UFO, which is really a paradox shattering our assumptions, whatever those are.” -Jeffrey J. Kripal, author of How to Think Impossibly

“Keith Thompson is both a scholar and a journalist that has been on the scene working hand in glove with many of the key investigators in this elusive field. He brings to this inquiry a deep understanding of the mythic and paranormal dimensions of reality. His exploration of the UFO mystery has been colored by an appreciation of the larger dimensions of human existence, triggered by his own near-death experience. This book has achieved something rare in UFOlogy lore: a near-perfect balance of the physical and nonphysical dimensions of the phenomenon.” -Jeffrey Mishlove, Ph.D., host of New Thinking Allowed

“Quantum mechanics, consciousness, cognition, Socrates, and a welcome dose of philosophy are all part of The UFO Paradox. As entertaining as it is brilliantly written, Thompson—one of the most astute writers on this topic—takes us through some of the most famous UFO cases of the modern era, giving us a fresh look at the data and how these cases touch on the most important questions of our humanity. Highly recommended.” -Jim Semivan, CIA National Clandestine Service (retired) and recipient of the CIA Career Intelligence Medal

“The UFO Paradox stands as one of the finest dives into the deep end of strange phenomena and all that is out there. From his own lifechanging near-death experience, through the labyrinthine history of the UFO field and its luminaries, presenting a transcendent metaphysical worldview far beyond simple nuts and bolts, Thompson conducts like a maestro, synthesizing a hall of mirrors with great wisdom and a unique perspective. Utterly captivating and impossible to put down.” -Josh Boone, filmmaker and director of The Fault in Our Stars

Hello Keith

Your remarks about debunkers are spot on. “My book The UFO Paradox is an invitation to imagine the UFO phenomenon as a call from the cosmos for humanity to open to greater dimensions of reality…”

My own research forces the same conclusion, and I’ve used A.I. to separate the debunkers from legit skeptics. Although my data concerns a US audience,the chats I have with an AI peer review team maybe of interest.

See nflscience1.wordpress.com

We’ve discovered the Sun’s secrets, but the Sun remains unaware of our existence. We’ve uncovered the Universe’s birthdate, but the Universe remains oblivious to our presence. Do we still believe we’re insignificant? If the universe is a projection of a higher-dimensional realm, often referred to as Heaven or God, the Big Bang might have made us the sole civilization in the Universe, and there could be a profound reason for that. Earth-like planets orbiting red dwarf stars are lifeless worlds due to the prolonged high flare rates of the parent star that would deplete the atmosphere. With red dwarf stars, most of them binary systems, comprising about 80% of the universe, the universe might be teeming with lifeless worlds. Even if the other 20% of a trillion galaxies is 200 billion galaxies with non red dwarf stars with an unimaginable number of planets that could harbor life in general, that does not mean cognitive life. Earth is one of those planets that supports life, but without the now extinct primates, it would have been an animal kingdom.

I want you to know that I am not a religious fanatic or an atheist, I always keep up with the new discoveries of scientists in different fields. But I also believe that our universe with three spatial dimensions could not have been born from nothing, as Hawking suggested, simply because nothing comes from nothing, therefore creation must be “top-bottom”, not the other way around. String theory postulates “extra dimensions”, so if the “top” has extra dimensions, then that world is infinitely intelligent and intentionally created the seeds of our civilization,

The odds of winning Mega Millions jackpot are 1 in 302,575,350, and the odds do not change based on the amount of tickets sold. The population of the United States (LIVE) a few minutes ago was 346,574,894, so think about it, I could live millions o[on millions of lives and never win the jackpot.