It is our pleasure to welcome Todd Subritzky, author of Regulating Cannabis: Towards a Unified Market, as our featured author for December. Todd’s book provides extensively researched insights into global cannabis policy and is a comprehensive handbook for anyone interested in the legalisation and regulation of cannabis. In his article here, Todd explores the unique relationship humans have with cannabis and investigates the nuances and complexities of cannabis regulation that is all too often simplified in public discourse.

Interact with Todd on our AoM Form here.

Contents at a glance

Including analysis of hundreds of pages of government documents, almost 1000 media articles, and interviews in the field with over 30 senior government officials, industry executives, and front-line public health representatives, together with over 800 academic references, this meticulously researched book is the definitive account of real-world cannabis policy implementation.

At a time when cannabis legalisation is spreading across an increasing number of jurisdictions globally, this book cuts across the noise and presents a factual account of issues faced by regulators in the real-world context of Colorado. It can be read as an evidence-based handbook for regulators and should be a first port of call for anyone interested in the legalisation of cannabis.

The book also features a number of papers published in academic journals based on the PhD research of the author. The commodification of cannabis vs the craft approach together with the entanglement of the medical and recreational markets are two of many topical themes discussed in detail.

Multiple recommendations relevant for other jurisdictions considering the legalisation of cannabis are presented. Recognising the limitations of harm reduction approaches that cannot conceptually conceive beneficial aspects of cannabis consumption, a new framework, the spectrum of wellness is proposed as an alternative in Appendix 1 of the book.

Kind words for Regulating Cannabis …

“This book clearly demonstrates authority in the field of international drug policy and draws predominantly on the latest evidence in doing so. It is a substantial contribution to an emerging policy issue with a plethora of new knowledge displayed throughout. Overall, I found this to be a vital addition to the canon of knowledge regarding cannabis policy change”

Dr Mark Monaghan

Head of the Department of Social Policy, Sociology and Criminology, University of Birmingham

“The author has broadened the understanding of cannabis regulation when it comes to conflicts between consumer protection, private profit, and public health. He has successfully applied and enriched several theoretical concepts in the context of cannabis legalization, especially when it comes to ‘the elephant in the room’ – the wellness potential of cannabis on legal markets”

Vendula Belackova, PhD Drug Policy Researcher & Adjunct Senior Lecturer at the Social Policy Research Centre, University of New South Wales

‘Recreational dispensary in Denver, Colorado’ by My 420 Tours (CCBYSA4.0)

What is cannabis?

There are thousands of varieties (technically chemical varieties or chemovars but commonly called ‘strains’) within the genus cannabis sativa with distinct cannabinoid and terpenoid profiles that impact consumers in different ways (Cervantes, 2015; Leafly.com, 2018; Lenson, 1999; Werner, 2011). In addition to this, there are a variety of methods to consume the plant including smoking, eating and topical application. Not surprisingly, therefore, the study of cannabis is complex.

Tens of thousands of books, papers, and reports over centuries, even millennia, have been written, verbally handed down or sketched into rock regarding its unique history as a herbal remedy, industrial fibre, religious aid, food, hedonic intoxicant, and weaponised agent of chemical warfare (Booth, 2005; Earleywine, 2002; Estren, 2017; Herer, Conrad, & Osburn, 2007; Herodotus, 440 BC/2016; Jay, 2010; Ketchum, 2012; Lee, 2012; Mills, 2003; Solomon, 1970). Indeed, “it is only in the last century that quality control issues, the lack of a defined chemistry, and above all, politically and ideologically motivated prohibition relegated cannabis as planta non grata” (Maccallum & Russo, 2018, p.12). The spectrum of opinion around cannabis appears to range from it being a ‘miraculous cure-all’ through to being the ‘root of all evil’ (Abel, 1943/1980; Clarke & Merlin, 2016; Crowley, 2016). This polarising aspect of the plant is a consistent theme that was identified when reviewing the literature on this topic.

There exists enormously diverse material related to cannabis in terms of (in no particular order) cultivation techniques, breeding strategies, pharmacology, ethnopharmacology, botany, religion, entheogens, ethnobotany, neuroscience, molecular biology, biogenetics, history, psychology, psychopharmacology, horticulture, political strategy, public and holistic health, archaeobotany, and cultural impact (Cervantes, 2006, 2015; Chasteen, 2016; Clarke, 1993; Indian Hemp Drugs Commission, 1894/2010; Lee, 2012; Merlin, 1973; Moreau, 1845/1973; Rosenthal, 2010; Shulgin, 1991; Thomas & ElSohly, 2016). Descriptions of cannabis are also prominent in the digital world. For example, a search for cannabis or marijuana in Google Scholar produced half a million results, there were over 200,000 related listings in the Proquest database, and 25,000 relevant titles were found on the topic at PubMed, the online database for the US Library of Medicine. Despite this wealth of material, even more knowledge may have been disposed of for fear of providing incriminating evidence to authorities in the age of prohibition (Brady, 2013; Smith, 2012), and is therefore likely lost to the general public.

The endocannabinoid system

With the discovery of the endocannabinoid system (ECS) in the 1990s, scientists began to understand how cannabis and specific cannabinoids influence the human body (Mechoulam, 2006). While this point is usually discussed in the context of medical cannabis, it is also relevant to recreational consumption. For example, Solinas, Goldberg, and Piomelli (2008) noted that evidence suggests the ECS plays an important role in signalling reward events in the brain and specifically described the involvement of cannabinoid receptors in this process of pleasure creation.

Scientists believe that the ECS evolved in primitive animals approximately 600 million years ago and it has been called one of the most significant medical findings in the 20th century (Russo, 2016). It is an important system of the human body and understanding its functions is central to understanding how and why cannabis can be both an effective medicine and a recreational pleasure. The human endocannabinoid or endogenous cannabinoid system impacts both peripheral processes and the central nervous system (Mechoulam & Parker, 2013).

According to Russo (2016, p.594), the ECS is “a unique and widespread homeostatic physiological regulator … that performs major regulatory homeostatic functions (principally the maintenance of internal equilibrium) in the brain, skin, digestive tract, liver, cardiovascular system, genitourinary function, and even bone”. Other scholars have prescribed even more functionality to the endocannabinoid system such as it being the modulator of fertility, hunger, and ageing (e.g. Blesching, 2015; Maccarrone, 2005; Viveros, de Fonseca, Bermudez-Silva, & McPartland, 2008).

The ECS consists of a network of naturally occurring endogenous cannabinoids – in other words, the body naturally creates cannabinoids to deal with an imbalance within the human body. In addition to these naturally occurring cannabinoids in the body, the ECS also consists of cannabinoid receptors (known as CB1 and CB2 among others) that respond to cannabinoids within the cannabis plant when consumed. At the most fundamental level, the function of the ECS has been described as ‘a lock and key’ that modulates internal activity within the body. As explained by Russo (2016) the ECS consists of three parts, namely cannabinoid receptors, endogenous cannabinoids [or endocannabinoids], and regulatory metabolic and catabolic enzymes.

Not ‘if’ but ‘how’ to regulate cannabis

Regulating Cannabis is guided primarily by public health and harm reduction principles and begins from the position that the prohibition of cannabis has not only failed by all reasonable metrics to achieve desired outcomes of reducing cannabis consumption, it has also actually increased harm to people who consume the substance. In general, there appears to be broad consensus in the literature that attempts to prohibit the drug have been disproportionately punitive, politically motivated, and ultimately ineffective in reducing problematic consumption. For example, it has been shown that an estimated 26 million people have been arrested on cannabis-related issues since federal prohibition began in 1937 in the US (e.g. Drug Policy Alliance, 2019; Marijuana Policy Project, 2015; NORML, 2017; Rolles, 2012).

Indeed, for more than 120 years, starting with the comprehensive 3000+ page Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission (1894/2010), multiple large government-commissioned studies across several nations have recommended that cannabis be taxed and regulated (or at the very least decriminalised), as the best way to manage public health risks associated with its consumption. Included among these studies are:

- 1925 (Panama Canal Zone Report)

- 1944 (LaGuardia Commission Report)

- Large inquiries in the late 1960s and early 1970s included:

- in the UK (Wootton Report)

- Holland (Baan Commission)

- Canada (LeDain Commission Report)

- Australia (Commission of the Australian Government)

- US (National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse)

- Independent inquiries continue in several countries in modern times and return similar conclusions. For example, a recent two-year inquiry in the state of Victoria, Australia reached similar conclusions

These reports did not mean to say there are no risks associated with cannabis, rather the point is to highlight that the risks as they have been demonstrated scientifically, have often been presented out of context and exaggerated (Meier, Schriber, Beardslee, Hanson, & Pardini, 2019). What unifies all of these studies is that none of the recommendations to legalise or decriminalise cannabis was implemented. Indeed, in the most recent case in Victoria, Australia (2021), the Labor Government took steps to water down the recommendations of the committee before they were released publicly. Victorian senator Fiona Patten who led the study reportedly stated: “Time and time again the committee heard that the current criminalisation approach to cannabis in Victoria is not addressing problematic use of cannabis and is in fact contributing to the harms experienced by vulnerable groups”.

Thus, it has become explicitly clear in regard to cannabis legalisation that politics, as opposed to public health evidence, is driving policy in many jurisdictions globally. As such, in Regulating Cannabis the focus is on presenting real-world, objective evidence relating to how the recreational cannabis market was implemented in Colorado, together with discussion around a range of policy alternatives, as opposed to whether or not it should be legalised.

A world-first initiative

Against this backdrop, there was huge interest internationally when Coloradans took matters into their own hands to use a direct democracy initiative to legalise cannabis in the State, thereby becoming the world’s first fully regulated market for adult use from seed to sale when it was implemented. According to media reports, it was a historic occasion that presaged a grand social and economic experiment in drug legalisation (BBC, 2014, Jan. 1; CNN, 2014, Jan. 2; Wall Street Journal, 2014, Jan. 2). Further, an article in the Denver Post (2013, Dec. 31) reported history professor Isaac Compos as stating; “It’s an enormous change … what we could be witnessing is the first major major crack in the whole drug war edifice”.

As the first US state to implement a recreational cannabis market, Colorado is furthest along the process, and therefore an important example to begin investigating early consequences of specific policy choices (Caulkins, Kilmer, & Kleiman, 2016; Room, 2014; Subritzky, Pettigrew, & Lenton, 2016). Implementation of the Colorado model provides an opportunity to go beyond speculation about what legalised cannabis might look like and what its effects might be to gather evidence on the real-world application of a recreational cannabis policy, thereby potentially informing policymakers and researchers in other jurisdictions about what not to do as well as being a blueprint for other schemes. Caulkins, Lee, and Kasunic (2012, p.1) contended the Colorado reforms were “unprecedented – no developed polity in the modern era has legalized [non-medical] marijuana”. Furthermore, Kilmer and MacCoun (2017) pointed out that the majority of the literature was necessarily forecasting and speculative based on studies of other legal drugs such as alcohol and tobacco, or founded on versions of decriminalisation in the US, and/or the de facto model in the Netherlands that has historically tolerated the retail sale of small amounts of cannabis but has not regulated the cultivation or manufacture of cannabis products.

How harmful is cannabis?

As noted above, few objective public health scholars would argue that there is no potential for the harmful consumption of cannabis. Indeed, as Graham himself has explained on these pages from personal experience, the relationship he cultivated with cannabis over many years ultimately turned into a “Green Bitch”.

Statistics show that approximately 9% of people who have ever used cannabis will meet the criteria of dependence as stipulated by DSM-5 (Lopez-Quintero et al., 2011). Furthermore, there is a general consensus in the literature that this number increases to one in six when the use career is initiated in adolescence and up to half for youth who consume high percentage THC cannabis on a daily basis, particularly for those under 13 years of age (Compton, Dawson, Goldstein, & Grant, 2013; Hall, 2015). It has been estimated that 1-2% of the total adult population is affected by cannabis use disorders and 2.7 million people in the US, aged 12 and over, reportedly meet the DSM-5 criteria of dependence (Hall, 2015; Volkow, Baler, Compton, & Weiss, 2014). For perspective, this 9% compares with estimates of dependence for people who have ever experimented with nicotine (30%), heroin (23%), and alcohol (15%) (Hall, 2015).

The second harmful issue commonly associated with cannabis consumption is mental health problems. Illnesses relating to mental health can include schizophrenia and other psychoses, depression, anxiety, and suicidal tendencies. The book reviews studies relating to the association between cannabis and psychosis generally, due to psychosis having both the widest coverage and the strongest association with cannabis use in the literature (Caulkins et al., 2015; National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, 2017). However, a key difficulty in assessing associations between mental disorders and cannabis consumption relates to whether cannabis causes the issue, or whether those with an existing mental illness are more likely to seek out cannabis for purposes of self-medication (Caulkins et al., 2015).

The literature is clear in defining an association between cannabis and psychosis. However, as noted above, when considering this issue it is important that context is retained, which unfortunately is rarely the case in sensationalist media pieces reporting studies without the necessary critique of study designs. As an example, a review of methodological strengths of relevant studies found that while an association is supported, the causality of psychosis that would not otherwise have occurred cannot be conclusively established (McLaren, Silins, Hutchinson, Mattick, & Hall, 2010). Furthermore, the association itself is weakened when studies attempt to control for common risk factors such as increased familial morbid risk (e.g. Hall, 2015; Proal, Fleming, Galvez-Buccollini, & DeLisi, 2014). In general, Hall (2015) pointed out that at the population level, the effects of cannabis consumption on psychoses are relatively small. Indeed, it is claimed that “thousands of [consumers] would have to be prevented from use for a year to prevent one potential case of schizophrenia” (Caulkins et al., 2015, p.38; Hickman et al., 2009). In jurisdictions where cannabis has been legalised, no rigorously conducted studies have identified a statistically significant increase of mental health problems associated with cannabis legalisation.

Conversely, there is no recorded death as a direct result of herbal cannabis consumption per se and as such related harm in the context of the global burden of disease is low, so context needs to be applied when considering the harms. For example, attempts to quantify and compare the contribution to the total burden of disease relating to cannabis, other illicit drugs, alcohol, and tobacco provided estimates of 0.2%, 1.8%, 2.3%, and 7.8% respectively (Room, Fischer, Hall, Lenton, & Reuter, 2010). Indeed, estimates from the start of the study indicated (conservatively) that 182.5 million people consumed cannabis globally, which consisted of 80% of the estimated total of illegal drug use at the time (Room, 2012; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2016). Thus, at the rhetorical level, cannabis plays an important role in justifying the existence of these drug treaties and conventions and it has even been suggested that when cannabis is excluded, “illegal drug use is not a global population-level issue” (Room et al., 2010, p.9).

Additionally, it is worth noting at this point that none of these studies has differentiated between the different preparations of cannabis or methods of consumption. Nuance is therefore lacking in this data, as clearly some forms of consumption are more harmful than others. An example would be smoking cannabis mixed with tobacco compared to using a dry herb vaporiser loaded with organically grown, mild dosages of cannabis.

Commodification vs craft cannabis industries

According to the late, great cannabis policy scholar Prof. Mark Kleiman, even highly commercial cannabis legalisation models such as that in Colorado are preferable to prohibition (e.g. Lopez, 2014, December 17). However, this position is not without controversy and is being tested in current times as tobacco companies make noises about entering the cannabis market, which is alarming from a public health perspective. This is nothing new, with evidence from Barry, Hiilamo, and Glantz (2014) indicating that tobacco companies have been interested in cannabis strategically since at least the 1970s.

However, not all commercial regulatory models are the same, which is something that is often missed in cannabis policy studies that tend to lump all commercial models together despite there being a wide range of approaches contained within that overarching term. Regulating Cannabis brings a level of nuance to the discussion that is not generally apparent in the literature by incorporating a second theoretical framework that considers cannabis as an agricultural commodity. The so-called ‘cannabis fragmentation spectrum’ (CFS) as outlined by Stoa (2017) from an agricultural perspective, delineates several models under the broad rubric of commercial/free-market conceptions. The CFS distinguishes between regulations that encourage the consolidation and commodification of cannabis plantations and sales outlets on the one hand and the protection of smaller-scale farmers and the creation of an artisan industry on the other. The CFS includes three components, namely commodification, vertical integration, and appellation designations. Stoa (2017, p.317) pointed out that “contrary to the views of many prognosticators, the eventual consolidation of the marijuana industry is not a foregone conclusion. In this matter, states and local governments have a choice to make”. In Regulating Cannabis this framework is applied to the Coloradan approach and discussed in the context of North American cannabis markets.

While states in the US have tended to regulate recreational cannabis in a manner more or less similar to alcohol (e.g. Caulkins et al., 2015), it has been argued that this approach “reveals a regulatory blind spot” for an agricultural product that, by some measures, is the largest cash crop in the US (Stoa, 2017, p.297). Indeed, since cannabis was prohibited long before any cultivation regulations, states now face challenges regulating one of the country’s largest agricultural industries for the first time (Stoa, 2017).

As previously discussed, a major concern with the commodification of cannabis regulation is that the industry will morph into a powerful body with significant clout to influence regulations and potentially negatively impact public health. This concern stems from lessons learned from other ‘big’ industries including alcohol, tobacco, agriculture, and pharmaceuticals (e.g. Pacula, Kilmer, Wagenaar, Chaloupka, & Caulkins, 2014).

The CFS as outlined by Stoa (2017) addresses a fundamental question, namely: should regulations be developed that permit the consolidation and commoditisation of cannabis plantations and sales outlets, or is the protection of small-scale farmers and the creation of an artisan industry a priority? First, at one end of the spectrum, cannabis is commoditised as a generic, mass-produced, and inexpensive agricultural product. As noted above, it is generally argued that the commoditisation of cannabis will lead to price collapse (due to economies of scale and technological advances), and by association, higher risk potential from a public health perspective. Additionally, price competition may force smaller farms out of business. Indeed, it has been argued that the ‘agribusiness’ model of food production in the US, even for non-intoxicating produce, is fundamentally broken, corrupted, and controlled by self-interested corporate influence to the detriment of public health and the environment (Engdahl, 2007; Nestle, 2013). As described in detail in the following chapter, while Colorado initially attempted to limit the impact of commoditisation by restricting out of state investors’ access to markets, federal legalisation is seen as a potentially disruptive force, particularly if interstate commerce were to be permitted and banking restrictions removed (Stoa, 2017). A clear example of commodification was reported in the Canadian context where a cultivation facility “the size of 19 football fields … expected to produce 75,000 kgs of cannabis annually” was approved (Cannabist, 2018, Mar.7).

However, a policy that allows commoditisation does have some advantages from a regulatory perspective. To illustrate the point, Stoa noted that while regulators in States such as California grapple with licensing 50,000 or more farmers, other states including New York, Florida, and Ohio seek to limit cultivation licenses to 20 or fewer. In this sense, regulators may license a handful of large farms, on which they can “lavish regulatory attention … to ensure compliance” (Stoa, 2017, p.321).

Second, vertical integration of the supply chain, that is, when the same firm both grows and sells cannabis, occupies a middle position on the CFS. As discussed in the next chapter, the CRCM initially opted for a vertically integrated approach. Regulatory advantages of vertical integration include reduced businesses to oversee; a simplified process to track cannabis from seed-to-sale; reduction of supply chain diversion to the black market; and improved business efficiency, which may lead to increased profitability. Disadvantages include high barriers to entering the market, particularly around significant start-up costs; amplified business risk, whereby failure of any aspect of the business may negatively impact other areas; and the potential to increase market consolidation for large firms (Stoa, 2017).

Third, at the opposite end of the spectrum, cannabis cultivation could be regulated by appellation designations similar to the US vineyard or microbrewery model. “An appellation is a certified designation of origin that may also require that certain quality or stylistic standards be met” (Stoa, 2017, p.325). The appellation model may best be suited to outdoor cannabis cultivation in jurisdictions such as Northern California, which is said to cultivate 60% of the entire US cannabis supply, as it tends to focus on aspects such as climate, soil quality, and aridity that contribute to the overall quality and uniqueness of harvested cannabis (Stoa, 2017). Just as certain grapes thrive in different climatic environments, cannabis seeds are diverse. Indeed, demand appears strong for so-called ‘landrace strains’, that originate from, and are unique to, geographic locations around the world as can be demonstrated by a popular YouTube channel with almost 100,000 subscribers and views in the 10 of millions (Strain Hunters, 2016). However, the model could be modified to include certified growing standards to incorporate indoor cultivation. This may protect the intellectual property of industries in other jurisdictions. For example, the Netherlands and Colorado have established reputations for cultivating cannabis produce that is apparently well regarded among cannabis consumers (Decorte, 2010; Leafly.com, 2018). Thus, advantages of appellations include: (i) product differentiation that may hinder commoditisation; (ii) protection of local industries’ hard-earned reputations; (iii) preventing price collapse; and (iv) consumer protection through the certification of authentic products. Disadvantages include: (i) challenges to enforce at the local level if other jurisdictions are not included; (ii) a lack of regulatory leadership at the federal level; (iii) indoor cultivation techniques may lessen the relevance of geographic appellations; and (iv) there is no guarantee that appellations would prevent consolidation of the market, even if the model allows for product diversity and hinders commodification (Stoa, 2017).

Entanglement of medical and ‘recreational’ cannabis

A theme that continuously emerged throughout the research was the entanglement of the recreational and cannabis markets. This perhaps reflects the crossover first identified in Chapter 2 describing how cannabis interacts with the human body via receptors in the endocannabinoid system regardless of whether that consumption is labelled medical or recreational (e.g. Russo, 2016).

Regulating Cannabis describes how a large portion of cannabis consumption appears to take place in a realm where medical and recreational intent overlap (e.g. Hakkarainen et al., 2017). However, it is generally dealt with as two separate issues. In part, this is due to, as Mead (2014) pointed out, international controls that dictate cannabis must be considered separately for medical and recreational use. Colorado is an example of a state in the US where the recreational market is built on a separate medical market (Subritzky, Pettigrew, & Lenton, 2016).

As an example of this overlap, in a study describing patterns of cannabis use, Pacula, Jacobson, and Maksabedian (2015) found approximately 85% of medical consumers also reported using cannabis recreationally. Furthermore, as part of a global study on cannabis cultivation trends, Dahl and Frank (2016) noted the definitional challenges of medical and recreational consumption of cannabis and found that cannabis consumers who defined themselves as medical, tended to emphasise the relieving effect over pleasurable outcomes. Chapkis and Webb (2008) identified a group of consumers who refuse to distinguish between recreational and medical consumption. Iversen (2007), moreover, pointed out that the window between an effective medical dose, and one that intoxicates, appears to be quite narrow. Indeed, it has been argued that “defining cannabis consumption as elective recreation ignores fundamental human biology, and history, and devalues the very real benefits the plant provides” DeAngelo (2015, p. 67). Well known cannabis advocate Dennis Peron reportedly stated that all cannabis consumption is medical, with the obvious exception to the rule being misuse (DeAngelo, 2015; Rendon, 2012). This view is illustrative of what Caulkins and Reuter (1997) have called the extreme social utilitarian perspective.

Examples of this entanglement in Colorado include the duplication of regulations, cultivation standards, and testing requirements. Indeed, by 2019 the two codes of regulations were almost completely aligned (Colorado Secretary of State, 2019), leading to the logical recommendation in the 2018 Sunset Review to unify the two markets in 2020 in order to maximise regulatory efficiency and minimise needlessly duplicitous regulation (Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies, 2018). Unification of the two markets has also been recommended by cannabis policy experts (Carnevale, Kagan, Murphy, & Esrick, 2017). A unified market would presumably reduce this duplication thereby removing an important barrier to market entry for small businesses and potentially shrink the black-market as a result.

Cannabis wellness: pleasure, spirituality and beyond

Several scholars have found that the overwhelming reason for consumption provided by people who use cannabis is pleasure (e.g. Duff, 2008; Webb, Ashton, Kelly, & Kamali, 1998). This is perhaps unsurprising given that an often-used description of the effect of cannabis on mood is euphoria (Ashton, 2001). As may be deduced, euphoria is not generally defined as harm per se. In this respect, the harm reduction model has been critiqued for not giving consideration to the concept of pleasure (Houborg, 2010). Moore (2008) pointed out that the term pleasure has become marginalised in discourses that seek to understand drug use. It would not seem unreasonable to conclude that many people who use cannabis may do so with an aim of enjoying it. Indeed, Earleywine (2002, p.99) noted that in practical terms, those who arrange to consume cannabis in a relaxed, safe, and comfortable environment “frequently report positive effects from the drug”.

Second, there is a long association between the consumption of cannabis and wellness practices associated with mind-body techniques including yoga, meditation and spiritual exploration. For example, Dussault (2017) contended that the use of plant medicines such as cannabis in yogic philosophy dates to the Yoga Sutras (ca. 400 CE). Based on years of self-experimentation, Dussault considers all cannabis consumption, when used in a mindful way, as medicinal (both as treatment and preventative). Furthermore, Dussault (2017, p.2) postulates that when combined with yoga, regular “moderate doses of cannabis, rather than larger amounts less frequently, are a tonic to support a powerful healing system for mental health and wellness”. This perspective is in contrast to the public health approach that views all regular and sustained cannabis consumption as high risk (Fischer et al., 2009). Dussault advocates ‘microdosing’ cannabis to find the minimum effective dose. At the time of writing, numerous firms were offering cannabis yoga classes and retreats in states such as Colorado that have legalised cannabis for both recreational and medical purposes (e.g. Cannabis Ganja Yoga Retreat, 2017).

Regarding spirituality, it was noted above this is an important component within the spectrum of wellness (Bello, 2010; Hattie et al., 2004). Spirituality can be defined in many ways. For example, Grof (2016) considered the notion of an expanded consciousness beyond limitations of space and time as spiritual. Myers et al. (2000), in contrast, contended that a feeling of connectedness to the Universe that transcends material aspects of life was an essential component of a spiritual outlook. These definitions are said to be distinct from narrow concepts of religiosity, which refer to institutional beliefs (Steiner & Reisinger, 2006). Descriptions of using cannabis to obtain spiritual states of consciousness (i.e. the entheogenic consumption of cannabis) are numerous with a history that spans millennia (Brown, 2012; Crowley, 2016; Estren, 2017; Gray, 2016). In 2017, a church was established in Denver, Colorado, with the reported aim to allow members to “consume the sacred flower to reveal the best version of self … through ritual and spiritual practice” (International Church of Cannabis, 2017, p.1). The spectrum of wellness may be a useful framework for gaining insights into the consumption of cannabis from this perspective.

Third, an apparently new development that has emerged within the spectrum of wellness is the relationship between cannabis consumption and fitness. Goldstein (2000) has argued there are multiple health-related assumptions shared by the fitness movement and the wellness industry including: (i) the notion of taking personal responsibility for health; (ii) the interconnectedness of mind, body and spirit; and (iii) a belief in the positive connotations of ‘getting back to nature’. A recent example of fitness and cannabis combining in the modern industry is the opening of the (self-reported) world’s first cannabis gym in California. According to their website, Power Plant Fitness (2017) members may consume cannabis at the gym before or after working out “in a full-blown health and wellness centre, focused on full-body integrative health, wellness and fitness”. There is little in the academic literature relating to the consumption of cannabis for fitness purposes beyond a systematic review of fifteen studies by Kennedy (2017), which concluded THC does not enhance exercise performance. However, there appears to be a growing number of anecdotal reports on the benefits of consuming cannabis for fitness purposes, particularly around the notion of increased stamina (e.g. BBC, 2018, May 31; Civilized, 2017, Feb. 20; Guardian, 2016, May 2; The Cannabist, 2017, Jun. 16; Well and Good, 2017, Apr. 3).

Towards a new paradigm that considers benefits as well as harms

Regulating Cannabis concludes that while the harm reduction framework plays an important role and has been helpful both to identify potential harms and develop strategies to reduce them, it is equally clear that, by definition, harm reduction conceptions are unable to consider potentially beneficial consumption of the drug. This is problematic when considered against, for example, the entanglement of medical and recreational cannabis described above, as presumably, when cannabis is consumed as a medicine, it is bringing therapeutic relief or benefit to consumers.

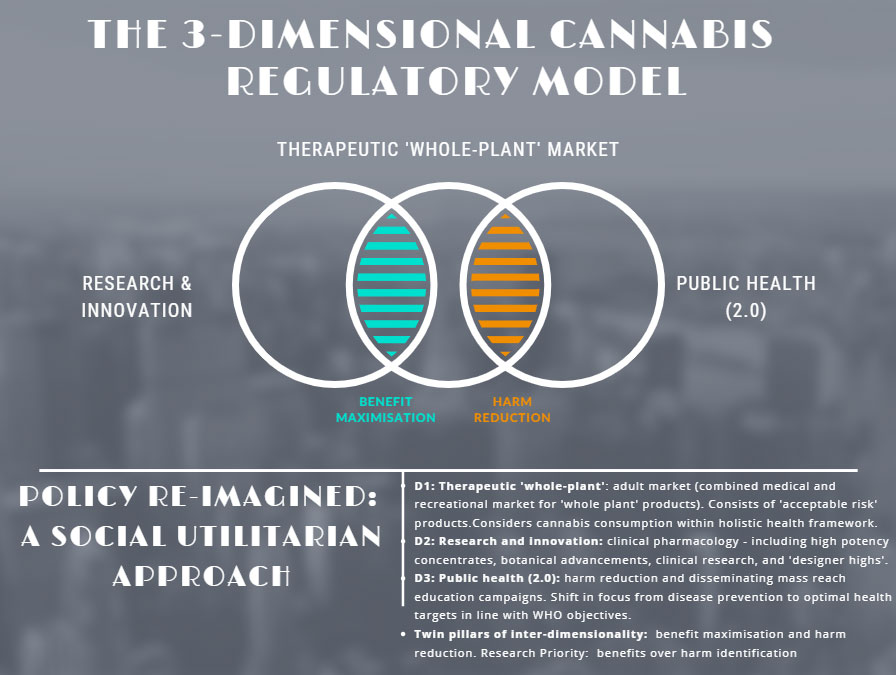

In this regard, there appears to be a significant amount of cannabis consumption that is beyond the scope of harm reduction frameworks. In Regulating Cannabis a new paradigm for cannabis research and market structure is suggested. As can be seen in Figure 9, the 3-dimensional cannabis regulatory model is based on a social utilitarian perspective and consists of three main dimensions, namely: (i) the therapeutic ‘whole-plant’ market (TWPM); (ii) research and innovation; and (iii) public health (2.0).

Caulkins and Reuter (1997, p.5) stated that “most people would exclude the benefits of drug use …” when devising strategies to reduce harm, although it remains unclear why. In contrast, the 3-D model aligns to a ‘social utilitarian perspective’, in the mould of Bentham who described utility as “the sum of all pleasure [and other benefits] that results from an action, minus the suffering of anyone involved in the action” (Theory of Knowledge, 2019, p.1).

In general, the 3-D model was conceived from lessons learned from the Coloradan scheme to minimise the risks and harms associated with higher risk cannabis, while also unlocking the potentially beneficial aspects of the drug. In the 3-D model, research and innovation would be incentivised towards finding benefits attributable to the plant – a fundamental shift away from current funding models whereby most public health research on cannabis prioritises establishing causality of harms. Such an approach may warrant further research.

References

Abel, E. (1943/1980). Marihuana: The first twelve thousand years. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Barry, R., Hiilamo, H., & Glantz, S. (2014). Waiting for the Opportune Moment: The Tobacco Industry and Marijuana Legalization. Milbank Quarterly. 92(02), 207-242.

BBC. (2014, Jan. 1). Cannabis goes on legal sale in US state of Colorado. Retrieved 13/11/2017 from http://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-25566863.

Blesching, U. (2015). The Cannabis Health Index: Combining the science of medical marijuana with mindfulness techniques to heal 100 chronic symptoms and diseases. Berkley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Booth, M. (2005). Cannabis: A history. New York, NY: Picador.

Brady, E. (2013). Humboldt: Life on America’s marijuana frontier. New York, NY: Grand Central Publishing.

Cannabist. (2018, Mar.7). Cannabis cultivation a go for giant Canadian tomato greenhouse. Retrieved 7/3/2018 from https://www.thecannabist.co/2018/03/05/canada-greenhouse-cannabis-cultivation-approved/100501/.

Carnevale, J., Kagan, R., Murphy, P., & Esrick, J. (2017). A practical framework for regulating for-profit recreational marijuana in US states: lessons from Colorado and Washington. International Journal of Drug Policy, 42, 71-85.

Caulkins, J., Kilmer, B., & Kleiman, M. (2016). Marijuana legalization: What everyone needs to know (2nd edition). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Caulkins, J., Kilmer, B., Kleiman, M., MacCoun, R., Midgette, G., Oglesby, P., . . . Reuter, P. (2015). Considering marijuana legalization: insights for Vermont and other jurisdictions: Rand Corporation.

Caulkins, J., Lee, M., & Kasunic, A. (2012). Marijuana Legalization: Lessons from the 2012 State Proposals. World Medical & Health Policy, 4(3-4), 4-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/wmh3.2

Caulkins, J., & Reuter, P. (1997). Setting goals for drug policy: harm reduction or use reduction? . Addiction, 92(9), 1143-1150.

Cervantes, J. (2006). Marijuana Horticulture: The Indoor/Outdoor Medical Grower’s Bible. USA: Van Patten Publishing.

Cervantes, J. (2015). The Cannabis Encyclopedia: The definitive guide to cultivation & consumption of medical marijuana. USA: Van Patten Publishing.

Chasteen, J. (2016). Getting High: Marijuana through the ages London, UK: Rowman & Littlefield.

Clarke, R. (1993). Marijuana Botany An Advanced study: The propagation and breeding of distinctive cannabis (2nd edition). Oakland, CA: Ronin Publishing.

Clarke, R., & Merlin, M. (2016). Cannabis: Evolution and ethnobotany. Berkley, CA: University of California Press.

CNN. (2014, Jan. 2). Colorado’s recreational marijuana stores make history. retrieved 13/11/2017 from http://edition.cnn.com/2013/12/31/us/colorado-recreational-marijuana/index.html.

Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies. (2018). 2018 Sunset reviews: Colorado medical marijuana code and Colorado retail marijuana code. Retrieved 10/11/2018 from https://drive.google.com/file/d/1QeSxuD7cqil3L5mLuInWze2BsyYpCSQj/view.

Colorado Secretary of State. (2019). 1 CCR 212-2: Retail Marijuana Regulations. Retrieved 5/4/2019 from http://www.sos.state.co.us/CCR/DisplayRule.do?action=ruleinfo&ruleId=3175&deptID=19&agencyID=185&deptName=200&agencyName=212%20Marijuana%20Enforcement%20Division&seriesNum=1%20CCR%20212-2.

Compton, W., Dawson, D., Goldstein, R., & Grant, B. (2013). Crosswalk between DSM-IV dependence and DSM-5 substance use disorders for opioids, cannabis, cocaine and alcohol. Drug and alcohol dependence, 132(1), 387-390.

Crowley, M. (2016). Secret Drugs of Buddhism: Psychedelic Sacraments and the Origins of the Vajrayāna. Hayfork, California: Amrita Press.

Decorte, T. (2010). The case for small-scale domestic cannabis cultivation. International Journal of Drug Policy, 21(4), 271-275.

Denver Post. (2013, Dec. 31). Marijuana in Colorado has a long history and an uncertain future. Retrieved 13/11/2017 from http://www.denverpost.com/2013/12/31/marijuana-in-colorado-has-a-long-history-and-an-uncertain-future/.

Drug Policy Alliance. (2019). Guiding Drug Law Reform & Advocacy. Retrieved 09/08/2017 from Drug Policy Alliance http://www.drugpolicy.org/. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6YXTjp0PE).

Earleywine, M. (2002). Understanding Marijuana: A new look at the scientific evidence. USA: Oxford University Press.

Engdahl, W. (2007). Seeds of Destruction: The hidden agenda of gentic manipulation. Montreal: Global Research.

Estren, M. (2017). One Toke to God: The entheogenic spirituality of cannabis. Malibu, CA: Cannabis Spiritual Center.

Hall, W. (2015). What has research over the past two decades revealed about the adverse health effects of recreational cannabis use? Addiction, 110(1), 19-35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/add.12703

Herer, J., Conrad, C., & Osburn, L. (2007). The Emperor Wears No Clothes: Hemp and the marijuana conspiracy (eleventh ed.). Van Nuys, CA: AH HA Publishing.

Herodotus. (440 BC/2016). The History of Herodotus – Volume 1. New York, NY: Palatine press.

Hickman, M., Vickerman, P., Macleod, J., Lewis, G., Zammit, S., Kirkbride, J., & Jones, P. (2009). If cannabis caused schizophrenia—how many cannabis users may need to be prevented in order to prevent one case of schizophrenia? England and Wales calculations. Addiction, 104(11), 1856-1861.

Indian Hemp Drugs Commission. (1894/2010). Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission 1893-94 Volume 1 Report. London, UK: Hardinge Simpole Publishing.

Jay, M. (2010). High society: The central role of mind-altering drugs in history, science and culture. Rochester, VT Park Street Press.

Ketchum, J. (2012). Chemical Warfare Secrets Almost Forgotten. Bloomington, In: AuthorHouse.

Kilmer, B., & MacCoun, R. (2017). How Medical Marijuana Smoothed the Transition to Marijuana Legalization in the United States. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13(1), 181-202. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110615-084851

Leafly.com. (2018). Explore marijuana strains and infused products. Retrieved 22/12/2015 from https://www.leafly.com/start-exploring.

Lee, M. (2012). Smoke Signals: A social history of marijuana-medical, recreational and scientific. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Lenson, D. (1999). On drugs. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Lopez-Quintero, C., de los Cobos, J., Hasin, D., Okuda, M., Wang, S., Grant, B., & Blanco, C. (2011). Probability and predictors of transition from first use to dependence on nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Drug and alcohol dependence, 115(1), 120-130.

Lopez, G. (2014). What if Big Marijuana becomes Big Tobacco?. Retrieved 02/05/2015 from VOX http://www.vox.com/2014/9/23/6218695/case-against-pot-legalization-big-marijuana. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6YXV8rehS). December 17

Maccallum, C., & Russo, E. (2018). Practical considerations in medical cannabis administration and dosing. European Journal of Internal Medicine, 49, 12-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2018.01.004

Maccarrone, M. (2005). Endocannabinoids and regulation of fertility Cannabinoids as Therapeutics (pp. 67-78): Springer.

Marijuana Policy Project. (2015). Marijuana Policy Project. Retrieved 09/05/2015 from http://www.mpp.org/. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6YXVfzbo4).

McLaren, J., Silins, E., Hutchinson, D., Mattick, R., & Hall, W. (2010). Assessing evidence for a causal link between cannabis and psychosis: a review of cohort studies. International Journal of Drug Policy, 21(1), 10-19.

Mechoulam, R. (2006). Cannabinoids as Therapeutics Milestones in Drug Therapy. Basel, Switzerland: Birkhäuser Basel.

Mechoulam, R., & Parker, L. (2013). The Endocannabinoid System and the Brain. Annual Review of Psychology, 64(1), 21-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143739

Meier, M., Schriber, R., Beardslee, J., Hanson, J., & Pardini, D. (2019). Associations between adolescent cannabis use frequency and adult brain structure: a prospective study of boys followed to adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, http://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.05.012

Merlin, M. (1973). Man and Marijuana: Some aspects of their ancient relationship. . New York, NY: A. S. Barnes and Company.

Mills, J. (2003). Cannabis Britannica: Empire, trade, and prohibition, 1800-1928. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Moreau, J. (1845/1973). Hashish and mental illness (H. Peter & GG Nahas, Eds., GJ Barnett, Trans.). New York, NY: Raven Press.

National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. (2017). The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: the current state of evidence and recommendations for research. US: National Academies Press.

Nestle, M. (2013). Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health. Berkerley: University of California Press.

NORML. (2017). NORML.org – Working to reform marijuana laws. Retrieved 09/05/2017 from http://norml.org/. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6YXW7zlIp).

Pacula, R., Kilmer, B., Wagenaar, A., Chaloupka, F., & Caulkins, J. (2014). Developing public health regulations for marijuana: Lessons from alcohol and tobacco. American Journal of Public Health, 104(6), 1021-1028. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301766

Proal, A., Fleming, J., Galvez-Buccollini, J., & DeLisi, L. (2014). A controlled family study of cannabis users with and without psychosis. Schizophrenia research, 152(1), 283-288.

Rolles, S. (2012). The Alternative World Drug Report: Counting the Costs of the War on Drugs. Retrieved 30/04/2015 from https://www.unodc.org/documents/ungass2016//Contributions/Civil/Count-the-Costs-Initiative/AWDR.pdf. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6Z3zGSBxI).

Room, R. (2012). Roadmaps to reforming the UN Drug Conventions. Retrieved 28/11/2017 from https://www.unodc.org/documents/ungass2016/Contributions/Civil/Beckley_Foundation/Roadmaps_to_Reform_Report_w_Foreword_110915.pdf.pdf. Beckley park, Oxford, UK: Beckley Foundation.

Room, R. (2014). Legalizing a market for cannabis for pleasure: Colorado, Washington, Uruguay and beyond. Addiction. 109(3), 345-351.

Room, R., Fischer, B., Hall, W., Lenton, S., & Reuter, P. (2010). Cannabis Policy: Moving beyond stalemate. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rosenthal, E. (2010). Marijuana Grower’s Handbook: Your complete guide for medical and personal marijuana cultivation Oakland, CA: Quick American Publishing.

Russo, E. (2016). Beyond Cannabis: Plants and the Endocannabinoid System. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 37(7), 594-605. http://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2016.04.005

Shulgin, A., & Shulgin, A. (1991). Pihkal: A chemical love story. Berkley, CA: Transform Press.

Smith, M. (2012). Heart of Dankness: Underground botanists, outlaw farmers, and the race for the cannabis cup. New York, NY: Broadway.

Solinas, M., Goldberg, S., & Piomelli, D. (2008). The endocannabinoid system in brain reward processes.Vol. 154, pp. 369-383 Oxford, UK.

Solomon, D. (1970). The Marijuana Papers: Panther Books.

Stoa, R. (2017). Marijuana Agriculture Law: Regulation at the Root of an Industry. Fla. L. Rev., 69, 297.

Strain Hunters. (2016). Strain Hunters Youtube Channel. Retrieved 7/3/2018 from https://www.youtube.com/user/strainhunters.

Subritzky, T., Pettigrew, S., & Lenton, S. (2016). Issues in the implementation and evolution of the commercial recreational cannabis market in Colorado. International Journal of Drug Policy, 27, 1-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.12.001

Theory of Knowledge. (2019). Key Ethics Ideas. Retrieved 16/9/2019 from https://www.theoryofknowledge.net/areas-of-knowledge/ethics/key-ethics-ideas/.

Thomas, B., & ElSohly, M. (2016). The Analytical Chemistry of Cannabis: Quality Assessment, Assurance, and Regulation of Medicinal Marijuana and Cannabinoid Preparations. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2016). World Drug Report. Retrieved 13/11/2017 from UNODC https://www.unodc.org/doc/wdr2016/WORLD_DRUG_REPORT_2016_web.pdf. New York:

Viveros, M., de Fonseca, F., Bermudez-Silva, F., & McPartland, J. (2008). Critical Role of the Endocannabinoid System in the Regulation of Food Intake and Energy Metabolism, with Phylogenetic, Developmental, and Pathophysiological Implications. Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders – Drug Targets(Formerly Current Drug Targets – Immune, Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders), 8(3), 220-230. http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/187153008785700082

Volkow, N., Baler, R., Compton, W., & Weiss, S. (2014). Adverse health effects of marijuana use. New England Journal of Medicine, 370(23), 2219-2227.

Wall Street Journal. (2014, Jan. 2). Colorado’s Pot Experiment. Retrieved 13/11/2017 from https://www.wsj.com/articles/colorado8217s-pot-experiment-1388707110.

Werner, C. (2011). Marijuana, Gateway to Health: How Cannabis Protects Us From Cancer and Alzheimer’s Disease. San Francisco, CA: Dachstar Press.

Its encouraging to see the re-emergence of plant teachers into public awareness and the possible acceptance of many different natural alternatives, as it was in ancient times.

It’s very clear that preventative health care should be skewed much more towards diet and natural supplements rather than external procedures and invasive operations. There is a great amount of ancient multicultural knowledge regarding various plants and foods and their various effects on the body. This earlier form of natural science needs to be reintegrated with our culture so we can reconnect to that basic physical wisdom generated from the interplay between our bodies and the biosphere around us.

During the process of conscious evolution we will come to realize that consciousness is not the same thing as the physical body, and yet the physical body is what provides us with the opportunity for conscious evolution in the first place. This potential for what is in the midst of what is not is not some kind of paradox but rather an entrance into the mysteries of life itself. In particular this sacred phenomenon is celebrated during the winter solstice holidays.