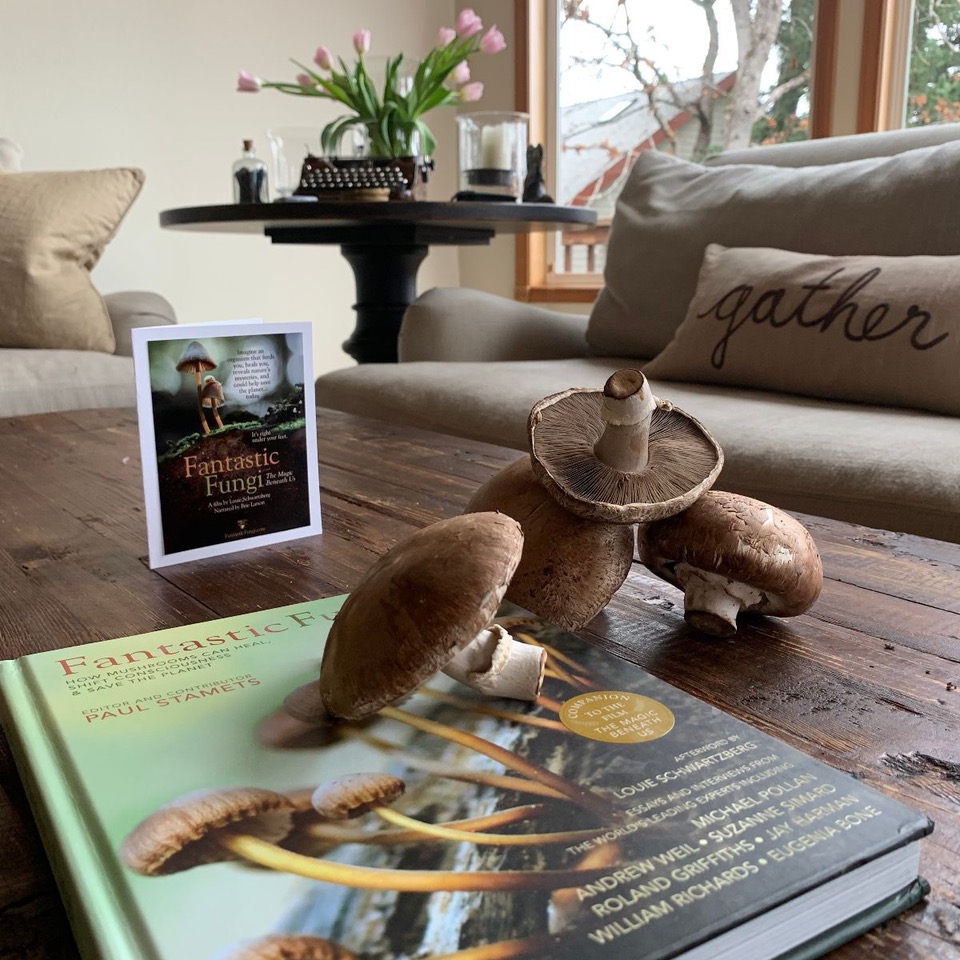

It is our pleasure to welcome Louie Schwartzberg, an award winning director, producer and author of the Fantastic Fungi film with a companion book edited by the preeminent mycologist Paul Stamets. Fantastic Fungi explores the beautifully complex world of mushrooms and their underground network of mycelium that weaves its magic web beneath our feet connecting plants and trees and supporting entire ecosystems. Fantastic Fungi draws our attention to immense importance of the role that mushrooms, and mycelium play in our global environment. It does this in a visually stunning and poetic way. It is a feast for the eyes and the imagination and points to hopeful future with mushrooms at the forefront of solving some of the planets most pressing problems.

“There’s a brilliant chemistry to mushrooms, and endless possibilities. We’re just at the beginning of understanding them.” —Michael Pollan

THE QUESTION UNDERNEATH THE QUESTION

by Louie Schwartzberg

The journey toward making the film Fantastic Fungi started almost thirteen years ago when I heard Paul Stamets give one of his first presentations at the Bioneers Conference. By that time, I had already been seduced by the sensual beauty of flowers and had been time-lapsing them twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, nonstop for over three decades. Part of that effort included time-lapsing mushrooms. After Paul’s presentation, I showed him some of the time-lapse videos of mushrooms I had on my laptop. In that moment, the mycelium network successfully made its intentional connection. That is what the mycelium network does: It connects living beings so life can flourish and so we can live in harmony with the Earth.

My passion for capturing imagery that inspires wonder and awe, and for capturing subjects that are too slow, too fast, too small, or too vast for the naked eye to see, is what led me to filmmaking. I love taking audiences through portals of time and scale. These immersive experiences are transcendent and broaden our worldview.

For a while, I thought that my obsession with capturing the beauty of a flower’s infinitesimal movement was enough of a reason for me to keep cameras filming around the clock. But then I learned about colony collapse disorder, the scientific name for the mass death of bee colonies, and I knew I could not tell the story of flowers without telling the story of the bees’ decline. Bees coevolved with flowers—a love affair that has been going on for over fifty million years—and we can’t let that relationship unravel. If the bees go, we go. All of the foods we need to stay healthy—including fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, berries, and some grains—come from pollinating plants. Without the evolution of the flower, warm-blooded mammals would never have evolved. Before the appearance of flowers, the Earth was a boring and drab place, mostly green. The cold-blooded herbivorous reptiles roaming the planet needed to eat huge quantities of leaves to stay alive.

So . . . I made a film about pollination called Wings of Life. It is a Disneynature feature film narrated by Meryl Streep, who acts as the voice of a flower who seduces bees, bats, butterflies, and hummingbirds. I learned through that filmmaking process that pollination is a keystone event, a magical intersection and interaction between the animal and plant kingdoms that happens billions of times each day. Without this event, life on Earth would be radically different.

I love exploring the big questions and diving into the mysteries of life. So, I thought, if plants are the only land-based life that can convert the sun’s energy into food, which is critical for our own and other creatures’ survival, what do plants need in order to survive? The answer is soil.

Now, let’s take it further. Where does soil come from? What can break down organic matter, including minerals from rock, to make soil? The answer surprised me. It is the largest organism on the planet, one that is everywhere, on every continent, under our feet, and inside our bodies: fungi! So, when I heard Paul’s presentation, I instantly knew that I was going to take a deep dive into the world of fungi and that I needed to make a film about this foundational aspect of life, which most of us know nothing about.

It has been a truly fantastic journey. Learning how mushrooms can feed us, heal us, clean up environmental pollution—including the atmosphere—and shift our consciousness has changed my life. I interviewed scientific experts, who shared their knowledge on all these topics, and featured those leading experts in the film in a format in which they could present those science-based facts to the general public.

Making the film was a great learning experience. Yet, it goes beyond education on some astounding levels. The beauty of the time-lapse mushrooms dancing as they emerge from their underground world both entertains and inspires. The journey through the underground mycelium network— which mirrors the networks of our own nervous and circulatory systems as well as of the internet and of galaxies in space—takes my breath away and has the power to bring audiences to tears of joy. I never knew that fungi, along with their plant partners, could be the greatest and fastest natural solution to climate change. The Mother Tree concept and underground internet idea—pioneered by Paul Stamets and Suzanne Simard—was the foundational science for concepts filmmaker James Cameron used in Avatar. Without that spiritual core, Avatar would never have become one of the top box office films of all time.

Yet, my biggest takeaway was learning that the mycelium network creates connections between plants and trees that enable ecosystems to flourish as symbiotic communities. Nothing lives alone in nature, and communities are more likely to survive than individuals. What a beautiful inspirational model for how human beings might live: In a shared economy based not on greed but on nurturing relationships and mutual cooperation.

One of the many wonderful aspects of making the Fantastic Fungi film was the collaboration between artists and scientists. There is an intrinsic relationship between science and art, and both foster an incredible sense of wonder. The underground mycelium sequences, which were animated by artists, used scanning electron microscopy images as references. The time-lapse sequences of growing mushrooms used the art of lighting and cinematography. And, bringing this arc full circle, I implored Paul Stamets, leading mycologist and brilliant inventor, to come up with a solution to save the bees. Paul embraced that challenge like a true Jedi Knight and developed mushroom extracts that have been proven in the field to save bees from the viral infections that are the major identified causes of their decline. That solution could save the world’s food supply.

We are now living in times of environmental breakdown and technological breakthroughs. We have barely scratched the surface of the fungal genome, which may prove to be one of our most important partners going forward. I am hopeful about the future, because answers to our greatest problems might be literally right under our feet. We need to open our eyes to nature’s intelligent design and our hearts to nature’s wonders. If we can embrace our fungal partners and ancestors, we can change the fate of our planet from mass extinctions to flourishing environments, and in so doing, foster communities—both for us and for future generations—that celebrate and honor life in its many forms.

MYCELIUM: THE SOURCE OF LIFE

The following is an excerpt from Chapter 1, written by Suzanne Simard, PhD, who is also interviewed in the film.

What goes on beneath a forest floor is just as interesting—and just as important—as what goes on above it. A vibrant network of nearly microscopic threads is recycling air, soil, and water in a continuous cycle of balance and replenishment. Survival depends not on the fittest, but on the collective.

Imagine a log that was once was a tree. Maybe it died of old age or became infected by a disease and fell over. When it did, fungi spread into the log from the earth below and started decomposing it. These fungi are part of a vast network of underground vegetation called mycelium, composed of very tiny, cobweb-like threads of organic life called hyphae. All along the thousands of miles of mycelium occupying this one big log, the mycelium uses the fungi to send out enzymes and organic acids that break down the lignin in the wood’s cell walls that gives the wood its structure and strength.

In the process of decaying, the wood releases its nutrients. Those nutrients become available to other organisms in the food web, including the fungus, which distributes the nutrients through the mycelium. After many challenges, these networks come to the surface and form mushrooms, the reproductive structures of fungi. Mushrooms are literally “the tip of the iceberg.” When we see mushrooms, there’s actually a vast network of mycelium hidden in the ground beneath them. Only about 10 percent of all fungi produce mushrooms. But when you pick a mushroom, you stand upon a vast, hidden network of fungal mycelium that literally extends underneath every footstep you take. These networks are the foundation of life. They create the soils that nourish all life on land. Without fungi, we do not have soil. Without soil, there is no life.

Without this metamorphic process, the planet would choke. Forests would be miles deep in organic decay. The only reason we can walk around in most woods is because thousands of species of fungi are decaying all of the organic detritus on the forest floor, recycling the dead material and beginning the renewal of life.

Once the log starts to decay and release nutrients, other organisms such as mites and nematodes move in and start eating the fungus, small bits of leftover wood, and other organic material, which they ultimately excrete. Some of that ends up in the nutrient cycle, and then other critters like spring- tails or spiders come along and eat the nematodes, and then other creatures eat the springtails and spiders, and so it goes up the food chain to larger and larger organisms. Even mushrooms become food for squirrels, and eventually something will eat the squirrel—maybe a bird, maybe a bear—and it’s all linked back to that original wood-decomposing fungus. When each organism reaches the end of its life, it returns to the soil and continues replenishing the cycle.

In all ecosystems, death and decay are the fundamental beginning of life. If a forest never went through this process, it couldn’t regenerate. It would crowd near big trees, leaving few gaps for young ones. The big trees would suck up the light, water, and nutrients. Decay organisms like fungi are crucial for that process of regeneration. They are the building blocks of the ecosystem, the fundamental starting place for how a forest grows.

MOTHER TREES AND THEIR FUNGAL PARTNERS

Forests are incredibly complex places with trees of many different sizes and compositions, depending on the type of forest. There are little trees coming up in the understory, and then there are the parents, the big trees that provide the seeds for the forest’s continued diversity and generational health. We call the biggest and the oldest of these trees Mother Trees because they are connected below ground to all the other trees around them—their community—by what we call a mycorrhizal fungus.

A mycorrhizal fungus is a special kind of organism that forms a symbiotic relationship with the tree. It wraps its fungal body around soil particles, extracting nutrients and water that it then brings to the roots of the tree. In return for this precious nourishment, the tree obliges the fungus by providing it with the sugars that the fungus needs to survive. These sugars are infused with carbon that the tree has accumulated through photosynthesis.

Climate change is the result of an accumulation of greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere, and carbon dioxide (CO2) is the biggest culprit. Carbon dioxide is also what plants photosynthesize. They put that carbon in different places, such as their leaves and trunks, but we now know that 70 percent or more of that carbon actually ends up below ground.1 It’s first stored in the cell walls of plants until it’s traded for nutrients via these root exchanges with mycorrhizal fungi. Once the carbon has been absorbed by these fungi, it can stay underground for thousands of years. And surprisingly, when mycelium dies, it also locks in the carbon for extended periods of time, building a carbon reserve for the future.

These mycorrhizal fungi form a network of threads that bond with the roots of other trees in the neighborhood and connect them all, no matter the species, like underground telephone wires. The biggest and oldest trees—the Mother Trees—have the largest root systems and the most root tips intertwined with these fungi, and they therefore connect with more trees.

We often think of kin selection or kin recognition as an animal behavior, but our research is showing that these Mother Trees also recognize their own kin—their seedling offspring—through these mycorrhizal networks and communicate with each other through carbon.2 Carbon is their universal language. The stronger trees support the weaker ones by regulating the flow of carbon between them. If a Mother Tree knows there are pests around and her offspring is in danger, she’ll increase their competitive environment. A good example is the Leucaena leucocephala (commonly known as the white leaf tree or river tamarind, among other names) that is native to southern Mexico and northern Central America. When it senses a competing species, it releases a chemical into the soil that stops the competitor’s growth. It’s a magical thing and it could not happen without the fungi.

Scientists have been obsessed with competition and the survival of the fittest ever since Charles Darwin posited the theory of natural selection. In a lot of ways, our innate competitive instincts influence how we view each other and manage the natural world around us. We tend to favor those individuals who are big and strong and best positioned to win. We do this in forestry, in agriculture, and in fisheries. And yet the way people behave and thrive depends on a community. It’s no different in the forest. The cooperation that goes on between trees and plants is just as important as the competition, which allows them to work together to adjust to changes and threats in their environment.

We’ve always thought of plants and trees and fungi as essentially inert objects that don’t interact with each other, that don’t build things. But my work and others’ is showing that they need each other to share the load and grow as one: You do this, I’ll do that, and together we will thrive. This gives me incredible hope. Nature wants to heal itself; even if you try to make a bare space, plants will fill it in. They want to be there. They just show up and start doing their thing. So, by maintaining and protecting the plants, the forests, and the fungal networks, we will help to support a beautiful, resilient community that is also a natural engine for restoring and maintaining a sustainable planet.

NOTES

- T. A. Ontl and L. A. Schulte, “Soil Carbon Storage,” Nature Education Knowledge 3, no. 10 (2012): 35, https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/soil-carbon-storage-84223790.

- Monika A. Gorzelak, Amanda K. Asay, Brian J. Pickles, and Suzanne W. Simard. “Inter-Plant Communication through Mycorrhizal Networks Mediates Complex Adaptive Behaviour in Plant Communities,” AoB PLANTS 7, no. 1 (January 2015), https://academic.oup.com/aobpla/article/doi/10.1093/aobpla/plv050/201398.

Book available for purchase: https://fantasticfungi.com/book/

Reviews for the film, the companion to the book:

“A must see for anyone interested in life, death and the pursuit of the planet’s well-being.”

~ David Carpenter, Forbes

“Schwartzberg’s film quickly proves to be one of the year’s most mind-blowing, soul-cleansing and yes, immensely entertaining triumphs.”

~ Matt Fagerholm, RogerEbert.com

“Gorgeous photography! Time-lapse sequences of mushrooms blossoming forth could pass for studies of exotic flowers growing on another planet.”

~ Joe Morgenstern, The Wall Street Journal

“Louie Schwartzberg’s … delightfully kooky documentary, ‘Fantastic Fungi,’ offers nothing less than a model for planetary survival.”

~ Jeannette Catsoulis, The New York Times

“As researchers describe the workings of vast underground networks of mycelium, the filmmakers offer CG that is just as polished as the time-lapse, and more colorful. It’s spookily beautiful, even, especially when envisioning what lies unseen beneath old-growth forests.”

~ John Defore, The Hollywood Reporter

“Mushrooms are the new superheroes, as Brie Larson dreamily narrates over what is not a new Marvel epic but rather a documentary of epic proportions.”

~ Robert Abele, The Los Angeles Times

“Fascinating, informative, educational and totally entertaining.”

~ Rex Reed, The Observer

One of only nine films to receive 100% Rotten Tomatoes in 2019.

It all depends on what type of forest and environment. For example Australian aboriginal people burnt forests down in order to maintain fires…which is why one of the reasons the Australian bush fires are out of control. Nature is a cruel beast towards itself the way beings go about deceiving each other in order to obtain meal…I’m sure this great consciousness everyone goes on about could have come up with better way in order to get energy instead of the cruel way nature goes about treating itself like just some meat grinding recycling robot. You look at animals no remorse at the way they kill things..just like a robot terminator no emotions remorse for there killing…

Enjoyed looking through this, very good stuff, thanks. “It is well to remember that the entire universe, with one trifling exception, is composed of others.” by John Andrew Holmes.

Darwin talked about “survival of the fittest,” and Dawkins talked about “the selfish gene,” but it seems like Suzanne Simard is saying, “Wait a minute.”

We’re more and more comfortable with complex systems these days, and complex systems go far beyond primitive control systems based on chance. Fungi seem to provide communication that can be used to thwart a bully or repair damage. She’s well on her way to a new evolution where wisdom within complex systems can exert control for the collective good.

We just saw this film and it was absolutely incredible and we will never look at mushrooms on the same way! From saving the environment through all the networks the for and the carbon consumption to the medicinal application, fungi is vital to our existence. What an education – we highly recommend!