Dedicated to Sister Viktorine Zak

Disclaimer: I’m not a licensed medical practitioner, and I can’t give medical advice. None of the below should be considered anything more than the opinions of a highly opinionated dilettante suffering from at least one mental disorder.

If you make choices regarding your health based on something you read on the internet written by someone who thinks the end is nigh, ADHD is the least of your problems.

Boring Dullness Hypertolerance Disorder (BDHD)

I only realised it was #ADHDAwareness month after the month had passed (maybe I was distracted or hashtags are boring or something).

Someone on LinkedIn was describing how reassuring it was to learn that they had ADHD. I’ve heard similar from others discovering that there is a name for their torment and I’m sympathetic: a diagnosis is a gnosis after all, a “knowing”, and there is solace in knowing that you are something that can be categorised. As the post put it, “it’s better to be a zebra than a weird horse”. But a zebra is a lovely thing, so much so that its collective noun is “dazzle”. I’d like to be in a dazzle of zebras. Being called “deficient”, “hyperactive” and “disorderly” is less flattering, and I don’t think there is a collective noun for people with ADHD.

A convention?

A software company?

A Dazzle, by Paul Maritz (CCBYSA3.0)

Oppressed groups have successfully reclaimed offensive labels such as “queer”, but calling ourselves ADHD feels like something different. Adopting this language feels like allowing psychiatrists to pathologize us, and even those who are sympathetic to our plight fall into the trap. For example, while I appreciate Gabor Mate’s kindness, his idea that ADHD is just a trauma response only tells half the story. There is a highly heritable (80%) cognitive style that, when subjected to the stresses of the 21st century, often leads to a set of symptoms, but that isn’t a simple causal relationship. By comparison, I get sunburned easily in Brazil and so does my father, but my half-black kids don’t; the “disorder” of sunburn is a combination of our genetics and an environmental condition. If we were measuring Vitamin D deficiency in Northern Europe rather, their disorder would be graver than mine.

The diagnostic category of ADHD is good for the pharmaceuticals industry, certainly, with the global market for ADHD medication projected to reach nearly $25 billion by 2025, but is it good for us to adopt a label which is not only insulting but inaccurate? My attention is in abundance, not deficit, if the material I’m attending to is interesting. If I find you boring, that might say more about your deficiencies than mine. Perhaps you have BDHD?

Along with measured benefits including higher energy, an appetite for adventure, more courage, integrity and resilience and better self-awareness, those of us with (the cognitive style AKA) ADHD don’t create or apply categories as readily as the people categorised as neurotypicals (NTs – which I pronounce “nautists”). “Autistic spectrum disorder” (ASD), “attention deficit hyperactive disorder”, “dyslexia”, “obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)” and so on can be helpful markers, but the labels are unhelpful if we confuse them with reality. So, rather than trying to parse this pudding, I’m going to consider the wider topic of neurodiversity. 50-70% of individuals classified as having ASD also present with ADHD anyway, and these conditions share not only traits but also structural markers in the brain. We also share jail cells. An estimated 3-4% of the UK population is thought to have ADHD, whereas in prison it is 25%, and while 1 in 10 people in the UK are dyslexic, in prison it is 50%.

Many scientists seek to explain the causes of ADHD, but the question I want to address here is different. I’m interested in how we survive under conditions of psychological apartheid.

For one thing, it seems that we club together and even form new clubs – so some people have begun to self-identify as AuDHD (Autistic and ADHD). This is not surprising, as neologism (coining new terms) is one of the ways that the neurodivergent are more creative than nautists. But maybe we can think of better words for ourselves than “deficient”. How about Asper(ger)ational? Or awetistic.

Artwork by Ambigraph, with permission

Why you can’t treat ADHD

People have been asking me about ADHD recently – perhaps because I’m vocal and positive about my own neurodivergence. I’m also sceptical about how our culture denigrates non-normative experiences (from voice-hearing to psychedelic-induced) and I’m interested in how traditional medicines perform compared to neat white pills. I’ll be surveying research into both modalities below, as well as looking at how society defines norms and pathologizes the abnormal, and asking questions about how we make decisions on matters as important to us as what is happening inside our heads.

But let’s not sugarcoat this pill. While the diagnostic category is disempowering, (the cognitive style AKA) ADHD can be exasperating. Forgetting why you have gone upstairs three times in a row is boring, and it can be uncomfortable for everyone concerned when you won’t join in with small talk about the Royal Family or Arsenal, or can’t turn off your empathy or passion, or sit quietly when someone does something that makes your brain itch, or just sit quietly. I manage well enough when I’m managing but at the moment I’m not. I’m rewriting this article because I erased weeks of work by hitting save on a previous version that was hiding amongst a… frazzle (?) of unnoticed tabs. I also have a rat infestation, despite the fact that I seem to be clearing up after myself constantly, and one of them chewed through the washing machine pipe, so I’m also rewriting in a flooded room. I can hear them squeaking at me mockingly and I’m terrified I’m about to be ejected from my home for the third time in as many years.

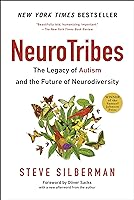

As a former schoolteacher, I can also confirm that while I don’t agree with how hyperactive kids are conventionally managed, they can ruin a classroom when their disruptive traits aren’t managed. But creativity and disruption are two sides of the same coin, and keeping the coin spinning is a lifelong struggle for people like me. The history of technology, art and science shows, however, that this struggle drives a great deal of innovation and also generates rewards for nautists. Neuro Tribes is a good history of this.

Personally, I’ve learned to enjoy how my brain works, and that necessitates accepting the tails side of the coin. I know (because I keep getting told) that I am a challenging person to be with – but that is everyone else’s problem as much as it is mine. Sometimes I challenge people into thinking differently.

That includes clients who come to me for hypnotherapy (see: https://pattern-interrupt.co.uk/) asking if I can treat ADHD. I can no more treat ADHD than I can treat tallness. I can help tall people remember to duck when they go through doorways, and I can help people manage the downsides of (the cognitive style AKA) ADHD, because I’m a very good hypnotherapist. But I can’t fix something that isn’t broken.

Artwork by Gonchir, with permission

So let’s think a little differently

A friend who felt he had benefited from methylphenidate (Ritalin) recommended it to me the last time I was struggling with my own cognition, around the same time that a teenager I’m rather fond of was medicated by parents who are well-meaning but ill-informed, so I did some research. We’ll start by exploring psychiatric treatment and then come back to other ways of thinking about the condition. I hope you’ll forgive the massive info dump – I found the whole area fascinating. You can blame it on my ADHD, and if you skip some of it I’ll blame it on yours.

Artwork by Gonchir, with permission

Diagnosing divergence

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is the text psychiatrists use to categorise humans in a way that satisfies American healthcare insurance providers that their feelings or behaviour constitute a disease covered by their insurance plan. The first edition was published by the US Army in 1952, the year that the American Federal Security Agency proposed expanding health insurance as a step towards compulsory universal coverage. 1952 was also two years into the Korean War, and the foreword of DSM-1 notes how war leads to “an increasing psychiatric case load” of soldiers without obvious physical injuries who require treatment (and therefore insurance payouts, and therefore defined mental disorders). It is currently in its fifth edition (DSM-5). To a hammer, everything looks like a nail; to DSM-5, my cognitive style is a disorder.

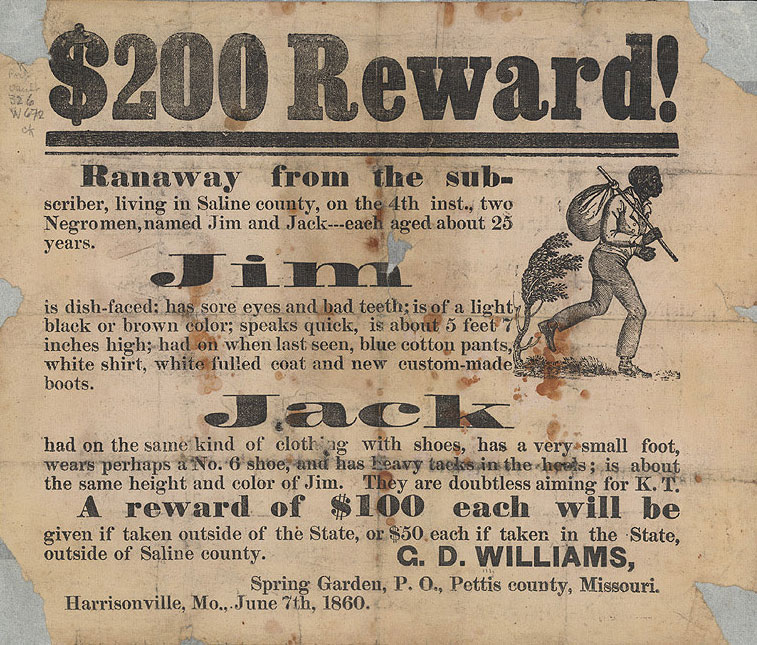

Homosexuality was classed as a disorder in DSM-1, along with “pedophilia, fetishism and sexual sadism (including rape, sexual assault, mutilation)”; the recommended treatment was electric shocks. Psychiatry has a long history of using Greek and Latin to classify deviance. Slaves with poor motivation were said to be afflicted with “dysaesthesia aethiopica” (literally bad black/Ethiopian feeling) and those so disorderly as to keep slipping their chains and running away were suffering from “drapetomania”. Once the category is applied, remedial measures become justified. The former was cured with the whip, the latter by amputating the big toes.

DYSAETHESIA AETHIOPICA… CALLED BY OVERSEERS, “RASCALITY.”

There is a partial insensibility of the skin, and so great a hebetude of the intellectual faculties, as to be like a person half asleep, that is with difficulty aroused and kept awake… it is accompanied with physical signs or lesions of the body discoverable to the medical observer… It is much more prevalent among free negroes living in clusters by themselves, than among slaves on our plantations, and attacks only such slaves as live like free negroes in regard to diet, drinks, exercise, etc.

DRAPETOMANIA, OR THE DISEASE CAUSING NEGROES TO RUN AWAY

“The cause in the most of cases, that induces the negro to run away from service, is as much a disease of the mind as any other species of mental alienation, and much more curable, as a general rule. With the advantages of proper medical advice, strictly followed, this troublesome practice that many negroes have of running away, can be almost entirely prevented, although the slaves be located on the borders of a free state, within a stone’s throw of the abolitionists.”

From Report on the diseases and physical peculiarities of the Negro race – Samuel A. Cartwright (1851)

$200 Reward! for runaway slaves, June 7, 1860 (PD0)

It is easy to demonise those who administered the treatments, but perhaps more charitable to consider how slave owners (along with parents of queers, physicians of fetishists and husbands of nymphomaniacs) were trying to keep their charges safe from harmful influences according to the mores of their time. Reserving judgment also frees us up to think about how those mores came to be, and about our current societal norms.

It would also be easy to think we are more enlightened these days. The third edition of Stedman’s Practical Medical Dictionary, published in 1914, was the last to list drapetomania, and homosexuality was dropped from the revised edition of DSM-3 in 1987. This was around the time that a well-meaning and ill-informed teacher called Mrs. B suggested that Ritalin might be beneficial for 11-year-old me. I have no intention of demonising Mrs. B, nor any teacher or parent trying to negotiate the gears of a machine without letting a child be mangled by the cogs. My intention here is to understand the workings of the machine.

Having given some context to the nature of the psychiatric gaze, let’s consult DSM-5 on the typical ADHDer:

-

Displays poor listening skills

-

Loses and/or misplaces items needed to complete activities or tasks

-

Sidetracked by external or unimportant stimuli

-

Forgets daily activities

-

Diminished attention span

-

Lacks ability to complete schoolwork and other assignments or to follow instructions

-

Avoids or is disinclined to begin homework or activities requiring concentration

-

Fails to focus on details and/or makes thoughtless mistakes in schoolwork or assignments

I’m not denying that this is a painfully accurate description of some aspects of my mind in some circumstances. I’m just saying what I said to Mrs. B: no thanks.

Artwork by Aïda Gershwin, with permission

How does Ritalin treat ADHD?

The pathways of (the cognitive style AKA) ADHD are myriad, and imaging studies of the most complex object in the known universe can only tell us so much. The evidence most relevant to the pharmacological gaze pinpoints decreased levels of dopamine in the striatum (which is involved in planning, motivation and making decisions). Most ADHD medications increase the amount of dopamine available. I’ll be focusing on Ritalin, which does this by inhibiting the transporter that clears dopamine away from the synapse (and tends to be grape or cherry flavoured). Amphetamines such as Adzenys (orange favoured), Dyanavel (bubblegum flavoured), Vyvanse (strawberry flavoured) and plain old Adderall are arguably worse.

How well does Ritalin treat ADHD?

Poor quality of the evidence

It is difficult to say much with confidence as the research is of such poor quality.

The Cochrane Review (2023) concluded that 191 of the 212 trials surveyed were “at high risk of bias”, and that evidence for many of the therapeutic effects claimed was of “very low-certainty”. Though the NHS advises that “you may need to take methylphenidate for several months or even years”, the science has nothing to say regarding long-term (or even mid-term) use. This is because “there have been no clinical trials to evaluate the effectiveness of Ritalin for more than 4 weeks of treatment”.

Enlightened parents this side of the Enlightenment tend to defer to the science, so this is what I have to work with; I’ve focused on meta-analyses and large samples, and done my best to keep my sarcasm in check. Keen researchers will find studies presenting opposite conclusions, but take note of the funder: firstly, research funded by the pharmaceutical industry is “four times more likely to find positive results than research backed by other sponsors”; secondly, psychiatry journals are less likely to publish negative research; and, thirdly, “[w]ithholding the publication of unfavorable results… is not uncommon”.

Having added paranoia to my own list of symptoms, let’s see what this “the science” has to say.

Artwork by Gonchir, with permission

Poor performance of Ritalin

Regarding quality of life, the largest meta-study found that it “may improve teacher‐rated ADHD symptoms and general behaviour in children and adolescents with ADHD. There may be no effects on serious adverse events and quality of life [italics mine].” A 2021 meta-analysis of 24 systematic reviews described evidence of the drug reducing symptoms as “of very low certainty”.

Data on academic performance are similarly unimpressive. A 2021 systematic review of 12,269 subjects found no evidence of benefits in academic improvement; indeed, there is some evidence pointing in the opposite direction. A study of 40 healthy participants found that the drug made them approach a cognitive task with more motivation but they took around 50% longer to complete it, and their accuracy dropped.

The 2021 review also found significant “underreporting of adverse events”, and that “none of the included reviews of good quality from our search mentioned the effects of withdrawal symptoms”. This is a glaring omission, revealing that “the science” is not only careless but heartless. Speaking from experience, being a neurodivergent 14-year-old is tough enough without having to deal with drug withdrawal.

In the absence of any decent studies, we must do what we did for millennia and rely on the observations of herbalists. My favourite practitioners are the Seed Sistas, who describe symptoms of withdrawal including sleep disruption, anxiety, restlessness and digestive problems. At the interface of teenage peer pressure and multi-million-pound campaigns from Satan’s own marketing agency, the potential for replacing grape-flavoured dopamine-boosting stimulant tablets with grape-flavoured dopamine-boosting stimulant vapes should be taken seriously.

Ritalin vs. placebo

Parking for a moment the objection that symptoms include not obediently doing things a child finds boring, a meta-analysis of 94 studies and 6,614 patients found that placebo sugar pills are responsible for “a 23.1% reduction in the severity of ADHD symptoms”. This is close to the 25% considered clinically relevant, but things get really interesting when you look closely at what is being measured. For example, a study (on Atomoxetine) found that placebo was almost as good as the drug at reducing irritability and arguing in the morning, but in the evening the drug far outperformed it.

What is significant here, doctor – that kids become more tetchy when tired? That’s obvious to anyone who knows a child, and it’s obvious that stimulants will reduce it too – but so would more sleep, better screen hygiene, more attentive parenting perhaps… Another factor is that it is often the parents who assess their children on highly subjective parameters. We might equally conclude that parents are more irritable when they are tired, more likely to get into fights with their kids, and more likely to blame them for it. Most studies reporting that symptoms “improve” fail to indicate which symptoms, which makes them all suspect if you take issue with the idea that being obedient and uncritically tolerating boring tasks is a good thing.

The meta-study also noted that “placebo response in ADHD increased by 63% between 2001 and 2020”, which is to say that things are improving for sugar pill-swallowing youths with ADHD diagnoses. Similar trends have also been noted for mania and psychosis. This is the exact opposite of what is observed with psychiatric medicine, at least in trials for depression; drugs have become less effective over time as the hype for new ideas fades and the marketing machine moves on to something else.

The power of placebo is curious, to say the least, active even in an open-label trial where children were told they were taking a placebo rather than a drug. This isn’t the place to take a wrecking ball to the whole edifice of science (my book Science Revealed does that). But it does seem rather boring and conservative – one might even say nautistic – to look at data that reveals something extraordinary about the weird and wonderful nature of our body-minds and conclude that our kids are best served by putting stimulants in their Wheetos.

Highs and lows of Ritalin

Ritalin was named after its inventor’s wife Rita, who was pleasantly surprised by its effect on her tennis game (because it’s a stimulant and it does what it says on the tin). Like other stimulants, the potential for abuse is high because larger doses than prescribed produce euphoria, and the kids are well aware of that; one study found that “16% of the children had been approached to sell, give, or trade their medication.”

Apparently, Ritalin also makes you feel good at normal doses (though I wouldn’t know as I don’t take it). Coffee certainly does (while messing with my sleep and digestion and helping me talk nonsense). In defence of coffee, my favourite herbalists administer it to help with Ritalin withdrawal, and another friend uses it to focus the mind of her highly neurodivergent son. We wouldn’t expect a paediatrician to recommend it, however. As the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry puts it, “there is no proven safe dose of caffeine for children”. There’s no proven safe dose for Ritalin either, and yet the American Academy of Pedriatrics recommends it for children as young as four.

The drug’s reputation has completely flipped since 1971, when doctors raised concerns about Ritalin to the US Senate and described it as the no. 1 drug abuse problem in Seattle. There may have been good reason, because the flip side to stimulants can be brutal. With Ritalin, there is a “temporal relationship between depression and methylphenidate use in young people with ADHD”.

Parents should have the right to give their kids coffee and wine, ice cream and iPhones, to cut their hair, pierce their ears, to vaccinate them or not, to educate them at home or to send them to Sunday school, to give them high heels regardless of the effects on a developing spine and Ritalin regardless of its effects on a developing brain – basically to do whatever they feel is best regardless of other people’s opinions. This is deeply problematic, of course, but not as problematic as allowing politicians to make and enforce those choices. “Drug abuse” is in the eye of the beholder and I don’t have a problem with it, at least, nothing I can’t handle. I have a problem with state-sanctioned hypocrisy and incoherent thinking that actively promotes chemically modifying the behaviour of children via means that may cause brain damage (I mean this literally, as we will see below).

Side effects of Ritalin

Novartis, the manufacturer of Ritalin, notes that “common” side effects include

“nervousness, insomnia… anxiety, restlessness, sleep disorder, agitation, depression, aggression,… dyskinesia, tremor, headache, drowsiness, dizziness… tachycardia [elevated heart beat], palpitation, arrhythmias [irregular heart beat], changes in blood pressure and heart rate,… nausea… abdominal pain, vomiting, dyspepsia [indigestion], toothache… rash, pruritus, urticaria, fever, scalp hair loss, hyperhidrosis… arthralgia [joint pain]… Raynaud’s phenomenon”

Meta-analysis with sample sizes of over 10,000 reported that:

[T]the proportion of participants on methylphenidate with any non‐serious adverse events was 51.2%… These included difficulty falling asleep, 17.9%… headache, 14.4%… abdominal pain, 10.7%… and decreased appetite, 31.1%.

A small study found that 3.6% of subjects had side effects serious enough to warrant “immediate discontinuation of medication”. Even so-called “non-serious side effects” may have profound impacts. Decreased appetite, for example, is considered “non-serious”, but could it partly explain why Ritalin is stunting children’s growth by “approximately 1cm/year during the first 1-3 years of treatment”?

What else is not developing normally?

The Lancet reports that reduced nutritional content in adolescents affects not just musculoskeletal growth but also cardiorespiratory fitness, immunity and the development of the brain. In normal brain development, there is a period of remodelling that peaks from 13-15, which are also peak Ritalin years. The frontal lobes continue maturing until the mid-twenties and are involved in inhibiting urges and moderating instincts such as risk-taking behaviours and the sex drive. Could developmental stunting of inhibitory systems explain why Ritalin has caused spontaneous ejaculation, hypersexualism, and “prolonged and painful erections, sometimes requiring surgical intervention”?

Was that grape or cherry flavour?

Brain damage

In people without ADHD, Ritalin was found to cause:

“changes in brain chemistry [that] were associated with serious concerns such as risk-taking behaviors, disruptions in the sleep/wake cycle and problematic weight loss”

Another study concluded that “chronic Ritalin intake may result in permanent brain damage if prescribed in childhood”.

One pathway has been established in rats given Ritalin: oxidative stress. High dopamine levels cause oxidative stress and this kills brain cells, contributing to various diseases including Parkinson’s. And sure enough, people with ADHD diagnoses are more likely to develop Parkinson’s and other degenerative brain diseases. The jury is still out on whether the Parkinson’s is caused by the medication or something native to ADHD brains, but it’s a relatively new drug with poorly understood pathways that kill brain cells. I wouldn’t trust that jury with my brain!

Does it help, and whom does it help?

Speaking generally (ie. rigidly applying a loose category to make my point in an almost nautistic fashion and ignoring the fact that I do know a psychiatrist who isn’t a nutjob): if psychiatrists cared about what their prescriptions do to brains, they would follow the research, but the trend is going in the opposite direction. Polypharmacy, for example, is the use of several drugs together, and it can cause all kinds of eventualities in a complex system. Despite extremely scant research, polypharmacy prescriptions have trebled over the last 20 years, particularly for ADHD. “More than 80% of US youths with reported psychotropic polypharmacy had an ADHD diagnosis”. Certainly, this helps drug manufacturers. But does it help you?

Summing up so far: working from assessments that are often made by teachers and parents rather than the kids on drugs themselves, Ritalin seems to work fairly well if the goal is to make children obedient. There is no good evidence, however, that it makes them happier, and nor does it seem to improve academic performance – it may in fact impair cognitive skills. As well as bringing kids into contact with drug trafficking, it has a long list of adverse effects: it causes depression, stunts growth, subjects the brain to oxidative stress and likely contributes to degenerative brain damage. And “the science” doesn’t care enough about children’s mental health to study the effects of taking it for more than four weeks, nor to measure withdrawal symptoms.

Your experience may tell you that Ritalin makes your life better, and it is important to take your experience seriously. Firstly, it might be an idea to reflect on how it makes life better. For example, it might make monotonous tasks easier to complete, and you may be obliged to perform monotonous tasks. In this case, one might say that Ritalin helps you cope with your subjugation and wage slavery, much as gin helped poor Londoners cope with theirs in the 1700s. Or perhaps it makes you better at remembering things, in which case are there other times when your memory works better? – when you’re on holiday, for example, or getting plenty of sleep, or not exhausted from constantly modifying your language and behaviour to conform to norms that make you abnormal?

Secondly, we make better experience-based decisions when our experience is broad – so how broad is yours? Once you have spent a few weeks experimenting with the herbal medicines and techniques described below, you will be in a position to judge from your experience which serves you better, and whether the collateral damage that Ritalin does is worth the reward.

My own experience is that herbal medicine helps me out, and scientific evidence would seem to support that conjecture.

Artwork by Aïda Gershwin, with permission

Traditional medicine

Doctors distinguish between “mainstream/modern/conventional” medicine and “alternative/complementary” medicine, which is an example of how modernity selects norms and then privileges systems that preserve them while accumulating wealth and centralising power in corporate offices and government bureaus. A better distinction might be made between complex or simple medicines. Traditional medicines are biochemically complex, which makes their effects on a biochemically complex system like a person impossible to understand from within a simple pharmacological model where “this molecule does this thing to this receptor”. This is a limitation, not of herbalism but of “the science” and of those institutions that prefer terms like “dopamine-reuptake” to “vata-reducing”.

This chauvinism also means that one of the major advantages of herbalism is overlooked and excluded, because while conventional medicines are usually single-molecule preparations, plants prescribed by herbalists are not – they often contain both compounds that produce the desired effects and also other compounds that protect the body from adverse effects. Any dopamine-boosting chemicals, including those in traditional medicines, will cause oxidative stress (as that is what increased dopamine does), and that will kill neurons and degenerate the brain. Unlike Ritalin, Adderall and the like, however, the herbal medicines listed below are also neuroprotective. Specifically, they contain antioxidants that prevent cell damage by free radicals.

While I don’t take pharmaceuticals, I do rev up my dopamine system, and my attention (far from being in deficit) gets so point-focused that I sacrifice sleep and forget basic self-care. As I enter my umpteenth late night in front of my computer, mainlining sci-hub and whiskey, I am pleased to reflect on how all of the medicines listed below reduce the damage done by increased dopamine – including that caused by the dopamine-hit chasing behaviours that people like me are prone to.

Ginkgo biloba

Gingko increases dopamine levels and is neuroprotective via various pathways, including as an antioxidant (helping against oxidative stress). It improves cognitive function and ADHD symptoms, but – in contrast to Ritalin – subjects also reported improved quality of life and mental health.

Gingko also has potent effects against anxiety, which is significant as, simply put, anxiety makes you stupid. Mildly anxiety-inducing images reduce scores in problem-solving tasks by half, and a person’s IQ drops by 13 points on average if measured when they are facing financial stress. My personal experience is that the negative sides of my cognition get much worse when I’m stressed out with application forms and calendars, and it can happen quite suddenly – I’ll be spinning 15 plates quite happily but if someone hands me a 16th I might drop them all and stop sleeping.

Rather than looking at this interaction, most of “the science” seems to be more concerned with measuring how the disorder of Generalised Anxiety overlaps with the disorder of ADHD, and medicating comorbidity more thoroughly. In any case, Gingko treats both at the same time. In fact, it was found to outperform suriclone and lorazepam in treating anxiety, and the effect was still increasing after four weeks while the effect of pharmaceuticals and the placebo had levelled out.

Ginkgo seeds by Harlaching (CCBYSA4.0)

Frankincense

Frankincense is also neuroprotective, and works via ion channels to make dopamine receptors more responsive. I’ve discussed its psychopharmacology in a peer-reviewed article called Getting High with the Most High in the Journal of Psychedelic Studies and Drugs, the Israelites and the Emergence of Patriarchy on Lucid News.

Frankincense by Gaius Cornelius (PD0)

Bacopa monnieri (Brahmi)

In Ayurveda, Bacopa monnieri is called Brahmi after Brahma, the creator of the universe, recalling its qualities of promoting creativity, calm and mental focus. It modulates dopamine, serotonin, GABA and acetylcholine, improving mood, memory and cognition. As well as making people cleverer (perhaps because they get less flustered when doing tests), this makes it useful in managing the more complicated aspects of (the cognitive style AKA) ADHD:

“Symptom scores for restlessness were reduced in 93% of children, whereas improvement in self-control was observed in 89% of the children. The attention-deficit symptoms were reduced in 85% of children.”

Given that Brahmi also treats hormonal imbalance, stress and anxiety, epilepsy, bipolar disorder, allergies, digestive issues and more, perhaps this brain tonic, rather than Ritalin, should be pushed onto schoolchildren. It certainly wouldn’t hurt – indeed, it is helpfully neuroprotective, containing antioxidants and mitigating Parkinson’s, meaning that you could take it along with Ritalin to reduce the damage.

Bacopa monnieri, by Forest & Kim Starr (CCBYSA3.0)

Celastrus paniculatus (the Intellect Tree)

I recently met Acacea Lewis, a brilliant young autistic ethnobotanist who introduced me to another Ayurvedic medicine she prefers to Brahmi (traditionally the two are often combined). Celastrus, also called the Intellect Tree and Jyotishmati (meaning “lustrous”) is another dopamine booster with antidepressant action and neuroprotective effects against oxidative stress.

“These results suggest that C. Paniculatus might be useful in relieving anxiety, hyperactivity, reward-motivated behaviour and ameliorating the symptoms of ADHD by alternating neurotransmitter levels”

My dose is eight seeds whenever I remember to take it, and, subjectively speaking, I think it is wonderful. While it is difficult to distinguish between the effects of Celastrus and Bacopa (because I usually take whatever jar I come across first as I stumble around the chaos of my living arrangements), I’ve generally been both creative and calm despite recent stresses. The effect will, I believe, be more long-lasting and integrated than Ritalin, though it may be more subtle (as herbal medicines can be).

Celastrus paniculatus, by Vinayaraj (CCBYSA4.0)

Mugwort and other artemisias

The artemisias are used in traditional medicine for conditions from whooping cough and IBS to burns and haemorrhage – as well as for anxiety and panic attacks. Like Diazepam, one path of action seems to be its effect on GABA receptors, though it outperforms Diazepam against anxiety. Like the other herbs listed above, it is neuroprotective and reduces oxidative stress.

In the lore of the Chumash Indian nation of California, parents stuff a handmade cloth star with Artemisia douglasiana and give it to a hyperactive child to play with to calm them down. Western medicine rarely employs scent, though it penetrates deeper into the brain than other senses and acts beneath the level of consciousness (which is why people have long spent huge sums on perfumes to make themselves seem sexier or more powerful). The olfactory centre is the ideal site of intervention to modify the behaviour of an overstimulated and anxious child: it is closely integrated with the amygdala which has a primary role in processing sensory input, modulating fear, anxiety and aggression, and making decisions.

As well as delivering the medicine steadily over an extended period, the star also requires that a parent invests time in their child to prepare the gift, perhaps gathering herbs and sewing the cloth together. This would set what NLP practitioners call “anchors” (and what doctors call “placebo”) in the mind that associates the scent and its effects with that act of love. Some of my earliest memories are of being told to sit still, in contrast to this wonderful intervention that integrates the fidgets of a hyperactive child into the remedy.

There seems to be more curative wisdom in this simple cultural practice than in the entire research department of Novartis.

When BBC runs headlines about “ADHD medicine shortage devastating families”, they are simply incorrect – there are plenty of medicines that have been shown to improve attention, including all of the above as well as Kanna, green oats, pine bark… There are hundreds of other traditional medicines which have not been tested yet. The problem isn’t the condition, nor the shortage; it’s a problem of definition, which is the problem with ADHD itself.

Artemisia vulgaris, by R.A.Nonenmacher (CCBYSA4.0)

Conclusion

If Ritalin doesn’t help treat “ADHD”, what is it for?

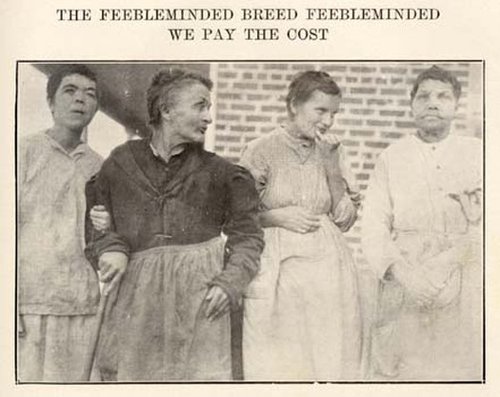

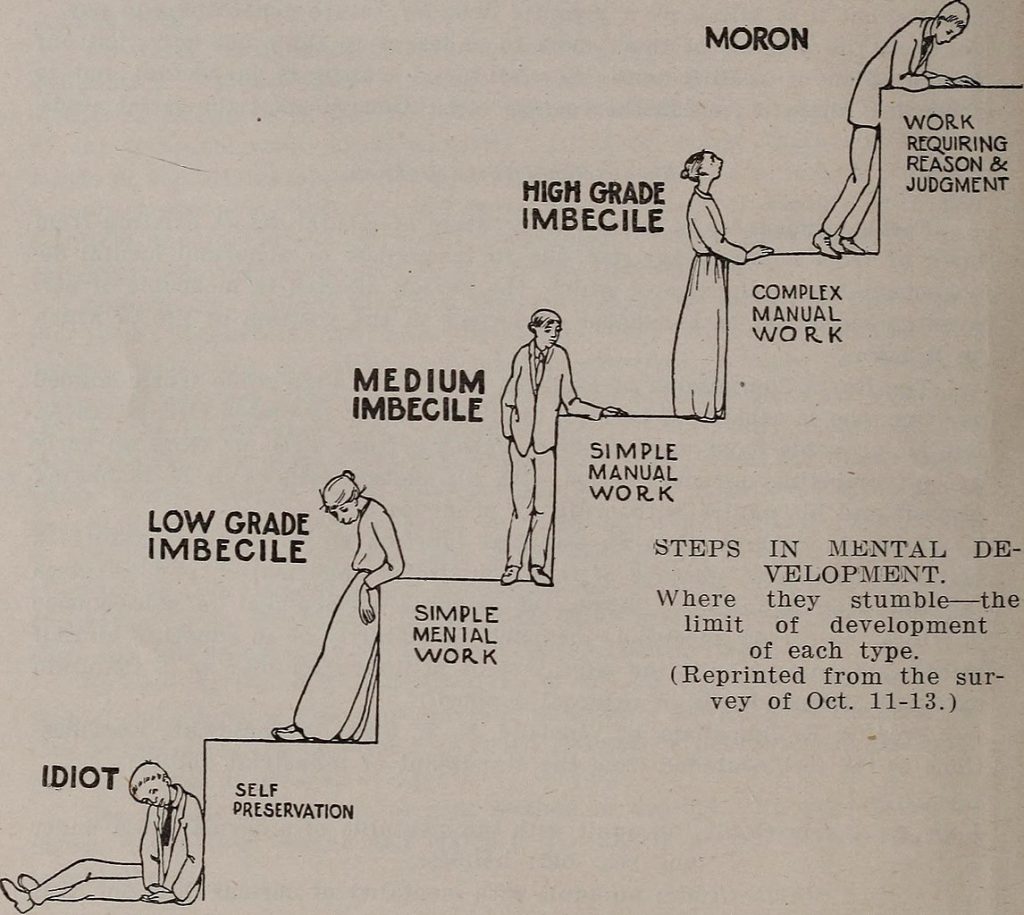

Foucault might have argued that my thinking is called a disorder, and medicated as such, for the same reason that escaping slaves were drapetomaniacs, women with high sex drives were nymphomaniacs and feeblemindedness was a burden on society – because it does not support the economic and cultural framework of a culture that mainly values people for their obedience and economic usefulness.

North Carolina State Board of Charities and Public Welfare, 1922 (PD0)

Mental defectives, 1915 (PD0)

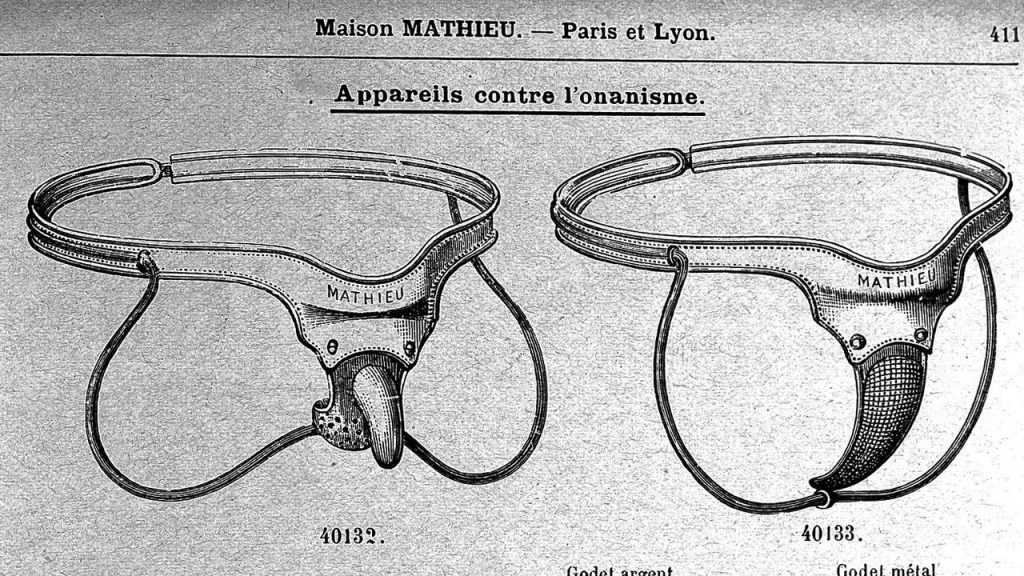

Parents managing their lusty daughters with chastity belts, slave owners slicing off toes, eugenicists seeking to preserve the fitness of their populations: these people were not monsters. They were products of a culture that was monstrous. Most people today agree that the most obvious excesses of the eugenics program were horrific, but a hundred years ago it was the most important scientific movement of the day, funded by such prestigious backers as the Rockefeller Foundation.

Some resisted the zeitgeist, including Dr Hans Asperger, one of the first to explore the upside of neurodiversity. He told a bunch of Nazis in Vienna seeking to exterminate his “little professors” just what they didn’t want to hear:

“not everything that steps out of line, and is thus abnormal, must necessarily be inferior”.

Appliances for treatment of masturbation | Wellcome Collection (CCBY4.0)

The sterilisation of inferior humans has fallen from favour, as have chastity belts and anti-erection devices, so we can rest assured for the time being that curbing uncivilised tendencies with mechanical interventions to the genitals is out of fashion. Today we curb uncivilised tendencies with pharmacological interventions to the brain, and once again the Rockefeller Foundation is funding “the science”. We do this to our children out of a genuine sense of love and affection, and we do it to ourselves. With campaigns like #ADHDAwareness bleeding from the wound that identity politics has inflicted on our psyches, the neurodivergent themselves are vocally demanding that they be recognised as legitimately deficient.

In nature, diversity announces the health of an ecosystem, and I believe that in human nature neurodiversity is a blessing. As Asperger put it:

“It seems that for success in science and art, a dash of autism is essential … the necessary ingredient may be an ability to turn away from the everyday world, from the simply practical, an ability to rethink a subject with originality so as to create in new untrodden ways.”

We’re annoying, to be sure, especially to people who are set in their ways. But from the perspective of a weirdo on the fringes, we’re not half as annoying as nautists. Sometimes neurotypical cognition looks like a baby trying to learn how to use a spoon, self-obsessed and oblivious. And the mess you make of things!

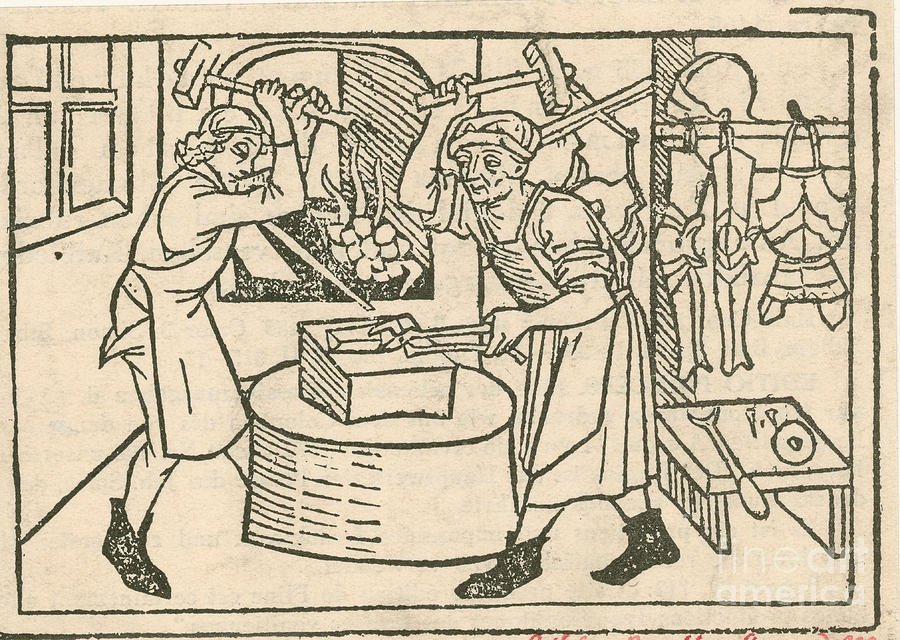

Temperance

A virtue of great interest to metallurgists of the Middle Ages was temperance, and the idea persists today in the idea of “keeping your temper”. In medieval hermetic philosophy, swords represent the mind and the faculty of language, and the training of the mind is likened to the hardening and tempering of a blade. A bladesmith subjects the metal to cycles of extremes, heating it until it glows red and cooling it by quenching it in water or oil. This conditions the sword and makes it hard enough to hold a sharpened edge. The work is complete when a strike to the sword makes it sing.

Woodcut of blacksmiths from The Mirror of Human Life, 1470 (PD0)

The sound resonates because the atoms of the metal have been brought into an orderly lattice that transmits a wave along its length and into the air. This lattice also gives the blade its hardness so it can hold its edge, as any forces it is subjected to are distributed evenly throughout the metal. The final quenching leaves it so hard as to be brittle, so the last process before sharpening is to temper it by heating it evenly in the forge, sacrificing a little hardness for more flexibility. With the correct combination of hardness and softness, a blade well weilded can slice through armour. Its edge cuts and its point penetrates, but it is flexible enough to sing rather than break when it parries an attack – which is a good way for our minds to be.

Since humans developed thumbs that can oppose our fingers and egos that can oppose our natural urges, part of the task of life is to bring our intelligence and creativity into the world harmoniously – to sing our own song in the chorus of the whole. For uncountable generations, adolescence has been a time to experience and confront extremes, and traditional societies invariably supported their passage into adulthood with initiation rituals that subjected the child to extremes. Teenagers are driven to test the limits of our worlds, and the feistier ones can be extremely testing. It’s a testing time for young people and their parents alike, but that’s the deal with parenthood. In my mind, at least, education is what the etymology suggests: e (out) + ducare (to lead). It is about leading something out and assisting with the challenges that entails, not keeping it in.

Keeping it in may be appropriate for a time, but not for a long time. Since ADHD was invented and Ritalin found a market, increasing numbers of people have gone through significant chunks of their adolescence with their neurotransmitters being managed from the outside with pharmaceuticals. They are protected from extremes, denied the opportunity to learn how to harness their powers and kept in an infantile state. But unless they are going to medicate all the way to the Pearly Gates, at some point they will have to rise to the challenge.

The more that can is kicked down the road, the worse it gets because habits of the mind and pathways in the brain become much harder to modify in adulthood. The world becomes less forgiving as you grow older too. A 12-year-old can get into fights with their peers without causing too much damage as their muscles aren’t fully developed; an 18-year-old picking fights is a different matter. Minors have less of a career to derail, fewer serious relationships to trash, no car to drive distractedly… And people – including the police and the justice system – treat youngsters more leniently. An unregulated 15-year-old is annoying. An unregulated 23-year-old is a menace to society and will be punished as such.

Coming back to balance

When people say “I have ADHD so I have a unique viewpoint”, it sounds better than “I have ADHD so I can’t concentrate”, but it is also insulting to nautists (who are, after all, quite a diverse bunch). What a psychiatrist says – what they are financially rewarded to say – need have no bearing at all on how you present yourself, and any feel-good happy zebra factor is bound to be stained by the downsides of the diagnosis. ADHD isn’t a superpower. It’s just a diagnostic category. If you also have a superpower then lucky you. And also poor you! Every comic fan knows that superpowers come with downsides and that superheroes are tested as much by the world as by supervillains.

Leaving aside larger questions and polemics: while Ritalin boosts dopamine, it also brings problems that are not found with other dopamine-boosting practices such as hypnosis, cold plunges, exercise, breath work, herbal interventions, love, sex, crazy dancing and much more. Such practices go beyond managing symptoms to developing the powers that emerge when we come to terms with ourselves and allow our unique natures to flourish.

Coming off of meds is a serious step, as anyone who has dealt with addiction knows. In the case of ADHD, it is as if the bike is liberated from its stabilisers. Suddenly we’re cycling in traffic and wanting to pull a wheelie, but a sense of balance takes time to become established. When people decide to start cycling their brains properly again, they need to develop new habits that do what Ritalin does but better. I wouldn’t recommend anyone even begin coming off medication without having established a daily practice of guided breath work for at least two weeks first, and then keeping it up daily for at least another six weeks. A therapist or hypnotherapist could be a great help, so could a stack of herbal supplements and a support group or neurodivergent mentor.

Part of the work is developing self-love, and – without going too deeply into the changes in culture over the last fifty years – many of us have grown up without good models of care from our primary caregivers. This affects both nautists and the Asper(ger)ational, but differently. Growing up weird is especially tough when your parents don’t have the resources or framework to help you deal with it.

To begin with, if you believe you are managing a pathology rather than nurturing your genius, you haven’t embraced your own cognitive style yet. Self-love begins with self-acceptance, and that may require rejecting the labels, projections and expectations put upon you – including those from other people who want you in their deficient and disorderly spectrum, sharing their hashtags. Of course, I have traits in common with other people with an ADHD diagnosis, and some of my closest friends are functionally catastrophic individuals who live in chaos. But I share far more traits with Donald Trump, Bruce Lee and Audrey Hepburn (number of eyes, kidneys and fingers, for example). It is our differences, not our similarities, that define us and make us unique and interesting, and if there is any hope for us at all it is in the integration of diversity rather than the fragmentation of humanity. So come round, let’s have a party, you can help me organise a cupboard and I’ll have a rant about the Oxford comma – we need each other. Besides, I don’t want to be defined alongside people with a mental disorder and an acronym, and I’d rather not be set apart from the rest of humanity any more than I already am.

Maybe there’s no collective noun because we aren’t much of a collective?

Psychiatric drugs keep us from the extremes, they keep us from sharpening and tempering our own unique minds until they sing; ultimately, I believe, they keep us from reaching our full potential. Of course, many people who use Ritalin are still creative, but how much more creative might they be if their innate powers were unleashed rather than tethered? Perhaps, scaling out to view history and humanity as a whole, the real tragedy is that these interventions keep from the world the solutions we desperately need to rise to the challenges that we face in the 21st century – the kind of solutions that come from violently creative people thinking outside of the box.

Ω

Coda (to a coder). I did eventually get hold of an earlier version of this piece that wasn’t erased, as a tech genius who had edited it raided his cache for me. I’d say he’s been on the Spectrum since he was born, but he’d upgraded to an Amstrad PC1512 by 1986 and today he is programming AI Large Language Models. Thanks John!

Ω

For more on how “The Science” manages our perceptions of reality in a manner most unscientific, check out my book Science Revealed. For a deeper dive into neurodivergence, opposable thumbs and the revolutionary potential of thinking differently, have a look at Neuro-Apocalypse. And if you think hypnosis can help, try the free taster sessions at pattern-interrupt.co.uk.

Ω

HancockHour episode link here

See more of Danny at https://www.dannynemu.com/

If you would like to speak to me, I’d like to tell you how ADHD medicines killed my son. It started out as ADHD, with Ritalin prescribed. he was 10yo. Almost 30 years later and numerous other diagnoses, and even more harmful mental health drugs, my son died, from an overdose and all alone in his apartment. He was found just a few days after his last visit to a mental health hospital. All the so-called medical professionals are who I blame for his death.

What a breath of fresh air, albeit also re engaging me with a sadness and despair I feel I have raged about at various stages of my life. As a retired psychotherapist, I recently spoke to a mental health worker who said to me, what are we going to do? We don’t have enough drugs for the number of people with ADHD. My short response was, we stop medicating this ‘so called condition’ and change the way we live our lives. That was maybe a somewhat flippant answer to a more serious problem that is so brilliantly addressed here in this article. But 30 years ago when my children were young, the ADHD/Ritalin culture was emerging. I knew many people medicating their children with Ritalin. And, as the pharmaceutical companies pushed their drugs, the world of trauma and individual uniqueness (albeit yes, sometimes quite challenging), became increasingly medicated and pathologised to the detriment of many children. This article should be on the curriculum for all those studying or treating those with so-called ADHD and other such behavioural/mental health challenges.

素晴らしい記事をありがとうございました。意見に心からの同意を示します。私は日本人です。そしてリタリン被害者です。服薬していた1994年~2011年までの記憶がありません。その被害を解決するために精神医療について、薬理について、製薬会社について、広告と資本システムについて勉強しました。2011年からの人生のすべてをかけて、今ようやく答えを手に入れました。リタリンはなんのためにあるのか?「麻薬とは人類にとってなんのためのものなのか?」これの答えです。ハンコック氏の提言にもあるように、その答えはシャーマニズムにありました。私は東洋からそれを証明します。古代も現代も、本来は「よい未来・しあわせに生きていくため」を目指しているものです。それは医者も患者も西洋も東洋も、他すべてが目指しているもののはずです。私は20年間の人生を失いました。未来ある子供たちに同じ思いをさせたくない。医者が金儲けのために子供たちの「よい未来・しあわせになれる可能性」を潰したくない。私は、私の体験と日本の科学と遺跡と神話をもって証明します。リタリン(麻薬)とはなにかを。

English machine translation:

Thank you for the wonderful article. Show your heartfelt agreement with the opinion. I am Japanese. And I am a Ritalin victim. I have no memory of the period from 1994 to 2011 when I was on medication. In order to resolve the damage, I studied about mental health care, pharmacology, pharmaceutical companies, advertising and capital systems. After spending my entire life since 2011, I finally have the answer. What is Ritalin for? “What are drugs for humankind?” This is the answer. As suggested by Mr. Hancock, the answer lies in shamanism. I prove it from the East. In both ancient times and modern times, the original aim was to “live a good future and live happily.” That should be the goal of doctors, patients, the West, the East, and everyone else. I lost 20 years of my life. I don’t want my children, who have a bright future, to feel the same way. I don’t want doctors to destroy children’s “potential for a good future and happiness” just to make money. I prove this with my experience, Japanese science, ruins, and mythology. What is Ritalin?

日本ではこれらを話し合う人も場所もないのです。だから有益な記事を読むことができてうれしいです。ありがとうございました。そして、メアリーさんへ。I am terribly sorry for your loss. My heart hurts for you.