Was there a secret tradition of psychedelics in medieval Christianity? Can evidence of this tradition be identified in the presence of psilocybe mushrooms in Christian art?

These questions are a hot topic of debate within psychedelic academia. On grahamhancock.com, we have provided a platform for this debate between Dr Jerry B. Brown and Tom Hatsis.

Dr Jerry B. Brown, an anthropologist and ethnomycologist, argues for and provides evidence of Amanita muscaria and psilocybe mushrooms in Christian art in his book, co-authored with Julie Brown – The Psychedelic Gospels. In November 2021, they were featured as Authors of the Month on grahamhancock.com.

Tom Hatsis, a historian of psychedelia, has written a review of The Psychedelic Gospels, making a case that there was no secret psychedelic tradition in medieval Christianity and that there is no ‘holy mushroom’ to be found in Christian art. In February 2022 Tom was featured as Author of the Month on grahamhancock.com.

Tom Hatsis’ review can be seen here: https://grahamhancock.com/hatsist1/

Dr Jerry B. Brown’s reply to this review can be seen here: https://grahamhancock.com/brownj1/

(Portions of this article come from Hatsis’ forthcoming book, The Mushroom Heretic: In Search of the Psychedelic Christ).

The most recent book (although it is now a few years old) to argue for the mushroom in Christian art hypothesis (or MICAH)* comes from Julie and Jerry Brown, authors of The Psychedelic Gospels (2016). Explaining in detail why the Browns’ MICAH makes historians blush remains a bigger undertaking than the word count allotted for this short article. So I’ve had to make a few decisions approaching this topic, including breaking this article down into five parts:

First, I’d like to unpack how historians adjudicate historical claims by laying out the criteria we use.

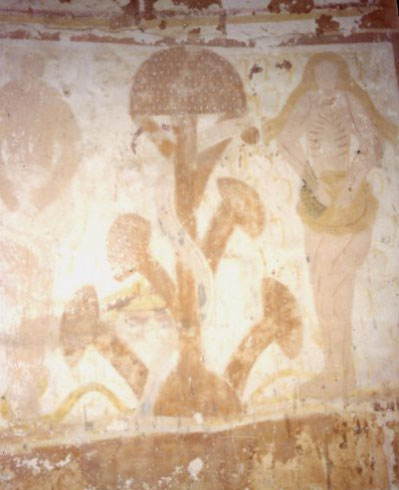

Second, since space is limited, it will be impossible to elucidate every historical foible found in The Psychedelic Gospels. Therefore, I wish to focus on only one image—arguably the most famous and important supposed MICA—known popularly as the “Plaincourault fresco.”1 The Browns believe the fresco depicts an amanita muscaria (the classic red-topped, white-flecked mushroom of fairy tales and Smurf housing projects). In this section, I will give a brief history of how this image appeared in popular culture.

Third, I will discuss chapter 7 of The Psychedelic Gospels titled “Battle of the Trees,” as it is here where the Browns make their case for the Plaincourault fresco depicting a giant mushroom. As will be demonstrated, this chapter, like the rest of their book, is a patchwork of misleading conversations, historical ignorance, scholarly misrepresentation, and, in my opinion, an ego-driven narrative.2 Consider my critiques of this chapter a microcosm … or should I say, microdose, of their entire book.

Fourth, I’d like to run the Browns’ claims through our historical criteria to show why there is reason to doubt their conclusions about the fresco. Since the MICAH is a historical question and since the Browns want their historical claims about the MICAH to be taken seriously, then surely it follows that they wouldn’t mind if we run their hypothesis through the gauntlet of critical historical methodology to determine its accuracy.

As self-appointed “truth-seekers,” the Browns should welcome it, no?

And Fifth, I would like to reveal what the Plaincourault fresco most probably represents.

Historical Criteria

No one knows for certain what happened in the past. We have some good ideas about various people and events, of course, but most of what occurred in history will remain lost to that relentless bastard, Time. So how do we get as close as possible to the truth behind the records left to us? It isn’t easy. Since the past is so opaque (especially ancient and medieval times), historians use a set of criteria to gauge probabilities for historical events. While not perfect, these criteria work marvelously well in service of exposing weak hypotheses and misleading arguments.

While historical criteria can be (and often are) expanded to include other tools of truth detection, the main criteria for which the soft science of history rests are:

Contemporary Attestation: Someone in history attested to whatever historical datum you wish to investigate. They wrote a letter, a law, a chronicle, a diary entry, a poem, a something that you can point to and say, “I want to investigate this.” The best kind of attestation is a written source from the time period you are investigating. You want as many contemporary sources as possible.

Independency: You want independent sources for an event. If you have 20 sources that describe an affair, but the latter 19 sources are just copies of the first source, then you only have 1 source, not 20.

Explanatory Scope: the hypothesis takes into account all of the available evidence relevant to the claim; not just selective evidence. The hypothesis that includes the largest amount of relevant evidence has the best chance of showing accurate historical probabilities.

Anachronism: If I told you that I found evidence that automobiles were invented in ancient Egypt, you would no doubt respond with skepticism. As you should. Because my alleged “evidence” about ancient Egyptian automobiles does not jive with the historical realities of Egypt. It is anachronistic.

Avoiding Ad Hoc: you want to use the least amount of non-evidenced assumptions. The more non-evidenced assumptions needed the more flimsy the hypothesis. Now, because we are always dealing with incomplete evidence when it comes to historical constructions (especially the ancient and medieval worlds) we do have to make some assumptions. However, we cannot base our entire hypothesis on ad hoc arguments.

Explanatory Power: the hypothesis does not force a conclusion.

Bonus Criterion!

Your Ego is not Evidence: While this criterion isn’t normally found with the other rules of historical engagement, I am adding it because, I believe, The Psychedelic Gospels demonstrates this through contrived conversations, misrepresentation of other researchers, and unabashed biased assumptions—the Browns’ egos are unrepentantly wrapped up in their hypothesis, which drives their dubious conclusions.

And always remember, we are using these criteria to gauge probabilities for the best explanation.

These criteria are the scientific methods of historical detective work. If you are not applying them to your hypothesis to gauge its probability then you aren’t doing history; and if you aren’t doing history using these critical methods then there is no reason for historians to take your claims seriously.

It really is that simple.

The Plaincourault Fresco

The fresco appears in the Chapel de Plaincourault, a small house of worship found in Mérigny, France. To Julie and Jerry Brown the fresco proves that Christianity not only has some kind of entheogenic history that includes consumption of the amanita muscaria mushroom, but also that this knowledge survived into medieval times.

The Plaincourault fresco was painted in the late 13th century. Notwithstanding some comments about it from the early 20th century (discussed below), its introduction to popular Western culture occurred in 1970 with the publication of John Marco Allegro’s The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross. Therein, using a sizable amount of fabricated linguistics,3 Allegro claimed that the New Testament was written by Hebraic high priests (apparently quite talented in ancient linguistics in a way that no modern scholar believes was possible in the ancient world)4 who encoded their secret sex and mushroom-based religion into stories about a healer/rabbi named Jesus. As the original authors died off, later adherents of the faith slowly forgot that their religion was based on worship of the mushroom and instead started to worship the fictitious healer/rabbi Jesus.

However, Allegro claimed that “recollection of the old tradition” had survived into medieval times, as evidenced by the Plaincourault fresco.5 But it should also be noted that the Plaincourault fresco represents a very little part of Allegro’s book, which is grounded in Semitic philology, not art. Allegro only wrote three sentences about the fresco in his 200 page The Sacred Mushroom. In our day, these three sentences have been blown up to larger proportions than Allegro ever anticipated. Moreover, he wrote six books after The Sacred Mushroom and never brought up the subject again. His three sentences in The Sacred Mushroom comprise the beginning and end of Allegro’s thoughts on the topic of mushrooms in Christian art. So while he certainly thought the Plaincourault fresco represented a mushroom, he didn’t think there were more mushrooms buried in other works of Christian art. He wanted to end Christianity by showing it to be a fraud based on nothing more than pagan drug use; he had no idea he would inspire 21st century New Agers like Julie and Jerry Brown to build a new version of the faith based on the sacred mushroom of the “Cosmic Christ” supposedly being found in art.

It’s an odd set of circumstances, I’ll grant you.

But the historical irony is delightfully comical.

Far more intriguing is another irony: the Browns believe that Allegro was wrong about his philological arguments. They therefore find themselves in the awkward (and hypocritical) position of disagreeing with The Sacred Mushroom—the very foundation on which they base the MICAH! It seems that the Browns still found affection for the general concept of mushrooms in Christianity, and so (like others before them)6 moved the conversation away from ancient Semitic philology (Allegro’s argument) and over to the question of whether or not mushrooms appear in Christian art. The Plaincourault fresco provided all the evidence needed for this shift. And so they simultaneously built a new case for the sacred mushroom out of the ashes of Allegro’s bogus and dead hypothesis.

As you no doubt see, there is a certain amount of cognitive dissonance embedded in all this.

So Plaincourault is the linchpin. It allows true-believers like the Browns to release themselves from Allegro’s (admittedly spurious) linguistic argument while simultaneously morphing it into a new argument about the MICAH. Now all they have to do is find any bulbous foliage in any medieval Christian art and say that it represents the sacred mushroom.7 This is far beneath even the most elementary standards of historical truth detection … and it gets even worse.

The Claim

The Browns entered Plaincourault Chapel on July 19th 2012. As they inspect the fresco, Julie immediately notices that Eve and Adam are covering their private areas with “mushroom caps, not fig leaves.” This continues a trend found throughout The Psychedelic Gospels: Julie or Jerry will make an elementary comment that jives with their biases, convince themselves it’s true, and build from there without any critical thinking or analysis of evidence, or, at times, even the most humble self-awareness. Despite Genesis clearly stating that Eve and Adam covered themselves with fig leaves (Gen 3:7)—and there is nothing about the fresco to suggest otherwise—Julie has determined that Eve and Adam are covering themselves with mushrooms. Her explanation is both ad hoc and lacks explanatory power, as she is clearly forcing this conclusion.

Next, Julie notices that Eve and Adam appear “skeletonized” in the fresco.8 A plausible explanation might be that eating the forbidden fruit made them weak or frail. After all, Genesis states that to eat the fruit meant to “surely die” (Gen 2:17). And so here we see them withering away. They do not die, of course, but instead are cast from the Garden to toil the earth; although their bodies look like death.

Am I certain of this explanation to account for the skeletonizing of the couple? Not completely. But it at least fits well into what we know about the Eden story.

The Browns, however, did not travel all the way to Plaincourault chapel for perfectly good, naturalistic explanations —again, Julie has another hot take: “Could it be that what this fresco is depicting is that Adam and Eve have actually eaten of the Tree of Immortality, which is the mushroom-tree, and are skeletonized because they are awakening to eternal life?” Of course Jerry agrees with this, commenting that Julie’s interpretation “implies a complete rewrite of the Garden of Eden story.”9 Indeed, simply reading Genesis tells us that Eve and Adam were cast from the Garden before they could eat from the Tree of Life. Nonetheless, Julie’s ad hoc interpretation (which again lacks explanatory power) confirms their bias so who really cares about pesky things like textual integrity and academic honesty?

As the Browns continue to walk about the chapel, Jerry demonstrates that his preferred way of affirming his biases is by asking “the locals” their opinions.10 For reasons that historians scoff, Brown believes he can engage historical studies by asking modern, non-experts their opinions. This, of course, not only breaks both the criteria of contemporary attestation and anachronism, it is also a transgression against basic common sense. Their method looks like this: the Browns will quote their tour guide, Alan Crantelle (because tour guides are known for their rigorous studies in medieval affairs and not for their near-universal practice of exaggerating history for the sake of tourist dollars), who describes the fresco as showing “a mushroom to teach people that they need to elevate themselves spiritually.”11

The qualifications for Crantelle to make such a judgment? None.

His evidentiary reasons for making such a claim? None.

He simply said what the Browns wanted to hear, and nothing matters beyond that. Other locals (now deceased) who the Browns quote include a certain Abbot Rignoux who visited Plaincourault Chapel around 1900 and described it as “a mushroom-tree with several heads.”12 But, again, there is no evidentiary explanation. No explanatory scope; no contemporary attestation. Like Crantelle, Rignoux said what the Browns need him to say, confirmed their bias, and that’s good enough for them.

Such uncritical interchanges with non-scholars constitute half their “investigatory” approach.

The other half of the Browns’ approach is to cite “several scholars” who have “analyzed,” the fresco—i.e., anyone who agrees with them. But it’s all smoke and mirrors; the very scholars cited in The Psychedelic Gospels (save one) lack any evidentiary reason for believing the Plaincourault fresco shows a mushroom.

Take ethnobotanist Richard Evans Shultes and chemist Albert Hofmann. Citing their Plants of the Gods, the Browns claim that they “analyzed Plaincourault … and vigorously disputed Wasson and Panofsky.”13 But when the careful historian checks Plants of the Gods, she finds not any rigorous analysis of the Plaincourault fresco, but instead a mere assertion by the authors that the fresco “bears an uncanny resemblance to the Amanita muscaria mushroom.”14 That’s it. That’s all they say. This is what the Browns consider an historical “analysis” that “vigorously dispute[s] Wasson and Panofsky.” I won’t insult your intelligence by explaining why that is ridiculous.

They also cite ethnobotanist Giorgio Samorini, who visited Plaincourault chapel back in the late 90s and wrote an article about it titled “The Mushroom-Tree of Plaincourault” for the journal Eleusis. Samorini is unique in that he does offer an evidentiary explanation for the possibility that the fresco shows a giant mushroom. He does so by pointing to two other possible mushrooms in Christian art: one from Hildesheim Cathedral in Germany (St. Bernward’s Door of Salvation) and another from a medieval bestiary illumination, catalogued as MS Bodleian 602, folio 27v. At first glance, the door and the folio seem to show mushrooms—for sure, no one would blame Samorini for drawing such conclusions at the time (I certainly don’t—in fact, I used to agree with him). And while Samorini approached the fresco honestly and with a desire to show evidence (not just assertions) for his conclusions, more current research demonstrates that neither the door nor the folio depict mushrooms.15

The Browns’ third non-local “expert” (and I use that term very loosely here) is “Google scholar” Michael Hoffman. I’m not aware of anyone in the field who takes Hoffman seriously and, truth be told, his ideas are not worth wasting the word count allotted in this response. For now, I will say that all the supposed “mushroom trees” Hoffman advances to support the MICAH fit in with the same categories of mistake that the Browns make (see endnote 23 of this article).

So that’s how the Browns derived their “evidence”: (1) preconceived bias (2) assertions from non-experts like Crantelle and Rignoux (3) exaggerating the depth of analysis by scholars who are certainly intelligent, but not critical historians, like Shultes and Hofmann and (4) reprinting once plausible but currently unsupported notions like those offered by Samorini. That aside, the Browns’ approach does not pay any mind to the criterion of contemporary attestation. The Browns cannot find a single piece of evidence from medieval times to support the MICAH, so they base their conclusions about the fresco on the opinions of people living in the 20th and 21st centuries. There is not a historian on the planet that respects such an approach.

Tarnishing Wasson’s Memory

Part of chapter 7 of The Psychedelic Gospels also begins the wrapping of Valentina and Robert Gordon Wasson, amateur mycologists and mother/father of ethnomycology, into a secret Vatican conspiracy to suppress the mushroom, which fully culminates in chapter 12, “The Pope’s Banker.” Fifty years ago, when Allegro first brought the fresco to widespread attention, he was immediately met with a retort courtesy of Gordon Wasson. The Wassons had been interested in the fresco as well, and their investigation into it led them to attend lectures given by top art historians of the day. One such expert was Erwin Panofsky, who responded to Gordon’s inquiries about the Plaincourault fresco in a letter dated 2 May 1952. “Many thanks for your … discussion centered around the fresco of Plaincourault,” Panofsky writes. “[T]he plant in this fresco has nothing to do with mushrooms.” As Panofsky saw it, medieval artists modeled their illustrations of trees, bushes, and shrubs not on the natural world, but instead by replicating them from images found in older manuscripts. Such practices, “in the course of repeated copying,” rendered the trees and shrubbery “quite unrecognizable.” Plaincourault showed not a mushroom, but rather a Romanesque style of “Italian pine tree,” Panofsky assured.16 Not fully convinced of Panofsky’s interpretation, the Wassons made the trip to Plaincourault Chapel anyway. They wanted to check for themselves. For whatever reason, standing before the infamous fresco that 2 August 1952 did not convince them of any previously held amanita muscaria connection. They left the chapel deciding to trust Panofsky’s expertise.*

Once The Sacred Mushroom hit the bookstores, Wasson gleefully made Allegro aware of his error and a much-trumpeted17 (but in reality very minor) debate erupted between the two. The Browns rehash that debate and suggest a financial motive for Wasson’s dismissal of the fresco. According to the Browns, Wasson’s “reluctance to explore entheogens in Christian art” stemmed from his position as vice president of New York banking giant, J.P. Morgan. The Browns draw our attention to an off-the-cuff remark made by another V.P. of J.P., DeWitt Peterkin, who speaks of J.P. Morgan’s ties to the Vatican (the former served as bank for the latter) and the fact that Wasson “used to have private audiences with the Pope.” According to the Browns, who “were flabbergasted” by this news, it meant that Wasson had a “clear financial motive” to keep quiet about the possibility of Christian entheogens, causing an “unethical” internal rift between his research integrity and his “pecuniary ties to the Vatican.”18 The Browns even offer an exaggerated analogy: “it is as if it were suddenly revealed that the foremost climate change denier of our day … had for decades been on the payroll of Exxon Mobil.”19 The Browns reckon that the Wassons dismissed the Plaincourault fresco as a legit mushroom due to Gordon’s position as vice president at J. P. Morgan and that bank’s ties to Vatican City. As if the sacred mushroom weren’t enough of a conspiracy theory itself, the Browns wish to add another layer.

Unfortunately for the Browns, like the rest of their book, this particular criticism proves wholly invalid. The Wassons had very-much considered the role of mushrooms at Plaincourault. They attended lectures on medieval art and even began correspondence with one of the leading art historians of the time, Irwin Panofsky, about this very issue. It was Panofsky who steered the Wassons away from mushrooms at Plaincourault. And yet, even after Panofsky poo-pooed Plaincourault, the Wassons still visited that chapel just to be sure. The Wassons’ own actions and persistent investigation into the fresco (even after Panofsky panned it) completely negate the Browns’ baseless conspiracy theory about any financial motive to keep quiet. Valentina and Gordon were certainly sincere in their investigation into the possibility of the Plaincourault fresco depicting an amanita muscaria mushroom.

And anyway, so what? So what if Wasson was wrong? In one of their typical specious assessments, the Browns seem to think that if they can prove Wasson was wrong, then this automatically proves that the Plaincourault fresco shows a mushroom. I can sense the justified eye rolls coming from the logicians among you ….

The Probable Truth of Plaincourault Revealed

From Allegro to Shultes to the Browns to a few handfuls of Internet trolls, no one has yet offered any actual, lasting evidence that can close the book on the Plaincourault fresco. The Browns, without fail, merely assert the claim, cite anyone who agrees (regardless of expertise in the field or reason for holding such an opinion), and then congratulate themselves for a job well done.

Well, the job is not done.

And neither am I.

Having established that all the Browns’ supposed “evidence” for the Plaincourault fresco supporting the MICAH is nothing more than uncritical speculation, we can start from the ground up and do the real academic exercise needed to solve this mystery. According to the Browns (and many others) the fresco looks too much like an amanita muscaria to be anything else.

But does it really?

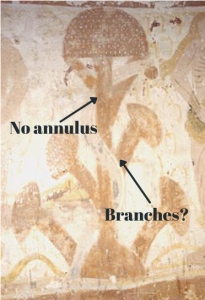

When the Browns claim that the Plaincourault fresco looks like a mushroom, they don’t mean the whole piece, from top to bottom, they just mean the canopy top. Why? Because under the canopy top very little of this image actually looks like an amanita muscaria.

For example, the amanita muscaria features an annulus, which wraps around the upper-part of the stem like a white skirt. Cross-referencing it with Plaincourault, we see that the annulus is absent from the fresco. In its place are two distinct branches holding up the ends of the canopy top; there is no such thing as a mushroom with branches. Moving further down the trunk of the fresco image, we encounter additional protrusions sticking out the sides. To get around this problem, the Browns offer an ad hoc explanation, referring to the “four smaller mushrooms protruding from the long stem.”20 Only such a feature does not exist on the amanita muscaria or on any known mushroom in the natural world. How could these Christians, who have supposedly been worshiping the sacred mushroom for nearly 12 centuries, make such an elementary mistake? Finally, there is no such thing as a giant amanita muscaria; such a concept must be fabricated ad hoc in order to make a mushroom fit the bias.

So when the Browns say this tree looks like an amanita muscaria they really are referring to the canopy top and the spots—the only features of this tree that can conceivably be mistaken for a mushroom. But believe it or not, both those features have explanations—historically contextual explanations—that have nothing to do with mushrooms. Where I believe we all went wrong was not realizing that the canopy top and the spots actually come from two different historical threads. We see a canopy top and spots so we automatically put them together as belonging to the amanita muscaria. We were all wrong.

Let’s put the spots aside for a moment and start with the historical thread that led to the canopy top. Here we have to go deep into history to find its origins. A few years ago I paid a visit to the British Museum with fellow psychedelic historian Sir Michael Crowley. At one point as we moved along the hallways breathing in the ancient relics, I noticed something in an Assyrian relief. Something that looked very familiar. I took out my phone and snapped this picture (right). This is the parasol of victory. Please take note of the nub at the top and the tassels at the bottom (left), as they are important for showing the evolution of this design throughout history.

While not a common symbol today, the parasol of victory was very popular in both the ancient and medieval worlds. From Assyria, the parasol of victory made its way onto Herodian coinage.

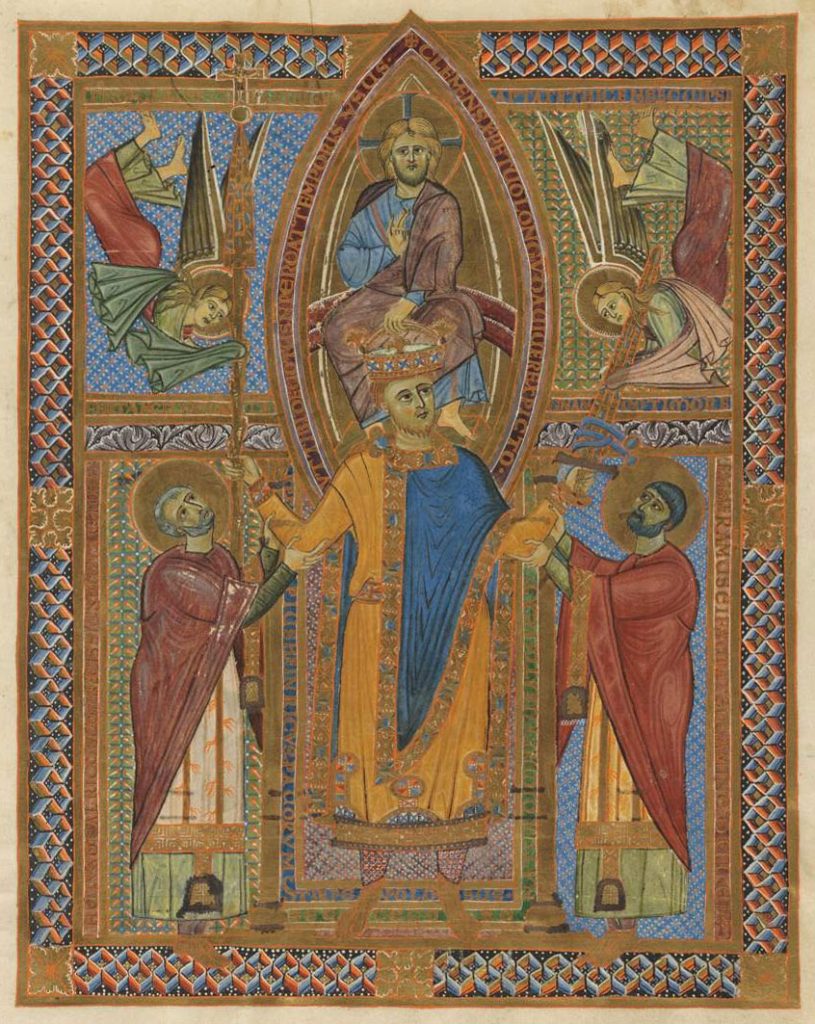

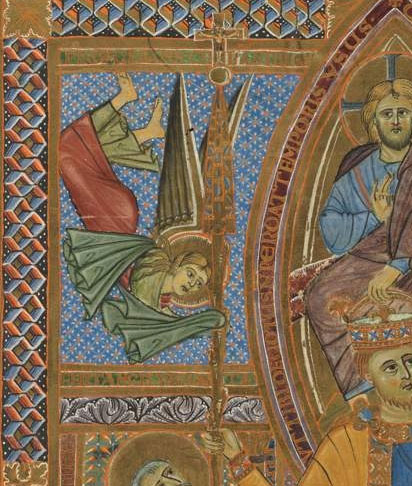

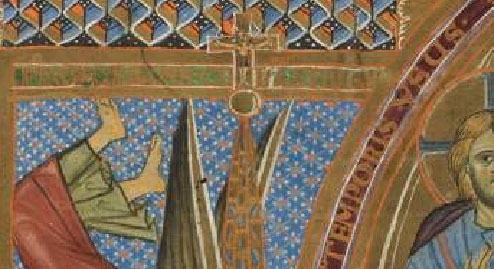

From there it made its way into Rome, and then even after the fall of the Western Empire, the parasol of victory still entered Christian Europe as we see in this most crucial illumination showing the Canonization of Henry the 2nd as it appears in the Regensburg Sacramentary (late 10th century). As Jesus crowns Henry king, the angel to the right is handing him the parasol of victory, complete with the crucifixion at the pinnacle of the nub.

By this time, Christians have fully adopted the parasol of victory as a symbol of Jesus’ reign over all humankind. As the parasol-tree trend rolled through the centuries, sometimes the tassel leaves appear, but not the nub at the top as we see with this image from the story of blind Bartimaeus from Jericho. Other times, we get the nub (in red), but not the tassel-leaves, as we see with this folio showing the lore of the salamander.21

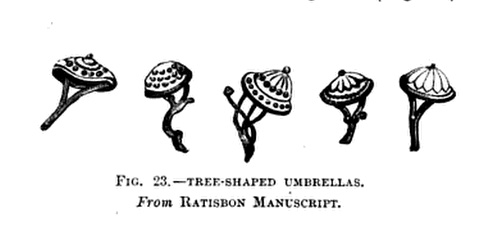

But most damning for the MICAH is still to come. In a text called the Ratisbon Manuscript dating to the 1490s, these parasol trees also turn up. I have been unable to get my hands on this manuscript, but C.F. Gordon Cummings did in the late 1800s, and in her own work reproduced some of the trees from the earlier manuscript. And here they are:

The “tree shaped umbrellas”; for now, we can only assume that that’s what they were called in the earlier text. We have numerous, unambiguous images of the parasol of victory, fulfilling the criterion of explanatory power. We have nothing for the amanita muscaria. We also have the parasol of victory in writing: the Latin word for a “large umbrella” is “umbraculum.” Incidentally, there is no Latin word for “large mushroom.” In fact, there is no known word for “large mushroom” in any language of the ancient or medieval worlds—yet they all had a term for “parasol of victory.” And the parasol revelation doesn’t just topple the Plaincourault fresco—most every canopy-topped looking tree will suffer this fate.22 And yet, it is only one category of mistake that the Browns make. There are, in total, five categories of mistake that every piece the Browns offer fits into neatly.23

So that explains the canopy shape. But what of those damn spots? To uncover this mystery we have to start not with the “Plaincourault fresco,” but with the six other frescos found in the chapel. While we were all fixated on the one alleged “mushroom” fresco we overlooked the other six, which offer clues telling us what the scene in Eden represents. Those other frescos are: the Mother and Child, the flogging of Jesus, the crucifixion, Christ Pantocrator, St. Eloy shoeing a horse, and Reynard the Fox—let’s start with this last fellow.

Reynard the Fox was a popular medieval folk character whose origins remain unknown. The Browns do not mention Reynard because they wish to present Plaincourault chapel as some sort of overly-sacred mushroom meeting place. And yet, Reynard was a secular folk character who was often up to mischief. What was this popular, trickster-figure fox doing in such a holy place? Suddenly the hallowed walls of Plaincourault Chapel are a little less hallow—which is why the Browns cunningly left the fox out of their book, ignoring the criterion of explanatory scope.

So why are these other frescos so important? Because they tell the studious medievalist what is probably going on at Plaincourault chapel—and mushrooms play no role whatsoever. All these frescos represent medieval plays. One of the points the Browns stress in their book is that Pope Gregory wanted to use art to teach the stories of Jesus to the illiterate masses.24 And the Browns are correct here. However, as per their usual, they bent Pope Gregory’s words to suit their needs. Pope Gregory wasn’t talking about frescos and paintings (as the Browns imagine), but rather plays—theater.25Three of the most popular kinds of medieval plays were called the morality play, the miracle play, and the mystery play; sometimes all three were seen in conjunction. Such is the case with Plaincourault chapel: Reynard the Fox represents the morality play; St Eloy represents the miracle play; and the Eden/Jesus26 frescos show one of the most popular mystery plays of medieval times: “The Paradise Play.” The so-called “Plaincourault fresco” does not stand alone, but instead acts as a single panel of a larger story: The story of the “Second Adam”27; the story of the Fall from Paradise and how the birth, death, and resurrection of Jesus atones for the sins of humanity.

Cool trivia, bro … but what about the spots?

While everyone from Panofsky to the Browns refers to these kinds of trees as “mushroom trees” such trees already have a name dating to medieval times. And that name is paradeisbaum. The paradeisbaum was the central prop in the Paradise Play. This play would be performed on the Feast Day of Adam and Eve, December 24th, our Christmas Eve. As part of this play, participants would hang communion wafers—small, round, white communion wafers—on the branches. That is what those spots are. The tree begins as the tree of temptation; just before midnight the performers hang the communion wafers on the branches. This ushers in December 25th, the savior is born, bada boom bada bing—the Tree of Sin becomes the Tree of Paradise, the paradeisbaum. Historian and theologian Francis Weiser sums, “… in the fifteenth century the custom of decorating the Paradise tree, already bearing apples,* with small white wafers representing the Holy Eucharist; thus in legendary usage, the tree which had borne the fruit of sin for Adam and Eve, now bore the saving fruit of the Sacrament, symbolized by the wafers.”28 In fact, we have an Old English form of this play found in the York Corpus Christi collection, dating to 1415. It very plainly stages the scene: “Adam and Eve with a tree betwixt them; the serpent deceiving them with apples.”29

Which is exactly what we see at Plaincourault Chapel.

Since the Browns think unwaveringly that the fresco depicts a mushroom, they have ignored all the evidence that demonstrates otherwise—their MICAH lacks explanatory scope.

And now when we look at the tree as a whole, from the branches hanging out the sides, to the other branches holding up the canopy top, to the missing annulus, and now knowing the historically naturalistic, culturally contextual explanation of the domed top and the spots—and their two, distinct historical threads (parasol of victory and medieval mystery theater)—we can say with relative certainty that this is probably not an amanita muscaria mushroom. It’s more probably a tree.

History deals in probabilities.

To Conclude

In the end, Panofsky was correct (although, not terminologically). The image does not show a “mushroom-tree” (a modern term invented by art historians) but rather a Romanesque Italian pine decorated as the paradeisbaum (a medieval term and custom). This prop in one of the more famous mystery plays was well known to medieval French and English folks, but largely forgotten today—especially by New Age “truth seekers” who wish to see mushrooms in the Plaincourault fresco. And that’s most of the problem with the true origins of the fresco: it is based on symbols and ideas that are no longer relevant to us today. How many psychenauts have heard of parasols of victory and medieval mystery theater? My guess is not many. However, if I were to ask how many psychenauts are familiar with the amanita muscaria, I think it’s safe to say there would be more than a decent handful. Recall our bonus criterion: your ego is not evidence. This is the difference between the kind of biased a-history the Browns prefer and the real work of history—stepping outside yourself and trying to approach a topic with as little anachronistic bias as possible. As a psychedelic historian, I would love for there to be mushrooms in Christian art. I think that’d be fantastic! In fact, there was a time in my life when I was a bona fide believer in the MICAH. But as part of the training historians receive, we have an obligation—nay!—a sworn duty to argue the evidence against our preferences.

We have no 13th century (or any other time in history) sources that mention painting mushrooms in Christian art. The Browns are unique in their mutation of Allegro’s original idea in that they do not believe in any kind of secret mushroom “cover up” the way other supports of the MICAH do.30 Indeed, they feel that painting mushrooms in Christian art was a widely-known fact among medieval peoples!

So then where is the written evidence? To give you an idea of what I mean: where is the MICAH in the thousands of pages of anti-heretical writings, over a million biblical quotations in the Church Fathers’ commentaries, all the pagan and Hebraic attacks against all kinds of Christianities, all the Ecumenical councils, not to mention inter-faith spats and scandals within the Church including the Papal Schism, as well as many surviving letters, diaries, chronicles, sermons, councils, volumes and volumes of medieval exempla, all the writings by or about medieval heretics like the Cathars, the Hussites, the Waldensians, the Beggers and the Beguines, the Heresy of the Free Spirit, and Martin Luther’s 95 Theses—not one word about the MICAH in any of it.

How can this be?

The Browns have a very creative, painfully ad hoc answer to this major stumbling block of their hypothesis. Accordingly, they say the mushroom was “too sacred to write about.”31

Come again?

Medieval artists could exhibit mushrooms—hundreds of them, in fact—on mosaic pieces, in illuminated manuscripts, as frescos, and stonework, and that practice wasn’t considered too sacred; but, hypothetically, an Italian merchant visiting France in the 1300s wouldn’t write a letter to his wife about the cool mushroom images he saw at Plaincourault Chapel because it would somehow profane the holy?

This makes no sense.

And what of the thousands of theologians who have come and gone since Paul of Tarsus? Ultimately, one of the Browns’ problems is that they see Christianity as a monolithic religion, unchanged all throughout history. But Christian history is so much messier than that. So many splinter groups and heresies formed. So many scandals erupted within the Church—to think that theologians argued over every jot and tittle of the faith but somehow all agreed to keep quiet about the mushroom for 2,000 years is an insult to common sense.

“Too sacred to write about” is nothing more than an excuse for the total lack of evidence for the MICAH. The Browns may as well argue in favor of the “ice wall” that the “world government” has constructed to guard the secret of Flat Earth.

And yet, we have written evidence that medieval peoples performed plays (like The Paradise Play), which featured the very scenes we see presented at Plaincourault Chapel: The Fall of Eve and Adam, followed by the birth, torture, death, and resurrection of Jesus. The paradeisbaum passes the criterion of contemporary attestation; the “mushroom-tree” does not; if the Browns can produce for us a script for a medieval play that does mention the holy mushroom that would pass the criterion!

But of course, they won’t.

Because none exist.

Because this is baloney.

Baloney that makes the entire psychedelic Renaissance appear to be promoted by sensationalist zealots instead of honest scholars. All any skeptic has to do is point to The Psychedelic Gospels as a basis to dismiss reasonable claims about psychedelic history.

Suddenly we all look foolish.

The Psychedelic Gospels fail every safeguard historians use to protect our craft from bad-faith actors. And in my opinion, it represents the death of legitimate psychedelic history.

So I end this piece asking the Browns the same questions I’ve been asking them for the last five years, which they have successfully dodged, ducked, dipped, dived, and …. dodged:

1. Besides your opinion and the opinions of other non-medievalists, what evidentiary reasons do you have to support your contention that the Plaincourault fresco shows a mushroom?

2. How do you explain away the communion wafers from The Paradise Play as an explanation for the spots, considering all the evidence we have for them

3. How do you explain away the parasol of victory as the basis for the “tree-shaped umbrellas” of medieval art?

4. If the mushroom was “too sacred to write about” …. how do you know that? What are you pointing to (i.e., law, proclamation, anything) that admonishes churchmen and congregants alike to never speak or write about the mushroom? In other words, where is your contemporary attestation that a gag order was put on the sacred mushroom?

5. Why did you neglect to tell your readers that the so-called “Plaincourault fresco” was part of a larger story called “The Paradise Play?”

6. Why did you leave Reynard the Fox out of your book? Was it because he upends your idea that Plaincourault Chapel represents some hallowed mushroom meeting place?

7. Do you still maintain that the Plaincourault fresco shows a mushroom? If so, why?

What evidence do you actually have—besides your belief that it’s a mushroom? I have shown the history of mystery plays (accounting for the spots) and the history of the parasol of victory (accounting for the shape). What corroborating evidence do you have that makes a mushroom the more probable explanation? To reiterate, how do you explain away all the disconfirming evidence for a mushroom and reject the confirming evidence of the parasol and Paradise Play?

8. How exactly did the mushroom stay “too sacred to write about” during all those turbulent medieval years with the overthrowing of various kings, rulers, clergymen—especially clergymen!—popes, antipopes, and various other medieval authority figures?

9. Can you, using the accepted historical criteria as outlined above, demonstrate the MICAH?

As always, I wait with bated breath.

But after five years I at least now know not to hold it.

References

** See what I did there? 😉

11 It is, in fact, one of the very few images that also fools non-specialists, as a recent Psychology Today article, “Spirit Molecules: Allies for Healing and Trauma,” demonstrates.

22 For a thorough investigation of the many misinterpretations found in The Psychedelic Gospels, see Chris Bennett’s “The Fungi-Pareidolia of The Psychedelic Gospels,” accessed via: https://www.cannabisculture.com.

33 In The Sacred Mushroom he included a Sumerian index of 869 words, of which 315 of them are his own linguistic inventions. See John Herbert Jacques, The Mushroom and the Bride: A Believer’s Examination and Refutation of J. M. Allegro’s book The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross (Citadel Press, 1970), p. 12. Some scholars like Dom Sylvester Houedard count the number at 875 with 404 fabrications; see King (1970), 24.

44 The best argument for how illiterate (to say nothing of bilingual) most people in the ancient world comes from William V. Harris, Ancient Literacy.

55 John Marco Allegro, The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross, 80.

66 See Clark Heinrich, Magic Mushrooms in Religion and Alchemy; Andrew Rutajit and Jan Irvin, Astrotheology and Shamanism; Irvin The Holy Mushroom; John Rush, The Mushroom in Christian Art.

77Here I am agreeing with a point already made by Andy Letcher, Shroom, 159.

88 Brown and Brown, The Psychedelic Gospels, 102.

99 Brown and Brown, The Psychedelic Gospels, 102. This is not the only place in the book where the Browns give ad hoc explanations; see pp. 12-14.

1010 Brown and Brown, The Psychedelic Gospels, 97.

11 11Brown and Brown, The Psychedelic Gospels, 101.

12 12Notwithstanding that such a life form (“mushroom-tree with several heads”) does not exist in real life.

13 13Brown and Brown, The Psychedelic Gospels, 105.

14 14Shultes and Hofmann, Plants of the Gods, 83.

15 15For St. Bernward’s Door, see Chris Bennett’s “The Fungi-Pareidolia of The Psychedelic Gospels,” accessed via: https://www.cannabisculture.com; see also my arguments during my debate with Jerry Brown, “The Great Holy Mushroom Debate,” filmed at Breaking Convention 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZIUmR7o6RGg. For MS Bodl 602, folio 27v, see Hatsis, “Roasting the Salamander,” on psychedelichistorian.com. Samorini cites Chris Bennett who, at the time, did believe folio 27v showed a mushroom. However, since then, Bennett has changed his mind and no longer believes so. Likewise, Carl Ruck, who helped popularize folio 27v, wrote to me saying he no longer believes the illumination to show a mushroom either (pers. comm. 11 Feb 2013). He corrected for this error in his The Son Conceived in Drunkenness (Berkeley, CA: Regent Press and Entheo Media, 2018), 149.

16 16Wasson’s letter reprinted in Brown and Brown, “Entheogens in Christian Art: Wasson, Allegro, and the Psychedelic Gospels” Journal of Psychedelic Studies (2019), p. 4.

* *The Wassons say nothing of the Plaincourault fresco in Mushrooms, Russia, and History, save one footnote where they express their disbelief that the fresco depicts the amanita muscaria (citing Panofsky); Wasson and Wasson (1957), 87. In Soma: Divine Mushroom of Immortality, Wasson expounds a bit more, but adds nothing of additional substance to his earlier dismissal (Wasson, 1968), pp. 179-180.

17 17Both Jan Irvin and the Browns greatly exaggerate the importance of this debate. They do so because they are operating under a faulty and illogical premise: they seem to think that if they can show that Wasson and Panofsky were wrong about the Plaincourault fresco it automatically makes Allegro correct about the Plaincourault fresco.

18 18Brown and Brown, The Psychedelic Gospels, 181.

19 19Brown and Brown, The Psychedelic Gospels, 182.

20 20Brown and Brown, The Psychedelic Gospels, 97.

21 21This is the illumination that Samorini (and others, myself included) mistook for an amanita muscaria. Besides retaining the nub at the top (which automatically demonstrates we are dealing with the parasol of victory), amanita muscaria do not have blue tops and green stems. Please also note the smaller branches sticking out the sides—just like the Plaincourault fresco.

22 22Michael Hoffman, mentioned earlier, falls for this one quite a lot.

23 231. They derive from the aforementioned parasol of victory; 2. They are open to alternative, naturalistic interpretations that require fewer leaps in faith; 3. They are objects that were never intended to represent mushrooms at all; 4. or are so desperately lacking in their “mushroomness” it’s a wonder the Browns submitted them as evidence in the first place. 5. The photos the Browns use are not clear enough to confirm or deny the presence of a mushroom.

24 24Brown and Brown, The Psychedelic Gospels, 118.

25 25Bernd Brunner, Inventing the Christmas Tree, 15; Francis X. Weiser, The Christmas Book, 94.

26 26I.e., Eve and Adam, Mother and Child, The Scourging of Jesus, Crucifixion, and Christ Pantocrator.

27 27See Paul’s letter, 1 Corinthians 15:45-47.

* *Which we see the serpent offering Eve in the fresco.

28 28Weiser, The Christmas Book, 118.

29 29Quoted in W. C. Stafford, “History of the English Drama,” in The Repository of Arts, Literature, Fashions and C, Third Series, Vol. 10 (1827), 210. Italics mine.

30 30Andrew Rutajit, Jan Irvin, John Rush, Carl Ruck, and the late Jack Herer and James Arthur all believe that the mushroom was “covered up” …. despite, apparently, the hundreds of mushrooms they think exist in art. More of that cognitive dissonance needed to believe this tripe…

31 31Quoted from Psychedelica, Episode 10, “The Holy Mushroom.”

what a long piece of trash that was,the guy has no idea what hes saying absolute rubbish.mate you no nowt about it.

the mushroom litters human history and is displayed on every continent.

You forgot to mention a single piece of evidence for your claim.

You also forgot to actually address any of my points.

I’ll take that as a win for the side of truth 🙂

A thankless task well done. The most exhausting part of explaining discoveries in art history to art historians, and to ‘popular’ art ‘historians’ or rather correspondence ‘theorists’, is addressing long held fallacies based on poor theoretical frameworks. The core of the problem is that anthropology, and all the human sciences, do not have an adequate or mature theory of what cultural media are, nor of what human behaviour is. I have offered a structuralist framework for subconscious behaviour, but human science and human pop ‘science’ both remain cultural crafts themselves, serving up what society wants to hear.

In astronomy, amateurs worldwide have made contributions to the science. But in all the humanities involving cultural media, in particular archaeo-astronomy, amateurs tend to clutter the field with compulsive assumptions and vague re-hashes. A reminder that individuals could mature, and some do, but the species never does. Learners graduate, but schools do not.

Let the reader beware of any argument based on correspondence (this looks like that, therefore…). The old diffusion assumption (recently taken to its absurd conclusions by Witzel), is one of the core problems in the human sciences.

We seem incapable of agreeing on the core question of anthropology, as Schroedinger had formulated: Who and what are we? Judging by most books serving pop anthro, and pop art history, from De Santillana, to Von Daniken, etc, culture evolves and devolves. I have offered much evidence that culture is static, sustained by subconscious inspiration, and differs only in styling, which in itself is meaningless, but enables re-appropriation. And here is a clue to one of the eternal motives of pop historians: to claim shreds of correspondence as ‘discoveries’ and become cultural gurus. Which is good and well for the purposes of culture, but tiring stumbling blocks in the quest to turn anthropology from a craft to a science.

The adage that history is a set of fictions we tell one another, is a reminder that history remains engaged in the struggle to rise from the level of cultural craft, to a science. Even the ‘panarchic discourse’ of an untraceable number of influences (Gunderson and Holling) is still a version of the fiction of diffusion (which plays minor roles in some aspects of culture).

The tiring debate above would be worthwhile if you could spell out your theoretical framework of history. Your rules of thumb are helpful, but they do not answer Schroedinger’s core question: Who are we? And by implication, who, what, where, how, when, and how do events become history?

In a world where Witzel could be a scientist, and the religious mushroom correspondence cult could make gurus of posseurs, the human sciences need to start from scratch to fulfill their joint function: to reveal the place of culture in nature.

I wrote about this article and Jerry Brown’s article: https://cyberdisciple.wordpress.com/2022/02/25/mushrooms-in-christian-art-discussed-by-tom-hatsis-and-jerry-brown-at-graham-hancocks-site/

Excerpts:

Brown asked me to consult on some details of Hatsis’ claims about ancient and medieval art and history, and I am cited in his article. Hatsis’ discussion of “parasols of victory” (whatever they are) and “paradeisbaum” (misspelling of paradiesbaum) is a wall of factual errors, misinterpretations, and confused historical reasoning.

Hatsis brands himself “psychedelic historian,” but the mistakes in this article make that brand look especially superficial. He should be embarrassed by the mistakes and take it as a clue that he needs to spend more time with the material he claims to be an expert on, less time lecturing others about historical methodology.

I just realized it was you!

If you’d ever like to have a friendly Zoom debate and post it for the world to see, please let me know.

I am not scared of your hyperbolic and baseless attacks, but I reckon you are too scared to face me in real time, yes?

Step up to the plate or go find someone else to troll.

No, Tom. I have a strict rule: don’t debate narcissists.

If you need something proofread before you publish it, send it to me at [email protected] and I will tell you if you are misreading sources and where your historical arguments need improving. We could have saved you the embarrassing blunders in this article.

Lol, because of a misspelling?! It’s incredulous that you are replying to Hatsis’ incredibly well thought out evisceration of the Browns’ “work” (ignorant propaganda) with ad hominem attacks, and no actual refutation of anything hatsis says and proves. In rhetoric, we have logic, pathos and ethos. Here, you barely employ logos and your intended ethos, that you are a hired consultant of the brown’s, is…ha! I’m embarrassed for you! YOU should be embarrassed. Excellent work Tom!

Tom, there’s only one word for your claim that the Browns’ thesis is driven by ego: projection. Time to put your big-boy pants on and stop making it all about you.

Tom, I wish the psychedelic world had pulitzers because you deserve one. It’s a cliche at this point, lamenting the stark irony in how a community of alleged truth seeking psychonauts can succumb to the kind of intellectual dishonesty you’ve exposed. The likes of Jan Irvin and the Browns, and the exposure they’ve received, while being the historian equivalent of the Qanon shaman tells us that interest and consumption of psychedelics is no measure of integrity, intellectual or otherwise (as if Charles a Manson wasn’t a loud enough example). You did well Tom – don’t let the bastards get you down!

Utter Bosch!

I was really interested to see what your basis was for claiming this fresco does not depict a mushroom. I was disappointed, to say the least and am surprised you were given the mic on Graham’s forum now that I have read your work.

The idea that the fresco shows a pine tree, even highly stylised is so laughable I don’t really think the burden of proof is on anybody to “prove” to the contrary.

As for “parasol of victory was very popular in both the ancient and medieval worlds” – this assertion is apparently “proof”?

The Old Ambrosia society website had a wealth of Images of mushrooms in Christian works, so many that they filled a small book. It is a shame that it no longer exists.

The only other actual “evidence” in this conflated article is the “paradiesbaum” – you are saying that as there is evidence of a play where Adam and Eve dance around a tree covered in wafers (although this is not explicitly mentioned in the source) then apparently this proves that the fresco depicts a tree not a mushroom?!

This article is idotic egocentric rambling at it’s finest, and I think having read Chris Bennett’s rambling article too (where he hilariously attacks other’s work as being too padded out whilst dragging his points out into such a dilution it is hard to even see what point he is actually making through most of it), it would appear to me that there are, as usual, more people trying desperately to prove themselves than anything historical of any real merit. Either that or there is another agenda.

I haven’t read the Brown’s work, I don’t know if I’ll bother as the fact you are all arguing like children suggests you have little to offer other than arguing over breadcrumbs.

You fail to mention Allegro’s extremely important work on and quite unique access to the dead sea scrolls which lead him to the conclusions he draws in the sacred mushroom and the cross, Michael Baigent amongst others has written some useful information on this, although until the scrolls are available to mass study we may never know the truth here. The fact that after some 60 years they are still predominantly under lock and key suggest there maybe something challenging about their content, who knows if mushrooms are involved.

The Fresco shows a mushroom, show it to practically any man, woman or 5 year old child and they would state the same. If it walks like a duck… this is not ego first, historical analysis second it is the most obvious conclusion by far and your argument appears little more than a cry for attention.