Was there a secret tradition of psychedelics in medieval Christianity? Can evidence of this tradition be identified in the presence of psilocybe mushrooms in Christian art?

These questions are a hot topic of debate within psychedelic academia. On grahamhancock.com, we have provided a platform for this debate between Dr. Jerry B. Brown and Tom Hatsis.

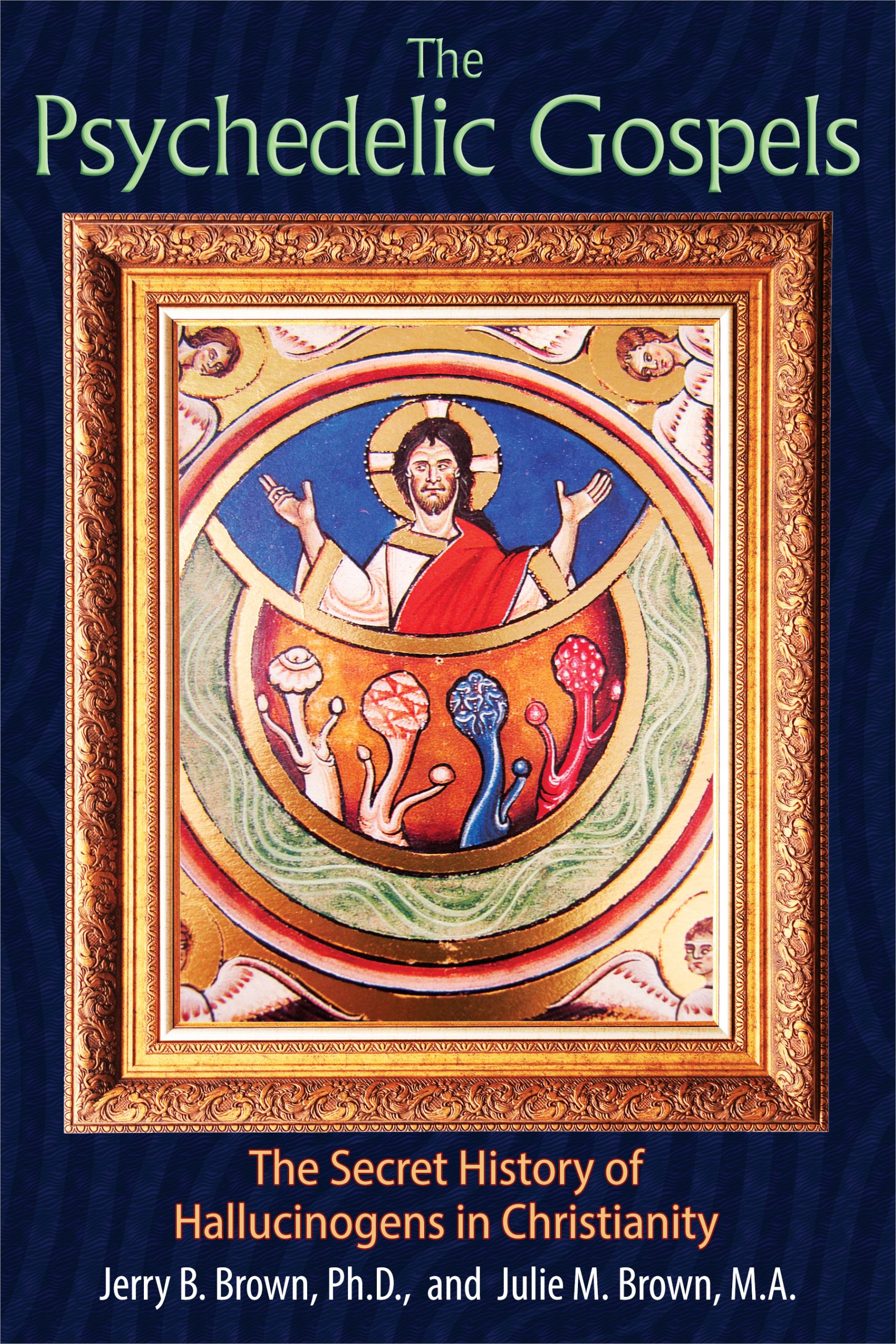

Dr. Jerry B. Brown, an anthropologist and ethnomycologist, argues for and provides evidence of Amanita muscaria and psilocybe mushrooms in Christian art in his book, co-authored with Julie Brown – The Psychedelic Gospels. In November 2021, they were featured as Authors of the Month on grahamhancock.com.

Tom Hatsis, a historian of psychedelia, has written a review of The Psychedelic Gospels, making a case that there was no secret psychedelic tradition in medieval Christianity and that there is no ‘holy mushroom’ to be found in Christian art. In February 2022, Tom was featured as Author of the Month on grahamhancock.com.

Tom Hatsis’ review can be seen here: https://grahamhancock.com/hatsist1/

Dr. Jerry B. Brown’s reply to this review can be seen here: https://grahamhancock.com/brownj1/

By Jerry B. Brown, Ph.D., coauthor The Psychedelic Gospels: The Secret History of Hallucinogens in Christianity, 2016

A WILD RIDE

I stopped publicly debating and communicating with Thomas Hatsis in August 2019, after receiving a slanderous and threatening email from him. I will explain below what promoted this unprofessional outburst.

However, due to the February 2022 posting on Graham Hancock’s popular website of Hatsis’ recent screed against me and The Psychedelic Gospels‒ and implicitly against all scholars who “argue for the mushrooms in Christian art hypothesis”‒I felt an obligation to readers and to the field of psychedelic studies to set the record straight by writing this Reply to the Hatsis Review.

In this Reply, I will also propose a framework for revitalizing the study of mushrooms in Christian art (MICA), and focus the field on the central question: to what extent are psychoactive mushrooms present in Christian history?

Science vs. Religion

As for setting the record straight, let us start with this quote which reveals Hatsis’ main goal, which is to frame the entire study of mushrooms in Christian art as a “science” vs. “religion” debate.

Hatsis: He [Allegro] wanted to end Christianity by showing it to be a fraud based on nothing more than pagan drug use; he had no idea he would inspire 21st century New Agers like Julie and Jerry Brown to build a new version of the faith based on the sacred mushroom of the “Cosmic Christ” supposedly being found in art (Review, February 2022, unless otherwise noted, all Hatsis quotes are from his Review of The Psychedelic Gospels, available here).

Fact Check: First, nowhere in The Psychedelic Gospels (TPG) do we* mention the concept of a “Cosmic Christ” based on the sacred mushroom. What we do say is that “While our findings are startling, it is not our intention to question people’s faith in Christianity, but to uncover a mystery that we believe applies to many religions” (TPG, p. xii).

(*As the sole author of this Reply, I write in the first person. However, when referring to TPG, which I coauthored with Julie M. Brown, I use “we” and “our.”)

Second, as an activist for most of my career, I have been called a few unflattering names, but “New Ager” is not one of them nor is it one that fits my profile (see Jerry B. Brown Wikipedia profile).

Third, and most significantly, the above quote exposes Hatsis’ core strategy, which is to portray himself as a serious scientist, the objective “psychedelic historian,” motivated by the pursuit of truth, while painting me and anyone who advocates MICA as gullible New Agers motivated by a quasi-religious belief in a “secret mushroom cult.”

What I will demonstrate in this Reply is that Hatsis is wrong about numerous details of fact and interpretation when it comes to discussing The Psychedelic Gospels and analyzing medieval works of art. This includes Hatsis’ conspicuous misreading of the “Regensburg Sacramentary,” an early eleventh-century illuminated manuscript, which he describes as the “most crucial” piece of evidence presented in his critical Review of our book.

So, hold on to your mouse! You are in for a wild ride.

HATSIS CANNOT ACCURATELY INTERPRET MEDIEVAL ART

The Holy Lance of the Regensburg Sacramentary

Hatsis wants you to believe that he is an expert on medieval art, fit to judge (and condemn) our interpretations of MICA in TPG from a position of authority. Yet in his Review, Hatsis commits fundamental errors of both fact and interpretation.1

To explain away the mushroom shape in the thirteenth century Plaincourault fresco‒which is iconic in MICA discussions and the main focus of his Review-Hatsis rejects the simple and obvious interpretation that, because the tree looks like a mushroom and acts like a mushroom in transforming Adam and Eve, the tree represents a mushroom.

Instead of applying Occam’s razor, Hatsis argues that the unusual features of the tree derive from two separate sources: the “parasol of victory” and paradiesbaum (“paradise tree” in German). Hatsis’ account of these alleged influences is strewn with errors.

Hatsis: His most spectacular blunder concerns his misinterpretation of an image in the “Regensburg Sacrimnetary”‒an illumination which Hatsis presents as a “most crucial” piece of evidence for the “parasol of victory,” a symbol in Christian art for Christ’s triumph.

In his Review, Hatsis states:

While not a common symbol today, the parasol of victory was very popular in both the ancient and medieval worlds. From Assyria, the parasol of victory made its way onto Herodian coinage.

From there it made its way into Rome, and then even after the fall of the Western Empire, the parasol of victory still entered Christian Europe as we see in this most crucial illumination showing the Canonization of Henry the 2nd as it appears in the Regensburg Sacrimnetary (late 10th century). As Jesus crowns Henry king, the angel to the right is handing him the parasol of victory, complete with the crucifixion at the pinnacle of the nub.

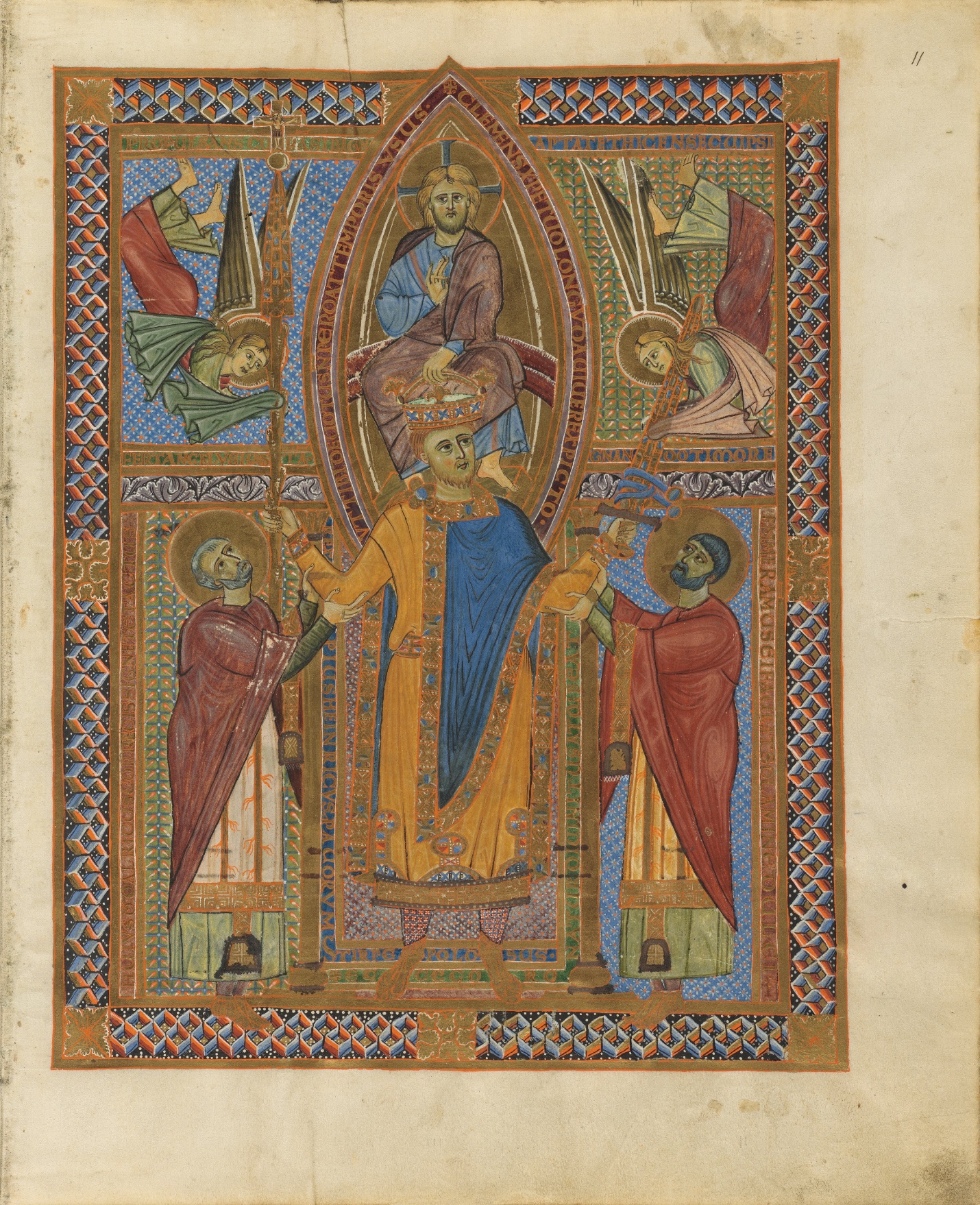

Hatsis claims that the angel in the upper left panel of the image below brings a parasol of victory to the Germanic Holy Roman Emperor Henry II.

Image 24 of Regensburg Sacramentary, created 1002 to 1014

Illuminated Manuscript, Bavarian State Library

Fact Check: I showed this image to Carl A.P. Ruck, professor of Classical Studies at Boston University, who confirmed that Hatsis’ interpretation is dead wrong. According to Ruck, the object is “a lance” not “a parasol.” We know this because the Latin text in the image clearly tells us so.

The Latin sentence inscribed in the green border above and below the angel says “PROPULSANS CURĀ SIBI CONFERT ANGELVS HASTĀ,” which Ruck translates as “Expressing concern/care or setting in motion protection, an angel confers upon him/herself a lance, i.e., takes up arms to protect the emperor.”2

Ruck, an authority on Latin grammar, observes that “Hatsis with the slightest knowledge of Latin should have known that. He obviously has no basis for a sunshade or ‘parasol of victory’.”3

As shown in this detail of the Regensburg Sacramentary below, the capital letters for the Latin word “HASTĀ” are inscribed around the lance shaft in orange letters in the row of writing on the border below the angel, with the “HAS” to the left and with the “TĀ” to the right of the shaft on which the lancehead is mounted.

Any Latin dictionary will tell you that hasta means “spear” or “lance.” Hatsis has completely misinterpreted what he calls a “most crucial” image. Hatsis imposes his own category of “parasol” onto the image, despite the image itself telling us what it depicts!

Indeed, the object brought by the angel is a major Christian symbol: that of the holy lance, not that of the “parasol of victory.”4 Apparently, Hatsis never consulted scholarly resources on the image, which could have easily set him straight. The Holy Lance is the lance that pierced the side of Jesus as he hung on the cross during his crucifixion.

Numerous Factual and Interpretive Errors

Before leaving Henry II and the lance, I call your attention to other elementary mistakes made by Hatsis in his description of the “Regensburg Sacramentary,” based on the U.S. Library of Congress description of this illuminated manuscript. The correct title of the manuscript is “Sacramentary of Henry II,” not the “Regensburg Sacramentary.” The scene is a coronation, not a “canonization”. The Sacramentary dates from the early 11th century (between 1002 and 1014), not the late 10th century.5 These errors betray Hatsis’ sloppy research and disregard for accuracy.

Furthermore, a look at Hatsis’ categories “parasol of victory” and paradiesbaum will confirm that we need pay little attention to his interpretation.

Hatsis portrays these categories as standard, recognized features of ancient and medieval history. Instead, “parasol of victory” appears to be a figment of his own invention, as a database search of major academic journals in Classical Studies and Medieval Studies produces no relevant results for “parasol of victory.”6 Paradiesbaum (not “paradeisbaum,” as Hatsis writes) appears 44 times, primarily in German.

While discussing the paradiesbaum, Hatsis, the “psychedelic historian,” ironically pays little attention to historical context. Hatsis seeks to explain a thirteenth century fresco in central France by citing fifteenth century evidence in Germany and England. Hatsis plays fast and loose with chronology and geography. It is as if all pieces of evidence are floating free of their historical context and can be arranged by Hatsis however he likes.

Furthermore, in TPG we point out it was not surprising to find mushrooms in Christian art, since “Pope Gregory (540–604), known as ‘the Father of Christian Worship,’ believed that paintings of bible stories were an essential tool for the education of the faithful who could not read. In this way, Christian art and images became ‘the Bible of the illiterate’” (TPG, p. 118).

Another significant error in Hatsis’ Review occurs when he attempts to discount this observation by insisting that, when Pope Gregory wrote about teaching the illiterate Bible stories by means of visual art, he was referring to plays rather than images.

Here, I suggest that Hatsis review the text of Gregory’s letters to Bishop Serenus of Marseilles (Ep. 9 and 11), for which English translations and the original Latin are available in a scholarly article focused on the two letters. There is no mention of plays or theater.

In summary, Hatsis’ numerous factual and interpretative errors and his lack of attention to basic historical reasoning reveal his claim to speak as an authoritative psychedelic and medieval historian as an empty boast.

Mushrooms in Christian Art Hypothesis

Hatsis and I agree on three broad points regarding the use of psychedelics in Christianity:

- That psychedelic mystery traditions existed in the ancient Greco-Roman world‒the world from which Christianity first emerged.7

- That some early Christian groups used psychedelic plants.8

- That the thirteenth century Plaincourault fresco painted in a chapel in central France, and through it the topic of psychedelic mushrooms in Christian art, were first introduced to popular culture in 1970 through the publication of John Marco Allegro’s The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross due to the ensuing media frenzy and firestorm of criticism that it caused in England.9

Where we diametrically disagree is on the question of psychoactive mushrooms in Christian art (MICA).

The identification of this Plaincourault fresco was the catalyst for the controversy between ethnomycologist R. Gordon Wasson and philologist John Marco Allegro regarding the presence of psychoactive mushrooms in Christianity. While Wasson asserts that “my book brings the role of the fly-agaric in the Near and Middle East down to 1000 BC,”10 Allegro contends that the Plaincourault fresco confirms the remembrance of an “old tradition” late into the 1200s AD.11 (“Fly-agaric” is the English name for the iconic red-and-white spotted psychoactive Amanita muscaria mushroom.)

Although Wasson’s view prevailed and stymied research on mushrooms in Christianity for decades, a new generation of researchers‒including Clark Heinrich, Mark Hoffman, Carl Ruck, and Giorgio Samorini‒has documented growing evidence of Amanita muscaria and psilocybin-containing mushrooms in Christian art.12

A recent study was coauthored by Fulvio Gosso and Gilberto Camilla, who in 2007 and 2016, respectively, published volumes one and two of Allucinogeni e Cristianesimo: Evidenze nell’arte sacre (Hallucinogens and Christianity: Evidence in Sacred Art). The two volumes describe fifty-two color plates showing psychedelic mushrooms, both Amanita muscaria and Psilocybe-varieties, mainly in medieval Christian artworks from Italy, France, Germany, Switzerland, Poland, Holland, and Russia.

On the back cover of volume 2, the authors conclude that as the evidence for the presence of hallucinogenic mushrooms in Christian iconography becomes more plentiful and more widely distributed, “it seems obvious that they are only a small part of those existing or existed.”

Obviously, Julie and I are not the only researchers to propose that there are psychoactive mushrooms in Christian art–although we are the first to conduct onsite anthropological fieldwork in multiple churches and cathedrals throughout Europe and the Middle East.

A brief overview of TPG is available on Graham Hancock’s Author of the Month website post for November 2021. A 30-minute video of our findings, presented at Breaking Convention 2019 in Greenwich, England, can be viewed here.

Amanita Muscaria and Psilocybe Mushrooms in Christian Art

In attempting to build a case against MICA, Hatsis completely ignores or purposefully distorts four fundamental components of The Psychedelic Gospels which contradict his critique of our book.

First, Hatsis claims that “Plaincourault is the linchpin.” However, our case for the presence of MICA does not rise and fall with the Plaincourault fresco alone. Rather, we document the presence of sacred fungi in nine different abbeys, chapels, churches, and cathedrals that we visited and photographed in Scotland, England, France, Germany, Italy, and Turkey (See map, TPG, p. xiii).

Second, while Hatsis is obsessed with denying the presence of Amanita muscaria as the one and only MICA, we–along with Samorini and other researchers–document both Amanita muscaria and Psilocybe-variety mushrooms, which we found depicted in ceiling paintings, frescoes, illuminated prayer books, mosaics, sculptures, and stained-glass windows in churches dating from as early as 330 CE up to 1230 CE.

For example, moving from right to left in this image below from the Great Canterbury Psalter, an illuminated prayer book, we see a stylized red-and-white-spotted Amanita muscaria next to a blue psilocybin mushroom. Psilocybin turns blue when exposed to air.

God Creates Plants, Great Canterbury Psalter

Folio 1, England, c. 1200

Courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

Third, in focusing exclusively on “historical criteria,” what Hatsis fails to understand is that anthropological studies are frequently based on interdisciplinary research. In TPG, we incorporate the findings of anthropologists, archaeologists, art historians, chemists, classicists, ethnobotanists, ethnomycologists, and medieval historians. In addition, the Anthropological Perspective emphasizes the value of “fieldwork” as the basis for insightful description and reporting.

Fourth, while Hatsis belittles the conversational style through which Julie and I report our findings, he fails to mention that, in our “Invitation to Readers,” we unambiguously state that “This book takes you along, step-by-step, on our decade long anthropological adventure, providing an easily readable account of this controversial theory” (TPG, p. xi).

We did not set out to write a traditional academic work but decided to combine our ethnomycological discoveries with colorful travelogue descriptions and lively dialogue to reach the widest possible audience.

The overwhelmingly positive Amazon reader reviews and endorsements from psychedelic luminaries, such as MAPS founder Rick Doblin, microdosing researcher James Fadiman, and mycologist Paul Stamets, suggest that we have achieved this goal.13

PLAINCOURAULT FRESCO

Hatsis cannot be Trusted to Comment on The Psychedelic Gospels

Before turning to the Plaincourault fresco, I would like to document, using direct quotes from the lengthy discussion of Plaincourault in his Review, why Hatsis cannot be trusted to accurately quote, comment on, or interpret our findings in The Psychedelic Gospels.

Hatsis: The Browns entered Plaincourault Chapel on July 19th 2012. As they inspect the fresco, Julie immediately notices that Eve and Adam are covering their private areas with “mushroom caps, not fig leaves.”

Fact Check: The actual quote reads “Look,” Julie pointed out, “Adam and Eve are covering themselves with what appear to be mushroom caps, not fig leaves” (Emphasis added, TPG, p. 97).

Now we know Hatsis must have seen the qualifying words “appear to be” as they are proximate to the words he cites. Nor is this a minor oversight, because in the next few sentences Hatsis uses this “quote” as the basis for his claim that Julie and Jerry, “will make an elementary comment that jives with their biases…and build from there without any critical thinking.” This is but one example of how Hatsis cavalierly lifts partial quotes out of context and uses them to claim that we are biased.

Hatsis: To Julie and Jerry Brown the [Plaincourault] fresco proves that Christianity not only has some kind of entheogenic history that includes consumption of the amanita muscaria mushroom, but also that this knowledge survived into medieval times. (The technical term “entheogen,” developed as a neutral alternative to the word “psychedelic,” refers to plants and fungi that “generate the divine within.”)

Fact Check: We never claim that this Plaincourault fresco alone “proves” that Christianity has an entheogenic history. In fact, we present nine examples of MICA in our book. Plus, we devote an entire Appendix of TPG to calling for the establishment of an Interdisciplinary Committee on the Psychedelic Gospels to rigorously evaluate “conflicting interpretations of mushroom symbolism in Christian art” (TPG, p. 227).

Tom Hatsis Throws a Temper Tantrum

Hatsis: Near the conclusion of his Review, Hatsis states “So I end this piece asking the Browns the same questions I’ve been asking them for the last five years, which they have successfully dodged, ducked, dipped, dived, and …. dodged:”

Fact Check: The utter duplicity of this statement is confirmed by a simple Google search. TPG was published in September 2016, and over the next few years, between 2017 and 2019, I publicly debated Hatsis on the topic of MICA–both expressing my views and responding to his claims and questions–on at least three separate occasions. I also had vigorous interchanges with Hatsis on this topic during several podcasts, including this one on “Christianity and the Psychedelic Mushroom – A Debate,” hosted by Psychedelics Today on December 25, 2018.

My first public debate with Hatsis, which took place in 2017 at the Exploring Psychedelics conference, was titled “Sacred Mushrooms in Christian Art? – a Dialectical Conversation.” The second was a 2018 exchange of views presented in a 30-minute Gaia TV documentary on “The Holy Mushroom Theory.”14

The last public conversation between Hatsis and me was billed as “The Great Holy Mushroom Debate,” which took place as part of Breaking Convention 2019 at the University of Greenwich in London. The video (1:23:33) of this well-attended debate was posted on October 2, 2019, and has to date received 7,825 views.

In reading Hatsis’ Review, you may be perplexed by the personal animosity and sanctimonious sarcasm that runs through his tirade against The Psychedelic Gospels. If you are familiar with our book, you were most likely anticipating–as I was–that the most aggressive attacks on this hypothesis, which proposes that Christianity has a psychedelic history, would come from the Catholic Church, not from a “psychedelic historian.”

The source of Hatsis’ resentment is found in a temper tantrum he threw a few years ago. The Great Holy Mushroom Debate at Breaking Convention 2019 was the catalyst that triggered his hostility.

So, what happened?

As you can observe in the Debate video (from 45:52 to 46:46, and again from 56:34 to 58:07), I pointedly call Hatsis out and criticize him for grossly misrepresenting our work, based on his 2018 book Psychedelic Mystery Traditions (PMT) in which he specifically labels Julie and me as “discipuli Allegrae,” as “disciples of Allegro” (PMT, pp. 113–114).

Let’s look at what’s really going on here.

Hatsis main ploy for denying MICA is to set up (and then superciliously knockdown) a bogus straw man by classifying us, along with all researchers who support the “holy mushroom theory,” as “discipuli Allegrae,” which he defines as “a general term I use to refer to those who agree with the theories of John Marco Allegro, whose book The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross (1970) argued that Christianity evolved out of a magic mushroom-eating sex cult” (PMT, p. 108).

(As Latinist and psychedelic critic David Hewett has pointed out, Hatsis’ impromptu Latin term is wrong, as Allegro’s name should instead be Latinized in this case as Allegri. This is an example of Hatsis presenting himself as a knowledgeable expert yet making simple mistakes.)

Hatsis’ ploy is false and deliberately misleading because we unequivocally state in TPG that

“…our theory differs from Allegro’s in three fundamental ways. First, while Allegro denies the existence of Jesus, we agree with those scholars of religious studies who believe that Jesus was a historical figure. Second, while Allegro bases his theory on the speculative interpretation of ancient languages, we base our theory on the plausible identification of visual entheogenic images. Third, while Allegro hopes that his writings will liberate people from the thrall of a false Christian orthodoxy, we hope that our discoveries will educate people about the history of psychoactive sacraments in Christianity” (TPG, p. 217).

Off-camera at the debate, Hatsis became visibly agitated at being publicly chastised for blatantly distorting the truth. So agitated that shortly before our next planned debate, scheduled online for September 22, 2019, at The Mt. Tam Psilocybin Summit, Hatsis sent an unprofessional and threatening email to Daniel Shankin, the conference organizer, with a copy to me.

In this email, Hatsis accused me of being ignorant of medieval history and art, and threatened to take off the kid gloves and leave me and anyone who believed in this bullshit about MICA crying in a corner.

At that point, I withdrew from the debate and ended my relationship with Hatsis, stating that “I am a scholar, not a mud wrestler.”15 Obviously, Hatsis, who relishes playing the role of the critic, does not handle criticism well.

PLAINCOURAULT FRESCO IS AMANITA MUSCARIA

Transformation of Adam and Eve

The most well-preserved fresco in the Chapel of Plaincourault in central France is the Eden Scene from Genesis, depicting Adam and Eve and the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, around which a snake is coiled offering Eve the fruit of the Tree.

Chapel of Plaincourault, Plaincourault fresco, c. 1291

Photo by Julie M. Brown, enhanced for color and contrast

What is dramatic here is that the Tree is drawn in the shape of an enormous man-sized spotted mushroom, with four smaller spotted mushrooms protruding from the long stem of the central “mushroom tree.” To most scholars who study psychoactive mushrooms, the presence of numerous white spots on the caps of these five mushrooms strongly identifies them as Amanita muscaria.

Obviously, this is a stylized Amanita muscaria mushroom, and not a taxonomically precise image‒an obvious fact that somehow escapes Hatsis who in his Review makes much ado about the difference between an actual Amanita muscaria as found “in the natural world” and the image portrayed in this medieval fresco.

Hatsis also observes that “there is no such thing as a giant amanita muscaria; such a concept must be fabricated ad hoc in order to make a mushroom fit the bias.” Again, what Hatsis, who bills himself as an expert on medieval art, fails to recognize is that size matters in Romanesque art.

Given that this Plaincourault fresco belongs to a family of Romanesque wall paintings in central France that have been extensively catalogued by art historians, clearly the artist is emphasizing how significant this psychoactive mushroom is to the Eden story by painting an Amanita muscaria that is as tall as Adam and Eve.16

Upon close examination, Julie and I observed that there are two distinct moments depicted in the Plaincourault fresco: before and after eating of the forbidden fruit. The first “before” moment is the Temptation with the serpent offering the fruit to Eve. The second “after” moment shows the effect of eating the fruit, as Adam and Eve are “skeletonized” indicating they are entering an altered state of consciousness.17 Only a powerful psychoactive plant, in this case the Amanita muscaria mushroom, could occasion such a dramatic transformation (TPG, pp. 102-103).

In a nutshell, the essence of Hatsis’ Review of The Psychedelic Gospels is that: (1) “Plaincourault is the linchpin”‒is the sole sufficient image for evaluating the entire hypothesis of mushrooms in Christian art; (2) Plaincourault is not a psychoactive Amanita muscaria mushroom; (3) therefore, the entire hypothesis of MICA‒as documented by numerous expert researchers analyzing multiple medieval Christian works of art, from diverse European countries, spanning hundreds of years‒is, well, false!

Since Hatsis likes to sprinkle a Latin phrase here and there to give his writings a patina of erudition, I am sure he will not mind me doing the same. How about this one: reductio ad absurdum.

Distinguished Experts Identify the Fresco as Amanita Muscaria

Let us now contrast Hatsis’ credentials for drawing this “No” conclusion about the Plaincourault fresco with the credentials of eminent experts in the field who have concluded that “Yes” the Plaincourault fresco definitely is, or strongly resembles, an Amanita muscaria mushroom, and in doing so establish the consensus view.

No: Thomas Hatsis, who holds an M.A. degree in history, the discipline in which he claims authority; and who has never published his critiques of MICA in peer-reviewed academic journals where his work would be subject to review and approval by independent experts in the field.

Yes: Richard Evans Schultes, Ph.D., the father of modern ethnobotany, and Albert Hofmann, Ph.D., world-famous chemist who discovered LSD, who together write that “The Tree of Knowledge, entwined by the serpent, bears an uncanny resemblance to the Amanita muscaria mushroom.”18

Yes: Giorgio Samorini, ethnobotanist and ethnomycologist, who visited Plaincourault and published articles on the Plaincourault fresco and on “mushroom-trees,” classifying the Plaincourault fresco as the prototypical Amanita muscaria mushroom-tree.19

Yes: Carl A.P. Ruck, Ph.D., distinguished Classics Professor at Boston University, coauthor of The Road to Eleusis and of numerous publications describing the role of sacred mushrooms in Hellenic civilization, in early and medieval Christianity, and in the Renaissance, as well as in European fairy tales.

In The Hidden World: Survival of Shamanistic Themes in European Fairy Tales, Ruck and José Celdrán observe “…but the Tree is like no ordinary tree, for it is a giant specimen of Amanita muscaria.”20

Yes: Ervin Panofsky, Ph.D., eminent art historian. Yes, even Panofsky, who, based on his first letter of May 2, 1952, Wasson famously quotes as the ultimate authority for concluding that the Plaincourault fresco is not Amanita muscaria.

However, in a second letter to Wasson dated May 12, 1952, Panofsky backtracks and acknowledges that the Plaincourault could be “a real mushroom.”

We uncovered this second letter during our visit to the Wasson Archives at the Harvard University Herbarium in 2012 and published it side by side with Panofsky’s first letter to Wasson. See Figures 2 and 3 in our article on “Entheogens in Christian Art: Wasson, Allegro and the Psychedelic Gospels.”

This peer-reviewed article published in the Journal of Psychedelic Studies is particularly relevant to this Reply because:

- it extensively documents Hatsis’ duplicitous labelling of us as “disciples of Allegro,” the discredited and disgraced author of The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross, who argued that “Christianity evolved out of a magic mushroom-eating sex cult;”

- it provides direct confirmation by a JP Morgan Vice President that Wasson served as the “Pope’s banker;” and

- it proves that Panofsky admitted that the Plaincourault fresco could, after all, be “a real mushroom.”

So, there you have it. According to distinguished experts, the Plaincourault fresco is an Amanita muscaria mushroom.

ADVANCING THE STUDY OF MUSHROOMS IN CHRISTIANITY

Allegro is Completely Irrelevant to the Topic

Hatsis repeatedly attempts to narrow and tie the discussion of mushrooms in Christian art to John Marco Allegro’s book, The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross, originally published in London in 1970, and its “discovery” of a “secret amanita cult.”

Here, Hatsis is ploughing fertile ground in popular culture because for many people in the psychedelic community the mere mention of MICA brings Allegro and The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross to mind.

As a matter of fact, Allegro’s book is completely irrelevant to the study of mushrooms in Christian art. Allegro’s book is a work of philology, not of art history or interpretation.

In The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross, Allegro proposes that the earliest Christians used etymological punning and other linguistic techniques to conceal their secret use of the Amanita muscaria in service to a religion focused on fertility, with the mushroom as a potent symbol of sexuality and procreation.

In the original edition of his 253-page book, Allegro mentions the Plaincourault fresco once, and only once, on page 80. Here, Allegro merely reports that others have identified that the tree is depicted as a mushroom.

Aside from this, Allegro’s book is dedicated exclusively to etymology, the study of the origin of words, tracing the roots of Mediterranean languages back to Sumerian with a particular focus on concepts of fertility.

Allegro has nothing original to say about mushrooms in Christian art. He does not produce any new evidence, interpretations, or theories about Christian art.

Nevertheless, to preserve his straw man argument, Hatsis needs to keep the topic of mushrooms in Christian art focused on Allegro and the idea of a secret Christian amanita cult. As a result, anytime someone mentions “mushrooms in Christianity,” Hatsis automatically hears “Allegro” and feels called to step in as the self-appointed debunker. In reality, Hatsis is debunking a ghost.

To advance the study of mushrooms in Christian art, it is time to bury the ghost of John Marco Allegro, which has for the past half-century cast a long shadow over the field.

Revitalizing the Study of Mushrooms in Christianity

I disagree with Allegro’ and Hatsis’ shared focus on secrecy and on amanita. We must move beyond both Allegro, the advocate of a secret Christian amanita cult, and Hatsis, the debunker of a secret Christian amanita cult.

Instead, I call for students of psychedelics in world religions to expand their focus in the study of MICA to include Psilocybe-variety mushrooms along with Amanita muscaria, and to consider other scenarios for the extent of mushroom use in Christian history besides the narrow idea of a secret cult.

As researcher David Hewett points out, until now many scholars in the field have taken it for granted that mushroom use was secret, known only to a few, and always hidden. In The Immorality Key, author Brian Muraresku goes even further and argues that the use of psychedelics was suppressed under the “jackboots of the Catholic Church” as early as the fourth century. The field must stop limiting itself to such an overly narrow scenario for mushrooms in Christianity.

At this point, the central question for the field should be: to what extent are psychoactive mushrooms present in Christian history?

Based on the extensive iconic evidence for psychoactive mushrooms in medieval European churches, we must consider and evaluate several scenarios including:

- Secret use by marginal figures and groups who face oppression, such as heretics and witches.

- Clandestine use by ecclesiastical elite and initiates, who encode esoteric messages in art and text.

- Widespread open use by many groups and figures to whom the “mystery” has been revealed.

Systematically investigating this question is the most important agenda for the field. This agenda includes researching, analyzing, and reporting on mushrooms in Christian art and in Christian texts, over a wide geographic area including the Middle East as well as Europe, and over a time frame that spans early Christianity, medieval Christianity, and the Renaissance.

Given the growing evidence for mushrooms in Christianity documented by multiple scholars, the field would benefit from a good literature review to take current stock of its achievements and limitations.

Likewise, the field needs more galleries of Christian art with quality images, such as those found in Gosso and Camilla’s Allucinogeni e Cristianesimo: Evidenze nell’arte sacra (Italian: Hallucinogens and Christianity: Evidence in Sacred Art). Michael Hoffman has produced an extensive web gallery of mushrooms in Christian art.

Mushroom images in art: The field is also in need of robust categories for classifying depictions of mushrooms in art.

For example, Samorini proposes a two-fold typology of mushroom trees, using the Plaincourault Amanita muscaria and the Saint Savin psilocybin mushroom as ideal types.21

Researcher Michael Hoffman defines three categories for classifying mushroom images: literal depictions of mushrooms, stylized depictions of mushrooms, and depictions of mushroom effects which suggest altered states of consciousness.

I find Hoffman’s categories useful for classifying the two varieties of MICA that we photographed at the following religious sites. The text in parentheses indicates the black and white Figure (Fig.) or color Plate (P) in The Psychedelic Gospels that displays our photographs of these images.

Type of Evidence |

Amanita muscaria |

Psilocbye varieties |

| Literal – taxonomically accurate images | Rosslyn Chapel, Scotland (Fig. 1.1)22 | St. Michael’s Church, Germany (Fig. 11.2)23 |

| Stylized – mushroom-like shapes | Great Canterbury Psalter, England (P12) | Church of St. Martin de Vicq, France (P6) |

| ASC – images suggesting altered states of consciousness | Chapel of Plaincourault, France (P5) | Chartres Cathedral, France (P18) |

Mushroom references in texts: The field also needs a database of textual references to mushrooms in Christian history. Hatsis claims that there are no textual references to mushrooms among Christian theologians.

This can only be a bluff on Hatsis’ part since the research entailed in reading all ancient and medieval Christian theologians would take years.

Ironically, in response to Hatsis’ question “So then where is the written evidence?” it is worth noting that Hatsis himself provides a powerful rationale explaining why early Christians throughout the Roman Empire would refrain from writing about their psychedelic mushroom experiences or about the possible role of “pharmaka” (Hatsis’ preferred term for “drugs”) in the original Eucharist.

In Psychedelic Mystery Traditions, Hatsis tells us that “An accusation of magic, expressly forbidden in Rome, could have landed Jesus in prison, his disciples mocked as followers of a criminal. Why would the gospel authors have written about Jesus’s use of pharmaka? Such a thing could get a person crucified…” (PMT, p. 125).

To realize the ambitious research agenda outlined above, in the Appendix to our book we call for the formation of an Interdisciplinary Committee on the Psychedelic Gospels (TPG, pp. 222-228).

Christianity and the Psychedelic Renaissance

It is time for the study of psychoactive mushrooms in Christianity to fulfill its promise. It is an area of research that has the potential to revolutionize our understanding of the history of Christianity, as well as the ability to influence the future of psychedelics.

In concluding I would like to briefly mention three reasons why documenting the historical presence of mushrooms in Christian art could be relevant to the Psychedelic Renaissance.

First, it may in time provide the catalyst for the Catholic Church’s return to its mystical roots involving direct entheogenic experience of the divine.

Second, it may open the door for the establishment of religious retreat centers, the “modern Eleusis” that Albert Hofmann envisioned, where the Church would offer the faithful safe psychedelic journeys for healing and revelation in the presence of trained guides.

Third, it may meet the “bona fide traditional ceremony purposes” requirement specified in the federal 1993 Religious Freedom Reform Act, thereby establishing the basis for the legalization of the religious use of psychoactive mushrooms as a First Amendment right.

This would be similar to the right to integrate psychedelics into religious ceremonies currently granted to members of the Native American Church who use peyote, and to members of several U.S. branches of the Brazilian churches of Santo Daime and União do Vegetal who use DMT-containing ayahuasca in religious ceremonies.

REFERENCES

2 Carl A.P. Ruck, personal communication, December 28, 2021. Hatsis’ misinterpretation of the Regensburg Sacramentary was initially called to my attention by David Hewett, M.A., who teaches ancient Greek and Latin at The Paideia Institute for Humanistic Study and writes about psychedelics in literature and art at cyberdisciple.wordpress.com. Hewett points out that there is an alternative possible translation which would indicate that, instead of taking up the lance, the angel is placing the lance in the ruler’s hand. However, this would not alter Hatsis’ misinterpretation of the image.

3 Ruck, personal communication, December 28, 2021.

4 See Howard L. Adelson, The Holy Lance and the Hereditary German Monarchy, The Art Bulletin 48, no. 2 (1966): 177–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/3048362.

5 For the date of Henry II’s coronation and other information on the Sacramentary of Henry II, see the U.S. Library of Congress description of this illuminated manuscript here.

6 One would expect JStor, a database of major academic journals, to give some results when searching for “parasol of victory” (search result here). Jstor turns up 44 results when searched for “paradiesbaum” (search result here). Moreover, journals dedicated to reviewing academic books in the fields of Classical Studies and Medieval Studies return no relevant results when searched for the same terms (Bryn Mawr Classical Review search for “parasol of victory”; search The Medieval Review here (results cannot be linked to).

7 See Jerry B. Brown and Matthew Lupu, Sacred plants and the gnostic church: Speculation on entheogen use in early Christian ritual, Journal of Ancient History, 2014, 2(1), 64–77.

8 In Psychedelic Mystery Traditions, Hatsis identifies three groups that practiced Christian psychedelic mysteries: Nazarenes, pagan Neoplatonists and early Orthodox traditions, 2018, pp. 106-108.

9 Judith Anne Brown, John Marco Allegro: The Maverick of the Dead Sea Scrolls 2005. See chapter 11, Questioning The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross, and chapter 12, Following The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross. Judith Anne Brown, the author of this biography, is Allegro’s daughter.

10 R. Gordon Wasson, letter to Times Literary Supplement, September 25, 1970.

11 This acrimonious controversy is documented by Jan Irvin in The Holy Mushroom: Evidence of Mushrooms in Judeo-Christianity, 2008; and is summarized in chapter 7, “The Battle of the Trees,” in Jerry B. Brown and Julie M. Brown, The Psychedelic Gospels: The Secret History of Hallucinogens in Christianity, 2016.

12 Without commenting on the relative quality of their work, the list of contemporary researchers includes James Arthur, David Spess, Jonathan Ott, Dan Russell, Mark Hoffman, Carl Ruck, Blaise Staples, Clark Heinrich, Jan Irvin, John Rush, Peter Furst, Huston Smith, Jack Herer, Robert Thorne, José Alfredo Gonzàlez Celdràn, Michael Hoffman, Fulvio Gosso and Gilberto Camilla.

13 Mitchell Kaplan, past president of the American Booksellers Association, describes The Psychedelic Gospels as “Part travelogue, part anthropological meditation, and part groundbreaking study showing the use of sacred mushrooms in Christian iconography…” Don Lattin, bestselling author of The Harvard Psychedelic Club says “It’s The Da Vinci Code meets The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.”

14 In this documentary, Hatsis’ and my views are interwoven with a history of the holy mushroom theory, along with commentary by Chris Bennett, Roland Griffiths, and Dennis McKenna, among others. Viewers must subscribe to Gaia TV to watch this documentary, which is part of an original, two-season, 22-episode “Psychedelica” series.

15 Shortly after this email, Hatsis initially apologized but then immediately issued another threat, at which point I definitively withdrew from this debate. The conference organizer allowed Hatsis and me to make separate presentations.

16 Marcia Kupfer, Romanesque Wall Painting in Central France: The Politics of Narrative, 1993.

17 In chapter 7, Battle of the Trees, we write: “I knew that anthropologist Peter Furst points out that one of the most enduring aspects of shamanism is the idea that life is resident in the bones, which are the most durable part of the body, lasting up to 50,000 years after death. Mircea Eliade, one of the world’s greatest authorities on shamanism, writes that ‘Bone represents the very source of life, both in humans and animals. To reduce oneself to the skeleton condition is equivalent to re-entering the womb of this primordial life, that is, to a complete renewal, mystical rebirth’” (TPG, p. 102).

18 R. E. Schultes and A. Hofmann, Plants of the Gods: Origins of Hallucinogen Use, 1979, p. 83.

19 Giorgio Samorini, The mushroom-tree of Plaincourault, Eleusis, 1997, 8, 30–37; and “Mushroom-trees” in Christian art, Eleusis, 1998, 1, 87–108.

20 Carl A.P. Ruck, Blaise Daniel Staples, et. al., The Hidden World: Survival of Pagan Shamanic Themes in Europe Fairy Tales, 2007, p. 349.

21 Giorgio Samorini, Mushroom-trees in Christian art, Eleusis: Journal of Psychoactive Plants and Compounds, 1998, 1: 87-108.

22 On August 22, 2015, while we were writing The Psychedelic Gospels Julie and I met Paul Stamets, one of the world’s leading experts on mycology. Stamets had personally visited Rosslyn and confirmed that the mushroom we found in the Green Man’s forehead was a “taxonomically correct Amanita muscaria.”

23 Giorgio Samorini, Mushroom-trees in Christian art, Eleusis: Journal of Psychoactive Plants and Compounds, 1998, 1:87-108, notes that the depiction “seems to indicate quite clearly that the artist intended to represent this species of mushroom in his bas-relief” (p. 103). Furthermore, “As ethnobotanist Giorgio Samorini observes, ‘The mushroom-tree is realistically rendered with a precision not far short of anatomical accuracy and can be identified as one of the most common Germanic and European psilocybian mushroom, P. semilanceata’,” as cited in Jerry B. Brown and Julie M. Brown, The Psychedelic Gospels, 2016, p. 156.

Did you know? Mushrooms are not the only psychedelic plant out there

Yes, having taught a course on “Psychedelics and Culture” since 1975, I am aware that there are many psychedelic plants and fungi beyond mushrooms, including but surely not limited to the DMT-containing shrub Psychotria viridis used to make ayahuasca in the Amazon, the mescaline-containing peyote used by the Huichol and Cora of Mexico, and the ibogaine-containing Tabernanthe iboga used by the Fang people of Gabon.

It is very possible that the tree canopy in the Plaincourault fresco – and the same strangely shaped ‘trees’ seen on some of the stained-glass windows of Chartres – have their ultimate source in a pair of Sumerian pictograms/words which together had the meaning ‘shade’ and which appeared during the earliest period of writing in the 4th millennium BCE. Allegro mentioned this meaning in The Sacred Mushroom And The Cross. In my own recently published book, Lost Stones Of The Anunnaki, I provide a good deal of evidence for references to hallucinogenic substances in pre-Christian Sumero-Akkadian texts. The source of the Greek name amanita is also found in the Mesopotamian tablets (https://grahamhancock.com/dainesm5/). If John Marco Allegro had been in possession of a computer, there is little doubt he would have discovered it long before me.

What he didn’t know is that one of the two original pictograms of ‘shade’ looks for all the world like a mushroom cap with short dashes that might or might not represent amanita muscaria spots. It sits next to the word for ‘tree’. I argue that their meaning goes beyond the simplistic notion of a tree with a protective canopy of branches and leaves. It is considerably more subtle. This is the source word for Greek ‘mycelium’, fungi that communicate underground, feeding off tree roots while providing nourishment for the forest. Although my own study is based in texts from thousands of years earlier, that word provides convincing visual evidence for a linguistic precedent to versions seen on medieval church walls and windows. John Marco Allegro was not so far off the mark after all.

The windows of the Cathedral at Chartres include a scene in which the biblical prophet Jonah is being vomited onto dry land by the whale. That scene has a series of ‘mushroom trees’ in the foreground and, although the window is not mentioned in my book (I hadn’t seen it at the time), I did make the case for Mesopotamian Jonah sitting in the shade of a hallucinatory plant – one that was conjured up by God. While it might be reasoned that the tree between Adam and Eve is just that – a tree – as in the biblical story, it is considerably less obvious why at Chartres the story of Jonah and the Whale would include a row of them.

As for the parasol argument put forward by Tom Hatsis, it has always represented protection for obvious reasons. Did images of it hark back to a more ancient story of victory over death? After all, that’s what the discussion is about; the use of mind-altering substances to experience death and to return to life. Referring to victory would signify that the so-called parasol of victory (if it does have a long history as such) would rather be an argument in favour of the even more ancient mushroom tree concept. Then again, it’s my contention that both ‘umbrella’ and ‘umbilical’ have their source in Sumerian UM, the ‘cord’, that of UM-MA, the ancestral mother.

NAR, the renard and trickster, used by Tom Hatsis in his reasoning also appears in Sumerian texts. The Sumerian fox is a musician, guilty of deliberately lulling… definitely nar-cotic (yet another word of unknown origin beyond the Greeks). Again, the presence of a trickster fox at Plaincourault does nothing to negate the existence of a mushroom tree unless the ultimate source and true underlying meaning of that story are known for sure.

The meanings mentioned here are all derived from orthodox dictionary meanings – nothing fanciful. Can the Mesopotamian evidence be useful in an argument over medieval mushroom trees? Perhaps not but intriguing similarities nevertheless.

Madeleine – Thank you for these intriguing and perceptive observations, which have among other things inspired me to read your book. In my wife/coauthor Julie and my article on “Entheogens in Christian Art: Wasson, Allegro and the Psychedelic Gospels,” we make the following observations about the St. Eustace window in Chartres Cathedral:

“Among the cathedral’s 176 stained glass windows, we documented at least 13 Old and New Testament stories showing mushroom images, including several stories related to the life of Jesus. The Old Testament stories include the Zodiac Window, showing the cycle of the “labors of the months,” along with the stories of Adam and Eve and of Joseph and Noah.

The Saint Eustace window is representative of these New Testament stories (Figure 13). The opening panels of this window show Placidas (the future Saint Eustace) hunting stag on horseback, surrounded by hunting horns, huntsmen and hounds. In the next panel, we see the Conversion of Placidas to Saint Eustace. Flanked by sacred mushrooms, he kneels and prays before the crucifix, which appears between the antlers of a stag standing regally before him. This parallels Samorini’s (1998, pp. 89–90) description of the pre-Christian 5th century BCE Tunisian mosaic where the mushroom tree stands between two deer. Here, in the medieval Christian era, the Cross has replaced the mushroom tree.”

For the Samorini references, see: Samorini, G. (1998). “Mushroom-trees” in Christian art. Eleusis, 1, 87–108.

For our full article in the Journal of Psychedelic Studies, see: https://akjournals.com/view/journals/2054/3/2/article-p142.xml

Regarding your observations about the “evidence for references to hallucinogenic substances in pre-Christian Sumero-Akkadian texts,” as you probably know Wasson devoted an entire section of Soma: Divine Mushroom of Immortality to tracing the etymological roots of the words for “mushroom’ in several reindeer herder and other linguistic groups.

If you’d like to continue this conversation, I invite you to write me at: [email protected]

To elaborate on Wasson’s research, following page 166 in SOMA (1968), he provides a chart of Pon Cluster root words in Uralic language groups dating from 4000 BC, which branch off into Samoyed and Finno-Ugrian around 1500 BC or earlier. Pon root words include: to be inebriated, drum, fly agaric, made mushroom, mushroom and to lose consciousness. Furthermore, section B of the Exhibits to SOMA cites or paraphrases various sources on “The Linguistic Aspect” of words used for mushrooms, or specifically for fly-agaric.

Unfortunately for Wasson’s linguistic theories, there is no evidence whatsoever from 4000 BC other than the Sumerian writings. However, as I have laid out as clearly as possible in Lost Stones, there is extremely solid evidence in both the lexical tablets and in the earliest literary text (which I translated and published in 2017) for Sumerian MUSH, which has the given meaning ‘snake’, as source of our word ‘mushroom’. It doesn’t get more straightforward than that. It explains the biblical link between tree and snake in Genesis (another word stemming directly from Sumerian) and even takes in the name Jesus, giving some credence to John Allegro’s much shunned observations. The source of ‘agaric’ is also explored in Lost Stones. Sumerian has always been ignored (and now me with it…) as a potential etymological source for the simple reason that it was once declared an isolated language. By ignored, I mean not even discussed as a possibility. That is the barrier that very few contemplate climbing over – a statement made in modern times by the first translators of this previously unknown language. And yet the evidence put forward in three books now is overwhelming, all of it directly substantiated by the tablets, thoroughly referenced. No other suggested source for these words comes anywhere close. They match in both meaning and sound, and in some cases even visually as you will see if you read Lost Stones. I will be happy to discuss them all with you in depth.

Kind regards,

Madeleine

If some Christian artworks have ‘stylised mushrooms’, how could you tell they were not stylised festive trees? And then some Christian art should have anatomically correct mushrooms?

Were the umbrella-shaped trees on the Azores or Canary Islands perhaps a model in Christian art? They have red sap as I recall.

If an umbrella image symbol came from India, should there be other Indian symbols as well? Such as the milky ocean churn?

Given the tradition of herbal books in the Middle Ages, do any of them deal with mushrooms? Or picture stylised mushrooms?

As disucssed in chapter 7 the “Battle of the Trees” of our book The Psychedelic Gospels, to identify stylized mushrooms or mushroom-trees we use the iconology method advocated by art historian Erwin Panofsky, which Wikipedia describes as follows:

In Studies in Iconology Panofsky details his idea of three levels of art-historical understanding:

Primary or natural subject matter: The most basic level of understanding, this stratum consists of perception of the work’s pure form. Take, for example, a painting of the Last Supper. If we stopped at this first stratum, such a picture could only be perceived as a painting of 13 men seated at a table. This first level is the most basic understanding of a work, devoid of any added cultural knowledge.

Secondary or conventional subject matter (iconography): This stratum goes a step further and brings to the equation cultural and iconographic knowledge. For example, a Western viewer would understand that the painting of 13 men around a table would represent the Last Supper. Similarly, a representation of a haloed man with a lion could be interpreted as a depiction of St. Mark.

Tertiary or intrinsic meaning or content (iconology): This level takes into account personal, technical, and cultural history into the understanding of a work. It looks at art not as an isolated incident, but as the product of a historical environment. Working in this stratum, the art historian can ask questions like “why did the artist choose to represent The Last Supper in this way?” or “Why was St. Mark such an important saint to the patron of this work?” Essentially, this last stratum is a synthesis; it is the art historian asking “what does it all mean?”

Panofsky’s proposed three levels of meaning in art (representation or objective, conventional iconography or cultural ethnography, and ‘historic’ contex), does not have any theoretical framework, except for the general, common sense, and unscientific assumptions that artists consciously choose images; to illustrate certain myths; and represents a polity of a certain time and place. This is the kind of art history that should be torn out of textbooks (as the fictional teacher in the movie Dead Poets Society instructs his learners to do).

Other art historians emphasise styling, which is inherently meaningless, except for purposes of appropriation. Others emphasise diffusion (Witzel etc), which also lacks theory and assumes culture to be as conscious, cumulative, developing, and ‘evolving’ construct. I have criticised Witzel’s ridiculous assumptions and conclusions elsewhere in this phorum. And criticised Lewis-Williams’ over-emphasis on ‘ethnography’ (myth) in both my books. And criticised the academic assumptions of the human sciences in a chapter on popular anthropology, titled ‘Broken telephone’, in my book Stoneprint (2016).

Your academic, but unscientific sources, and you, fail to take account of the role of subconscious behaviour, and its access to archetypal structure, in cultural media.

My conscious criticism of your work is that you cannot see the trees for the mushrooms. Your ‘mushrooms’ outnumber your trees, while in cultural media trees, including the occasional entheogens, far outnumber mushrooms. Old and new Testaments make much of trees, from Eden to family trees to staffs to the cross. Perhaps most of the ‘mushroom’ bushes in art are actually alchemical blends of trance vision textures and herbal signatures, mainly of grapevines and entheogenic additives, some of which may include mushrooms.

Since you discuss some rose windows above, here is an example of the Tree of Jesse in a rose window, including a demonstration of the standard, global, subconscious re-expression of archetypal structure in that design (which appears in all complex artworks of all styles and supposedly ‘different cultures’ worldwide, thus there is only one culture. My evidence contradicts the supposed ‘contexts’ as am ‘idiosyncratic framework’ for artworks, and demonstrates that the collective human condition is a readable framework: https://edmondfurter.wordpress.com/2020/04/12/archetypes-in-paris-notre-dame-portals-windows-and-floor-plan/

Trees are certainly important images, with key metaphorical meaning. If I’m reading you right, you fear that Brown and others want to erase trees for mushrooms or otherwise ignore the importance of tree as symbol. I don’t believe that’s the case, however, and mistakes Brown for arguing that the images depict mushrooms *and not* trees. Rather, the image displays in some way both a tree and a mushroom, multiple referents at the same time, without one necessarily eclipsing the other.

Ultimately, this is a matter of modes of viewing, less of absolute identification. In an article from last September about Hatsis’ earlier criticisms of seeing mushrooms in art, I wrote “Pre-modern art is widely recognized as a multi-valent, multi-layered system of figural allusion. Objects in pre-modern art are not merely representations of just one thing, but exist in a system of allusions, whether to other versions of the same image, to related images, across media (e.g. visual allusions to literary text and vice versa; or to ritual action), or to models imagined to exist at a higher metaphysical level…. This multi-valency of art, literary text, and ritual is in fact even more interesting and apt with regard to psychedelics, because of the well-known allusive and metaphorical state of consciousness induced by psychedelics; a playful overlapping of representations is perfectly in line with the psychedelic experience. For example, it is perfectly reasonable to expect that artists familiar with the effects of psychedelics would depict mushrooms as trees and trees as mushrooms.”

From: https://cyberdisciple.wordpress.com/tag/thomas-hatsis/#art-interpretation

I generally agree with you. Except that art still contains all the things it had always done (several functions, core content, styling, texture, etc). And except that sober artists do the same as tripping artists, the difference usually only in signature textures, which are inherently meaningless. I have three articles about the roles of drugs in Oracles of the Dead. And several about various drugs textures, here is one relevant to peyote cactus: https://mindprintart.wordpress.com/2016/10/02/peyote-or-mescaline-art/

Mr. Brown, please take a look at:

https://metahistory.org/Discovery.php

Thank you. I am familar with this article. Unfortunately, the author confuses The Great Canterbury Psalter (GCP) – which opens with the images (illuminated minatures) shown at the beginning of the article – with the name Eadwine Psalter. The image in the article is an extremely poor copy of a portion of the opening folio of the GCP, possibly due to the author’s being only able to view it on microfiche. As described in the chapter on “Canterbury Tales” in our book The Psychedelic Gospels, the original GCP is housed in the French National Library in Paris; however a Spanish publishing house specializing medieval manuscripts published several hundred exact replicas of the original GCP, a copy of which we were able to view and photograph at the Cambridge University Library in England. Color plate 13 in our book presents a color image of folio 1, Genesis, GCP, which includes the illumination of “God Creates Plants” shown in plate 12 of our book, reprinted courtesy of the Bibliotheque nationale de France, Paris.

Hi friends!

Posting the correct address for our 2019 Psilocybin Summit here:

https://circle.tamintegration.com/courses/2019-psilocybin-summit/

Thank You!

Thanks for this program link, which lists my Sunday presentation on

“Entheogens in Christian Art: Wasson, Allegro and the Psychedelic Gospels with Jerry Brown”

… the Boat of Ra arrived at the town of Het-Aha; its forepart was made of palm wood, and the hind part was made of acacia wood; thus the palm tree and the acacia tree have been sacred trees from that day to this.

—the Legend of Horus of Behutet and the Winged Disk

Acacia’s sweet smelling, yellow flowers, which look like little yellow sunbursts, are astringent and were used to help cleanse the skin and clear up skin problems. Brewed acacia leaves were drunk in a cough mixture. They were also applied to wounds and swollen limbs for their astringent properties. The tree’s seedpods are edible by livestock. The crushed bark produces tannin that was used to help heal burns and tan leather.

https://isiopolis.com/2015/07/12/isis-the-acacia-goddess/

There is a discussion of “Entheogenic Egypt” on pages 209-211 of The Psychedelic Gospels, which states that “…there is also evidence of knowldge of psychoactive fungi and of the acacia tree, one of the most prominent trees in ancient Egyptian art due to its association with the death and rebrith of the god Osiris” (p. 211). Color plates 27 (datura flowers) and 28 (Amanita muscaria) show other entheogens depicted in ancient Egyptian art.

Thanks Jerry

I realize everyone needs to pick their own battles, but Im not sensing any forward motion on actual “psychedelic history” resulting from this little “debate” or whatever you wish to call it

But then again, its your business to handle as you see fit

Enjoy!

Hi Josh, as I state at the beginning of my article, I did not initiate this current debate – in fact had stopped debating Tom Hatsis back in 2019. But faced with the fait accompli of Hatsis’ vituperative critique of our book being posted on Graham Hancock’s popular website, I felt a responsbility to our research and readers to write this reply. Sometimes in life you do not get to pick your battles – as the Ukranians are painfully learning. ~ Jerry B. Brown

Thanks, Jerry – essentially it is your business, not mine – and I don’t presume to know the full scope of your efforts in all of this

Im just a casual observer offering my personal opinion on the exchange presented on this website

Donald Trump is Jesus Christ. America will be debt free. We will return to God’s Country. Many have been robbed of their common sense. No man can bring down each country’s wealth, Royals, and clear the massive number of tunnels from the satanic killings of so many children but Jesus Christ. It is common sense. Donald Trump did this. EVERYTHING YOU THINK YOU KNOW ARE LIES FOR DECADES MANY MEGA CHURCHES FUNDED BY SOROS TO CONTROL YOU.

I’m sorry but Donald Trump is not Jesus Christ.

MASKS ARE A SYMBOL OF TYRANNY