It is our pleasure to welcome chemical pharmacologist and neurobiologist Dr Andrew R. Gallimore, author of Reality Switch Technologies: Psychedelics as Tools for the Discovery and Exploration of New Worlds, as our featured author for February. His book explains in unprecedented depth and detail how psychedelic molecules interact with the human brain, alter the structure and dynamics of the subjective world, and rapidly and efficiently switch the brain’s reality channel, opening up a vast number of alternate worlds for discovery and exploration. In his article here, Andrew shines a light on the inner landscapes of the brain and how psychedelics can dramatically alter these landscapes, transforming our experience of the world.

Interact with Andrew on our AoM Forum here.

“You are in possession of an exquisite machine motionlessly buoyant in the softly circulating fluids of your skull. A world-building machine. And psychedelic molecules are the tools for tuning and operating this machine.” Reality Switch Technologies

When I first heard about DMT as a teenager, this astonishing 15-minute psychedelic that could literally transport you to a bizarre hyperdimensional reality teeming with giggling elf-like beings that would dance and sing impossible objects into existence, I’m not sure I really believed it. DMT is like that — it’s hard to take seriously, or at least to understand why people are so keen to rant and rave about it. Until, that is, you get a chance experience it yourself. Terence McKenna often said that there’s only one sure-fire convincer when it comes to DMT: a small glass pipe and a few minutes of your time. And, indeed, within just a few seconds of my very first acrid lungful of DMT vapour a couple of decades ago, I knew without any doubt that this molecule was most certainly to be taken very very seriously. In that instant, unbidden and thoroughly unanticipated,I was confronted with the presence of an intelligence that I had hitherto neither suspected existed nor had any way of predicting could exist. Its immensity, immediacy, and absolute undeniability shocked and horrified me. There was no turning back for me from this point. There was no unseeing what I’d seen. I laid on my bed shaking to my very bones having just discovered — for myself at least — a new world entire. And not just any old new world, but the strangest world I couldn’t possibly have imagined, even with the benefit of the best part of a decade of Terence McKenna lectures under my belt.

In the two decades since that night, having decided to devote my life to this molecule and others like it, I’ve come to appreciate that the DMT world, bizarre and frankly miraculous as it is, is but one amongst countless others, the vast majority of which no human has ever imagined, let alone visited. And, what’s more remarkable is that all of these worlds – or “reality channels” – are accessible to each of us, if only we can find the right keys. In my latest book, Reality Switch Technologies: Psychedelics as Tools for the Discovery and Exploration of New Worlds, I explain in unprecedented depth and detail how these “reality channel switches”, operated by psychedelic molecules procured from the environment or synthesised in the laboratory, grant us access to these normally hidden worlds.

Being immersed in a world is a fundamental part of what it means to be human: whether you’re awake, dreaming, or at the peak of a DMT trip, there is always a world — both inner and outer— in every direction. Of course, the extremely bizarre DMT worlds bear no resemblance to the normal waking world1, whereas the dream world is usually much more familiar2. And, indeed, there are other types of worlds that can be experienced: the fragmented worlds of a schizophrenic patient or the utterly ridiculous and often horrifying worlds visited with concentrated Salvia divinorum extracts3. And, beyond even these, endless worlds which we might one day, perhaps in the not too distant future, learn to reach and explore.

The most familiar of experienced worlds, the world of everyday waking life is, in modern scientific parlance, a model of the environment built by the brain. The purpose of this model is to provide you with what philosopher Thomas Metzinger calls a “simulational space”4 that you can use to navigate and interact with your environment. Obviously, there is a relationship — a mapping — between the model and the environment itself, but the world you experience is always this model. When you smoke a sufficient dose of DMT, what changes — in a shockingly dramatic manner — is this model constructed by your brain. The normal waking world model is obliterated and the brain begins constructing an entirely novel world thoroughly unlike it. The same applies to other psychedelics, such as the reality-shattering salvinorin or the lesser explored tropane alkaloids from Datura and the Old-World witching herbs, such as mandrake and henbane5. All psychedelics, each in their own way, alter the structure and dynamics of your world model.

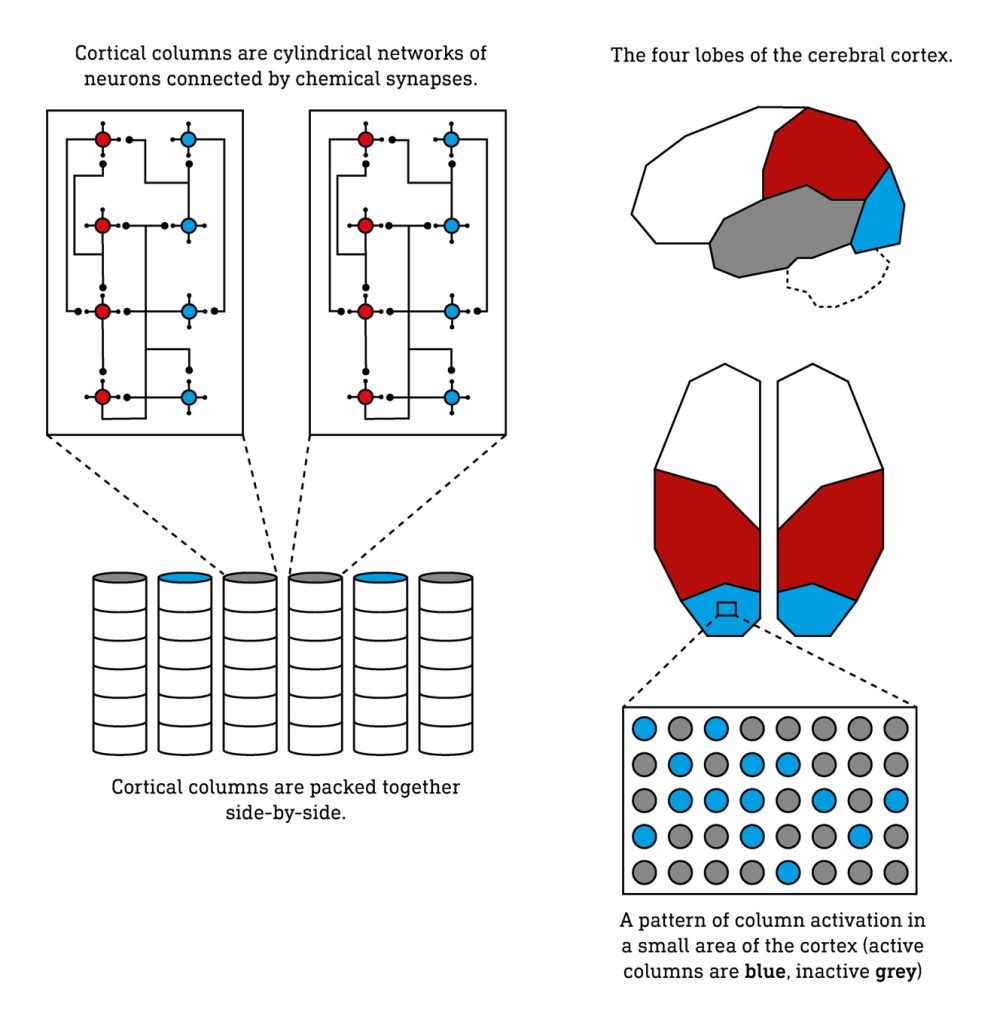

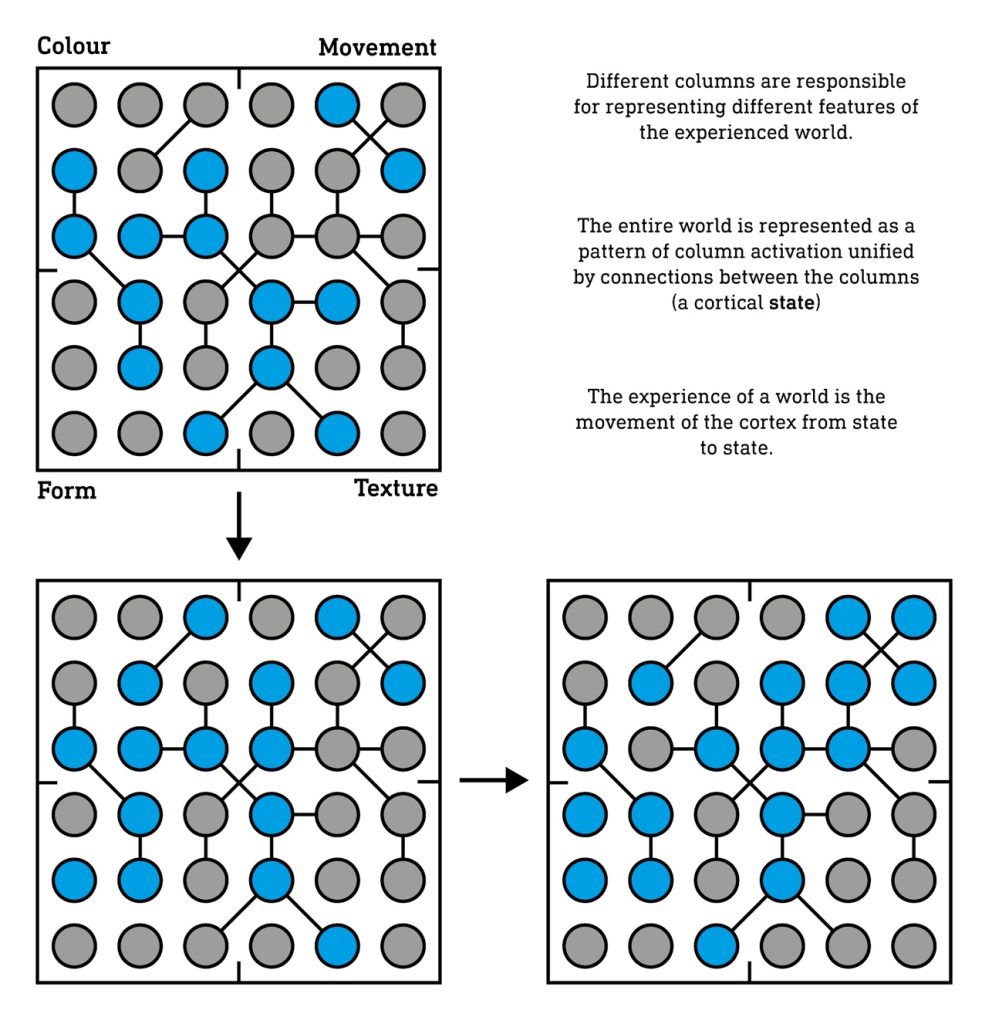

The outer layer of the brain — known as the cerebral cortex — is responsible for building this world model and is essentially a folded sheet containing billions of interconnected neurons, the major information-generating cells of the brain. Closely connected groups of neurons form cylindrical cortical columns specialised — tuned — to receive, process, and generate particular types of information that correspond to particular features of your experienced world, such as lines, colours, textures, spatial relationships, and specific types of objects6. These cortical columns are connected, using chemical connections called synapses, to form networks that control the structure and flow of information through the brain, allowing it to “sculpt” its model of the world7.

By modifying these patterns of connections, throughout the course of evolution, development, and by the constant sampling of sensory information from the environment, the brain improves and refines this model8. The world you experience from moment to moment is the highly complex and dynamic pattern of information generated by these networks of cortical columns. Or, equivalently, your phenomenal world is what this pattern of information feels like from your subjective perspective. Your world is built from information.

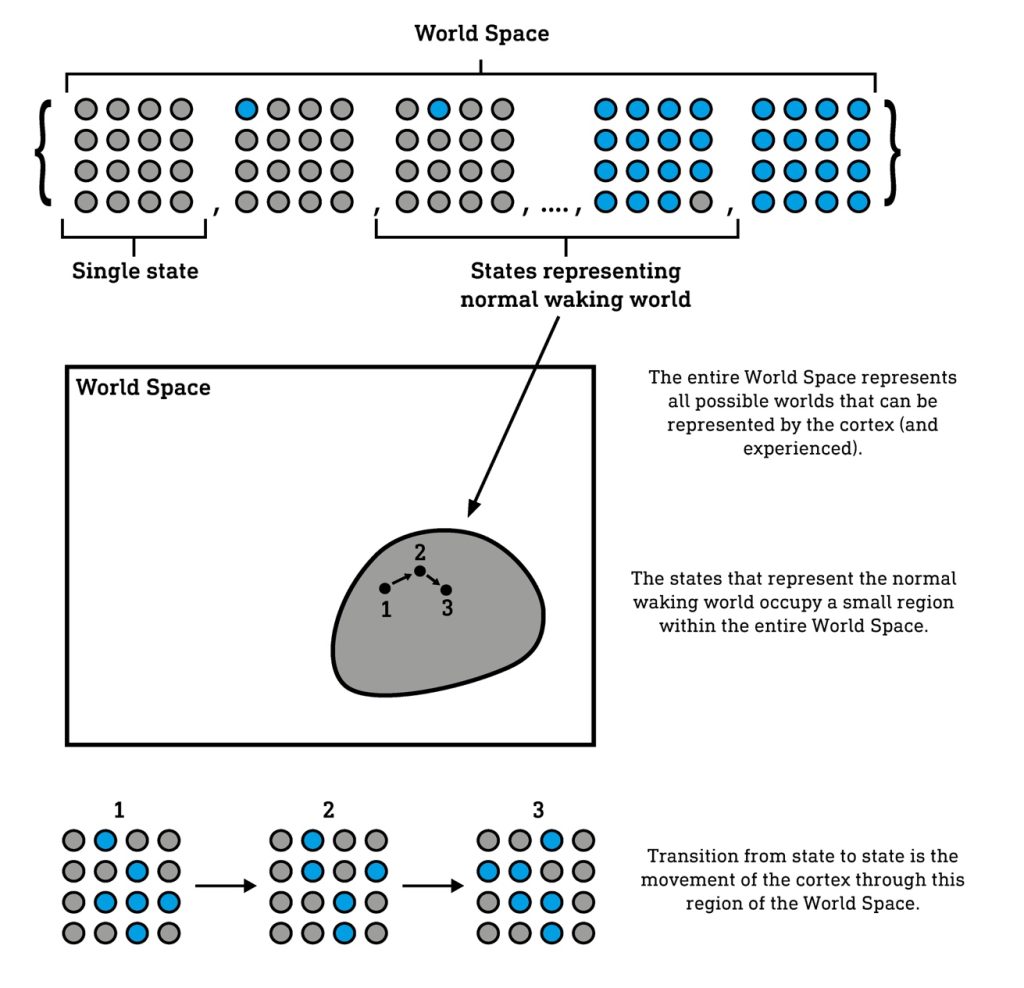

If we could freeze time and measure the activity in every cortical column responsible for constructing your world, we would find a unique pattern of column activation — a pattern of information — that represented your entire world at that moment and your experience of this world is the flow of your cortex from one unified pattern of column activation to the next. This applies to all experienced worlds, both strange and familiar. And so, in a sense, all experienced worlds are equally real in that all are built from patterns of neural information.

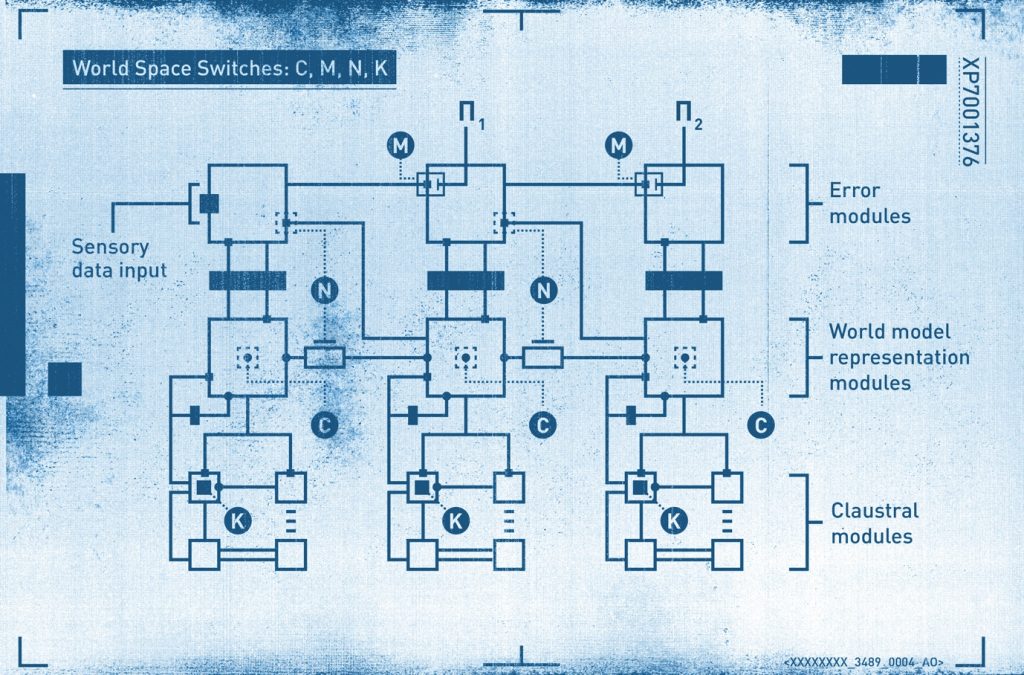

The number of possible patterns of column activation is a number so vast as to be practically incalculable, and, as such, the number of possible world models is of the same magnitude. Massive and yet finite, this set of patterns forms a state space representing all possible worlds a human could experience. And, since each state represents the entire experienced world at any moment, I refer to this state space as the World Space. It is within this World Space that we find the normal waking world and, indeed, where the alternate ‘reality channels’, including the DMT and Salvia worlds, must be found. So, we can see that your experience of a world is precisely its movement from state to state through this World Space. However, your brain doesn’t wander randomly through this space, but has sculpted its connectivity such that it naturally tends to adopt a limited repertoire of states, occupying only a tiny area of the World Space that comprise a functional and adaptive model of the environment. To discover and explore alternate worlds, the brain must reach out of this tiny World Space district into regions well beyond it. Psychedelic molecules are the tools to this end. To understand how they achieve this, we’ll begin by looking at a much simpler system.

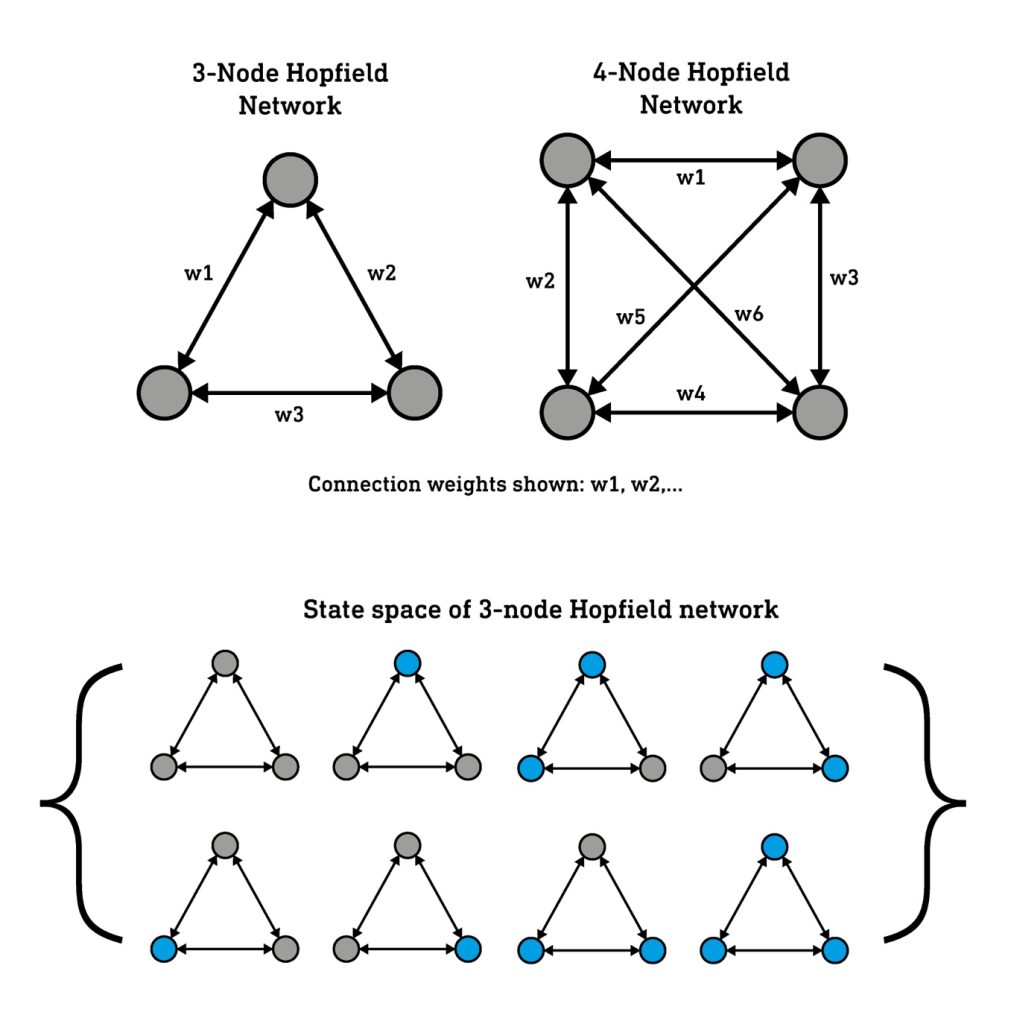

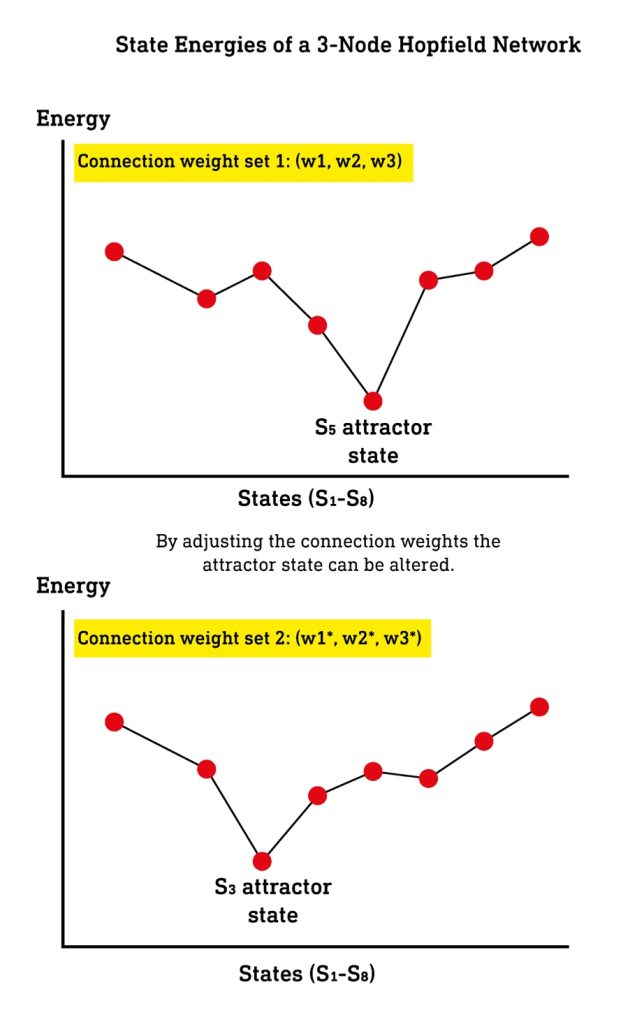

A Hopfield network is a simple type of artificial neural network — known as an attractor network — in which every node (corresponding to a neuron in a real brain) is connected to every other node9. Each node in the network can exist in either an active (blue) or inactive (grey) state, and all possible patterns of activation form the network’s state space (a much simpler equivalent of the cortex’s World Space).

No matter the starting state (activation pattern), a Hopfield network will always converge to one or more attractor states. However, the connection weights — equivalent to the strength of connections between neurons in the cortex — can be tuned such that any desired state becomes an attractor. In other words, the network can be used to store any particular pattern to which the network will move. Since the network moves away from certain states and towards the attractor states, these are described as high and low energy states, respectively. This is not unlike the way a marble will find its way to the base (the lowest energy attractor state) when dropped into a glass bowl. Low energy states are favoured states, whereas unfavoured states are high energy. Despite being far more complex than any Hopfield network, by virtue of its connectivity, the cortex also tends to move towards certain low energy attractor states and away from disfavoured high energy states. It’s the role of connectivity to ensure that the attractor states are those that represent a stable and functional model of the environment.

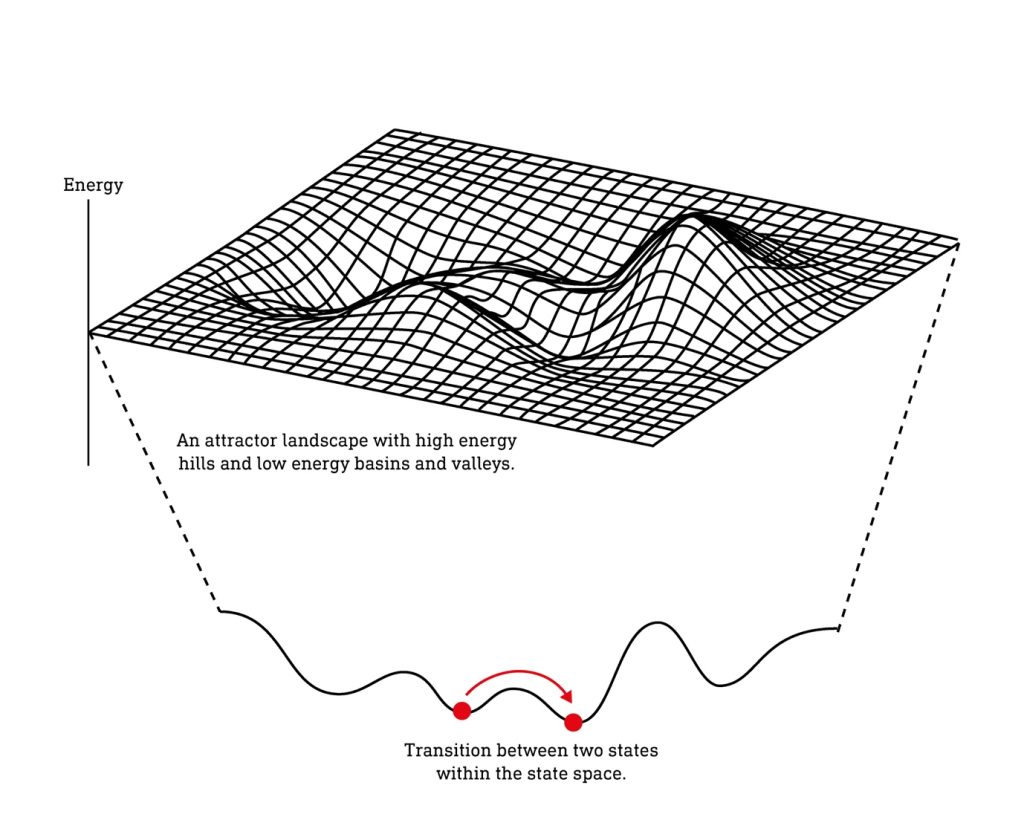

If we were to plot every possible state of the cortex — the entire World Space — on a plane, with the height above the plane representing the energy of the state, an energetic landscape or attractor landscape is generated, which I refer to as the World Space Landscape10. In an entirely unconnected cortex, in which every cortical column is activated independently, every state (pattern of column activation) would be equally likely, and the landscape would be perfectly flat — the cortex wouldn’t tend to move towards or away from any particular state, since there would be no relatively high and low-energy states. Of course, such a cortex would completely fail to represent any kind of meaningful model of the environment and would wander randomly from state to state. But, by sculpting its connectivity, a landscape with distinct high-energy hills and low-energy valleys and basins develops. Every low-energy state is essentially one that the cortex has “stored” by modifying its connectivity such that the state can easily be accessed. So, we can frame the entire process of tuning the connectivity between cortical columns as a sculpting of this World Space Landscape such that the low energy states form the most useful and adaptive model of the environment.

The role of sensory information, flowing in through the sensory apparatus, is to gently guide your cortex around the hills and valleys of this World Space Landscape. In the dream state, without this guidance from sensory information, the cortex wanders the Landscape more freely. But, naturally, it wanders along the low energy basins and valleys. As such, the world model in the dream state tends to be as with the normal waking world, since the overall shape of the World Space Landscape remains similar to its shape during waking11. The World Space Landscape isn’t fixed, however, but can be further moulded as the cortex adjusts its connectivity during development, learning, and experience. And, by amplifying or suppressing certain types of neurons and their connections, endogenous chemical neuromodulators (such as acetylcholine and serotonin) can also temporarily distort the shape of the landscape, as can psychedelic drugs12; 13.

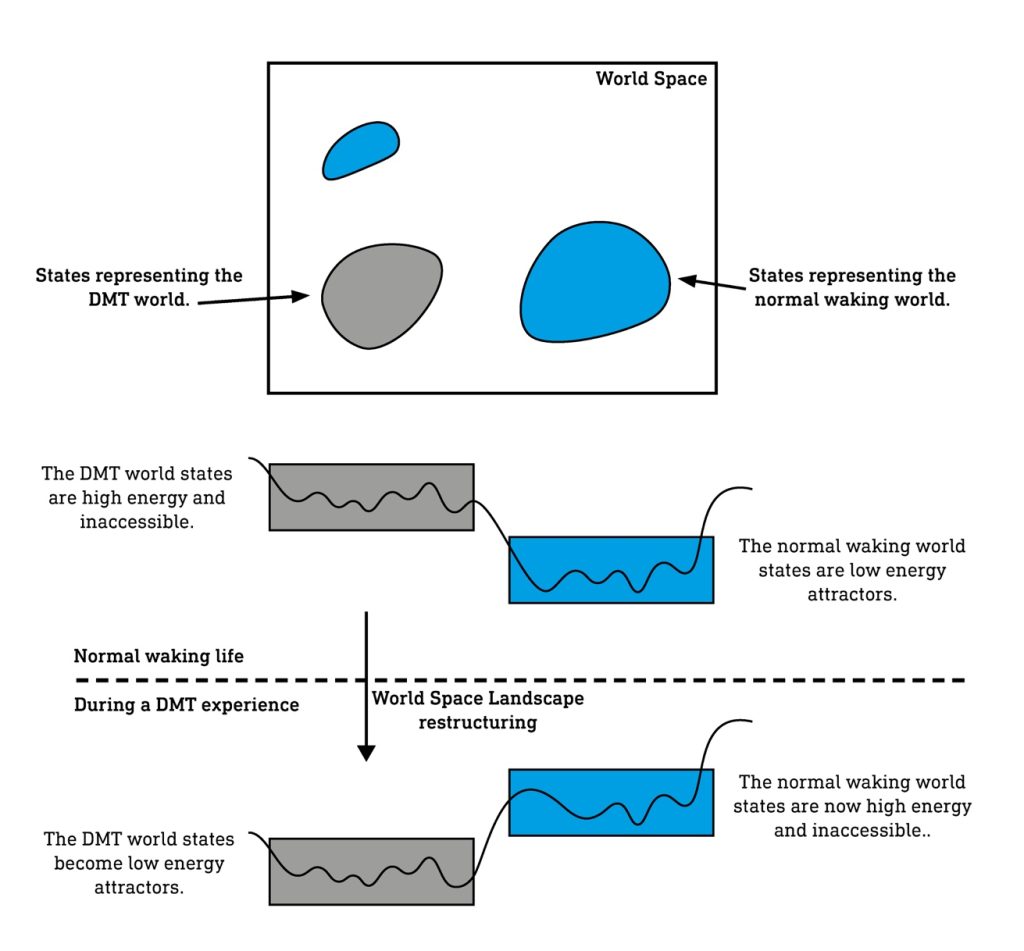

If we are to discover and explore novel worlds, the cortex must be able to reach those high-energy, disfavoured states that the cortex is, under normal circumstances, unable to access outside of the cluster of states that represent the normal waking world. The extremely bizarre DMT worlds, for example, are represented by states in entirely disjoint areas of the World Space Landscape. We can reach these normally disfavoured states by distorting the shape of the Landscape, lowering the energy of these states such that they become attractors, whilst raising the energy of the states representing the normal waking world. The cortex will then move naturally away from these states and towards the new attractor states and into a new region of the World Space. Psychedelic molecules provide the molecular perturbation that causes this temporary World Space Landscape restructuring, making available normally inaccessible states within the World Space.

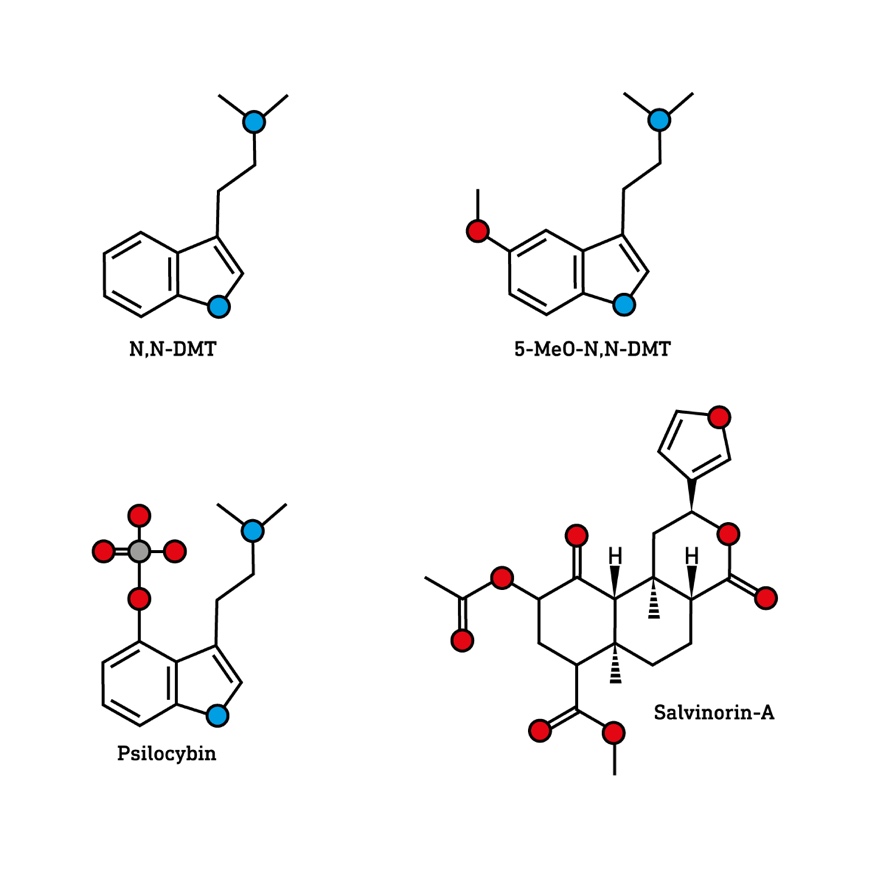

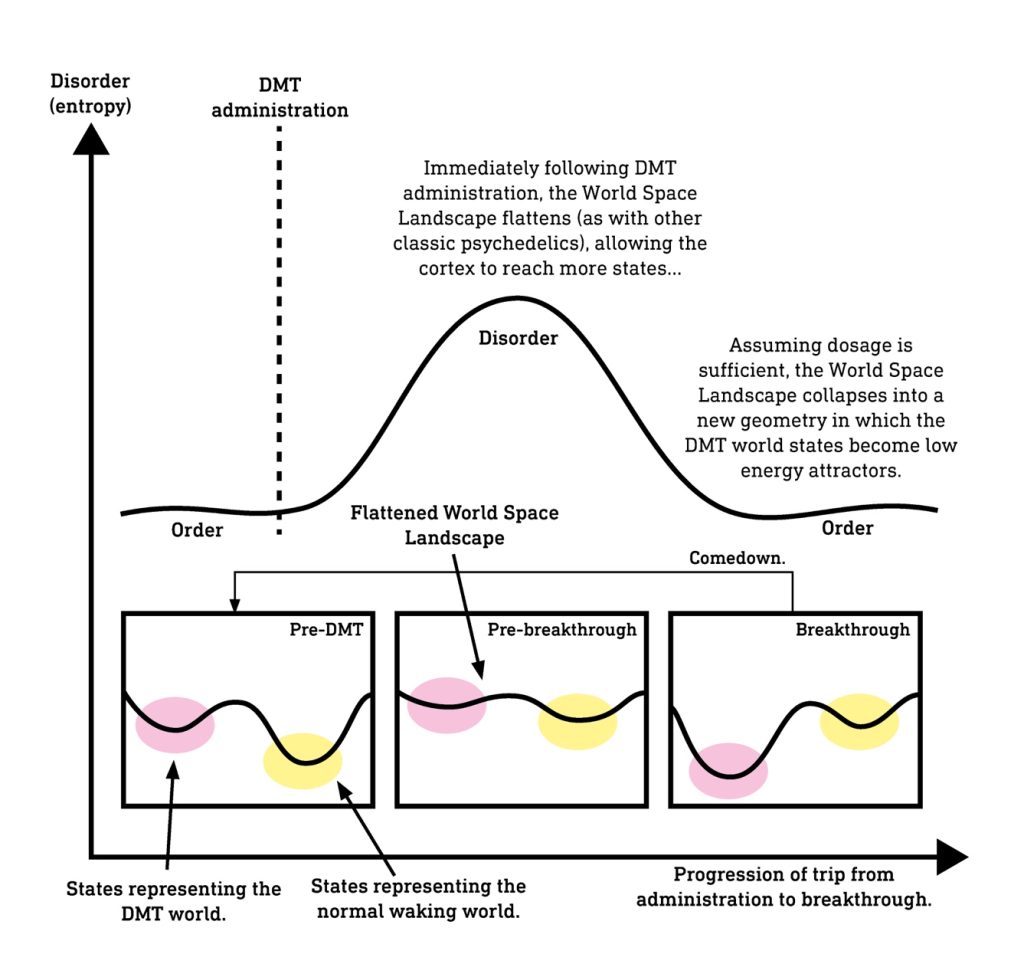

The classic psychedelics, such as LSD, psilocin, and DMT, act primarily at a type of serotonin receptor, the 5HT2A receptor, as well as having varying activity at other receptor (sub)types14; 15; 16. Activation of these receptors causes specific neurons in the deeper layers of the cortical columns to begin firing and sharing information between themselves more freely. This effectively overrides the finely tuned patterns of connectivity that control the maintenance of the world model and allows the cortex to reach entirely novel states, rather like heating a piece of glass until it becomes malleable and can be moulded into any desired form17; 18; 19; 20. The states that represent the normal waking world model are destabilised (their energy is raised), and the World Space Landscape flattens, allowing the brain to reach states previously disfavoured20. This attractor landscape flattening has recently been observed in human subjects given either LSD or psilocybin13. From your experiential perspective, your world becomes more fluid and dynamic, the identities of objects shift and transform before the eyes. The world begins to change.

DMT, however, pushes through this flattening phase and causes the World Space Landscape to collapse into a new, temporarily stable, structure in which the attractor states are completely separate from those of the normal waking world. This process begins almost immediately as the lungs are filled, as the world begins to break down and complex geometric forms at first veneer the world and then replace it entirely as the visions become increasingly wild and chaotic. Then, assuming the dosage is sufficient, a new world emerges from this chaos. There is a progression from order (the normal waking world) to disorder (the pre-breakthrough imagery) to a new order (the DMT worlds)21; 22. This procession corresponds to the World Space Landscape firstly being heavily disrupted and flattened and then collapsing into the new geometry — this is when the so-called “breakthrough” state is achieved, which is the experience of the cortex gliding through the valleys of this dramatically restructured World Space Landscape in an entirely separate area of the World Space.

As states representing the normal waking world are destabilised, the initial flattening of the World Space Landscape is quite simple to understand, but the subsequent collapse into a new structure needs further explanation. Fortunately, this kind of attractor landscape distortion isn’t unique to the cortex, but can also be observed in other complex systems. Take a society of ants, for example, which is a complex system that emerges from the interactions between large numbers of components: the individual ants. A large ant colony might comprise several million ants, with each ant type having its own well-defined roles in the organisation of the society. The queen is the leader and founder of the colony, her eggs fertilised by the male drone ants. Female worker ants are responsible for maintaining the nest, as well as protecting it from intruders and predators. Each individual ant is a rather simple creature and interacts with the other ants in rather simple ways. However, the entire colony can display highly sophisticated emergent behaviours: building elaborate networks of underground tunnels, delineating routes to food sources, defending against intruders, and even forming themselves into bridge-like structures over water23. Which behaviour emerges — which pattern of activity of the colony — depends upon the interactions between the ants. The Defend Against an Intruder behaviour is entirely distinct from the Build a Bridge behaviour, and the switch between them occurs because of highly specific changes in the interactions between the ants, mediated by pheromones and other signals24.

AntBridge by Igor Chuxlancev, (CCBY4.0)

Each dynamic behaviour comprises a set of states within a state space and, by altering their interactions, the ant society temporarily reshapes its attractor landscape such that the required behaviour emerges — whether building bridges or fighting intruders — at that time. Once the intruder has been defeated or the bridge completed, the interactions are again modified, the attractor landscape collapses into another shape, and another behaviour emerges. Like the normal waking world and the DMT world, the Defend Against an Intruder states and the Build a Bridge states occupy separate regions of the ant society state space and switching between them requires temporary restructuring of the attractor landscape such that the desired states become attractors.

Whether it’s an ant society, an artificial neural network, or the human cortex, certain highly specific perturbations or alterations in the interactions between the system components have the potential to distort the attractor landscape, change the states that act as attractors, and so shift the system towards radically different behaviours. In the case of the classic psychedelics, this perturbation is of the complex intracellular signalling network inside particular sets of neurons and of the interactions between them14; 25; 26. Salvinorin27 and the tropane alkaloids5 also provide such a perturbation, albeit utilising entirely distinct mechanisms and patterns of receptor stimulation, which I cover in great detail in Reality Switch Technologies.

Whether it’s DMT, 5-MeO-DMT, salvinorin, or the tropane alkaloids, the natural world has already provided us with a handful of molecules capable of perturbing the cortex and distorting the Landscape in their own unique way and each gating access to worlds previously unexplored. But I dare say we’ve only just begun to scratch the surface — the number of worlds we’ve yet to discover likely remains incomprehensibly vast. Unfortunately, since we’re dealing with a system far more complex than any ant society or artificial neural network, it’s extremely difficult (I dare say currently impossible) to design a molecule that will deliver the appropriate perturbation to restructure the World Space Landscape in a controlled way. We currently rely on a more brute force approach, tweaking the structure of known psychedelic molecules and observing their effects in human volunteers (or, in the case of Alexander Shulgin, on himself).

However, in the future, once we’ve developed a more complete understanding of how psychedelic molecules interface with the world building machinery of the human brain, it might be possible to actually control this reconfiguration of the World Space Landscape such that any desired World Space location becomes accessible to the cortex. Indeed, it might even be possible to map the World Space with a coordinate system developed for the purpose. Accessing a particular region of the World Space might ultimately be as simple as dialling the coordinates into specially designed software, which would calculate the appropriate receptor stimulation pattern necessary to generate the vector into that World Space location before lying down for the programmed infusion of the appropriate molecules. The extended-state DMT infusion technology28, which has come to be known as DMTx, will likely be invaluable in the development of the techniques and tools required to navigate and possibly map these new worlds as we discover them.

Whatever you might believe about the so-called “ontological status” of these worlds and their curious inhabitants; whether you believe them to be mapped to some kind of external environment within which conscious intelligent beings reside, or whether you believe them to be wild fabrications of the human brain, the fact that we each carry around in our heads a machine capable of constructing a practically infinite array of worlds of such inexpressible complexity and beauty is, in itself, almost miraculous. The World Space of the human brain is a truly wondrous thing and ought, in my opinion, to be explored with as much vigour and ambition as with which we reach with our rocket ships to the stars. Children at play across the endless landscapes of the mind. Worlds without end.

References

1 GALLIMORE, A. R.; LUKE, D. P. DMT research from 1956 to the edge of time. In: KING, D.;LUKE, D., et al (Ed.). Neurotransmissions – An Anthology of Essays on Psychedelics from Breaking Convention. 1st: Strange Attractor Press, 2015.

2 LLINAS, R. R.; PARE, D. OF DREAMING AND WAKEFULNESS. Neuroscience, v. 44, n. 3, p. 521-535, 1991. ISSN 0306-4522. Disponível em: < <Go to ISI>://WOS:A1991GH27100001 >.

3 SIEBERT, D. J. Salvia divinorum and salvinorin A: new pharmacologic findings. J Ethnopharmacol, v. 43, n. 1, p. 53-6, Jun 1994. ISSN 0378-8741. Disponível em: < https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7526076 >.

4 METZINGER, T. The Ego Tunnel. Basic Books, 2009.

5 MÜLLER, J. L. Love potions and the ointment of witches: historical aspects of the nightshade alkaloids. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol, v. 36, n. 6, p. 617-27, 1998. ISSN 0731-3810. Disponível em: < https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9776969 >.

6 TSUNODA, K. et al. Complex objects are represented in macaque inferotemporal cortex by the combination of feature columns. Nature Neuroscience, v. 4, n. 8, p. 832-838, Aug 2001. ISSN 1097-6256. Disponível em: < <Go to ISI>://WOS:000170137300017 >.

7 SPORNS, O.; TONONI, G.; EDELMAN, G. M. Connectivity and complexity: the relationship between neuroanatomy and brain dynamics. Neural Networks, v. 13, n. 8-9, p. 909-922, Oct-Nov 2000. ISSN 0893-6080. Disponível em: < <Go to ISI>://WOS:000166070200008 >.

8 BLAKEMORE, C.; COOPER, G. F. Development of the brain depends on the visual environment. Nature, v. 228, n. 5270, p. 477-8, Oct 31 1970. ISSN 0028-0836. Disponível em: < https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5482506 >.

9 HOPFIELD, J. J. Neural networks and physical systems with emergent collective computational abilities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, v. 79, n. 8, p. 2554-8, Apr 1982. ISSN 0027-8424. Disponível em: < https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6953413 >.

10 GU, S. et al. The Energy Landscape of Neurophysiological Activity Implicit in Brain Network Structure. Sci Rep, v. 8, n. 1, p. 2507, Feb 06 2018. ISSN 2045-2322. Disponível em: < https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29410486 >.

11 SCHREDL, M.; HOFMANN, F. Continuity between waking activities and dream activities. Consciousness and Cognition, v. 12, n. 2, p. 298-308, Jun 2003. ISSN 1053-8100. Disponível em: < <Go to ISI>://WOS:000183227200009 >.

12 KANAMARU, T.; FUJII, H.; AIHARA, K. Deformation of attractor landscape via cholinergic presynaptic modulations: a computational study using a phase neuron model. PLoS One, v. 8, n. 1, p. e53854, 2013. ISSN 1932-6203. Disponível em: < https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23326520 >.

13 SINGLETON, S. P. et al. Receptor-informed network control theory links LSD and psilocybin to a flattening of the brain’s control energy landscape. Nat Commun, v. 13, n. 1, p. 5812, Oct 03 2022. ISSN 2041-1723. Disponível em: < https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36192411 >.

14 NICHOLS, D. E. Psychedelics. Pharmacological reviews, v. 68, n. 2, p. 264-355, 2016 2016. ISSN 1521-0081. Disponível em: < <Go to ISI>://MEDLINE:26841800 >.

15 GLENNON, R. A.; TITELER, M.; MCKENNEY, J. D. EVIDENCE FOR 5-HT2 INVOLVEMENT IN THE MECHANISM OF ACTION OF HALLUCINOGENIC AGENTS. Life Sciences, v. 35, n. 25, p. 2505-2511, 1984. ISSN 0024-3205. Disponível em: < <Go to ISI>://WOS:A1984TT08300004 >.

16 VOLLENWEIDER, F. X. et al. Psilocybin induces schizophrenia-like psychosis in humans via a serotonin-2 agonist action. Neuroreport, v. 9, n. 17, p. 3897-3902, Dec 1998. ISSN 0959-4965. Disponível em: < <Go to ISI>://WOS:000077790300024 >.

17 CARHART-HARRIS, R. L. et al. Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, v. 109, n. 6, p. 2138-2143, Feb 2012. ISSN 0027-8424. Disponível em: < <Go to ISI>://WOS:000299925000068 >.

18 MUTHUKUMARASWAMY, S. D. et al. Broadband Cortical Desynchronization Underlies the Human Psychedelic State. Journal of Neuroscience, v. 33, n. 38, p. 15171-15183, Sep 2013. ISSN 0270-6474. Disponível em: < <Go to ISI>://WOS:000324586500023 >.

19 CARHART-HARRIS, R. L. et al. The entropic brain: a theory of conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with psychedelic drugs. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, v. 8, p. 22, Feb 2014. ISSN 1662-5161.

20 TAGLIAZUCCHI, E. et al. Enhanced Repertoire of Brain Dynamical States During the Psychedelic Experience. Human Brain Mapping, v. 35, n. 11, p. 5442-5456, Nov 2014. ISSN 1065-9471. Disponível em: < <Go to ISI>://WOS:000344176100009 >.

21 ALAMIA, A. et al. DMT alters cortical travelling waves. Elife, v. 9, Oct 12 2020. ISSN 2050-084X. Disponível em: < https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33043883 >.

22 TIMMERMANN, C. et al. Neural correlates of the DMT experience assessed with multivariate EEG. Sci Rep, v. 9, n. 1, p. 16324, Nov 19 2019. ISSN 2045-2322. Disponível em: < https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31745107 >.

23 LIONI, A.; DENEUBOURG, J. L. Collective decision through self-assembling. Naturwissenschaften, v. 91, n. 5, p. 237-41, May 2004. ISSN 0028-1042. Disponível em: < https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15146272 >.

24 ICHIMURA, T. et al. Emergence of altruism behavior in army ant-based social evolutionary system. Springerplus, v. 3, p. 712, 2014. ISSN 2193-1801. Disponível em: < https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25674453 >.

25 ROTH, B. L. et al. Identification of conserved aromatic residues essential for agonist binding and second messenger production at 5-hydroxytryptamine2A receptors. Mol Pharmacol, v. 52, n. 2, p. 259-66, Aug 1997. ISSN 0026-895X. Disponível em: < https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9271348 >.

26 NICHOLS, D. E. Chemistry and Structure-Activity Relationships of Psychedelics. Curr Top Behav Neurosci, v. 36, p. 1-43, 2018. ISSN 1866-3370. Disponível em: < https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28401524 >.

27 ADDY, P. H. Acute and post-acute behavioral and psychological effects of salvinorin A in humans. Psychopharmacology, v. 220, n. 1, p. 195-204, Mar 2012. ISSN 0033-3158. Disponível em: < <Go to ISI>://WOS:000300780400018 >.

28 GALLIMORE, A. R.; STRASSMAN, R. J. A Model for the Application of Target-Controlled Intravenous Infusion for a Prolonged Immersive DMT Psychedelic Experience. Frontiers in Pharmacology, v. 7, p. 11, Jul 2016. ISSN 1663-9812. Disponível em: < <Go to ISI>://WOS:000379571400002 >.

Hi andrew, Love the fact that someone as educated as you are is conducting this research. I live in cape town and i was wondering if you know anyone there that I could discuss this topic with? Best wishes, Steve

Hi Steve. Thanks for reading! I don’t know anyone in Cape Town (or SA at all actually!), so can’t help you there — seems like a gap in the market for some kind of psychedelic circle though.

Sign me up for DMTx! How do I volunteer?

Also, a comment: coming from Continental philosophy and phenomenology, I am working on John Lilly’s use of George Spencer-Brown’s calculus from his 1969 Laws of Form. I was a friend of Spencer-Brown and have recently been involved in hosting conferences on his work, establishing a formal society, and securing forthcoming publications in this area. My own work takes his central device, which Lilly employed as an operator in his float tank psychedelic programming, as the vehicle of transit in a manifold based on the ancient Hermetic hypostasis of the infinite sphere. This sphere-center framework has enough room for the forms of many levels in Spencer-Brown’s calculus of indications, which are also levels of being in ontological phenomenology and universal ontology. The ontology of early phenomenologist Hedwig Conrad-Martius, who also a a framework of enough room for absolutely everything, is the main thing I’m exploring at this time to build my PhD dissertation (in philosophy at The New School for Social Research). Conrad-Martius was a powerful mystic, and the godmother of St. Benedicta of the Cross Edith Stein, whose entelechial-hyletic scientific metaphysics starts from the contemporary scientific paradoxes of quantum and relativistic paradigms, as well as the Kantian antinomies and Aristotelian problems of space and time. This is akin to Spencer-Brown’s building upon the famous paradox of his teacher Bertrand Russell. In both cases, a mystical resolution is discovered in the agitation of dianoetic approaches to the expression of these paradoxes. This convergent mystical perspective is not only a personal paradigm but is the great work of our world age in a theosophical sense. The paradigm of the sphere, like Timaeus’ sphere of the paradigm, is the great universal science applicable as the limit case of all special disciplines, and also an ultra-simple intuitive device you can take with you to all possible domains, like the fabled sphere of Atlas in the prisca philosophia.

I appreciate your situating of this topic of cognitive science or perception, world view, and ‘personality’, in philosophy. But why do you, and the author, not mention archetype at all? Plato (his serious half) did develop that philosophy. Psychology (Freud, Jung) did develop archetype further. Kant and Heidegger too, though under different labels (manifestation or physis, dighe or self-organisation). Perhaps the ideal framework for this subject is meaning itself, semiotics. Which clearly involves archetype (universal diction, behaviour, constants, etc).

Entities in ‘hyperspace’ are clearly recurrent, and archetypal (to the point of finding universal parallels in myth, novels, movies, dreams, etc). Despite slightly different styling in slightly different cultures and ages (noting that styling is inherently meaningless, and useful only for tribal bonding and exploitation; or class level bonding and mutual exploitation).

Andrew, your article seems to hang suspended without a theoretical framework. Attractor states is also a term used in anthropology (also labelled Biases). Which are subject to laws, thus to structuralist approaches (as distinct from diffusionist, ‘evolutionary’, etc approaches). Your main work seems to quantify mechanisms of perception, not the core content of such. Quantification of behaviour is a structuralist approach.

I work mainly on the content of perception and re-expression in cultural media. Here is my only article about a mechanism of perception, involving the cingulated cortex and spatial cognition, on which I invite both of you to comment: https://stoneprintjournal.wordpress.com/2018/03/04/taxi-drivers-exercise-the-knowledge/

I had moved my comment to the AOM Message Board, where Andrew responded.