It’s our pleasure to welcome Andrew Collins, author of Karahan Tepe: Civilisation of the Anunnaki and the Cosmic Origins of the Serpent of Eden, as our featured author this month. Andrew’s book is a detailed investigation of one of the world’s most important archaeological discoveries—Karahan Tepe, an enormous complex of stone structures in southeastern Turkey covering an estimated ten acres. Andrew presents the first in-depth investigation of the discoveries at the site: who built it, its astronomical alignments, and its cosmological connections.

In his article below, Andrew takes the reader on a captivating exploration of Karahan Tepe, delving deep into the meanings behind the intricate symbolism of this vast stone structure and the age-old cosmic mythology surrounding it.

Interact with Andrew on our AoM forum here.

Karahan Tepe in southeastern Turkey is a Pre-Pottery Neolithic site situated beyond the eastern edge of the fertile Harran plain in the remote Tektek Mountains. It forms part of a post-ice age technocomplex known today as Taş Tepeler, meaning “stone hills.” The name refers to the culture’s use of carved stone T-pillars and occupational mounds called in Turkish tepes or höyüks. To date, around 12 such tepes have been investigated, almost all of which are located in the country’s Şanlıurfa region (see Fig. 1 for a map of the region). We look at its archaeological features and determine their archaeoastronomical importance with special regard to the solstices, the Milky Way, the Galactic Bulge, and constellations such as Scorpius, Sagittarius, Ophiuchus and Cygnus. What this appears to reveal is a deep interest in cosmological values that can be found also at Göbekli Tepe by way of the carved imagery on its infamous Pillar 43. The origins of these cosmogonic and cosmological notions, along with the technology and innovation behind the Taş Tepeler project, can, it seems, be deemed to have emerged as far back as 30,000-45,000 years ago at Initial Upper Paleolithic sites such as the Denisova Cave in Siberia and Tolbor 16 in Mongolia.

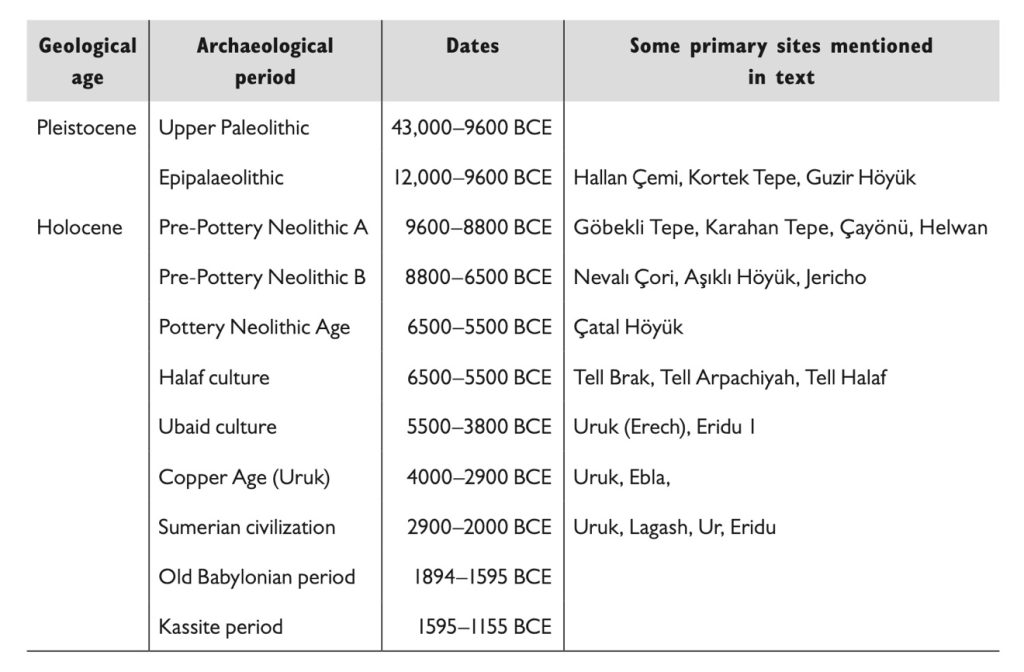

Karahan Tepe is contemporaneous with its sister site of Göbekli Tepe, situated some 23 miles (37 kilometers) to the west-northwest. The discovery at Karahan Tepe of plant remains, including a form of wild wheat, shows that widescale occupation of the Tektek Mountains began during the late Epipaleolithic Age (circa 11,000 BCE). Extensive building activities, however, did not begin at Karahan Tepe until the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A period (circa 9400 BCE), after which they continued through to the Early Pre-Pottery Neolithic Neolithic B (around 8500-8000 BCE). Thereafter, the site was abandoned until Roman times (see Fig. 2 for a timeline of dates).

Karahan Tepe’s discovery in the mid 1990s, along with early survey work carried out at the location by Dr Bahattin Çelik of Harran University, has been described elsewhere.[1] Since 2019 excavations have taken place there under the directorship of Dr. Necmi Karul of Istanbul University.[2] Three interconnected sub-surface structures were revealed during excavations between 2019 and 2021. These lay beneath a thick layer of soil and rubble covering the hill’s eastern and northeastern slopes. Dating to circa 9400-9000 BCE, they are referred to by archaeologists as Structures AA, AB, and AD.

Figure 1. Map of the Şanlıurfa region showing the principal Taş Tepeler sites. Credit: Andrew Collins

Figure 2. Timeline of the Neolithic age in Anatolia and the Near East giving examples of sites from each phase. Credit: Andrew Collins

Structure AD (the Great Ellipse)

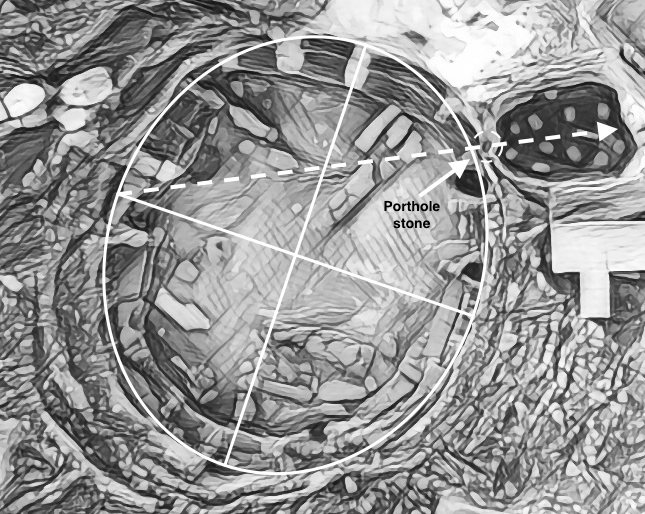

The largest of the three installations, Structure AD (known also as the “Great Ellipse”), is elliptical in shape with a maximum length of 23 meters (75 feet) and a width of approximately 20 meters (65 feet). The northern, eastern and southern sections of its perimeter wall are made up of dry-stone walling with a thickness of around 1.5 meters (5 feet). It is orientated 10 degrees south of east and has an underlying geometrical pattern reflecting a whole number ratio of 32:27, which features as an important interval in much later Pythagorean musical scales.

Built into the enclosure’s retaining wall, as well as into the bedrock at its western termination, were originally 18 T-pillars. Between them were stone benches similar to those found at other Pre-Pottery Neolithic cult centers (see Fig. 3 for an overhead plan of Structure AD, and Figs. 4 & 5 showing what it looks like today). At least one of the bench tops remaining in situ is clearly the stem of an old T-pillar since it displays carved decoration on its front narrow edge (see below for more details).

Figure 3. Overhead view of Karahan Tepe’s Structure AD (the Great Ellipse) showing its underlying geometry, axial alignment, and relationship to Structure AB (the Pillars Shrine). Credit: Andrew Collins

A number of limestone statues, as well as several large platters carved from a variety of stone materials, were found during excavations on or around the benches. These would appear to have been deliberately left in situ when the structure was decommissioned and afterwards buried beneath soil and rubble, an act perhaps seen as “killing” or “putting to rest” the enclosure’s active spirit.

Central Pillars

At the center of Structure AD, two enormous T-pillars would have stood within holes cut into the bedrock. Today these pillars are in multiple fragments, although their original positions can still be determined. Whether or not they were deliberately broken or were the subject of natural fracture and erosion before their eventual burial is unclear.

Piecing together the various fragments of these twin pillars tells us they were just slightly smaller than an unfinished example seen still attached to the bedrock on the hill’s western-facing slope. This is approximately 5.5 meters (18 feet) in length. The carved decoration on the western central pillar shows two vertical lines in high relief that curve outward just beneath the T-shaped head. It is difficult to know exactly what this represents, although it probably signifies the parallel hems of a draped garment.

Buttresses and Thrones

The western half of Structure AD is entirely unique. Three enormous carved stone benches have been cut directly out of the hill’s bedrock (see Fig. 6). Each one bears the likeness of a rock throne, and on them, one can imagine community elders sitting during important rituals and ceremonies.

Figure 6. The rock-cut buttresses and thrones at the western termination of Karahan Tepe’s Structure AD. Credit: Andrew Collins

Dividing the stone thrones, which have an additional kerb or step at their base, are three (originally four) towering buttresses, each one cut entirely out of the hill’s eastern slope to a maximum height of 4.3 meters (14 feet). These acted as solid rock variations of the anthropomorphic T-pillars that occupied the rest of the enclosure, although their terminations have long since vanished due to exposure to the elements. Together they constituted four of the 18 standing pillars that faced into the center of the installation; 18 being a highly symbolic number that might well reflect an interest in the movements of the sun and moon, perhaps the 18-year Saros eclipse cycle, or the 18.61-year lunar standstill cycle.

Two of the rock-cut buttresses, the most southerly of the four, display carved relief showing what appear to be leopard-skin pelts below their presumed waistlines; these appear on their front narrow edges. Archaeologists working at the site suggest the carvings are leopards, although they are more likely loincloths similar to the fox pelt examples seen on the two central pillars in Göbekli Tepe’s Enclosure D (Pillars 18 and 31).

Such a realization suggests that Karahan Tepe’s occupants wore leopard skin pelts as loincloths, arguably during rituals and ceremonies. A similar leopard pelt loincloth can be seen on the front narrow edge of the T-pillar being used as a bench seat on the northern side of the enclosure—see Fig. 7.

Figure 7. T-pillar on its side being used as a bench in Structure AD showing the leopard skin loincloth on its front narrow edge (arrowed). Credit: Andrew Collins

Structure AB—The Pillars Shrine

Rock architecture is present at Karahan Tepe in an even more spectacular manner within Structure AB, also known as the Pillars Shrine (see fig. 8). This is located immediately to the north-northwest of Structure AD to which it is linked via a 27.5 inch (70 centimeter) rectangular porthole window cut into a thin wall of rock deliberately left in situ for this purpose. On the other side of this window are five crudely carved steps leading down to the structure’s stone floor.

Carved entirely out of the hillside, the Pillars Shrine is trapezoidal in shape with rounded corners. In size it is 7 meters (23 feet) in length with a maximum width of 6 meters (20 feet), its southern end narrower than its northern end. The room’s limestone walls rise to a height of 2.3 meters (7.6 feet), beyond which is the artificially leveled rock surface.

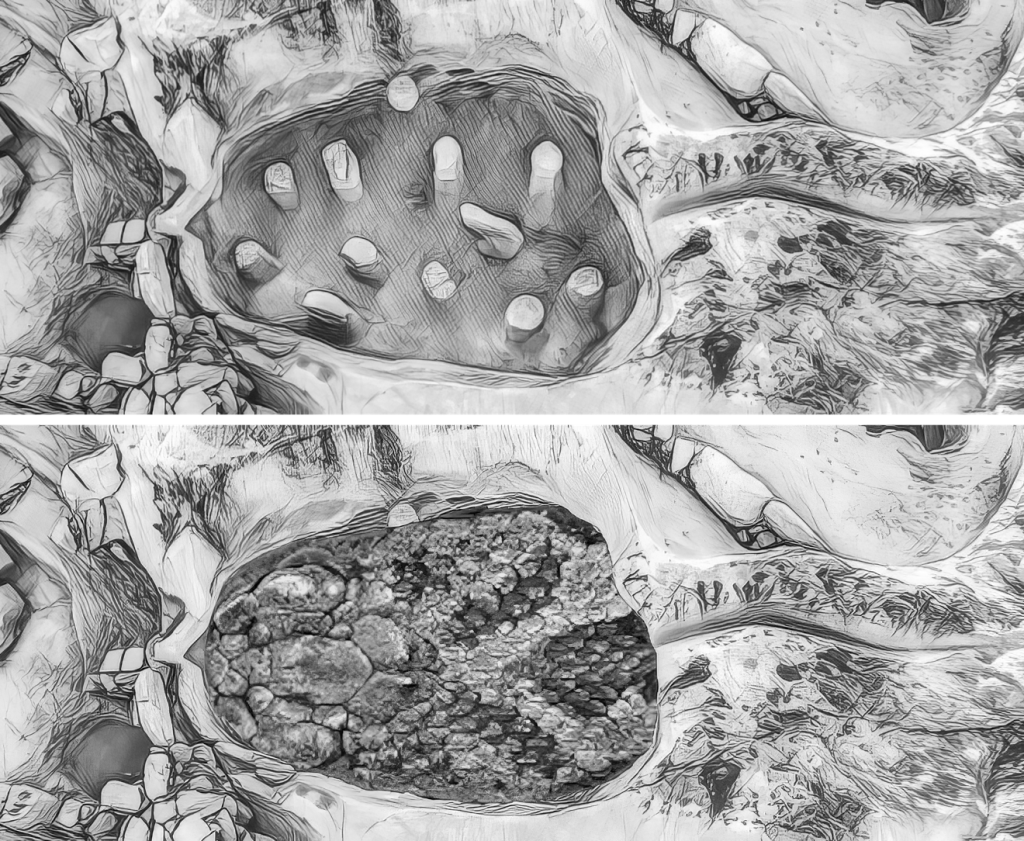

Filling the interior of Structure AB are 11 standing pillars, 10 of which are fashioned directly out of the bedrock. Four, located close to the shrine’s western wall, stand in a north-south line. Each one is approximately 1.6 to 1.7 meters (5.25 feet to 5.6 feet) in height, with slightly wider heads as terminations, making them phallic in appearance.

Figure 8. View of Karahan Tepe’s Structure AB (the Pillar’s Shrine) looking southwestwards. Credit: Andrew Collins

The other six rock-hewn pillars are smaller in size. They vary between 1 to 1.4 meters (3.25 to 4.6 feet) in height and are between 30–50 centimeters (12 to 20 inches) in thickness. Five are positioned roughly north-south in a noticeable zigzag pattern, while the sixth example is located slightly back from the others, close to the structure’s southeastern corner. Some of the smaller pillars also have slightly larger heads, while the most northerly example has what appears to be a tethering hole two-thirds the way up its southern side. This could have been used to attach a rope or cord, although for what purpose is unclear.

Some intimate relationship must have existed between all ten pillars, a point to remember as we explore the shrine’s eleventh pillar, which rises to the same approximate height as the tallest of the rock-cut columns. Unlike Structure AB’s other pillars, this one was not cut out of the bedrock. Instead, it was carved into shape before being placed upright in a rectangular slot cut into the shrine’s stone floor (see Fig. 9). Significantly, it is crescent-shaped with a slightly wider head, offering the impression of a striking snake facing towards anyone entering the shrine. This suspicion is further emphasized by a linear indentation on the stone’s western side corresponding to the position of the creature’s “mouth” (some have suggested you can even see an eye immediately above the mouth).

The Giant Stone Head

The importance of snake symbolism in the Pillars Shrine is further indicated by the presence on the shrine’s western wall of something quite extraordinary. Carved once again out of the bedrock, about 2.1 meters (7 feet) off the ground and in the central area of the rock face, is a giant human head at the end of a long vertical neck. The head is enormous, being as much as three times that of a normal human being (see Fig. 10). On the underside of the neck are a series of parallel striations perpendicular to its angle of projection. These are there to emphasize its serpentine nature.

The head itself is turned slightly towards the structure’s entrance porthole (its approximate orientation is just south of east). Its mouth, carved in high relief, is elliptical in shape, offering the impression that the head is talking to you.

The flat area on the top of the head gives the whole thing the appearance of a medieval knight wearing a helmet complete with nose guard. This is, however, an illusion since its flat top probably marks the level of a roof or covering that almost certainly enclosed the shrine. This seems confirmed by the knowledge that horizontal ledges at the same height as the top of the head can be seen above the shrine’s walls on its eastern and western sides. These presumably supported cross beams of some kind.

Structure AA—The Pit Shrine

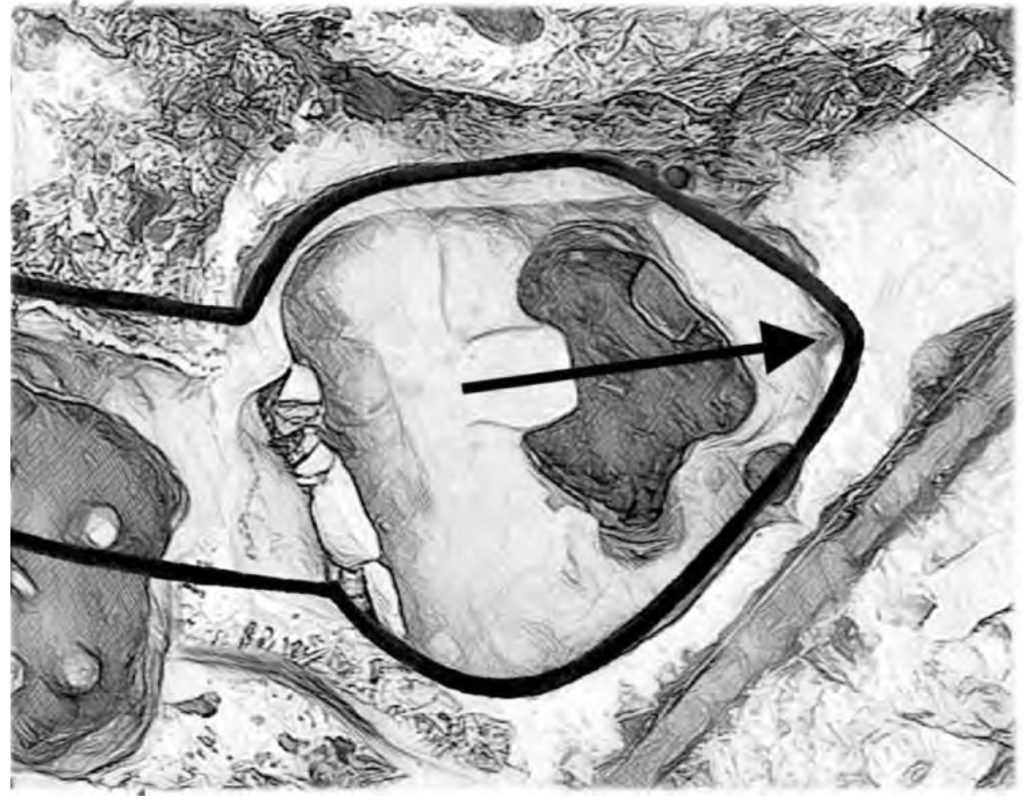

On the north side of the Pillars Shrine, cut into the level bedrock, is a deep winding groove that connects with the southeastern edge of a third and final sub-surface feature. Referred to as Structure AA or the Pit Shrine (see Fig. 11), it is trapezoidal in shape with rounded corners. It is approximately 8.5 meters (28 feet) in length, 7 meters (23 feet) across, and around 1.1 meters (3.5 feet) in depth, making it much shallower than the previously described installations.

Within the structure’s western wall is a curved bench around 3.6 meters (12 feet) in length. On its front vertical face is an extremely long snake incised using what is known as the scraping technique (see Fig. 12). Its head, which displays two faint eyes, is turned upwards. The snake itself faces north, and immediately beyond its head is a standing fox in low relief that also faces north.

Figure 12. Incised snake on the long bench seen in Karahan Tepe’s Structure AA (with the creature’s head arrowed). Credit: Andrew Collins

Cut into the level floor at the room’s northern end is an irregular shaped pit with rounded corners that descends into the bedrock for a depth of around 2.3 meters (7.5 feet). At ground level on the pit’s western side is a carved recess large enough for a person to crawl inside.

The Experiencer’s Journey

Steps carved into the shrine’s eastern wall allow access into the room. Interestingly, their position corresponds very roughly to the end of the aforementioned winding groove. In fact, close to the other end of this groove, four similarly carved steps lead down into the northeastern corner of the Pillars Shrine. This suggests a connection between the two structures, almost as if when you have finished in one, the curved line guides you to the other (see Fig. 13).

Necmi Karul writes that those entering the Pillars Shrine likely crawled through the porthole stone from Structure AD (the Great Ellipse).[3] They would then have exited the room via the steps in its northeastern corner. If correct, it means the supplicant would have followed the deep winding groove afterwards before stepping down into the Pit Shrine for whatever was to take place there.

Figure 13. The long, deeply carved groove cut into the bedrock that runs between Karahan Tepe’s Structure AB and Structure AA. Credit: Andrew Collins

Questions remain, however, like who would have sat on the Pit Shrine’s long bench, part of which overlies the deep hole carved into the floor? Could this pit have been used to contain live animals, snakes perhaps, or did supplicants lie down within its carved recess as part of some ritual process? If the latter, then it should be pointed out that there appears to be no obvious means of descending into the hole, meaning that access must have been via a rope or a ladder.

Suggestions that the pit might have been filled with water overcome the problem of how entry was made, although it raises further questions regarding its function. Could the pit have been a kind of plunge pool into which the experiencers submerged themselves to obtain an altered state of consciousness? If so, what was the purpose of this act, and what might it have achieved?

The fact that the deeply cut groove linking the Pillars Shrine with the Pit Shrine resembles a moving snake is unlikely to be without meaning. Karul himself has described it as a “serpentine channel.”[4] The possibility that the curved groove could have been used to carry water or some other liquid only adds to the mystery.

Inside the Snake’s Head

The serpentine nature of all these shrines is significant, especially in the knowledge that from an overhead position, the Pillars Shrine resembles a snake’s head with its neck and body highlighted by the deep groove on its northern side. Is this what the structure was meant to represent—a three-dimensional snake head?

One snake species indigenous to the Tektek Mountains is the highly venomous Anatolian meadow viper (Vipera anatolica). Synchronizing its head with the overhead profile of the Pillars Shrine provides a near-perfect match (see Fig. 14).

Figure 14. Overhead view of Structure AB, above, and below, the shrine with the head of the Anatolian meadow viper (Vipera anatolica) overlaid. Credit: Andrew Collins

During the 2023 campaign, a small enclosure located to the east of the Great Ellipse (Structure AD) was investigated. Dubbed the Kitchen, excavations showed it to contain a large quantity of animal bones, many belonging to the Anatolian meadow viper. This confirms not only that the species was known to the inhabitants, but also that this particular species almost certainly featured in rites taking place there. The idea then that the Pillars Shrine represents the head of the Anatolian meadow viper makes complete sense especially if the creature was seen to be imbued with magical power.

If these speculations are correct, then anyone entering the Pillars Shrine via its porthole window would have done so through the snake’s jaws, meaning that once inside, they would have been within the creature’s mouth. Did its ten bedrock pillars signify the snake’s teeth, with its curved eleventh pillar representing its tongue?

Incredibly, Structure AB might not be the only enclosure at Karahan Tepe shaped to resemble a snake’s head. An overview of the Pit Shrine (Structure AA) can be seen to resemble the stylised head of the long snake incised on the front edge of its long bench (see Fig. 15).

Figure 15. The head of the incised snake on the bench within Structure AA overlaid on an overhead view of the shrine. Credit: Andrew Collins

It therefore looks possible that the entire journey of the supplicant started in the Great Ellipse (Structure AD), continued into the Pillars Shrine (Structure AB), in its capacity as a snake head, and culminated in the Pit Shrine (Structure AA). Thereafter, the person would have climbed out onto the level bedrock either via the steps at the end of the Pit Shrine’s long bench or via the steps cut into its northeastern wall. The same basic journey is proposed by Karul, who writes:

Str. AB [the Pillars Shrine] is reached by passing through Str. AD [the Great Ellipse]; there is also a connection from Str. AB to Str. AA [the Pit Shrine]. Nonetheless, the main entry is via Str. AD. Therefore, we could assume Str. AD to be the actual place of activities that took place in this structure. The present evidence strongly suggests a ceremonial process, entering the building from one end and exiting at the other end, having to parade in [the] presence of the human head featuring a phallic symbolism.[5]

This ritualistic directionality also makes sense of another observation made by Karul. The three interconnected structures uncovered at Karahan Tepe are all on the hill’s eastern or northeastern slopes. No cult structures have been found on the hill’s western or southern faces. This has led Karul to surmise that the site’s southern plain “must be the living area of the dwellers of the settlement.”[6]

The Structures as Living Entities

The manner the community at Karahan Tepe viewed the three rock-cut structures can perhaps be seen in the fact that after their useful life each one was deliberately buried beneath layers of soil and rubble, a process that Karul suggests is evidence of a systematic decommissioning process. In his words:

The burial of buildings is somewhat comparable to that of human burials, signifying the strength of the meaning attached to the building … Considering the labor and time required for the construction of such structures, they must have held great meaning for Neolithic societies.[7] (Original author’s emphasis.)

The structures would thus seem to have been treated as living entities inhabited in the same manner that in many cultures a person’s physical body is seen to be animated by a non-physical force or spirit. As such these enclosures had to be treated with due respect even after they had completed their useful life. They were ritually “killed” and afterwards “buried” in a manner befitting a human being.

Additional Enclosures

Beyond these three enigmatic structures are other enclosures that should be mentioned. They include Structure AC, a more basic feature, crescent in shape, that has been cut out of the sloping bedrock to the east of the Pit Shrine. It was found buried beneath tons of rubble, perhaps as part of a decommissioning process similar to that undertaken in connection with the shrines already described. At its southern end is a long, curved, rock-cut bench that was clearly meant for those inside to gaze out towards the northern and northeastern horizons should they have been visible from its interior.

On the southern side of the three interconnected structures are several further enclosures built into the hill’s lower slope. These appear similar in design to Layer II features at Göbekli Tepe, indicating that they date from the early stages of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (circa 8800-8000 BCE). Each contains pairs of T-pillars in sizes ranging in height from 1.4 meters to approximately 3 meters (4.5 feet to 10 feet). Some of the pillars display anthropomorphic features such as articulated arms and hands, which terminate in long, spindly fingers that curl around onto their front narrow edges. Above these hands are often parallel vertical lines, signifying garment hems, along with v-shaped “neckties.” All these features are seen in connection with T-pillars found at almost all Taş Tepeler sites.

Curiously, the number of fingers shown on T-pillars at Karahan Tepe can vary. One fair-sized example, for instance, in Structure AH, located at the southern end of the current excavations, has eight digits. Why it should have eight fingers is unclear. Did this number have some symbolic meaning to the local community, or was it purely a case of sloppy workmanship on the part of the stone carver? There are no clear answers at present.

The side of the T-pillar displaying eight fingers in Enclosure AH has an additional, quite curious feature. It shows the figure’s articulated arm in raised relief with the shoulder joint clearly carved to resemble a bird’s head, almost certainly that of a vulture (see Fig. 16).

Figure 16. Broken T-pillar in Karahan Tepe’s Structure AH showing the shoulder joint of its articulated arm the head of a bird, almost certainly that of a vulture. Credit: Andrew Collins

The New Hilltop Enclosure

Beyond this structure on the top of the hill, excavations conducted in 2023 exposed the presence of an enormous enclosure as much as 33 meters (108 feet) in size (see Fig. 17). Aside from the usual stone benches and T-pillars, it was found to contain some unique features.

Set within the north-northeastern section of its retaining wall is a stone altar area framed by twin T-pillars that have lost their heads due to exposure above ground level. Centrally positioned above the altar is a circular porthole stone supported by drystone walling. At its center is a round hole similar to that found in connection with the various rectangular-shaped porthole stones seen at Göbekli Tepe. These holes almost certainly represent seelenloch, German for “soul holes,” through which the souls of the departed or those of shamans were seen to pass on their journey to and from the sky world.

On and around the altar three large stone platters were found. These had been left in situ before the installation was covered over by soil and rubble. At the altar’s eastern edge excavators found the statue of a standing vulture that faced into the enclosure (see Fig. 18). It is 58.5 centimeters (23 inches) in height and is almost cartoon-like in appearance, looking like an animated character from a Disney film!

Figure 18. The standing vulture statue found inside the hilltop enclosure at Karahan Tepe. Credit: Andrew Collins

On the eastern side of the vulture, set firmly within a stone bench, excavators uncovered a massive seated male human figure (see Fig. 19) broken into pieces, but afterwards reconstructed and placed back in position. It displays striking features, including an anatomically correct ribcage, a mullet-like haircut, and realistic facial detail. The man holds his penis with both hands as if emphasizing its importance. With a height of around 2.3 metres (7.5 feet), even in a seated position, the statue can be seen to represent an oversized individual. In other words, a giant. What this might imply is explored later.

Horizontal Alignment

What does this enclosure signify? Unlike the enclosures on Karahan Tepe’s lower slopes, no serpentine imagery has so far been found. What is of interest is the structure’s orientation, which targets the summit of a local hill towards the north-northeast called Ceylân Tepesi, meaning the “hill ridge (tepesi) of the gazelle (ceylân).” Since this is also the direction towards which the porthole stone faces, the chances are this was seen as the direction of the sky world.

Figure 19. The seated statue of a giant human figure found in the new enclosure recently exposed on the summit of Karahan Tepe. Credit: Andrew Collins

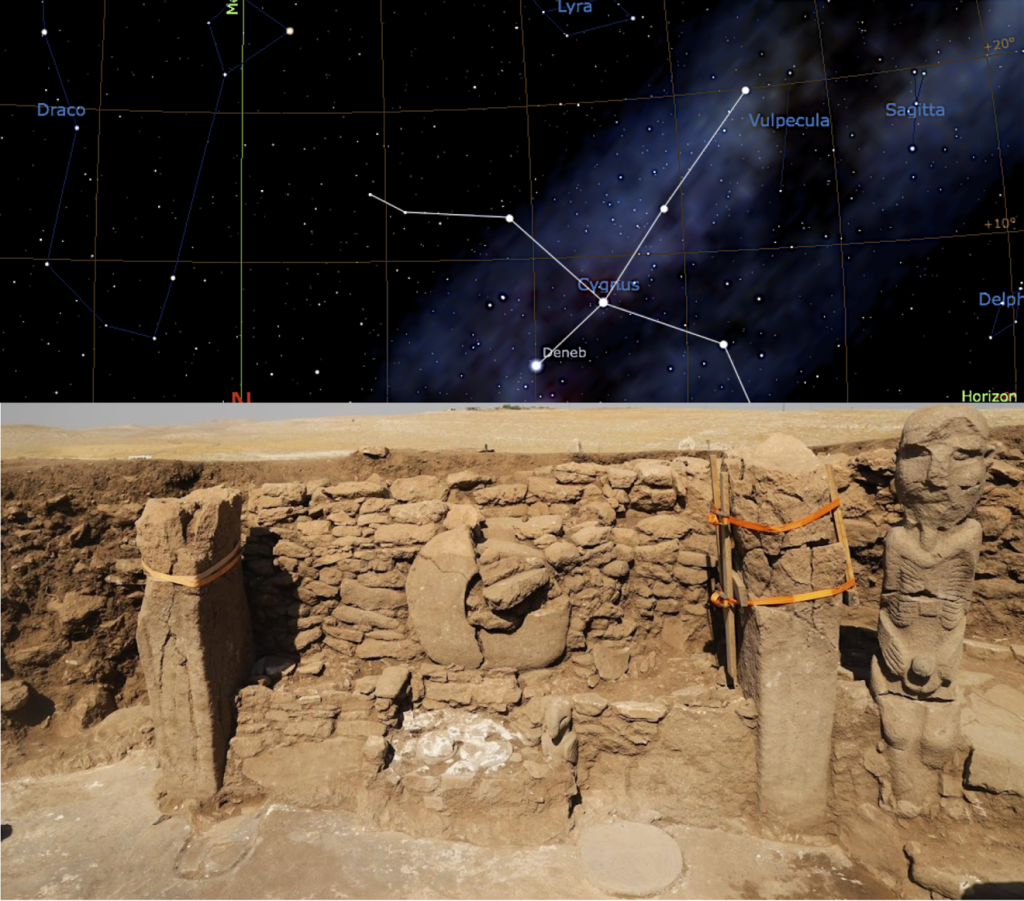

On the understanding that this newly exposed structure probably dates to circa 9000-8800 BCE, an examination of the free software program Stellarium shows that during the time frame in question, the bright star Deneb, in the constellation of Cygnus, would have been seen to rise up from the position of Ceylân Tepesi as viewed from the summit of Karahan Tepe (see Fig. 20).

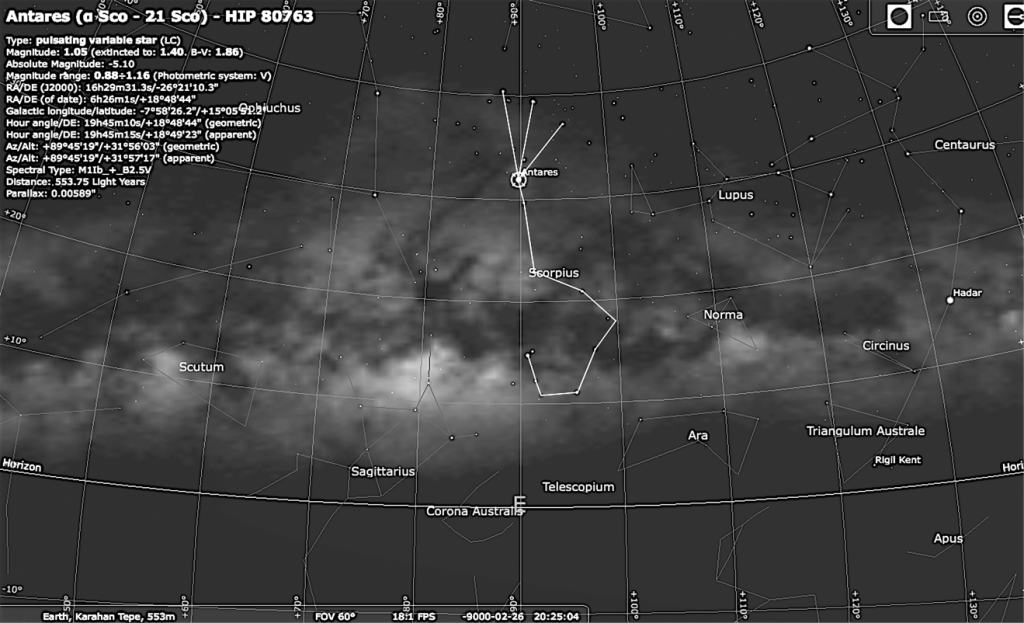

Deneb marks the northern opening of the Milky Way’s Dark Rift, which at this time would have been seen to stretch almost horizontally from Ceylân Tepesi right across to its southern termination in the vicinity of the Galactic bulge and stars of Scorpius. At this time, these two features would have been low in the eastern sky, somewhere between due east and 10 degrees south of east (see Fig. 21).

Figure 20. Stellarium view of the rising of Deneb in 9000 BCE as seen from the interior of the new enclosure on the summit of Karahan Tepe. Note the hill ridge known as Ceylân Tepesi immediately beneath the star Deneb. Credit: Stellarium/Andrew Collins

This matches very well the axial orientation of Karahan Tepe’s Structure AD (the Grand Ellipse) down on the lower level. At approximately 10 degrees south of east, it would have meant that anyone sitting on one of its rock-cut thrones could have witnessed both the Galactic bulge and the stars of Scorpius rise right in front of them. This would have been at the same time that anyone positioned in the newly exposed enclosure on the top of the hill could have watched the star Deneb and the northern opening of the Milky Way’s Dark Rift rise from Ceylân Tepesi in line with the structure’s own axial orientation.

Figure 21. Galactic Bulge and stars of Scorpius rising in the eastern sky circa 9000 BCE as viewed from the rock-cut thrones at the western end of Karahan Tepe’s Structure AD. Credit: Stellarium/Andrew Collins

Journey of the Soul

It should be pointed out that all these celestial objects—the star Deneb, the Milky Way’s Dark Rift, the Galactic bulge, and the stars of Scorpius—form part of a cosmological process centered around the Milky Way, which has long been seen as a path, road or river along which souls are able to reach the sky world. This can be seen, for instance, in the Native American death journey adopted by as many as 30 to 40 different tribal confederations. For them, the soul was expected to join the Milky Way via the constellation of Orion, or in some cases the star cluster known as the Pleiades, and then journey along the starry stream in its role as the Path of Souls until it reached the position of Deneb. It is at this point that the Milky Way bifurcates into two separate streams due to dust and debris in line with the Galactic plane. In this way, Deneb acted as a hole or portal permitting the soul access to the afterlife.[8]

Almost exactly the same journey of the soul is found in the ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts dating to circa 2350 BCE. In these, the soul of the pharaoh, in its guise as Osiris, the god of the dead or the god that is dead, after exiting the duat-underworld was expected to climb towards the stars of Orion before continuing along the Milky Way towards the welcoming embrace of his sky mother, Nuit. It was within her womb, marked by the stars of Cygnus, that the pharaoh was reborn into the afterlife.[9] It is worth pointing out here that in Mayan cosmology, the Milky Way’s Dark Rift was seen as the Road to Xibalba [the “Black Road”], the name given to the underworld (see Fig. 22).[10]

Figure 22. The Milky Way’s Dark Rift was seen by many ancient cultures as a pathway or bridge to the sky world. Public domain

The Vulture as Psychopomp

In the ancient sky lore of Anatolia and the Near East, the stars of Cygnus were identified with a great bird associated with the soul’s death journey. In Sumerian, ancient Hellenic and Armenian sky lore this bird was seen in terms of a vulture or a shaman in the form of a vulture. Even in Armenia today, the stars of Cygnus form a sky figure known as Angegh, the vulture. Since the kingdom of Armenia formerly included much of southeastern Anatolia (including Göbekli Tepe, which Armenians refer to as Portasar, meaning the “hill of the navel”), there seems every reason to suspect that some aspects of Armenian sky lore originated among the descendants of Taş Tepeler.

The reason why the soul bird of Anatolian and Near Eastern sky lore was a vulture is because of the bird’s involvement in the process of sky burial, where human cadavers are exposed on elevated surfaces, allowing the great birds to swoop down and devour their flesh. It is a practice that Professor Klaus Schmidt, the rediscoverer of Göbekli Tepe, felt had taken place at the site.[11] The bird’s involvement in sky burials led to the vulture becoming the primary symbol of death and resurrection during the early Neolithic age.

The vulture, of course, features prominently on Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 43 (see Fig. 23). On this, we see one large central vulture with its wings open alongside which is a juvenile vulture. A third vulture is seen on the pillar’s stem. This carries a headless man, suggesting it is acting in the capacity of a psychopomp, a “guide of souls,” or “soul carrier” from the Greek psyche, “soul,” and pompos “conductor.” It was the psychopomps’s role to carry the human soul from the material world to the sky world, or, of course, vice versa, from the sky world to the realm of physical existence.

Figure 23. Göbekli Tepe’s enigmatic Pillar 43. Is it the world’s oldest calendar or a pictorial aid for shamans and initiates wishing to access the sky world? Credit: Andrew Collins

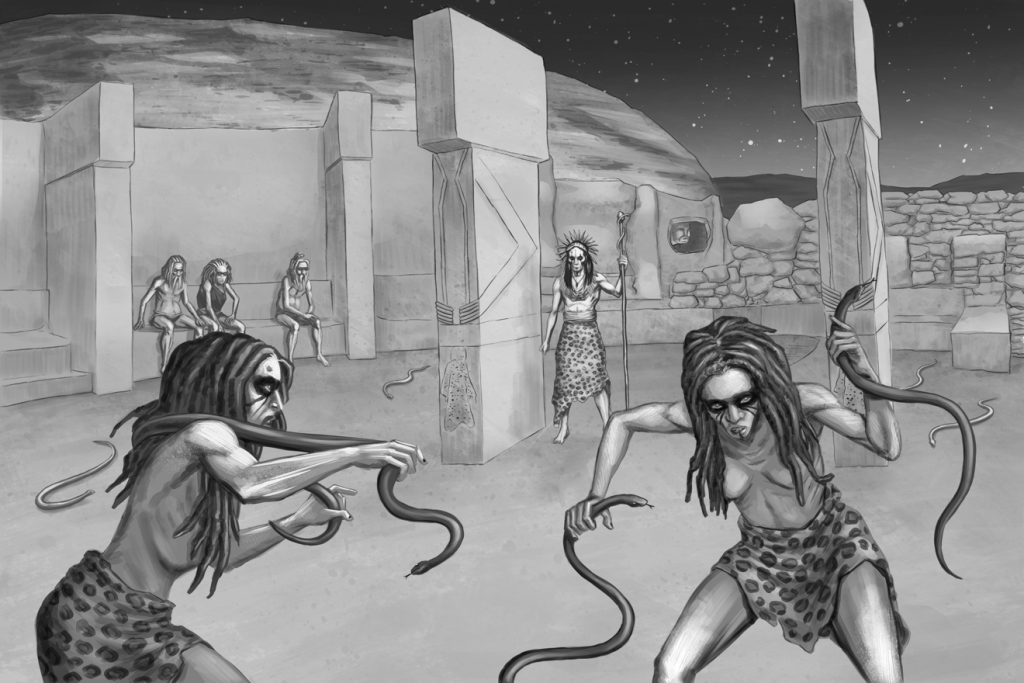

Serpent Spirit

If among the Taş Tepeler inhabitants of southeastern Turkey, the stars of Cygnus were identified as a celestial vulture, then what about the Galactic bulge and stars of Scorpius? What did they represent? Although the scorpion seen on Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 43 has been identified, probably correctly, as a representation of the Scorpius constellation [12], in the sky lore of various ancient cultures, this same group of stars, or some of them at least, was identified as a snake. The fact that in Greek sky lore, the asterism immediately above Scorpius is Ophiuchus, the serpent holder or snake charmer, adds weight to the idea that somewhere in this area of sky, the ancients recognized the presence of a sky figure in the form of a great snake. (Ophiuchus, by the way, has been identified as the thirteenth sign of the zodiac, an extraordinary claim examined in Karahan Tepe: Civilization of the Anunnaki and the Cosmic Origins of the Serpent of Eden).

In the knowledge that the stars of Scorpius might well have been seen in terms of a celestial snake, can we go on to identify the role of the Galactic bulge seen next to it? In past ages, this bulge, which marks an active area of star formation close to the center of the Milky Way galaxy, would have seemed like a celestial light bulb,[13] something that would have been difficult to ignore.

The World-encircling Snake

In the opinion of the present author, the Galactic bulge was seen as the head of a great serpent identified with the entire length of the Milky Way (see Fig. 24). This, of course, completely surrounds the Earth and was seen to rise and fall every night of the year.

The stars of Scorpius, I suspect, signified not only the celestial serpent’s forked tongue, but also its active spirit. Seen to arch across the sky from horizon to horizon, the Milky Way was considered a world-encircling serpent biting its own tail in many ancient traditions. The most obvious artistic expression of this symbolism is, of course, the Ouroboros of Greco-Egyptian tradition (see Fig. 25), although similar ideas of a world-encircling snake identified with the Milky Way can be found in Native American, Vedic, Greek, and Akkadian sky lore.

More important to this debate, perhaps, is the fact that the Yezidi peoples of Lake Van in eastern Anatolia recognized the existence of a world-encircling serpent that forever chased its own tail. If soever its head was to catch up with its tail, the end of the world would surely follow (Khanna Omarkhali, pers. comm.).

Quite separately, the Yezidi venerate the black snake as a symbol both of godhead and as an expression of their animistic and even shamanistic beliefs in the power of the snake (see Fig. 26). This brings us back to what might have been going on at Karahan Tepe as much as 11,000 years ago. If the above speculations are correct, then it seems likely that the site’s Taş Tepeler inhabitants venerated the Galactic bulge as the head of a celestial snake (see Fig. 27), making sense of why so much serpentine symbolism has been found there. It also makes sense why two out of three of its interconnected bedrock structures would appear to have been designed to resemble the head of a snake, this being to enable one-to-one communication with its celestial counterpart. It was, of course, towards this particular area of the sky that Karahan Tepe’s Great Ellipse (Structure AD) faced each night.

Figure 26. The black snake of Yezidi tradition seen in an open air sanctuary in the village of Mağaraköy (Kurdish: Kiweh or Kiwex) located in the İdil district of Şırnak province, southeastern Turkey. Credit: Andrew Collins

Was the giant human head with its serpentine neck inside the Pillars Shrine itself an expression of the Galactic bulge’s role as the head of the cosmic serpent? Would this speak to the supplicant whilst they were in an altered state of consciousness? Did the curved serpentine pillar standing at the center of the same room signify both the tongue and the active spirit of the celestial serpent? By pouring water into the Pillars Shrine, were its Taş Tepeler inhabitants attempting to create the right environment for these communications to take place? If the deep pit within the neighboring Pit Shrine (Structure AA) was also meant to contain water, did this second snake-themed edifice function as a form of cosmic environment within which the cosmic serpent was thought to exist?

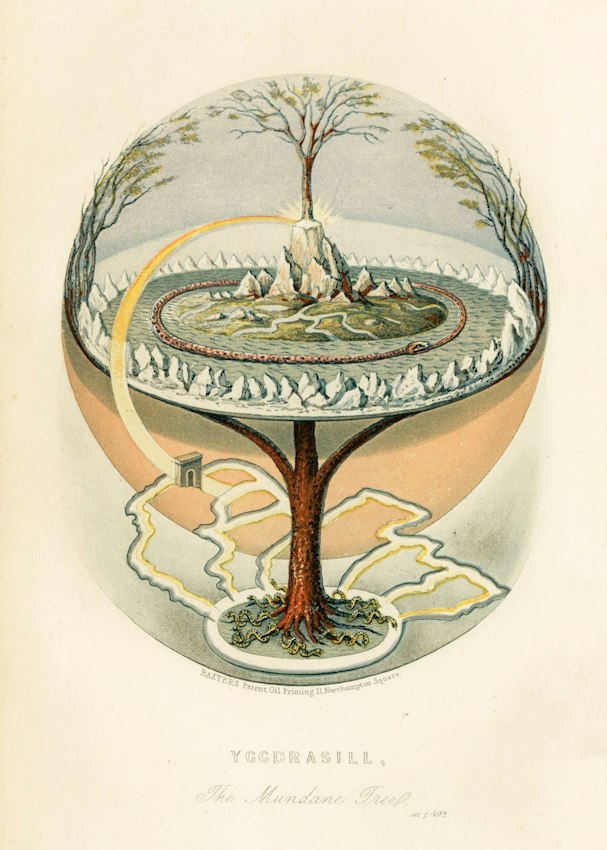

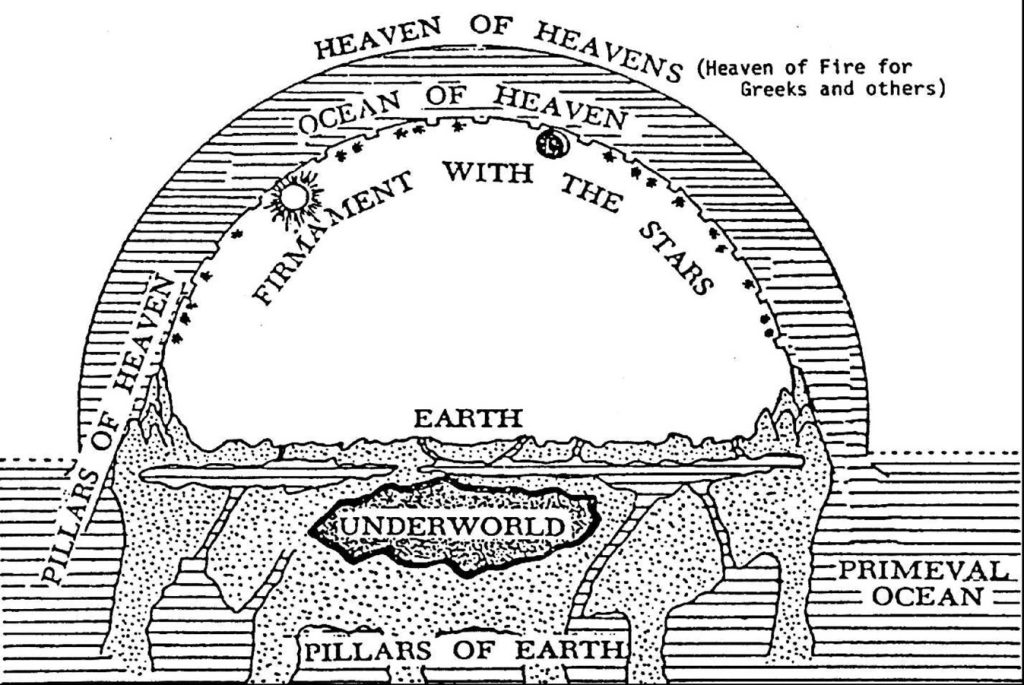

The world-encircling serpent was thought to dwell in a primeval realm known as the cosmic ocean. This was considered to exist outside the physical universe, which was itself divided up into three separate “worlds.” This division of the cosmos can be found, for instance, in Norse mythology, where the world serpent Jörmungandr was thought to exist in the cosmic ocean surrounding Middle World (see Fig. 28). At the center of the Middle World was Yggdrasil, the World Tree, that formed the cosmic axis linking together all three worlds—the Upper World (or sky world), the Middle World (Midgard), and the Lower World (or underworld), the last of which was thought to exist beneath the earth.

Figure 28. The Yggdrasil of Norse mythology with the Midgard Serpent seen encircling the Middle World in the cosmic ocean. Public domain

Similar concepts of a three-tiered cosmos can be found across the globe, from the beliefs of Native Americans to the Saami peoples of Scandinavia, and the Finno-Ugric populations of northern Europe, all have similar cosmogonic myths, suggesting that they share a common origin. If so, then this would explain why the cosmological symbolism of Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 43 alludes to the manner in which a three-tiered existence emerged from a primordial chaos imagined in terms of a primeval ocean. This seems expressed by the three lines of chevrons occupying the highest part of its T-shaped termination. These, I believe, represent the flow of water within the cosmic ocean. Placed between the first and second rows of chevrons are three devices popularly referred to as “manbags.” This is due to their resemblance to the “bags” held in the hands of ancient figures shown in ancient art around the world.

Although to some, these “manbags” can be seen as stash bags containing hallucinogens to help the shaman or initiate attain altered states of consciousness, a more likely explanation in the case of Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 43, is that they represent the three worlds, with the Upper World on the left, the Middle World at the center, and the Lower World on the right-hand side (see Fig. 29).

Figure 29. The head of Pillar 43 showing its three “manbags,” which most likely represent the three worlds situated within the cosmic ocean. Credit: Andrew Collins

The worlds themselves are signified by the rectangular “bags,” while the “handles” (which in all three cases are offset to the left and so could not have functioned as actual bags) show their celestial vaults (see Fig. 30 for an example how the celestial vault is thought to exist within the cosmic ocean).

To the right of each of the “manbags” is a small creature. This, I am convinced, represents the animistic influence of each of the three worlds. Next to the lefthand “bag” is a wader bird, arguably a species of crane, stork, or flamingo, representing the Upper World. The choice of wader bird was no doubt due to its ability to stand within the celestial waters of life.

Next to the middle “manbag” on Pillar 43 is a leopard symbolizing the Middle World. This animal was seen not only as a psychopomp able to leap between worlds, but also as the force of the earth itself. Finally, next to the “handle” of the “manbag” on the right-hand side is a frog or toad representing the Lower World. In Eurasian folklore the toad was recognized as a denizen of the underworld and as a creature of transformation.[14] Interestingly, all the animals chosen to represent the three worlds can exist on land, in water, and also in the air (even leopards, which are good swimmers and can make huge leaps through the air). This makes all three animistic forms perfect symbols of the soul’s transmigration to and from the sky world and cosmic ocean.

The Primordial Chaos

Below the pillar’s three “manbags” on Pillar 43 is a line of squares that pass between the second and third row of chevrons. In the current author’s opinion, these squares, which connect the head of the vulture on the left to the neck of a large wader bird on the right, symbolize a bridge permitting human souls, either those of the dead or those of shamans, to transit from this world to the place of the afterlife, where life emerges from in the first place. It was within these cosmic waters that the world-encircling snake was also thought to dwell, making sense of why the snake-themed shrines at Karahan Tepe might have acted as plunge pools enabling supplicants to immerse themselves entirely in water and thus achieve one-to-one communications with the active spirit of the world-encircling serpent.

In the Mesolithic and Neolithic art of ancient Anatolia, a carved circle symbolized the soul of an individual,[15] which can be seen on Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 43 above the main vulture’s left wing. Its presence symbolized the soul’s imagined journey across the stepping stone bridge, where it was received by the wader bird, symbolizing entry into the sky world beyond which lay the cosmic ocean.

Ethereal bridges of this kind exist in the mythologies of various ancient cultures and contemporary religions. In Norse tradition, for instance, it is synonymous with Bifröst, the Rainbow Bridge that leads from Midgard to Asgard, the realm of the gods, while in Zoroastrian tradition, it is the Chinvat Bridge that the souls of the departed have to take in order to reach heaven. In Islamic tradition, it becomes As-Sirat, the bridge over which the righteous will have to cross on their way to paradise. Similar bridges stretching between this world and the afterlife are also to be found in Native American tradition.

The carved imagery of Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 43, along with the various installations uncovered to date at Karahan Tepe, would thus appear to reflect a deep understanding of cosmogonic realities considered by the region’s Taş Tepeler inhabitants to exist beyond physical existence—realities that were accessible to the human soul either through death or through the achievement of altered states of consciousness. Every symbol it bears acted as a mnemonic teaching device for shamans and initiates wishing to access the three worlds beyond which lay the waters of life itself. The fact that these cosmogonic notions would also appear to have existed in parallel in other parts of the ancient world, and arguably even on the American continent, suggests a common point of origin going back more than 12,000 years to the Paleolithic age. The potential genesis point of all these ideas will be examined shortly.

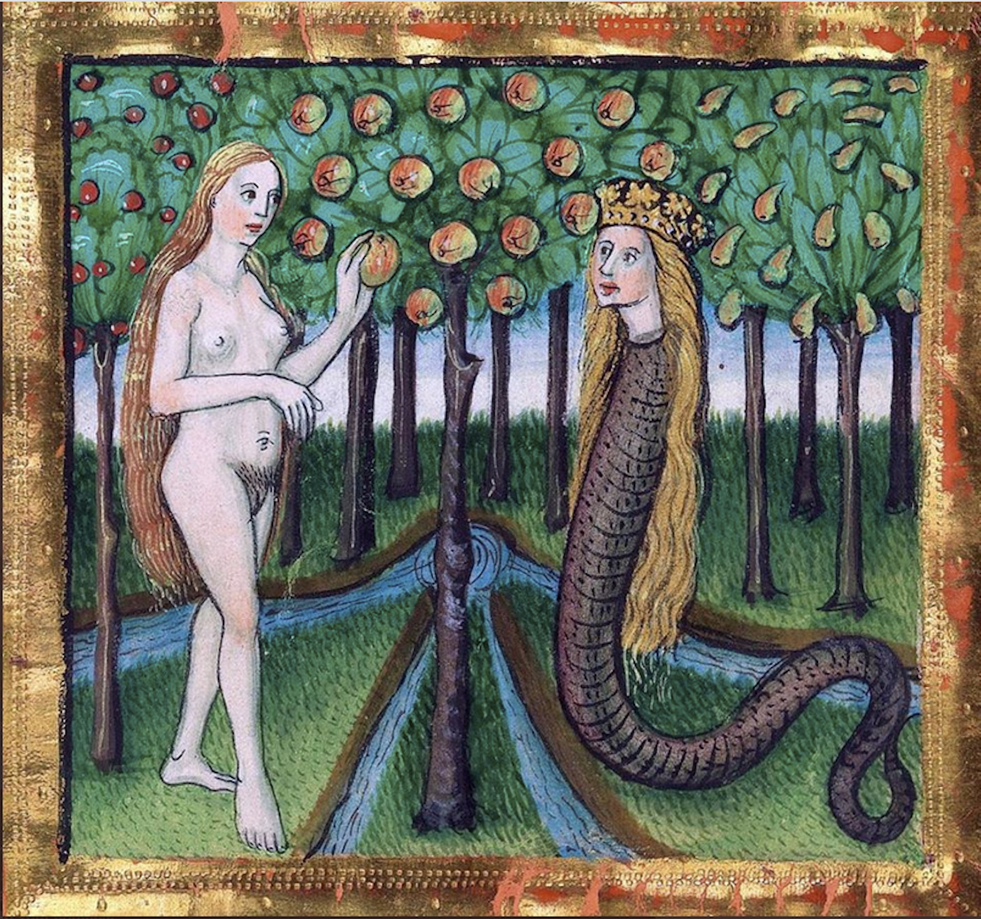

In the Garden of Eden

There can be little question that various firsts for humankind emerged from the region of southeastern Anatolia during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic age, which began around 11,600 years ago. This included the first animal husbandry, the first widescale employment of domesticated cereal crops, the earliest production of wine and beer, the first ceramic figurines, the earliest use of beaten copper and woven fabric, as well as the first construction of rectilinear buildings and monumental architecture at sites such as Göbekli Tepe and Karahan Tepe.

It is perhaps not surprising then that in myths recounted even today in the city of Şanlıurfa (known as Edessa in the Bible), located just 14.5 kilometers (9 miles) away from Göbekli Tepe, speak of it being the true site of the Garden of Eden.[16] Indeed, one of the city’s most archaic names is Adamah, meaning the “place of Adam,” while another is el-Ruha, Aramaic for “the soul.” The soul in question is that of Adam, which was first placed down on earth in Şanlıurfa, where God then used the local red earth to create his physical body.

It is in the Garden of Eden, according to the book of Genesis, that the Serpent of Eden tempted Adam and Eve into partaking of the forbidden fruit, allowing them to open their eyes and realize that they were naked (seen in terms as the loss of innocence) (see Fig. 31). For their sins God cast the First Couple out of the terrestrial paradise and, in the stories told in Şanlıurfa, they journeyed eastwards and settled on the nearby Harran plain. There, they invented agriculture and grew the first cereal crops using a stalk of wheat that Eve had brought out of the Garden of Eden.[17] Are such stories abstract memories of the domestication of wheat by the region’s Taş Tepeler inhabitants some 10,500 years ago?

If so, then who or what was the Serpent of Eden? What might this beguiling creature, so reviled by the Abrahamic faiths, actually represent? Could it be an abstract memory of the Taş Tepeler community’s reverence of the cosmic serpent? This was something that presumably involved shamanic communications with its head and active spirit, identified, as we have seen, with the Galactic bulge and stars of Scorpius, the latter of which also probably represented the serpent’s forked tongue. Perhaps not unconnected is the fact that the expression “speaking with a forked tongue,” said of those who spread falsities and lies, is popularly thought to derive from the manner the Serpent of Eden deceived Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden.[18]

Was this tradition just a highly abstract memory of Taş Tepeler’s believed communications with the Milky Way serpent carried across countless generations until, eventually, it manifested as a myth within the earliest precursors of the Abrahamic faiths?

It was towards the Galactic bulge in its roles as the head of this cosmic serpent that Karahan Tepe’s easterly-oriented Great Ellipse (Structure AD) would appear to have been directed. What this suggests is that any rites associated with this area of sky would have taken place as both the Galactic bulge and stars of Scorpius rose into the eastern sky. Most obviously, this occurred on the night of the winter solstice, making sense of why the giant stone head inside the Pillars Shrine was illuminated by a dart of light for some 45 minutes shortly after dawn on this day. This was a discovery made by my colleagues Hugh Newman and J.J. Ainsworth in December 2021, the breathtaking account of which appears as an appendix in Karahan Tepe: Civilization of the Anunnaki and the Cosmic Origins of the Serpent of Eden. Did the activation of this enormous stone head signal the arrival of the cosmic serpent? Would it have spoken to those who came before it at this time in the same manner that the Serpent of Eden spoke to Adam and Eve?

It should be mentioned that an alignment between Karahan Tepe’s snake-themed Pit Shrine (Structure AA) and both the setting sun at the time of the summer solstice in 9000 BCE and, just two and half hours later, the appearance at the same place on the horizon of the Galactic bulge had earlier been discovered by the present author. Indeed, it was for this reason that Hugh and J.J. had gone to Karahan Tepe on the winter solstice to see whether any similar alignments might occur then.

Rise of the Anunnaki

This now brings us to the subject of the Anunnaki, the very human gods of the Sumerians, Akkadians and later Babylonians, who, from their home within the Duku mound, were said to have given humanity “sheep and grain” as sustenance. It is popular today to see the story of the Anunnaki as recording the arrival on earth of space beings who either created or genetically modified our human ancestors to mine gold in South Africa that was afterwards taken to their home planet, Nibiru.

In the opinion of Klaus Schmidt, the Anunnaki were the prime movers behind the foundation of Taş Tepeler, the Duku mound being a memory of Göbekli Tepe itself, with the “sheep and grain” given to mortal kind being an inference to the invention of animal husbandry and cereal cultivation.[19]

Schmidt proposed that the huge, anthropomorphic T-pillars found at the center of the enclosures at Taş Tepeler sites were considered the living spirits of divine ancestors remembered under the name Anunnaki,[20] a term derived from the Sumerian Anunna, meaning “[people] of the sky” or, simply, the “sky people.”[21] I strongly suspect that Schmidt was correct in his surmise that the Anunna or Anunnaki were the prime movers behind the foundation of Taş Tepeler some 12,000 years ago.

Where exactly these very terrestrial gods, these presumably flesh and blood beings, might have come from is something I have examined in detail in various books.[22] By far, the best evidence as to their origins, however, is that their incursions into Anatolia had begun far to the north, on the Eurasian steppe, their migrational journey having begun as far east as Siberia and Mongolia as much as 30,000-40,000 years ago. This, as we see next, is an opinion now being championed by certain members of the Turkish archaeological community.[23]

The Siberia-Göbeklitepe Hypothesis

At an important archaeological congress held in Istanbul in June 2022, Semih Güneri, a retired professor from the Caucasian and Central Asian Archaeology Research Center of Dokuz Eylül University, and his colleague, Professor Ekaterine Lipnina, presented what they referred to as the Siberia-Göbeklitepe hypothesis. This proposes that the prime movers behind the emergence of Göbekli Tepe’s advanced culture were the descendants of human groups whose migrational journey had begun in Siberia and Mongolia around 30,000 years ago. They base their conclusions on a careful study of the evolution of microlithic tools used by Taş Tepeler, along with DNA evidence coming from human remains belonging to the Epipaleolithic inhabitants of the Zagros Mountains in what is today Iran.[24]

Legacy of the Denisovans

What then might have been going on in Siberia and Mongolia as much as 30,000-40,000 years ago to trigger a series of migrations north and south of the Ural Mountains into, respectively, northern Europe and southwestern Asia? The answer probably lies in the sudden emergence in Siberia and Mongolia of advanced technologies and innovation as much as 45,000-50,000 years ago. At occupational sites like the Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains of Siberia and settlements like Tolbor-16 in northern central Mongolia [24], the first anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) to reach these regions would have encountered a mysterious ancient cousin, a type of archaic human, known as the Denisovans (pronounced Dee-nis-o-vans).[25] They shared a common ancestry with the Neanderthals, although both these branches of humanity, along with our own Homo sapiens ancestor (Homo antecessor), probably had a shared origin in a type of hominin known to science as Homo heidelbergensis. They inhabited both the African and Eurasian continents from around a million years ago down to about 300,000 years ago.

The Siberian Denisovans (as opposed to their southern counterparts, the Sunda Denisovans, who inhabited southeastern Asia and Island Southeast Asia) would seem to have achieved incredible advances in technology and innovation. This included the manufacture of sophisticated jewelry (look up the Denisovan bracelet and see Fig. 32) and the making of the first bone needles (used probably to make tailored clothing).[26]

They also created the principal tool kit that became standard during the Upper Paleolithic age, and even produced some of the first musical instruments (in the form of a bone flute or whistle found in the Denisova Cave and thought to be as much as 45,000 years).[27] It is also considered possible that the Denisovans lived alongside an indigenous species of horse and may, just may, have domesticated and ridden them (this evidence coming from the presence of horse DNA found inside the Denisova Cave).[28]

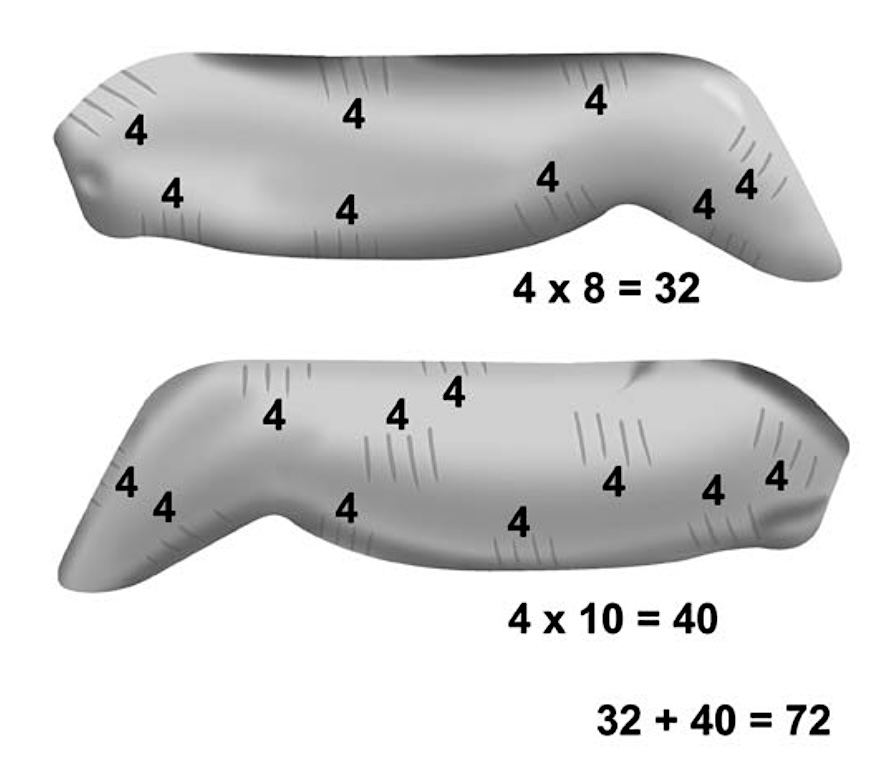

Lastly, there is tantalizing evidence that the Denisovans developed an interest in certain key numbers derived from a basic understanding of the cyclic movement of the sun and the moon. This was the author’s conclusion following an examination of a mammoth ivory figurine of a cave lion found inside the Denisova Cave. It has a series of notches on each side of its body, with 8 groups of 4 on one side, making a total of 32 notches, and 10 groups of 4 on its other side, making a total of 40 notches. Together, this provides a grand total of 72 notches [29] (See Fig. 33).

Figure 32. Denisovan bracelet found in the Denisova Cave and thought to be around 45,000 years old. Credit: Nick Burton

Figure 33. The mammoth ivory figurine of a cave lion found in the Denisova Cave showing its 72 notches in 18 groupings of 4. Is this our first indication of the autistic mindset of the Denisovans, something passed on to their Denisovan-anatomical modern human descendants? Credit: Nick Burton/Andrew Collins

The number of notches involved could, of course, simply be random, without any real meaning. This, however, seems unlikely, with 72 (4 x 18) being an auspicious number that occurs again and again in ancient cosmologies. In addition to this, the number of notches on each side of the figurine also seem to have been chosen with a specific purpose in mind since 32 is 4 x 8 while 40 is 5 x 8.

As mentioned in connection with the T-pillars that stood in a circle within Karahan Tepe’s Great Ellipse (Structure AD), 18 years is a figure very much associated with long-term lunar cycles and eclipse cycles, while 72 years is one degree of a processional cycle as well as the length of a human life cycle in Siberian and Mongolian shamanic tradition.[30] Eight years, on the other hand, is the length of time it takes for the planet Venus to return back to the same position in the sky. Thus, a Venus “year” is equal to 8 earth years, meaning that 32 years and 40 years—numbers inferred by the division of the 72 notches on the cave lion figurine—can be seen as multiples of this same cycle.

All this suggests that the Denisovans were familiar with the cyclic motion of the heavens as much as 45,000 years ago. What is more, these interests in calculating long-term time cycles became more and more complex among their descendants (see, for instance, the 24,000-year-old mammoth bone plaque found at the archaeological site of Mal’ta in the Transbaikal region of Siberia, a topic explored in my book The Cygnus Key [2018]).

Why the Denisovans developed mental notions more complex seemingly than their cousins, the Neanderthals, or indeed the first anatomically modern humans to reach Siberia and Mongolia, could well be down to genes passed on from them to our own earliest ancestors. They include two genes (ADSL and CNTNAP2), which are both considered to trigger autism in our own species.[31] In the knowledge that these genes presumably functioned in a similar way among the Denisovans makes it clear that they, too, probably possessed an autistic mindset that included savant-like qualities. This might have included calendar counting and the ability of autistic people to be able to know what day of the week any date in the future falls.

Today, such skills might be viewed as a novelty. In the past, however, what we see as calendar counting could have been used to predict the movement of the sun, the moon and even the planets. Dr. Darold Treffert, Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine, is a world-renowned expert on savant skills and was a consultant for the 1988 film Rain Man, featuring an autistic character played by Dustin Hoffman. Treffert has had this to say about the origins of calendar counting: “Could it be possible that the calendar calculating ‘chip’ [among savants] is derived inanely from the predictable and constant rhythm of the sun and moon passed on through generations via genetic memory?”[32]

If Treffert is correct, then calendar counting as a skill probably dates back to the Siberian Denisovans of the Altai Mountains. Not only can this explain the presence of auspicious numbers in carved art, but it also helps explain the existence of many ancient mythological traditions of complex numerological systems based on long-term time cycles.[33]

The unique mindset of the Siberian Denisovans would appear to have been inherited by their hybrid descendants, who in turn carried the legacy of the Denisovans to other parts of the ancient world, including southwestern Asia, Europe and even the American continent. This legacy, I suspect, included fully fledged cosmogonic notions like those found both in northern Europe and among the Taş Tepeler inhabitants of southeastern Anatolia. In other words, the carved relief seen on Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 43, along with the design and function of Karahan Tepe’s snake-themed shrines, might well derive from cosmogonic notions that originated as far east as Siberia and Mongolia as much as 30,000-40,000 years ago.

From the Denisovans to the Anunnaki

What meager evidence we have of Denisovan physiognomy suggests they were of enormous size, comparable with the largest WWE wrestlers or American footballers of today. These physical traits were likely passed on to their hybrid descendants, meaning that they, too, were probably tall and robust. Are such oversized individuals represented by the great stone monoliths at places like Göbekli Tepe and Karahan Tepe? Might this explain the presence of the giant human statue found in the newly discovered structure located on the summit of Karahan Tepe? Is this our first real glimpse of what the Anunnaki truly looked like? I am convinced the answer is “yes.”

The original Sumerian term for Anunnaki was Anunna, which, as previously mentioned, can be translated as “[people] of the sky” or, simply, the “sky people.” Although some might interpret this as demonstrating that the Anunnaki came from the sky, for me, it has a different meaning. Is it possible that the term Anunna refers not to space beings but to those with knowledge of the sky, in other words, shamans or shamanic-based societies with a profound understanding of the influence on the world of the sun, moon and stars?

To me the Anunnaki were not just the founders of Taş Tepeler—they were the first astronomers as well as the first astrologers. It would be through their influence that the earliest Pre-Pottery Neolithic settlements were established in southeastern Anatolia. Although many of these were subsequently buried beneath earthen mounds, or tepes, others would thrive to become major cities. They included Şanlıurfa and Harran, both of which would eventually become home to the Chaldean astrologers and astronomers. Their knowledge and wisdom would go on to inspire the emergence of Ophite Gnosticism, which spread like wildfire across Anatolia and the Near East in late antiquity.

The Ophites believed in Gnosis, a state of oneness with the divine involving the existence of a demiurge, a creator of the physical world, in the form of a celestial serpent. What is so incredible is that this is likely the same cosmic serpent that thousands of years earlier was venerated by the Taş Tepeler inhabitants of places like Göbekli Tepe and Karahan Tepe, almost certainly for the purposes of attaining communication with an intelligence corresponding with the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy.

These are just some of the topics discussed in Karahan Tepe: Civilization of the Anunnaki and the Cosmic Origins of the Serpent of Eden by Andrew Collins (Vermont, VN: Inner Traditions in 2024.

For more information, go to https://www.innertraditions.com/karahan-tepe

See also Andrew’s website www.andrewcollins.com 1

Notes and References

[1] See Çelik 2000, Çelik 2011, Çelik 2014, and Collins 2014a.

[2] Karul 2021, Karul 2022.

[3] Karul 2021, 23–24.

[4] Karul 2021, 24.

[5] Karul 2021, 25.

[6] Karul 2021, 25.

[7] Karul 2021, 21.

[8] See Little and Collins 2014 for a full treatment of this subject.

[9] For more information on these topics, along with all primary reference sources, see Collins 2004, Collins 2014b, Collins 2018, as well as Little and Collins 2014.

[10] Tedlock 1996, 356. See also Jenkins 1998, 10–11, 13, 61, 106, 117.

[11] Schmidt, 2012, 131–2.

[12] Belmonte 2010.

[13] Bender 2022.

[14] Engeling 2017, 320 fn. 23.

[15] Uyanik 1974, 12.

[16] Açıkgenç and Ekinci 2017, 189-190.

[17] Açıkgenç and Ekinci 2017, 189-190.

[18] See, for instance, “Speak with a forked tongue” 2018.

[19] Schmidt 2012, 206–7.

[20] Schmidt 2012, 206–7.

[21] Falkenstein 1965.

[22] See Collins 1996, Collins 1998, Collins 2006, Collins 2014b, Collins 2018, Collins 2020, and Collins 2022.

[23] “Migration from Siberia behind formation of Göbeklitepe” 2022

[24] Holder 2019.

[25] Zwyns et al 2019.

[26] “World’s Oldest Needle Found in Siberian Cave that Stitches Together Human History” 2016.

[27] Lbova, Kozhevnikov, and Volkov 2012, CD-1902.

[28] See, for instance, “Genome of Horse Linked to Extinct Human Species Decoded in Russia” 2013, and “DNA Deciphered of Horse Used by Extinct Humans” 2013.

[29] Collins 2019.

[30] Shodoev 2012, 61–4, 67.

[31] Lauerman 2012; Meyer et al 2012.

[32] Treffert 2010, 66.

[33] Collins 2018, ch. 36–37.

Bibliography

Açıkgenç, Alparslan, and Abdullah Ekinci (eds.). 2017. Şanlıurfa: The City of Civilizations Where the Prophets Met. Istanbul, Turkey: Albukhary Foundation/KUM Publishing.

Belmonte, J. A. 2010. “Finding Our Place in the Cosmos: The Role of Astronomy in Ancient Cultures.” Journal of Cosmology 9: 2052–62.

Bender, Herman. 2022. “A Serpent’s Tale: The Milky Way.” Researchgate website.

Çelik, Bahattin. 2000. “A New Early-Neolithic Settlement: Karahan Tepe.” Neo-Lithics 2–3/00: 6–8.

———. 2011. “Karahan Tepe: a new cultural centre in the Urfa area in Turkey.” Documenta Praehistorica 38: 241–53.

———. 2014. “Differences and similarities between the settlements in Şanlıurfa Region Where ‘T’ Shaped Pillars Are Discovered.” Turkish Academy of Sciences Journal of Archaeology 17: 9–24.

Clottes, J. (dir.). 2012. L’art pléistocène dans le monde / Pleistocene art of the world / Arte pleistoceno en el mundo Actes du Congrès IFRAO, Tarascon-sur-Ariège, septembre 2010—Symposium « Datation et taphonomie de l’art pléistocène, LXV-LXVI, 2010–2011, CD and book. Tarascon-sur-Ariège, France: Société Préhistorique Ariège-Pyrénées.

Collins, Andrew. 1996. From the Ashes of Angels: The Forbidden Legacy of a Fallen Race. London: Penguin.

———. 1998. Gods of Eden: Egypt’s Lost Legacy and the Genesis of Civilization. London: Headline.

———. 2006. The Cygnus Mystery: Unlocking the Ancient Secret of Life’s Origins in the Cosmos. London: Watkins Books.

———. 2014a. “Karahan Tepe: Göbekli Tepe’s Sister Site—Another Temple of the Stars?” Academia.edu website.

———. 2014b. Göbekli Tepe: Genesis of the Gods. Rochester, VT.: Bear & Company.

———. 2018. The Cygnus Key. Rochester, VT: Bear & Company.

———. 2019. “45,000-year-old Cave Lion Figurine Uncovered At Denisova Cave.” Ancient Origins, November 20, 2019.

Collins, Andrew, and Gregory L. Little. 2020. Denisovan Origins. Rochester, VT.: Bear & Company.

———. 2022. Origins of the Gods. Rochester, VT.: Bear & Company.

“DNA Deciphered of Horse Used by Extinct Humans.” 2013. Sputnik News website, July 31, 2013.

Engelking, Anna. 2017. The Curse—On Folk Magic of the Word (trans. Anna Gutowska). Warsaw, Poland: Institute of Slavic Studies, Polish Academy of Sciences.

Falkenstein, A. 1965. “Die Anunna in der sumerischen Überlieferung.” In Güterbock and Jacobsen 1965: 127–140.

“Genome of Horse Linked to Extinct Human Species Decoded in Russia.” 2013. UPI website, July 31, 2013.

Güterbock, Hans G. and Thorkild Jacobsen (eds.). 1965. Studies in Honor of Benno Landsberger on his Seventy-fifth Birthday, April 21, 1963. Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press.

Holder, Kathleen. 2019. “Humans Migrated to Mongolia Much Earlier Than Previously Believed.” UC Davis website, August 16, 2019.

Hurriyet. 2022. “Migration from Siberia behind formation of Göbeklitepe.” Hurriyet Daily News website, June 28, 2022.

Jenkins, John Major. 1998. Maya Cosmogenesis 2012. Rochester, VT.: Bear & Company.

Karul, Necmi. 2021. “Buried Buildings at Pre-Pottery Neolithic Karahantepe.” Türk Arkeoloji ve Etnografya Dergisi 82: 21–31.

Karul, Necmi. 2022. “Şanlıurfa Neolitik Çağ Araştırmaları Projesi: Taş Tepeler /2022.” Journal of Archaeology & Art (Arkeoloji ve Sanat) 169 (January–April 2022): 7–8.

Lauerman, John. 2012. “Ancient Human Kin’s DNA Code Illuminates Rise of Brains.” Bloomberg UK website, August 30, 2012.

Lbova, Liudmila, Darya Kozhevnikov, and Pavel Volkov. 2012. “Musical Instruments in Siberia (Early Stage of the Upper Paleolithic).” In Clottes 2012: CD-1900 to CD-1904.

Little, Greg, and Andrew Collins. 2014. Path of Souls: The Native American Death Journey (preface and afterword by Andrew Collins). Memphis, TN.: Eagle Wing Books.

Meyer, M., M. Kircher, M. T. Gansauge, H. Li, F. Racimo, S. Mallick, J. G. Schraiber,

F. Jay, K. Prüfer, C. de Filippo, et al. 2012. “A High-Coverage Genome Sequence from

an Archaic Denisovan Individual.” Science 338, no. 6104 (October 12): 222–26.

“Migration from Siberia behind formation of Göbeklitepe.” 2022. Hurriyet Daily News website, June 28, 2022.

Schmidt, Klaus. 2012. Göbekli Tepe: A Stone Age Sanctuary in South-eastern Anatolia, Berlin, Germany: ex oriente e.V., 2012.

Shodoev, Nikolai. 2012. Spiritual Wisdom from the Altai Mountains. Alresford, Hants., UK.: John Hunt Publishing.

“Speak with a forked tongue.” 2018. Grammarist website.

Tedlock, Dennis, trans. 1996. Popol Vuh: The Definitive Edition of the Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of Gods and Kings. New York: Touchstone. Translation originally published in 1985 under the title Popol Vuh: The Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life by Simon & Schuster in New York.

Treffert, Darold A. 2010. Islands of Genius: The Bountiful Mind of the Autistic, Acquired, and Sudden Savant. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Uyanik, Muvaffak. 1974. Petroglyphs of South-Eastern Anatolia. Graz, Austria: Akademishe Druck-u. Verlagsanstalt.

“World’s Oldest Needle Found in Siberian Cave that Stitches Together Human History.” 2016. Siberian Times website, August 23, 2016.

Zwyns, Nicolas, et al. 2019. “The northern Route for Human dispersal in central and northeast Asia: new evidence from the site of Tolbor-16, Mongolia.” Science Reports 9:11759, 1–10.

The author would like to thank Debbie Cartwright, Khanna Omarkhali, Ismail Khan, Nick Davies, Sabahattin Alkan, Hugh Newman, JJ Ainsworth and Richard Ward for their thoughts and comments on this article.

1 Private researcher, email [email protected]

Key words: Karahan Tepe, Göbekli Tepe, Taş Tepeler, Pre-Pottery Neolithic, Pillar 43, Milky Way, Galactic Bulge, Scorpius, Cygnus, cosmogony, cosmology, Paleolithic, Denisova Cave, Tolobor-16, anatomical modern humans, Denisovans, DNA, autism.

Hi, everyone. Andrew Collins here. Hope you enjoy this great introduction to Karahan Tepe and also my book of the same name. It is has been a project 20 years in the making following my first visit to the site back in 2004. Since then I have explored the site on countless occasions looking everywhere for clues regarding what was going on there as much as 11,000 years. The fruits of that research are published this month. I thanks Graham Hancock for hosting me as author of the month. Any queries or questions do let me know. I shall be following the progress of this debate as the month goes on

Have ordered my copy and can’t wait to start it! I have been looking forward to this book for a few months now and have watched the talks you had discussing it and some other Karahan Tepe details. Congratulations on the successful launch of another book and all I can say is, keep ’em coming 🙂 Much love from Canada

Kazem Shah

Mr. Collins continues with his interesting and thought-provoking research. In reference to the fox and serpent carving symbolism Mr. Collins notes, I would suggest an article I wrote for Ancient Origins approximately two years ago along with a follow up article on the subject that was published. Donald B Carroll Gobekli Tepe The Serpent and the fox R4 | Donald Carroll – Academia.edu

(99+)

Gōbekli Tepe: The Symbolism of the Serpent and the Fox-Revisited | Don C – Academia.edu

Non parlo né leggo in inglese, sono italiana ed amo l’archeologia. Sono stata a Gobleki Tepe e a Karan tepe la scorsa settimana, e le ho trovate così misteriose ed entusiasmanti, mi sono emozionata nel camminare tra le rovine pensando ad un tempo così remoto.Appena uscirà il libro lo leggerò e spero sia presto.

Anunnaki was warmongers despite of their father Anu, who warned his sons and all his family of wrong enemistic behavior. Many “wars of gods” occured as a result of strong affinity of Anunnaki to personal wealth and power (big ego) and no human feeling. There were false gods of long time lasting epoche. They belonged to originally extraterrestritan dark beings

Hi Andrew,

I find the connection you make between the world-encircling serpent and the Garden of Eden captivating. If you are interested in exploring another perspective on this topic, I recently published a paper that you might find interesting.

https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=136407

Thanks and good luck with the book.

Best Regards

Konstantin

Mans Origins South America & Migration To North America

Forum: Mysteries coffee2ful 14-Nov-24 16:00