It is with pleasure that we welcome our Author of the Month for February, David Anderson, and his unique view of one of the oldest jade carving cultures in human history.

David combines appreciation for art of the ancients with modern science, and contributes to the swelling evidential trail of the cometary Younger Dryas impact hypothesis.

In this book, I consider three of the principal hard stone minerals that have had a central role in Chinese culture. These are:

- Nephrite jade, a double chain silicate, with the negative charges balanced by Ca++, and Mg++ or Fe++, which was formed at high temperatures and pressures:

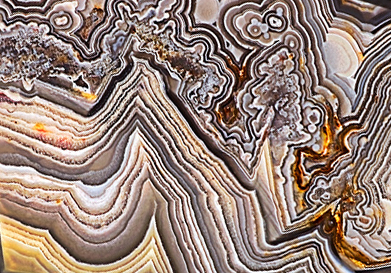

- Agate, a mineral formed from solution inside volcanic cavities, containing SiO2 bands alternating between quartz and a more reactive spiral form of silica called moganite:

- Shui jing, a natural glass, which is almost pure SiO2 with no additives or network modifiers, and so has a melting temperature in excess of 1,600 C (to add confusion, Chinese carvers use the same word for quartz (crystalline SiO2)):

All three minerals vary in colour in their own unique ways, depending on other included ions, minerals and contaminants. And they all have to be carved by grinding, because of their toughness and/or the propensity to shatter.

How did I discover Hongshan Jade?

In 1991, I moved from a secure medical life in Manchester, UK to Hong Kong, to become Professor of Medicine at the Chinese University, which was followed by a move into private medical practice three years later. Although interested in East Asian art and ceramics, I had never liked jade, until the year 2,000, when I bought my first Hongshan nephrite carving from a dealer in Cat Street. As a good customer, he let me have it at half price, for US$200. It remains one of my favourite pieces, depicting as it does a baby’s birth, Athena-style, through the head (Fig1). I see it as the god of safe delivery. Over the next ten years, I built a collection of nearly 2,000 Hongshan carvings, of which 350 or so are illustrated in the book.

Collecting Hongshan jade, especially small pendants, became extremely addictive. A friend directed me to Ebay, which in turn led me to a collector in Australia, and to the (now extinct) Chicochai Jade discussion forum. Ebay led me to other dealers in Hong Kong, especially one whose source was family members in China, who were buying from farmers and middle men in Inner Mongolia. For a long time, I collected with a medical friend, who therefore has almost as big a collection as I do. He, in turn, found another reliable dealer, Mr Wong in the Hong Kong jade market, who had a few genuine pieces on display (and many more in a box), among all the reproductions.

I soon found that established collectors of Hongshan jade were collecting pieces that looked to me modern, but were approved by ‘experts’. I argue strongly for the importance of internal evidence rather than external opinion; the conflict follows in part from the diametrically different and opposed business models of the tomb robber and the modern carver. The distinction is usually easy for archaic nephrite jade, since it is highly reactive and subject to weathering over time and under damp conditions. I devote one chapter of the book to authentication of archaic nephrite jade carvings, and what I found using a simple binocular microscope. It is probable that the iconography was largely developed in the jade medium, and then applied to agate and shui jing with new technology and especially the discovery of harder grinding materials, notably microdiamond ‘magic’ sand.

Hongshan iconography is rich and extremely diverse. At the outset, we need to look now at some of the many characteristic Hongshan icons, around which enormous artistic license seems to be present. These include the following; the Pig dragon (zhulong) (fig 2); the C dragon (fig 3); the Hawk (fig 4); the Cow God (fig 5); and erotica (fig 6).

Figure 2. Jade pig dragons (zhulong) – note the left one with weathering is defined by experts as fake! ©David Anderson.

Figure 4. Clasical agate Hongshan hawk pendant; weathering typical of burial in high fluorine soil ©David Anderson.

Figure 5. Jade cow god pendant; mcroscopy (R) shows 2 types of manganese-containing crystals ©David Anderson.

Visits to Liaoning and Inner Mongolia

In 2004, I made my first visit to the main officially excavated Hongshan burial site, Niuheliang, with Professor Guo Da Shun, principal and revered Hongshan archeologist. Niuheliang’s ‘burial mound 13’ was a particularly impressive virgin burial mound (in an otherwise extensively ravaged site), so I offered to raise Hong Kong money for an official excavation. My offer, however, was finally turned down, and to my distress on returning four years later, I found that that the mound was being secretly raided right under the noses of the paid guards! With such apparent official disinterest, collectors who study and catalogue such objects are, I fear, the main conservers of this extraordinarily rich and diverse archaic culture.

Figure 7. Unweathered Hongshan agate pendants with same ‘bar code’, so from same nodule ©David Anderson.

Hongshan carvings in agate and China’s unique Shui Jing natural glass

Around 2005, many agate pieces with the same iconography began flooding the market, via Beijing dealers on Ebay (figs 3 and 7). I have been greatly helped in my studies by colleagues in the Nanovision Centre at Queen Mary University of London, and at Johnson Matthey Ltd. For example, we found that agate carvings showing the kind of banded weathering seen on the hawk in Figure 3 were high in surface fluorine, presumably derived from soil at the burial site. Hydrofluoric acid is particularly corrosive for silica and especially moganite. Agate, unlike nephrite jade, does not react with water alone, so many genuine pieces will appear unchanged after prolonged burial.

Figure 8. Humble zhulong in shui jing: suspension hole contained microdiamonds used for carving ©David Anderson.

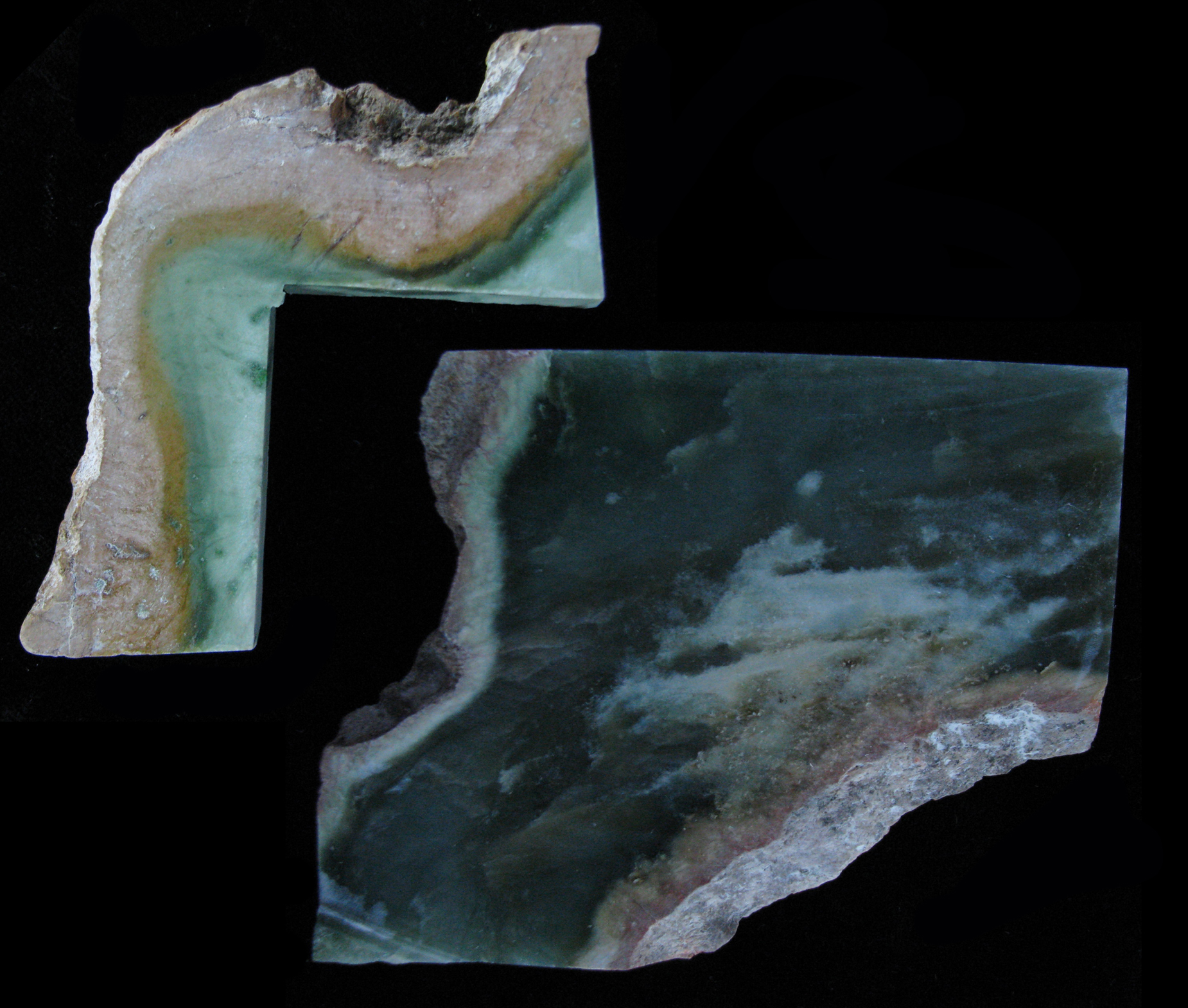

I found my first piece of Hongshan shui jing, a simple zhulong (fig 8) in the Hong Kong jade market in 2007, and when I got home and put it under the microscope I found in the suspension hole hundreds of tiny glistening microspheres (later proved by EDX and Raman spectroscopy to be microdiamonds). I posted pictures of the zhulong on the discussion forum, and simply created further skeptics! However, they pointed me to Ebay, where such carvings were openly flooding out through dealers buying at Shi Li He market in Beijing, at very low prices. I started collecting and studying them. The iconography was typical (figs 3, 8 & 9), and the glass varied greatly in colour and in quality. The most extraordinary pieces are the tubes, some of which are exquisitely carved around natural holes (fig10).

Figure 9. Classical C dragon in poor quality glass with inclusions from ejecta & encased soil melt ©David Anderson.

The importance to this discussion of shui jing is that as with libyan desert glass, it can only have been formed by a massive meteorite strike, probably impacting on a desert high in silica sand. But where was and is the glass mined, and where is the impact site?

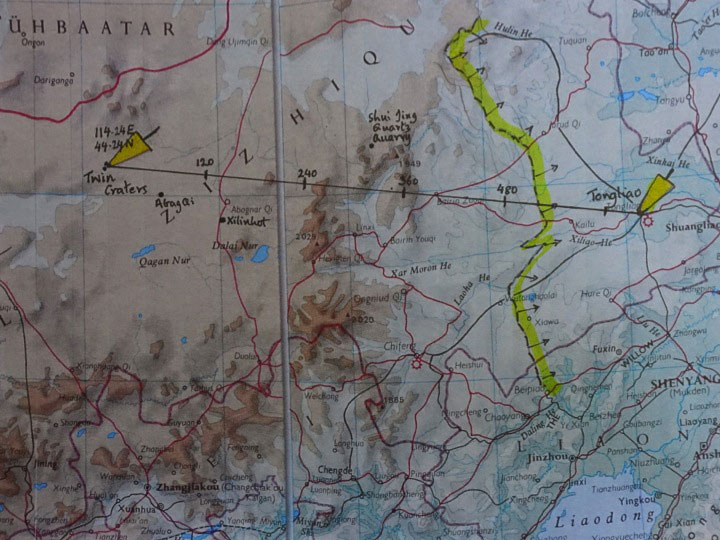

Figure 11. North China map with twin craters, Tong Liao, and possible ejection path – see Youtube lecture part 1, part 2, part 3.

Frustration in the quest to locate the impact site and the glass mines.

I discuss evidence in the book, and in my recent lecture (part 1, part 2, part 3) proving that this unique glass was formed by a large meteorite impact whereby pure gaseous and liquid SiO2 was ejected at a low angle, picked up other ejecta, and formed spheres of up to 1 meter in diameter. Strong circumstantial evidence points to the location of the mine or quarry in or around Tong Liao prefecture (fig11). I have no doubt that it was treated with great respect by the Hongshan carvers, who used impact diamonds as the ‘magic sand’ necessary to carve it by grinding.

Figure 13. ‘Shui jing’ also describes quartz; this faked pseudo-crystal had non-parallel faces ©David Anderson.

Finding the robbed tombs is likely to be impossible. But there is overwhelming evidence that the glass itself is still being mined/quarried privately, and simply wasted on frivolous executive toys (figs12-14), or crushed and added as a bulking agent to porcelain (fig15). I have tried, on four personal expeditions from 2010-15 to Inner Mongolia, to locate both the impact site and the glass mines. The location of the latter must point to the former (which may then be dated by geologists). Does it support the hypothesis that the twin craters I found on Google Earth at 114.14E, 44.14N are in fact impact craters, with secondary volcanism post-impact that has confused the experts? (fig 16) When and where did this impact happen, and how can those in power in China be convinced of its importance, if only for geo-tourism? These are important questions, which need urgently to be both asked and answered.

Figure 15. Two shui jing shards for crushing as an additive to porcelain in Porcelain City ©David Anderson.

Figure 16. Google Earth images of twin craters Chule Wule and Esige Wule (right, in winter). Are these calderas, or impact craters with secondary reactivated volcanism? ©David Anderson.

Conclusion

This journey began with Hongshan carvings in jade, and moved on to agate and shui jing glass. The latter (with attendant official denial) points to a meteorite impact in a related area. Ultimately, the glass was carved by specialists who were already expert in working with jade. They must have used sophisticated machinery, impact diamonds, and techniques on a small scale as remarkable as those needed for the creation of megalithic monuments. So where (and indeed when) did Hongshan carvers start? Is this culture, too, even older than is currently acknowledged? Did it even witness that fateful impact?

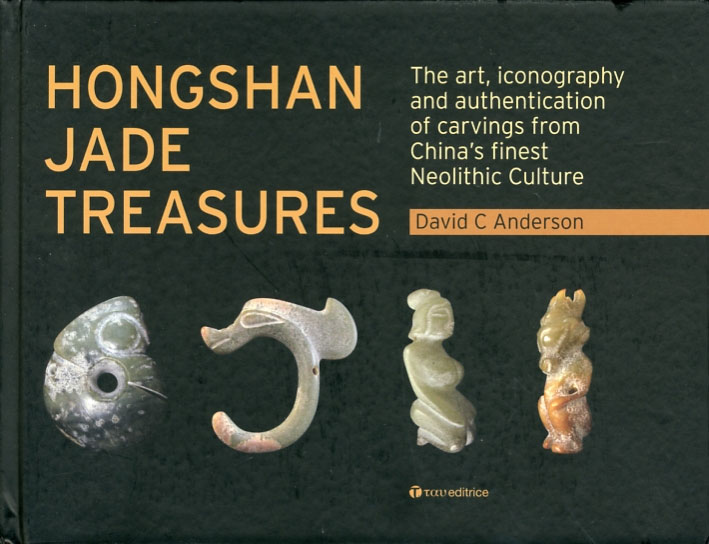

I am sure that the answers to these and other questions in part lie in a deeper study of the objects themselves. My book Hongshan Jade Treasures documents yet another example of the damage done to humankind’s collective past by wilful destruction and official academic neglect. It is high time that China’s collectors, officials and museums, as well as UNESCO, woke up to and became curators of this extraordinary historical, cultural, and geological human legacy.

About the author

Dr David C Anderson, born in 1940, is a retired physician who held a personal chair in Endocrinology in Manchester, before moving to Hong Kong as Professor of Medicine at the Chinese University in 1991. He then moved into private practice, before retiring in 2008. He now lives in Umbria, Italy. As well as numerous medical research publications, he authored a 60 film medical teaching film series ‘MediVision’. He has long been interested in oriental art, and in 2000 started to collect and study carvings from the Hongshan culture. His book is mainly based on his collection of nearly two thousand such carvings in nephrite jade, agate and a unique natural silica glass called shui jing. The latter, which is undoubtedly still being quarried, was formed by a unique meteorite impact probably in Inner Mongolia. He has recently also co-authored a book on injustice, entitled Three False Convictions, Many Lessons – the Psychopathology of Unjust Prosecutions (Waterside Press, 2016).

Consider also powerful electrical discarge hypotesis as origin, not only impact. See https://www.thunderbolts.info/wp/. Among others this video summarises how electrical hypotesis better explain featurs of craters https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BnIcP4v_T8Y

I really enjoyed reading your article.

Dr. Anderson,

Always a pleasure to read your writings on the Hongshan. Is it possible there are still other large scale deposits of shui jin glass elsewhere in the vicinity too waiting to be discovered? Also, Is carving of shui jin unique to the Hongshan or are there other instances of Neolithic cultures or in the dynastic period where carvings of shui jin are found?

Also, I would recommend watching Dr. Anderson’s lectures on youtube to anyone interested in learning more about Hongshan Art if you have not already. Very well presented and very informative!

This is a link to his channel.

https://www.youtube.com/user/drdavidanderson

Thanks ambrogio, Tracey and Andrew. I am mainly commenting on the AoM part of this site. But ambrogio, I suggest in my lecture that electrical storms would follow such an impact, and postulate that lightning discharges on a glass deposit may be responsible for the tubes, because the central holes have to have been natural. I shall post a thread on the tubes shortly. Once holes arose they would have had the technology to ream them out. I also agree that there may have been quite a large strewn field, with much glass ejected in splats rather than spheres. And the tubes are composed of almost pure silica glass

I have a copy of the book and can really recommend it. Extremely interesting and well illustrated. A lot of scientific research and exploration have gone into the preparation of this book. Enjoyed your article as well.

Dear Dr. Anderson,

Your research has proven to be most helpful to me in my own study on Liuli Glass (China’s Lost National Treasure). Shui jing is actually used to refer to clear quartz crystal, while Liuli was used in ancient China to refer to a natural glass. I would like to share my research with you, if you are interested. It may give insight into where Liuli glass was mined and understand how the meaning of Liuli transitioned over time.

I would like to know where I can purchase this book in Australia as I am a collector of archaic jade