It’s our pleasure to welcome Andrew Gallimore, author of Death by Astonishment: Confronting the Mystery of the World’s Strangest Drug. Andrew’s book presents the first detailed account of the discovery of DMT, as well as science’s ongoing struggle to explain how such a simple and common plant molecule can have such astonishing effects on the human mind. His book explores the contributions fascinating characters from the scientific and literary worlds have made to the DMT narrative, including the legendary ethnobotanist Dr. Richard Schultes, the renegade beat writer and drug aficionado William S. Burroughs, and the philosopher and raconteur Terence McKenna. In his article, Andrew delves into the profound realm of mystery and astonishment found in the DMT state, introducing the reader to the story of DMT, which begins in the Amazonian rainforests and ends somewhere beyond the stars, forcing us to reconsider our most basic assumptions about the nature of reality and our place within it.

Interact with Andrew on our AoM Forum here.

Although much of my adolescence was spent cultivating exotic and supposedly psychoactive plants and herbs under a small grow lamp hung awkwardly beneath a desk in my bedroom, I was, by modern standards at least, relatively late to the psychedelic party: I didn’t have what I would consider to be a “proper” psychedelic experience until my early twenties. It was barely three years since Terence McKenna, who had already become something of an idol of mine, had made his final transition into the Great Mystery and I, then a young PhD student with a deep interest in psychedelics but with very little practical experience, hopped on the train from Cambridge down to the beautiful Roman city of Bath in the south west of the UK to attend my very first psychedelic symposium1. Most of the three-day event, which seemed to be an eclectic mix of psychedelics, philosophy, and astrology, is now something of a blur, but it was the final evening, once the formalities had been concluded, that holds permanent residence in my psyche.

While most of the speakers and other attendees had drifted off elsewhere, perhaps a dozen or so of us wandered to a park by a river for a final, less formal, summer gathering. Among that motley crew was MAPS founder Rick Doblin, who ambled into the assembled circle lugging what appeared to be a large Tupperware tub and sat down on the grass just a few feet away from me. And as the sun dipped below the horizon, he finally cracked open this mystery box, which was neatly packed to the brim with the finest examples of fresh Psilocybe cubensis I’d ever seen (This was during a less authoritarian era when fresh — “unprepared” — magic mushrooms were perfectly legal under UK law). He began to pass the plump phallic fungi around, and a particularly juicy pair found their way into my hands. Although I hadn’t planned on consuming anything beyond the bottle of cheap red wine I’d bought from a nearby off-licence, this seemed like as good a time and place as any, so I slowly began to nibble them down.

From my prior four years as an undergraduate student, I was reasonably familiar with the powerful rushing sensation as a drug — mainly one particularly prominent member of the phenethylamine family — got to work on my central nervous system. But this felt different: It was as if every cell in my body had become electrified, and this energy then began to course through my entire being, continuing to intensify until I could sit still no more. So, I rose unsteadily to my feet and soon found myself wandering among a small clutch of trees minding their own business at the edge of the park. And then I noticed something, both entirely new and yet somehow familiar. I can only describe it as like stepping into a fairytale. What would, in sober waking life, have appeared as a perfectly unremarkable collection of perfectly unremarkable trees became, instead, an enchanted wood. Yes, if I was to describe my first mushroom experience in a single word, that would be it: Enchantment. What struck me later about this experience was that “enchantment” was a word I thought I understood, but was, in truth, something I had never really experienced (at least as far as I could recall).

At the time I wasn’t particularly interested in the deeper meaning or philosophical implications of psychedelics: questions about the ontological status of alternate realities, non-human discarnate intelligences, machine elves and the like that would come to dominate my work in the decades that followed. Psychedelics simply seemed to provide a direct path back to that enchanted wood, back to a magical enchanted world. While I had been fascinated by the chemistry and pharmacology of psychoactive drugs for several years prior, it was that first bemushrooming in Bath that cemented my desire to try to understand how these drugs interfaced with the brain to achieve their effects on consciousness. But it was another psychedelic experience, just a few years later, with a different but closely related naturally-occurring molecule that, rather than ushering me gently into the forest of the enchanted, would drag me with violent force into direct confrontation with another type of emotion that I thought I understood and, yet, as it turned out, was also entirely new.

I first heard about DMT — N,N,-dimethyltryptamine — several years before my mushroom munching with Doblin, from Terence McKenna (naturally), but this was long before powdered Mimosa hostilis root bark was a thing in psychedelic circles and, unless you had access to a particularly well-stocked dealer or happened to be part of a well-connected psychedelic in-group (I wasn’t), DMT was quite hard to find. But when the opportunity to take DMT did finally arrive a few years later, having primed my brain with all the stories of elves and imps; jesters and jokers; reptilian and insectoid aliens; the mischievous, magical, and menacing creatures that would surely greet me on the other side of the veil, I knew exactly what I was expecting to see. But it was nothing like I was expecting. It was nothing like anything I could possibly have expected or imagined. If I was to describe the experience in a single word, it wouldn’t be enchantment, but pure, bright white, absolute astonishment. Terence McKenna was right when he said that astonishment is not merely rare but perhaps the rarest of emotions. I’m talking here about true astonishment and not the watered-down version that acts as a synonym for the merely somewhat shocked or surprised. I dare say that few ever experience true astonishment and yet DMT delivers it on tap — anyone who’s ever gotten a full breakthrough hit of DMT knows that his famous warning of the risk of “death by astonishment” (which was obviously the only possible acceptable title for my new book about DMT) doesn’t feel like hyperbole.

As the molecule slipped into my brain, I wasn’t greeted by an enchanted version of the normal waking world, but another world entirely. Of course, I had no idea where or what this world was but, in those moments as the molecule seized and overwhelmed me, although McKenna’s elves were nowhere to be seen and the insectoids remained out of sight, it was undeniably apparent to me that I had somehow found myself in an alternate reality constructed by the hand of an immense and timeless alien intelligence. And, if I’m honest, it horrified me. A world not merely strange but transcending the imagination in its utter and absolute alienness, irresistible in its construction and undeniable in its presence.

Of course, I was far from the first to be left reeling and aghast by DMT, but for the first time in my life, I was presented with what appeared to be a true mystery, with something that didn’t seem possible. And, to me at least, this was big news. This was a substance of massive import that had the potential to completely transform our understanding of reality and of our place within it. Perhaps the most profoundly important world-shattering discovery we’ve ever stumbled upon as a species — something that ought to have been howled from the rooftops. And yet, as eloquently vocal as McKenna was in his repeated insistence that DMT is the strangest, most intense, beautiful, bizarre and inexplicable state of consciousness a human can experience “this side of the yawning grave”, the reporting of this news by the mainstream scientific community seemed decidedly muted.

In the wake of that first DMT trip, as I eagerly graduated from online trip reports to the academic journals, I wasn’t greeted by scientists throwing up their hands and declaring this to be the next great mystery to be tackled by humankind, uprooting all our cherished beliefs about the nature of reality. Instead, in the more mainstream academic journals at least, DMT was described in disappointingly mundane terms: a highly visual psychedelic comparable to psilocybin and LSD, albeit with a much faster onset and shorter duration of action. Was that it? I’m not sure what I was expecting, but – perhaps naively – I was expecting a little more than this. What about the hypertechnological cityscapes and alien civilisations? What about the machine elves jabbering in an indecipherable tongue and singing impossible objects into existence? Nothing. It didn’t make any sense. Science clearly hadn’t gotten the message or, if it had, had failed to understand its significance.

This somewhat lacklustre appraisal of DMT in scientific circles certainly isn’t new. In its pure form, DMT was unleashed upon the Western mind in 1956 by Hungarian physician Dr. Stephen Szára, who synthesised the molecule himself (he was also an organic chemist) and, in the spirit of the times, established its remarkable visionary properties by injecting it into his own bloodstream2. Psychologist David Luke and myself interviewed Dr. Szára just a few years prior to his passing, and we were keen to hear what he made of the strange non-human creatures that made an appearance in his very first studies of DMT in human subjects. But he had little to offer, admitting:

“When these experiences (such as God, strange creatures, other worldliness) appeared in our DMT studies, we did not philosophize about them, but as psychiatrists, we simply classified them as hallucinations.”3

For most psychiatrists working with DMT at the time (and indeed since) that attitude seemed to be standard: a hallucination is a hallucination is a hallucination. To me this was obviously not the case, but it seems most just weren’t particularly interested in the structure and content of an experience that seems so far beyond anything that might be connected to the human condition. As McKenna occasionally wondered aloud: What are we to do with an elf?

It wasn’t until Dr. Rick Strassman began studying DMT in the 1990s — the largest study of its kind ever conducted — that the phenomenology of DMT itself got the full science treatment. All sixty of his volunteers received pure DMT at several dose levels via intravenous injection and their trip reports carefully recorded in an extensive set of bedside notes that later formed the basis of his magnum opus, DMT — The Spirit Molecule4. But even after the publication of Strassman’s work and it having been made abundantly clear — to me at least — that DMT was doing something to human consciousness that was far from easy to explain, very few mainstream scientists seemed to take the DMT state seriously beyond noting it as a particularly intense short-acting psychedelic with the propensity to induce visions of non-human entities (as if that alone wasn’t remarkable).

Even now, three decades since Strassman’s study was concluded, it’s not difficult to find examples of scientists, most of whom I can only assume have never taken DMT, attempting to slot the DMT state into neatly demarcated phenomenological categories that make it seem as if the drug’s effects are easier to explain than they really are. Just a couple of years ago, I stumbled upon a Twitter (X, whatever) post by a fairly well-established cognitive neuropharmacologist whom I shan’t name and shame, but who works in the psychedelic field, where he referred to encounters with non-human/non-animal entities in the DMT state as “Illusory Social Events” (or simply “ISEs” for short — I think he hoped his coinage would catch on). I wasn’t sure whether to laugh or cry. If he really thinks the interactions with super-intelligent alien beings commonly described by DMT users are “social events”, I’d very much like to know the kinds of parties this guy frequents. To anyone who’s had an encounter with the kinds of entities frequently encountered in the DMT state, this “ISE” moniker just seems, well, silly.

Another neuroscientist, also working with psychedelics, put out one of those articles a year or so ago, which, as a rule, I avoid, but, in this case, I couldn’t help myself. You can recognise them by their title, which begins with the direct negation of that thing you believe but are wrong about, because they know better: “No, DMT Aliens Aren’t Real”, we’re reliably informed from the off5. Following the razor-sharp insight that “just because it feels real, doesn’t mean it is”, and after reminding us that anyone who doubts his assertion that DMT entities are mere “figments created by your brain” is “absolutely wrong”, Terence McKenna is then ushered into this laboratory of reason. I won’t go into the details – I’m sure you’ve heard them all before – but, yeah: McKenna, Machine Elves, The. Power. Of. Suggestion… you get the idea. (It is worth pointing out that diminutive elf-like creatures have been making an appearance in trip reports going back to Szára’s first study in the 1950s and in indigenous reports going back at least hundreds of years, if not millennia).

Finally, after a pointless detour into the Sigma-1 receptor and the entirely baseless pondering: “Can this Sigma-1 activation also be responsible for the entity-manifesting abilities of DMT?” (How? Why? What?), and a not-so-subtle insinuation that people who take DMT entities seriously can be compared to Flat Earthers, we get to the nitty-gritty of his explanation for the multitudinous Machine Elves and their ilk. Although this neuroscientist really really wanted to believe that the Machine Elves were more than just figments of the cortical imaginarium — “But hear me when I say I want the DMT elves to be real.” — alas, science already has it all worked out: The Machine Elves and the other denizens of the hyperdimensional hinterlands are simply “caused by depolarization of pyramidal cells that attenuate thalamo-cortical circuits and disrupt thalamic afferents that cause a perturbation in functional connectivity of cortical and subcortical regions.” Well, that certainly settles it. In his defence, he admits that this sounds like “scientific doublespeak nonsense.” And, indeed, it does sound like nonsense because it is nonsense. Or, at least (and slightly more diplomatically), it offers absolutely nothing in the way of an explanation for DMT entities while giving the impression that it does — but that you’re simply not smart enough to understand how and why. Indeed, the problem with these kinds of articles, especially when written by scientists, is that they give the strong impression… nay, they definitively inform their readers with a wagging finger that we scientists have it all wrapped up (or will very soon, we promise!) and that they needn’t worry their little heads about it; that the effects of DMT can be neatly dealt with and present no more of a problem for science to explain than the ebb and flow of the summer tides.

And this kind of self-congratulatory, self-assured sophistry masquerading as explanatory power isn’t limited to the hard but also finds its way into the softer side of the sciences (sorry psychologists). If you’ve been hanging around in psychedelic circles for long enough, you’ll likely have come across those that, while admitting that the DMT worlds and their occupants might represent something of a knotty issue for neuroscience, all falls into place and is revealed in scintillating clarity once the books of mid-20th century psychoanalyst Carl Jung are consulted. Yes, that’s right, the machine elves and their hyper-dimensional housemates are nothing more than archetypal imagery bubbling up from the collective unconscious. Now, to be clear, I’m not denying the existence of a collective unconscious, nor of the archetypes that make it their home, but I do deny — and explain why in Death by Astonishment — that they provide an explanation for the effects of DMT. Of course, it’s hardly surprising that Jung’s ideas are so attractive to those who assume that, if a collective unconscious stuffed with archetypes can explain a certain subset of psychological phenomena, then it must surely explain anything and everything we throw at it. If the machine elves, mantid aliens, and other denizens of the tryptamine netherworlds can be summarily dismissed as mere “archetypal imagery” or, as has now become de rigeur in certain psychedelic circles, “autonomous fragments of the psyche” — as if it were entirely obvious that the psyche should shatter into a million pieces like a toppled wine glass — then we can avoid having to confront the possibility that the reality transforming effects of DMT might represent something truly mysterious and difficult to explain or, heaven forfend, to actually attempt to explain them. Indeed, the collective unconscious is the gift that keeps on giving, a magician’s hat from which any and all otherwise inexplicable psychological or experiential phenomena can be extracted with an awkward flourish. Once the collective unconscious is invoked, no further explanation is required. And that’s that. Well, I’m sorry, but that is far from that. In fact, I’d go so far as to say that that isn’t that at all — or that either.

As you might already have intuited, I won’t deny a certain degree of frustration when the DMT state is dismissed in this way, whether being reduced to exotic dream imagery, hallucinations weighted by suggestion, or archetypal relics of our hominid past. Of course, it’s far easier to call the DMT state “comparable to the dream state” than to confront the fact that it is anything but and that we have no idea why. And it’s easier to refer to the thoroughly alien non-human/non-animal entity encounters as “archetypal symbols” or, even more ridiculously, “illusory social events” than to admit that their origin and nature remains almost a complete mystery. I guess I’m kind of bored and, frankly, tired of listening to the same old shit from people who claim to know better. Insectoid aliens? Oh, they’re archetypal imagery. Machine Elves? Meh, fragments of the psyche. 9-dimensional liquid light energy creatures emitting streams of 7-dimensional micro-universes from each of their 500 backsides? Oh, yeah, they’re caused by depolarization of pyramidal cells that attenuate thalamo-cortical circuits and disrupt thalamic afferents. As if that meant something. As if it was any kind of explanation. I have no problem with DMT remaining unexplained, as a true mystery. But first, it must be admitted as such. It must be confronted as a mystery, not as something to be explained away so casually. In Death by Astonishment, I recount the experience of a Korean man who contacted me after a terrifying encounter with powerful and malicious insectoid aliens during an ayahuasca session in Peru that left him truly traumatised, convinced they’d captured his soul. To him, the question of the reality of the creatures that mocked and tortured him was not an academic one—for him, it was a matter of immense personal significance. As far as he was concerned, his very soul depended on it. I also present two previously unpublished reports from Strassman’s 1990s study that were so utterly and horrifyingly alien that it plunged one of them into a state of hypotensive shock that almost killed him: “It was like hell because there was nothing human… I was being mined, devoured by such strange alien forces.”6 I very much doubt either of these volunteers would have much patience with talk of dream imagery, archetypal symbols, and other neo-Jungian psychobabble.

My purpose in writing Death by Astonishment was partly to introduce those who know little, if anything, of this remarkable molecule to both its history and to science’s continuing struggle to make sense of its astonishing world-switching effects, but also as an attempt to convince those more familiar with DMT that making sense of it is indeed a struggle; that there is something extremely challenging to explain about DMT and that it represents a true enigma. The basis for my argument has remained fairly consistent over the last decade or so: The world you experience, whether in normal waking life or during dreaming, is constructed by your brain as a model fashioned from patterns of neural information. The brain evolved to construct a single subjective world as a model of the environment. We can use this basic axiom to explain how and why the world appears to you as it does: stable, predictable, and familiar, whilst dynamic and responsive to the ever-changing flow of events and processes occurring out there in the external environment. We can also, without too much difficulty, explain the dream world as a selective simulation of the waking world: The brain draws on the stored concepts, object models, and experiences it has learned during waking life while interacting with the environment to construct a dream world while almost entirely disconnected from sensory inputs. We can also explain how, in the presence of psychedelics, the old familiar world begins to break down, becomes more fluid and unstable, less predictable and novel. We can even explain how and why certain types of imagery, drawn from personal memory and, yes, influenced by inherited archetypal patterns, as well as from spontaneous emergent patterns of cortical activity, tend to present themselves to a tripper. But when the normal waking world is not only obliterated but replaced in its entirety with one that bears no relationship to the world left behind; when the brain somehow begins constructing worlds it has no business constructing, worlds populated by hyper-intelligent non-human discarnate entities with no referent in the normal waking world; highly coherent, more real than real higher-dimensional worlds of crystalline clarity and impossible narrative and structural complexity that not only don’t exist in normal waking life, but could not exist… well, then we have a problem:

“In constructing the DMT worlds, it’s almost as if the brain is using a language it never learned to speak, building models it never learned to construct—and doing so flawlessly. The brain’s ability to fabricate these entirely nonhuman worlds in such exquisite and dynamic detail and complexity and with such effortless and lissome virtuosity is at least as confounding as a five-year-old British child waking up one morning and between mouthfuls of Frosted Mini-Wheats offering a confident but measured perspective on twentieth-century Sino-Russian relations in fluent Siberian Yupik.”7

Of course, one explanation for the regular appearance of certain types of highly advanced and intelligent entities in the DMT space is that we are indeed interacting with some kind of intelligence — or intelligences — external to the brain; that DMT gates access to some alternate source of sensory inputs that direct and modulate the bizarre alternate world experienced under its influence. But while such an idea is almost universally rejected without much consideration by my contemporaries in the scientific world, we might find that, if we are truly interested in understanding DMT, rather than simply explaining its effects away, we might be forced to reassess that assumption. Of course, it’s not as if the many indigenous peoples of South America and beyond haven’t been saying this for millennia. None of us, and certainly not me, can take credit for that idea. It’s perhaps partly a reaction to the self-assured attitudes of modern scientists in dismissing these convictions as the irrational magical beliefs of the savage and uncivilised, that I can’t help but speak in their defence. When shamanistic cultures claim to communicate with discarnate intelligent beings under the influence of DMT-based plant preparations, they really mean it — and they just might be onto something. I guess it’s difficult for the post-Enlightenment mind to accept that seemingly more primitive minds might have gotten to the truth of the matter long before us.

In Death by Astonishment, as well as discussing the work and ideas of those who have played central roles in the history of DMT, such as Stephen Szára, the McKenna brothers, Tim Leary, Bill Burroughs, among many others less well known, and analysing, testing and, ultimately, rejecting the more orthodox explanations for DMT’s effects, I also take pains to emphasise the foundational importance of the shamanistic peoples who have been working with DMT far longer than we have; cultures that developed what can, in all fairness, only be described not merely as DMT-containing plant-based drugs but true pharmacological technologies — what Brazilian anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro described as “visual prostheses”8— to render the hidden visible and to establish and maintain relationships with these beings as we establish and maintain relationships with each other. And if we too begin to take seriously the idea that DMT grants us access to some kind of true discarnate intelligence (and I argue at length in Death by Astonishment why we ought to), then we begin to see DMT, not as just another psychedelic opening up a path back to an enchantment lost, but as “a technology that we are now charged with carrying from its forest roots, carefully, respectfully, optimistically, into a future that seems to approach with ever-increasing speed and yet which, for the most part, likely remains beyond our imagination.”9

Earlier this morning, I was speaking with Dennis McKenna for his podcast, and our conversation turned to the frustration felt when attempting to make any kind of sense of the messages these immense intelligences often seem so eager to transmit in the DMT state. What could all these inordinately complex hyper-dimensional elfin machinations mean? Why can’t they just give it to us straight? Where are the equations for the Grand Unified Theory? Where are the blueprints for the time machine? In the end, we both converged on the same position: Perhaps we’re far from ready for the Big Message. Perhaps blueprints for intergalactic space-faring vehicles aren’t in our – or anyone else’s – best interests. Perhaps, to really understand DMT and the realms and intelligences to which it grants us access, we must first absorb and take to heart the simplest yet most important message, but one that seems uniquely difficult for us hominids, drenched in self-importance, to accept:

Get over yourself. You don’t know shit.

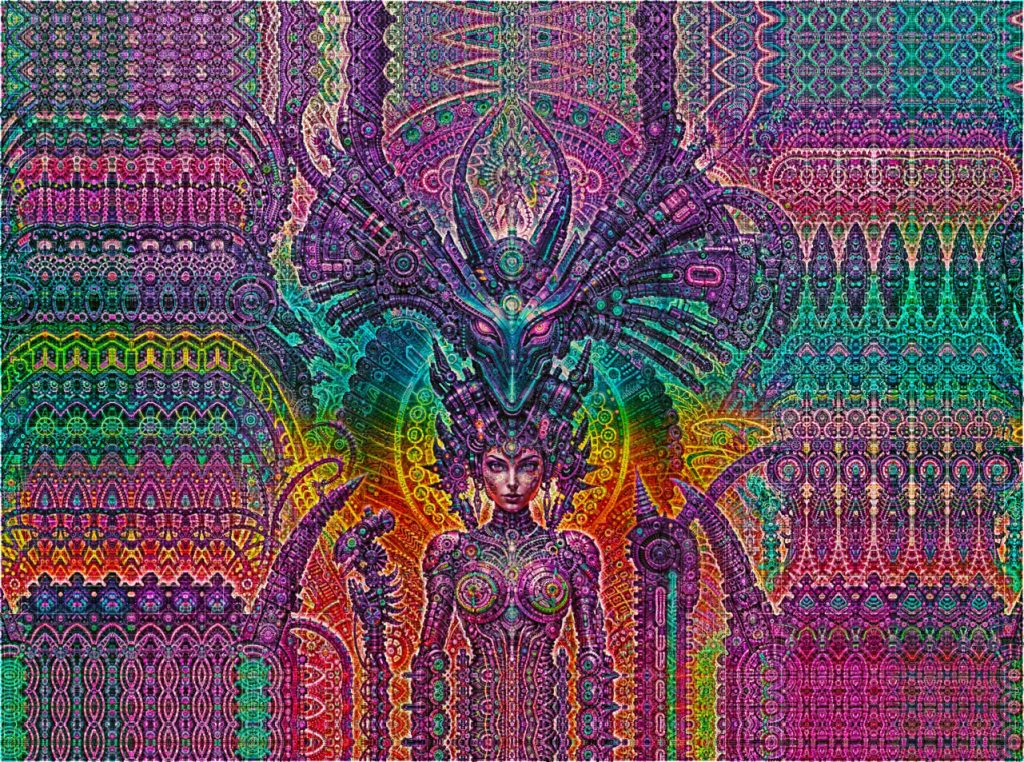

‘Depolarization of pyramidal cells that attenuate thalamo-cortical circuits and disrupt thalamic afferents.’ (aka ‘Strangeitude’ by Harry Pack)

Endorsements for Death by Astonishment:

“DMT is unique among all the psychedelics in that it affords access to an alternate reality that seems every bit as real as our ‘ordinary reality’ and yet is utterly alien. With the possible exception of Terence McKenna, Andrew Gallimore has been investigating this longer and more thoroughly than anyone else. I believe he may have cracked the code. His conclusions are astonishing. And to some they will be horrifying. This book is not to be missed.” – Dennis McKenna, PhD

“An exhilarating, yet rigorously grounded, account of DMT’s rapidly increasing influence on human consciousness. What if an unimaginably powerful psychedelic molecule, made in the human brain, could be harnessed to reliably provide contact with super intelligent beings from other dimensions of time and space? Gallimore’s project provides an essential understanding of this nascent field, and its implications for our species’ evolution.” – Rick Strassman MD, Adjunct Associate Professor of Psychiatry, University of New Mexico School of Medicine and author of DMT: The Spirit Molecule and My Altered States.

“Compulsively readable and impossible to put down, Death by Astonishment is a page-turning odyssey into the enigmatic history of the world’s strangest drug. Bringing together many of the most pivotal stories in psychedelic history, Gallimore not only connects the dots but also fills in the missing pieces, shedding new light on the mysteries of this extraordinary molecule.” – David Jay Brown, author of The Illustrated Field Guide to DMT Entities

“Peeling away the many layers of one of our greatest mysteries while leaving intact the enigma at its core, combining the erudition of a scholar and the precision of a scientist, Andrew Gallimore leads a fascinating inquiry into the heart of the unknown.” – Graham St John, author of Strange Attractor: The Hallucinatory Life of Terence McKenna (MIT Press, 2025)

References

1 Exploring Consciousness, 2004, https://maps.org/news/media/exploring-consciousness-conference/

2 Gallimore, A.R & Luke, D., 2013, DMT Research from 1956 to the Edge of Time, https://realitysandwich.com/dmt-research-from-1956-to-the-edge-of-time/

3 Ibid.

4 R. Strassman, 2001, DMT: The Spirit Molecule, Rochester: Park Street Press.

5 Tipado, Z. 2023, No, DMT Aliens Aren’t Real, Double Blind Mag, https://doubleblindmag.com/no-dmt-entities-arent-real/

6 Gallimore, A.R. 2025, Death by Astonishment, St. Martin’s Press, p.99

7 Gallimore, A.R. 2025, Death by Astonishment, St. Martin’s Press, p.150

8 de Castro, E. V. 2007, “The Crystal Forest: Notes on the Ontology of Amazonian Spirits,”

Inner Asia 9, no. 2.

9 Gallimore, A.R. 2025, Death by Astonishment, St. Martin’s Press, p.255