We warmly welcome George J. Haas, author of The Great Architects of Mars: Evidence for the Lost Civilisations on the Red Planet, as our featured author this month. George is the founder and premier investigator of the Mars research group known as The Cydonia Institute and is a member of the Society for Planetary SETI Research (SPSR). In his book, George investigates the possibility of a lost Martian civilisation and its contact with Earth by exploring a wide variety of geographical and structural anomalies on Mars’s surface that display a high degree of geometric and pictographic design. He also examines Mayan creation stories of a Star War and Sumerian myths of the Anunnaki, which he argues provide ancient evidence for the existence of a Martian culture. In his article here, George introduces the reader to the Parrot Geoglyph on Mars, examining the possibility that it has artificial origins.

Interact with George on our AoM Forum here.

THE EYE IN THE SKY

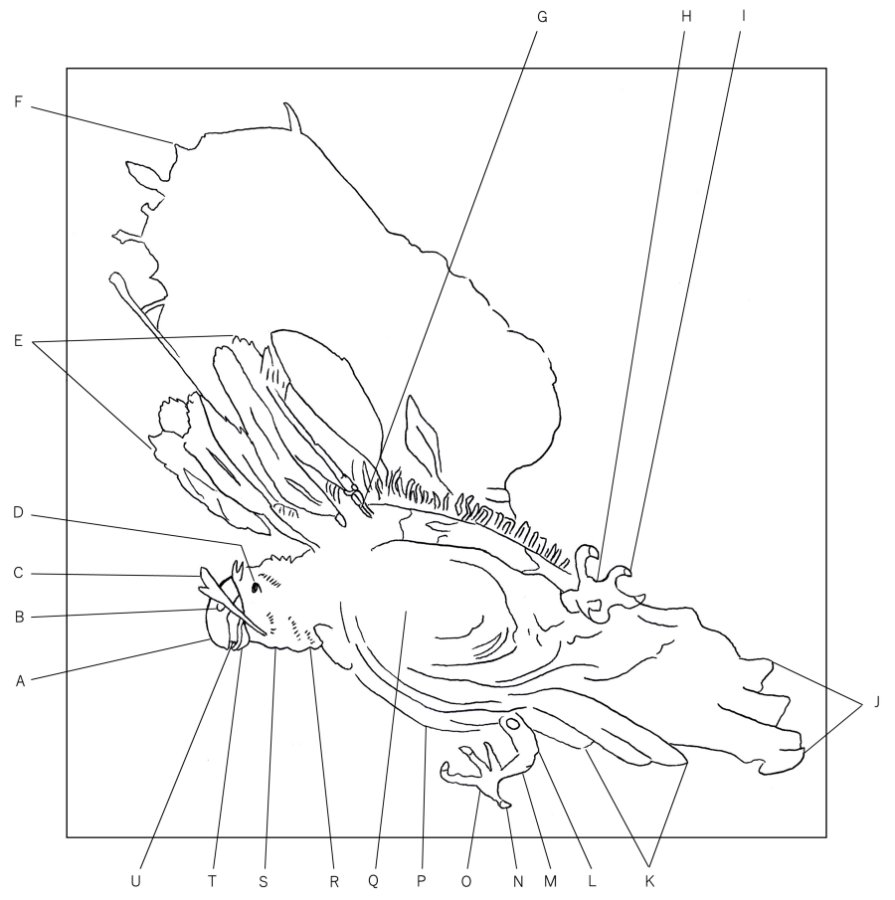

Humans have a long history of altering their environment by producing an extensive lexicon of geometric and pictographic earthworks. One of the first major discoveries of geoglyphic formations was the mysterious Nazca lines in Peru. These formations were left unseen for centuries as travelers unwittingly trampled over this sacred text. Amazing linear features such as this Condor (Figure 1) were first observed in the 1930s, when trans-Andean aviators began flying over the arid Nazca plateau. Pilots saw a vast assortment of lines that formed pictographic images of different types of birds and geometric patterns scattered across this ancient landscape.1

Archaeologists believe that many of these formations were created by some of our earliest cultures to establish memorials or monuments for worship and sacred ritual. Astronomers speculate that many of these mounds and linear formations may have been created to represent prominent constellations or to mark important planetary and solar alignments.

The creation of geoglyphic art works may also have been produced as territorial markers establishing tribal boundaries that could be seen from a high vantage point, such as a surrounding hill side or a distant mountain peak. Still, others believe they were constructed for no other reason than to communicate with the gods above, or be seen by the watchful eye of extraterrestrials.

Whatever rationale we use to consider or reject the idea of constructing such enormous geoglyphic formations here on earth, it is clear that mankind’s obsession with transforming its environment and producing pictographic or geometric monuments is a long-held human tradition. Perhaps these early builders contemplated the idea of constructing a visual “marker” that could be seen from space by a watchful eye in the sky and establish contact between two worlds.

This very question of finding a “marker” on another planet was addressed by a group of mainstream scientists in a 2014 book entitled Archaeology, Anthropology, and Interstellar Communication.2 The report, which was led by astrobiologist Douglas A. Vakoch, included NASA and SETI scientists along with archeologists and anthropologists, determined that the observation of rock art and sculptural carvings on a planetary surface should be considered as possible examples of extraterrestrial communication. The authors make the case that scientists may have difficulty identifying “manifestations of extraterrestrial intelligence” because they might “resemble a naturally occurring phenomenon.” This leaves the door open for the idea that an unknown, lost civilization could have left us a message on Earth, our moon or even on Mars that we are totally unequipped to understand or even recognize.3

THE PARROT GEOGLYPH

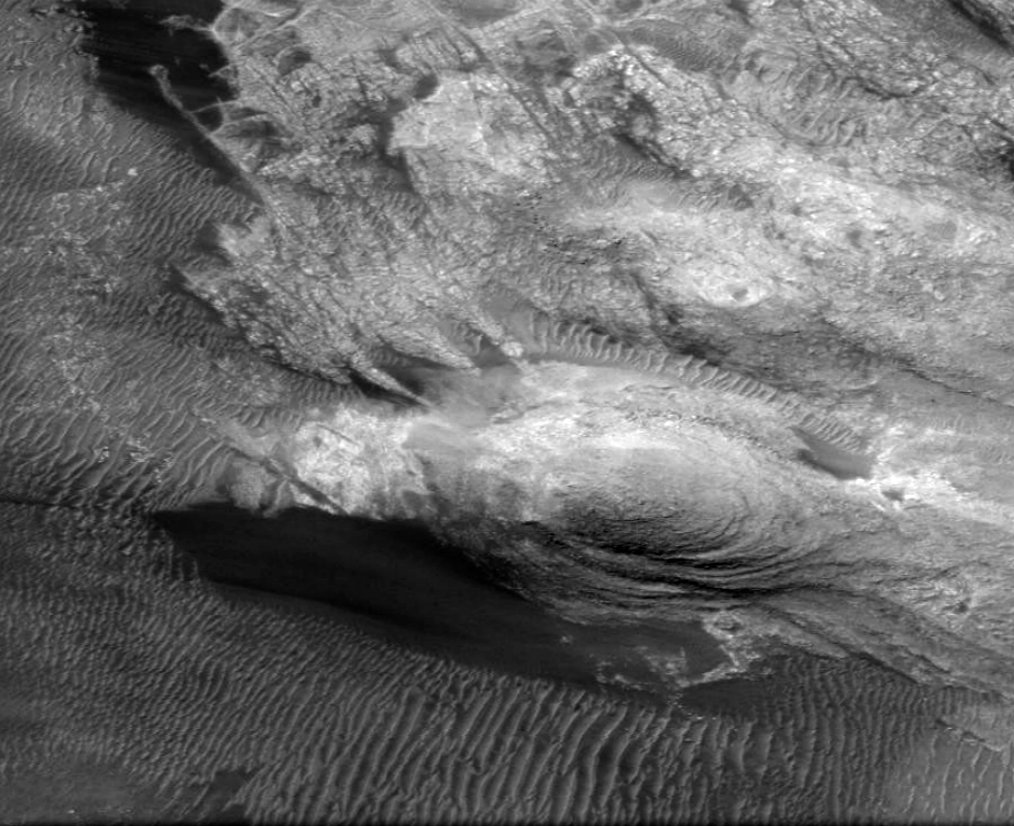

On March 7, 2002, independent researcher Wilmer Faust presented a Mars Global Surveyor image of an odd hillock formation that was located near a large-impact crater in the Argyre Basin area of Mars 4 to the members of The Cydonia Institute and The Anomaly Hunters discussion board.5 The image MGS image M1402185 (Figure 1) was taken in the spring, during the early evening with a resolution of 2.77 pixels per meter.6

Faust directed our attention to the compartmentalized structural features throughout the area’s topography as well as a formation of entirely different geometry that was very suggestive of a gigantic profile of a bird. He identified a mound-shaped body with a head that included an eye and beak. He noticed the body featured a leg and foot and an extended wing with sculpted feathers. Faust thought the shaping of the hillside wing was nearly a perfect rendering of the conformation of the feathers of a parrot’s wing. He also acknowledged that although the approximate shape of a parrot’s midsection might be due to chance erosional forces, the detail of its avian features was simply too realistic. He also made note of very fine feathers above the eye that accurately corresponds to the typical boundary of an avian eye patch.7

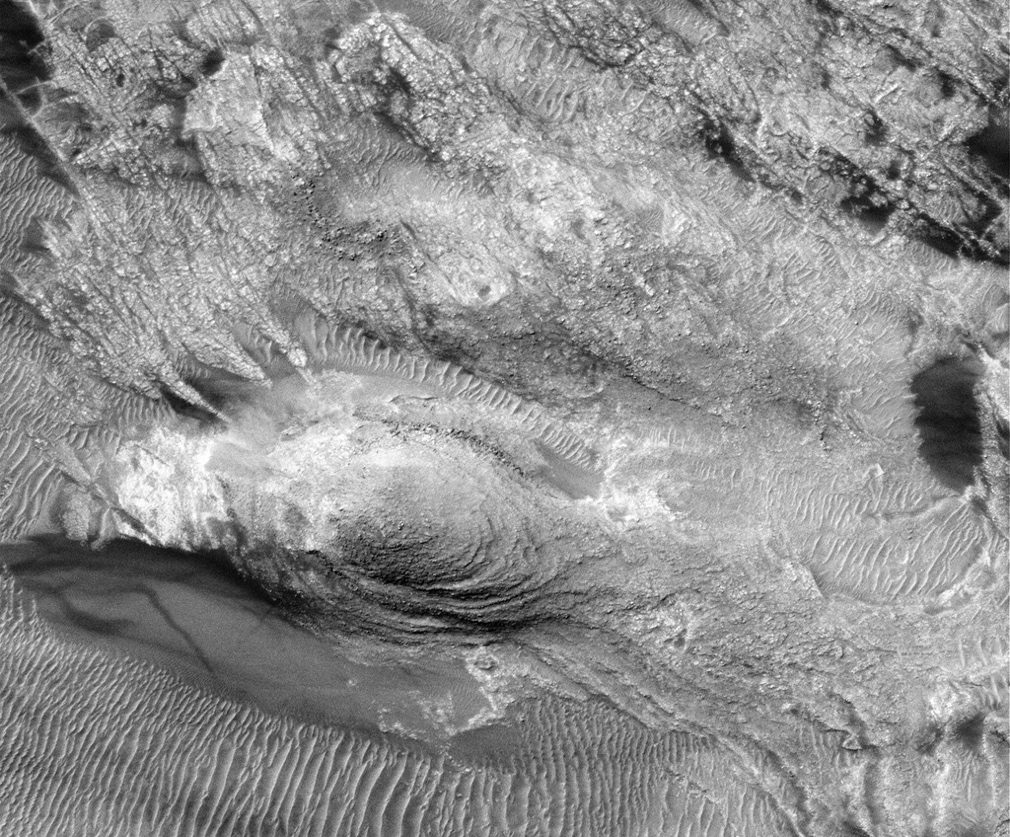

A SECOND MGS IMAGE

Another MGS image was released in the summer of 2009. This second image, S13-011480 (Figure 2), provides a clear and more complete image of the avian formation with an exceptional resolution of 1.43 meters per pixel.8 It shows the entire avian feature, including its head, body and the extent of the tail feature. It confirms the avian-shaped head, eye, beak, jaw and tongue. The oval-shaped body has a foot with claws and an upper wing form, and extending tail feathers.

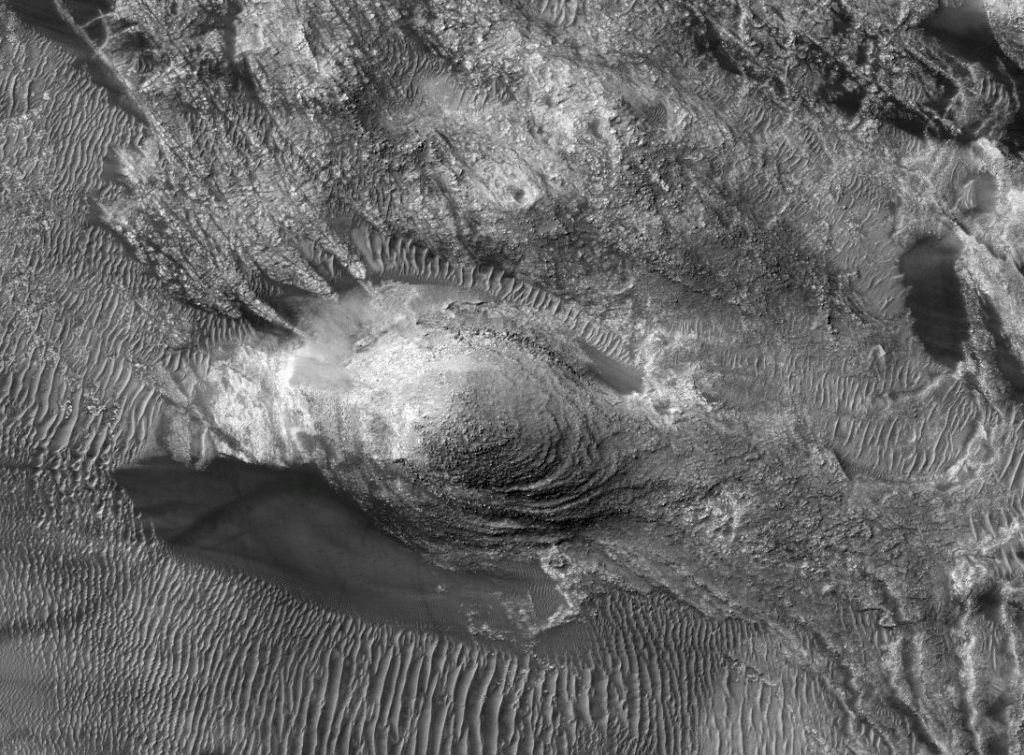

MRO HiRISE

On January 14, 2021, MRO HiRISE camera captured the highest resolution image ever taken of this Parrot geoglyph (Figure 3). The long-awaited image ESP_067824_1320 was acquired in the winter during the early afternoon with an exceptional resolution of 50.4 cm per pixel.9 This new image confirms all of the anatomical features observed in the earlier images with exquisite detail. The image also provides additional features, including a second foot with a set of splayed toes at the top of the body.

GEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS

A geologist Michael Dale and a geomorphologist William Saunders have examined both the MGS and MRO images of the Parrot Geoglyph 10 and found it to be composed of eight segments (Figure 4) The segments include an extended right wing (1), a beak (2), face (3), neck (4), the body (5), lower leg and foot (6) tail feathers (7) and second leg/foot (8). These segments are differentiated by height, color, patterning, contour, and lithology. The central mound (Labeled 5 in figure 4) that forms the body and tail is sedimentary in appearance. Since the height of the mound is roughly 175m 11 and sand dunes on Mars are typically only 10–25m in height, 12 an eolian depositional feature can likely be ruled out. The southwestern quadrant of the Argyre crater is suggested to have numerous glacial features, including eskers.13

Saunders and Dale contend that although the avian feature is in the northwest quadrant, the subglacial deposition in the form of a drumlin or esker that has undergone lithification would be the most likely candidates for the formation of the avian feature’s body. The layered or stratified appearance that gives the visual impression of bird feathers is similar to what could be formed through wind or water action, with the feature undergoing post-depositional erosion. The extended right wing (Labeled 1 in figure 4) is highly textured in appearance, with longitudinal and shorter perpendicular and slightly angular fractures. This is obviously a different lithology than the body, and its extensive fracturing is likely due to rapid cooling. What appears to be a block fault separates the beak from the face, forming the mouth (Labeled 2 in figure 4). Post-faulting depositional material is the most probable natural explanation for the tongue identified within the fault cavity. The composition of the beak (Labeled 2 in figure 4) could be composed of the same material as the body (Labeled 5 in figure 4) having been separated by the removal of material from the face area.14

The avian-shaped mound is truncated at the neck, leaving the portion of the structure between the neck and the beak structurally lower and forming the face (Labeled 3 in figure 4) by the exposure of an older underlying material, possibly from a lava flow. Interestingly, there is no wind-deposited material covering the face; however, wind action may be responsible for a darker material that appears to have been deposited up against the truncated body forming the hood or neck (labeled 4 in figure 4). The truncated and irregular edge at the juncture of the face and neck raises the question as to whether further erosion over the face occurred after this material was laid down.15

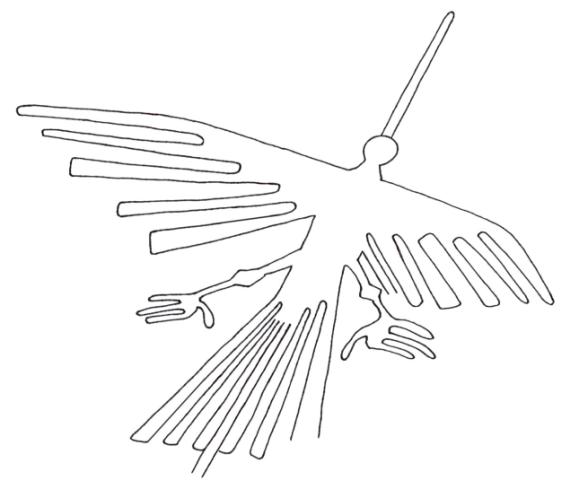

Figure 4 Eight Segments of the Parrot Geoglyph. Detailed crop of MRO HiRISE image ESP_067824_1320 (2021). 1) extended right wing, 2) beak, 3) face, 4) neck, 5) body 6) first leg/feet, 7) tail feathers and 8) second leg/feet. Notation and line annotations by the author.

Possibly the most interesting feature in the aspects of its structure and exposure is the right leg and foot (Labeled 6 in figure 4). The lighter color and structural level are similar to the face, indicating it likely consists of the same lithology. Interestingly, it remains exposed and has no windblown material obscuring it. The angular nature of the leg and toes would most conceivably be due to multidirectional faulting occurring prior to the deposition of the mound that forms the body. A possible left foot with splayed toes (Labeled 8 in figure 4) also has a light color, again indicating it likely consists of the same lithology as the face. The tail section flows towards the east 16 (Labeled 7 in figure 4) and conflates into the surface.

Their investigation concluded that it is apparent that the necessary geological and geomorphological processes to produce the avian-shaped feature took place in the Argyre Basin. However, the procession and precise distribution of the geological events needed to produce all the avian features in their present form and proportion are highly unlikely. One geological process would destroy the previous one, and so on. The formation appears to be the result of a composite structure of unrelated geological materials that have been transformed into a sculptural relief that express the prominent features of an avian creature when observed from above.

VETERINARIAN ANALYSIS

I contacted four veterinarians who agreed to provide an independent and impartial evaluation of the proposed avian formation observed within the Argyre Basin area of Mars. The four veterinarians include Dr. Amelia Cole in Virginia, Dr. Joseph Friedlander in New Jersey, Dr. Susan Orosz in Ohio and Dr. Erica Mollica in New York. They were each provided with access to JPEG images of the complete avian formation as obtained in the MGS and MRO images and an analytical drawing produced by the author highlighting its features. The group found the avian formation to be a sculpted formation containing 22 points of anatomical correctness.17 They also acknowledge that although the earliest fossil of a parrot-like bird dates to the late Cretaceous, about 70 million years ago,18 it is reasonable to suggest that of the 353 known species of parrots, the avian formation on Mars shares its anatomical template with the terrestrial King Parrot 19 (Figure 5).

The anatomical features observed by the veterinarians in MRO HiRISE image ESP_067824_1320 include an oval-shaped mound that conforms to the shape and size of a bird’s body resting on a folded right wing (Figure 6, point P). The avian formation is presented on its back with its abdomen exposed (Figure 6, point Q), while its left wing form (Figure 6, Point F) extends high above its body. On the left side of the mound-shaped body is a composite of structural elements that resemble a bird’s head (Figure 6, point S). The head includes the profiled view of an eye formation (Figure 6, point D) and a large parted beak (Figure 6, point A) with a lower jaw (Figure 6, point T). There is also evidence of a tongue (Figure 6, point U). The beak has a feather-like protuberance, referred to as a crest by Dr. Cole and Dr. Orzos, that extends from the beak and projects out from the head (Figure 6, point C). The modeling of the head is complex in its expression of texture and shading. The foreshortened orientation of the eye is remarkable in its proportion to the sightline expected within a profiled perspective. The plasticity of the beak appears hard and mantled, while the overall head and neck have a soft cauliflower look. Additional elements form an extended right leg (Figure 6, points L & M) and clawed foot with exceptional adherence to muscular definition at the knee joint (Figure 6, points N & O). The sculptural process of the leg appears to be fashioned in low relief and, in effect, has allowed sediment to cover portions of the detail. Attached to the body is an extended left wing along the back (Figure 6, point F) with exposed feather shafts (Figure 6, point G). Behind the right foot is a set of upper tail feathers (Figure 6, points K) that are again sculpted in low relief. The main tail extends from the body, ending with splayed tips (Figure 6, point J). A second foot with splayed toes is positioned along the northeastern side of the main body, at the rump 20 (Figure 6, points H & I).

Figure 6. Parrot geoglyph. Image source: MRO HiRISE image ESP_067824_1320 (2021). Analytical drawing by the author with notations by Dr. A. J. Cole. A) Beak. B) Cere. C) Crest. D) Eye. E) Primary flight feathers. F) Expanded wing. G) Feather shaft. H) Right foot and toes. I) Claw. J) Tail feathers. K) Upper tail feathers. L) Tibia. M) Tarsus joint. N) Claw. O) Left foot and toes. P) Folded right wing. Q) Abdomen. R) Neck. S) Head. T) Jaw. U) Tongue.

TERRESTRIAL COMPARISON

The idea of producing zoomorphic geoglyphs in the shape of a bird seems far-fetched, however, the Maya designed the city of Utatlán, which is located near present-day Santa Cruz del Quiché, in the form of an open-winged Parrot. Its avian form was not realized until a series of aerial reconnaissance studies were performed in the early 1970s by Dwight T. Wallace.21

After mapping the ruined city was complete, the architectural layout of its temples, monuments, and buildings began to take on the contours of a parrot with an upturned wing (Figure 7). The city of Utatlán was an important geoglyphic landmark founded by the early Quiché Maya and is even mentioned in the Popol Vuh.22 It was the fortress capital of the Quiché Highland state and was originally called Q’umarkaj, “Place of old reeds.”23 The only difference between the parrot-shaped complex in Santa Cruz and the one found on Mars is that the structural formations within Parrotopia reside only in the wing, while the structures that occupy the city of Utatlán reside within the entire bird.

Accepting the consensus that this simple mound and hillside rendering is an intentional work of art by the limits of aerial observations, it would be reasonable to suggest that the formal organization expressed within the Parrot geoglyph on Mars conflicts with the randomness of mere chance. There are no terrestrial geoglyphs that induce such a visual impression that approaches the fine modeling of the sculptural relief as seen within the Parrot Geoglyph at Argyre Basin.

This Parrot Geoglyph has been documented in three images in this analysis that were taken by two different NASA spacecraft, the Mars Global Surveyor and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. They were taken at three different times and seasons and over a twenty-year period. With respect to the modeling of its anatomical features, they are accurately depicted and remain clearly visible. All of its features appear to have permanence and are not the result of a transient phenomenon or an illusionary projection. Four veterinarians have found the formation to be exceptional in its physical appearance and anatomical completeness. While there are known geological mechanisms that are capable of creating the anatomical accuracies presented in this formation, the natural creation of a formation with an astounding 22 points of anatomical correctness seems to go well beyond the probability of chance. Therefore, I contend that the unique avian components of this Parrot Geoglyph are real and exhibit a level of consistency that is highly suspect of having artificial origins.

Since its original discovery by Wil Faust back in 2002, the Parrot Geoglyph has been the subject of two science papers, various books, and magazine articles. NASA lead scientist of the Mars Orbiter Camera, Michael C. Malin, featured it on the NASA/JPL website as the Image of the Day in August 2005 24 and it was also mentioned on the front page of the Wall Street Journal in 2012.25 The Parrot geoglyph has been showcased on the History Channel’s Ancient Aliens and The Proof is Out There and most importantly, as a “tip of the hat” to its discoverer, in 2020 imaging team at NASA titled the area in which it is located on Mars “Parrotopia.”

This set of images supports the visual impression of unique avian components that create a profiled view of a full-bodied parrot that is clearly recognizable. The formation exhibits a level of consistency of anatomical design that is highly suspect of having artificial origins. Therefore, I encourage NASA to pursue a ground survey of this area by future rover missions and recommend this site as a prime candidate for the study of potential archaeological artifacts on the surface of Mars.

References

1. Anthony F. Aveni, Solving the Mystery of the Nasca Lines, Archaeology, Volume 53 Number 3, May/June 2000, 26.

2. Douglas A. Vakoch, Archaeology, Anthropology, and Interstellar Communication, Nasa History, (Createspace Independent Pub, 2014).

3. Sarah Cascone, NASA Suggests Aliens May Be Behind Ancient Rock Art, Art World, May 24, 2014.

4. USGS, Astrogeology Science Center, Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature, Mars, Argyre Planitia, 2022.

5. Anomaly Hunters is a research group that was originally founded on Jan 20, 2002 by James S. Miller. The website had a Discussion Forum that was devoted specifically for co-operative studies of anomalous content in Mars image data. The website was shut down in 2009 and resurrected in the summer of 2021 as an online FaceBook group.

6. Mars Viewer, MOC, M1402185, S-facing slope on massif in W Argyre rim region, dated April 30, 2000.

7. Wil Faust, Anomaly Hunters, PARROTOPIA UPDATE No.1: Was the City a port?, January 10, 2003.

8. Mars Viewer, MOC S13-01480, Repeat layered material and rectilinear ridges in M14-02185, dated December 15, 2005.

9. Mars Viewer, MRO HiRISE, ESP_067824_1320. “Layered Knobs and Rectilinear Ridges in Nereidum Montes.” University of Arizona HiRISE website, January 14, 2021. Accessed March 23, 2023.

10. William R. Saunders et al, A Persistent Avian Formation on a South-Facing Slope, along the Northwest Rim of the Argyre Basin of Mars, Journal of Scientific Exploration, Volume 36 No. 2 Summer 2022.

11. William R. Saunders et al, Avian Formation on a South-Facing Slope Along the Northwest Rim of the Argyre Basin, Journal of Scientific Exploration, Volume 25, Issue 3, Fall, 2011.

12. R, Greeley, N, Lancaster, S, Lee & P. Thomas, Martian eolian processes, sediments, and features, Mars,(Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 1992), 730–766.

13. H. Hiesinger & J.W Head III, Topography and morphology of the Argyre Basin, Mars: Implications for its geologic and hydrologic history. Planetary and Space Science, 50, 2002, 939–981.

14. William R. Saunders et al, A Persistent Avian Formation on a South-Facing Slope, along the Northwest Rim of the Argyre Basin of Mars, Journal of Scientific Exploration, Volume 36 No. 2 Summer 2022.

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid.

17. B, Grzimek, Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia, second edition, Volume 9, Birds II (Thomson/Gale, 2003), 275.

18. William R. Saunders et al, A Persistent Avian Formation on a South-Facing Slope, along the Northwest Rim of the Argyre Basin of Mars, Journal of Scientific Exploration, Volume 36 No. 2 Summer 2022.

19. William R. Saunders et al, Avian Formation on a South-Facing Slope Along the Northwest Rim of the Argyre Basin, Journal of Scientific Exploration, Volume 25, Issue 3, Fall, 2011.

20. William R. Saunders et al, A Persistent Avian Formation on a South-Facing Slope, along the Northwest Rim of the Argyre Basin of Mars, Journal of Scientific Exploration, Volume 36 No. 2 Summer 2022.

21. Robert M. Carmack, The Quiché Mayas of Utatlán: The Evolution of a Highland Guatemala Kingdom (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1981), 214.

22. Thomas F. Babcock, Utatlán, The Constituted Community of the K’ iche’ Maya of Q’umarkaj (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2012), 5.

23. Joyce Kelly, An Archaeological Guide to North Central America: Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996), 200.

24. Malin Space Science Systems, Mars Global Surveyor, Mars Orbiter Camera, West Argyre, MGS MOC Release No. MOC2-1191, August 22, 2005.

25. Erica E. Phillips, Earthlings Look for Signs in New Photos of Mars, August 21, 2012, Wall Street Journal, Vol. CCLX, No. 43,1, A10.

Bibliography

Aveni, Anthony F. “Solving the Mystery of the Nasca Lines.” Archaeology 53, no. 3 (May/June 2000): 26–35.

Babcock, Thomas F., Utatlán, The Constituted Community of the K’ iche’ Maya of Q’umarkaj (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2012), 5.

Carmack, Robert M. The Quiché Mayas of Utatlán: The Evolution of a Highland Guatemala Kingdom (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1981), 214.

Cascone, Sarah. “NASA Suggests Aliens May Be Behind Ancient Rock Art” Art World website, May 24, 2014.

Faust, Wil, “Parrotopia Update No.1: Was the City a Port?” Parrotopia—Anomaly Hunters Roundtable Study website, (Wayback Machine). January 10, 2003.

Greeley, R, Lancaster, N, Lee, S & Thomas, P, Martian eolian processes, sediments, and features, Mars,(Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 1992), 730–766. Grzimek, B. Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia, second edition, Volume 9, Birds II (Thomson/Gale, 2003), 275.

Hiesinger, H., & Head, J. W., III, Topography and morphology of the Argyre Basin, Mars: Implications for its geologic and hydrologic history. Planetary and Space Science, 50, 2002, 939–981.

Kelly, Joyce, An Archaeological Guide to North Central America: Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996), 200.

Malin Space Science Systems, “West Argyre, MGS MOC Release No. M0C2-1191.” Mars Global Surveyor, Mars Orbiter Camera website, August 22, 2005.

Mars Viewer, MOC M1402185. “S-Facing Slope on Massif in W Argyre Rim Region.” Arizona State University Mars Space Flight Facility website (Mars Orbiter Camera), April 30, 2000.

Mars Viewer, MOC S13-01480. “Repeat Layered Material and Rectilinear Ridges in M14-02185.” Arizona State University Mars Space Flight Facility website (Mars Orbiter Camera), December 15, 2005.

Mars Viewer, MRO HiRISE, ESP_067824_1320. “Layered Knobs and Rectilinear Ridges in Nereidum Montes.” University of Arizona HiRISE website, January 14, 2021.

Phillips, Erica E., Earthlings Look for Signs in New Photos of Mars, August 21, 2012, Wall Street Journal, Vol. CCLX, No. 43,1, A10.

Saunders, William R. et al, A Persistent Avian Formation on a South-Facing Slope, along the Northwest Rim of the Argyre Basin of Mars, Journal of Scientific Exploration, Volume 36 No. 2 Summer 2022.

Saunders, William R. et al, Avian Formation on a South-Facing Slope Along the Northwest Rim of the Argyre Basin, Journal of Scientific Exploration, Volume 25, Issue 3, Fall, 2011.

USGS. “Argyre Planitia.” Astrogeology Science Center, Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature, Mars, 2022.

Vakoch, Douglas A. Archaeology, Anthropology, and Interstellar Communication. The NASA History Series. Createspace Independent Publishing Platform, 2014.

I want to believe, but, seriously, why would they create a monumental king parrot in an undignified, “roadkill” position?

For the life of me I can’t see the parrot in the photos, despite wanting to. It’s just not there for me. The lines in the overlay diagram seem to be arbitrarily placed, I cannot see a natural mark there in the clean photos. It is not apparent, or a parrot, to me. Not yet anyway. Please convince me because if king parrots are from Mars that would be perfect.

There is a great Aussie grindcore band with that name, they would be huge on Mars if true.

Hi Bob.

I’m sorry you are having trouble seeing the sculpted relief of the parrot formation. Some people have difficulty interpreting digital imagery. Features may seem inverted, like creator impressions that look like domes, etc. Try looking at it again, and stepping away from the screen.

My drawing follows the contours and details of the parrot precisely. It exhibits a set of 22 anatomical features that have been verified by over 5 veterinarians and three geologists.

In my book The Great Architects of Mars, I dedicate three chapters to the Parrot geoglyph.

Why a parrot?

Well, according to the Maya Creation story as recorded in the Popol Vuh they talk about a parrot called the Principle Bird Deity, a creature that is also known as Seven Macaw. The story says he stole the sun and while sitting at the top of the World Tree one of the Hero Twins shot him with his blow dart in the beak and he fell to earth. The Parrot Geoglyph on Mars is depicted as the Principle Bird Deity on the ground, dead, with a feathered dart in his beak.

I hope this was helpful.

Thanks for your interest

George J. Haas

Having co-authored the scientific paper referenced above and studied the parrot since it was presented by Wil Faust on my Anomaly Hunters Bulletin Boards back in 2001, I can only support the parrot and its many possible interpretations. Over the many years of study I personally have reached the conclusion that the area is actually a massive fish growing operation. Many have agreed that there are remnants of water storage, pipes and other parts that would support this idea. The entire compartmented area above the wing would match many earthly fisheries. The paper and the entire set of postings on anomaly hunters can be reviewed at parrotopia.org enjoy the read.

George Haas has done some amazing work, identifying compelling evidence of ancient architecture on Mars. Fascinating material

The geoglyphic structures we have found on Mars can be easy to miss. They tend to be incorporated into the surrounding terrain so as to blend in. If one has trouble seeing the parrot, I would suggest doing a side-by-side with George’s drawing.

As someone who has spent decades exploring the intersections of ancient symbolism, lost civilizations, and potential off-world influences, I find George Haas’s research not only compelling but vital to the broader conversation we should be having about planetary archaeology and the legacy of intelligent design—on Earth and beyond.

The Parrot Geoglyph in the Argyre Basin deserves serious attention. George and his team’s multi-disciplinary approach — blending planetary imaging, anatomical analysis, geological studies, and comparative iconography—demonstrates both rigor and vision. Whether one agrees with every conclusion or not, the data and visual evidence speak for themselves. What’s being offered here is not speculation, but an invitation: to reconsider the story of Mars through a new lens.

I encourage fellow readers and researchers to approach this work with open curiosity. These are the kinds of inquiries that push boundaries and challenge paradigms. Let’s support bold thinkers like George who are willing to walk the frontier, even when the establishment stays silent.

– Richard Smith, author and researcher

A Review of the Parrot Geoglyph of the Argyre Basin on Mars

In The Parrot Geoglyph of the Argyre Basin on Mars, George J. Haas presents a compelling and well-documented case for the existence of an avian geoglyph formation on the Martian surface—one that challenges conventional interpretations of planetary geology and invites serious reconsideration of Mars’ potential archaeological history.

Haas, known for his work with the Cydonia Institute, brings a rigorous multidisciplinary lens to his research, combining high-resolution satellite imagery, geological data, and anatomical verification from a veterinary science team. The result is a striking argument: that the formation, photographed multiple times by NASA’s Mars Global Surveyor and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, is not a product of mere pareidolia or geological coincidence, but a deliberate design—resembling a terrestrial King Parrot in both form and anatomical detail.

What sets this paper apart is its structured methodology. Haas doesn’t lean on speculation or artistic imagination alone; instead, he provides clear photographic evidence, outlines morphologic correspondences with Earth-based avian species, and references terrestrial analogs in Mesoamerican culture and geoglyph construction, such as the Nazca Lines and Maya urban design. He invites the reader to examine the evidence critically, not dogmatically.

Importantly, the article doesn’t claim definitive proof of intelligent life on Mars—but it does demand a reevaluation of how we approach such anomalies. The scholarly community has long struggled with a bias toward uniformitarian explanations, often dismissing anything outside the accepted paradigm. Haas’s work pushes back against that tendency, not with sensationalism, but with thoughtful, data-driven analysis.

In a time when planetary science is advancing rapidly and public interest in extraterrestrial archaeology is surging, Haas’s article is timely and relevant. His work stands as a call to the scientific establishment to stop looking away from high-quality anomalous data and start investigating with the seriousness it deserves.

Whether one is a staunch skeptic or an open-minded explorer of planetary mysteries, The Parrot Geoglyph of the Argyre Basin on Mars is essential reading. It reminds us that the cosmos may still hold secrets—etched not just in stars, but in stone.