I recently came across an interesting argument claiming that the capital city of Atlantis was unrealistically large based on the diameter of its outermost wall. Relying on the popular interpretation of Plato’s account which establishes a fourth circular wall having a diameter of 14.5 miles (23,5 kilometers), the argument was put forth in the form of a simple question:

"The total area of the royal city of Atlantis (443 sq.km) would have been so great that it exceeded that of today’s London with 303 sq.km and 3,2 millions of inhabitants. Atlantis – a city greater than today’s London?"

Meanwhile, Jim Allen of ‘Atlantis in Bolivia’ fame also addresses this fourth wall arguing on his website that the existence of this wall invalidates my proposed location of the capital city in South America’s Paraná Delta since the wall would have extended so far out beyond the city complex so as to straddle the very wide confluence of the Paraná and Uruguay Rivers not just once, but twice, which I agree would have proven one of the greatest engineering feats of the past and the most puzzling.

However, the biggest problem with both of these concerns exists at their very core, that an extensive fourth wall was ever truly described. This article addresses this very common misconception that actually originates with the English translation of Plato’s account where the translators had a bit of trouble juggling context. Regardless of whether or not Atlantis existed, Critias, the individual providing the original description, would have had a clear vision of what he was attempting to portray, and the following analysis will take a closer look at the text and help convey that original vision.

Here is the passage in dispute:

"[117d] And after crossing the three outer harbors, [117e] one found a wall which began at the sea and ran round in a circle, at a uniform distance of fifty stades from the largest circle and harbor, and its ends converged at the seaward mouth of the channel. The whole of this wall had numerous houses built on to it, set close together; while the sea-way and the largest harbor were filled with ships and merchants coming from all quarters, which by reason of their multitude caused clamor and tumult of every description and an unceasing din night and day." – Critias by Plato; translations by R.G. Bury unless otherwise noted.

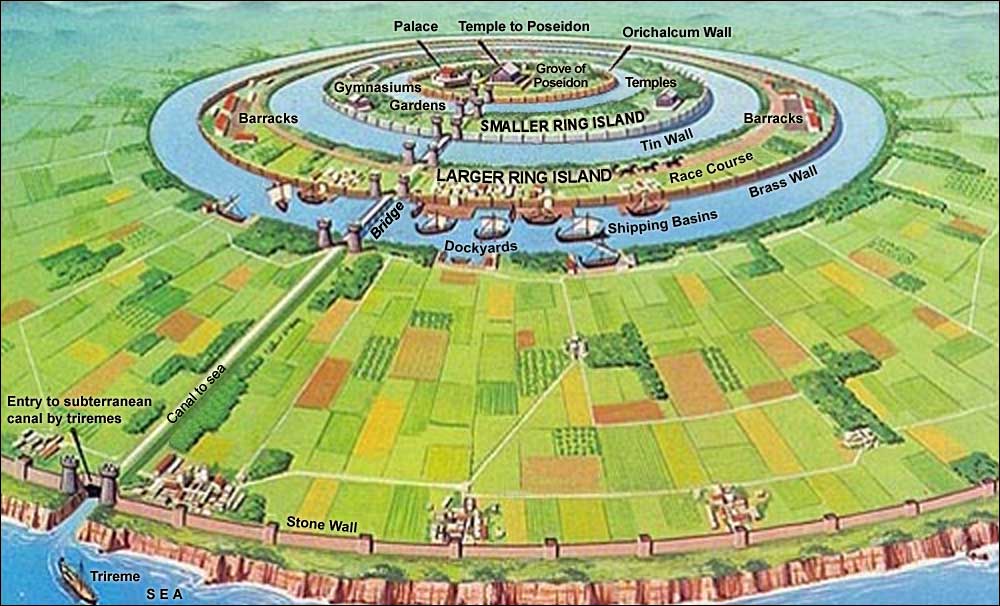

It would appear from this translation that Critias was indeed describing a wall that fully encircled the circular capital city, paralleling its outermost ring at a distance of 50 stades (5.7 miles/9,2 km) with the ends of the wall converging at the sea. (Fig. 1) With the multi-ringed city having a diameter of 3.10 miles (5,0 km), this would put the wall at 14.5 miles (23,4 km) in diameter and over 45 miles (72,4 km) in circumference.

Certainly an impressive structure, yet one based on an imagined fourth wall, where clearly the original account defines only three walls.

First of all, let us consider the first portion of the passage:

"[117d] And after crossing the three outer harbors, [117e] one found a wall…"

It is clear that the translator is suggesting that ‘after crossing the three outer harbors, one found a wall’ lying 50 stades from the city at the sea, but contextually this is wholly incorrect. After crossing the three outer harbors one actually came to the mouth of the 50-stadium channel within the outer harbor, not at the sea, but more importantly one did indeed come to a wall, a wall lining ‘the largest circle and harbor’, one of three walls existing in the multi-ringed city. This conforms with an earlier passage where Critias states that the outer harbor or outermost circle was lined with a brass covered wall:

Figure 2 – This image demonstrates the correct placement of the three walls directly in and around the city complex. The wall of brass surrounded the ‘outermost circle’ of water, or harbor. The tin wall followed next, lining the outermost circle of land followed by the wall of orichalcum which surrounded the citadel, the central island.

"[116b] And they covered with brass, as though with plaster, all the circumference of the wall which surrounded the OUTERMOST CIRCLE."

Now many have incorrectly assumed that this brass wall surrounded the outermost circle of LAND as indicated in figure 1, but without this portion of the account specifically stating whether this circle was associated with ‘land’ or ‘water’ we must adhere to contextual consistency and check other references to this ‘outermost circle’ to make that determination. And Critias’ only other reference to the ‘OUTERMOST CIRCLE’ is clearly regarding the outermost circle of WATER or harbor and occurs just a few scant sentences earlier meaning it is highly doubtful that Critias would affix two different meanings to a unique phrase addressed within a single continuous thought:

" [115d] For, beginning at the sea, they bored a channel right through to the OUTERMOST CIRCLE, which was three plethra (303 feet) in breadth, one hundred feet in depth, and fifty stades (5.7 miles) in length; and thus they made the entrance to it [obviously the harbor] from the sea like that to a harbor by opening out a mouth large enough for the greatest ships to sail through."

"[116b] And they covered with brass, as though with plaster, all the circumference of the wall which surrounded the OUTERMOST CIRCLE; and that of the inner one they coated with tin; and that which encompassed the acropolis itself [116c] with orichalcum which sparkled like fire."

So this establishes that there was a brass clad wall lining the outermost circle of water, but let us take a quick look at the positioning of the remaining two walls. Critias specifies the location of this outermost brass wall and the location of the orichalcum wall he places on the small central island or acropolis, but he refers to the tin wall as merely ‘the inner one’. Benjamin Jowett provides a translation with a slightly more specific location for the tin wall:

"The entire circuit of the wall, which went round the outermost zone, they covered with a coating of brass, and the circuit of the next wall they coated with tin, and the third, which encompassed the citadel, flashed with the red light of orichalcum. – Translation by Benjamin Jowett"

This would place the tin wall as an inner wall next in a sequence that begins with the brass outer wall and ends at the central orichalcum wall. If the brass wall had surrounded the outermost ringed island as many believe and the orichalcum wall surrounded the central island, this would establish a set or pattern of wall bound islands and therefore ‘next’ in this sequence would most definitely be discerned as the smaller ringed island. Figure 1 again demonstrates this common placement for the tin clad wall on this smaller ring of land.

However, since the brass wall actually surrounded the outermost ring of water and the orichalcum wall surrounded the central island, the sequence is not limited to the placement of walls around islands, but rather all delineations between rings of water and land become part of the sequence. Thus ‘next’ in the series after the brass wall would be the next delineation between land and water, establishing that the outermost circle of land was bounded by the tin clad wall, which coincides with the narrow channel through this island which restricted passage to a single trireme, demonstrating the secure exclusive nature of the three islands intended for military and royalty while the outer harbor and channel could be fully accessed by civilian merchant ships. Figure 2 therefore represents the definitive positioning of the three walls of Atlantis’ capital city.

Based on this corrected layout, here again we find that after crossing the three harbors we come to a wall as was stated by Critias. If the wall being spoken of was a fourth located at the sea 50 stades from the third outer harbor, instead of stating:

Figure 3 – Common misconception of a fourth wall lying 5.7 miles from the city complex and completely encircling it. Interaction between those living on this outer wall and the merchant ships filling the canal would have been minimal, limited to the entrance of the channel while there would have been absolutely no interaction with the ships in the city’s outer harbor, seemingly conflicting with Plato’s account.

"And after crossing the three outer harbors, [117e] one found a wall…"

It would have been more accurate to have stated:

"And after crossing the three outer harbors [and passing through the channel] one found a wall…" Or perhaps even "And after crossing the three outer harbors one found [the first of two walls…]"

But here is the clincher. If there was a fourth wall and it never came closer than 5.7 miles from the multi-ringed city and its outermost harbor, instead only coming in contact with a small portion of the channel at its seaward mouth as that misinterpretation maintains, portions of the passage would seem a bit disconnected and unnecessarily added.

"[117e] The whole of this wall had numerous houses built on to it, set close together; while the sea-way and the largest harbor were filled with ships and merchants coming from all quarters, which by reason of their multitude caused clamor and tumult of every description and an unceasing din night and day."

Contextually the surrounding text is focused on a description of the wall and it follows that this final portion of the passage addressing the endless clamor should also pertain directly to the wall, describing the constant interaction between those dwelling on the wall and the merchant ships that filled both the outer harbor and the 50-stadium channel.

The only such interaction with the alleged fourth wall would be limited to a very small area at the mouth of the channel near the sea. And in fact if there were guard towers located on both sides of the entrance into the channel then there would have been virtually no interaction between those that lived on the wall and the merchant ships entering the channel. We would have to assume that an extremely small group of people living on the wall were generating an ‘unceasing din night and day’ for all the city at all times of the day. It also makes little sense for Critias to mention the merchant ships in the largest harbor since they would not have been visible at all from any point along this vast wall, let alone for those dwelling on the wall to become so ecstatic about their activity 5.7 miles away.

At the bottom of figure 3 you can see how truly isolated this fourth wall would have been from the ships entering the channel and especially from those ships in the outermost harbor. If you look closely the little white specs on the blue water represent ships of about 120 feet (37 meters) in length, a general size for Greek triremes used merely to provide a sense of over all scale.

However if the wall being described was indeed the one encircling the outer harbor, one can easily imagine nonstop day and night activity where the people inhabiting space on the wall would be actively involved in trade with merchant ships in the harbor.

Figure 4 – The true configuration of the three walls of Atlantis conforming to Critias’ linking heightened day and night interactivity between inhabitants on the wall and merchant ships in both the outermost harbor and within the 5.7-mile channel. It also clarifies Critias’ original vision, "After crossing the three outer harbors, one found a wall which originated at the sea a distance of fifty stades from the largest circle and harbor; It ran round everywhere with its ends converging at the seaward mouth of the channel."

But what of the comment that the wall existed a ‘distance of fifty stades from the largest circle and harbor’? Since, as we established, Critias is referring to the wall surrounding the outer harbor, it becomes clear that he is describing the full extent of this same wall explaining that it extended out beyond the outer harbor the length of the canal to the sea or as he plainly states, "one found a wall which began at the sea" not a wall located at the sea. (Figure 4) And again this fits perfectly with the context, first of all reaffirming that the channel to the sea was 5.7 miles in length and then explaining the interaction in the channel between those who dwelt on the wall with the merchant ships. This leads to my interpretation of the passage which proves contextually more consistent, maintaining focus on the wall’s significance by linking interaction with trade ships in both the channel and harbor to the entire length of the wall:

"And after crossing the three outer harbors, one found a wall which originated at the sea a distance of fifty stades from the largest circle and harbor; It ran round everywhere with its ends converging at the seaward mouth of the channel.

The whole of this wall had numerous houses built on to it, set close together; while the sea-way and the largest harbor were filled with ships and merchants coming from all quarters, which by reason of their multitude caused clamor and tumult of every description and an unceasing din night and day."

This is indeed the layout of the three and only three walls described by Critias and portrays most accurately the outer wall as he envisioned it. Contextually all the elements align perfectly. He conveys his vision by describing crossing the three harbors, bringing himself and his audience to a wall along the outer harbor in front of the 50-stadium channel. From this vantage point a separate wall 5.7 miles away would have been too far removed to have even been mentioned. In fact, since the sides of the land rings were said to be higher than the ships in the harbor, most of this remote wall would not have even been visible from this point.

"Moreover, through the circles of land, [115e] which divided those of sea, over against the bridges they opened out a channel leading from circle to circle, large enough to give passage to a single trireme; and this they roofed over above so that the sea-way was subterranean; for the lips of the landcircles were raised a sufficient height above the level of the sea."

However with this new interpretation all mentioned elements are suddenly in play and visible from this one single location. Crossing the outer harbor and sitting in front of the entrance to the channel, Critias’ audience could simultaneously perceive being fully surrounded in the harbor by a brass clad wall while also envisioning this great structure extending far down each side of the 5.7-mile channel. From this same vantage point, we are also able to envision the many merchant ships moving about both the harbor and the channel—both lined with docks accessible from the wall similar to the portrayal in figure 1—and realize the great amount of excitement the ships’ presence would generate for the multitude who dwelt on the wall, ‘clamor and tumult of every description and an unceasing din night and day’.

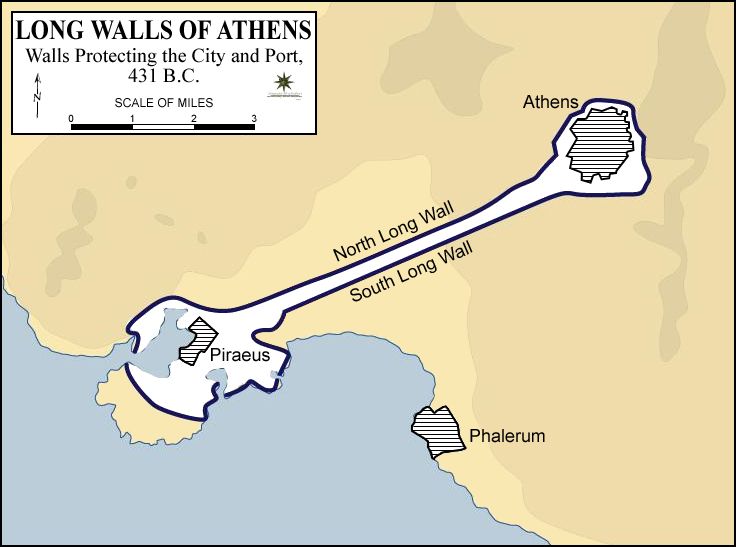

Figure 5 –

The Long Walls of Athens as they existed at the time

of the Peloponnesian War. Similar to the walls of Atlantis they provided a

secure narrow corridor through which the city was able to maintain access to

the sea.

Adding substantial credibility and practicality to this proposed layout is the existence of the similarly fashioned Long Walls of Athens. (Figure 5) Like the walls of Atlantis, the Long Walls of Athens encircled the city and extended out forming a long narrow corridor to the sea. The only difference being that Athens’ passage was of land while Atlantis’ passage was of water. Similar long wall constructions were established throughout Greece as a means of securing access to the sea. In the case of the Long Walls at Athens, the walls secured a 40-stadium (4.5 miles/7 km) passage to the port city of Piraeus from where supplies could be safely transported to the city of Athens in times of land siege.

Of course this shared attribute between Atlantis and Athens also introduces an interesting chicken versus the egg debate. If the Atlantis saga is true, could Solon’s description of its city walls, which Critias claimed to be recounting, have influenced the building of the Long Walls a century later, or if either Plato or Critias invented a fictitious Atlantis, did they base the design of its capital city on the Long Walls which existed in their day?