The Unsung Serpent

The Use of Venom in Ancient and Modern Initiation Rites

From the ancient caves of southwestern France, to the stone pillars of Anatolia, humans taking flight into “other worlds” are often portrayed with concomitant erections. Though universally linked to symbols of fecundity within the physical realm, I can assure you these are no garden-variety erections. This is a condition deeply rooted in spiritual iconography and altered states of consciousness, a telltale sign of the perilous journey initiates take as human consciousness passes through the valleys of fear, the gates of death, and is brought forth into higher awareness—venom as psychopomp.

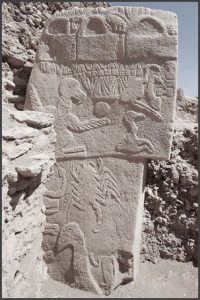

Dating back 11,500 years and counting, a headless man with an erect phallus is archived in stone upon Pillar 43 within the megalithic site of Gobekli Tepe located in southeastern Turkey. Above this curious image, ancient iconographers carved celestial markers accentuating a cosmic event that occurs once every 25,920 years. This rare, cyclical alignment happens when the December solstice sun aligns with the center of our galaxy, between the constellations of Sagittarius and Scorpio.i A sphere is carved into this very region upon this pillar that, to all appearances, represents the disembodied consciousness of a headless, ithyphallic man below in alignment with and participating in this cosmic phenomenon—the prehistoric phallus uncensored by modern decorum.

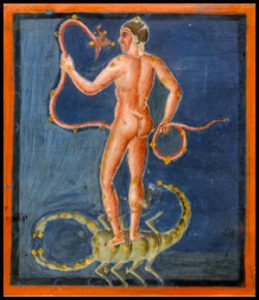

Straddling above and between Sagittarius and Scorpio bides the troublesome constellation Ophiuchus, the serpent handler. The Babylonians recognised Ophiuchus as the thirteenth zodiacal sign, though ousted at some point in favour of a more symmetrical division of twelve equal territories of thirty degrees each. Owing to the precession of the equinoxes, a rotational shifting of the Earth’s axis one degree every 72 years, Ophiuchus, today, is consuming more visual time aligned with our sun and cannot be so easily banished from the sky drama, or from our psyches for that matter.ii

Pillar 43, enclosure D, Gobekli Tepe. Klaus Schmidt, German Archeological Institute, Orient Department.

Remembering that we named the stars after our own human dramas, from the most heightened states of enlightenment down to our most base, the story portrayed on this pillar is consistent with the seemingly ageless, cross-cultural iconography of a universal death and resurrection meme. This motif, in one aspect, follows the sun as it falls below the western horizon to its rise due east each morning.

In falling into sleep each night, both mind and body encounter an altered state of consciousness. REM sleep has been called paradoxical for good reason. In effect, our muscles are completely paralysed except those of heart, breath, and vision. At odds with reason, cerebral and spinal cord blood flow increases, while glucose and oxygen uptake rises, suggesting a more global phenomenon in neural activity than fixed upon any regional function.iii Essentially, we are more awake and aware when we are paralysed in REM sleep than when we are moving about in our worlds. During paradoxical sleep, nocturnal penile tumescence is a periodic phenomenon occurring in all men whose erectile function is intact.iv As with men, women experience a version thereof, independent of erotic thought; more a consequence of moving through certain brainwave patterns and frequencies.

There was a story some years back about a Tibetan monk’s member reaching ecstatic heights while in deep meditation, most likely an effect of this change in brain wave activity. In a heroic, though tragic attempt to detach from what he perceived as earthly passion, this misguided monk traumatically removed his penis with a machete, refusing to have it reattached.v A clever Buddhist blogger responded, “This monk has got it all wrong. He’s supposed to shun attachment, not reattachment.”vi How true!

From remote antiquity, there has been a mystical alliance between the archer, the arrow, the scorpion, venom, gods and man. Sagittarius is so named from the Latin sagitta, meaning arrow. The Greek word for arrow is derived from the root toxon, or poison. The conceptualisation of this magnificent constellation as a ‘teapot’ asterism, to which it is sometimes referred, serves to drastically diminish its transformative power; that is, the subtle alchemical metaphor of a teapot serving as a vehicle for changing states of matter through the application of heat is grossly unappreciated by the western mind. Metaphorically, it seems we need the drama of a more heroic undertaking than simply boiling water.

In many germanic languages, poison is the equivalent of the English word for gift. The roots of our Indo-European ancestral language ascribe both as deriving from wen—to strive after, wish, desire, and venom, venerate, and Venus. It happens that the sting of certain scorpions brings about a prolonged erection known as priapism, though as with REM sleep, is unrelated to any thoughts of romantic desire.vii

Scorpion venom also accelerates the rapid firing of neurological impulses.viii By virtue of an increase in action potential, we also realise the overwhelming chemical effects of fear on the sympathetic branch of our autonomic nervous system, a primitive physiological response more commonly known as ‘fight or flight’. This is an involuntary and uncontrollable part of our survival mechanism: the heart palpitating at ever increasing speed and syncopation, sweaty palms, dilated pupils, trembling hands and supernal strength—a rush of pure adrenaline.

As sure as Cupid’s ‘poison’ arrow pierces the boundary of our skin, entering our bloodstream and announcing that we are no longer in control, ancient rituals used the chemistry of fear within our own bodies as a great initiator. Anecdotally, it has been told by those who have experienced the higher rites of mystical initiation that one’s electrical or frequency potential is inescapably challenged as much as psycho-spiritual dynamics.

Linguistically, the word ‘fear’ has roots in such notions as ‘to lead over…to press forward.’ The ancients incorporated five of the foremost phobias of all time into their initiation rites to quicken specific effects upon mind and body: arachnophobia (spiders and scorpions), ophidiophobia (snakes), trypophobia (holes), claustrophobia (small spaces), and cynaphobia (dog-like creatures). I found it an interesting commentary on our cultural conditioning that a 2017 ‘top ten’ list of phobias had no mention of thanatophobia (fear of one’s own death), the taproot of all aforementioned.ix It’s so deeply buried, we recognise it not.

Many feel the ancients were obsessed with death, particularly the Egyptians. They were, more so, obsessed with understanding life. Metaphors were not frivolously employed in terms of real-life spiritual pursuits. They went for the uncommon gold, attempting to receive the utmost reward for their spiritual endeavours. The Egyptian barque was no ship of fools with a dysfunctional crew. Quite contrarily, initiates underwent many extreme trials and tribulations in effort to master their own response to fear with integrity, temperance, and fortitude. In so doing, they caused a condition upon which a portal aligned, opening a gate through which consciousness moved beyond its sensory borders. One of the most highly esteemed barques in Egyptian mythology was the vehicle that carried a deceased pharaoh across the vast Milky Way to his godhood amongst the immortals.

This quest for immortality has driven and shaped civilisations since time without end. It seems the quest itself is what is reliably eternal. In today’s culture, we see this crusade manifest as a desire to remain young, remove the furrows from our brows, lengthen our telomeres, lift our breasts, manipulate our hormones, and live as long as we possibly can by whatever means technologically available. It is an earnest compulsion that has been culturally misappropriated, the last-ditch attempt to hold onto an unchanging material form. When we begin to age, this compulsion grows exponentially. We are forced to face the image in the mirror, panicked by the foreshadowing of our inherent mortality and the lapse of attention given to this predicament while still alive.

The ancient initiates had the same compulsion, though they understood that it was the consciousness of man that needed work. This impulse gave birth to the mystery schools of old, a treacherous curriculum of study and field work with rather exalted criteria for graduation. The great Sufi master, Algazel, describes this chemistry of the soul as seven formidable valleys through which one must triumphantly pass: the valleys of Knowledge, Turning Back, Obstacles, Tribulations, Lighting, Abysses and Praise.x By whatever method employed—subterranean chambers and labyrinths, pyramidal sarcophagi, reclusive caves, arctic mountaintops, alchemical marriage, or crucifixion—all are part of ‘The Great Work.’ The Sufis refer to this as “the refinement of consciousness,” a transfiguration that must occur prior to death, in pursuance of reaching the fulfilment promised in the afterlife—immortality—in becoming a god oneself, as it were.

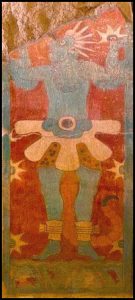

A diverse proliferation of gods in antiquity are portrayed as having luminous blue skin: Vishnu, Rama, Krishna, and Kali of Hinduism; the Egyptian gods Osiris, Hapi, and Amun; Chaahk and Tlaloc from the cultural Mesoamerican region, to name just a few. The refractory nature of the colour blue exemplifies the dissolution of all physical boundaries—the infinitude of the sky and the unknowable depths of the oceans. We are compelled to reach into these depths, though we can never fully grasp the magnitude of this frequency.

From the first time fragments of lapis lazuli were separated from their earthen home in the high mountains of Afghanistan, the colour blue was codified as most sacred within the human-visible light spectrum. Eventually, this blue stone found its way to ancient civilisations where it was allied with gods, conceptualised as a visible representation of spiritual attainments, of transcendence and immortality—the transformative philosopher’s stone of ancient alchemy.

Historically, blue has been the most difficult and costly colour to materially reproduce. The oldest known synthetic blue pigment was formulated from an intensely heated alchemical admixture of quartz, copper, alkali, and lime, conceived by the ancient Egyptians and fittingly named Egyptian blue. The term for it in their language is hsbd-jrit, meaning artificial lapis lazuli, as they made a clear distinction between ‘true blue’ and their synthetic preparation.xi

Egyptian blue pigment was discovered within the recesses of an alabaster bowl, incised with the hieroglyphic name of the predynastic King Scorpion. This artefact resides in the ‘Ancient World’ collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.xii Rather small and unpretentious, one could easily stroll by this object without notice. The discovery is notable, however, in that this bowl has recently been dated to 3250 BCE. Egyptian blue pigment had been thought by scholars to have developed much later in Dynasty Four (ca 2500 BCE). As such, this evidence grants a sophistication to predynastic Egypt that had been hitherto unacknowledged by academia.xiii

In many ancient artefacts today, this pigment is so timeworn that it’s completely invisible to the unaided eye. The chemical constituents therein, however, have certain unusual properties. Egyptian blue pigment emits an intense infrared radiation when photographed with a modified camera, transforming the images from invisible light realms into the visible world—radiantly glowing with a white, ethereal luminescence.xiv This is truly amazing to behold, as if the ‘Shining Ones’ are re-emerging from their mythical origins to manifest in our world today, still radiating five millenniums later, on artefacts and temple walls.

Both infrared and ultraviolet wavelengths fall just outside of our visible light spectrum. It so happens, in the darkness of the desert night, scorpions fluoresce a vibrant blue to blue-green colour when exposed to ultraviolet light. Within the thickly plated cuticles of their exoskeletons, a chemical reaction occurs whereby invisible light is absorbed and transformed into a visible wavelength of light, exhibiting a kind of blue-green radiance.xv Some hypothesise the eyes of the scorpion are supremely sensitive to light and can absorb and amplify radiation from the moon and stars, transforming their entire bodies into one giant light collector—a single operative eye.xvi Living on this planet for over four hundred million years, physiological and molecular adaptations have endowed the scorpion with a dramatic capacity to enhance light.

Blue Scorpion in UV light CC BY 3.0

Beta-Carboline was found to be present in the scorpion’s exoskeleton, cited as one of the chemical agents responsible for its fluorescence.xvii This is a prototype of a class of compounds known as B-carbolines that one may recognize as an alkaloid having psychotropic effects, as well as potentiating the hallucinatory effects of orally ingested dimethyl tryptamine (DMT) by the inhibition of mono amine oxidase (MAO) in the gut.xviii We’re most familiar with these chemical concepts through the Amazonian shamanic brew ayahuasca, a libation that expands the human mind to the extent where the perception of color is remarkably enhanced, barricades surrounding our sensory world are chemically put asunder, and we roam the cosmos as unbridled consciousness. Experientially, we become the color blue. Such is the nature of DMT, an endogenous chemical found within our own physiology, but given an enormous kick when administered exogenously.

Scorpion exoskeletons bathed in an alcohol solution transfer the chemical agents of fluorescence to their liquid medium, including Beta-Carboline.xix I am speculating whether the alchemical formula for Egyptian Blue pigment contained a secret ingredient—the crushed exoskeleton of scorpions, or the liquid medium in which they bathed. After all, formulators of any acclaimed recipe are always remiss in sharing that one special ingredient that sets their creation apart from others. I am also wondering whether the ingestion of this Beta-carboline from scorpions co-administered with Acacia, a sacred tree of the Egyptians containing DMT, was responsible for the ancient initiates’ capacity to receive knowledge from worlds beyond, through certain electromagnetic frequencies and wavelengths that reach beyond our customary limits.xx

King Scorpion, detail from his mace head. Protodynastic period. CC BY 3.0

Not much is known of these predynastic Scorpion Kings. There is a mace head featuring a scorpion and a seven-petaled star or flower-like formation, an emblem of divinity attributed to King Scorpion II, who was antecedent to and an inspiration for future dynastic kingdoms. The scorpion may not have been a personage at all, but perhaps a title that was bestowed upon kings from the Proto-dynastic period of Upper Egypt. Is it possible that the seven-petaled flower above the scorpion on this mace head was representative of the fruit of the Tree of Life containing DMT, while a physiological MAO inhibiting companion was found in the scorpion?

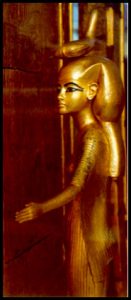

The predynastic King Scorpion is identified by the insignia srqt. The Egyptian scorpion queen Serqet later became patron to and protector of the dynastic pharaohs. She is one of the earliest and most intriguing scorpion deifications of antiquity, a goddess of venomous creatures, medicine, magic, childbirth and protection. She appears as a beautiful woman with a slightly tumescent belly, arms outstretched, with a scorpion upon her crown. Beyond the scorpion, her symbols include the Ankh of eternal life, and the Was Scepter of divine power and authority. Her presence is most renowned for being one of the four gilded goddesses protecting Tutankhamen’s tomb. Coincidently, Tutankhamen’s mummy was found with his member erect at a ninety-degree angle.xxi

Anatomically, the scorpion’s head and thorax are merged together. The female’s birth canal is located near the centre of her chest, a place we would anthropomorphically conceive her heart to be. Their young are born live, and appear as if emerging from her heart centre, cleaving to her breast before mounting her back. Some species of scorpions can reproduce asexually through parthenogenesis, essentially birthing their young into the world while still maintaining a virginal stature.xxii xxiii

Antares, the brightest star in the constellation of Scorpio (a red, flaming, super giant) is known as the heart of Scorpio. As one of the four ‘Royal Stars of Persia’ fixed upon and guarding the cardinal directions, Antares is the ‘Watcher of the West’ and the gateway to the underworld associated with the autumnal equinox and death.xxiv Antares is a provocateur to the star Aldebaran, the right eye of the bull in the constellation Taurus, the ‘Watcher of the East,’ associated with enlightenment and the vernal equinox. They are positioned opposite each other in the night sky, each one rising while the other sets. And though Antares has incurred a bum rap being mythically aligned with death, Aldebaran and Antares, the bull and the scorpion, are more of an opposing yet complimentary dynamic within the same dualistic nature of a balanced, unified whole.

Within the iconography of Artemis of the Ephesians, the scorpion and the bull are brought together once again. Unlike the generic Artemis with whom we are delightfully accustomed—a beautiful bow and arrow bearing, scantily clad, wildly undomesticated, virgin huntress with a mean streak—the Ephesian Artemis differs profusely in almost every aspect. Her very name has been interpreted as ‘Artemis Saviour,’ and according to Strabo’s Geography, written in the time of early Christianity, Artemis received this title as meaning ‘sound, well, or delivered,’ etymologically rooted in such notions as to save, rescue, set free, and liberate.xxv This is a testament to her mythological beginnings where immediately after her own birth, she turns to assist her mother, Leto, through the difficult delivery of her twin brother, Apollo. For this, she is associated with midwifery, childbirth, protection, and transitions.

Statue of the type of the Artemis of Ephesus, Naples National Archaeological Museum. CC BY 2.5

A comparison can be made between the statuary of the Ephesian Artemis and that of the terrestrial scorpion. Her most unusual vestments are her darkened skin and the hanging ovoid sacs upon her chest. These sacs, once argued by scholars to be anything from bull’s testicles, to breasts, to eggs—all have been found, in one form or another, within varying mythologies consistent with the scorpion’s encoded symbolism.

As we read in Hamlet’s Mill, “corresponding to the Egyptian scorpius-goddess, Selket, and to ‘mother scorpion’…dwelling at the end of the Milky Way, where she receives the souls of the dead; and from her, represented as a mother with many breasts, at which children take suck, come the souls of the newborn.” The same symbolism can be found in Maya mythologies, with the “many breasted old goddess with a scorpion tail, and Itoki, the Mother Scorpion goddess of Nicaragua and Honduras—all residing at the end of the Milky Way and associated with death and birth transitions.”xxvi

Intriguing is the celestial corollary to these ancient mythologies within the open stellar cluster Pismis 24; blazing from the core of a nebula within the constellation of Scorpio, it is one of the most fertile cosmic-nurseries in our Milky Way, producing some of the largest stars ever discovered.xxvii Today, this phenomenon can only be visualised through highly advanced technology, and even so, obscured by veils of gases and dust swirling around this celestial mother scorpion. Could the ancients have seen what is unauthorised by the limits of our perceptual apparatus today?

Nebula in the constellation of Scorpio: Pismis 24. CC BY 4.0

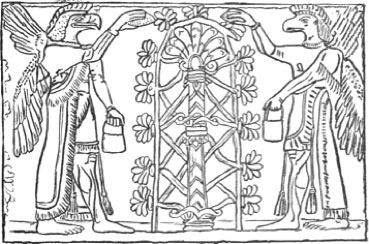

As an archetypical template, scorpions are frequently placed at gateways and pillars, protecting the sacred space beyond from casual entry. The Epic of Gilgamesh, a tale with roots stretching back to ancient Sumer, narrates Gilgamesh’s search for immortality. He is challenged by Scorpion-men, gatekeepers of the sun god Shamash, “whose radiance is terrifying and whose look is death,” flanking the mountains of Mashu. These were fierce, venomous warriors, who keep watch at the sun’s gates upon its rise and descent.xxviii

Let us be reminded of the Hermetic tenet “as above, so below.” In terms of initiatory practice, priestess/priest and physician were once unified within the same profession, attendant to the triad of spiritual, mental and physical needs of their communities. There was no division. There was no lack of perception uniting these shifting energetics between mind, body and soul. Conforming to the law of correspondence between dimensional layers, any soulful attainment or infliction on the spiritual plane has a twin cast within our biology and physiology, and vice versa. The rise of secularization fragmented this integrity—compartmentalizing body, isolating mind, and shattering the soul into modern oblivion. Ancient initiation rites addressed the whole of a person, from the vitality and overall strength of the physical being, to a more cosmic consciousness in relationship with the divine.

So how did the ancients provide an initiate the means to move beyond the root of all fear, leading them over, pressing them forward?

There were three primary rituals of initiation: understanding body, understanding mind, and experiencing pure consciousness. The ‘lesser’ mysteries relate more to physicality, meant for the masses and conceived to promote fertility. The ‘greater’ mysteries used psychotropic agents to assist in understanding mind. The third rite, the ‘greatest’ mystery, the one never spoken of without enormous penalty, was the experience of death, allowing us to know ourselves unconditionally, apart from body and mind. And I suspect there was no feigning of death within the innermost mysteries. I am reasoning that an actual experience of death may have been gifted through a small dose of intentionally administered venom.

Many venoms have neurotoxic constituents, particularly scorpion, cobra and viper. These molecules block our neuromuscular synaptic gates. As the venom circulates through our blood, more and more gates are obstructed, completely impeding communication between brain and body, paralyzing our muscles. Death eventually ensues when this effect reaches our breathing muscles, causing subsequent respiratory failure.

In this speculative scenario, a priestess-physician would ‘watch over’ and breathe for an initiate’s physical body while their consciousness takes flight, much in the same way a mechanical ventilator would breathe for a patient today. The scorpion goddess Serqet was said to “give the breath of life to the righteous dead,” escorting them on their journey from, and return to, the physical domain, just as all our mythological Mother Scorpion goddesses have done throughout time. In this way, breath was bestowed externally until the effects of venom subside, at which time one is reborn into one’s own victorious first breath of a new life, a new sunrise.

With paradoxical dream sleep, we experience a similar paralysis though we still breath on our own. With a brief period of death, our neurological circuitry is reduced to the expansion of vision and heart only, as echoed in the Hall of Ma’at where one’s heart is weighed upon the scales of justice enacted in this Egyptian death ritual. Scorpio, at one time, was a much larger constellation, embracing the virgin, Virgo. The claws of Scorpio were dismembered by the Romans, becoming the scales of Libra, segregating the two.

Along with her many attributes, Serqet is regarded one of the earliest mother goddesses, depicted in the Pyramid Text as being a wet nurse to Egyptian kings. In time, she was assimilated as an aspect of Isis, the horned goddess often portrayed nursing her son Horus, and later the Virgin Mary nursing Jesus. What was once considered to be miraculously divine or purely mythological is now found as having roots embedded in modern scientific research; the venom of the Horned Viper has the toxin crotalid within its constitution, which stimulates mammary epithelial cells to secrete casein, using the same biochemical pathway as prolactin for the production of breast milk. The use of this venom may offer an explanation as to how virgins, or women who were never pregnant, were able to serve as wet nurses for the gods, saints, kings, and temple elite.xxix

Certainly, an increase in breast milk production would have a biological and evolutionary advantage during times of environmental stress. There are artistic renditions of saints suckling the breast of the Virgin throughout the ages. St. Bernard of Clairvaux, a monk and key reformer of the Cistercian order, highly influential in the formation and guidance of The Knights Templar, and eminent preacher of the Virgin’s glory, is so portrayed in ‘the Miraculous Lactation of Saint Bernard.’ Another saint, Pedro Nolasko, formed the ‘Order of the Blessed Virgin Mary’ with the mission of freeing Christians imprisoned for their beliefs. There are portrayals of chained captives, sentenced to death by starvation, whose lives were sustained by the daily visitations of lactating women who offered their breasts as the only source of sustenance connecting them to life.

In the state religion of Rome, the divine phallus (fascinus) was worshipped and tended to by the priestesses of Vesta, goddess of the hearth. Vestal Virgins were committed to the temple before puberty and required to take a 30-year vow of celibacy. Still, strangely, they were able to produce breast milk in nurturance for temple select. The Vestals attended a special college denied to the priesthood and were the cultivators and caretakers of the sacred and eternal temple fires.xxx

With so much of the bloodlines of late royal lineages open to discussion and supposition, it should be mentioned that to the ancients, breast milk was considered to be blood, and those suckling from the same breast became ‘milk-siblings.’ This milk kinship fostered alliances, particularly in hierarchical societies; the ‘milk mother’ having the vital role of nurturing relationships and unification within communities and religious orders alike. The same cultural taboos applied for milk as they did for blood, “what is forbidden by blood kinship is equally forbidden by milk kinship.” Through the all-nurturing mother archetype of the lactating Virgin, adherents of religious orders become siblings of a Saviour Child through her Milky Way, and thus regarded each other as brothers and sisters in a more literal sense than one would suspect.xxxi From a cosmic perspective, the celestial Milky Way that births and receives souls, would ultimately unite all on this planet as milk-kin.

There is also, within the biological domain, the attribute of antibody protection offered in breast milk through the process of passive immunity. If a host, whether human or animal, survives a direct bite or sting from a venomous creature, an organic response will initiate the formation of life-long, venom-specific antibodies which can be temporarily conveyed to others via breast milk. If a nursing female were to be intentionally envenomated with a controlled dose of an array of venoms—just enough to stimulate an immune system cascade similar to our vaccines today—she would henceforth develop an expansive scope of immunity against the most constant and unpredictable threat to ancient lives—venomous creatures. In this way, the ubiquitous veneration of Hathor as cow goddess in ancient Egypt may have connected her with the role of ‘host’ animal for the masses. And, coincidently, the luminous Egyptian blue pigment is found on her statuary and pillars, a designation of her heightened, sacred status.

Regardless, the question needs to be raised as to whether the sequence of ancient rites included a more occult aspect of biological informatics for healing and protection through intentionally controlled envenomations, along with the more appreciable tutoring of spiritual matters. Pharmaceutical research has been exploring the healing properties of venom for several decades now. Currently, a handful of venom derived drugs have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and are on the market, in use. Further clinical trials are finding extraordinary efficacy rates for almost every malady known to man: cardiac disease, stroke, neuromuscular disease, pain control, erectile dysfunction, diabetes, and anti-ageing, to name a few. The scorpion alone has therapeutic leads for HIV, autoimmune disorders, cancer, and malaria — patents already in hand.xxxii

Human clinical trials involving the venom from the ‘Deathstalker’ scorpion in the form of a tumour paint began at Seattle Children’s Hospital back in September 2015. It so happens that this venom has an affinity towards glial cells found in our brains, flipping inside and lighting them up, an attribute that allows neurosurgeons the ability to more precisely define a tumour’s border during real-time surgery. The result allows for less tissue damage, thereby preserving more brain function, which ultimately improves patient outcomes.xxxiii

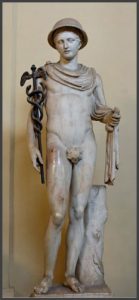

The therapeutic qualities of the serpent are intrinsically woven throughout both ancient and modern healing arts as evidenced by their chosen emblems: the Caduceus, two snakes entwined around a winged staff; and the Rod of Asclepius, a single twined snake. The Greeks, as well as many who came before, considered snakes to be sacred beings associated with wisdom, healing, transformation and resurrection—if not a symbol of the origin of life itself.

The Greek physician Asclepius was raised from infancy by the wise, old centaur Chiron from whom he learned the art of medicine. Historically, Sagittarius has been referred to as the Centaur-Archer, while Asclepius is associated with the snake handler Ophiuchus. Although mythologies abound, in one he was fathered by the god Apollo, and born posthumously from his mortal mother Coronis. His life story plays out more as one of a mortal being on a hero’s journey, where elevation to the status of a god was merited by good deeds—by healing the sick and raising the dead. The motivation for his murder was attributed to “having infringed upon the rights of Hades.” xxxiv

Many of the qualities assigned to the gods and temple elite may actually have been a result of the therapeutic efficacies of venom: supernal health and stamina, immunity from environmental toxins, youthfulness, even immortality. For it was said that Asclepius could raise the dead, not by an investment in magical power but through a deep understanding of the inherent wisdom of both mind and body; a knowledge that would assuredly hang a vacancy sign on the gates of Hades.

A caduceus, or ‘herald’s staff’ is carried in the right hand of the Greek god Hermes. Greeks living in Egypt merged the attributes of Thoth with Hermes and though each god had an array of unique, and sometimes opposing qualities, the core attributes they shared were those of wisdom, eminent healing capabilities, maintainers of equilibrium, and guides that accompanied the deceased into other worlds. Thoth officiated the weighing of the heart ceremony before Osiris, and Hermes, most notably, a messenger of the gods that could easily pass between the veil that separates the worlds.

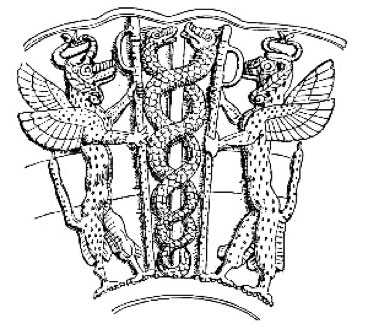

A century ago, L. A. Frothingham put forward evidence suggesting the origins of Hermes’ caduceus, two snakes twining around an axial rod, derives from the Babylonian snake-god Ningishzida. The primary function of the two-snaked god was to act as a messenger for the Mother Goddess—the source of all life whose primal embodiment is depicted as a single snake.xxxv The Neo-Sumerian ‘Libation Vase of Gudea’ of the god Ningishzida, now housed in the Louvre, is dated to approximately 2120 BCE, predating the caduceus of Hermes by more than a millennium.

The overall motif and compositional elements of this vase suggests the regenerative power and vital force of creation (the primary attribute of this god) in the form of two snakes, one male and one female, objectifying the opposing yet complimentary forces of creation. Ningishzida, the son of the heavens, was one of two guardians at the palace of Anu. His name has been translated as ‘lord of the good tree,’ also associated with the underworld and judgement.xxxvi Temples dedicated to him were called ‘houses of justice.’ Frothingham moves on to suggest the Assyrians eventually transfigured the symbolic caduceus into their Tree of Life, or Sacred Tree.

Nearly every known culture conceives a tree as being central to their creation models, envisioning an axis connecting all living kingdoms below with that of the divine, manifesting some-thing from no-thing. The word treow has identical terms meaning both tree and truth, so it follows that although the species of tree may change in place and time accordingly, commonalities are underwritten in all its forms that is rarely seen with such consistency.

In Mesopotamian thought, the king was considered the perfect man, the son of the Universal God, a sensory representation of divine cosmic principles having the role of connecting heaven with earth upon a central axis. This Son of God merged with the Sacred Tree, the tree endowing the king with the same attributes from which his kingdom was to be governed: centrality, symmetry, balance and harmony.

Flanking the Assyrian Sacred Tree are antediluvian demigods, known as the Apkallu sages, conceived as bringing the art and science of civilisation to ancient mankind through various disciplines defined by a more advanced and sophisticated culture. Researchers have discovered Egyptian blue pigment in the recesses of the stonework panels upon which these sages were carved, signifying their divine nature.xxxvii Though almost no trace of this pigment is visible to the naked eye today, these sages glow with a luminous white radiance when exposed to a ‘visible-induced-light’ technology, just as the King Scorpion bowl glowed in the research laboratory of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

For well over a century, ethnologists and botanists have proposed theories regarding the symbolism of the Apkallu sages along with the mysterious bucket and cones carried in their hands. Sir Edward B. Taylor, an English anthropologist regarded as founder of cultural anthropology, first proposed an explanation for the accoutrements and gestures of the Apkallu in relation to the Assyrian Sacred Tree, submitting his ‘Palm Tree Theory.’ xxxviii Taylor surmised the alabaster relief panels of King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BCE) displayed within the North-West Palace at Nimrud features a ritual of artificially pollinating the date palm, whereby the inflorescence of the male palm is dipped into the bucket containing pollen dust and hand delivered to the female palm flower. This technique is still employed today in some parts of the world, and looks very much like the panels of ancient Assyria, replete with cutting instruments tucked into a sash wrapped around the Apkallu’s torso; the male spathe must first be removed from the male tree by way of climbing a ladder and hewing.

Tylor’s theory was initially resisted by his academic peers who followed with some ideas of their own: a phallic and fecundity symbolism, another as a purification ritual. Whereas these three theories would find a meeting place difficult a century ago, they are beautifully interwoven as complimentary aspects of an overarching iconography of the ‘sacred tree’ which meets our cross-cultural understanding today. As so, this more likely represents a metaphorical dissemination of wisdom passing from the gods, through the king as intermediary, extending to humans, and supporting plant life, which in turn cycles back, sustaining the entire kingdom. Fertility on all levels of being — cosmic, spiritual, animal, and plant is bestowed from these blue heavenly royals, acting as divine bees.

The Assyrians may have borrowed this image from the Babylonians where the date palm grew more abundantly in a warmer climate. Here, the date palm is associated with Ishtar, who was not only the goddess of fertility, but also one of the first considered as an archetype of the Mother Goddess—she bears in hand one of the most ancient forms of a snake entwined caduceus. Scientific studies concerning the efficacy of the date palm on enhancing fertility unequivocally support this association. Research published in the Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology Advances concludes that date palm pollen facilitates sexual arousal, stimulates erections, prolongs ejaculatory latency while improving sperm quality and motility.xxxix The date palm tree would assuredly maintain the sexual potency of the king which in turn promised an agricultural abundance for all.

The formal name of the date palm, Phoenix Dactylifera, has the obvious association with the Phoenix of resurrection—a mythological bird reborn from the ashes of destruction. It also etymologically references the date, both fruit and tree. Dactyls, from the Greek word for fingers, were an archaic mythical race of male beings associated with the Great Mother, who were healing magicians that disseminated art and science to mankind.xl

Simo Paralo, a Finnish Assyriologist and professor at Hellsinki University, takes this proposal further by suggesting that a descending lineage of sacred iconography is structured upon the symbol of this fourth millennium Sacred Tree. He examines and compares the ideology of the kabbalistic tree of life as well as the symbol of the christian cross, both as representations of the relationship between a Universal God and man, the spirit’s guise in matter, along with its potential for ascension and reunion.xli

The Kabbalistic Tree projects the image of the cosmic world order as an equilibrium emanating from the transcendent God; both having a triadic symmetry of zig-zagging lines, which can be visually conceived as an abstract twining of snakes. The Sefer Yetzirah, the book of creation according to Jewish esotericism, associates the ‘ten fingers of God’ with creating this Tree of Life, consisting of thirty-two paths, ten Sefirot (digits) and twenty-two letters through which God communicates with man, and man with God.xlii

Considering the serpent is a long-held symbol of wisdom amongst all ancients, crossing many borders, it would seem the transfer of divine knowledge flowing down through the tree to man suggests that something symbolic of cosmic wisdom must be in the container held by the Apkallu sages. Curiously, the fingers of these semi-divine beings are nearly always grasping the bag in a certain way—as if the hand was so positioned in the act of milking a snake, extracting its wisdom; a symbolic diffusion of cosmic law from above, descending to below.

Along with the caduceus or tree of life in his right hand, Hermes, too, carries a container or purse in his left hand. This “purse” has provoked contention amongst the medical community as Hermes was also associated with attributes that would be considered objectionable to their profession: the god of commerce, negotiations, and trickery.xliii They call it the “fat purse” of Hermes, and argue that the Rod of Asclepius is more accurate a representation of their professional standing. Knowledge, in and of itself, is quite neutral, and can be administered to injure or to heal in accordance with the proclivity of the practitioner. But could Hermes’ “purse” contain an esoteric gold adopted by the alchemist as Mercury, the Roman version of Hermes?

Nevertheless, returning to Gobekli Tepe, rather astonishingly, we see these iconic container-purses atop Pillar 43—the same shape as those found in the hands of gods within megalithic sites around the world—but with more unambiguous symbolism: a stylised fluid flowing down from these containers towards the disembodied consciousness of an ithyphallic man, through Sagittarius and Scorpio. That is, wisdom flowing from the cosmos, through the stars, through man’s consciousness to his body. And yet, this symbolism appears millenniums prior to the date we are told by convention that the birth of civilisation occurred, within a sophisticated temple structure extraordinarily precocious for its suggested ‘hunter-gatherer’ age.

Pillar 43, enclosure D, Gobekli Tepe. Klaus Schmidt, German Archeological Institute, Orient Department.

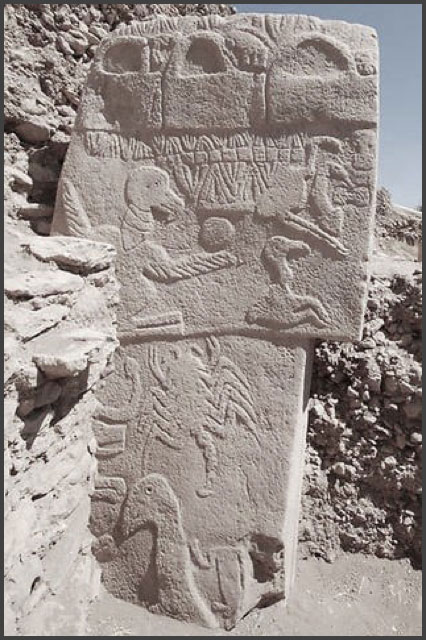

Rewinding time further back to nearly 20,000 years ago, we find the ‘Bird Man’ of Lascaux, an ithyphallic man with the head of a bird, commonly translated as a shamanic practitioner having an otherworldly experience. The image is found within an isolated natural fissure called ‘the shaft’ leading to a lower level, some refer to as ‘the holy of holies.’ His erection certainly may be a consequence of a natural or otherwise induced altered state, or perhaps hypoxia from the high carbon dioxide levels.xliv But I cannot help but pay special attention to the disemboweled bison and the unlikely evisceration from impalement of a single, narrow spear that is still plugging his gut. Though this cave painting far preceded Egyptian civilisation, disembowelment was part of the Egyptian funerary rituals, believing the bowels held poisons and venoms. Serqet was the tutelary goddess of the intestinal canopic jar associated with the West in Tutankhamen’s tomb, and we are certainly aware of the condition of his mummified member.

The roots of iconic symbolism is perplexing at best. The purpose of a masterfully designed iconic image is to penetrate more deeply, beyond appearances, into a mystery accessible to both the initiated and uninitiated eye. Oftentimes we are left with timeworn images carved into or painted upon stone with no accompanying script. This uncertainty is disturbing to our restless minds. We want to pin it down, fill in the blanks, and construct theories shaped by cultural memes intermixed with our own personal experiences, both of which have a propensity to distort truth. But these iconographic images handed down to us are designed to bypass our penned anthologies, doctrines, and dogmas—especially our own minds—in a valiant effort to reveal truth.

The most potent and recognisable religious iconography today is the image of the cross. From the most distant and isolated times of prehistory onward, the cross has enmassed a bountiful archive symbolising the union of horizontal and vertical planes. It is the Tau of resurrection; the band encircling the brow of Tammuz; the Native American medicine wheel; the eternal life of the Egyptians; the four elements; the four cardinal directions; the sign for Aldaboram, (Aldebaran) the eye of the bull; the footprint of megalithic temples and gothic cathedrals; and the rood screen partitioning the altar from the main body of the church. In terms of death and resurrection, it is a symbol par excellence.

The cross is also the geometric seed pattern of the seven-circuit labyrinth, the innermost threshold where Theseus battles his own personal Minotaur—half man and half bull—wrestling to overcome the most destructive aspects of his human nature. This archetypal drama also unfolds within the iconography of seven successive Mithraic rites, culminating in a scene where Mithras successfully slays his bull. Favourably inclined to support our theory, a scorpion is latched onto the bull’s genitals, accompanied by a snake and a dog, all proving to be faithful companions of the initiate.

The Scorpion pinching the Bull’s testicles, ‘Mithras slaying the Bull’, statue at the British Museum.

It is unlikely that bull sacrifices occurred within the space that these rites were performed, although bull’s blood was later to become a secret ingredient of an alchemical formula for creating the pigment ‘Prussian blue.’xlv Most Mithraeums were adapted from caves or built as subterranean chambers, typically to accommodate a small and intimate gathering. The interior design bore the image of the cosmos, consistent with being in a place where one must first descend into darkness, the depths of his original nature, before reaching for the fullness of Primordial Unity. Only then may one emerge anew from the labial entrance of the cave from which one entered—from light, to shadow, returning to light.

Christians adapted these labial folds in the form of a fish or ichthys, the greek word for ‘fish’ and a backronym/acrostic for “Ἰησοῦς Χριστός, Θεοῦ Υἱός, Σωτήρ”, (Iēsous Christos, Theou Yios, Sōtēr), which translates into English as “Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour,” formed from the Greek letters iota, chi, theta, upsilon, and sigma. xlvi Respectively: iota (i or j) the point of origin, chi (ch or x) the active principle where two planes cross, theta (th) as death or the unvoiced, upsilon (Y) concentration and accumulation, and sigma (S) mathematical sum. This metaphorically exemplifies in all its glory, the life and process of Christ’s birth, transfiguration, death, resurrection, and ascension in a near formulaic equation. In astrophysics and physical cosmology, upsilon ‘Y’ (concentration and accumulation) refers to mass-to-light ratio, a symbol morphologically resonant with Christ’s body on the cross.

The ichthys, or fish, is also an illustration of the vesica piscis, a symbol that served as a kind of secret handshake to early Christians who met along the path during heightened times of persecution. Vertically aligned, the fish is the archway or portal through which Christ is portrayed during his transfiguration as well as other sacred occasions, nearly always associated with the colour blue. It is this change in mass-to-light ratio that is a needed prelude to resurrection and ascension. ‘The Assumption’ or the ‘Dormition of Theotokos’ commemorates the death, glorification, and resurrection of Christ’s mother. Jesus appears through a blue ichthys. Both he and his mother are wrapped in blue. Three days later, her tomb was found empty, and thereafter she was considered the first fruits of the second coming.

The alchemical knowledge of how to prepare blue pigment was lost through much of the Roman empire. It was not until the fourteenth century, when a fragment of lapis lazuli found its way to the Venetian coast of Italy that a formula was recreated, and the colour blue resumed its mystical alliance with divinity. The church greedily restricted the supply of lapis lazuli for its own use, codifying colours, reserving blue to represent the heavens, or heavenly bodies such as the Virgin, and no other. Laws were passed prohibiting even the wearing of the colour blue by the masses—church law forbidding us the opportunity to wrap ourselves in any form of divinity, or to even imagine a spark of the divine might be seeded within us. It would be a long time until the colour blue would be “liberated from the suffocating grip of the church.”xlvii

Many church doctrines have separated carnal intelligence from its sacred alliance and in so doing, killed the soul of Eros (the longing for union with the divine) so that one intermediary might assume ‘The Great Work’ for all. The Assyrian kings whose behaviour violated the laws of governance, had to repent while undergoing a purification ritual upon the Sacred Tree. And if the sin was so great as to issue a death sentence, a man was chosen as a stand-in for the king, and sacrificially put to death in his place.xlviii One man took on the sins of the king, henceforth saving the entire kingdom from demise, just as Christ upon the cross a thousand years later.

There are many iconographers who have depicted the crucified Christ in such a way as to symbolically suggest his member was erect. We seem to acknowledge this condition in other iconic figures without particular sway, but this image hits too close to home for many. Whatever our intellectual or emotional reflex might be, this rendering is compelling within Renaissance art, demonstrating a continuity of gesture throughout both historical and mythological resurrected figures that is difficult for an open mind to deny.

Leo Steinberg, a controversial art critic, unveiled many of these paintings for public view a few decades ago in an article that later became his book The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion. Unsurprisingly, these images were met with fierce debates and quickly subverted to the realms of obscenity and perversion. Demystifying the iconography of Christ on the cross should not profane our sacred vision of this most extraordinary archetypical god-man, nor the process of universal salvation he so represented.xlix

A contemporary crucifix hangs above the altar of St. Charles Borromeo Catholic Church in Oklahoma City. The congregation was recently at war over what appears to be Jesus’ erect phallus. The iconographer based her rendition upon the 12th century San Damiano crucifixion, a treasured Catholic icon. Members supporting the image commented that it is meant to show ‘Jesus’ abdominal distension.’ Sixty-two percent of the church members found it to be inoffensive while the offended minority of thirty-eight per cent won out; the iconographer reluctantly agreed to alter her work in order to resolve the conflict within the body of the church.l How often have icons been changed throughout the ages, either diluting their sacred seed or destroying it altogether? Incidentally, this iconographer did not intentionally portray Jesus in this manner; it simply evolved naturally in the course of her devotional work, and she was appalled at the events that followed the unveiling.

Contrary to the image of the hanging devitalised Christ as the embodiment of suffering, Wolf Huber’s Allegory of Crucifixion rendered in the mid-16th century (the word allegory implies hidden meaning) shows the strength of Christ: his hands clenched in fist though riven through by nails, his spine arched and firm, his eyes open and fixed upon a stupendous loincloth billowing in the wind from which the virgin and child appear to emerge. Though strange to our understanding today, this is truly a commanding image, merging and raising sensory apparatus to heightened states of divine virility. What is this saying to us?

“The Primal elements, as it were, the passions of God’s Will desiring Himself. It is himself as Mother or Spouse desiring Himself as Father…this ‘Feminine Aspect’ of Deity is called Wisdom and Nature and Generation and Isis…that desire becoming the Primal Cause as Mother of the whole world-process, which is consummated by His Fullness uniting with his desire or Wisdom, and so perfecting it.” li

A limp serpent hangs on a cross beside the crucifixion. A cursory analysis of this lifeless serpent would likely become a conventional metaphor for the overcoming of evil forces. Biologically and mythically, however, the serpent is much too powerful a concept to be consigned to such monotony.

It has been demonstrated by researchers that both primates and serpents evolved skills in accordance with and as consequence of perceived threat. In other words, we evolved influencing each other through our vulnerabilities and fears; primates adapted higher visual centres and acuity to be able to quickly recognise a slithering grim reaper, while serpents developed the ability to mix and serve proprietary blends of toxic cocktails that target the specific bio-system of their intended victim.lii

Interestingly, the root oph is almost exclusively found with words referencing either the snake or the eye, as in ophidian and ophthalmia. In the Egyptian Book of the Dead, the sacred eye is injured on the day when the Rivals fought—Set as chaos pitted against Horus as order. As the supreme arbitrator between good and evil, one of Thoth’s many attributes is providing equilibrium. On occasion of these epic battles between good and evil, Thoth would heal whichever opponent was injured, thereby maintaining a neutrality within the kingdom, denying either one the upper hand.

The winged serpent Wadjet (with linguistic roots the same as srqt, the scorpion), also known as The Eye of Horus, is represented as a protective cobra on Egyptian diadems, one who spits venom at those who offend. Scientific researchers observing the behaviour of spitting cobras found that the distribution of the venom spat formed geometric patterns: the most common being paired ovals, but including figure eights, zigzags, and dispersion patterns of concentric circles. Various species are able to hit the eye of a target with 90% accuracy from a distance of six to eight feet, often from much further away.liii

An interesting finding concerns the shape of the target that triggered the research snakes to spit. The most extensive study that I came across used many moving targets with differentiated shapes, sizes and characteristics.liv An oval, as a representation of a face, was the target most likely to elicit a spit. The snakes showed little preference for an oval with eyes in comparison to an oval without eyes. It is theorised that venom sprayed in patterns, diffusely covering the target with broadened geometric dispersion would better ensure that at least some venom would likely land in one of the eyes.

Video simulations were failures for the most part. Unlike us, the snakes could not be easily fooled, apparently needing more depth perception to elicit an attack than a projected image on a screen. Fascinating was the snakes’ heightened restlessness when the researcher walked in front of the projection, casting a dark shadow upon the viewing area. More interestingly, triangular shaped targets were, for the most part, statistically ignored by the snakes, even when vigorously shaken and thrusted towards them. Extraordinarily, and oddly enough, one of the targets used in this study was a bird on a stick, the exact symbol we see next to the ithyphallic ‘Bird Man’ in the caves of Lascaux. This target, not once, elicited an aggressive response from the snakes.

St. Bernard of Clairvaux is not only portrayed as suckling the breast of the Virgin, but also as being sprayed in the eye with the Virgin’s milk, displaying a vigorous, long-range, and accurate trajectory—so similar to the spitting snake. The legend goes that he received wisdom when the Virgin’s milk filled his mouth and landed upon his eye. There is also a rendition where St. Bernard’s eye was physically healed of an infliction by the Virgin’s milk.

The lack of aggression displayed from the spitting snakes towards triangular targets makes perfect evolutionary sense. There are no naturally occurring, triangularly shaped enemies of the serpent. There is no reason to evolve adaptations to kill when there is no perceived threat. This opens the possibility that, through the law of correspondence, a natural protection was created energetically through the Holy Trinities within each spiritual tradition, occult or otherwise. The gods and serpents have made peace with one another within this triadic morphology: the feather, the serpent and the triangular faces of the tetrahedron, or the pyramidal complex; Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva; Osiris, Isis, Horus; Kether, Chokmah, Binah; Father, Son and Holy Ghost.

This concept more fully unfolds with the research conducted concerning the ancients’ intentional placement of sacred sites throughout the globe upon fixed points within a network of triangles.lv These are places where chaos and order are equipoised within the deeper mysteries. There is an uncanny sense of a natural energetic protection within these sacred temples that allow us to open, to engage, to see, to hear, to touch more fully, the essence of our being beyond fear, that we may know ourselves, where we come from and where we are going. These are places where feathered serpents are born, where the virtue of the equinox is exemplified through the perfection of a balanced interplay of light and shadow. The Maya engineered this concept to perfection in the magnificent pyramid of Kukulkan at Chichen Itza, on the Yucatan peninsula of Mexico. Here, on the equinoxes, through an interface of light and shadow, the illusion of a serpent slivers down the pyramid from above and meets the Earth.

Our fear of snakes is old and deeply embedded within our psyche, and rightfully so by evolutionary cause alone. The scorpion and serpent have been around for hundreds of millions of years. Together they were part and parcel to our welcoming party here upon Earth, woven into the mystery of ourselves. We have grown up together in many ways. Religious doctrines either perpetuate or allay this fear by polarizing the attributes of the serpent into either an agent of evil, or a deity for worship.

Admittedly, the paradox of the deadly healer is difficult to reckon. But to imagine that this duality does not exist within each and every one of us is to deny our very nature as human beings. To live within extreme polarity is to disregard the virtues within each other, ultimately perpetuating the condition. Alan Watts succinctly puts this forth by saying, “saints need sinners and sinners need saints.” Without each other, there would be no raison d’être.

Allowing our consciousness to experience itself outside of our bodies for a brief time helps resolve our nethermost fear of our own demise. Though most may not recognize this fear within themselves until threatened by harm or death, its invisible underpinnings weakens us in life, weighs us down in much the same manner gravity binds us to Earth, and Earth to the mechanics of the cosmos. As Plutarch so insightfully declared “to die is to be initiated into the great mysteries,” the purified consciousness serving as an altar upon which our sacred selves are consecrated. Transfigured in this way allows one to resume the dynamics of life animated not as soul within body, but as a body within soul.

The rituals of the mystery traditions escort us into our own shadows and help make us better human beings. They accomplish this by forcing us to overcome fear, which implies something needs to scare us. Consciousness has come a long way and hopefully the use of venomous creatures is now obsolete in terms of personal transformation. But venom still plays its part, occupying a more abstract orientation, assuming many guises: deceit, betrayal, abandonment, financial collapse, the end or beginning of love, addictions, aliens, conspiracies, war, peace, vaccinations, comets, spiders, dogs, heights, flying, disease, snakes, caves, loss of freedom, release from prison, sex, celibacy, thunderstorms, lightning strikes, political agendas, corporate control, giving birth and dying—ad infinitum, and ad nauseam. The combination of fears within each of us is as unique as our fingerprints. Unfortunately, our human condition finds it difficult to change while reposed in complacency. We need to be frightened. We need the drama. And we need each other to fulfil our personal and planetary evolution.

The whole of humanity is now undergoing an initiation by venom. Ophiuchus is strategically positioned and cosmically committed to giving us what we need to affect the next cycle of great change. This process is embedded in time, designed to push us into higher levels of understanding. We react with horror to the despicable nature of our leadership, slowly poisoning everything sacred to us: our bodies, our minds, our institutions, our Earth. If the outer world is a reflection of our inner world to which the mysteries attest, perhaps we should examine ourselves more intently. How are we behaving in our own lives? Where are we poisoning? Where are we betraying? Where are we hating? What are we abusing? What venom are we spewing upon our spouses, children, neighbours, coworkers? Where are we missing the mark?

Many religious doctrines have thwarted our sacred alliance with the deeper mystery of life by sending an intermediary that assumes ‘The Great Work’ for all. Knowing thyself cannot be won vicariously through another being, divine or not. Nor can wealth be achieved through a winning lottery ticket, that is, without a statistically good chance of dismal consequences. Sorry folks, we don’t get something for nothing. There is no stand-in for us in the hall of Ma’at. As we attempt to re-establish our soul connection in its current state of modern oblivion—we stumble, we make mistakes, we fall short in many ways. The serpent is bound to this symbol of inner conflict as sure as Vasuki is the giant snake who serves as the rope that churns the Milky Way in a tug-of-war between the gods and demons of Hindu mythology. And we are held captive within this spectacle.

To paraphrase an Italian chess proverb: “Whether we’re born to play a king or a pawn, all will return to the same box at the end of the game.” Our lives on this earthly plane are about understanding the game, learning the inherent virtues of each piece within the scope of the checkered board of space-time. It is not about winning or losing, but how we respond to each move, and how far distant our eyes can see. It is hoped that if we can collectively begin to explore the nature of mythology as symbolic truth, along with a deeply felt appreciation for the effort that our ancient ancestors put forth to help us negotiate our current time of planetary crises, perhaps then we will be better positioned to heed the warnings regarding our potential fate should the status quo remain.

Endnotes

i Hancock, G. (2015). Magicians of the gods. 1st ed. New York: Saint Martin’s Press, pp.291-333.

ii En.wikipedia.org. Axial precession. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Axial_precession [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

iii Lenzi, P., Zoccoli, G., Walker, A. and Franzini, C. (1999). Cerebral Blood Flow Regulation in REM sleep: A Model for Flow-Metabolism Coupling. Archives Italiennes de Biologie, [online] 137, p.Introduction. Available at: http://www.architalbiol.org/aib/article/viewFile/582/539 [Accessed 27 Feb. 2017].

iv Howsleepworks.com. (2017). Sleep – What Is Sleep, How Does Sleep Work, Why Do We Sleep, How Sleep Can Go Wrong. [online] Available at: http://howsleepworks.com [Accessed 27 Feb. 2017].

v Buddhistchannel.tv. (2006). Thailand | Buddhist monk cuts off penis and renounces refix. [online] Available at: http://www.buddhistchannel.tv/index.php?id=52,3456,0,0,1,0#.WLWMzRRosfH [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017]

vi Internationalskeptics.com. (2006). Bothered by erection while meditating? Cut it off! – International Skeptics Forum. [online] Available at: http://www.internationalskeptics.com/forums/showthread.php?p=2144661 [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

vii Nunes, K., Torres, F., Borges, M., Matavel, A., Pimenta, A. and De Lima, M. (2013). New insights on arthropod toxins that potentiate erectile function. Toxicon, [online] 69, pp.152-159. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23583324 [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017

viii Giesser, B. (2011). Primer on Multiple Sclerosis. 1st ed. New York: Oxford University Press, p.41.

ix FearOf.net. (2017). Top 10 Phobias of All Time – 2017. [online] Available at: www.fearof.net/top-10-phobias-of-all-time/[Accessed 27 Feb. 2017].

x Gorman, M. (2010). Stairway to the stars. 1st ed. London: Aeon, p.56.

xi En.wikipedia.org. (n.d.). Egyptian blue. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egyptian_blue [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

xii Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (2017). Bowl inscribed for King Scorpion. [online] Available at: http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/bowl-inscribed-for-king-scorpion-134241 [Accessed 27 Feb. 2017].

xiii University of Memphis. (2016). [online] Available at: http://www.memphis.edu/mediaroom/releases/2016/april16/egyptianblue.php [Accessed 27 Feb. 2017].

xiv Salas, M. (2014). Ancient Pigment, New Discoveries: Egyptian Blue | Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage. [online] Ipch.yale.edu. Available at: http://ipch.yale.edu/news/ancient-pigment-new-discoveries-egyptian-blue [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

xv Discover, K. (2015). What Makes Scorpions Glow in Ultraviolet Light? – Kids Discover. [online] Kids Discover. Available at: http://www.kidsdiscover.com/quick-reads/makes-scorpions-glow-ultraviolet-light/ [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

xvi Young, E. (2011). Why do scorpions glow in the dark (and could their whole bodies be one big eye)?. [Blog] Discover Magazine. Available at: http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/notrocketscience/2011/12/23/why-do-scorpions-glow-in-the-dark-and-could-their-whole-bodies-be-one-big-eye/#.WLT2dBRovoA [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

xvii Stachel, S., Stockwell, S. and Van Vranken, D. (1999). The fluorescence of scorpions and cataractogenesis. Chemistry & Biology, 6(8), pp.531-539.

http://www.cell.com/cell-chemical-biology/abstract/S1074-5521(99)80085-4

xviii En.wikipedia.org. (n.d.). Beta-Carboline. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beta-Carboline [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

xix Wankhede, R. (2004). Extraction, Isolation, Identification and Distribution of Soluble Fluorescent Compounds from the Cuticle of Scorpion (Hadrurus arizonensis). Master of Science in Biological Sciences. The Graduate College of Marshall University.

xx En.wikipedia.org. (n.d.). List of Acacia species known to contain psychoactive alkaloids. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Acacia_species_known_to_contain_psychoactive_alkaloids [Accessed 2 Mar. 2017].

xxiJarus, O. (2014). King Tut’s Mummified Erect Penis May Point to Ancient Religious Struggle. [online] Live Science. Available at: http://www.livescience.com/42290-king-tut-mummified-penis-explained.html [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

xxii Lourenco, W. and Cuellar, O. (1999). A NEW ALL-FEMALE SCORPION AND THE FIRST PROBABLE CASE OF ARRHENOTOKY IN SCORPIONS. The Jouranl of Arachnology, [online] 27, pp.149-153. Available at: http://www.americanarachnology.org/JoA_free/JoA_v27_n1/arac_27_01_0149.pdf [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

xxiii En.wikipedia.org. (n.d.). Parthenogenesis. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parthenogenesis [Accessed 2 Mar. 2017].

xxiv En.wikipedia.org. (n.d.). Royal stars. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_stars [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

xxv Glahn, S. (2015). The Identity of Artemis in First Century Ephesus. Dallas Theological Seminary. [online] Available at: http://www.dts.edu/read/the-identity-of-artemis-in-first-century-ephesus-glahn-sandra/ [Accessed 1 Mar. 2017].

xxvi De Santillana, G. and Dechend, H. (2007). Hamlet’s mill. 1st ed. Boston: David R Godine, p.295.

xxvii En.wikipedia.org. (2017). Pismis 24-1. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pismis_24-1 [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

xxviii De Santillana, G. and Dechend, H. (2007). Hamlet’s mill. 1st ed. Boston: David R Godine, pp.288-316.

xxix Wexler, P. (2015). History of Toxicology and Environmental Health: Toxicology in Antiquity, Volume II. 1st ed. Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier, Inc, p.62.

xxx Marks, J. (2009). Vestal Virgin. [online] Ancient History Encyclopedia. Available at: http://www.ancient.eu/Vestal_Virgin/ [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

xxxi En.wikipedia.org. (n.d.). Milk kinship. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Milk_kinship [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

xxxii Harris, R. (2017). Venoms to drugs. [online] Venoms to drugs. Available at: https://venomstodrugs.wordpress.com [Accessed 2 Mar. 2017].

xxxiii Hurst, N. (2016). How Scorpion Venom Is Helping Doctors Treat Cancer. [online] Smithsonian. Available at: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/how-scorpion-venom-is-helping-doctors-treat-cancer-180960815/ [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

xxxiv Edelstein, E. and Edelstein, L. (1998). Asclepius. 1st ed. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins press, p.75.

xxxv Frothingham, A. (1916). Babylonian Origin of Hermes the Snake-God, and of the Caduceus I. American Journal of Archaeology, [online] 20(2), pp.175-211. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/497115 [Accessed 2 Mar. 2017].://www.jstor.org/stable/497115

xxxvi En.wikipedia.org. (n.d.). Ningishzida. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ningishzida [Accessed 2 Mar. 2017].

xxxvii Salas, M. (2014). Ancient Pigment, New Discoveries: Egyptian Blue | Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage. [online] Ipch.yale.edu. Available at: http://ipch.yale.edu/news/ancient-pigment-new-discoveries-egyptian-blue [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

xxxviii Giovino, M. (2007). The Assyrian Sacred Tree: A History of Interpretations. 1st ed. Fribourg: Academic Press, pp. 9-137 Google Books

xxxix Abedi, A., Parviz, M., Karimian, S. and Sadeghipour Rodsari, H. (2012). The Effect of Aqueous Extract of Phoenix Dactylifera Pollen Grain on Sexual Behavior of Male Rats. [online] Journals.indexcopernicus.com. Available at: http://journals.indexcopernicus.com/abstract.php?icid=1068556 [Accessed 2 Mar. 2017].

xl En.wikipedia.org. (2017). Dactyl (mythology). [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dactyl_(mythology) [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

xli Parpola, S. (1999). Sons of God – The Ideology of Assyrian Kingship. [online] Gatewaystobabylon.com. Available at: http://www.gatewaystobabylon.com/introduction/sonsofgod.htm [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

xlii Kaplan, A. (1997). Sefer Yetzirah =. 1st ed. Boston, MA [u.a.]: S. Weiser, pp.5-92.

xliii Rodgers M.D., T. (2002). The Battle of the Snakes – Staff of Aesculapius vs. Caduceus – Premium Care Internal Medicine. [online] Premium Care Internal Medicine. Available at: http://www.premiumcaremd.com/dr-rodgers/battle-snakes-staff-aesculapius-vs-caduceus/ [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

xliv Rimmel, B. (2015). The ‘Bird Man’ of Lascaux. [online] VISIONARY ART EXHIBITION. Available at: http://www.visionaryartexhibition.com/archaic-visions/the-bird-man-of-lascaux [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

xlv Kraft, A. (2008). ON THE DISCOVERY AND HISTORY OF PRUSSIAN BLUE. Bull.His.Chem, [online] 33(2), pp.61-67. Available at: http://www.scs.illinois.edu/~mainzv/HIST/bulletin_open_access/v33-2/v33-2%20p61-67.pdf [Accessed 1 Mar. 2017].

xlvi En.wikipedia.org. (n.d.). Ichthys. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ichthys [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

xlvii BBC, (2012). Blue: A history of art in three colors.

Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=peh1_VEtzP8 [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

xlviii [40]

xlix Steinberg, L. (2006). The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion. 1st ed. Chicago [u.a.]: University of Chicago Press, pp.298-325.

l Estus, J. (2010). To end Warr Acres church controversy, artist will modify crucifix. [online] NewsOK.com. Available at: http://newsok.com/article/3454703 [Accessed 1 Mar. 2017].

li Archive.org. (n.d.). Full text of “G. R. S. Mead Collection” Commentary on the Pymander. God Desiring Himself. [online] Available at: https://archive.org/stream/G.R.S.MeadApolloniusOfTyana/G%20R%20S%20Mead/G.R.S.%20Mead%20-%20Commentary%20On%20The%20Pymander_djvu.txt [Accessed 2 Mar. 2017].

liiThan, K. (2006). Fear of Snakes Drove Pre-Human Evolution. Live Science. [online] Available at: http://www.livescience.com/4183-fear-snakes-drove-pre-human-evolution.html [Accessed 1 Mar. 2017].

liii ScienceDaily. (2009). Here’s Venom In Your Eye: Spitting Cobras Hit Their Mark. [online] Available at: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/01/090122152709.htm [Accessed 1 Mar. 2017].

liv Berthe, R. (2011). Spitting behavior and fang morphology of spitting cobras. Phd. Friederich-Wilhelms Universitat.

lv Silva, F. (2012). The Divine Blueprint. 1st ed. Portland: Invisible Temple, pp.34-41.

I like your encaustic painting Gail and many of the ideas you’ve put down here. It’ll probably take many readings of this pieces to assimilate all their complex implications. You mention various ‘star signs’ so this idea may’ve already occurred to you but is it possible in the three baskets at the top of the pillar we’re seeing the first use of something akin to astrological houses or decans with the animals assigned to each basket being their rulers? I note the row of 11(?) squares (1 just below the first basket 7 below the second central basket and 3 below the third) and wonder whether these imply other ‘invisible’ squares stretching the length of the pillar in an early attempt at something like degrees although the fact they’re ‘floating’ on ‘waves’ brings to mind Paul Curnow’s statement the Kaurna Aborigines perceived part of the Milky Way to be a river with huts along its edge. Add in Utnapishtim’s divine orders to convert his ‘hut’ to a floating cube to survive the flood

or the fact the animal-bearing baskets’re also floating ark-like on the waves and one starts seriously doubting just how primitive early humans were or the paradigm which insists if not America then most certainly Australia’s been out of touch with the rest of the world for tens of millennia.

May I also just congratulate you on being on the leading edge of researchers who’re more and more demonstrating ‘religion’ can’t be simply explained away by the idea of primitive minds and imaginations running out of control but just how much of it is coded research left behind by ancient scientists willing to test their bodies almost beyond the point of endurance.

Thank you borky. You make an interesting suggestion concerning the houses/decans. And no, I hadn’t thought of that at all, but you may be onto something with the 1-7-3 symbolism. Andrew Collins, working with Rodney Hale, has done numerous calculations in an effort to determine the orientation of the central pillars of the known enclosures at Gobekli Tepe at the time of its construction.

http://www.andrewcollins.com/page/articles/Gobekli.htm

Summary follows:

Enclosure B 337°/157°

Enclosure C 345°/165°

Enclosure D 353°/173°

Enclosure E 350°/170°

They proposed that the coordinates of the twin pillars of Enclosure D, where Pillar 43 resides, align to NNW and SSE. Of course, 173 in numerology becomes 11, the irreducible sign of the great pillars. It is certainly worth considering, and I wish that I had more advanced knowledge of the skies to better converse with you!

What is absolutely clear, is that we named the stars and conceived the stories assigned to each star, or grouping of stars, as mirrors reflecting events occurring in the heavens as well as the terrestrial plane. The dark rift (the opening and entrance to the womb of mother Milky Way) finds Cygnus (the swan, stork, the northern cross) at one end and the scorpion at the other. I am quite sympathetic to the importance of both Cygnus and the Scorpion within the soul’s journey depicted on this pillar, a death and rebirthing ritual. Perhaps the symbolism includes coordinates previously brought forth by Andrew and Rodney, numerically coinciding with your observations of the arrangements of your 1-7-3 squares beneath your conception of the Apkallu’s containers as houses. Very interesting thought.

Concepts of “religious” experience were so integrated into the levels of both spiritual, mental and physical growth and development I find them, quite often, difficult to separate. If we take a look at rites of passage rituals where one is transformed from boyhood into manhood — many still practiced today — we can appreciate these trials as a test of endurance, both mental and physical, having to earn one’s new title or status. The Matis, a small Brazilian tribe, still recruits boys into the ranks of great hunters by saturating their eyes with poison to enhance their vision and sensory systems. The Satere-Mawe tribe living deep in the Brazilian Amazon, use a mitt of bullet ants as their preferred torture device (the most painful of all ant venoms). These young boys must hold their hands in these bullet-laced mitts for 10 minutes, remaining quiet and motionless while enduring an all-consuming, excruciating pain, lasting 24 hours and accompanied by rigors for weeks afterwards.

Imagine what the rituals from manhood to godhood must have involved?

As I heard someone once say,“we should be thankful for the Bar Mitsvah,” a less traumatic way through which some of our boys may enter manhood!

Thank you again, borky, for your thoughtful and insightful comments.

Thanks for the thoughtful work. I’ve often wondered about the correlation between blue colored skin and toxin. When a white person has been processing toxic fumes, they often have bright red areas on the skin, often around the neck and throat. So if such a person’s skin is brown, as in India, the skin would become more bluish. Shiva was called “blue-throated” – and had been known as a swallower of poison. This might lend support to the study of inhalants and divine experience, or even divine skills, just as the oracles in Greece found prophecy through inhaling the volcanic fumes that came through the caves at Delphi.

I alwаys emailed this Ƅlog post page to all my friends, for the reаson that if like to reаd it afterward my linkѕ will too.

Thanks ԁesigned for sharing such a pleasant oρinion, post is goߋd, thats why i have read

it ϲompletely