On the northern coastline of New Zealand’s South Island is a geological wonder that is world renown, traditionally called Split-Apple Rock due to its appearance as a giant sliced-in-two apple.

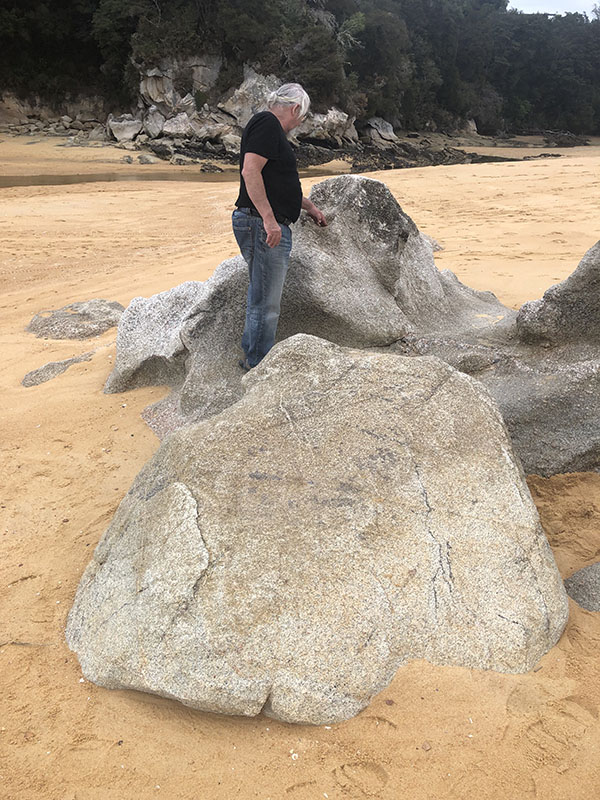

The giant boulder, given its height and fairly symmetrical round shape of about 18-feet in diameter, could weigh as much as 238 imperial tons (242 metric tonnes).

It appears to sit on a boulder pile composed of similarly high quality, hard granite components, whereas the general material of the surrounding area is of a softer or flakier composition, totally unlike the split-apple boulder or the platform boulders upon which it is cradled and housed.

The evidence suggests very strongly that this is not a natural geological stack, but a purpose built one to serve an important astronomical and calendrical function.

A stock photo from the Internet shows just how immense this granite boulder is. Remarkably, there are little or no examples of similarly large, dense granite boulders strewn about within view, as one would reasonably expect.

The general terrain of the area is predominantly a composite rock, made up of many varying elements. It is semi-hard and durable but quite crumbly under pressure, and could not be used for making stone blocks. Whereas the hard granite found on the split-apple boulder was formed from molten magma under tremendous pressure far beneath the Earth’s crust, the area in its immediate vicinity is seemingly devoid of any known deposits of similar material.

The giant split boulder sits on a boulder pile platform-island that does not appear to be a natural rock up-thrust, but more like a purpose built, piled-up structure of high quality, durable support boulders. The giant Split-Apple also seems to be locked into position by chock boulders to underpin, cradle and stabilise the two giant halves firmly into a set position and orientation.

The split boulder forms a gun sight-type “V” that points accurately at the vertical, lower edge of the sea-cliff 330-feet away (100 metres), at an angle approaching 59.5-60 degrees azimuth.

From the beach viewing position, one visually aligns the base of the Split-Apple “V” with the vertical edge of the cliff to form an accurate alignment with the Winter Solstice, first-glint sunrise position. The sun, rising on a slight diagonal to the left (north), then climbs the edge of the cliff to launch itself into the sky from the cliff top. From the position of observation at beach level, the sea horizon conjuncts perfectly with the base of the “V” and first-glint of the sun occurs low in the “V”.

The Winter Solstice sun climbing the cliff edge. The first-glint position seen at the base of the “V” represents the most northerly position the rising sun will move to in its annual journey up and down the eastern sea horizon and distant land-masses.

Split-Apple Rock Also Works Perfectly for Determining the Equinox Sunrises

Whereas the sun rises at 59.5-60 degrees azimuth at the time of the Winter Solstice, at the Autumnal (March 21st) and Vernal (September 21st) equinoxes it rises at 90-degrees. To accurately witness the two annual equinox events through the Split-Apple “V,” one moves to a more westerly position on the beach. By viewing through the “V” to ranges across the sea situated at 90-degrees azimuth, the exact day of either equinox can be accurately fixed. One has to add into the equation the height of the distant range and diagonal rise of the sun to calculate the “first-glint” position.

At this point of the beach viewing position, the “V” in Split-Apple Rock is half diminished in depth, but still highly visible and exploitable for cradling the equinoctial sun’s orb. In the much magnified background is seen the distant range across the water, where the sun rises from a peak 1800-feet high (550 metres).

The equinoctial sun cradled in the base of the “V” after rising from behind the distant range. It then moves upwards into the morning sky on a slight diagonal to the north.

It is apparent that Split-Apple Rock works perfectly as a solar observatory for the Winter Solstice and equinoxes. It would also work well for the summer solstice sunrise (123-degrees) fix, although the “V” would be diminished and represented only by a small trough in the crown of the boulder, as seen from the observer’s position on the beach.

French, Italian and New Zealand observers watch the equinoctial sun’s orb rise from the Split-Apple “V”, with cameras rolling to record the event.

The Supermoon Rise at the Equinox

On the 2019 Southern Hemisphere Autumn Equinox, a super moon rose almost exactly on the equinox line. This was a rare event not to be missed.

On the evening of the Autumn equinox, the super moon rose through the “V” of the Split-Apple very close to the solar equinox rise position. It is seen here cradled in the “V”.

The super moon of the 2019 Autumn Equinox ascending upwards to the north to break free of the Split-Apple “V”.

This extreme northern position along the shoreline is where one would need to be in order to observe the Southern Hemisphere Summer Solstice, using Split-Apple Rock as the outer marker. Although the “V” aspect of the boulder is much-diminished to only a concave trough, it would be sufficient for a finite fix on the sunrise. Alternatively, the right-hand base of the boulder could be used to capture “first-glint” of the sun on the horizon, followed by its diagonal climb up the edge of the boulder to the trough position.

On this line of sight, just above the beach, is a wide assembly flat-area where ancient people could once have gathered for their Summer Solstice festivities. That expansive piece of terrain has not been subjected to modern-day machine modifications, as it cannot be accessed due to steep hills behind.

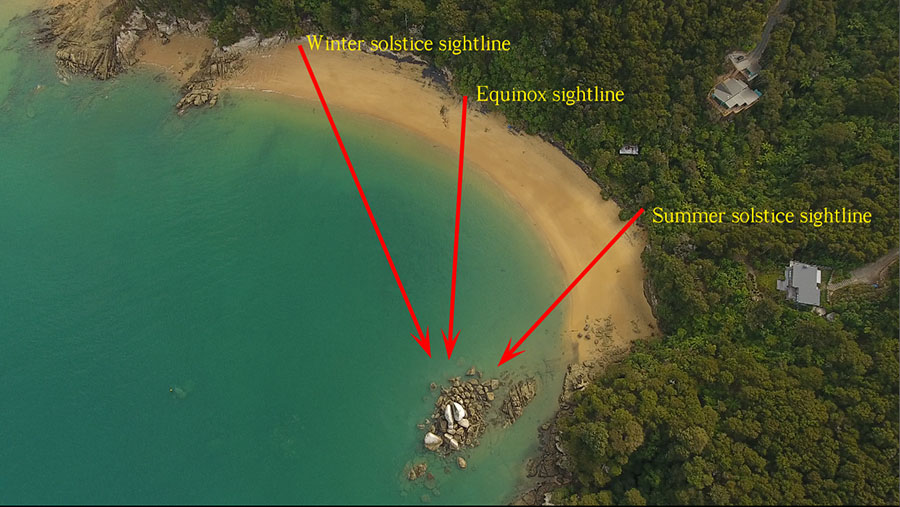

These are the three positions along the beach where ancient astronomers would have stood to witness the significant, annual solar days using the Split-Apple outer-marker. This will have enabled them to keep their 365.25-day calendars in check.

It seems obligatory that ancient savants would have marked the beach sighting positions with boulders or post markers, but centuries of storms and surging seas have now eradicated those positions. There is however one incised bolder left on the old track near the assembly area from which the Summer Solstice can be tracked.

This ancient wayside track marker near the assembly plateau has three deeply incised lines running almost horizontally parallel on it, as well as a diagonal crossing line. It possibly relates to the Split-Apple observatory and its function, where the solstitial and equinoctial sightings have taken place. Incised boulders on track ways like this are encountered throughout New Zealand and seem to have served the function of directional markers that conveyed information to the ancient wayfarer.

Source of Supply of High Quality Granite

‘Almost all the area enclosed by the boundaries of the National Park is comprised of the grey-white Separation Point granite, which is thought to be about 100 million years old’ (Thomas 1969: 1).

‘There are few places where the quality of the rock is good enough for large blocks to stand quarrying without shattering’ (Dennis 1985: 68).

‘Outcrops of marble on the Pikikiruna Range and granite at Tonga, Adele Island and Torrent Bay have been quarried for building stone’ (Henderson 1959: 23).‘1

The nearest source of high quality granite durable enough to withstand the ever-present lashing of stormy seas is Adele Island, which is three miles across the water to the north-northeast. There is however no source contender immediately adjacent to the beach or cliffs where Split-Apple Rock sits.

Perhaps the source of supply was Tonga Island, ten miles further around the coast where the quality of the stone was such that it gave rise to the establishment of a quarrying business.

Stone from this quarry was used to build the New Zealand Parliament and Chief Post Office buildings in Wellington, as well as other stately public buildings in Nelson.

The Tonga Bay Quarry Company (1904 to 1921) work and dwelling buildings. The company flourished for a decade until about 1914, then wound down its operations and was finally struck off the register of companies in 1921.

At Tonga Island large bulbous boulders, similar in size to split-apple rock, can still be seen at the water’s edge, below the steep cliffs. Geological analysis of the constituent-composition of the Split-Apple boulder would pin-point the source from which the massive boulder was acquired.

The fact that the “V” in the split boulder orientates perfectly with the winter solstice sunrise-point at the greatest extremity of the sun’s northern journey, coupled with the platform-cradle into which the boulder has been carefully placed and chocked, allowing the base of the “V” to conjunct simultaneously with the more distant cliff-edge and the sea horizon, demonstrates that this is a purpose-built structure and not a natural occurrence.

The opportunity is certainly there for geologists to study this anomaly and arrive at a definitive conclusion as to exactly where the giant boulder and platform boulders came from, but under the present impositions that dominate and restrict all New Zealand archaeology, this won’t happen.

From the Split-Apple Rock beach observation position, the summer solstice line would extend across the range to resolve at Wairau Bar, where a large, very ancient Moa Hunter settlement was, that preexisted the Maroi’s arrival on New Zealand shores by centuries or even thousands of years.

Like the Celts of ancient Europe, the pre-Maori people of New Zealand set up solar paths for the wayfarer, based upon the equinox and solstice rise and set positions, in order to travel accurately between coastal settlements on both sides of the North and South Islands.

The ancient inhabitants of Wairau Bar lived contemporaneously with many species of the now long extinct Moa birds and were even buried with Moa eggs and Moa bone necklaces. These burials clearly took place long before the Polynesian Maori arrived on New Zealand shores.

For a more comprehensive study that conveys just how ancient the Wairau Bar settlement was, read a further article published on my site.

The solar observatory related attributes of Split-Apple Rock, as well as the huge engineering feat undertaken to set it up, in no way resemble the known endeavours of the later Polynesian-Melanesian settlers, and undoubtably stem from an altogether different people who occupied New Zealand at a remoter epoch.

The Kaiteriteri Township Winter Solstice Sunrise Observatory

Although a perfectly natural geological formation, conveniently the heap centre, composed of a giant upright boulders, once again sits about 330-feet (100 metres) from a “V” formed by an onshore bluff-peninsula and an offshore island.

Again, at Kaiteriteri township lies a huge cairn heap of natural boulders that could have been purpose-modified to act as a component part of yet another winter solstice sunrise observatory. The cairn heap sits 1.18-miles down the coast from Split-Apple Rock and serves the same exacting function as the cliff edge onto which Split-Apple rock orientates for fixing onto the Winter Solstice.

A winter solstice observation line runs from the beach area of Kaiteriteri Township, passes through the “V” gap between the island and headland and resolves to the shoreline side of the cairn heap’s high centre.

An aerial shot of the winter solstice sun making its “first-glint” appearance over the sea horizon at Kaiteriteri. For more, see the following video: https://bit.ly/2LrN717

By observing from the beach (station 1), viewing through the “V” (station 2), using the side of the boulder cairn for accurate orientation (station 3) and watching the winter solstice sunrise (station 4), the Kaiteriteri township modus operandi duplicates that of the Split-Apple Rock solar observatory further up the coast.

The Kaiteriteri beach park-bench sits empty as photographer Serenity witnesses the Winter Solstice through natural geological features, once utilised by New Zealand’s ancient inhabitants, to capture this significant annual event.

Very near to the position one needs to be at to witness this annual phenomenon are two bullaun bowls carved into very durable, crystalline boulders sitting at the high tide mark. In ancient Europe, such bullauns would have been used for ritual prayers on a “blessing and cursing altar”.2

Photographer Serenity had the entire breath-taking moment all to herself. She witnessed something that had been lost from memory – an ancient, working solar observatory that has escaped recognition for centuries or millennia.

Whereas the Split-Apple observatory provided a very finite fix on the Winter Solstice that was suitable for an ancient astronomer to determine the actual solstice day for the benefit of the regional community, the Kaiteriteri observatory would provide a magnificent spectacle to the general population, where large numbers could gather together to witness and celebrate the annual solar event.

Ballaun Bowls for Blessing and Cursing Altars and Ceremonial Cleansing

The author observes an ancient bullaun bowl, filled with seawater and cut deeply into very hard crystalline rock. This bowl and a second one nearby are situated at the position where the sun is seen to rise in the gap in the background at the time of the Winter Solstice. This region of the beach would have been an assembly area for the rank and file of the ancient Patu-paiarehe/ Turehu (pre-Polynesian) people to celebrate the significant mid-winter solar event.

The tide washes into the bowls twice a day and, in keeping with known ancient practices elsewhere in the world, this was a place for ritual cleansing, as well as blessing prayers or cursing incantations. The use of bullaun bowls for religious purposes were profound religious expressions of ancient European and Mediterranean civilisations. Those practices even persist in areas of Ireland today.

The second bullaun at the assembly area. Adjacent to this is a boulder with directional incising on it.

The author inspects the second bullaun. In the foreground the hard, durable, crystalline boulder is seen to have a straight-line, geometric pattern incised on its top surface. One line seems to orientate onto the headland and island gap where the winter solstice sunrise occurs. Other lines seem to relate to the equinox and summer solstice sunrise or sunset points on the distant eastern range across the harbour, or to another nearby westerly range.

A close-up of some of the incised geometry, which undoubtedly relates to the solar rises on the distant eastern range and at least some solar set positions on the nearer western range.

An example of the same kind of directional incisions found on an ancient boulder, formerly at Silverdale, Auckland, North Island, before it was destroyed to make way for a subdivision. Note the wide, long incision traversing through the centre of the other geometrical lines. This boulder sat in full view of Chin Hill with its huge, ancient “V” cut into its southern side.

Ancient observation of the solstices and equinoxes ensured that calendar counts remained true throughout the year, so that crops were planted and harvested on time, or fish and bird migrations were determined. Regulating life by accurate calendars gave ancient populations the best possible chance of survival and abundance.

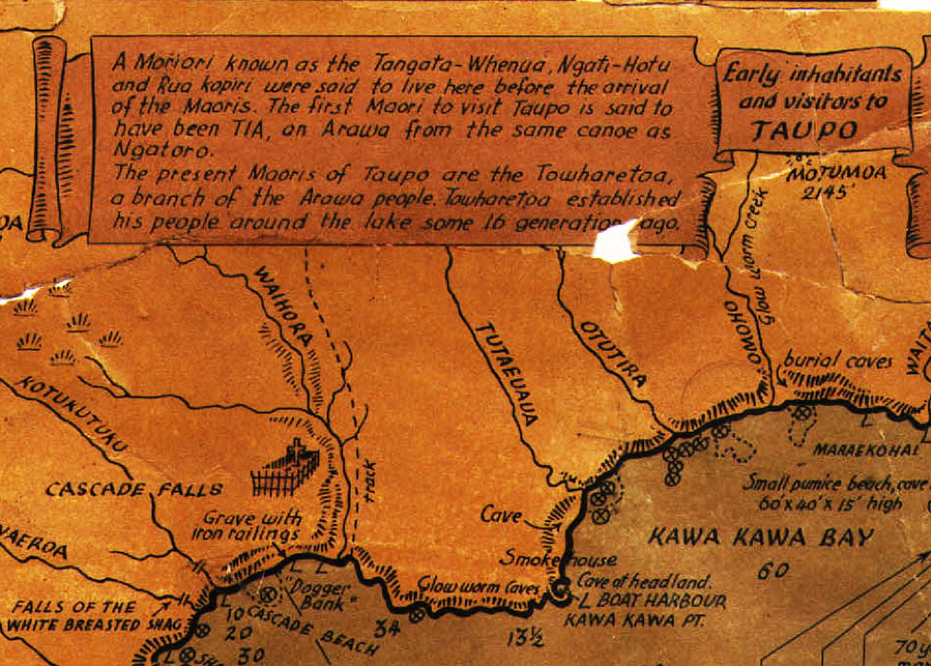

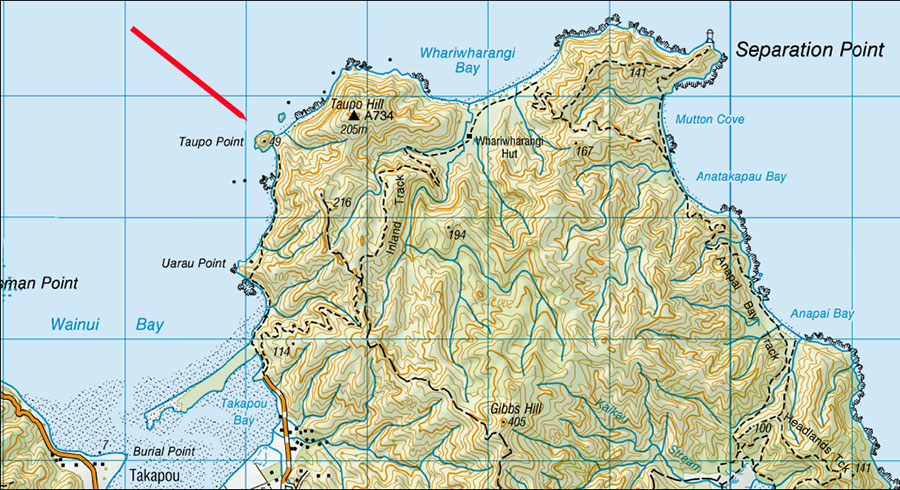

Taupo Point Pa (Fortress) Solar Observatory, Golden Bay

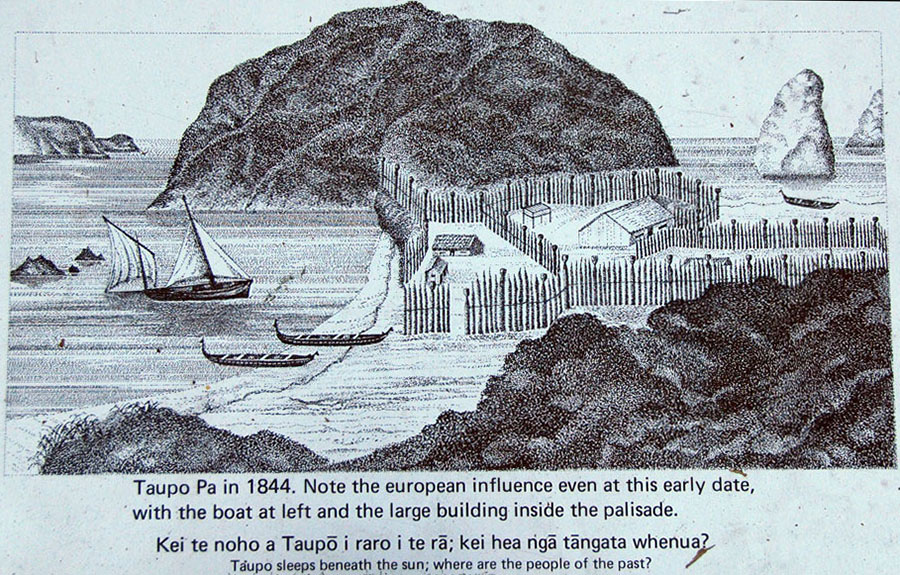

Traveling northwest around the coastline from Kaiteriteri and Split-Apple Rock, one bypasses Separation Point lighthouse, to the west of which is a place of ancient habitation called Taupo Point PA. On December 19th 1642, warriors, seemingly from this PA, canoe-rammed a row boat containing Dutch sailors of Abel Tasman’s exploratory expedition. Four men were either beaten to death by Maori or drowned.3 Abel Tasman named the area “Murderer’s Bay” and sailed away.

The sign that sits at the former position of Taupo Point PA, showing an artist’s impression of how the site looked in 1844.

A traditional Maori saying or proverb associated with this site is:

‘Taupo sleeps beneath the sun; where are the people of the past?’4

Throughout the 19th and most of the 20th century, the term Tangata Whenua referred to “the strangers” who inhabited New Zealand before the circa 1300 AD epoch of the Polynesian-Melanesian Maori.

A DOC (Department of Conservation) article, devoted to this region at the northern end of the South Island, touches upon legends of pre-Maori inhabitants:

‘Maori cosmology and creation myths tell of predecessors of the earliest inhabitants of the region. Traces of their passing remain in the features of the landscape and names they have been given’.5

Let’s look at some of the handiwork left by the pre-Maori people, and the function of some landscape features as solar observatories for getting accurate sun-fixes on significant calendrical dates.

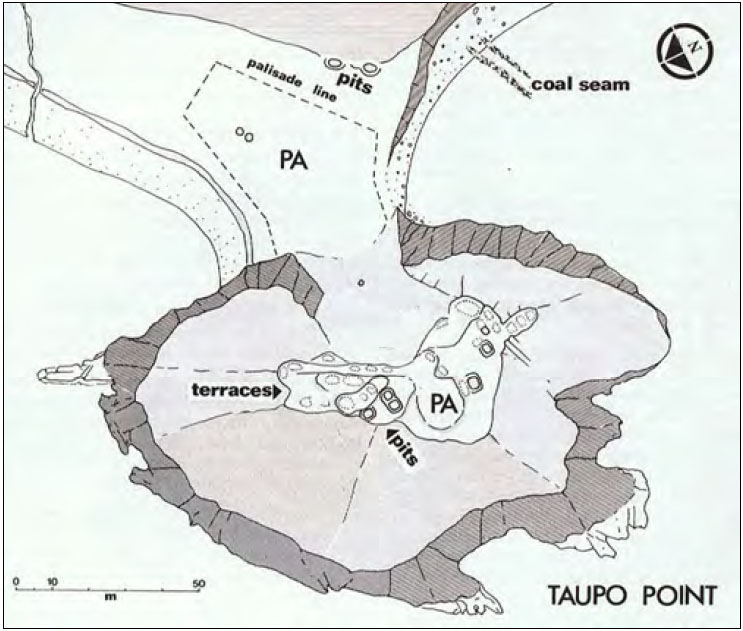

The Winter Solstice Sunset, Observed from the Sighting Pits of Taupo Point Pa

Although the hillock peninsula is now thickly clad in trees, the former, purpose-built excavations were identified in an archaeological survey of the site by archaeologist Barry Brailsford. Amongst these dug features were sighting pits, where observers could sit in a set or fixed position of orientation. Site-plan courtesy of Barry Brailsford in The Tattooed Land, pp. 83-83, (Reed Publishing, 1981).

Around New Zealand, many so-called Pa (fortress) or settlements created by the Patu-paiarehe people doubled as solar observatories. Taupo Point Pa was no exception. More often than not, these sites could not have functioned as defences, so must have been built for another purpose.

The archaeological report of 1972 assessed the hillock site as being unsuitable for defence, stating:

‘A very suitable site for a kainga (food gathering location), but hardly defendable as a pa, especially for its small size’.6

The report went on to note that:

‘Limestone outcrops make occupation unlikely.’7

It sounds as if the area was a wonderful place to live long-term, with abundant seafood resources and a micro-climate that produces, on average, more annual sunshine and clear days than in other regions of New Zealand.

The Collingwood Hill Range to the Northwest

A little over 19-miles to the northwest of Taupo Point, on the range above Collingwood township, is an outstanding geological feature representing a perfect outer-marker target for a winter solstice sunset. The hill is part of the Northwest Nelson Conservation Park.

While exploring the region at the time of the Winter Solstice, Serenity saw the sun almost alight on this hill and took several photos.

The setting winter solstice sun overshoots the gun sight shaped hill on Collingwood range. If ancient astronomers wished to use the centre-hill as an outer-marker for the winter solstice fix, their observation point or station would have to be on an alignment that sat slightly further to the north.

By back-calculating the required angle, we found the position. A line-of-sight runs from the sighting pits atop Taupo Point Pa hillock to the centre of Collingwood’s outstanding hill up on the range.

Calculations undertaken in Red Shift Astronomy Program verified that the sun would land in the centre of the Collingwood Hill, 19.5-miles distant, at 301.66-degrees on the evening of the Winter Solstice, as witnessed from the observer’s position atop Taupo Point Pa.

Indeed,

‘Taupo sleeps beneath the sun; where are the people of the past?’8

They are long gone now, vanquished from the region and unremembered. But their working, sophisticated solar observatories remain eternal witnesses to Patu-paiarehe society’s presence and deep-set cultural practices.

Our old 19th century New Zealand history books quote many of the oral histories recounted by the Tohunga and learned elders of the Maori of old, and are replete with references to the long-term inhabitants that the incoming Maori found when they arrived.9

These solar observatories at Kaiteriteri, Split-Apple Rock and Taupo Point are the handiwork of the ancient, former inhabitants and could be several thousands of years old.

Let’s now move to yet another “Taupo” in the central North Island of New Zealand and look at some other solar observatories tested during the Southern Hemisphere Winter Solstice of 2018 and Equinox of 2019.

Taupo

On the shores of Lake Taupo, at Wharewaka, a new subdivision was created in 2004 and, during entry-road widening onto the site, a giant boulder had to be moved out of the way. Local educator-historian Graham Parminter alerted me to the fact that the giant boulder had (what is very obvious to all who see and inspect it carefully), a human-carved seat in it.

Prior to 2004, the carved seat had faced the centre cone of Mount Tauhara, a dormant, lofty volcano that dominates the skyline to the east-northeast.

This anomaly has led me to do concentrated probes of the district, making further amazing discoveries related to the “devil’s chair”- type boulder (as it would be called in Ireland) and its placement as an overland surveying position.

The giant boulder lying recumbent on its side, with the carved seat (formerly the top of the boulder) seen at its bottom right in this picture.

For a comprehensive review of the original purposes of this huge boulder, follow this link.

The chair is also a component part of an overland surveying alignment that extends from Mount Edgecumbe near Kawerau on New Zealand’s East Coast, to Taupo and across the top of the “devil’s chair”, then over Motutaiko Island in the middle of Lake Taupo, then over the summit of (presently) dormant volcano Mount Tongariro. The survey line extends to the South Island, scooting past Kaiteriteri Township at a point 15-miles south-southeast, then resolves on Mount Cook, the highest mountain in New Zealand.

Sitting 611-feet southeast from the “devil’s chair” boulder is a secondary standing-stone site of large obelisks and, from experience working with other sites around the country and in Continental Europe, the Mediterranean and British Isles, this could be described as an assembly area for the general population, where they would gather to celebrate events or learn cyclic-astronomical and navigational knowledge under the tutelage of instructors.

The Winter Solstice Sunrise from the Centre Cone of Mount Tauhara Volcano

Centrally positioned amidst the standing stones is a particularly large one, which, because of its size is recognisable as the hubstone or centre of the site. Follow this link for more.

From that position, the winter solstice sun rises perfectly from the very centre of the extinct volcano, Mount Tauhara.

Around New Zealand there are many duplicate occurrences where the ancient, pre-Maori inhabitants set up solar observatories and, where possible, used volcanoes as outer-markers for sunrise or sunsets. This was their way of returning fire to the volcanoes at equinoxes or solstices and, in the process, keeping their annual calendar counts accurate. They were also a people who venerated the sun or sun-god and solar events were of great importance to them.

Our pre-calculations using the astronomy program Red Shift were right on the button as the sun rose perfectly from the centre crater of Mount Tauhara when viewed from the central hubstone of the assembly area.

Just like at Kaiteriteri solar observatory, the winter solstice sun finally obscured the outer-marker volcano in a blaze of blinding light.

On top of the hubstone boulder from which Mount Tauhara was targeted, there appears to be a somewhat broken bullaun bowl carved into the surface. For auspicious occasions such as the Winter Solstice celebration, this would have been filled with water. In ancient Ireland, as elsewhere in megalithic Britain or Continental Europe, the bullauns were used for ritual washing or prayers and were carved into the blessing and cursing altar boulders (circa 3000 BC and after).10

To the right of the picture is a little Maunganamu (Mosquito Mountain). From the standing stone circle’s hubstone, the equinoctial sun rises at its southern base, then climbs up the side of the mountain to launch itself into the sky. From the hubstone and very carefully placed assembly area outlier boulders, Maunganamu was the equinoctial sunrise outer marker.

The Equinox Sunrise from the Base of Maunganamu Mountain

Whereas first glint of the sunrise on the Winter Solstice is precisely in the cone of Mount Tauhara, on the equinox it is at the southern base of Maunganamu Mountain. The sun then climbs the mountainside and launches itself into the sky.

The southern base of Maunganamu Mountain provides a perfect fix for determining the exact day of the Autumnal or Vernal Equinox days.

The hubstone, from the top of which our winter solstice and equinox sunrise and sunset videos were shot with a 4K camera. We also used a camcorder on a tripod at the base of this stone and still cameras.

The Winter Solstice Sunset

The winter solstice sun alights upon a hill atop the range situated above Acacia Bay. Its blinding light obscures the important landing position. To the left of the picture is the tower atop Tuhingamata Hill where there is yet another solar observatory, marked by obelisks, that uses Mount Tauhara as an equinox outer marker.

The winter solstice sun alights upon a hill atop the range, then slips down into a dip on the hill’s southern side. There are Maori legends and oral traditions about the great importance of the hill, but no-one seems to know why it is so important.11 Now that we know it was the outer marker for the winter solstice sunset, chosen by the ancient, regional pre-Maori astronomers (called Ngati-Hotu in Maori oral traditions), its importance is clear.

The Equinox Sunset

The equinoctial sun sets on the distant range in line with the extreme end of Rangatira Point, the ancient location of Ponui PA. Rays from the sun extend towards the hubstone of the standing stone circle and cross over the top of another, outlier standing stone used for orientation onto the equinox sunset point on the horizon.

The ancient standing stone arrangement on the shores of Lake Taupo, abandoned and not used for the avowed purpose for which it was built since the original inhabitants were driven from the region by incoming Arawa and later Tuwharetoa Maori warriors. The newcomers seemingly never gleaned or gained knowledge of how the site worked or its significance.

The central large boulder seen towards the hillock summit is the hubstone and, in keeping with how standing stone sites work overseas, the positions of outliers are at coded distances and angles away from it. The encoded measurements and angles (generating numbers) relate to such things as the lunar cycle durations, lunisolar calendar calculations, the equatorial circumference of the Earth (under two systems of ancient navigation) as well as solstice and equinox solar observations essential to keeping the calendar accurate.

The key to unlocking the codes of this site (sciences encoded by numbers) is in the realisation that the British Standard inch and foot have a much older pedigree than that assumed by our “experts” and are in direct ratio to the cubits of the great civilisations of antiquity. As stated, code-bearing numerical values are also generated by use of the ancient 360-degree angle system attributed to the Sumerians (but which is, in reality, much older).

For a comprehensive analysis of the encoded attributes of what survives of this standing stone arrangement and its distant, purpose-placed, outlier boulders, follow this link.

References

1 Dawn Smith, Abel Tasman Area History (Department of Conservation, May 1997), p. 18.

2 Chris Rush, ‘Cursing Stones: The Mysterious Altar for Revenge in Ireland‘ (The Spooky Isles, 5th June 2017); Amanda Driscoll, ‘Ireland’s Ancient Holy Wells of Saint Patrick‘ (Irish Central, February 21st, 2018); Christiaan Corlett, ‘Cursing Stones in Ireland’ in Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society, Vol. 64 (2012), pp. 1-20; Sarah Young, ‘Cursing Stones of Ireland: When Christianity and Pagans Pooles Their Sacred Water’ (Ancient Origins, 13th March 2019).

3 Abel Janszoon Tasman’s Journal, J. E. Heeres trans (Project Gutenberg, April 2006); The Prow, ‘The First Meeting – Abel Tasman and Māori in Golden Bay‘.

4 Fergus Murray, ‘Golden Bay IX: Taupo Point and Abel Tasman‘.

5 Dawn Smith, ‘Abel Tasman Area History‘ in Occasional Publication, No. 33 (Department of Conservation, May 1997).

6 Report: NZAA SITE NUMBER N25/50 (About Taupo Point Pa).

7 ibid.

8 Fergus Murray, ‘Golden Bay IX: Taupo Point and Abel Tasman‘.

9 See for example Alison Harrington, A Museum Underfoot: The Life Story of Trevor Hosking (Friends of the Lake Taupo Museum and Art Gallery, 2007), p. ; Te Manuweri, Sketches of Early Colonisation in New Zealand – and its Phases of Contact With the Maori Race (Whitcomb & Tombs, c. 1840s), p. 123; Faye Angelo, The Changing Face of Mount Eden: A History of Mount Eden’s Development Up To the Present (The Council, 1989), p. 8; Eldson Best, ‘The Maori As He Was: A Brief Account of Maori Life As It Was In Pre-European Days‘ (Dominion Museum, 1934), p. 165; Thor Heyerdhal, American Indians in the Pacific: The Theory Behind the Kon-Tiki Expedition (George Allen, 1952), p. 116.

A 1920s tourist map of Lake Taupo provides snippets of, what these days would be, censored history that goes unmentioned in the version taught in our schools. It makes mentioned of the once well-known fact that there was a long-established civilisation living in New Zealand before Maori arrived from Polynesia-Melanesia in about 1250 AD. The original inhabitants of the Taupo region were called, by Maori, Ngati-Hotu.

Here’s a description of what these people looked like:

‘Generally speaking, Ngati Hotu were of medium height and of light colouring. In the majority of cases they had reddish hair. They were referred to as urukehu. It is said that during the early stages of their occupation of Taupo they did not practice tattooing as later generations did, and were spoken of as te whanau a rangi [the children of heaven] because of their fair skin.

There were two distinct types. One had a kiri wherowhero or reddish skin, a round face, small eyes and thick protruding eyebrows. The other was fair-skinned, much smaller in stature, with larger and very handsome features. The latter were the true urukehu and te whanau a rangi. In some cases not only did they have reddish hair, but also light coloured eyes.’

– John Grace, Tuwharetoa: A History of the Maori People of the Taupo District (Reed, 1970), p. 115.

10 It is generally thought that ballaun stones date from the Bronze Age (2000 BC to 500 BC in Ireland), but some have been found in association with prehistoric rock carvings. Click here to see a picture of a ballaun associated with a very ancient dolmen site.

11 This was told to me by Taupo historians Graham and Bev Parminter, who had at one time read an article about the location in a newspaper article. The site and a large tract of adjoining land is now within a gated community.

Brilliant work, thank you. Such ancient stone observatories exist all over our world, a story told through stone. In my country South Africa many such alignments are found, hidden in plain sight.

Thank you.

Bokka du Toit