“The discovery of cannabis residue on an ancient altar in Israel is presented with amazement by the archaeologists although one wonders where they have been for the last century. The kaneh-bosem of Exodus was identified as cannabis by Sula Benet nearly a century ago and has been the subject of numerous works since. Similar archaeological evidence is confirming the use of other drugs in Classical Greco-Roman and Judeo-Christian antiquity and is presented by scholars who apparently come upon their discoveries in vacuo.”

-Professor Carl Ruck on the archeological proof of cannabis in ancient Judaic ritual that was found in the temple site at Arad, Jerusalem

For more than a quarter century, I have been writing about a theorized role of cannabis in ancient Judaic temple worship, based on etymological and historical evidence. Cannabis Culture published one of my first articles on this in 1996, Kaneh Bosm: Cannabis in the Old Testament. Many disputed these claims, and rejected my work, others however embraced it, and word spread around enough on this, that the work took on a life of its own. Now the theory, has become a historical reality, through new archeological evidence.

The Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University, Volume 47, 2020 – Issue 1, published the paper Cannabis and Frankincense at the Judahite Shrine of Arad, by Eran Arie, Baruch Rosen & Dvory Namdar, wrote about the analysis of unidentified dark material preserved on the upper surfaces of two monoliths that were used in a jewish Temple site. The residues were submitted for analysis at two unrelated laboratories that used similar established extraction methods.

“On the smaller altar, residues of cannabinoids such as Δ9-teterahydrocannabinol (THC), cannabidiol (CBD) and cannabinol (CBN) were detected, along with an assortment of terpenes and terpenoids, suggesting that cannabis inflorescences had been burnt on it. Organic residues attributed to animal dung were also found, suggesting that the cannabis resin had been mixed with dung to enable mild heating. The larger altar contained an assemblage of indicative triterpenes such as boswellic acid and norursatriene, which derives from frankincense. The additional presence of animal fat―in related compounds such as testosterone, androstene and cholesterol―suggests that resin was mixed with it to facilitate evaporation. These well-preserved residues shed new light on the use of 8th century Arad altars and on incense offerings in Judah during the Iron Age.”

This research has led to International headlines, and is rocking the scientific and religious world with this astounding Revelation:

- Newsweek – Cannabis Discovered in Shrine From Biblical Israeli Kingdom May Have Been Used in Hallucinogenic Cult Rituals

- BBC – ‘Cannabis burned during worship’ by ancient Israelites – study

- Popular Archeology – New research reveals Cannabis and Frankincense at the Judahite Shrine of Biblical Arad

- The Times (UK) – Judean worshippers were high on cannabis, archaeologists reveal

- Haaretz – Ancient Israelites Used Cannabis as Temple Offering, Study Finds: Analysis of altar residue shows worshippers burned pot at a Judahite desert shrine – and may have done the same at the First Temple in Jerusalem

Countless other news sources have verified this study.

The Temple site at the centre of this controversial discovery, with the altars that tested positive for cannabis and frankincense.

‘Holy of Holies in the Israelite Sanctuary at Tel Arad’ by Ian Scott (CC BY-SA 2.0)

As the Newsweek article described:

“We can assume that the fragrance of the frankincense gave a special ambience to the cult in the shrine, while the cannabis burning brought at least some of the priests and worshippers to a religious state of consciousness, or ecstasy,” Arie said. “It is logical to assume that this was an important part of the ceremonies that took place in this shrine.”

“The new evidence from Arad show for the first time that the official cult of Judah—at least during the 8th century B.C.—involved hallucinogenic ingredients. We can assume that the religious altered state of consciousness in this shrine was an important part of the ceremonies that took place here,” he said.

Recently in April, Youtube as part of their censorship campaign, removed my 2014 Pot TV documentary ‘Kaneh Bosm: The Hidden Story of Cannabis‘, which had over 600 thousand views, for ‘false or dangerous’ information. Luckily others copied and shared it so it is still available.

The term kaneh bosm, is now being discussed by the team involved with the archeological discover, as a potential ancient Hebrew name for cannabis, as discussed in this Haaretz interview LISTEN: High Priests, Holy Smoke and Cannabis in the Temple

This excerpt from my most recent book, Liber 420, will give you some idea as to the context of this ancient Jewish use and how it became prohibited and lost:

Kaneh Bosm: Cannabis in the Bible?

“Prophets practiced ecstasy states and may have used incense and narcotics to produce impressive effects…. The Israelite prophets… acted as mediums. In a state of trance or frenzy they related their divine visions in a sing-song chant, at times a scream. These states could be induced by music… But the prophets also used, and sometimes abused, incense, narcotics and alcohol…” (Johnson, 1987) -Paul Johnson, A History of the Jews

The idea that the Old Testament prophets, may have been using psychoactive substances in order to attain a shamanic trance in which the revelations of Yahweh could be received, is as troubling for modern day believers, as Darwin’s theory of Evolution was to their 19th century counterparts, as just as Darwin’s theory of evolution challenged the myths of creation from the Books of Genesis, this entheogenic origin for the Jewish religion, indicates a scientifically and anthropologically based theory on the origins of the Bible itself through shamanism and psychoactive plants. As Professor Georg Luck has noted “The idea that Moses himself and the priests who succeeded him relied on ‘chemical aids’ in order to touch with the Lord must be disturbing or repugnant to many. It seems to degrade religion—any religion—when one associates it with shamanic practices…” (Luck, 1985/2006). Luck experienced these reactions himself, when his decades of research into magic rites in the ancient world, drew him to such a hypothesis. “As I was doing research on psychoactive substances used in magic and religion and magic in antiquity, I happened to come across chapter 30 in the Book of Exodus where Moses prescribes the composition of sacred incense and anointing oil. It occurred to me, judging from the ingredients, that… [these]substances might act as ‘entheogens,’ the incense more powerful than the oil. …” (Luck, 1985/2006)

Professor Luck pointed to the alleged mild psychoactive effects of myrrh and particularly Frankincense, as has been suggested by a number of recent studies, (Drahl, 2008; Khan, 2012). Frankincense contains Trahydrocannabinole, which is similar in molecular structure to Tetrahydrocannabinol the psychoactive component of cannabis. And it has been suggested that even in modern church rituals, the mild mood elevating effects of this may help to create a religious state of mind in parishioners close enough to inhale its effects. However, this alleged effect has been hard to reproduce in any notable way under clinic conditions. Luck noted this, explaining that “No two kinds of frankincense… have exactly the same effect. There are many varieties, coming from different regions along the ancient incense route, and some of the more potent ones may not be available any more. The blends used in churches today, seem rather mild, if they can be called psychoactive at all” (Luck, 1985/2006).

What Luck, and Johnson both seem to have been unaware of in their comments about the shamanic nature of the Israeli prophets and their potential use of psychoactive substances, is the evidence indicating a role for cannabis amongst the ancient Jews in this exact context.

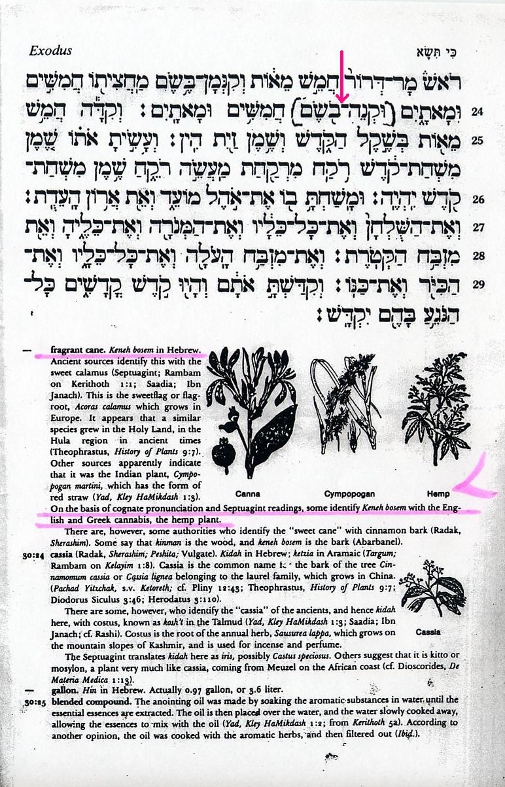

Although there have been a variety of suggestions regarding references to cannabis in scripture, which i have explored elsewhere, the most convincing evidence for cannabis in the Bible, comes via the Polish Anthropologist Sula Benet’s etymological investigations into the Hebrew word Kaneh Bosm. In her essays ‘Tracing One Word Through Different Languages’ (1936) and ‘Early Diffusions and Folk Uses of Hemp’ (1975), Benet demonstrated that the Hebrew terms ‘kaneh’ and ‘kaneh bosm’ (also translated ‘qaneh’, and ‘qaneh bosm’) identified cannabis, by tracing the modern term back through history, noting the similarities with the later Mishna term for cannabis, kanabos, as well as comparing it to the ancient Assyrian word kunubu (also translated qunubu) which has long been regarded as identifying cannabis, and which was used in an almost identical ritual context as kaneh bosm was by the ancient Jews. The root “kaneh” in this construction means “cane~reed” or “hemp”, while “bosm” means “aromatic”. This word appeared in Exodus 30:23, whereas in the Song of Songs 4:14, Isaiah 43:24, Jeremiah 6:20, Ezekiel 27:19 the term keneh (or q’aneh) is used without the adjunct bosem. As Sula genet has explained, the Hebrew word kaneh-bosm was later mistranslated as calamus, a common marsh plant with little monetary value that does not have the qualities or value ascribed to kaneh-bosm. This error occurred in the oldest of the Greek translation of the Hebrew texts, the Septuagint in the third century BC, and then repeated in following translations.

Considerable academic support has emerged for Benet’s theory on the identification of kaneh with cannabis. In 1980 the respected anthropologist Weston La Barre (1980) referred to the Biblical references in an essay on cannabis, concurring with Benet’s earlier hypothesis. In that same year respected British Journal New Scientist also ran a story that referred to the Hebrew Old Testament references: “Linguistic evidence indicates that in the original Hebrew and Aramaic texts of the Old Testament the ‘holy oil’ which God directed Moses to make (Exodus 30:23) was composed of myrrh, cinnamon, cannabis and cassia” (Malyon & Henman 1980). A modern counterpart of the word is even listed in Ben Yehudas Pocket Dictionary and other Hebrew source books. Further, online, the Internet’s informative Navigating the Bible, used by countless theological students, also refers to the Exodus 30:23 reference as possibly designating cannabis. This online text is largely based on the very popular The Living Torah, by Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan, a popular gift at bar mitzvahs, which correctly notes that “On the basis of cognate pronunciation and a Septuagint reading, some identify Keneh bosem with English and Greek cannabis, the hemp plant” (Kaplan, 1981). One can only speculate that before his death in 1983, Kaplan began to suspect that these connections went beyond linguistic theories, as in another work, published just prior to his death, Kaplan described later Jewish Kabbalistic writings that refer to the burning of certain grasses, which the learned rabbi stated “were possibly psychedelic drugs” (Kaplan, 1982).

A page from Rabbi Kaplan’s The Living Torah, referring to kaneh bosm, and listing cannabis as a candidate.

As well, William McKim noted in Drugs and Behaviour: an introduction to behavioral pharmacology, “It is likely that the Hebrews used cannabis… In the Old Testament (Exodus 30:23), God tells Moses to make a holy oil of ‘myrrh, sweet cinnamon, kaneh bosem and kassia’” (McKim, 1986). A Minister’s Handbook of Mental Disorders also records that “Some scholars believe that God’s command to Moses (Exodus 30:23) to make a holy oil included cannabis as one of the chosen ingredients” (Ciarrocchi, 1993). In the essay Psychoactive Agents and the Self, in The Lost Self: Pathologies of the Brain and Identity, (which deals with the biological basis of the human mind) Roy Mathews notes “The holy oil God instructed Moses to make… is believed to have contained cannabis. The previous translation of Kaneh Bosn as ‘calamus,’ a marsh plant, was found to be erroneous; the Hebrew Kaneh Bosn and Scythian cannabis were probably the same” (Mathews, 2005).

Numerous other researchers have also come to acknowledge that cannabis is in fact the most likely botanical candidate for the Hebrew keneh bosem. Most recently, author and Professor of Classical Mythology at Boston University, Carl Ruck,, who is also a linguist, has summarized:

“Cannabis is called kaneh bosem in Hebrew, which is now recognized as the Scythian word that Herodotus wrote as kannabis (or cannabis). The translators of the bible translate this usually as ‘fragrant cane,’ i.e., an aromatic grass. Once the word is correctly translated, the use of cannabis in the bible is clear. Large amounts of it were compounded into the ointment for the ordination of the priest. This ointment… was also used to fumigate the holy enclosed space. The ointment (absorbed through the skin) and the fragrance of the vessels (both absorbed by handling and inhaled as perfume) and the smoke of the incense in the confined space would have been a very effective means of administering the psychoactive properties of the plant. Since it was only the High Priest who entered the Tabernacle, it was an experience reserved for him…” (Ruck, 2009)

Noted cannabinoid researcher and historian, Dr. Ethan Russo, also notes: “I think it is absolutely clear that cannabis was in the Holy Land, we have archeological proof dated to the 4th century [AD] there was this carbonized fragment of cannabis that was found in a cave at Bet Shemesh in Israel. Additionally, I firmly believe that kaneh bosm in the Hebrew was cannabis, so I am absolutely convinced it was there. …its mentioned in Exodus that kaneh bosm was part of the Holy Anointing Oil, also used as an incense and it really makes sense.” (Russo, 2003) As Ruck and co-authors have noted the term “occurs also in Song of Songs 4.14, where it grows in an orchard of exotic fruits, herbs, and spices… It occurs also in Isaiah 43,24 where Yahweh lists amongst the slights received in sacrifice, the insufficient offerings of kaneh bosm; and Jeremiah 6,20, where Yahweh, displeased with his people, rejects such an offering; and Ezekiel 27.19, where it occurs in a catalogue of the luxurious items in the import trade of Tyre…. This conclusion has since been affirmed by other scholars. It is ironic that calamus “sweet flag,” the substitute for the alleged cannabis, is itself a known hallucinogen for which TMA-2 is derived” (Ruck et. al., 2001).

More recently other researchers have also written about cannabis as kaneh bosm, such as Christopher Lawson, Danny Nemu and Yoseph Needelman.

Kaneh bosm is connately similar sounding to the Assyrian name for cannabis, qunubu. And this connection is taken further by the identical use of qunubu incenses and ointments for spiritual purposes, to that of the Holy oil and Incenses of the Old Testament Jews and kaneh bosm.

Recipes for cannabis, qunubu, incense, regarded as copies of much older versions, were found in the cuneiform library of the legendary Assyrian king Assurbanipal (b. 685 – ca. 627 BC, reigned 669 – ca. 631 BC). Cannabis was not only sifted for incense like modern hashish, but the active properties were also extracted into oils. “Translating ‘Letters and Contracts, no.162’ (Keiser, 1921), qu-un-na-pu is noted among a list of spices (Scheil, 1921) (p. 13), and would be translated from French (EBR), ‘(qunnapu): oil of hemp; hashish’” (Russo, 2005). In Babylonian religious rites, “inspiration was derived by burning incense, which, if we follow evidence obtained elsewhere, induced a prophetic trance. The gods were also invoked by incense” (Mackenzie, 1915) Records from the time of Asurbanipal’s father Esarhaddon, cannabis, ‘qunubu’ as one of the main ingredients of the “sacred rites”. In a letter written in 680 bc to the mother of the Assyrian king, Esarhaddon, reference is made to qu-nu-bu. In response to Esarhaddon’s mother’s question as to “What is used in the sacred rites”, a high priest responded that “the main items…. for the rites are fine oil, water, honey, odorous plants (and) hemp [qunubu].” (Waterman, 1936) Cannabis was clearly an important ritual implement from early on in Mesopotamia. Professor George Hackman referred to 4000 year old inscriptions indicating cannabis in Temple Documents of the Third Dynasty of Ur From Umma, which described a “Memoranda of three regular offerings of hemp” (Hackman, 1937). Evidence indicates that in ancient Mesopotamia cannabis was also ingested in foods for ritual purposes as well as consumed in beverages, akin to the haoma/soma preparations as well, as rubbed on topically. (Bennett, 2010)

As the 19th century scholar Francois Lenormant noted in Le Magie chez les Chaldean: “The Chaldean Magus used artificial means, intoxicating drugs for instance, in order to attain to [a]state of excitement acts of purification and mysterious rituals increased the power of the incantations Among these mysterious rituals must be counted the use of enchanted potions which undoubtedly contained drugs that were medically effective” (Lenormant 1874).

An Assyrian medical tablet from the Louvre collection has been transliterated: “So that god of man and man should be in good rapport: —with hellebore, cannabis and lupine you will rub him.” (Russo 2005). Similar topical preparations containing cannabis, as shall be discussed later, occur in the 16th century Sepher Raziel: Liber Salomonis and other grimoires, and were also employed by later occultists Like L. A. Cahagnet, and P. B. Randolph along with others. Other cross cultural references to such topical preparations of cannabis have been identified (Bennett & McQueen, 2001; Bennett, 2006).

Health Canada has done scientific tests that show transdermal absorption of THC can take place. The skin is the biggest organ of the body, so of course considerably more cannabis is needed to be effective this way, much more than when ingested or smoked. The people who used the Holy oil literally drenched themselves in it. Based upon a 25mg/g oil Health Canada found skin penetration of THC (33%). “The high concentration of THC outside the skin encourages penetration, which is a function of the difference between outside and inside (where the concentration is essentially zero)” . Health Canada, who was concerned about people getting high off of hemp body products, concluded that, even with THC content limited to 10 ppm, “inadequate margins of safety exist between potential exposure and adverse effect levels for cannabinoids in cosmetics, food, and nutraceutical products made from industrial hemp.” (Health Canada, 2001) * I talked to Dr. Geiwitz personally at a conference shortly after this study was published and he told me that he felt this offered strong evidence for the potential psychoactive effects of the Holy Oil.

*as Cited in (James Geiwitz, Ph.D, 2001)

The Assyrian King Essarhaddon in a tent to capture incense smoke

(PD0)

Only those who had been “dedicated by the anointing oil of…God” (Leviticus 21:12) were permitted to act as priests. In the “holy” state produced by the anointing oil the priests were forbidden to leave the sanctuary precincts (Leviticus 21:12), and the above passage from Exodus, makes quite clear the sacredness of this ointment, the use of which the priests jealously guarded. These rules were likely made so that other tribal members would not find out the secret behind Moses and the priesthood’s new found shamanistic revelations. Or even worse, take it upon themselves to make a similar preparation. An event that would likely lead to Moses and his fellow Levites losing their authority over their ancient tribal counterparts. Those who broke this strong tribal taboo risked the penalty of being “cut off from their people”, a virtual death-sentence in the savage ancient world. Secrets revealed equals power lost, is a rule of thumb that is common to shamans and magicians worldwide, and the ancient Hebrew shamans guarded their secrets as fiercely as any. “The words spoken by the Lord to Moses… ‘where I shall meet with you,’ should be taken in the strictest literal sense. God will appear to the priest who uses the substance in the proper way. But the sanctions against any frivolous, casual use is formidable… By its nature, an ‘entheogen’ is surrounded by taboos, because it gives access to the deity, and the tremendous power it transmutes must be controlled.” (Luck, 1985/2006)

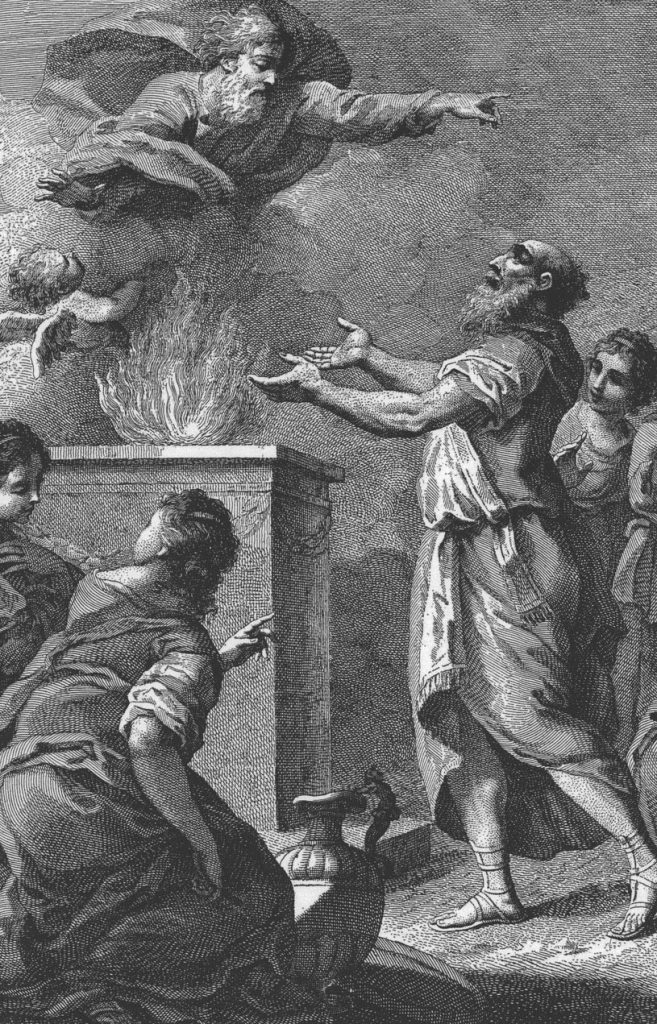

Moreover, this Holy Oil was to be used specifically in the Tent of the Meeting, where the angel of the Lord would “speak” to Moses from a pillar of smoke over the altar. From what can be understood by the descriptions in Exodus, Moses and later High Priests, would cover themselves with this ointment and also pour some on the altar of incense before burning it and during the ritual. “Besides its role in anointing, the holy oil of the Hebrews was burned as incense, and its use was reserved to the priestly class” (Russo, 2007).

Moses speaking to the angel of the Lord in a pillar of smoke over the altar

(PD0)

In the Torah, the pillar of smoke that arose before Moses in the ‘Tent of the Meeting’, is referred to as the ‘Shekinah’ and is identified as the physical evidence of the Lord’s presence. None of the other Hebrews in the Exodus account either see or hear the Lord, they only know that Moses is talking to the Lord when the smoke is pouring forth from the Tent of the Meeting. It is hard not to see all the classical elements of shamanism at play in this description of Moses’ encounter with God, and like Zoroaster, Moses can be seen as a ecstatic shamanic figure who used cannabis as a a means of seeking celestial advice. Such techniques of invocation certainly occur in later magic.

The Magician Moses scryed his messages from the Lord in an act of Biblical capnomancy, and this was a traditional use of cannabis in magical rituals that has been carried on in occult circles into modern times. As Ernest Bosc De Veze, who also wrote a Treatise on Hashish, noted in Petite Encyclopedie Synthetique des Sciences Occultes, in reference to “capnomancy… for divination… the smoke obtained from psychic plants such as verbena, hashish or Indian hemp… [are]used” (Bosc, 1904). In cases like this, not only was there the psychoactive effects of the smoke used, but the smoke provided the partially material basis in which the invoked entity or vision might be viewed. “The magician… burned aromatic substances and anointed his/her body with perfumed ointments. The whole set-up for an epiphany was there: now all that was necessary was for the deity to appear” (Brashear, 1991).

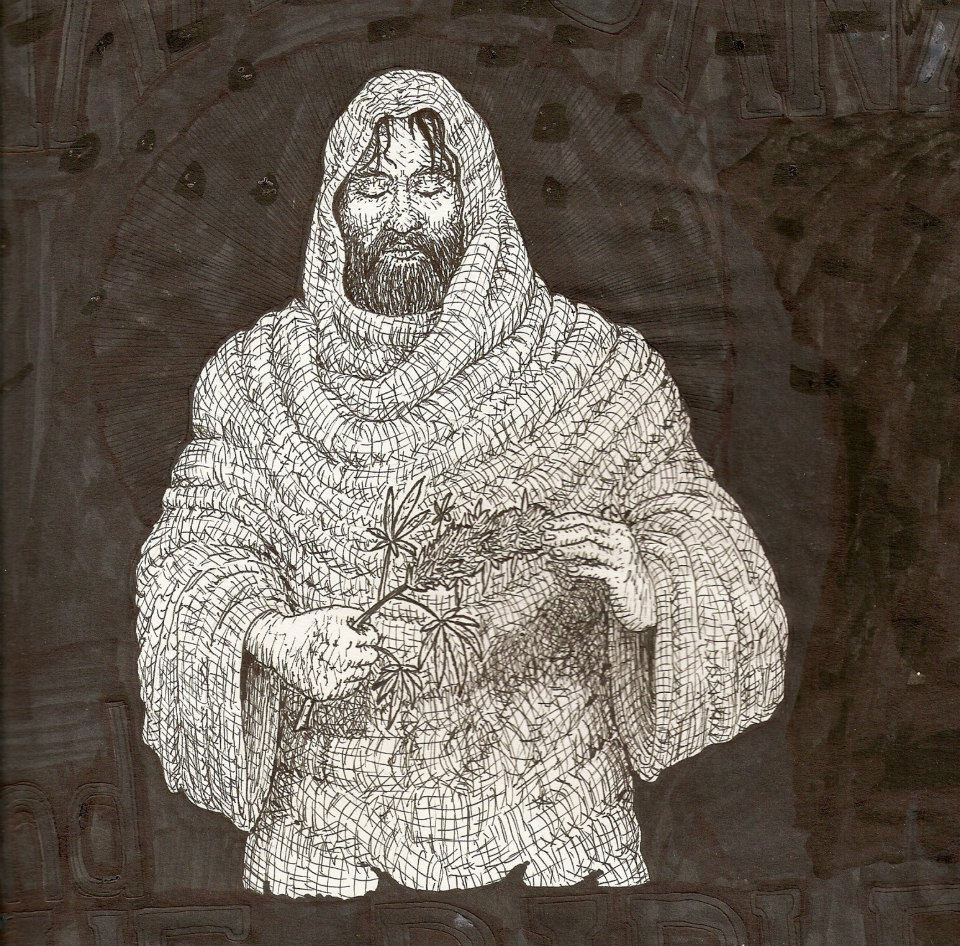

The High priest burning incense in the Holy of Holies

(PD0)

“…[T]he smoke itself was the epiphany. The smoke was inhaled by the magician and his client, and the vision came in trance. The smell of psychoactive substances… acts on the human brain in a very quick, very predictable way.”

“…[T]he inhalation of the sacred incense could create a powerful vision of the deity in the priest. Other factors were probably involved too, the smell of the holy oil with which the priest, the altar, and other sacred objects within the temple were anointed, the golden surface of the altar that reflected the shine of lamps…. The shiny surfaces, reflecting the sacral lamps nearby, could help induce trance in the priest as he was breathing smoke.” (Luck, 1985/2006)

Just as Moses received his answers in a billowing cloud of cannabis resin infused smoke, we can see from a reference in Isaiah, that when the cannabis was lacking, the scryed answers were more difficult to bring forth! the Lord complains he has been shortchanged his offering of cannabis. When the prophet seeks advice, the Lord complains:“Thou hast bought me no sweet [smelling]cane (kaneh) with money, neither hast thou filled me with the fat of thy sacrifices: but thou hast made me to serve with thy sins, thou hast wearied me with thine iniquities.”

Other textual evidence from Isaiah, although not identifying cannabis by name, gives clear indications that at times the Lord’s hunger for his favourite smoke was being appeased and hemp was being used as a shamanic incense inside the precincts of the temple, in elaborate shamanic ceremonies:

“And the posts of the door moved at the voice of him that cried, and the temple was filled with smoke.”

“Then said I, ‘Woe is me, for I am undone; because I am a man of unclean lips, and I dwell in the midst of a people of unclean lips; for mine eyes have seen the King, the Lord of hosts.’”

“Then flew one of the seraphims unto me, having a live coal in his hand, which he had taken with the tongs from off the altar, And he laid it upon my mouth and said, ‘Lo, this hath touched thy lips; and thine iniquity is taken away, and thy sin purged.’” (Isaiah 6:4-7)

Those of us who are familiar with hashish know that it burns in a similar way to both incense and coal and it’s not hard to imagine an elaborately dressed ancient shaman, with a mask and fabricated wings, lifting a burning coal of hashish, or pressed bud, to the lips of the ancient prophet Isaiah. Interestingly, the holder of the tongs is described as a “seraphim”, which translates as a “fiery-serpent”, and has been associated with the Nehushtan that Moses made and King Hezekiah later destroyed during his own religious reforms, because the Israelites were burning incense to it inside the temple itself.

Kaneh, (cannabis) can also be found in what is the most beautiful piece of prose in the whole Bible, Solomon’s Song of Songs’4.14, where it where it grows in an orchard of exotic fruits, herbs, and spices:

“Come with me from Lebanon, my bride, come with me from Lebanon… How much more pleasing is your love than wine, and the fragrance of your ointment than any spice!…The fragrance of your garments is like that of Lebanon…Your plants are an orchard of pomegranates with choice fruits, with henna and nard, nard and saffron, kaneh[cannabis]and cinnamon, with every kind of incense tree…” (Song of Songs 4:8-14)

Solomon has often been associated with magic, and this is particularly true of medieval European magical traditions where grimoires like, Clavicula Salomonis, ‘The Key of Solomon’ (14th-15th century) and the 17th-century Clavicula Salomonis Regis, ‘The Lesser Key of Solomon’ both of which represents a typical example of Renaissance magic. Most interesting of such magical manuscripts, is the 16th century Sepher Raziel:Liber Salomonis, which has been discussed for its use of cannabis ointments for seeing visions in magic mirrors.

However, Solomon’s reputation for magic, goes back much further than this. The Testament of Solomon, thought to date from sometime between the first and third century AD, is one of the oldest magical texts concerning the ancient Jewish king. This text is pseudepigraphic catalog of demons summoned by King Solomon, and how they can be countered by invoking angels and other magical techniques. The Testament of Solomon refers to a story where the magician-king forces a demon to spin hemp! “So I commanded her to spin the hemp for the ropes used in the building of the house of God; and accordingly, when I had sealed and bound her, she was so overcome and brought to naught as to stand night and day spinning the hemp” (The Testament of Solomon, 100-300 AD)

Ingested cannabis references have also been long suggested, such as that in a 1903 essay, Indications of the Hachish-Vice in the Old Testament, Dr. Creighton, referred to accounts in the books of Daniel, Samuel, and particularly Ezekiel in this regard. “‘Son of man, eat what is before you, eat this scroll; then go and speak to the house of Israel.’ So I opened my mouth and he gave me the scroll to eat….So I ate it, and it tasted as sweet as honey in my mouth….Then the Spirit lifted me up, and I heard behind me a loud rumbling sound–May the glory of the Lord be praised in his dwelling-place!–the sound of the wings of the living creatures brushing against each other and the sound of the wheels beside them, a loud rumbling sound. The Spirit then lifted me up and took me away…” (Ezekiel 3:4-14).

Others have suggested that the Important Biblical and Apocrypha figure Ezra, consumed a cannabis infused wine. Ezra was a key figure of the Jewish monotheistic reformation after the Persians had returned them to their homeland. Interestingly, at least two researchers, living more than a century apart and from different parts of the world, have concluded that Ezra received his inspiration for this act, from the same source of inspiration as his Zoroastrian overlords did….. a cannabis infused wine! Here is Ezra’s own account of this. Ezra told the people not to seek him for forty days, and he left for the desert, taking with him five people who were to act as his scribes:

“The next day, behold a voice cried to me saying. Esdras open thy mouth, and drink what I give you thee to drink! Then opened I my mouth, and behold, he reached me a full cup, which is full as it were with water, but the color of it was like fire. I took it, and drank: and when I had drunk of it, my heart uttered understanding, and wisdom grew in my breast, for my spirit strengthened and my memory; and my mouth was opened and shut no more: and they sat forty days, and they wrote in the day, and at night they ate bread. As for me, I spake by the day, and I held not my tongue by the night. In forty days they wrote two hundred and four books” 2 Esdras 14:38 to 44.

As Georg W Brown recorded of this more than a century ago:

“A voice bid him open his mouth, he—the voice, of course—reached Esdras a full cup. It would be interesting to know whose voice it was which possessed such unnatural powers; yet we apprehend the reader is much more anxious to know the contents of the cup… which possessed such wondrous ability, probably the same possessed by the ‘fruit of the tree’ which grew ‘in the midst of the garden,’ the eating of which opened the eyes of our first parents, and enabled them to see ‘as Gods knowing good and evil.’ We think we can furnish this desired information, to do which we are compelled to anticipate some facts existing among Zoroastrian worshippers; many centuries before the date religionists ascribe to Abraham, and which was practiced in Persia, Assyria and Babylonia at the very time Ezra was writing Jewish history under the influence of the ‘fiery cup.’

“Among other duties required on occasional sacrifices of animals to Ahura-Mazda, additional to prayers, praises, thanksgiving, and the recitation of hymns, was the performance…of a curious ceremony known as that of the Haoma or Homa. This consisted of the extraction of the juice of the Homa plant by the priests during the recitation of prayers, the formal presentation of the liquid extracted to the sacrificial fire,… the consumption of a small portion of it by one of the officiating ministers, and the division of the remainder among the worshippers…”

“What was the Haoma or Homa, the production of the moon-plant, growing in those regions of Asia to far north for the successful growing of the grape, and yet yielding such intoxicating properties? It is known in the medical books as Apocynum Cannabinum, and belongs to the Indian Hemp family, Cannabis Indica being an official preparation from it. It is now known in India as bhang, and is popularly known with us as hashish, the stimulating and intoxicating effects of which are well known to physicians.” (Brown, 1890)

More than a century after Brown, Vicente Dobroruka also noted a comparison between the Persian technique of shamanic ecstasy and that of Ezra the article, in his essay Preparation for Visions in Second Temple Jewish Apocalyptic Literature: “Similar drinks appear in Persian literature…Vishtapa has an experience quite equivalent in the Dinkard … where mention is made to a mixture of wine (or haoma) and hemp with henbane… The Book of Artay Viraz also mentions visions obtained from wine mixed with hemp, and for the preparations of the seer…”(Dobroruka, 2002)

Dobroruka revisited this theme in more detail in his later 2006 article, Chemically-induced visions in the Fourth Book of Ezra in light of comparative Persian material, and again draws direct comparisons between Ezra’s cup of fire, and the mang mixed infused beverages of the Zoroastrian psychonauts. Interestingly, Rabbi Immanuel Löw, referred to a ancient Jewish recipe (Sabb. 14. 3 ed. Urbach, 9th-11th century) that called for wine to be mixed with ground up saffron, Arabic gum and hasisat surur, “I know ‘surur’ solely as a alias for the resin the Cannabis sativa” (Low, 1924).

Low made no comment on the word “hasisat” which is very reminiscent of the name for cannabis resins in the medieval Arabic world “hasis” (hashish), and the term is generally thought to have been derived at in that period. However, the 19th century scholar John Kitto also put forth two different potential Hebrew word candidates for the origins of the term “hashish” in A Cyclopaedia of Biblical Literature. Kitto pointed to the Hebrew terms Shesh, which originates in reference to some sort of “fibre plant”, and the possibly related word, Eshishah (E-shesh-ah?) which holds a wide variety of somewhat contradictory translations such as “flagon” “sweet cakes”, “syrup”, and also “unguent.” This last reference is interesting in relation to what we have already seen in regards to the cannabis infused Holy Oil, which was basically an unguent. According to Kitto, this Eshishah was mixed with wine. “Hebrew eshishah… is by others called hashish…. this substance, in course of time, was converted into a medium of intoxication by means of drugs” (Kitto 1845:1856). With the cognate pronunciation similarities found between the Hebrew Shesh and Eshishah one can only speculate on the possibility of two ancient Hebrew references to one plant that held both fibrous and intoxicating properties. It seems likely that what is referred to is hashish resin, with the addition of the word “surur” indicating the possibility of hashish oil, (which the Arabs prepared by boiling the tops of the plant, and collecting the drops of oil that formed on top of the water). A very potent preparation. “The palm wine of the East… is made intoxicating… by an admixture of stupefying ingredients, of which there was an abundance… Such a practice seems to have existed amongst the ancient Jews…” (Kitto, 1861)

Talmudic reference indicates this use as well: “The one on his way to execution was given a piece of incense in a cup of wine, to help him fall asleep” (Sanh. 43a). Such preparations were used by the ancient Jews, for ritual intoxication, and for easing pain. A Reverend E. A Lawrence, in an essay on ‘The wine of the Bible’ in a 19th century edition of The Princeton Review noted that:

“It appears to have been an ancient custom to give medicated or drugged wine to criminals condemned to death, to blunt their senses, and so lessen the pains of execution. To this custom there is supposed to be an allusion, Prov. xxxi. 6, ‘Give strong drink unto him that is ready to perish,’ …To the same custom some suppose there is a reference in Amos 8, where the ‘wine of the condemned’ is spoken of… The wicked here described, in addition to other evil practices, imposed unjust fines upon the innocent, and spent the money thus unjustly obtained upon wine, which they quaffed in the house of their gods…”

“Mixed wine is often spoken of in Scripture. This was of different kinds… sometimes, by lovers of strong drink, with spices of various kinds, to give it a richer flavor and greater potency (ls. v. 22; Ps. lxxv. 8). The royal wine,’ literally wine of the kingdom… Esther i. 7), denotes most probably the best wine, such as the king of Persia himself was accustomed to drink.” (Lawrence, 1871)

Thus, this infused wine, not only had pain numbing qualities, but was also “quaffed in the house of their gods” giving clear indication it was sought after for entheogenic effects as well. That it is compared to the wines of the Kind of persia, also brings us back to the cannabis infused wines of the Zoroastrian period, such as that taken by King Vishtaspa. In reference to “unguents” such as the Holy oil, placing “incense” into wine, we are reminded of the cannabis infused incenses and anointing oils referred to earlier, indicating these substances may have come to have been placed directly into wine. In regards to myrrhed wine, it is worth noting that Dr. David Hillman, who holds combined degrees in Classics and Bacteriology, has suggested that ancient myrrh was often doctored with cannabis resins “The [ancient]Arabs… will take the rub, basically the hashish… they adulterate it with myrrh, so you end up with these combinations of plants that actually end up together… myrrh and cannabis, you see them associated… often” (Hillman, 2015).

Now what is the world going to say when they find out that some centuries after this ancient Jewish use, it would appear that Christians were using cannabis for its miraculous healing properties, as well as in entheogenic initiation rituals? Jesus took the restricted use of cannabis from the Priests and kings, and brought it to the people. Jesus was a Cannabis Activist.

Chris Bennett has been researching the historical role of cannabis in the spiritual life of humanity for more than a quarter of a century. He is co-author of Green Gold the Tree of Life: Marijuana in Magic and Religion (1995); Sex, Drugs, Violence and the Bible (2001); and author of Cannabis and the Soma Solution (2010); and Liber 420: Cannabis, Magickal herbs and the Occult (2018) . He has also contributed chapters on the the historical role of cannabis in spiritual practices in books such as The Pot Book(2010), Entheogens and the Development of Culture (2013), Seeking the Sacred with Psychoactive Substances (2014), One Toke Closer to God (2017), Cannabis and Spirituality (2016) and Psychedelics Reimagined (1999). Bennett’s research has received international attention from the BBC , Guardian, Sunday Times, Washington Post, Vice and other media sources. He currently resides in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Excellent article! Wow! I hope we can all learn to work with Cannabis and receive her gifts!! It’s time for the rest of the world to know the truth!! Cannabis is for the healing of the Nations! It’s time! ♥️

This is very well researched and clearly summarised article, biut it accepts some of the main faults of the archaeologists or scientists (mainstream in some) whereby they make unjustified (even if possibly true, but not always, but logically faulty, jumps in their reasoning: ‘Skin is the biggest organ, so it needs a lot more cannabis to absorb this way’ – er, no, you could put more on, but it penetrates well, you do not need to, however, absorpttion through skin IS slow, AND maintained; ‘cannabis burning on an altar at the entrance to a shrine (roofless in the picture) produced smoke in an enclosed space – er, no, not if it outside the door of a roofless space; ‘cannabis was mixed with animal dung on the altar by jewish priests’ – but how do we know it did not get there separately when the temple was desecrated and burned by dung-flinging invaders; ‘all mentions of cane in the ancient texts refer to modern cannabis’ – no, I think there is enough unequivocal evidence that there were a large variety of fragrant canes, which were possibly used interchangeably (though the biblical references might indicate with sometimes inadequate results!)in different parts of the world; ‘all hemp is intoxicating and nothing else’ – do all varieties of hemp grown at all lattitudes produce only cannabis oils? Or were they grown in some places solely for the rope-fibre, because the climate affected what could be grown and what it contained? I just think that scientists, and archaologists in particular, often make unjustified assumptions, failing to consider all possibilities, and that can be said on both sides of the argument: this article makes a very strong argument, but it is weakened slightly by some asumptions repeated ‘from the camel mouth’ without challenge, and because the central theme focusses too narrowly on proving that modern cannabis, to the exclusion of the other ‘fragrant canes’ which also produced psychedelic substances, was the only ingredient in the biblical intoxicant.

animal dung was a common fuel, and is referred to as such in the Bible. Chemical analysis of the cannabis residue from the altars was done, this was not ‘hemp’, but a quality cannabis extract of sorts.

The shrine is roofless in the picture, as that is the rock work that survived, the tent of the meeting in the Holy of Holies, on which this altar at Arad was based, is clearly described. Tents do not survive like rocks. I don’t see a single reasonable challenge to what appears in the article in what you wrote, but rather your unfamiliarity with the territory, and not following the references and links provided in this piece as follow up before commenting.

Thank you so much for this information!

I am a cannabis user and I lead ceremonies using this medicine and sound healing.

I have been connecting to the energy of it mostly through the native and south american traditions where they refer to cannabis as Santa Maria. It is so nice to hear that there is this history in my jewish roots as well!! Thank you so much!!