Visionary art is the most direct continuation of the oldest known representational art in the world.

For my upcoming book Visionary Art, I researched the oldest known artworks to inquire into the origins of human creativity. Here, I will share with you my discoveries: both an awed exploration of these earliest milieus of art-making highlighting up-to-date research, as well as an argument for the interwoven matrix between archaic art, psychedelic and altered states, and the visionary art of today.

The courageous and dedicated research of David Lewis-Williams, Jean Clottes, and Graham Hancock offers powerful insights into these oldest of images. As we will see, an open-minded and nuanced investigation of archaic art, informed by the sciences that illuminate them, discerns specific qualities that reverberate in visionary art throughout the ages and unearths resources in human consciousness essential to facing the global challenges of our time.

Paleolithic Art and The Deep Past

Oldest known drawing to date, found in Blombos Cave c. 73,000 years BP. Public domain, Henshilwood, C.S. et al., Wikimedia Commons.

Evidence found in Morocco has shown that anatomically modern humans have existed for at least 315 thousand years. Few traces of “art” have been found from the first 215 thousand years or so, eons of human existence faded by the expansive mists of time. One point of illumination comes from South Africa, where artifacts from Blombos Cave (on the coast near Cape Town) show some of the earliest known traces of creative expression. The oldest discovered “drawing” was found here of geometric marks in red ochre on a rock dated to 73,000 years BP (before present). A rock with criss-cross engravings and drilled shell beads have been dated to 77,000 years BP, with other evidence of human activity in the cave extending further back to roughly 100,000 years ago.

For tens of thousands of years, culture and creative expression seem to have endured at a comparable level — a few vague marks and beads here, hammerstones and flaked blades there. Surely, much of the richness of these eras is lost to time, and their subtle developments continue to be studied in light of ongoing research and new discoveries.

Decorated Caves

Yet a growing abundance of evidence from roughly 30–51,000 years ago reveals the presence of spectacular creative achievements that may point to a broad development forward — an emergence of artistic expression as yet unanticipated by evidence from earlier ages. The oldest known representational images made by humans first appear in this timeframe on cave walls, known as parietal art (or, more generally, cave art or rock art). They are scattered throughout two distinct regions: Indonesia (Sulawesi and Borneo), beginning at roughly 44–51,000 years ago, and then millennia later in Europe, beginning at roughly 31–40,000 years ago, mostly in France and Spain, but also found as far east as the Ural Mountains in Russia. These two separate milieus thousands of miles apart share specific and striking similarities, as we will see, that conjure enigmas of profound depth and invite compelling conclusions. Scientific investigation suggests these artistic developments evolved in concert with archaic technology, communication, and culture. An “open question” remains as to whether the similarities between Indonesia and Europe point to an earlier development in Africa from which both cultures ultimately evolved or whether they developed independently. Discoveries of many of these oldest known parietal works are very recent, especially those in Sulawesi in the past ten years, making our collective vision today suddenly reawakened to their awesome implications.

45,500 year old cave art in Tedongnge, Sulawesi, Indonesia. Photo by Basran Burhan (CCBYSA4.0)

The images inside the caves of both Indonesia and Europe share several specific features. Most dramatically, they show beautiful representations of fauna local to the region. In Sulawesi, there are multiple instances of warty pigs and small buffalo (“anoas”) rendered in red ochres. The oldest known example of any representational art to date is a warty pig at Sulawesi’s Leang Karampuang (“Sacred Cave” in Indonesian), dated to at least 51,200 years BP. The more famous European images, such as those in Chauvet Cave (France, dated 31–36,000 years BP), show now-extinct species, including bison, horses, lions, cave bears, aurochs, mammoths, woolly rhinos, and deer often deep inside treacherous cavern systems. In both regions, the earliest animals already show what we recognize as superb artistic skill. They are almost always shown in profile view and seem to float in spaces without any clear delineation of landscape or ground beneath them, and plants are almost completely absent. Hand stencils in which paint may have been sprayed from tubes are commonly found, as well as much rarer “positive” handprints in which paint was directly applied from hand to cave surface.

Hand stencils in Pettakere Cave (Sulawesi) c. 39,000 years BP. Photo by Cahyo Ramadhani (CCBYSA4.0)

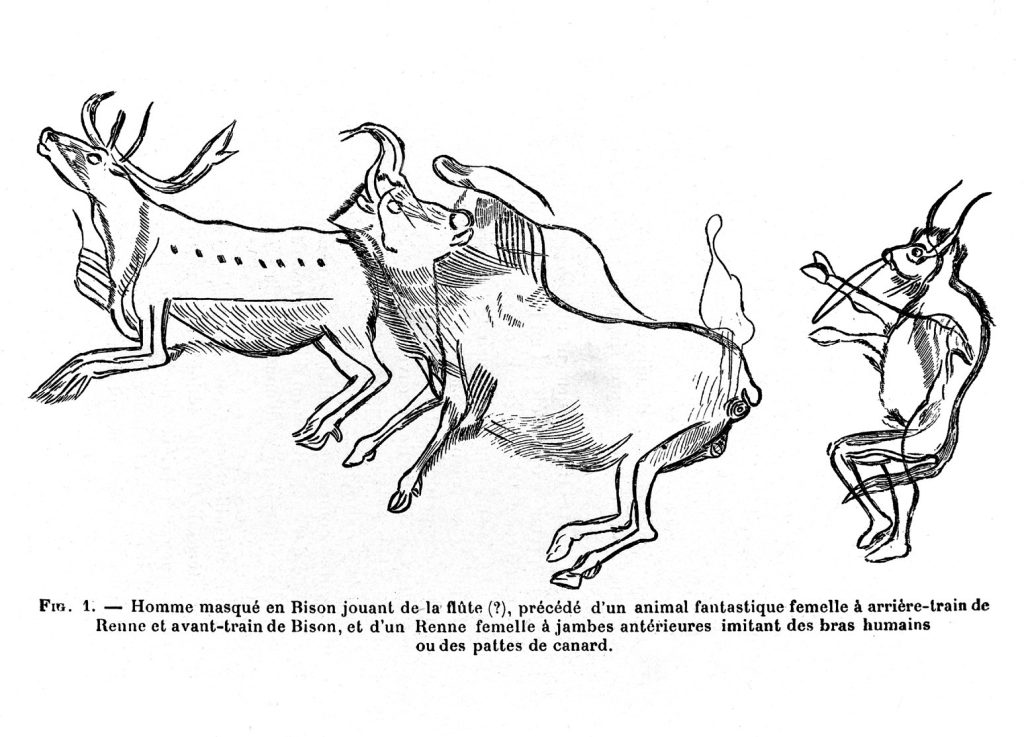

Alongside the majestic animal renderings and hands can occasionally be found stranger imagery interpreted by archaeologists as therianthropes. These can be seen, for example, in the Sulawesi cave Leang Bulu’ Sipong 4. According to a 2024 article in the science journal Nature, these creatures “are depicted with material culture objects (spears and/or ropes) and some display what can be construed as attributes of non-human animals. These figures are interpreted as representations of therianthropes (composite human-animal beings).” These hybrids, especially in earlier eras, were often rendered more schematically and at a smaller scale than the majestic animals. They have been interpreted as likely indicators of altered states and shamanism, as we shall see.

Before we proceed further, anthropology and archaeology remind us that we must be cautious about drawing conclusions from the traces of the distant past. The remains left in the protection of cave environments are only a small but piercing window into the life of our archaic ancestors. They will perhaps ever remain vitalizing enigmas that invite our gaze further and further into the mysterious depths of our origins.

One interpretive approach respected and utilized by many experts is to look to Indigenous communities today. From certain shared or universal characteristics, “ethnographic analogies” can be made to archaic cultures. When used with caution, this method can provide compelling insights. For example, experts acknowledge that indigenous cultures then, as now, almost certainly had intimate knowledge of the flora and fauna of their environment. As we will see, science suggests that psychedelic plants and fungi may very well have existed in many of these contexts of which people would likely have been aware. Similarly to Indigenous societies today, they likely maintained ecstatic traditions involving radically altered mindbody states, virtually inseparable from the dangerous entry into the otherworldly environments of many painted caves. If so, these states would have been valued to contain vital information for shamans and their communities, for the purposes of healing or guidance, for example. These nearly universal features of Indigenous societies today suggest keys to a profound understanding of Paleolithic parietal art, especially when reinforced by extensive evidence.

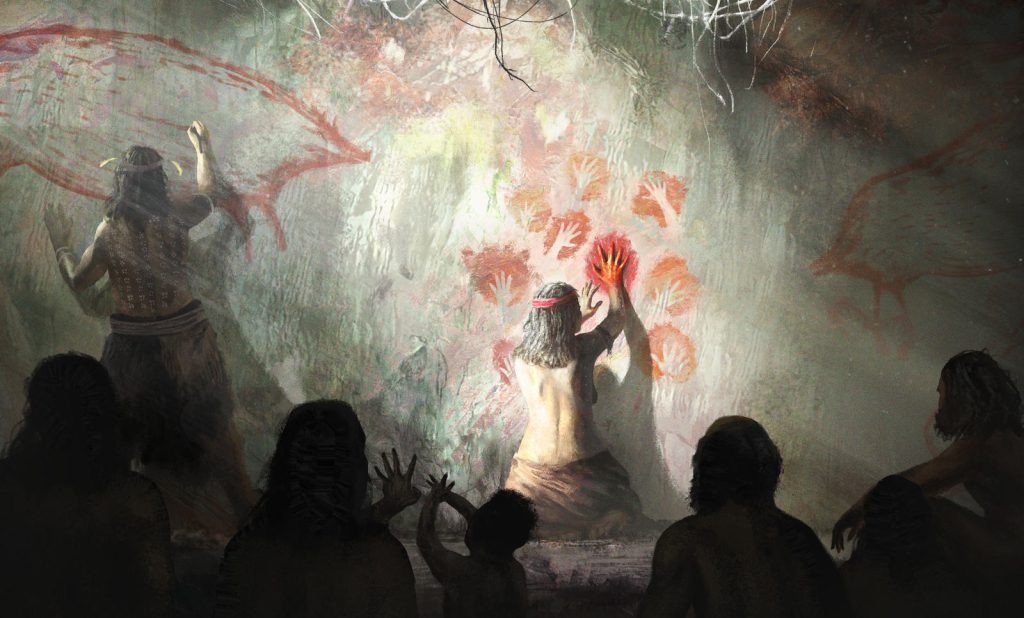

Remembrance by Rudolf Hima (2022). RudolfHima — Professional, Digital Artist | DeviantArt. Based on Sulawesi painting 45,500 years BP. Reproduced with permission.

Let us now step into the caves with informed courage and creativity in search of illumination. What is going on with these cave paintings? Remembrance (2022) by digital illustrator and paleoartist Rudolf Hima offers a compelling possibility. We are welcomed into a poignant ritualistic moment of two adults–one a woman and the other ambiguous–in the act of mark-making on a cave wall in front of a communal audience. Hima’s imagined cave is akin to Leang Tedongnge (Sulawesi), which contains nearly identical parietal imagery from at least 45,500 years BP. The most notable difference is that the real paintings were made deep beyond the reach of any possible sunlight, and thus, the painters would have seen by flickering lamps instead of the dramatic sun rays shown here. Hima, who professionally creates digital paintings of dinosaurs and other extinct species, otherwise holds true to the archaeological and anthropological research while unafraid to speculate. The vision reminds us that painters, shamans, and community leaders may very well have been women or men — we know not their sex. And although many cave environments are dangerous to navigate, some show evidence of children — including their footprints, heel prints, and even handprints (as in Pech Merle, France). We are also reminded that the ochre mineral pigments used to make hand stencils would have also covered the backs of the hands of the people who sprayed them, an intimate connection only half of which remains on the cave walls today. Many instances of cave art were likely performed in a ritual context in which an audience or communal ceremony surrounded the act of painting. Hima’s illustration invites our gaze into the profound humanness communicated by Paleolithic cave art across the eons and reminds us that community and ritual were almost certainly driving forces in many instances of their creation.

Chauvet Cave

Let us descend further into the more famous and best-documented milieu of Paleolithic art. The earliest European Homo sapiens, known as the Aurignacians, emerged around 43,000 years ago when much of the continent was covered in ice. They lived in regions also inhabited by Neanderthals, who had been present in Eurasia for over 200,000 years throughout the Ice Ages until mysteriously disappearing shortly after Homo sapiens arrived. The Aurignacians deeply explored and ornamented hundreds of caves with many series of enigmatic images.

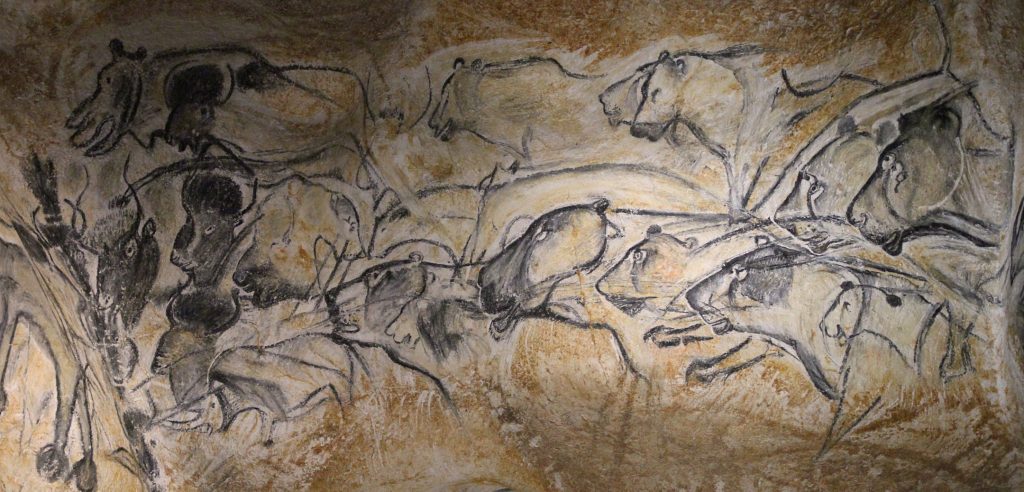

End Panel in Chauvet Cave (southern France) — appr. 30–32,500 years ago. Among the earliest known paintings in Europe, they are believed by leading scientists to have been created in shamanic contexts involving altered states of consciousness. Photo Claude Valette (CCBYSA4.0)

A spectacular and early example in France’s Ardèche region, Chauvet Cave, was only recently discovered in 1994, when it revealed the oldest known paintings in the world at the time. At 500 meters long, it contains hundreds of paintings and engravings of astonishing quality and freshness in various “galleries” and chambers. The imagery includes diverse fauna such as mammoths, reindeer, a panther, a possible hyena, bison, woolly rhinos, aurochs, cave bears, lions, and the only known instance in Paleolithic art of an owl. Typical hand stencils, positive hand prints, and patterning, along with mysterious insectoid shapes, are also present. In the renowned End Chamber, the Lion Panel–a monumental “frieze” ten meters wide–depicts “an accumulation of different animals on either side of a central niche.” (1). The cave’s 1994 discoverers, led by Jean-Marie Chauvet, wrote of their initial encounter: “It took our breath away, as, silently, we played our torches over its panels. There was a burst of shouts of joy and tears. We felt gripped by madness and dizziness. The animals were innumerable…” (2). Scores of animals from a variety of species seem to flow steadily to the left as a river of ennobled spirits, many with striking features too numerous to explore here and each compelling with its own unique attributes. Yet we can note at least two bold lions at far right each with an extra eye, and cannot help wonder about the inspiration for such a feature. Throughout, the opaque black and white pigments stand out boldly against the light beige of the wall. A member of their team also noticed “to the right, on an overhang…[was] a figure with a bison’s head and a human body which seemed to us to be a sorcerer supervising this immense frieze.” (2) Clottes later wrote: “This extraordinary individual inevitably evokes the ‘sorcerers’ of Trois-Freres in the Ariege and Gabillou in the Dordogne.” (3) The Lion Panel’s astounding composition of majestic fauna of the Ice Age Ardèche weaves a powerful narrative as compelling and beautiful as any art in the last fifty thousand years.

Stalactite with a bison-human therianthrope (on the right) called a “sorcerer” by Jean-Marie Chauvet and Clottes. Inside the End Chamber of Chauvet Cave. Photo Claude Valette (CCBYSA4.0)

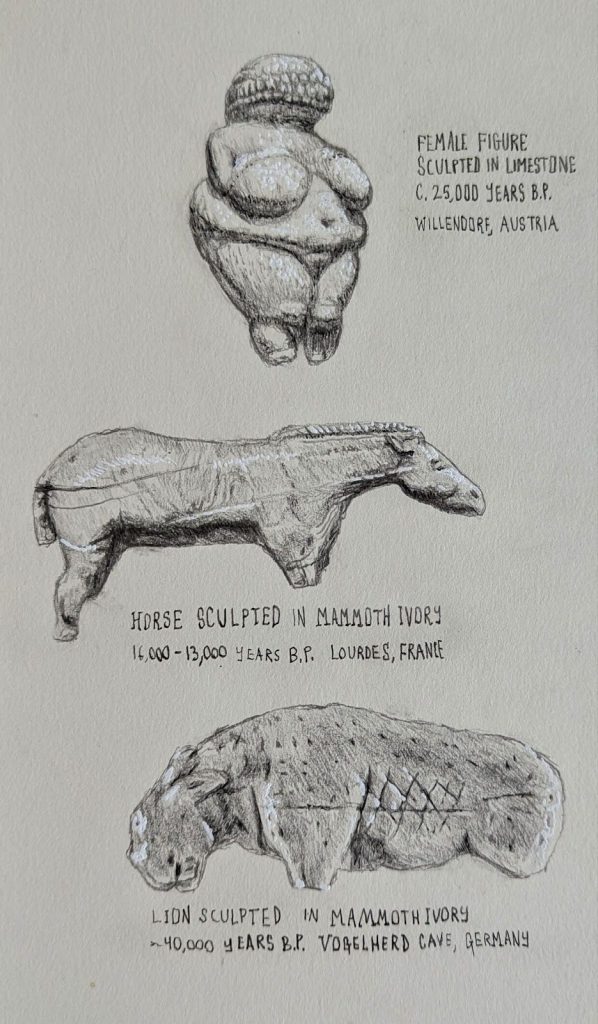

Many features of Aurignacian sites continued for tens of thousands of years into other “industries” including the Gravettian and later Magdalenian that followed. Artifacts such as stone figurines, ivory carvings, and musical instruments accompany them as well. Later eras would see rock art with similar features throughout the globe. Millennia of decorated caves, including Chauvet, Altamira (Spain), Lascaux (France), Coliboaia (Romania), Kapova Cave (Russia), Cueva de las Manos (Argentina), and hundreds more continue to beckon anthropologists, archaeologists, art historians, artists, and a growing general public with their mysterious beauty. Picasso famously commented after his visit to Magdalenian Lascaux: “We have learned nothing in 12,000 years.”

The growing public interest in parietal art can be a double-edged sword. While their discovery and study illuminates them for a wide audience, the fragile cave environments can be disturbed and even ruined by renewed human activity. Some, such as Pech Merle, have modern infrastructure to protect the art while allowing limited public access. Fortunately for others, replicas of some of the most famous caves, including Chauvet, Altamira, Lascaux, and Cosquer (Marseilles, France), have been constructed with cutting-edge technology synergizing architecture, engineering, scientific research, and artistic skill. These tourist attractions, many located near the original sites, allow visitors to comfortably experience facsimile immersive exhibitions and taste the cave experience while protecting the originals.

Other Worlds

Diverse theories concerning the meaning of Paleolithic cave paintings have been debated for more than a century—magic, hunting, fertility, story-telling, education, and art for art’s sake. Now, a growing number of experts believe that there was a shamanic element determinant in many of the cave paintings. In their book The Shamans of Prehistory (1998), renowned specialists in the field Jean Clottes and David Lewis-Williams explain:

“…entry into a cave…may also induce altered states of consciousness. The social isolation, sensory deprivation, and cold that characterize caves are, as we have seen, important factors in the induction of trance. During the Upper Paleolithic, entry into an actual cave may therefore have been seen as virtually the same thing as entry into deep trance…The hallucinations induced by entry into and isolation in a cave probably combined with the images already on the walls to create a rich and animated spiritual realm. A complex link between caves and altered states seems undeniable.” (4)

In part, this is due to the other-worldly quality of the subterranean environment. Many caves, including Chauvet, are painted not at the more easily accessible entrance but deep inside, where navigation is difficult, and daylight is far out of reach. The flickering lamp light, limited oxygen, exotic concretions of minerals, distinctive humidity and temperature, and otherworldly acoustics all likely combined to catalyze or intensify altered mindbody states. Expectations of supernatural encounters charged by hopes and fears could amplify these effects. Likely, too, is the possibility that psychedelic plants and fungi were known and also incorporated into the ritual milieu of these contexts, as we will explore below.

Evidence supports that most decorated caves were not living spaces, and some are incredibly difficult to access, especially with archaic lamp technologies. This reinforces the cave environment as a “special” or sacred space, distinct and different from the outside world. Most of the Indonesian caves are located in cramped, limestone rocky outcrops emerging above the surrounding terrain where people lived. Many European caves, such as Chauvet, have labyrinthine tunnel systems that deter leisurely entry or practical use. In his book What is Paleolithic Art? (2016), Clottes further emphasizes the shamanic theory by referring to the “prudent use of ethnographic analogy” regarding modern hunter-gatherer societies: “Throughout the entire world, deep caves are considered to be supernatural places–the domain of spirits, the dead, or deities–and their dangers can only be braved if there is well-defined and exceptional intent.” (5) This lends weight to the argument that the cave paintings were created in a shamanic context, perhaps for spiritual communication, initiation, or rite-of-passage purposes.

Looking at photographic reproductions of these fantastic paintings, we can easily forget that they were completely site-specific and made when immersed in that particular cave environment. An essential element of this is the shape and texture of the cave walls. Looking carefully at photos such as those of the legendary End Chamber of Chauvet Cave, we can notice the highly contoured surfaces. Many of the animals’ forms are amplified by the walls’ undulations, such as a round torso of a woolly rhino painted directly over a convex bulge. This must have intensified the “presence” of the animal and the painting, making it even more powerfully rendered in three dimensions.

Wolly rhinos in the Chauvet Cave End Chamber (replica). Photo Claude Valette (CCBYSA4.0)

In this sense (among others), the cave artists were visionaries in that they could “see” the animal forms suggested or hidden in the walls of the cave. In many instances, the artists did not create randomly or even in convenient locations, but rather were “inspired” by what was perceived to be spiritually present within the surface formations. They could “summon” or “evoke”, as it were, out from the walls’ forms what was already spiritually present beyond their surface. The location of some works suggest they were not made in a communal milieu but rather by a lone individual because they are found in small, cramped spaces impossible to be seen by a collective audience. Jean Clottes and David Lewis-Williams emphasize this aspect of cave art, and surely anyone fortunate enough to visit the actual caves can hardly separate the experience of the dynamic surfaces from the artworks themselves, an illusion imposed by printed reproductions that we must exercise our imagination to overcome.

Alongside many of the oldest known representational images are other marks that seem to defy translation. Zig zags, concentric arcs, parallel waves, sequences and clusters of dots, and other “abstract” patterns are abundant in many of the figuratively ornamented caves. While interpretation of these marks vary widely, David Lewis-Williams argues in The Mind in the Cave (2002) that they represent bright geometric patterns seen in the early stages of altered states. These “entoptic phenomena” are caused by the electro-chemical functioning of the human brain when entering a trance. If true, these marks could indicate the early stages of shamanic journeys, which would later bloom into full-fledged visionary content that could include the animals and other hybrid beings seen alongside them. Lewis-Williams’ model potentially accounts for a wide array of parietal art found cross-culturally on multiple continents—a transcultural visionary-artistic impetus.

Altered States and the Work of Graham Hancock

Horned therianthrope found on a stone slab inside Italy’s Fumane Cave, Aurignacian, 32–26,500 years BP. Rendition by Gregory Bart (author).

In his brilliantly exciting book Visionary: The Mysterious Origins of Human Consciousness (2022, previously published as Supernatural, 2006), Graham Hancock explores the phenomenon of Upper-Paleolithic cave art with an openness to the power of altered states and deep respect for indigenous wisdom. Unlike many experts and scientists in the field, he explored altered states directly by using psychedelics to extend his research, including journal notes from several trips in the book. His investigations led to a focus on therianthropes in the oldest collections of Upper Paleolithic figurative art in Europe at Chauvet, Fumane (Italy), and a series of caves in southwest Germany. He states in the 2006 edition how “we now know that the world’s three oldest [European] collections of figurative art all prominently feature those fabulous creatures, part beast, part human, that scholars of myth and religion label as therianthropes.” (7) The more recent discoveries in Sulawesi uncannily reinforce this generalization by featuring the same motifs as we have seen. His work also points to the recurrence of therianthropes pierced by multiple arrows or spears — representing the “wounded healer” motif that has been cross-culturally associated with shamanism (8).

A “bison man” of Trois Frere (France) alongside fauna, dated c. 15,000 years BP. Famed sketch by Henri Breuil (CCBY4.0)

Hancock’s inquiry into the origins of human consciousness led his investigations to shamanism, which opened the doors to radically altered mindbody states. His research goes further to investigate the possible use of psychedelic substances amidst the creation of the European cave paintings. He found that although the most common psychedelic mushroom species, Psilocybe cubensis, was absent from these icy regions, the species Psilocybe semilanceata, among several other psilocybin-containing species, were almost certainly abundant. “Best known as the Liberty Cap, this very popular little brown ‘magic mushroom’ is now used for hallucinatory purposes all around the world, but mycologists are unanimous as to its ancient European provenance.” (9) Hancock further describes how other natural plant psychedelics found in Europe today “such as datura, mandrake, henbane, and belladonna, are also powerfully psychotropic and would undoubtedly have produced the sorts of visions and experiences of a parallel spirit world that the cave paintings seem to reflect. Most likely, plant hallucinogens were discovered by hunter-gatherers who initially tried them out as a food; but, whatever the reason, those who ate these substances entered trance and experienced visions of a seamlessly convincing and terrifyingly real supernatural otherworld inhabited by non-physical beings. As is common in such trances–however they are induced [with or without psychedelics]–these visions would have included the luminous geometrical and abstract patterns known as entoptic phenomena, gradually merging into fully iconic hallucinations of animals and therianthropic figures.” (10)

Likely, too, would have been the distribution of natural psychedelics, including psilocybin mushrooms, in Indonesia tens of thousands of years ago. They grow abundantly there today, and the region’s history of rich biodiversity suggests they have been present for eons.

Methods of access to altered mindbody states vary across cultures (as we saw in the chapter/article on shamanism). Some examples include fasting, drumming, extended dancing, flickering light, extreme pain, dehydration, meditation, and even natural ability due to unique brain chemistry in certain individuals. As Clottes and Lewis-Williams stated in the earlier quote, entry into many cave environments may, on its own, induce altered states, especially when intensified by cultural expectation. Psychedelics, too, may have been central to the cave paintings. With whatever single or combination of catalysts, altered states emerge as an essential key to understanding parietal art along with their deeper implications.

Hancock concludes in the 2022 edition of Visionary that “All the imagery of the painted caves, whether created by Neanderthals or by anatomically modern humans, is characteristic of visions seen in deeply altered states of consciousness, most likely brought on by the use of psychedelic plants and fungi.” (11) Clearly, we cannot pretend to literally translate the particular symbolic lexicon of Paleolithic cave paintings. Yet when we acknowledge the intimacy between altered mindbody states and Upper-Paleolithic parietal art, we discover an electrifying insight into the past that can charge our vision today with a force shared by humanity for tens of thousands of years. This spark is the validation of our unique capacity for altered states and an affirmation of the imaginal phenomena perceived therein as powerfully, if not mysteriously, relevant to human life, particularly when experienced in a sacred space. When we value radically altered states–and, by extension, shamanism and psychedelics–as an essential aspect of humanness, we are gifted with a wider spectrum of ourselves and a greater reservoir of wisdom to connect with our Upper-Paleolithic ancestors and channel the same ennobling powers we see in their art to address our world today. Hancock has courageously (and controversially) explored many ancient enigmas with this valuation, and here, it serves us well in discerning essential threads woven through the history of art. Both the archaic cave artists and visionary artists today step further by interacting with these imaginal worlds by engaging them through creative expression. As we will see throughout the history of visionary art (check out my other articles), this endeavor will transform through endless historical permutations, continually revealing an infinite reservoir of potent imagery to be unleashed from the unseen world.

The Mystery Remains

If it is true that radically altered states were intimate to archaic cave art, the mystery of human creativity is compounded rather than explained away. For we today can be just as awed, overwhelmed, and inspired by visions seen in altered mindbody states as those peoples tens of thousands of years ago. By engaging these visions creatively we share in the perennial human endeavor of visionary art in all its power. The courage to enter and create in imaginal realms leaps across the eons as an affirmation of the nobility of humanity and our place in some greater spiritual world. This mystery affirms not only creativity as a miracle but also a greater embrace of what it means to be human. This leads us to one final illuminating insight. Though the particular cave art we have explored here is accompanied by strong evidence of Homo sapien artists, growing evidence is emerging that Neanderthals and other members of the wider human family too may have shared spiritual concerns and expressed forms of culture and “art”, even likely earlier than Homo sapiens, in other caves and environments. Indeed, as we continue to study the oldest artworks left by our ancestors, the divisions in time, space, humanity, and nature continue to dissolve until all that remains is an interwoven creative continuum of which we are part.

Since I first began to learn about the paintings from Chauvet, and then many other wondrous ornamented caves, I wanted to somehow participate in a shared endeavor with these early human “artists”. The sciences that study them, such as anthropology and archaeology, are some ways to dialogue with and learn from archaic cave art today. Science clearly has its essential place in exploring the cave paintings, yet I believe artists, too, have a role in engaging their enigmas with approaches outside the purview of science. There remains the creative angle—for artists to creatively dialogue with parietal imagery and their imaginal contents. As we have seen, many of these discoveries are fresh and exhilarating–made only in the past few decades–and offer a fresh reservoir of art historical treasure for artists to process and integrate in their own unique ways.

For me, the animals in the caves always had a charge of purity and power. Their majestic presence is clean and utterly poetic. I embraced this attraction by sketching and studying them, and then integrated their particular imagery into larger works. Archaic Renaissance Triptych (2023, digital painting) is an energized vision with diverse references to specific Upper Paleolithic artworks woven into an epic hieratic presentation. The main panel centers on a titanic therianthrope, with the arm of a man and a head akin to a lion with antlers. Beside him enigmatically sits a man clothed in another era — in fact, this is a close rendering of Michelangelo’s sculpture Medici Penseriosa (c.1520). He sits confidently atop the rocky protrusion as master of Renaissance knowledge while suggestively gesturing to the titanic therianthrope.

Beaming from the therianthrope’s hand is a sequence of glowing equestrian heads sampled directly from the Panel of Horses in Chauvet. Beside them lies the skull of a sabretooth tiger, the terrifying beast which likely haunted the darkness beyond the campfires of early humans for eons. At the bottom, we see a cluster of psilocybin mushrooms blooming from fractured rock, honoring the enduring psychedelic element in the powers of vision. At the upper right, we can discern amidst luminous clouds the formation of the nebula Pillars of Creation, among the most famous images revealed by NASA’s Hubble and later WEBB telescopes.

Panel of Horses in Chauvet Cave c. 31,000 years BP. Though to our eyes they may all look similar, experts discern particular ages and behaviors in the expressive portraits. Public Domain

The left panel glorifies one of the oldest known therianthropic sculptures, known as the Lion Man of Hohlenstein-Stadel (Germany), roughly 40,000 years old, made from mammoth ivory. His form is complemented in the right panel by the voluptuous goddess figurine of Willendorf (Germany) of around 30,000 years ago made from limestone. Behind each figure is a complex pattern inspired by Islamic design, not to emerge until tens of thousands of years later. Resonances between these different eras and regions, with emphasis on archaic art from humanity’s deep past, are explored with a guiding intuition that keys to our survival and success today can be found through a renewed Renaissance of our archaic, shamanic origins. In bridging together diverse aesthetic currents—from archaic art, psychedelic empowerment, Renaissance cultural transformation, Islamic infinities, and scientific imaging—perhaps we can intuit an awesome unifying force in the perennial power of vision unlocked through the diverse industries of human consciousness.

When we look at the oldest art and its milieu, we look down a vast corridor through time, a distance short-circuited by our glimpse into the caves of some mysterious and fundamental power that humanity never lost but had forgotten for millennia. Spirits of the earth seem to speak themselves through the work of human hands, as if we are catalysts for a greater spiritual message or transmitters of the mind of nature itself. Are we the species destined to manifest nature’s imagination? Are we a catalyst for ecological transformation? Are we the Earth’s best opportunity to extend biology beyond the planet’s surface to other worlds? What is the message of nature now amidst the impact of global civilization? As we will see, later ages of visionary art will continue to present an enduring and formidable validation of spiritual dimensions beheld by those earliest known artists, with each successive age exploring newfound portals into imaginal realms and creatively transmitting the mysteries they hold.

Lions at far right of Lion Panel, Chauvet 2. Its discoverers wrote, “One of the lions seemed to dominate the pride with its penetrating gaze; its head was drawn with darker lines.” (12). Photo Claude Valette (CCBYSA4.0)

Thank you so much for reading!

This article is part of a series exploring visionary art, which I unabashedly argue to be the most powerful and relevant art today. These articles will feature in my upcoming book: Visionary Art — from its ancient origins to today’s painters at the vanguard of cultural transformation.

Readers are invited to ask questions and comment! Check out my other articles on Medium.com, which include an Introduction to Visionary Art as well as features on visionary artists from diverse historical ages and places, including Michelangelo and Luke Brown.

To dive in and further explore visionary art — its history, shamanic connections, and its past/present/future artists including Michelangelo, William Blake, Amanda Sage, Luke Brown and more — visit my Medium profile page.

Comments, questions, and thoughts are very much appreciated.

Opening image: Digital painting inspired by a Lascaux horse by Gregory Bart (author).

My artwork can also be found at www.artmindstudios.com.

Special thanks to Graham Hancock for your courageous research, inspiring message, and for presenting this article on your website!

Works Cited (Books; articles are hyperlinked):

1. Chauvet, Jean-Marie; Deschamps, Eliette Brunel; Hillaire, Christian; Clottes, Jean: Dawn of Art: The Chauvet Cave. Abrams, 1996. p. 106

2. See 1, p. 58

3. See 1, p. 110

4. Clottes, Jean; Lewis-Williams, David: The Shamans of Prehistory. Abrams, 1998. p. 29

5. Clottes, Jean: What is Paleolithic Art? University of Chicago Press, 2016. p. 17

6. Lewis-Williams, David: The Mind in the Cave. Thames and Hudson, 2004.

7. Hancock, Graham: Visionary: The Mysterious Origins of Human Consciousness (previously published as Supernatural, 2006). New Page, 2022. p. 62

8. See 7, p. 227

9. See 7, p. 189

10. See 7, p. 238

11. See 7, p. XX

12. See 1, p. 58

Copyright © 2025 Gregory Bart. All rights reserved.

In the Past so Wild and free,

Today domesticated and pay fees.

The thing about the Chauvet cave art is not only how damn good it is, it is how French it looks for 35,000 years ago. The style is identifiably French, reminiscent of Callot or Matisse in its graceful, musical line work. If anything it is of higher quality than modern art, but yeah, it always struck me as bizarre that something from an epoch when France was mostly glaciers could somehow express an identifiable modern style. Minoan art is similar in that respect. And to think the good stuff, the really good stuff, is probably under water, miles out to sea and lost forever, or possibly still buried somewhere, awaiting rediscovery.

Nothing is new under the sun.

Great thought…there is an ascended, floating quality in many cave paintings that Matisse conveys in his work, a kind of liberation from the weight of physicality. It seems artists in various ways and to varying degrees are tapping into sources beyond the personal and expressing them into their culture as an objective nourishment – like water for a plant.

And I find your last thought inspiring as well – there will always be more to discover, within and without…

Cheers, Gregory. Yes, the floating quality as well as the actual line work and composition looks stylistically French to me. My inner radical conspiracy theorist wants me to consider the notion of it all being modern hoaxes so much does it look out of place. Almost too good to be true! A tourist trap made by the French government? If government-approved academics are the gatekeepers how would we ever know?

Great article too by the way, I did actually mean to say so the first time, sorry, the images took over! I will have to re-read it as there is so much in it. Graham’s exploration of this entire realm is unique in my knowledge. Imagine going miles deep into caves, as our ancestors did, miles underground, with only stone age technology to help you, and then creating sublime works of art right there, in the innards of earth, for thousands upon thousands of years. It boggles the mind. This cave is not so deep but others are.

I left out Chagall too. And it isn’t as simple as omitting an horizon line to create the sense of abstraction. The Herzog documentary Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2009) focuses on these caves, whenever I show anyone they tell me it is the best thing they have ever seen. Highly recommended.

With things like this and the Tas tepeler culture and cappadoccia-type discoveries, I cannot look at hills or mountains or even plain flat ground the same way any more. They may not be hills or mountains at all, but art galleries, cathedrals, the ground beneath our feet may well be the roof of an ancient haven used as such for longer than an epoch or two – who knows what stories took place, which epic dramas unfolded for ages and aeons untold? And the inland stuff like this is just what we have access to. The richer culture and better art would have been coastal, now submerged.

What were they ON???

Great Bob! Much agreed, I think Cave of Forgotten Dreams was an early portal into this for me as well. Anyway I like Graham’s point about humanity’s amnesia of the past. A lot of media and politics (to generalize) seems to fixate our attention on the distractions of the moment rather than opening us to the expansive scope of human history over millennia, over thousands of years of dynamic societies, arts, and mindbody states that we would do well to tune in to, in order to really face the challenges of our times. The Paleolithic art seems to point to a heroic aspect of humanity that was probably intimate to our very evolution, to the grander scale of our higher capacities. Beneath the earth and surely beneath the waves are surely more hidden gems to glorify the best in us and humble the worst in society today.

Absolutely agree! The present is very much a deliberate distraction from the past. A kind of attention-rape.

The only issue I have with Graham’s rhetorical quip about being a species with amnesia is, there aren’t any other kinds lol. Find me a parrot or a dog that knows how it got there!

But yes how the hell could we have forgotten so much that ppl were obviously around for. Weird.