On Saturday the 3rd of April the Adelaide Festival hosted a public showing of Australian Atomic Confessions, a documentary I co-directed about the tragic and long-lasting effects of the atomic weapons testing carried out by Britain in South Australia in the 1950s.

Amid works from 20 artists reflecting on nuclear trauma as experienced by Indigenous peoples, the discussion that followed brought up the ways in which attempts at nuclear colonisation have continued in South Australia, and are continuing right now.

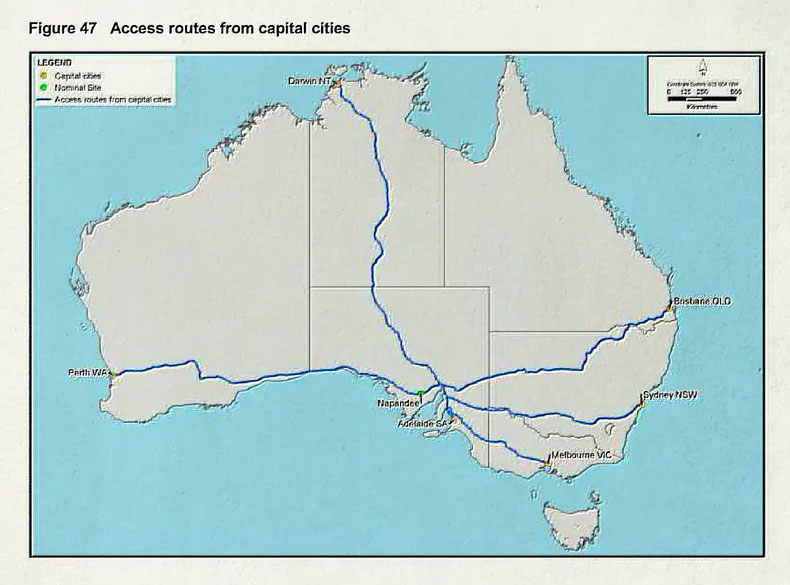

For the fourth time in 23 years South Australia is being targeted for a nuclear waste dump — this time at Napandee, a property near Kimba on the Eyre Peninsula.

The plan is likely to require the use of a port, most probably Whyalla, to receive reprocessed nuclear fuel waste by sea from France, the United Kingdom and the Lucas Heights reactor in NSW via Port Kembla.

Napandee. Site Characterisation Technical Report. Department of Industry

The waste will be stored above ground in concrete vaults which will be filled for 100 years and monitored for a further 200-300 years.

Nuclear waste can remain hazardous for thousands of years.

The Barngarla people hold cultural rights and responsibilities for the region but were excluded from a government poll about the proposal because they were not deemed to be local residents.

The 734 locals who took part backed the proposal 61.6%

The Barngarla people are far from the first in South Australia to be excluded from a say about proposals to spread nuclear materials over their land.

It’s not the first such proposal

Australian Atomic Confessions explores the legacy of the nine British atomic bombs dropped on Maralinga and Emu Field in the 1950s, and the “minor trials” that continued into the 1960s.

After failed clean-ups by the British in the 1960s followed by a Royal Commission in the 1980s, the Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency conducted a cleanup between 1995 and 2000 it assures us was successful to the point where most of the contaminated areas at Maralinga fall well within the clean-up standards applied for unrestricted land use.

But experts remain sceptical, given the near-surface burial of plutonium and contamination remaining across a wide area.

The Tjarutja people are allowed to move through and hunt at the Maralinga site with their radiation levels monitored but are not permitted to camp there permanently.

We are told that what happened in the 1950s wouldn’t happen today, in relation to the proposed nuclear waste dump. But it wasn’t our enemies who bombed us at Maralinga and Emu Field, it was an ally.

In exchange for allowing 12 British atomic bombs tests (including those at the Monte Bello Islands off the northern coast of Western Australia), the Australian government got access to nuclear technology which it used to build the Lucas Heights reactor.

It is primarily the nuclear waste produced from six decades of operations at Lucas Heights that would be dumped onto Barngarla country in South Australia, closing the links in this nuclear trauma chain.

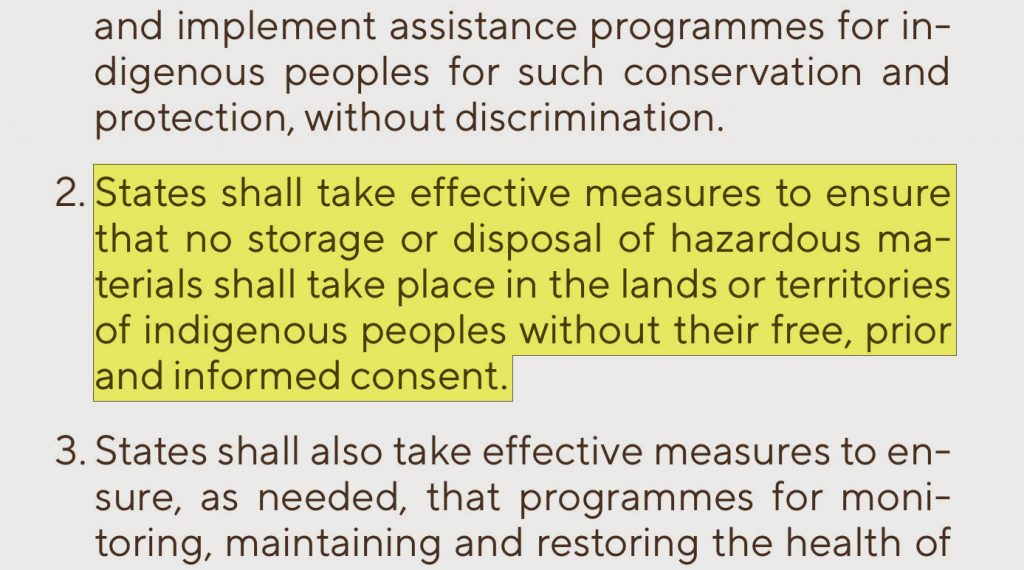

Nuclear bombs and nuclear waste disproportionately impact Indigenous peoples, yet Australia still has not signed up to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The declaration requires states to ensure there is no storage or disposal of hazardous materials on the lands of Indigenous peoples without their free, prior and informed consent.

Nor has Australia shown any willingness to sign up to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons which came into force on January 22 this year after a lobbying campaign that began in Australia and was endorsed by Indigenous leaders worldwide.

Aboriginal people have long known the dangers of uranium on their country.

Water from the Great Artesian Basin has been extracted by the Olympic Dam copper-uranium mine for decades. Fragile mound springs of spiritual significance to the Arabunna People are disappearing, posing questions for the mining giant BHP to answer.

Australian uranium from BHP Olympic Dam and the now-closed Rio Tinto Ranger mine fuelled the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster.

Senior traditional custodian of the Mirrar people, Yvonne Margarula, wrote to the United Nations in 2013 saying her people feel responsible for what happened.

It is likely that the radiation problems at Fukushima are, at least in part, fuelled by uranium derived from our traditional lands. This makes us feel very sad.

The Irati Wanti (The Poison, Leave It!) campaign led by a council of senior Aboriginal women helped defeat earlier proposals for nuclear waste dumps between 1998 and 2004.

There remains strong Indigenous opposition to the current nuclear waste proposal.

Over the past five years, farmers have joined with the Barngarla People to protect their communities and the health of the land.

In 2020 the government introduced into the Senate a bill that would do away with traditional owners’ and farmers’ rights to judicial reviews and procedural fairness in regard to the use of land for the facility.

Resources Minister Keith Pitt is deciding how to proceed.

Originally published on theconversation.com

Exploitation of peoples and environments require consent. Unfortunately, consent is assured by some temporary gain. By examples such as civil war on Easter Island (Rapa Nui), and the rat colony experiment named Universe 25, we remain our worst enemies. Certain inevitable processes of self-destruction are activated by certain levels of population density. We want to send waste ‘away’ but we have run out of ‘away’ places. The only practicable lessons here are in consent and enforcement. Our intuition is to use and abuse, and to support constitutions and leaders who allow us to do that.

Most Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs), and Public Participation Processes (PPPs) by Interested and Affected Parties (I&APs), are lessons in the slow but fatal flaw in the most successful species on the planet. Our fate is sealed by our own waste in the water, air, soil and ether that we have taken charge of. Thank you for bravely raising awareness of the human tragedy.

Thank you Edmond, so true. When will we learn? In going back and learning about our own ancestral connections to place and country, we might gain some respect for those places we were previously so disconnected from. All the best!

The weathy ruling claas donm’t really care about ordinary people

A very important topic to discuss at what is shaping up to be a crucial time for not only the state, but the country, Australia’s political landscape appears to be pushing the energy crisis topic to the forefront, also the agreement with the USA over Australia receiving Nuclear submarines in the future, coupled with the sudden concerns by the Albanese government with climate change now it realises that strategic allies in FIJI are required to stall Chinas fiscal advance into the region, is only further applying pressures to what is shaping up to be a political hot potato.

One hopes that all people survive the onslaught capitalism and consumerism has had thus far and learn to live in a more harmonious existence not only with nature but also with one another.