I started this adventure as a simple “one post” blog. It seemed a vaguely interesting idea; a possible link between Moses, who led the Israelites out of bondage to the Promised Land, and Akhenaten, the heretical Pharaoh who overturned the religion of Egypt. Moses is revered in various religious texts, yet apparently lacks any proven historicity, while Akhenaten, although only really “rediscovered” in the twentieth century, certainly existed, however, nearly all his buildings, monuments and inscriptions were deliberately destroyed. What is it about these two characters from ancient history that has fascinated academics, religious writers and the world at large for generations? Was it pure coincidence that both were linked to religious movements which were seen as controversial in their time, or was there more to these two leaders of men? Two larger than life characters should be easy to identify in the historical and Biblical texts. How wrong I was. It has grown into an unbelievable jigsaw puzzle that has led me down some very interesting paths.

Although what follows is only a small part of what eventually became my book, Moses and Akhenaten: Brothers in Alms, it is a particularly fascinating story in its own right. Many authors, researchers and scientists have written of the events of the Exodus with various theories being put forward and I openly acknowledge all of their work. Struck by Freud’s ideas that Moses was an Egyptian and probably one of high rank, I was led to the belief that Akhenaten and Moses were not the same person, but were related – in fact were brothers. I decided that the way forward was to read as much as is available concerning these two iconic leaders of men. My research, added to that of others, has not proved a direct connection between the two, but, perhaps more importantly, it has not proved that there wasn’t.

The premise is that Moses was the son of Amenhotep III, the Crown Prince Tuthmose, who disappears from the records sometime around his father’s thirtieth year. His exile from court paved the way for his younger brother to eventually take the throne as Amenhotep IV, or Akhenaten, as he is better known. As princes growing up in the cosmopolitan world that was the empire of Amenhotep III, along with the leanings within the royal family towards a return to the older religions, they experienced a distinct separation from the influences of the Amun-Ra priesthood. From these influences grew the early forms of monotheism that both brothers would follow in later life. Drawing on ancient texts and inscriptions it is possible to gain some idea of where Moses really was during the biblical forty years that he was in Midian. The end of the 18th dynasty gave Moses the chance to reclaim his birthright and he returned to Egypt to face the new king, Ramesses I. It is from this meeting that the events that we know as the Plagues and the Exodus followed. It is important to understand that Pi-Ramesses is to be found at the site of the fortress Zarw and that the eruption of Thera has just taken place. These details are all explained in Moses and Akhenaten: Brothers in Alms.

The actuality of the Exodus has probably generated the most discussion and argument in history. The fact that the Exodus is not referred to in Egyptian documents does not in any way mean that it didn’t take place. The Egyptians were masters of spin and never held back in rewriting their own history to maintain the balance of Maat. With the death and destruction brought about by the earthquakes that hit the eastern Delta, Pharaoh was only too keen to let Moses and his followers go. According to the Bible, the Israelites were given everything that they might need for their journey, as well as gold and silver; such was the urgency of the Egyptians to get rid of them.

The earth tremors linked to the possibility of extreme high tides, even tsunamis, would have made the coastal route a dangerous prospect for the fleeing Israelites. These natural threats, added to the distinct likelihood of the Egyptians changing their minds about losing such a valuable workforce, would have made the Way of Horus, with its military garrisons, the worst possible route out of the country.

Moses led the Hebrews this way, that in case the Egyptians should repent and be desirous to pursue after them, they might undergo the punishment of their wickedness, and of the breach of those promises they had made to them. As also he led them this way on account of the Philistines, who had quarrelled with them, and hated them of old. (Antiquities of the Jews, Josephus)

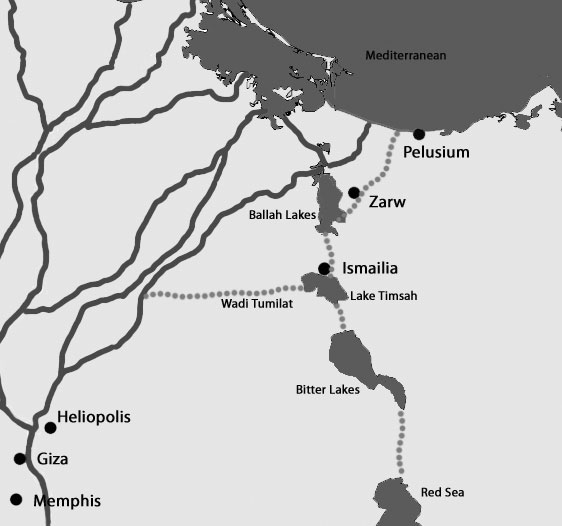

The Land of Ramesses and Goshen were interchangeable names to the Biblical editors, and so the Israelites left the area of Ramesses heading in a south- westerly direction. The entire Eastern Frontier network, with its lakes and adjoining canals, sections of which were more than 230 feet (70 m) wide, stretched from the Mediterranean to the Gulf of Suez, acting as a physical barrier between Egypt and the Sinai. This made it virtually impossible for the Israelites to travel directly east, and they were forced to head in a different direction in search of the Way of Shur, the old caravan route that led from Canaan, across the Negev, to the eastern edge of Egypt where it passed through the Wall of the Ruler, just north of Lake Timsah, at present day Ismailia. Shur comes from the Hebrew word shuwr meaning wall or enclosure andappears several times in the Bible, always in association with Egypt: “unto Shur, which is before Egypt” (Genesis 25), “thy going in to Shur, which is on the front of Egypt” (Samuel 1) and of course Exodus, where the Israelites journey three days into the Wilderness of Shur.

Travelling south-west, with the horizon behind them broken, during the day, by the stratospheric reaches of the ash plume from Thera, and by night, the glow from the lava fires, they skirted the western shores of the then extant Ballah Lakes. As they journeyed, the sheer numbers of people, along with their herds of sheep, goats and cattle, would have made travelling heavy going and it is likely that they would have been forced to make camp as they crossed into the 8thnome, known as the Eastern Harpoon. This was the first stop, somewhere to the north of the Wadi Tumilat, a makeshift camp known to us as Succoth, widely translated as tents or booths; perhaps a reference to the shanty-like shelters built by the travellers. The Israelites were now in the general area known to the Egyptians as Tjeku. Although part of Egypt proper, references to Tjeku are usually accompanied by the determinative glyph that denotes the desert or foreign lands, implying a foreign border or even extensive habitation by foreigners; sometimes Tjeku is given the city determinative providing a good reason for assuming it was a specific locale as well as a region. Various 19th Dynasty letters from an official on the Eastern frontier show the importance of the Tjeku region in the control of the border.

We have finished passing the tribes of the Shasu of Edom through the Fortress of Merneptah-Hotephirma, Life, Prosperity, Health, in Theku, [Tjeku] to the pools of Pithom, of Merneptah-Hotephirma in Theku, in order to sustain them and their herds in the domain of Pharaoh, L.P.H., the good Sun of every land… (Papyrus Anastasi VI, Ancient Records of Egypt vol. III, Breasted)

Another matter, to wit: I was sent forth from the broad-halls of the palace-life, prosperity, health!-in the 3rd month of the third season, day nine, at the time of evening, following after these two slaves. Now when I reached the enclosure-wall of Tjeku on the 3rd month of the third season, day 10, they told me they were saying to the south that they had passed by on the 3rd month of the third season, day 10. Now when I reached the fortress, they told me that the scout had come from the desert saying that they had passed the walled place north of the Migdol of SetiMer-ne-Ptah–life, prosperity,~health! Beloved like Seth. When my letter reaches you, write to me about all that has happened to them.(Papyrus Anastasi V, Ancient Near Eastern Texts, Pritchard)

It is worth noting that it only took one day for the writer of the above to get from the palace, i.e. the royal residence, which one would presume was Ramesses, to the walls of Tjeku. An easy journey if one follows the canals of the Eastern Frontier.

The principal deity of Tjeku was Atum, itm, the creator god, head of the Ennead, whose main centre was Heliopolis, and the name Pithom and possibly even Tumilat and Timsah all carry a reference to that god. pritm or Pithom means the house of Atum and many references to Tjeku attest the link. Naville’s work describing his excavations at what he believed was Pithom, includes a picture of a statue of a priest with the titles Overseer of Prophets of Atum and Chief Priest over Tjeku, and mentions all the priests …who shall enter the temple of Atum…residing in Tjeku.

Inscribed by Ptolemy II, more than a thousand years after the time we are interested in, the Pithom Stela, discovered at Tell el Maskhuta in the WadiTumilat, links Tjeku with Atum many times: itm a3 nTranx n Tkw, Atum, the great living god of Tjeku. Another noteworthy section from the same stela mentions both the canal and the wall:

In the year 16… they dug [dredged] a canal, to please the heart of his father Tum, the great god, the living of Tekut [Tjeku], in order to bring the gods of Khent-ab [the Sethroitenome]. Its beginning is the river north of Heliopolis, its end is in the Lake of the Scorpion [Lake Timsah], it runs towards the great wall on its eastern side, the height of which is hundred cubits… (>The Store-City of Pithom and the Route of the Exodus, Naville)

If cubits is the correct translation, the wall would have been over 150 feet (45 m) high.

Having left the makeshift camp of Succoth, the Israelites continued south and then east along the Wadi Tumilat until they reached their next stop, which, according to the Bible, was Etham. Although its actual location hasn’t been established, Exodus tells us it was at the extremity of the wilderness, in other words, on the edge of the desert, at the eastern end of the wadi. Again the influence of Atum or Tum is clear in the name. Professor Kitchen, in his On the Reliability of the Old Testament, suggests that the name could have come from iw-itm, an isle of Atum, rather than the oft repeated association with the Egyptian word khetem meaning fort, which linguistically is not possible: the Hebrewaleph cannot come from the Egyptian kh.

At Etham, the travellers find themselves forced into turning north, as the Shur, the enclosure or wall that protects the Eastern border, prevents any further travel east; to the south lie the waters of Lake Timsah and the route back is impossible as the Egyptian forces, as predicted, are now heading east along the Wadi Tumilat in pursuit of the fleeing work force.

We have acted foolishly in allowing these slaves to leave us. We shall miss their services in the manufacture of bricks, and in building up our fortresses. When our tributaries hear of this tiling, they will rebel against us, unless we take severe measures with these Israelites, for they will say, ‘If slaves can successfully rebel against them, how much easier will it be for princes and rulers like ourselves to cast their yoke from off our necks.’ Therefore Pharaoh assembled his wise men, his magicians, and his elders, and taking counsel together they resolved to pursue and recapture their bondsmen. (The Talmud: Selections, Polano)

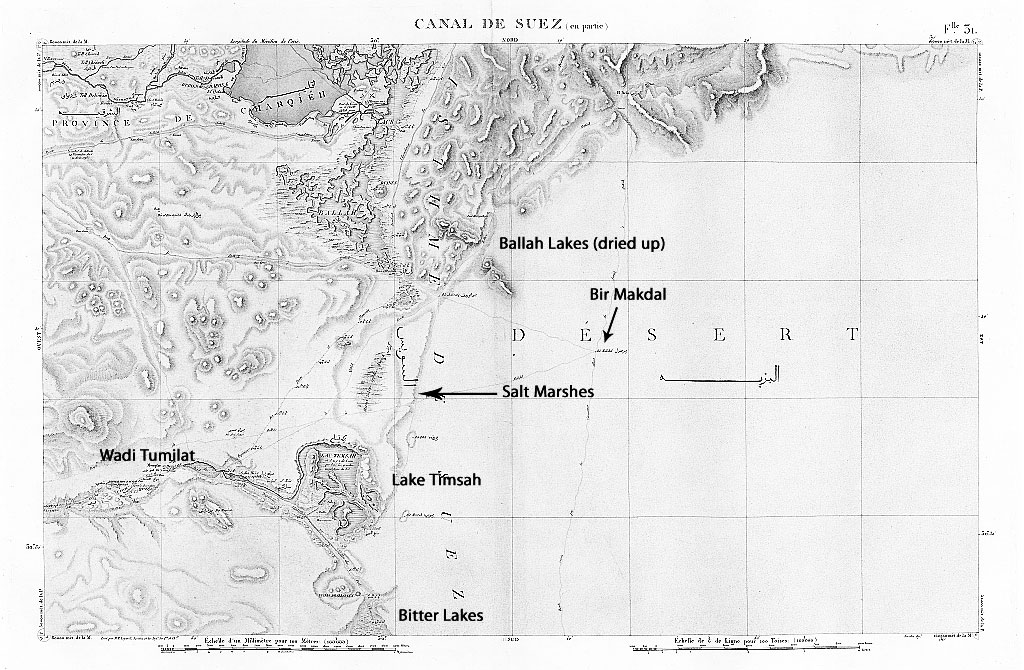

The Description de l’ Égypte was the collective output of the scholars and scientists who accompanied Napoleon on his three year expedition to Egypt. As part of this work, a series of maps, known as the CartesTopographique de l’ Égypte, was published in 1818. Six miles (10 km) north-northeast of Lake Timsah lay the Ballah Lakes separated by what the Napoleonic cartographers labelled Marais Salans, salt marshes.

Although not shown on the 19th century map, today’s satellite imagery clearly shows the remains of an artificial waterway north of Ismailia, a few hundred metres from the Faculty of Medicine of Suez Canal University. This is part of the canal system discovered by the French engineer Linant de Bellefonds, who wrongly attributed the work to Necho of the 26th Dynasty. More of this canal was revealed by the aerial photography of the Israeli Geological Survey carried out in the 1970s. The visible section, north of Ismailia, presumably connected Lake Timsah with the Ballah Lakes. Although geological evidence suggests that the lake systems across the Isthmus of Suez were at times dry, it is likely that, with the canal systems operational at the time of the Exodus, the basins would be full, providing a defensive line along the eastern boundary with the desert. If the canal with its raised banks is the Wall of the Ruler, built as a defence rather than for navigation, then after the expulsion of the Hyksos, it would have been comparatively simple for the kings of the 18th Dynasty to dredge out the old earthworks.

Jehovah speaketh unto Moses, saying, “Speak unto the sons of Israel, and they turn back and encamp before Pi-Hahiroth, between Migdol and the sea, before Baal-Zephon; over-against it ye do encamp by the sea,” and Pharaoh hath said of the sons of Israel, They are entangled in the land, the wilderness hath shut upon them. (Exodus 14)

Four specific points that should make it possible to determine the Israelite crossing point.

The Papyrus Anastasi III carries a letter from one scribe to his superior in which he describes arriving at the Royal Residence, Pi-Ramesses. He waxes lyrical about how the Residence is “pleasant in life, its field full of everything good,” he also mentions the canal of the Residence and the plentiful supply of fish. In one of the lines the scribe describes the fish of the “x… waters, waters of Ba’al,” unfortunately the name of the water where the fish are is damaged; however, enough of the determinatives have survived to suggest that the water in question was a canal. The text continues with a reference to two more stretches of water: “The Shi-Hor has salt and the pAhrw has natron…” Hoffmeier, in his Ancient Israel in Sinai, has suggested that the word hrw could be a borrowed derivation of a Semitic word meaning canal, and the Pi of Pi-hahiroth is actually the Egyptian definite article giving us the canal. The scribe continues with his description talking of the pATwfy and its papyrus and the Shi-Hor with its rushes. pATwfy is the name that has been widely translated as yam suph, the Sea of Reeds.

The debate over the translation of yam suph either as the Sea of Reeds as opposed to the traditional Red Sea has filled many books, and is an argument we are not going to get into here. Most scholars now accept the former translation, with some suggesting that the term is an all-encompassing one covering all of the wetlands across the Isthmus, including, possibly, the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aqaba. The use of the word sea must be understood to refer to any large stretch of water, for example the Sea of Galilee or the Dead Sea and does not necessarily mean sea as we would use it today. Modern German still uses the same word see to mean either a lake or the sea.

With the sea (Lake Timsah) behind them and Pi-hahiroth (the canal) on their left, the Israelitesturn back as they head north in the direction of the Ballah Lakes, Baal-Zephon. Baal-Zephon simply means Baal of the north and perhaps the storm god’s name lived on in the now non-existent lake system.

It must be pointed out that neither Hebrew nor Egyptian hieroglyphs recognize capital letters, so many of these words and places have perhaps attained a greater specific importance than was originally intended. A good example of this is Migdol, which means tower. It has been assumed that the Migdol in question will be found in the remains of a substantial fortress and all sorts of links have been made to various Migdol that are referenced in the Bible. It has become the Migdol, when perhaps it should be a migdol.

From the viewpoint of the Israelite camp, before the canal, with the lakes in front of them and the “sea” behind them, the Napoleonic maps show that about 12 miles (20 km) east of the present day Suez Canal, equidistant between Ballah and Timsah and overlooking the French salt marshes, stands the BirMakdal, the “well of the tower”. This site today appears to be covered by the desert sands.

Cartes Topographique de l’ Égyptemap showing marshland between Timsah and Ballah lake systems as well as Bir Makdal

The original agreement with Pharaoh was to allow the Israelites three days to go into the wilderness for a religious festival, which in effect gave them a three day head start.

Now that the children of Israel had gone from them the Egyptians recognized how valuable an element they had been in their country. In general, the time of the exodus of Israel was disastrous for their former masters. In addition to losing their dominion over the Israelites, the Egyptians had to deal with mutinies that broke out among many other nations tributary to them, for hitherto Pharaoh had been the ruler of the whole world. (Legends of the Jews, Ginzberg)

Then Pharaoh sent heralds to all the Cities, Saying: "These Israelites are but a small band, and they are raging furiously against us; but we are a multitude, amply fore-warned.(The Holy Qur’an, tr. Abdulla Yusuf Ali)

Pharaoh finally caught up with the fleeing Israelites as they were about to cross into the Wilderness of Shur. Again, we need to relook at the Exodus story, where we find that Pharaoh chased after Moses and his followers by chariot, in fact 600 chariots, and it was these fast weapons of war that had enabled the Egyptian forces to catch up so quickly. However, it was these very chariots that would prove Pharaoh’s undoing. Moses led his people straight through the yam suph, the salty marshes of the French cartographers, which lay between Timsah and Ballah, and Pharaoh in his eagerness followed suit. The wet, boggy ground allowed the Israelites to pass, while stopping the faster, but much heavier, chariot pursuit dead in its tracks. Moses and the Israelites left Egypt.

Whether or not the king died at yam suph is open to interpretation, but it is certain that Ramesses I died unexpectedly and was buried hurriedly in the Valley of the Kings. His tomb is noted for being only partially complete. His son and heir, Seti I, conducted vigorous campaigns into Syria and Canaan.

Wonderfull story and the evidence makes it a compelling read.

Thanks Rob, much appreciated. Indeed, once under way it became a very compelling research project.