- Part 1 – Spica and the Tree of Life: The Moon and Abdul Alhazred

- Part 2 – Spica and the Tree of Life: Mercury and the Albatross

- Part 3 – Spica and the Tree of Life: Venus and the Moonchild

- Part 4: Spica and the Tree of Life: The Sun and the Alchemical Shadow

“The Substance” is a horror film starring actress Demi Moore playing the character of fitness instructor Elisabeth Sparkle. Sparkle is a reigning TV fitness model well-known for her long career of workout videos. However, the challenges of continuing her lifestyle and career—Sparkle has no family, spouse, or any mutual interests or hobbies other than being in the Hollywood spotlight—result in an inevitable end. A series of misfortunes and distractions leads to a car accident where Elisabeth finds herself in a hospital room, where she finally breaks down emotionally. The physician’s assistant, feeling pity for Elisabeth, offers her a second chance at life by smuggling a USB flash drive labelled “The Substance” into her jacket pocket without her noticing. She ends up finding it and throws it away. Initially reluctant to call the number stamped on the flash drive, Elisabeth fishes for the device from her trash can as her life spirals ever downward. Once hooked up to the TV, the device plays an ad for a mysterious health “supplement” guaranteed to solve her current problems. Elisabeth acquires “the substance” and proceeds in attempting to follow the precise directions for its usage.

What makes “the substance” a miracle drug is never explained except for showing what the drug does to Elisabeth. After receiving and preparing the dosage, Elisabeth injects it into her arm. Inside her body, the drug causes her tissue and bone structure—that is, all the cells in her body—to replicate into a younger version of Elisabeth, splitting and climbing out of the original Elisabeth’s back. This newer version—Sue—per the drug’s instructions, is only allowed to operate on her own for seven days at a time. During this time, Sue is required to sustain Elisabeth through weekly supplied interveinal feedings, as well as daily spinal injections administered by Sue to Elisabeth. The ordeal is completed by Sue, injecting nutrient-bagged food into Elisabeth’s arm, and injecting Elisabeth’s spinal fluid into herself. After seven days, as Elisabeth was nourished while remaining physically comatose for the entire week, Sue completes the week by transferring her own blood back into Elisabeth. Elisabeth comes back to life for the next seven days, taking on the caretaker role Sue had played the week before, along with nurturing herself back to health.

Initially, the arrangement seems to work. Sue is young, attractive, and shares all the prowess of a middle-aged woman’s knowledge, but embedded within the architecture of an alluring, sexually active woman in her early twenties. However, Sue soon takes over Elisabeth’s life. The customer-service representative for “The Substance” provides the disclaimer that it is crucial both individuals remember that they are One, that what one does affects the other; however, the guidance does not influence Sue nor her own need for attention. Care for Elisabeth is neglected. Laziness becomes resentfulness, which then becomes loathing.

Sue soon takes liberties to extend her own seven-day cycles, and she abuses Elisabeth’s body as the source of her own existence. These choices result in the physical atrophy of Elisabeth’s body. Soon enough, the bliss Sue follows in her selfish lifestyle becomes the misery and detriment Elisabeth exhibits in hers.

From the start, this story is somewhat like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: a creature is created, initially with hope and imagination, but instead reveals itself to be a monster. Yet, it is also like Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde: a chemical substance transforms one person into something entirely different. These themes in this film are prevalent. But the theme that grabbed my attention the most was how “The Substance’s” plot related to Oscar Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray. Sparknotes.com provides a good summary of the novel below:

In the stately London home of his aunt, Lady Brandon, the well-known artist Basil Hallward meets Dorian Gray. Dorian is a cultured, wealthy, and impossibly beautiful young man who immediately captures Basil’s artistic imagination. Dorian sits for several portraits, and Basil often depicts him as an ancient Greek hero or a mythological figure. When the novel opens, the artist is completing his first portrait of Dorian as he truly is, but, as he admits to his friend Lord Henry Wotton, the painting disappoints him because it reveals too much of his feeling for his subject. Lord Henry, a famous wit who enjoys scandalizing his friends by celebrating youth, beauty, and the selfish pursuit of pleasure, disagrees, claiming that the portrait is Basil’s masterpiece. Dorian arrives at the studio, and Basil reluctantly introduces him to Lord Henry, who he fears will have a damaging influence on the impressionable, young Dorian.

Basil’s fears are well founded; before the end of their first conversation, Lord Henry upsets Dorian with a speech about the transient nature of beauty and youth. Worried that these, his most impressive characteristics, are fading day by day, Dorian curses his portrait, which he believes will one day remind him of the beauty he will have lost. In a fit of distress, he pledges his soul if only the painting could bear the burden of age and infamy, allowing him to stay forever young. After Dorian’s outbursts, Lord Henry reaffirms his desire to own the portrait; however, Basil insists the portrait belongs to Dorian.

Over the next few weeks, Lord Henry’s influence over Dorian grows stronger. The youth becomes a disciple of the “new Hedonism” and proposes to live a life dedicated to the pursuit of pleasure. He falls in love with Sibyl Vane, a young actress who performs in a theater in London’s slums. He adores her acting; she, in turn, refers to him as “Prince Charming” and refuses to heed the warnings of her brother, James Vane, that Dorian is no good for her. Overcome by her emotions for Dorian, Sibyl decides that she can no longer act, wondering how she can pretend to love on the stage now that she has experienced the real thing. Dorian, who loves Sibyl because of her ability to act, cruelly breaks his engagement with her. After doing so, he returns home to notice that his face in Basil’s portrait of him has changed: it now sneers. Frightened that his wish for his likeness in the painting to bear the ill effects of his behavior has come true and that his sins will be recorded on the canvas, he resolves to make amends with Sibyl the next day. The following afternoon, however, Lord Henry brings news that Sibyl has killed herself. At Lord Henry’s urging, Dorian decides to consider her death a sort of artistic triumph—she personified tragedy—and to put the matter behind him. Meanwhile, Dorian hides his portrait in a remote upper room of his house, where no one other than he can watch its transformation.

Lord Henry gives Dorian a book that describes the wicked exploits of a nineteenth-century Frenchman; it becomes Dorian’s bible as he sinks ever deeper into a life of sin and corruption. He lives a life devoted to garnering new experiences and sensations with no regard for conventional standards of morality or the consequences of his actions. Eighteen years pass. Dorian’s reputation suffers in circles of polite London society, where rumors spread regarding his scandalous exploits. His peers nevertheless continue to accept him because he remains young and beautiful. The figure in the painting, however, grows increasingly wizened and hideous. On a dark, foggy night, Basil Hallward arrives at Dorian’s home to confront him about the rumors that plague his reputation. The two argue, and Dorian eventually offers Basil a look at his (Dorian’s) soul. He shows Basil the now-hideous portrait, and Hallward, horrified, begs him to repent. Dorian claims it is too late for penance and kills Basil in a fit of rage.

In order to dispose of the body, Dorian employs the help of an estranged friend, a doctor, whom he blackmails. The night after the murder, Dorian makes his way to an opium den, where he encounters James Vane, who attempts to avenge Sibyl’s death. Dorian escapes to his country estate. While entertaining guests, he notices James Vane peering in through a window, and he becomes wracked by fear and guilt. When a hunting party accidentally shoots and kills Vane, Dorian feels safe again. He resolves to amend his life but cannot muster the courage to confess his crimes, and the painting now reveals his supposed desire to repent for what it is—hypocrisy. In a fury, Dorian picks up the knife he used to stab Basil Hallward and attempts to destroy the painting. There is a crash, and his servants enter to find the portrait, unharmed, showing Dorian Gray as a beautiful young man. On the floor lies the body of their master—an old man, horribly wrinkled and disfigured, with a knife plunged into his heart.1

Film critic and contributor to RogerEbert.com, Monica Castillo, in her article about “The Substance,” describes just how and why I liken the film to Wilde’s novel: the nature of one’s own “shadow,” or unacknowledged fears and instincts deep within one’s psyche. Elisabeth is impulsively at the whims of her own shadow:

“The Substance” works as well as it does because of Moore’s unbridled performance as a woman struggling with self-hatred, society’s treatment of her, and a newfound dependency on a miracle drug. In one particularly heartbreaking scene, Elizabeth stands in front of a mirror, fussing over the final details of her makeup and outfit. Although she looks glamorous as anyone could hope to look, her face betrays a dissatisfied stare as she sees more flaws than beauty before her. It’s a ritual many of us might know too well as we stress over accessories and lip color in the hopes of looking fashionable, carefully adding or subtracting layers of clothes and jewelry to feel good in our own skin. Elizabeth is so displeased with her image, she aggressively wipes the deep shade of lipstick across her face and pulls off the fake lashes from her lids. She can’t see her own beauty, and that will upend her life. While it may feel like a cautionary tale for our times, the horrors at the heart of “The Substance” have been with us for many years, and the issues the movie uncovers are so much more than skin deep.2

While Dorian Gray delves into behaviors based on sinful desires, like lust and murder, Elisabeth serves as the older and withering reflection of Sue, who was acting in the same capacity as Dorian did towards his own portrait. They liken it to a gargoyle, an unsettling reminder that karmic consequences and accountability for mal behavior are not far off. And, like both, the youthful, false-appearance version of the Self ends up taking the life of the aged vessel, in question. In Elisabeth’s case, “the substance” serves the same purpose as the curse Dorian utters.

What do these two tales have to do with the Sun or the fixed star Spica? In Kabbalah, the Sun represents the sixth sephiroth of the Tree of Life: Tiphareth. Six is a number of balance and harmony. It remains in the core of the Tree and represents the heart of man. Aleister Crowley, the “Beast 666,” as described in the previous article (“Spica and the Tree of Life: Venus and the Moonchild”), like his Venus, Crowley also had his Sun conjunct Spica in his natal chart. The following individuals, summarized in this article, also all exhibit a natal Spica Sun:

- Oscar Wilde: author of The Picture of Dorian Gray

- Philosopher and author Frederick Nietzsche

- Superman creator and author Jerome “Jerry” Siegel

- Occultist and author Michael Aquino

When I was writing this article, I was amazed at how well historical alchemical literature corresponds with “escapist imagination” themes in these authors’ works—Nietzsche is a good example—and this essay will unravel this theme. From his childhood and later into adulthood, Nietzsche was often lost in his own head, daydreaming, letting his imagination wander. His father would play notes on the piano, bringing him back to reality.

A close friend and classmate of his—Paul Deussen—would later recall just how confused Friedrich’s sensibilities were. He later related an account of how, in February of 1865, Nietzsche was on a trip to nearby Cologne and made his way to a brothel. Finding himself suddenly in the company of several prostitutes well-gifted in the art of seduction, Nietzsche is said to have become almost paralyzed with feelings of inadequacy. Frozen under the charms of his newfound sirens, he was only able to come to his senses by staggering over to a nearby piano, where he proceeded to pound out several songs. He apparently remained at the keys for the rest of his time at the brothel until he felt well enough to walk out. Deussen would later claim that Nietzsche was a virgin when he went into that Cologne brothel that day, and he remained so when he walked out.3

There are two important concepts Nietzsche wrote about that tie his Spica influence with alchemical literature, as well as other Spica natives: his refusal to accept the nature of duality and opposites in consciousness (The Birth of Tragedy) and his concept of the Ubermensch or “Super man/Over man” (Thus Spoke Zarathustra).

Thus far we have considered the Apollonian and his antithesis, the Dionysian, as artistic powers, which burst forth from nature herself, without the mediation of the human artist, and in which her art-impulses are satisfied in the most immediate and direct way: first, as the pictorial world of dreams, the perfection of which has no connection whatever with the intellectual height or artistic culture of the unit man, and again, as drunken reality, which likewise does not heed the unit man, but even seeks to destroy the individual and redeem him by a mystic feeling of Oneness. Anent these immediate art-states of nature every artist is either an “imitator,” to wit, either an Apollonian, an artist in dreams, or a Dionysian, an artist in ecstasies, or finally—as for instance in Greek tragedy—an artist in both dreams and ecstasies: so we may perhaps picture him, as in his Dionysian drunkenness and mystical self-abnegation, lonesome and apart from the revelling choruses, he sinks down, and how now, through Apollonian dream-inspiration, his own state, i.e., his oneness with the primal source of the universe, reveals itself to him in a symbolical dream-picture.4

Author Mircea Eliade interviewed C. G. Jung in 1952, summarizing the nature of alchemy in psychology:

The great problem in psychology is the integration of opposites. One finds this everywhere and at every level. In Psychology and Alchemy, I had occasion to interest myself in the integration of Satan. For as long as Satan is not integrated, the world is not healed and man is not saved. But Satan represents evil, and how can evil be integrated? There is only one possibility: to assimilate it, that is to say, raise it to the level of consciousness. This is done by means of a very complicated symbolic process which is more or less identical with the psychological process of individuation. In alchemy this is called the conjunction of the two principles. As a matter of fact, alchemy actually takes up and carries on the work of Christianity. In the alchemical view, Christianity has saved man but not nature. The alchemist’s dream was to save the world in its totality: the philosopher’s stone was conceived as the filius macrocosmi, which saves the world, whereas Christ was the filius microcosmi, the savior of man alone. The ultimate aim of the alchemical opus is apokatastasis, cosmic salvation…Alchemy represents the projection of a drama both cosmic and spiritual in laboratory terms. The opus magnum had two aims: the rescue of the human soul and the salvation of the cosmos. What the alchemists called “matter” was in reality the [unconscious] self. The “soul of the world,” the anima mundi, which was identified with the spiritus mercurius, was imprisoned in matter. It is for this reason the alchemist believed in the truth of “matter,” because “matter” was actually their own psychic life. But it was question of freeing this “matter,” of saving it—in a word, of finding the philosopher’s stone, the corpus glorificationis.5

Nietzsche was interested in this integration—he was consumed not only by curiosity but also by an obsession with it.

Nietzsche felt that the bleak but realist views of Schopenhauer served as an incredible ‘mirror of reflection,’ which allowed him to view both the world around him as well as himself and his own actions more critically. Eschewing his drunken fraternity days, he began to focus solely on improving himself. He was serious about these efforts, in fact, that he began to keep a personal diary, in which he complied all of his ‘self-accusing lamentations.’ In other words, he ceaselessly criticized himself in search of improving his own faults.6

Continuing with Eliade’s interview with Jung on alchemy:

The work is difficult and strewn with obstacles; the alchemical opus is dangerous. Right at the beginning, you meet the “dragon,” the chthonic spirit, the “devil” or, as the alchemists called it, the “blackness,” the nigredo, and this encounter produces suffering. “Matter” suffers right up to the final disappearance of the blackness; in psychological terms, the soul finds itself in the throes of melancholy, locked in a struggle with the “shadow.” The mystery of the coniunctio, the central mystery of alchemy, aims precisely at the synthesis of opposites, the assimilation of the blackness, the integration of the devil. For the “awakened” Christian this is a very serious psychic experience, for it is a confrontation with his own “shadow,” with the blackness, the nigredo, which remains separate and can never be completely integrated into the human personality.

On the psychological level, all these symbols and beliefs are interdependent: it is always a question of struggling with evil, with Satan, and conquering it, that is to say assimilating it, integrating it into consciousness. In the language of the alchemists, matter suffers until the nigredo disappears, when the “dawn” (aurora) will be announced by the “peacock’s tail” (cauda pavonis), and a new day will break, the leukosis or albedo. But in this state of “whiteness” one does not live in the true sense of the word, it is sort of abstract, ideal state. In order to make it come alive it must have “blood,” it must have what the alchemists call the rubedo, the “redness” of life. Only the total experience of being can transform this ideal state of the albedo into a fully human mode of existence. Blood alone can reanimate a glorious state of consciousness in which the last trace of blackness is dissolved, in which the devil no longer has an autonomous existence but rejoins the profound unity of the psyche. Then the opum magnum is finished: the human soul is completed, integrated.7

Of course, like many immersed in attempting to integrate the psychological-alchemical opposites in their lives, insanity took its course. Nietzsche succumbed to the inner torment, like Elisabeth Sparkle and Dorian Gray, unable to integrate the opposites, succumbing to the instinctual drives and emotions of the psyche. For this reason, I remain convinced that the “escapist imagination” element of Spica is but a byproduct of Spica’s own alchemical role, that individuals with a planet conjunct Spica in their birth chart will experience a life where the integration of opposites, as a theme, will predominate. In Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche develops another interesting concept:

It was here that Nietzsche conceived of his famous Ubermensch idea or as it is translated into plain English, ‘Superman.’ Not to be confused with the comic book character who flies around in tights, Nietzsche’s superman was a caricature of the rare, gifted few who could help humanity rise to the next level of development. The concept of Ubermensch would later be appropriated by Adolf Hitler and his Nazi government in their efforts to purify the Aryan race and rid it of ‘inferior humans,’ or Untermenschen. This, despite the fact that Nietzsche himself was an outspoken critic of anti-semitism and even claimed to be ‘a pure-blooded Polish nobleman, without a single drop of bad blood, certain not German blood.’8

I believe Nietzsche was referring to individuals who took the alchemical opus magnum seriously as a practice, as his concept, even though nationalists stole the concept and repurposed it to fit their own needs. However, “Superman,” as designed by another Sun-Spica native, Jerry Siegel, was not far off as a caricature repurposed in a similar way.

Anthropologically speaking, the conceptualization of the “superhuman” comes along human self-perception. As one perceives his own existential condition, he is also able to mentally project that perception into the definition of its opposite: the superhuman. The superhuman is, then, the condition that differs from human, and that realistically could bring it to its negation and ultimate annihilation…unless, of course, the superhuman becomes the prototype of humanity’s individual aspirations and social gain. In the wake of the ancient cultures, superhumans are heroes and demigods with supernatural abilities. They do not kill monsters because it is “cool,” they do so because they make the world at man’s measure, keeping, at the same time, human beings within the rules established by the gods. In the modern era, the concept of the superhuman is completely overturned. In short, Nietzsche defines the ‘Ubermensch’ (Thus Spoke Zarathustra—1896) as the sole creator of a new set of values for humanity. He must be able to transcend the ancient concept of a god as the moral regulator for human behavior and determine new rules for all. Would he fail, nihilism will prevail. Nietzsche also states that the ‘Ubermensch’ is the goal humanity must aspire to. As “God is dead,” man remains as his own judge and jury, a role he cannot take if he does not reach a superhuman condition. The concept was so profound that the intellectuals of the beginning of the 20th century quickly took a position to promote or criticize the idea of the “super-man” while writers could not resist making it their own. George Bernard Shaw’s play, Man and Superman (1903), depicts a revolutionary man considering himself above human concerns, as he refuses the Victorian morality. James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) hints at the ‘Ubermensch’ in its first chapters, while Jack London’s Sea-Wolf (1904), Iron Hell (1908) and Martin Eden (1909) are a criticism to Nietzsche’s ‘superman’ concept, and promote a Darwinian depiction of exceptionally gifted persons as social drivers of change. Summarizing, while western society of the early 20th century was ready to accept characters (and role-models) that re-interpreted the heroes of ancient times, perhaps because they had been part of literature for a long time, or else because they were heroes of a different era, that same society was still deciding if it was ready to accept the more modern concept of the ‘superhuman.’ It was difficult to understand if Nietzsche’s ‘Ubermensch’ was ‘pros’ or ‘cons’ human society as it was known back then. Was he a destroyer or a savior? A hero or villain? Was he truly the Man of Tomorrow? And while scholars, writers, and intellectuals squabbled, a couple of teenagers from Cleveland, Ohio, solved the problem merging Hercules and Nietzsche and published a self-produced magazine, letting the majority of the human race democratically decide if they wanted the super-man or not.9

One thing about the character stands out to me: Superman—Kal-El from the planet Krypton—once his ship arrived in Smallville, Kansas, and he was adopted by Martha and Jonathan Kent, he began developing superpowers thanks to the nature of the yellow Sun of our solar system. The nature of the Sun in alchemical literature, as well as the prevalence of the role of the Sun in the literature of these Sun-Spica natal-conjoined individuals, is recurring in the literature of Spica-Sun natives.

But can we say the same about occultist Michael Aquino? Like Crowley with a Spica-Sun, Aquino, in his life, was drawn to the same occult elements, nearly walking in Crowley’s own footsteps. Aquino was Anton LaVey’s deputy in the Church of Satan, then moved on to create the Temple of Set. He retired as an Army Lieutenant Colonel in Psychological Operations—his merits as an occultist and Soldier are vast. He had numerous degrees, also receiving his Ph.D. He worked in the financial sector. However, he was also investigated for numerous child molestation charges in San Francisco and linked to a child prostitution ring. Like Wilde and Crowley, Aquino seemed to epitomize the Dionysian extreme, yet Siegel transferred these archetypal drives into his characters; Nietzsche wrestled with integrating opposites but was unsuccessful.

What do we make of this? While this analysis can be considered speculation, as to the inner psychological processes that occurred in these individuals as observed by the passages from these creatives’ own literature and life events, chair of the Jungian and Archetypal Studies specialization of the Depth Psychology program at Pacifica University Graduate Institute, Keiron Le Grice, in his own memoir, The Lion Will Become Man: Alchemy and the Dark Spirit in Nature—A Personal Encounter, provides clarity as to why I believe a Spica natal Sun is the archetype of alchemy and a spotlight on it.

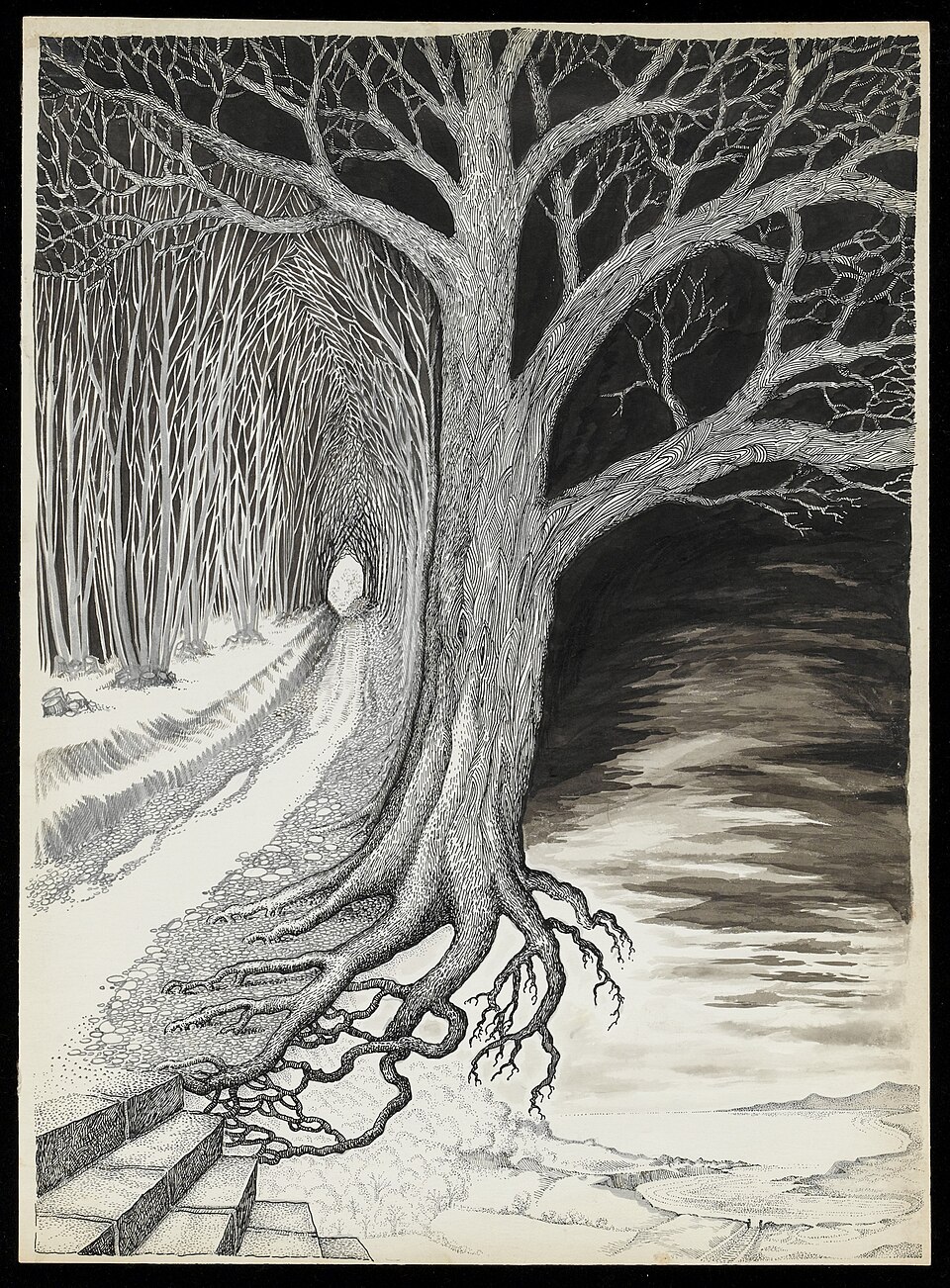

In the mythic scenes of the alchemical treatises, ego-consciousness is symbolized by Sol, the sun, suggesting the ‘light’ of consciousness and the capacity of self-reflective awareness to illuminate our experience. The symbolic connection is not peculiar to alchemy. A number of thinkers have depicted the rise of Western civilization and the rise of the modern ego-self using the analogy of the sun’s journey through the sky. In a glorious ascent from the night-time darkness below the horizon, the sun reaches its pinnacle, just as the ego emerges, over the course of our collective psychological history, to an apex of differentiation. The modern individual, the solar ego, comes to know acutely the experience of separateness—of its identity, will, judgment, and awareness—as it stands alone, the luminous center of its own world. The trajectory of egoic development—with the human being emphasizing its own will and estranged from the larger matric of cosmic or religious meaning—culminated, perhaps inevitably, in nihilism, with the purported loss of all meaning. This development was dramatically captured in 1882 by Friedrich Nietzsche’s proclamation of the ‘death of God,’ in The Gay Science, in words uttered by a ‘madman.’

But, with a keen sense of his own destiny and our collective future, Nietzsche also serves as the prophet of an impending descent in a critical moment of transition (‘the great noontide’) in the trajectory of the life course of the ego and of human civilization. Nietzsche has Zarathustra say to the sun: ‘I must descend into the depths: as you do at evening, when you go behind the sea and bring light to the underworld, too, superabundant star! Like you, I must go down.’ For as surely as night follows day, so the solar ego continues on its course, and thus begins its descent into the darkness of the underworld. The alchemical opus, I came to discover, describes this transformative underworld journey in extraordinary detail.

Essentially, alchemy, as Jung understood it, seeks to bring two different systems within the psyche—the daylight world of consciousness and the dark underworld of the archetypes and instincts—into an integrated relationship, although the initial coming together of these systems can often have volatile and disturbing consequences. In the alchemical texts, the two systems are symbolized by pairs of opposites: Sol and Luna, king and queen, and Adam and Eve. These pairs are different ways of depicting the basic duality of psychological life and the potential for the union of the separated opposites or psychic system in a culminating synthesis of a ‘sacred marriage,’ of masculine and feminine. Our primordial experience of the day sky and night sky, each with its own ruling light, Sol and Luna, partakes in this fundamental duality and interconnectedness of the two sides or systems of the psyche. This might be a projection of a psychological reality onto our experience of the world and the heaves or it might point, as I believe, to an underlying identity of the physical universe and the psyche. Either way, Sol, the sun, represents the ‘masculine’ spirit and the light of conscious awareness, attached to the ego; and Luna, the moon, symbolizes the ‘feminine’ principle and the lesser, softer, reflective and receptive light within the darkness of the unconscious.10

Consider the archetypal images that arise in the mind between reading the lyrics of Night Demon’s “Ancient Evil” from the “Spica and the Tree of Life: The Moon and Abdul Alhazred” and another heavy metal band, Satan, and their song “Burning Portrait,” an homage to Wilde’s novel. (Sidenote: both bands toured together in 2023; I saw them live in Boston.) Consider the archetype of the Spica Moon and the Spica Sun and how both song lyrics integrated seem to reflect the Dionysian literature of Wilde and Nietzsche, as well as “The Substance,” and the Apollonian left-brain models of consequences for sin.

Spica-Moon Dionysian archetype:

“Ancient Evil” by Night Demon

Long ago in a distant land

Lived a crazy Arab man

Cross his path, it’s likely you’d be dead

He wrote a book bound in human flesh

Told the secrets of Sumerian death

Crimson desert is where he laid his head

Can you hear Cthulhu’s call?

Monsters of death one and all

Satan’s will shall be done

High priest to The Great Old Ones

Ancient Evil (chorus)

No one knows the madness inside

To find the answer you must truly die

Darkness lurks deep in the heart of man

The answer is in the Necronomicon

The grimoire promises a new dawn

Embrace its power if you can11

Spica-Sun Apollonian archetype:

“Burning Portrait” by Satan: https://youtu.be/zJwXL7xfGJo.

In your mind hangs a picture of yourself

It’s the man that you wanted to be

There were times when you’d stop to admire

The fine strokes of a confident hand its honesty

Now you’ve covered it over

Now you can’t bear to look

You can’t stand to face up

To what you for took

Your portrait is burning, burning

Douse the fire now

Burning out of control

Yet you seem so invincible somehow

Once you were revered by statemen

And cardinals sought your advice

Your name was embossed on the lips of the great

And the good and the famous but oh what a price

Now the paint is corrupted

It’s consuming your mind

Devouring itself and each principle

You left behind

Your effigy’s burning, burning

Kill this fire now

Burning into your soul

Are you still invincible now?

Enslaved to the dark side of the mirror

From when there is no return

Bonded for the price of nothing dearer

Then a cause-celebre, you’d eventually spurn

The eyes of the portrait, they turn

Glaring at you as they burn

In the end, you were tempted away

From the path you had wanted to take

Such is life in the limelight

When you trade integrity for gold

You were warned Heaven’s sake

You had such good intentions

They just melted away

Like the paint on your picture

And now you must pay

Your portrait is burning, burning

Douse the fire now

Burning out of control

Burning, burning

Kill this fire now

Burning into your soul

You were never invincible12

There is a scene in “The Substance” where, in Elisabeth’s incredibly luxurious, open concept living room, the centerpiece is a portrait of Elisabeth. Before she begins the drug trial, during her own spiral downward, in a fit of rage, Elisabeth flings her drink glass at the painting of herself, smashing the glass on the figure’s right eye. This area of the portrait becomes damaged. When Sue begins to take over Elisabeth’s life, Sue drags the giant portrait off the wall, lugging it somewhere out of sight. It is later Elisabeth, fed up with Sue’s antics and escapades—Elisabeth also experiencing her own physical deformities from Sue’s negligence with “the substance,” in particular in that same area of her face where the glass smashed on the portrait—she lugs the portrait back to its rightful place on the wall, even though “the substance” has already taken a toll on her body and she is physically unfit to do so. This is telling because it is the left-brain hemisphere that operates the right half of the body, via Nietzsche:

And what then, physiologically speaking, is the meaning of that madness, out of which comic as well as tragic art has grown, the Dionysian madness? What? Perhaps madness is not necessarily the symptom of degeneration, of decline, of belated culture? Perhaps there are—a question for alienists—neuroses of health? of folk-youth and youthfulness? What does that synthesis of god and goat in the Satyr point to? What self-experience what “stress,” made the Greek think of the Dionysian reveller and primitive man as a satyr? And as regards the origin of the tragic chorus: perhaps there were endemic ecstasies in the eras when the Greek body bloomed and the Greek soul brimmed over with life? Visions and hallucinations, which took hold of entire communities, entire cult-assemblies? What if the Greeks in the very wealth of their youth had the will to be tragic and were pessimists? What if it was madness itself, to use a word of Plato’s, which brought the greatest blessings upon Hellas? And what if, on the other hand and conversely, at the very time of their dissolution and weakness, the Greeks became always more optimistic, more superficial, more histrionic, also more ardent for logic and the logicising of the world,—consequently at the same time more “cheerful” and more “scientific”?13

The relationship between the left-brain hemisphere to the Sun and the right-brain hemisphere to the Moon, as written about by Colin Wilson’s study of Robert Graves’ The White Goddess and the cult of Cybele and Atys, corresponds all of these fictional narratives about the inability to integrate the opposites in an individual’s psychology which results in the philosophy of crime. According to Wilson:

Crime can be understood only as a part of the total evolutionary pattern. Man developed his ‘divided consciousness’ as a means of survival. In a sense, he was better off as an animal, for the animal’s consciousness is simpler and richer. (We can gain some inkling of it from the effects of alcohol—that sudden feeling of warmth and reality.) But this instinctive consciousness has one major disadvantage; it is too narrow. It restricts us to the present moment. So man developed the left brain to escape this narrowness. It has the power of reaching beyond the present moment: the power of abstraction. And it does this by turning reality into symbols and ideas. The left brain is fundamentally a map-maker. This is man’s present position. In fact, he spends a large part of his early life at school, acquiring a ‘map’ of the world he lives in. Yet when he leaves school, his knowledge of the reality of that world is very patchy. And modern life is so complex and confusing that huge areas of the map are bound to remain unexplored and ‘unrealized’. A savage who has spent the same number of years hunting and fishing will admittedly have a narrower view of the world; but what he does know will have the genuine flavour of reality. In a sense, modern man seems to have made a very poor bargain. He has acquired a map, and not much else. The ‘map’ concept explains the problem of crime. A man whose actual acquaintance with the real world is fairly limited looks at his map and imagines he can see a number of short-cuts. Robbery is a short-cut to wealth. Rape is a short-cut to sexual fulfilment. Violence is a short-cut to getting his own way. Of course, each of these shortcuts has major disadvantages; but he is unaware of these until he tries them out in the real world. When he learned to use his mind, this ability to steer made him also the first truly creative and inventive creature. He has poured that narrow jet of energy into discovery and exploration. But the sheer force of the jet has meant that whenever it has been obstructed—or whenever men have lacked the self-discipline to control it—the result has been chaos and destruction.14

Wilson’s observations strongly fit with the theories of Julian Jaynes, Frank Heile, and Donald Hoffman:15

Consciousness is based on language and it goes beyond sense perception. To Bertrand Russell’s example of logical atomism, ‘I see a table,’ Jaynes replied, ‘I suggest Russell was not being conscious of the table, but of the argument he was writing about. He should have found a more ethologically valid example…such as…How can I afford alimony for another Lady Russell?’ He concluded, ‘such examples are consciousness in action.’ As for the bicameral mind, his second main hypothesis, he invoked new evidence that a third of all people experience auditory hallucinations. Congenital quadriplegics understand language and hear voices of gods, without ever having moved or spoken. In short, we continue to show artifacts of bicamerality. In the hypothesis of dating, he adds a weak form of the theory, dating consciousness from 12,000 B.C., assuming that both mentalities developed together and then the bicameral one was ‘sloughed off.’ The stronger form of the dating argument, the one he presented in the book, was that consciousness arose around 1200 B.C. Finally, his double brain hypothesis about hallucinations occurring in the right hemisphere and ‘heard’ by the left, could now be tested, he suggested, using cerebral glucography with positron emission tomography (PET) scans. Jaynes cited a study showing more glucose uptake occurred in the right hemisphere when a patient was hearing voices.16

Heile, a physicist from Stanford University, puts forth a theory of two categorically different modes of consciousness operating in parallel (simultaneously) within a single human mind. Calling them the Symbolic Consciousness and the Primary Consciousness, Heile sees these two seemingly independent categories of awareness coexisting within one individual human consciousness ’whole.’17

Using Hoffman’s approach we can see, at the top level of human cognitive activity, two minds operational as one self. Split-brain research supports this contention by noting that what is referred to as your mind is actually a blending of two distinct personalities, two architecturally separate conscious entities, likely inherited (’booted’) initially from the unique holonomic plasma energy signatures of your mother and father, blended into one new configuration (’you’) during the brief moments of procreative inception. Your left-hemispherical mind-avatar was seeded with a clone of your father’s electromagnetic plasma holonomic ’vibrations,’ while your right-hemispherical avatar was booted up with a clone of your mother’s plasma vibrations.18

Correspondences in the research of Jaynes, Heile, and Hoffman occur even to the effect of observing The Secret of the Golden Flower—a Chinese sacred book brought to the West by Richard Wilhelm. And as synchronicities of this nature as coined by C. G. Jung occur in oddly meaningful ways—Jung was drawn to this book and also Wilhelm—leading here to a full-circle occult influence via Edgar Cayce can be summed up from the Director of the Edgar Cayce’s Association for Research & Enlightenment (A.R.E.), John Van Auken (from his Edgar Cayce and the Secret of the Golden Flower: Ancient Taoism Way to Your True Self):

By the time I came across the Golden Flower teachings, I understood that ‘Heavenly Heart between the sun and moon’ was actually the place of my deeper mind and its view from behind my two eyes. This fit well with my study of ancient Egyptian wisdom in which the right eye represented the sun and was called the ‘eye of Ra,’ while the left represented the moon and was known as the ‘eye of Horus.’19

That is, Elisabeth smashed her image’s Eye of Ra, thus cursing her life to a disintegration of opposites in her psychological alchemy, by now only relying on the left (the Moon).

For a final takeaway, based on the video game Silent Hill—the film under the same name but with a storyline a little simpler than the game—is a narrative about a little girl from an abandoned West Virginia coal-mining town. The town is based on the real-life Centralia, Pennsylvania, where the coal fire burning under the town continues to this day. The little girl, adopted from an orphanage as a baby, begins to have dreams, sleepwalk, and paint pictures about Silent Hill. The adopted mother brings her to Silent Hill, where the town seems to exist in a liminal state: the abandoned version in real life and a dreamlike version that cycles through a hazy “reality” and a nightmarish one. The little girl also resembles another little girl considered a heretic by the local Christian cult because her own birth was nontraditional and considered “questionable” (no father or “secret” father). I mention that the game and film plots differ slightly, but the general theme of the film is that the previous young girl—not the adopted one—was burned by the cult fanatics after she was raped by the school janitor, presumably because she and her mother were both undesirable misfits. However, the little girl survives and is treated for third-degree burns in the neighboring hospital. As she also burns with revenge and retribution inside, her anger becomes her twin: either a malevolent spirit that sensed the girl’s anger and fed into her desire for judgement of the ones’ that wronged her, like a jinn; or, a splintered “other” of her own psyche that took on a life of its own. Regardless, between the traumatized, burned girl and the evil executor of the burned girl’s wishes, a child from the rape was born, who is the girl the family adopt from the orphanage.

There’s a purpose for this summary: in the film, when the adopted father discovers in a town’s archives the birth data for the burned girl and how her own image is identical to his adopted daughter, he’s puzzled at the age the burned girl would be today, roughly in her forties. In the scene, the following birth date is shown: November 11, 1974. Why is this date significant? On this date, the Moon was conjunct Spica in the afternoon. Here, yet another fictional narrative about the attempt to integrate one’s opposites in the theme of “escapist imagination.” Like “The Substance” and Dorian Gray, “Silent Hill” corresponds with the Spica-Moon’s theme in Night Demon’s “Ancient Evil.”

References

Castillo, Monica. “The Substance.” RogerEbert.com. https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/the-substance-movie-review.

Graves, Robert. The White Goddess: A Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1997. Kindle.

Hourly History. Friedrich Nietzsche: A Life from Beginning to End. Hourly History, 2022. Kindle.

Joye, Shelli Renee. Tantric Psychophysics: A Structural Map of Altered States and the Dynamics of Consciousness. Rochester: Inner Traditions, 2021. Kindle.

Le Grice, Keiron. The Lion Will Become Man. Chiron Publications, 2023. Print.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Birth of Tragedy. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/51356/51356-h/51356-h.htm.

Night Demon. Lyrics “Ancient Evil.” NightDemon.net. https://nightdemon.net/track/400439/ancient-evil.

Satan. Lyrics “Burning Portrait.” SatanMusic.com. https://www.satanmusic.com.

Sesselego, C. Jerry Siegel’s & Joe Shuster’s Science Fiction: The Advance Guard of Future Civilization. Blue Monkey Studio, 2020. Kindle.

Sparknotes.com “The Picture of Dorian Gray Full Book Summary.” Sparknotes.com. https://www.sparknotes.com/lit/doriangray/summary/.

Van Auken, John. Edgar Cayce and the Secret of the Golden Flower: Ancient Taoism Way to Your True Self. Virginia Beach: A.R.E., 2019. Kindle.

Wilson, Colin. A Criminal History of Mankind. New York: Diversion Books, 2015. Kindle.

Woodward, W. R, and Tower, J. F. “Julian Jaynes: Introducing His Life and Thought.” Reflections on the Dawn of Consciousness: Julian Jaynes’s Bicameral Mind Theory Revisited. Kuijesten, Marcel, ed. Julian Jaynes Society, 2013. Kindle.

Birth Data and Resources

Aquino, Michael, born October 16, 1946, San Francisco, California, US, at 12:34. Astro-Databank (https://www.astro.com/astro-databank/Aquino,_Michael). Source: Quoted birth chart/record (Rodden Rating: AA).

Nietzsche, Friedrich, born October 15, 1844, Rõcken, Germany, at 10:00. Astro-Databank (https://www.astro.com/astro-databank/Nietzsche,_Friedrich). Source: Bio/autobiography (Rodden Rating: B).

Siegel, Jerry, born October 17, 1914, Cleveland, Ohio, US, time unknown. All Famous (https://allfamous.org/astrology/jerry-siegel-19141017.html. Unknown source.

Wilde, Oscar, born October 16, 1854, Dublin, Ireland, at 03:00. Astro-Databank(https://www.astro.com/astro-databank/Wilde,_Oscar). Source: Original Source Not Known (Rodden Rating: C).

1 Sparknotes, “The Picture of Dorian Gray.”

2 Castillo, “The Substance.”

3 Hourly History, Friedrich Nietzsche, 16.

4 Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy.

5 Le Grice, 193.

6 Hourly History, Friedrich Nietzsche, 19.

7 Le Grice, 194.

8 Hourly History, Friedrich Nietzsche, 42.

9 Sesselego, 4-5.

10 Le Grice, 27-40.

11 Night Demon.

12 Satan.

13 Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy.

14 Wilson, The Criminal History of Mankind, 234.

15 Graves, The White Goddess, 56.

16 Woodward, Julian Jaynes, 70.

17 Joye, Tantric Psychophysics, 268.

18 Joye, Tantric Psychophysics, 265.

19 Van Auken, Edgar Cayce and the Secret of the Golden Flower, xxx.