1. Abstract

Did Plato lie about the Egyptian origin of the Atlantis story when he composed his famous dialogs Timaeus and Critias? Classicists say he had good reasons to make up a persuasive tale to prove an important point about ancient Greek society and politics. This, so-called, Noble Lie Thesis is the lens through which scholars of ancient Greece look when they read what Plato has Socrates, Critias, Timaeus, and Hermocrates say to each other about divine law and human corruption, cosmos and soul, Atlantis and Athens, and the rise and fall at the hands of the gods of these once mighty city states. In this article, I put the Noble Lie Thesis to a test by examining Egyptian cosmogonical texts for substantial congruences with Plato’s dialogs.

2. Introduction

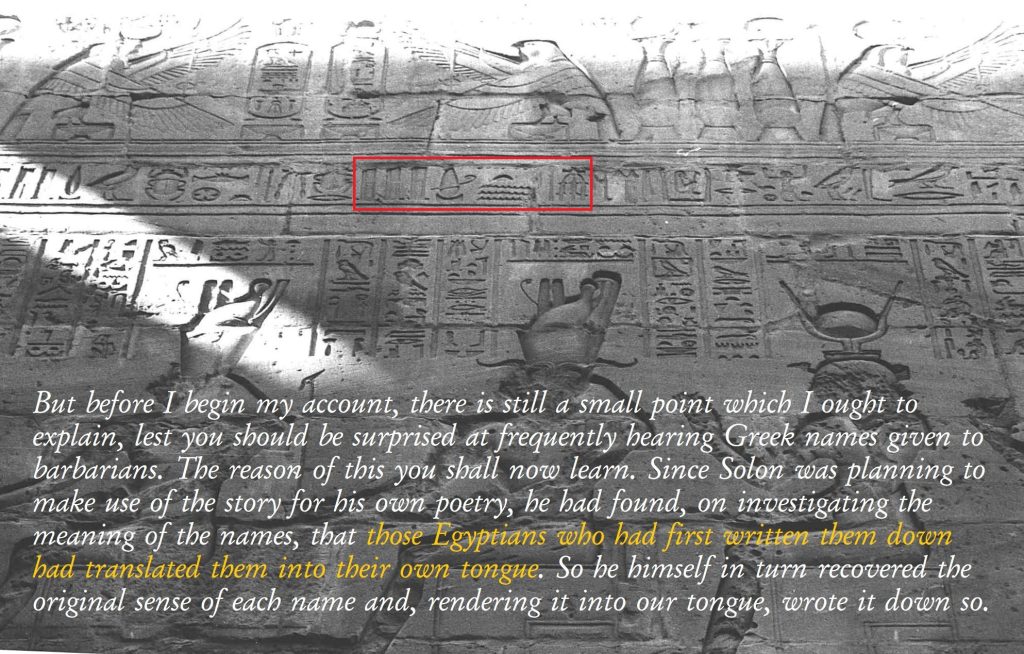

I am staring at a set of hieroglyphic symbols high up on the western wall of the Temple of Horus at Edfu in Upper Egypt. I can’t quite believe what I’m seeing. Is this the smoking gun that could single-handedly refute the skeptical view that Plato’s Island of Atlantis (Ἀτλαντίδος νήσου) was a fable, made up by the philosopher himself, and that his claim to an ancient Egyptian pedigree for the story is false?

How did I get here? A few years ago, I watched a now over 25-year-old film by Graham Hancock that kicked off my foray into the extensive archive of texts inscribed on the walls of the Temple of Horus at Edfu.2 The quest for a lost civilization whose memories and knowledge he believes are preserved in Egypt had taken Graham to this magnificent temple whose acres of walls are covered with tens of thousands of hieroglyphic symbols. On camera, as he makes his way through the temple, he recounts the story of survivors of a destroyed island who settled in Egypt to rebuild there what they had once built before on an island surrounded by an ocean, echoing a line from Plato’s Timaeus 25,a …“but that yonder is a real ocean, and the land surrounding it may most rightly be called, in the fullest and truest sense, a continent.”

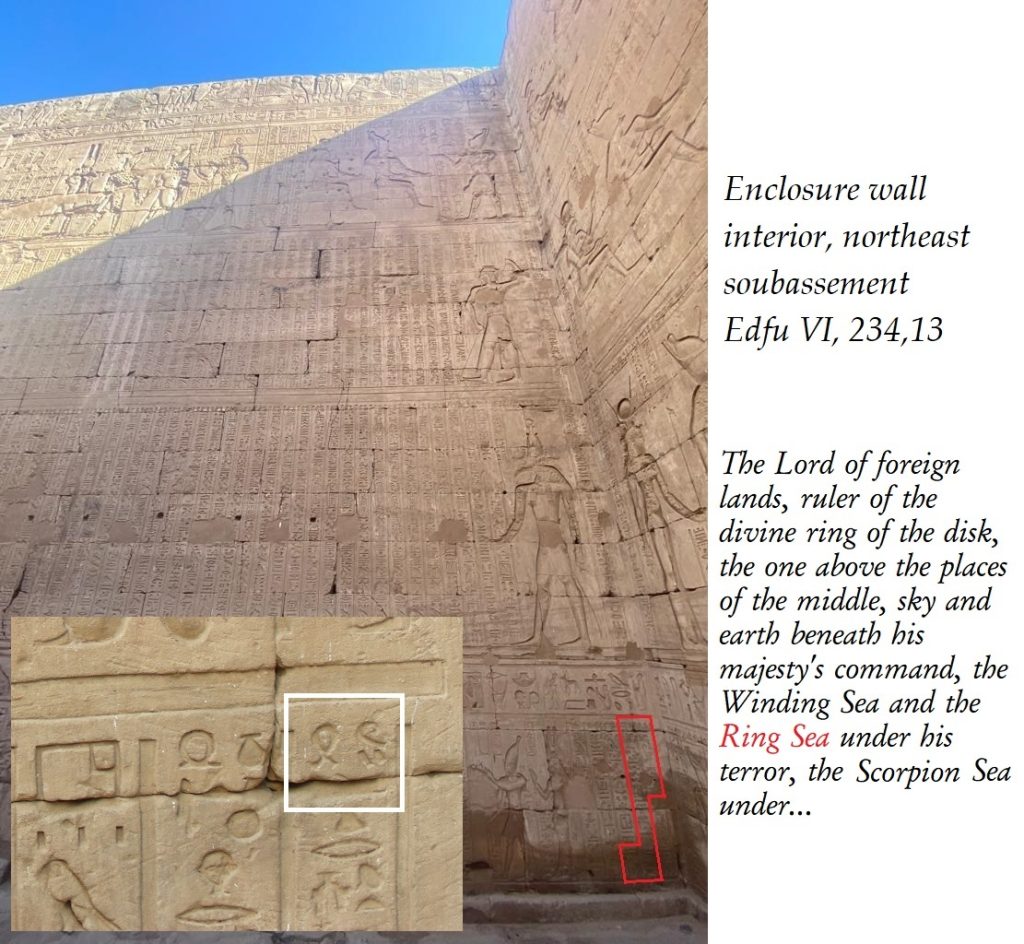

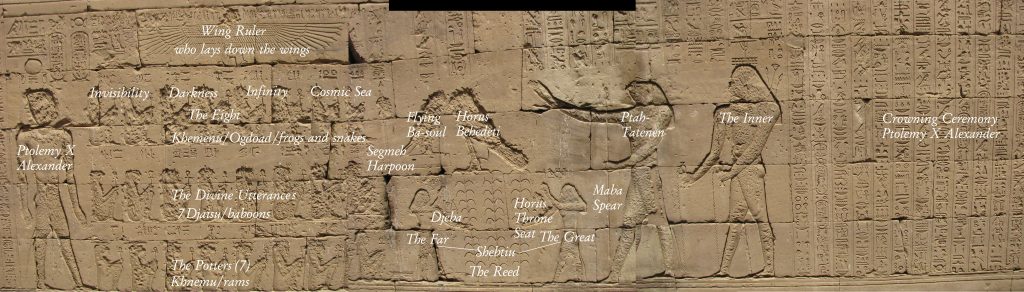

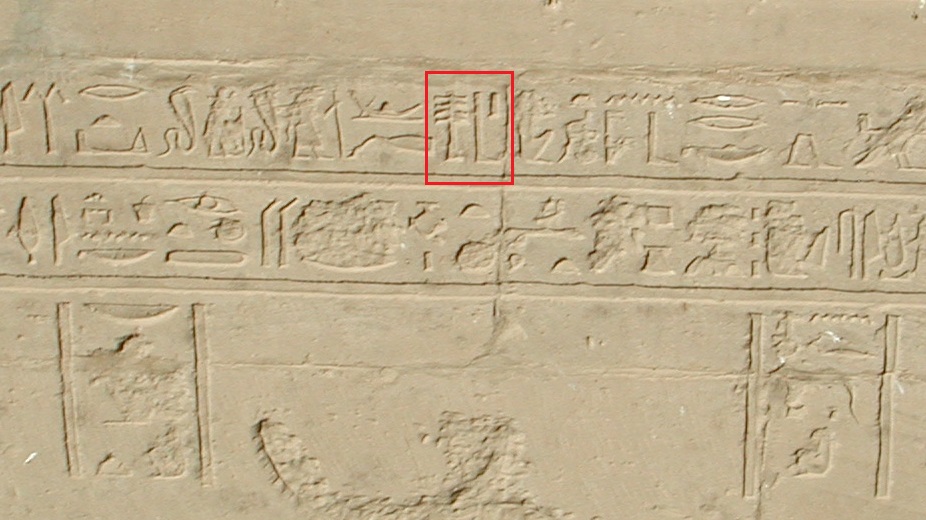

Figure 1: The dominion of Horus includes a Ring Sea (šn wr). Images courtesy of Sohaila Hussein and the German Edfu Project; modified with framed highlights.

In his book Magicians of the Gods, Graham draws a parallel between this story and what 4th Century BC Greek philosopher Plato has Critias, one of the four protagonists in his dialogs, tell Socrates happened to Atlantis—a story claimed to have been passed down from the Athenian statesman and lawmaker Solon who learned it from an Egyptian priest.

Here’s a brief synopsis of the story as we have it from Plato:

Atlantis was once a splendidly rich island in the Atlantic Ocean originally allotted to Poseidon when the gods divided up control of Earth. When Poseidon’s half-human heirs trade their inborn, divine nobility for their likewise inherited human frailty of being corrupted by material want, the gods punish them with a great flood. Atlantis and its people drown in the sea. The Atlanteans, according to Critias, were an imperialistic sea power once in an epic war with Athens. Plato has Critias tell this story to Socrates to indulge his theory of a planned and perfect state in which the military class is separated and shielded from material influences. The point of the story is to prove that this perfect society can prevail against any enemy whose army is corrupted no matter how powerful.

Through the lens of British Egyptologist Eve A. E. Reymond’s 1969 interpretation of the mythical origin of the Egyptian temple, Graham recognizes the same story at Edfu, together with its sequel: There were survivors. Some of them ended up in Egypt and became the mythical founder gods of the three cosmogonies in that ancient nation’s creation mythology. Their knowledge and know-how of architecture and astronomy, for example, became imbued into the ancient monuments in Egypt. They leave a lasting record of a forgotten chapter in human history, and a warning to posterity.

But did these events really happen or did Plato invent them for a good cause, a cause to benefit an Athens that during the prior century had fought two wars anything but glorious: the Persian and the Peloponnesian Wars. Both were won not by nobility and virtuous conduct, but by treason and treachery. Thus, the stakes were high for Plato to convince his fellow citizens to embrace a societal structure that could shield the army from corruption. Would he be willing to deploy a literary device to make the theory stick? Would he make up the proof that such a society is superior? Most, if not all, classicists would say ‘yes.’

That device was called a Noble Lie.3 Plato himself has Socrates mention it to Plato’s brother Glaucon in his older Republic (414c) as a “sort of Phoenician tale,” Seaman’s Yarn, in other words, used as a didactic ploy to shape the young minds of Athens’ future guardians. You could say ‘way to shoot yourself in the foot, Plato,’ or you could say ‘at least he was being honest about lying.’ Regardless, this confession tainted all those of his writings that he presented as ostensibly historical.

Indeed, if he deployed the Noble Lie device in Timaeus and Critias, he certainly tried to hide the lie by making the story as detailed, and hence as plausible, as possible, and by attributing it to the quintessential record keepers of his time, the ancient Egyptians. This, in essence, is what classicists and historians believe. They believe Atlantis is fiction because the story was told to make a point that could not in fact have been made using a true history that never was. The Noble Lie Thesis, in its extreme version, proposes that everything Critias tells Socrates, Timaeus, and Hermocrates is fiction, even their meeting to have had these dialogs.

Most importantly, some scholars also believe that Plato lied about the Egyptian origin of the story. To cover up the lie and fake it as truth, he deceivingly sourced it to the expert archivists of his time, the Egyptians, delivered to Athens by one of her most legendary and beloved heroes: Solon. The Egyptians allegedly had written records going back to nine thousand years before Solon’s visit to Egypt (i.e., to around 9560 BC), when the gods destroyed Atlantis and Athens. Their own recorded history, so tells Solon’s alleged source, a priest of the Temple of Neith at Sais in the Delta, began a thousand years later, which, if true, would be sometime between 9000 and 8000 BC.

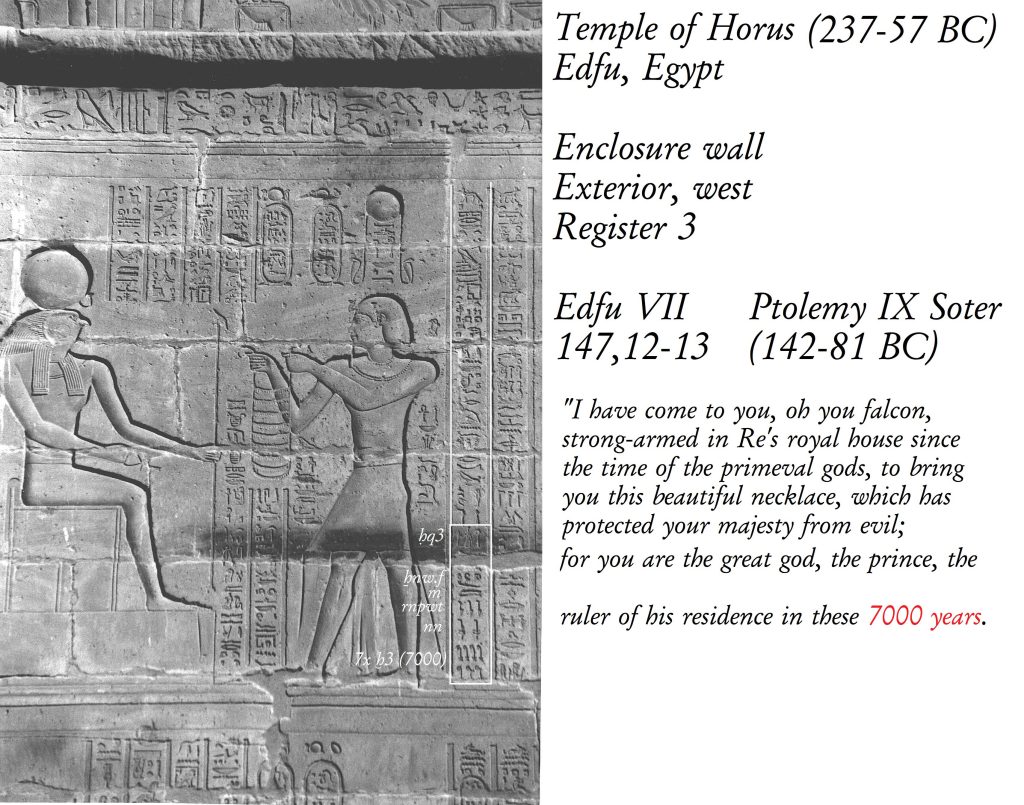

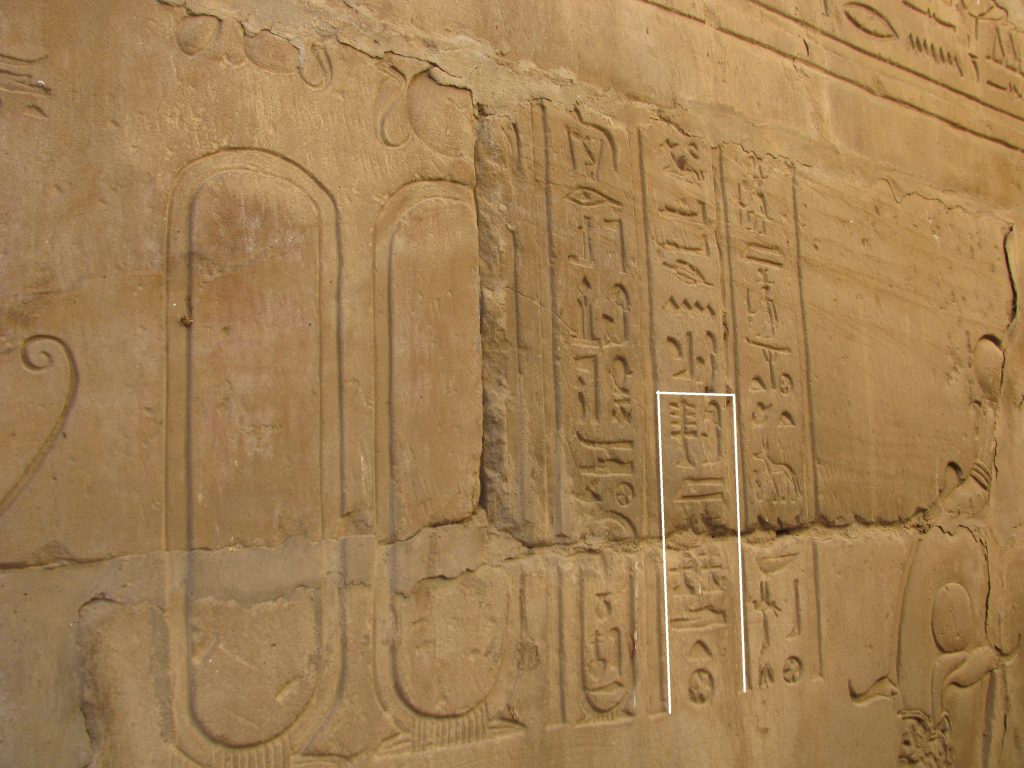

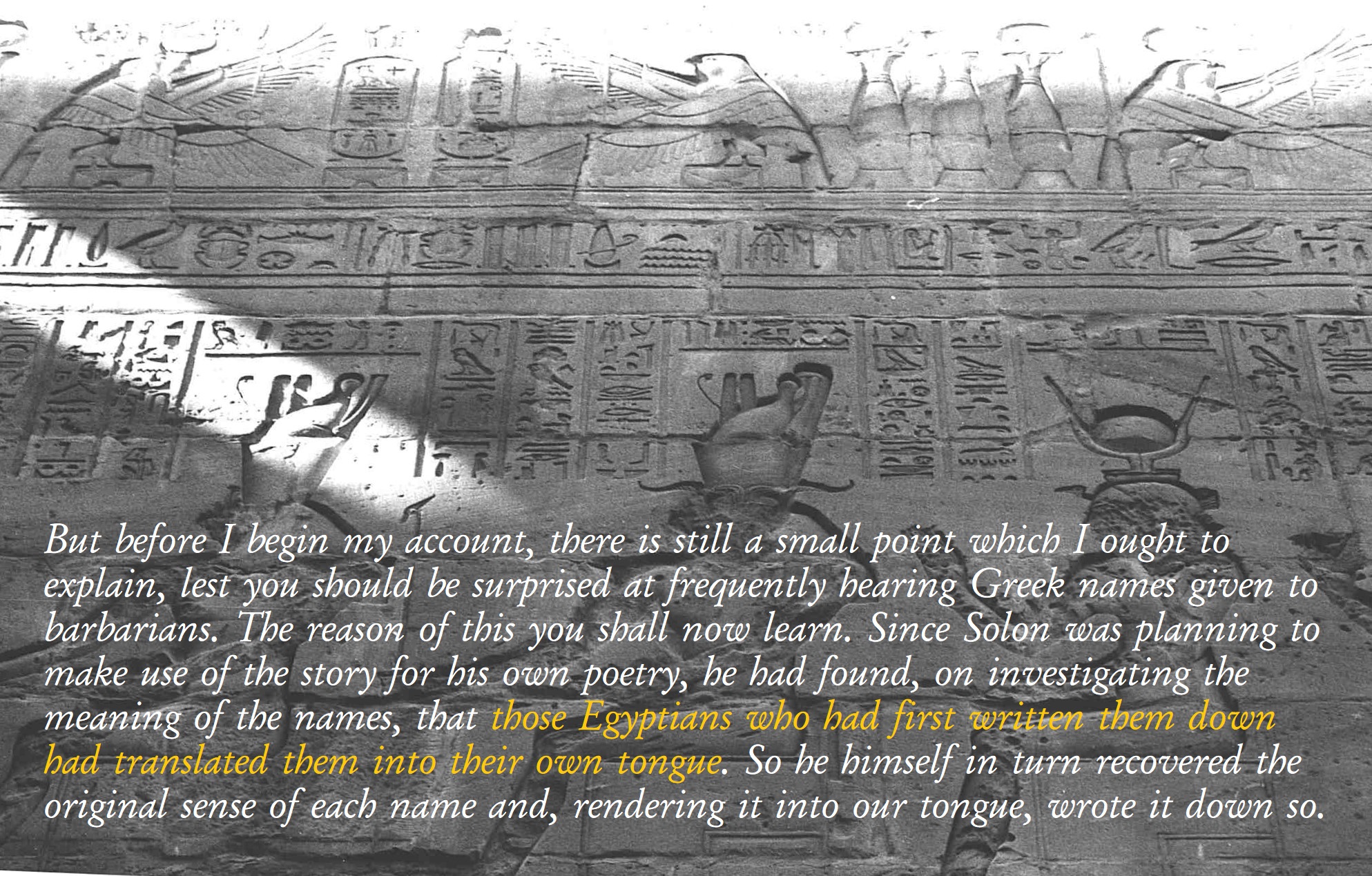

Figure 2: The necklace offering scene where the age of Horus’ rule is said to be seven thousand years. Modified photo courtesy of Émile Chassinat and the German Edfu Project. English translation from original German with transliteration (framed in white) by Dieter Kurth and the German Edfu Project.

An inscription on the exterior of the enclosure of the Edfu Temple (Figure 2) corroborates what Plato claims here through his proxy Critias. Horus’ rule is said to have begun seven thousand years before the original texts transcribed by the Ptolemaic scribes onto the temple walls were composed. Forensic, linguistic evidence from the redacted copies that these Edfu Temple inscription represent points to a terminus ante quem that coincides with the last use of authentic Middle Egyptian4—in contrast to a later made-to-look-old style called Traditional Egyptian—until approximately 1500 BC, or the beginning of the New Kingdom of ancient Egypt.

To give you an analogous, even more extreme example of such cursive, redacted original text on papyrus, of which both the age of the original text and the redaction are known to high degree, I cite a Demotic papyrus called Bodlean MS. Egypt. a. 3(P). This was discovered by retired Professor of Egyptology at University of Oxford, Mark Smith (Smith 2019). The text contains Pyramid Text utterances 25 and 32. The redactions, for example, involved changing the Old Kingdom Egyptian demonstrative pronouns to those used in Demotic. Remarkably, Smith even figured the date, to within one year, when this was done: During the middle of the reign of the Roman emperor Augustus who reigned from 30 BC to 14 AD. The difference in age of the Old Egyptian original and the Demotic redactions is therefore circa two thousand four hundred years. By analogy, the Edfu Texts come from originals written in Middle Egyptian that were redacted during the mid to late Ptolemaic era, circa 200-100 BC (Kurth 2009, pp. 6-7).

Graham believes that what is written at Edfu is indeed a body of history that is much older than the Egypt of the Ptolemies. He believes that these mythical texts, and what is known of Earth’s geological past contradict the claims that Plato lied. He recognizes in the Edfu Texts the story of what happened after this epic war of two opponents, after Atlantis and Athens were sunk by the sea and the Earth. What has been preserved of Critias is truncated at the end. The entire dialog with Hermocrates is missing. We therefore do not know how Plato ended the dialogs. But according to Graham, the missing end, Critias’ Sequel if you will, is recorded at the Edfu Temple, within a sea of hieroglyphic symbols that have only very recently been fully translated.

A couple of years ago, I casually asked Graham if he had any plans to return to Egypt. It might be difficult, was the reply. He had recently been denied filming permission there with the reason given being specifically his suggestion that the Atlantis story has a counterpart at Edfu. At this time, I was fully immersed in the language of the Pyramid Texts. I was interested not only in the writing itself, but also in how the writing was laid out inside their oldest and the most well-preserved sanctuary: The Pyramid of Unas, a king of the Fifth Dynasty, at Saqqara—about 20 kilometers south of the world-renowned Great Pyramid of Giza. Apart from the main theme that transpires from the general sequence of the Pyramid Text utterances, as proposed by since-retired Brown University Egyptologist James P. Allen, it turns out that the specific placement of short invocative phrases at certain positions of the interior architecture creates a previously unrecognized second theme.

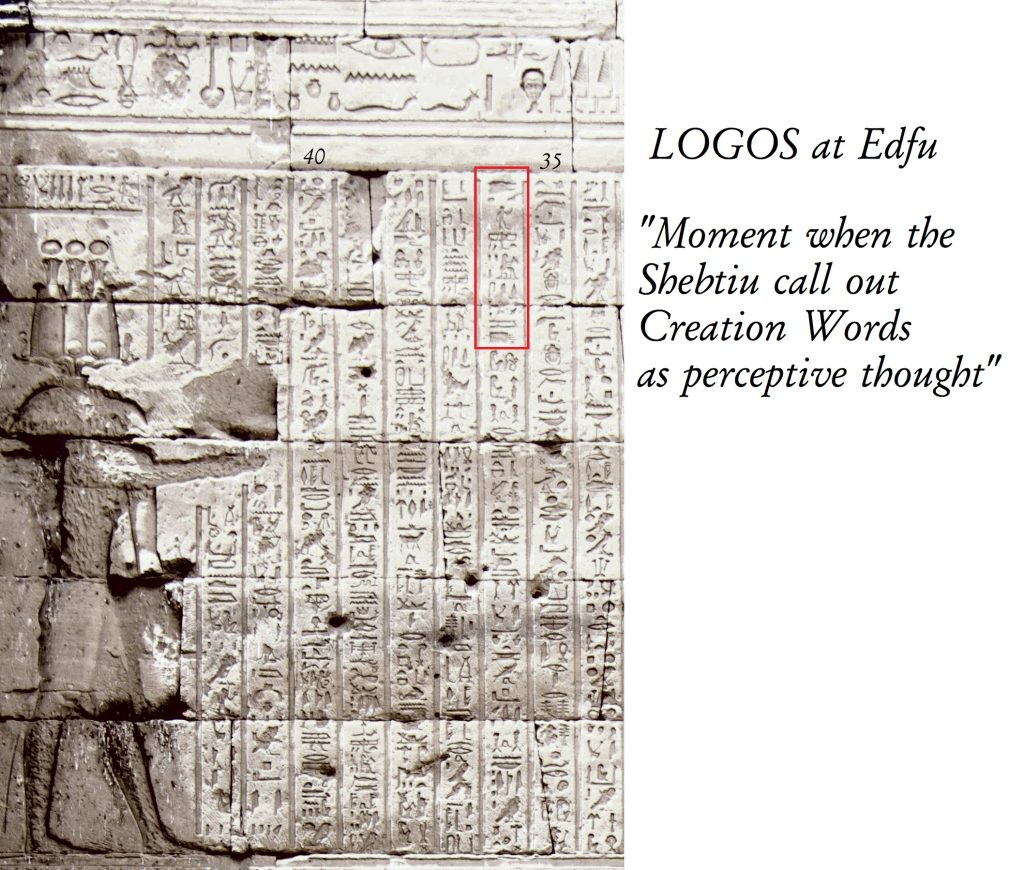

For example, together with Robert Neyland, I discovered that the antechamber, also known as the Horizon-Chamber (Akhet), textually simulates the then quintessential symbol of the horizon: the Great Sphinx statue at Giza. We discovered how the scribes used HEKA, a type of phonetic mimicry to invocate ethereal entities in the afterlife. These spiritual essences uttered (“ḥw”) into existence required knowledge of magic via a perceptive skill (called “sj3“) Unas in the afterlife acquired from a divine scroll called the Scroll of God after emerging from the lotus on the Island of Fire. This imagery belongs to Egypt’s oldest cosmogony from the City of Thoth, Hermopolis Magna. HEKA was to the Egyptians, we realized, what LOGOS is to the three Abrahamic religions: the manner with which God created.

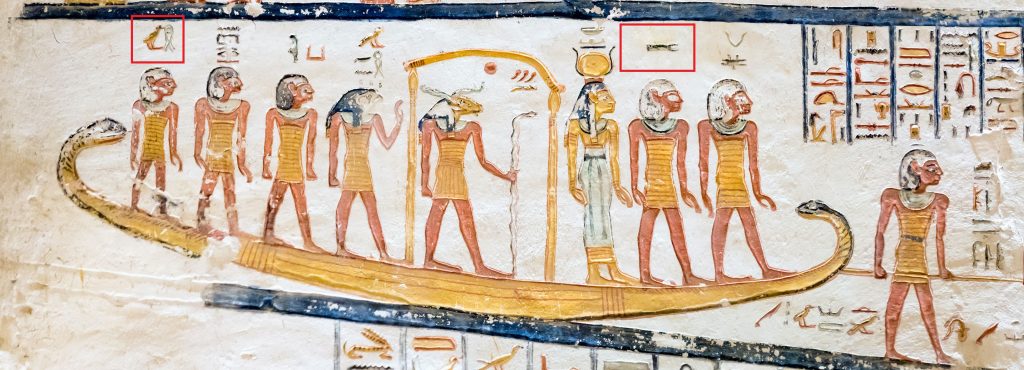

Figure 3: sj3 perception at the prow and ḥw utterance on the stern of the boat of Khnum-Re in the netherworld. Image from KV9 courtesy of Manna Nader; modified with red frames.

We also looked at the astronomy encoded in the utterances, their textual mentions as they related to the cardinal directions projected through the wall of the pyramid and into the sky. It was at this time that I had begun to tackle the writing at Edfu to see firsthand the creation story told on the temple walls. I had contacted the chief of the German Edfu Project, now retired Hamburg University professor Dr. phil. Dieter Kurth to buy his Introduction into Ptolemaic.

Figure 4: The LOGOS formula in the creation story written at the Temple of Horus. Image courtesy of Charles Lancelotta; modified.

It was against this backdrop, in a further conversation with Graham, that I offered to look more deeply into the Atlantis-Edfu connection, which by then, as a result of Graham’s work (Hancock and Bauval 1996, Chapter 12), had already become a bone of contention with skeptical archaeologists.

I began by reading the relevant chapter in Magicians of the Gods, Chapter 9, The Island of the KA. There, Graham mentions a certain Welsh Egyptologist by the name of John Gwyn Griffiths who long ago asked a more modest question about Atlantis: Did Plato truly get the story from Egypt, whether it is true or not? He compared the Middle Kingdom wisdom literature classic The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor with the parts in Critias that describe the Island of Atlantis and indeed found some interesting congruences. When Griffith published his analysis in 1985, Dieter Kurth was only in the preliminary stage of assembling what would a year later officially become the German Edfu Project.

This is when I became convinced that another look at this problem may be justified. The only way to falsify the basic version of the Noble Lie Thesis is to discover a real Atlantis under the sea. This was clearly beyond my abilities to put to a test. However, if the recently translated Edfu texts substantially corroborate Plato’s Greek creation myth and Atlantis story told in Timaeus and Critias, and these themes predate the philosopher’s time, the Noble Lie Thesis in its extreme version—to put it in logical terms, the null hypothesis that everything is a lie and there is no truth in Plato’s dialogs—falls.

To be sure, the evidence that makes the Noble Lie Thesis, even in its extreme version, probable, and thus plausible, is formidable. I recommend two references to get a taste of what one is up against: 1) a radio program called In our Time5 featuring Professor of Classics at Durham University Edith Hall, Emeritus Professor of Ancient Thought at the University of Exeter, Christopher Gill, and Angie Hobbs, Professor of Public Understanding of Philosophy, University of Sheffield, and 2) an as even-handed as can be article by Thomas K. Johansen from the Center for Hellenic Studies at the University of Bristol entitled Truth, Lies and History in Plato’s Timaeus-Critias.

There is no point trying to address, let alone argue against, each item in this extensive list of evidence supporting the Noble Lie Thesis because the thesis categorically falls on all these individual pieces of circumstantial evidence with positive proof that Plato didn’t lie about the Egyptian origin of the story. I will not quibble here. I concede that the circumstantial, indirect case for the Noble Lie Thesis is well supported, but it remains subject to falsification by direct evidence that outweighs it. Weighing evidence is a difficult exercise, but direct evidence generally weighs more than indirect evidence.

After reviewing the several arguments in favor of the thesis, you will understand why most, if not all historians and classicists believe in it. But when new evidence comes to light, a review of the old paradigm is in order. Neither objective probability, nor subjective plausibility, which is often influenced by biases, are strict, scientific standards. In science, a model stands until it is proven to be impossible by demonstrating an observation that contradicts it. A reasonable motivation, in any event, to put the Noble Lie Thesis to another test is based on two facts: The Edfu texts have only recently been thoroughly surveyed and fully translated, albeit into German, and most historians and classicists haven’t been able to review them.

I’m sure you see now where this is going to go. Is it possible that classicists have succumbed to a generalization bias? Have they been presumptive in believing that Plato made up the content of his dialogs based on his earlier works where it is written that a lie for good cause is justified? This is not the kind of question to attract many scholars once consensus is in place. There are reputational risks to them among other reasons to forgo such review like the risk of wasting time and research funds. It takes an outsider with a special set of circumstances and serendipity to make a new opening, reduce these risks, and broker a dialog between experts who may not be comparing their up-to-date notes. This is why I suggested to Graham that I should look into the Noble Lie Thesis.

I speak fluent German and English. I am a trained medical doctor (M.D.) and scientist (Ph.D.). I have acquired efficient learning skills and use the scientific method in my practice every day. I have a working knowledge of hieroglyphic ancient Egyptian, and I have developed a working relationship with the world’s topmost expert in Ptolemaic Egyptian, who has since also become my friend: We call each other Dieter and Manu, respectively, a big deal in Germany more so than in the United States where I live.

However, I am neither a credentialled Egyptologist, nor classicist, nor historian: This is my first disclaimer. My shortcoming, for example, is that I do not have a scholar’s command of the entirety of the vast literature on ancient Greek writings and history, nor am I an expert in Ptolemaic hieroglyphic, an exceedingly difficult phase of Egyptian. In countless hours of studying, I have acquired a working knowledge of it, not to unduly minimize this accomplishment either. But since I started to learn hieroglyphic, I have come to realize that there will always be limits to my ability to penetrate the many nuances and details of this language. As in Medicine, there are subspecialized Egyptologists like those few who focus on the forensic, linguistic details of the different language phases in ancient Egypt. Expertise requires years of experience with ancient texts I do not have. I had to rely on these scholars’ publications and take them at face value. I could not base my examination on my own interpretations of Plato’s writing, or my own interpretation of the relevant Edfu texts. I had to read them as they have been read by Dieter Kurth and his team. This is my second disclaimer.

Dieter Kurth is a subspecialized Egyptologist. He is probably one of only a handful of people alive today who can walk up to a wall of a Greco-Roman era Egyptian temple like the Edfu Temple and read much of it off like a billboard. Once in his office, he demonstrated this to me to my sheer amazement. I know it may be hard to imagine that reading the Pyramid Texts in this manner is much easier by comparison, but to me it is. They were written with a much smaller set of symbols, fewer word signs, and more distinct sound-to-symbol correspondence. At Edfu, a bewildering zoo of never-before used symbols confronts you.

Dieter has spent nearly 40 years advancing the work begun by his predecessor, the French Egyptologist Émile Chassinat, over a similar timespan about a century ago. Leading the German Edfu Project, Dieter used state of the art cross referencing tools, and a new photographic survey to correct old errors, more accurately reproduced the hieroglyphs, transliterated them, and provided a compelling translation of most of what is written on the staggering total wall surface of the temple. He has also published a grammar and a lexicon, an architectural analysis, and is still distilling various take-aways from this monumental volume of texts.

About a year ago, I offered to translate into English Dieter’s German translation of one of the most difficult passages from the Edfu temple—a passage that contains the creation myth. My plan was to use Dieter’s transliterations, his German translation, and the Edfu Project’s close-up photos of the original hieroglyphic text on the uppermost register of the inner face of the enclosure wall near the northwest corner to generate an as originalist version in English as possible. I have recently published this translation so that others can now avail themselves of these incredible text columns without having to learn either hieroglyphic or German.6

Here then is my third disclaimer: In this article, I do not speak for, or on behalf of Dieter Kurth. He may disagree with me on any, and all of what I am about to write. I can, however, refer you to an upcoming paper he had me read last year, in which he tackles the difficult task of defining how the ancient Egyptians may have developed a philosophical school of thought quite different from that of the ancient Greeks. In this article (Kurth 2024) there are a few fascinating metaphysical congruences between Egypt and Greece, including with Plato, but Dieter ultimately concludes that the fundamental approach to understanding cosmogony, religion, and life after death in both cultures was different: Ancient Greek thinking was about narrowing down the terms used to build a philosophical theory by defining them, while analogous terms in ancient Egypt were allowed to stay open to alternative interpretations, thus not excluding anything.

I think this is a great insight, especially useful when comparing how the ancient Greeks and Egyptians sought to answer the same big questions we still debate today. It means to me that the linguistic imprecisions one encounters in religious or cosmogonical Egyptian texts may indeed serve better to communicate those aspects observed in nature, which could not be collapsed into a deterministic state.

The question I address here, however, is not about sporadic congruences. Rather, the question is did Plato substantially and intentionally—not sporadically, casually, unwittingly, or randomly— lean on Egyptian stories to compose his dialogs, as he himself informs us through his protagonist Critias at the outset. The Atlantis story came from Solon, and Solon brought it to Greece from Egypt. Is that part true history? The Greek cosmogony presented by the philosopher Timaeus of Locri in Plato’s Timaeus introduces a reasoning creator god7 who intellectually perceives, then fashions a living, soulful, and infinitely time-ticking cosmos together with its first generation of gods from elemental matter as a copy of a perpetual, timeless, primeval, living creature cosmos. Did Plato adopt key themes in this cosmogony from Egypt?

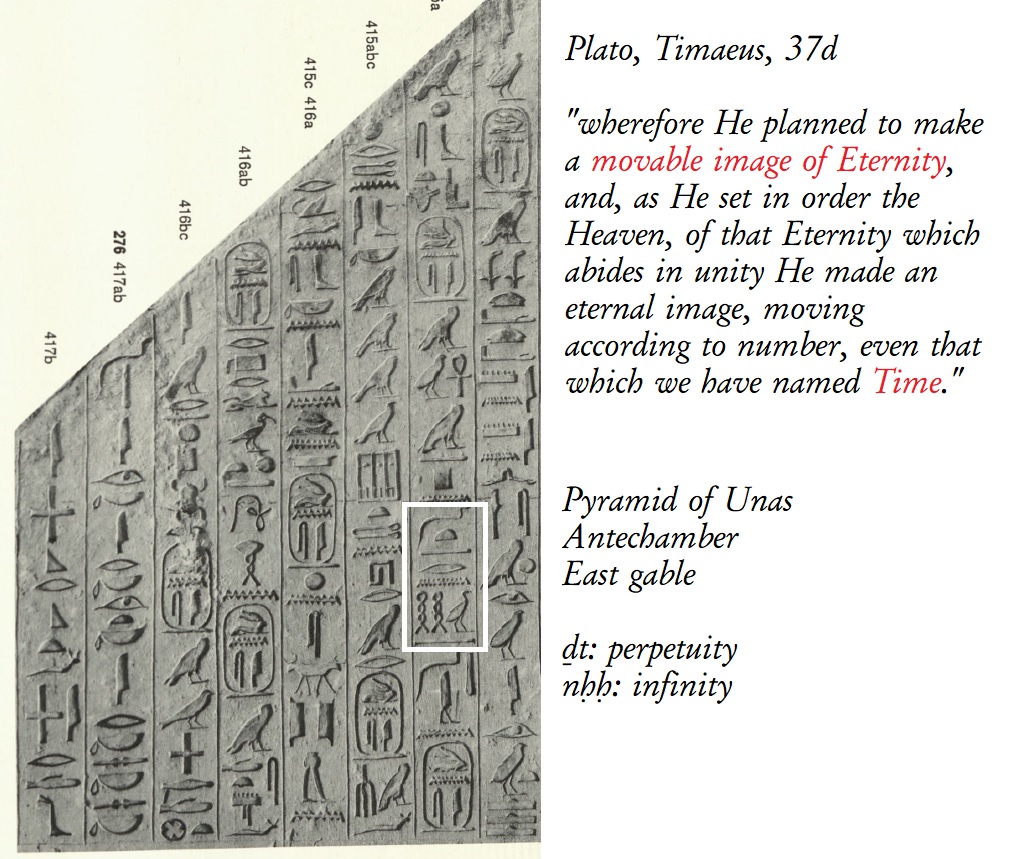

Figure 5: The dual concept of eternity In Plato and the Pyramid Texts. Image from Piankoff 1968; modified.8

With the English translation of the relevant Edfu text in the public domain now, I can proceed and put the Noble Lie Thesis to a test. I can look for substantial, i.e. structural story congruences in Plato’s dialogs and at Edfu, as well as in older texts such as the Pyramid Texts. Even if it can be shown that Plato didn’t lie about receiving an Egyptian tale from Solon does not, by necessity, make the tale true history. It could be an Egyptian “lie,” only falsifiable with physical proof of a sunken city that looks like Plato’s Atlantis. I must leave that question for others to investigate.

With that rationale in mind, let me take you to the Creation Story at Edfu to show you that the chief creation myth recorded there is really a story with two chapters, connected by a few key common actors; These two chapters, if you will, are the Cosmogony of Hermopolis followed by the Cosmogony of Memphis. The basic elements of both, including their connection, come from the Pyramid Texts as recorded in the antechamber of the Pyramid of Unas at Saqqara, Egypt.

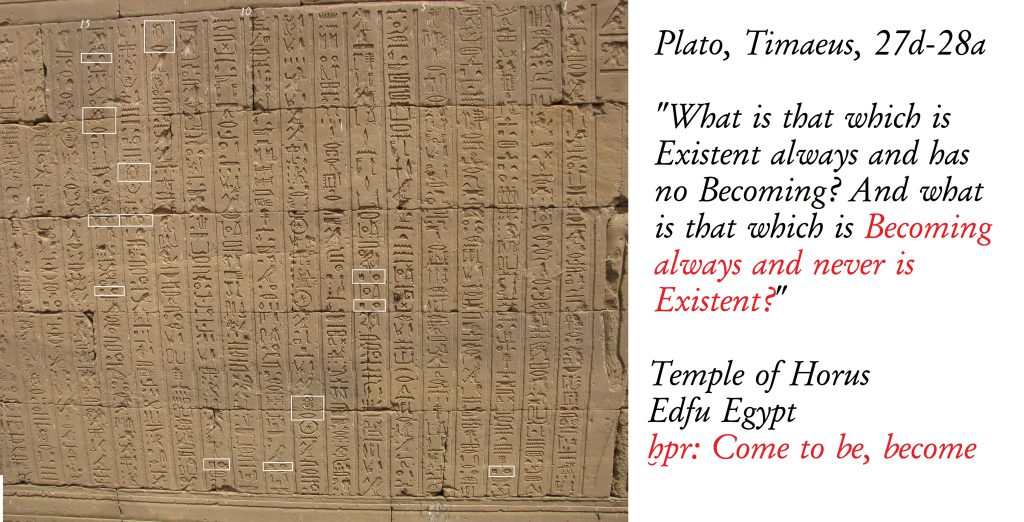

Figure 6: Instances (13) of “come(s) to be” mentioned during Part III of the creation story during the creation of the KA-realm. In Timaeus 29e, Plato refers to “the supreme originating principle of Becoming and the Cosmos.” Image composite based on images courtesy of the German Edfu Project and Dieter Kurth; modified with white frames to highlight the word ḫpr.

3. The Evidence

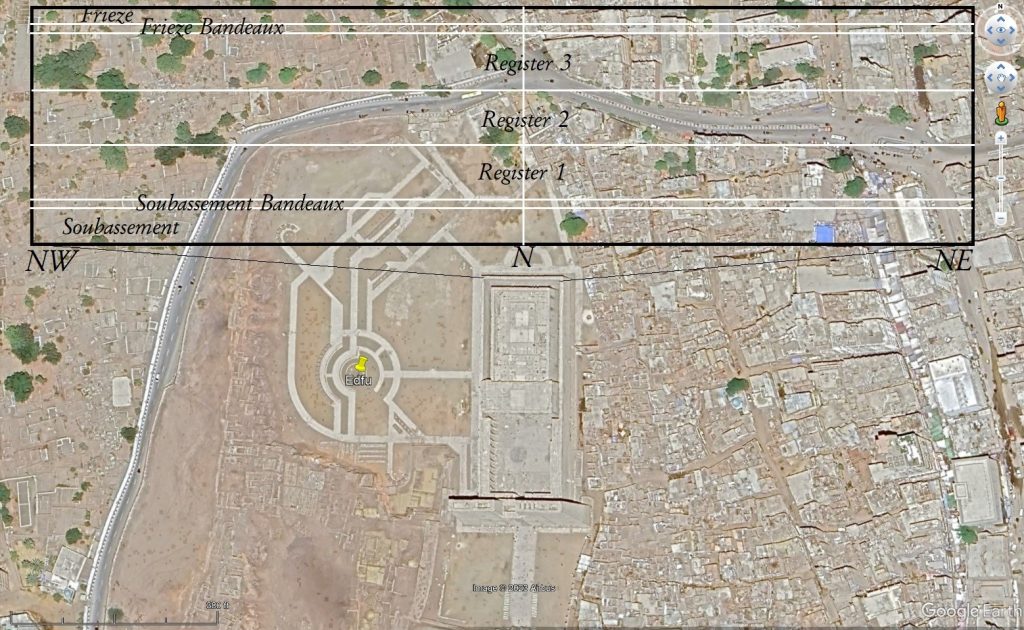

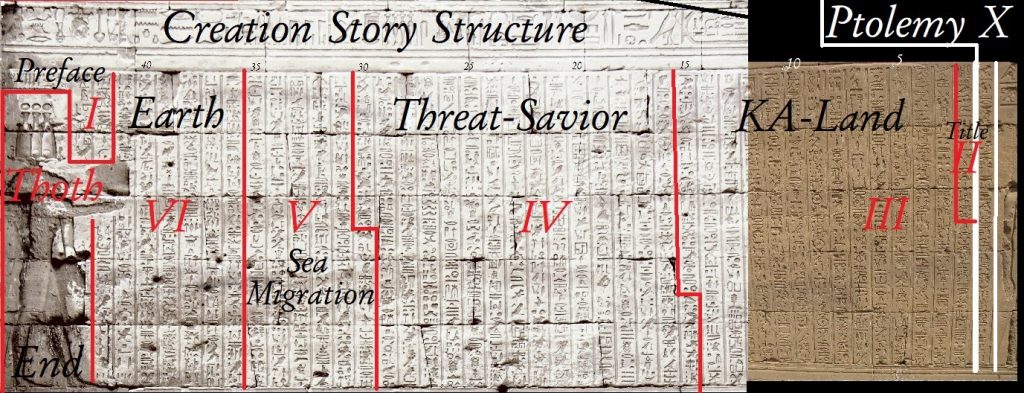

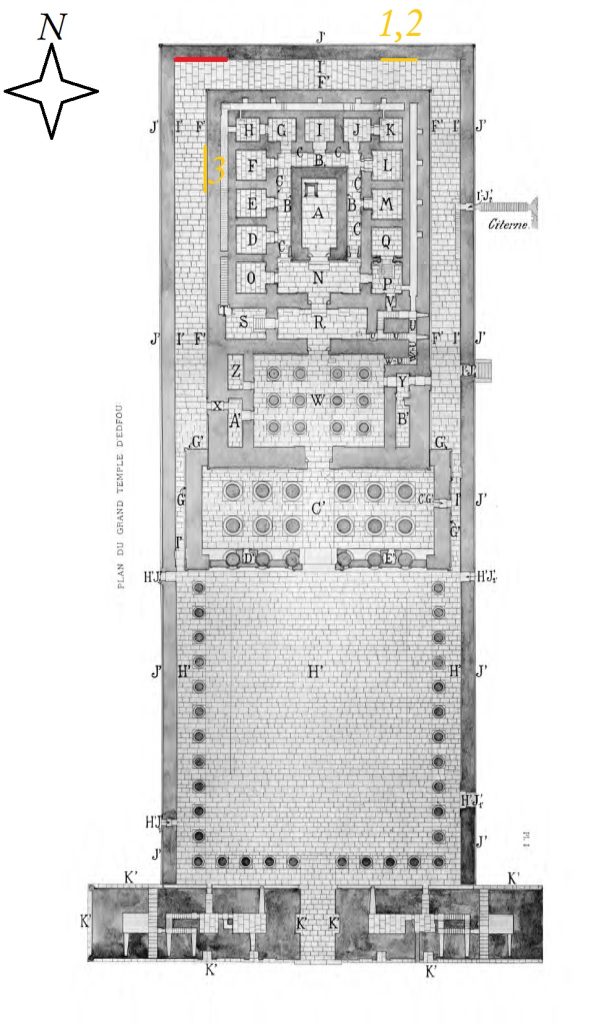

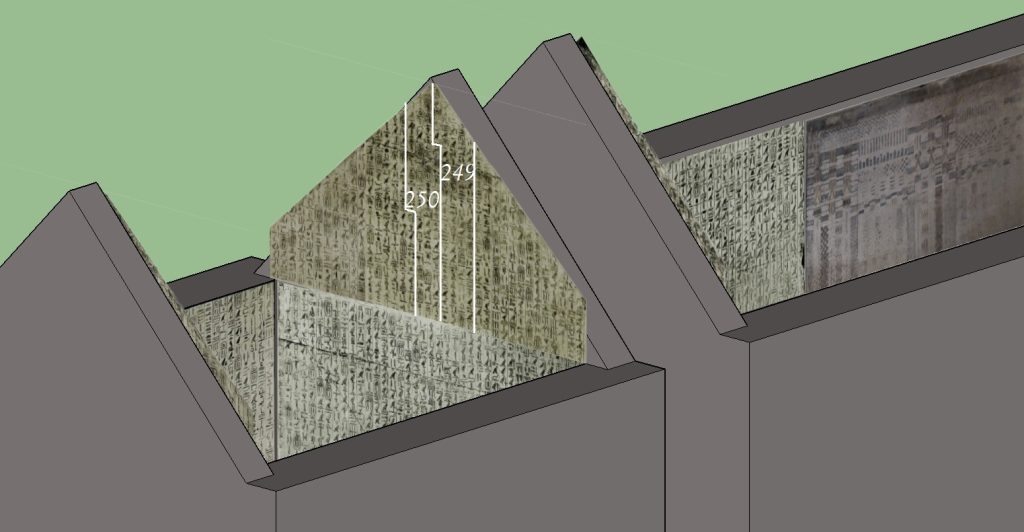

Figure 7: Schematic of the topography of the Edfu texts using the north wall of the enclosure as an example. The creation story is in the third, topmost register near the corner with the west wall. Image from Google Earth.

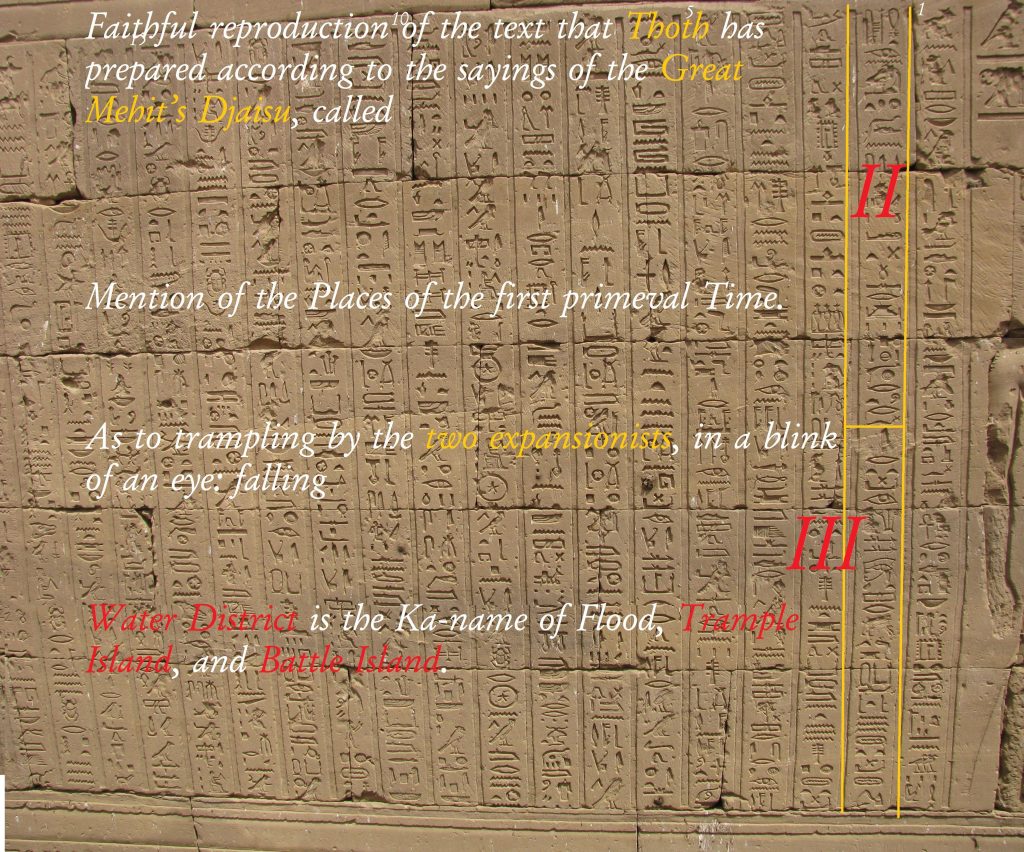

The Temple of Horus at Edfu, Egypt was built over a one-hundred-eighty-year-long period by the Ptolemies beginning in 237 BC, more than a century after Plato died. Temple scribes used cursive hieroglyphic, for example hieratic9 originals written in Middle Egyptian, edited, redacted them, and reproduced them on the walls of the temple written in a new form of hieroglyphic unique to this era across Egypt’s provinces. The problem is few today can read it.

Under the sponsorship of the Ptolemaic kings, possibly in exchange for allegiance, the scribes synthetically created a brand-new hieroglyphic script to bring to life texts written in a centuries-older form of the language only they could speak amongst themselves because their contemporaries spoke and wrote in a much later phase of Egyptian called Demotic, and, of course, in Koine Greek. When I first read Dieter Kurth’s translation of the creation story in German I knew I was looking at something extraordinary. Kurth, in a footnote of his 2014 Edfou VI, comments that this is among the most difficult texts in the entire temple, located on the inner face of the north side of the enclosure wall, in the topmost register some 30 feet above the ground where tourists can never see it. The location of the creation story can be seen when, in his 1998 documentary, Graham speaks of the survivors who settled in Egypt and built the sacred mounds.

Figure 8: The creation story marked in red is on the western half of the north wall of the enclosure. Screenshot from the film Quest for the Lost civilization.

It extends over forty-two contiguous text columns that span Chassinat’s lines 180,15 to 185,2 in Edfou VI, and which correspond to Eve Reymond’s first sixteen sections of, what she calls, the first cosmogonical record. Her seventeenth section is on the topmost register of the east side of the enclosure dealing with the construction of the primordial Edfu Temple. Her second cosmogonical record in four sections comes from the topmost register of the west side of the enclosure dealing with, what I interpret, as the details of the end of the creation story in a location called pꜤjt-Island.

The contiguity of the text columns containing the creation story is important because Reymond refers to one or the other of her first sixteen sections in different parts of her book, which may, at times, confuse the reader to think that they are topographically separate text fragments in the temple, which they are not. To make matters more complex, Kurth points out that coherent content in some cases may be fragmented. These text fragments may then be found in different parts of the temple, however, positioned according to the overall topographical plan and meaning of the temple architecture.10 The topography of these fragments is non-random, in other words. In a moment, I will show the evidence that connects a set of related passages that deal with the Island of Fire and the Lotus Offering Ritual.

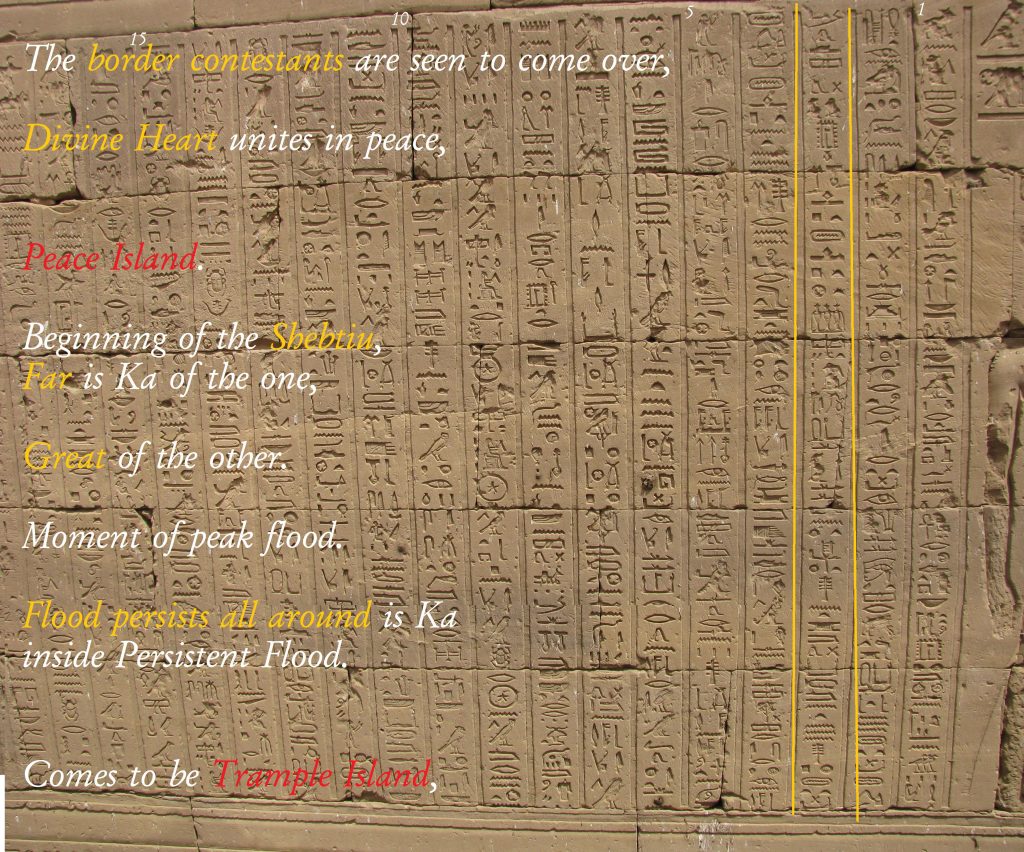

But first, here is the basic structure of the non-fragmented, contiguous creation story after King Ptolemy X Alexander’s introduction, Thoth’s preface (I), and story title (II): From the sunken remains of an island in which two combatants once fought, peace is made between them by the KA11-creator god, Divine Heart. These two, so-called Shebtiu, and seven, flood-born creation word spirits called Djaisu become his executive facilities to ḫf-conceive and njs-utter into re-existence this dormant realm of islands, towns, a sky, and a perch of woven reeds to become the throne seat of Horus who represents the Sun god on Earth. Indirect, textually only insinuated clues suggest that this is an act of resurrection as opposed to original creation (III).

Figure 9: The creation scene relief next to the text of the creation story. Image composite made with photos courtesy of the German Edfu Project and Dieter Kurth.

Figure 10: The basic structure of the creation story in six parts. Photos courtesy of Charles Lancelotta and the German Edfu Project; modified.

When this KA-realm is threatened by the primordial enemy, the Sun god’s evil twin Re-snake the light stealer, the protective Ptah-Tatenen appears and prevails over the threat to the Sun and Horus using his harpoon and spear (IV). This disturbance, however, prompts a relocation of the creative team. It migrates by sea12 to a distant location (V) where the things of Earth are made as a remake of the KA-realm, but this time with the added effort of ḏd-pillar and ḫnmw-potter spirits to fashion the KAs into material substance using jḫt-creation matter. Finally, this new realm becomes the seat where Horus settles as Horakhty and the original13—as opposed to its latest iteration, the remains of which still stand today—temple of Edfu is established (VI).

There is also a synopsis of the creation story written on the Friese band at the top of the western wall above Reymond’s second cosmogonical record demonstrating how related story fragments were topographically aligned on the walls of the temple. These duplications are important because they complement each other with respect to story details mentioned in one instance, but not the other, and vice versa.14 The quick take-away here is that both topography and common story elements form bridges between otherwise physically separated, non-contiguous text blocks.

In the case of the creation story there is one other effect I discuss in my translation paper: inexplicit, textual, and architectural thematic imbuing. An aura of resurrection hovers over the story. This aura is noticeable when one recognizes the, at times, unusual hieroglyphic orthography and word choices of the text, and the fact that it is written across the aisle below where the Osiris Chamber is in the naos. Osiris is never directly mentioned by name in the story, but his influence over the text is noticeably present. This is a fascinating effect the temple scribes employed, but I cannot expand on it in this article. Suffice it to say that it is important to consider how a given text block is written, where it is written, and what is written and illustrated in relief nearby.

The beginning of the creation story, also known as the Memphite Cosmogony, has an important link to another story whose various instances are located 1)15 on the eastern Friese band of the north wall, 2)16 the topmost register of the eastern half of the north wall near 1), and 3)17 the topmost register of the western wall of the temple naos. What ties these three locations together is the lotus theme (1-3), the Lotus Offering Ritual context (2: Ptolemy X; 3: Ptolemy VIII), the Island of the Egg/Island of Fire theme (1-3), and the theme of the primordial chaos gods called the Ogdoad18 (3). It is via the relationship between the Ogdoad and the land-raising power of nature Tatenen, mentioned in 3), that this second story ties into the Creation Story, where Tatenen appears in part IV. But there is a much older text where we find explicit evidence proving that this story is the prequel to the creation story. For that, we will visit the Pyramid of Unas in a moment. First, here are the three synopses:

Figure 11: Illustration of the temple plan. Approximate locations (marked in yellow) where the Lotus theme is mentioned on the inner face of the enclosure wall and the exterior wall of the naos. The location of the creation story is marked in red. Chamber H is the Osiris Chamber, Chamber M is for Mehit. Modified from Table I, Le temple d’Edfou 9 (first Edition 1929, second Edition 2009) by Emile Chassinat. Courtesy of the Institut francais d’archeologie orientale.

In 1) we learn the relationship between the lotus/lily19 and the egg during the first moment of light creation. The Sun child is born from a rising bud surfacing from the depths of the cosmic sea. Its petals are represented by the two, royal emblematic mothers, vulture and cobra, who cover it within the protective shell of an egg. When they release the Sun, its glowing eyes illuminate everything from the Island of Fire.20

In 2) we learn that the lotus stems from the primeval waters of Hermopolis from the Island of Fire and that this island is also called the Island of the Egg.

In 3) we learn that the primeval gods of creation created Atum21 and that the lotus is a symbol of the Island of the Egg, the seat of the flame. These gods are then further addressed as the ones whose creation preceded the creation of everything else. They are identified as the Ogdoad who are self-created without parents. They arose on the banks of a primeval mound within a primeval lake. They are the princes of eternity and the lords of infinity. They made the lands of Egypt, and their kingdom endures like the circling Sun and Moon. They created the primeval egg, fertilization and birth. They gave rise to Tatenen and Re, who both appear in the creation story. With Re, they created the first light. They are the jubilating primates who cheer the Sun.22

In summary, this second story, also known as the Hermopolitean Cosmogony, describes an Island of Fire with a primordial great lake from which an earthen mound emerges, and from where the eight original creator gods arise parthenogenetically, so to speak: The Primaeval Ones, also known as the pꜤwtjw. In that lake they have a lotus arise enshrouding an egg which releases the Sun god Re and its evening aspect Atum from the protection of the two primordial mothers of creation so that he shall illuminate eternal darkness and invisibility forever.

Based on this description, the authors Ian Driscoll and Matthew Kurtz in their interesting 2010 book Atlantis: Egyptian Genesis also recognized some elements of Plato’s Atlantis narrative.23 In one instance, however, I couldn’t tell if they may have conflated Reymond’s translation24 of ḏt as in “body,” with ḏd as in the ḏd-pillar and took this to mean that there was such a pillar on the Island of Fire25 that was recreated as the perch of Horus in the creation story.26 I have to expand here to explain this important issue.

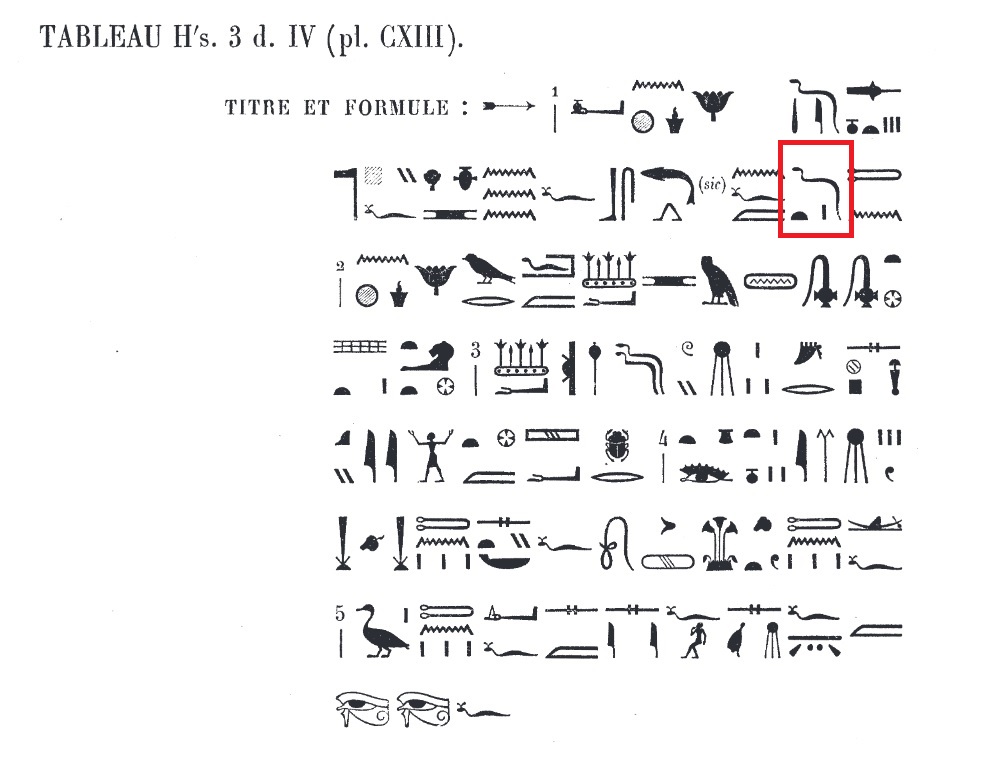

Figure 12: The spelling of ḏt as in “body.” There is no mention of the ḏd-pillar. From Le Temple d’Edfou. Tome Cinquième, page 84.

In support of this idea, they also cite Reymond’s translation of Chassinat 182,2-182,4 in her 1962 paper The Primeval Djeba.27 Her translation of this passage written into the bottom of the sixth and top of the seventh column of the creation story is at odds with the most recent translation by Kurth, in which no ḏd-pillar is mentioned. Rather, in the passage in question, the ḏd-hieroglyph is a word sign for the verb “fasten” in English, instead of “Djed-pillar.” While the ḏdw (plural of ḏd) are indeed mentioned later in the creation story as the “Enduring Ones” in another context, the ḏd-pillar does not play a part according to Kurth’s translation.

Reymond also recognized the phrase “place of the ḏd-pillar,” in Chassinat 177,3 in the third register of the inner face of the west enclosure wall.28 By contrast Kurth translates this passage into the German equivalent of English “‘Brought to you is the reed, which carries the site where endurance and strength are.’”29 In other words, Kurth reads the Djed-pillar as “endurance.” I think this is equivocal enough for me to warrant posting the image of the original text. Note the determinative of the boat after the Djed, translated as “there,” in Ptolemaic hieroglyphic.

Figure 13: Equivocal text on the western wall of the enclosure in the third register. Highlighted in red is the phrase bw ḏd. Image courtesy of the German Edfu Project and Dieter Kurth; modified.

Even if Reymond’s reading were to be more accurate than Kurth’s in this case, the events described in the text are not on the Island of Fire. Rather, they seem to be those details of the settling on Earth not mentioned in the creation story of the Memphite Cosmogony, written nearby on the north wall where it meets the west wall.30

Further south on the west wall, near the start of the texts that occupy the topmost register is an explicit mention of the ḏd-pillar, here marked with a context sign in the shape of the seated Osiris. The absence of this context marker in the prior record may explain the different translations.

The context of this passage, likewise, clarifies the meaning of the ḏd-pillar sign:

Words to be spoken by Osiris, the column, the great god, who dwells in Behedet, Anhur pronounced just, Geb’s heir, the Djed-Pillar in Busiris, Andjety in Andjety, foremost of the westerners, Lord of Abydos.

Figure 14: Explicit mention of the Djed-Pillar on the west wall of the enclosure. Highlighted in white is the phrase ḏd m ḏdw for English “Djed-Pillar in Busiris.” Image courtesy of the German Edfu Project and Dieter Kurth.

In reliance on Reymond’s translation and interpretation of these passages and her commentary in her 1969 book The Mythical Origin of the Egyptian Temple, Driscoll and Kurtz drew a parallel between the ostensible mentions of the primeval ḏd-pillar at Edfu and Plato’s Pillar of Orichalcum in his narration of the temple of Poseidon on Atlantis.

Without choosing here one translation over the other, I merely wish to use this example as an admonition to be cautious when citing Egyptian texts without the benefit of seeing the original writing, but also to show that even when mistakes are made in this difficult business of reading them, these mistakes may help others to discover new things. Mistakes can be a blessing in hindsight. Those who make them ought to be thanked, not scolded. In this case, whether Djed-pillar or not, the essential theme is that of written laws of divine origin. Here are two examples in Egyptian texts that parallel what Plato wrote in Critias.

In Critias 119c Plato presents divine law as the “precepts of Poseidon,” carved into a gilded pillar in the center of the Temple of Poseidon on Atlantis. They govern how Poseidon’s royal heirs conduct affairs between themselves as the bull sacrifice and blood ritual vividly demonstrates. This is a not-so-subtle reminder of an episode in real Athenian history, when written laws began to be displayed in public, first the harshly punitive Draconian version, mocked as having been written with blood,31 then repealed and replaced by their more liberal version of Solon.

First, at Edfu, reference is made to a written wḏt-decree from which all creation is uttered in a phrase that immediately precedes the text I cite in 1) above. Referring to Horus it states, translating Dieter Kurth’s German into English:

“His decree that his father [Re] has given him is in his hand when he lets human beings come to be, bears the gods, and creates all that as something that his heart has created, when…”

Figure 15: The written creation decree of Horus called wḏt. Excerpt from the Friese band on the eastern half of the north wall. Photo courtesy of Émile Chassinat and the German Edfu Project; modified.

The Friese band inscription dates this act of creation by the creator using a written creation decree to the time of the lotus rising on the Island of Fire. Continuing the translation:

His decree that his father has given him is in his hand when he lets humans come to be, bears the gods, and creates all that as something that his heart has created, when the stem with the lotus bud blossoms from the seed of Nun…

The difference from Plato’s Pillar of Poseidon is that the Egyptian creation decree is written on papyrus, woven therefore from reeds as is the original perch and seat of Horus in the creation story. The other difference is that while the precepts of Poseidon dictate divine law concerning conduct on Earth, the wḏt-decree dictates how creation shall proceed.

Second, a written document of divine provenance is also mentioned in a key passage of the Pyramid Texts that presents us with evidence to connect the creation story at Edfu with the story of the primeval gods on the Island of Fire. In fact, this passage identifies the Memphite Cosmogony as the sequel to the prequel that is the Hermopolitean Cosmogony corroborating Eve Reymond’s suspicion that the Island of the Fire/Egg and the Island of Trampling are equal in their function in creation.32 They also corroborate Graham Hancock’s distillation of the fundamental story’s structure based on Reymond’s translation and interpretation.33

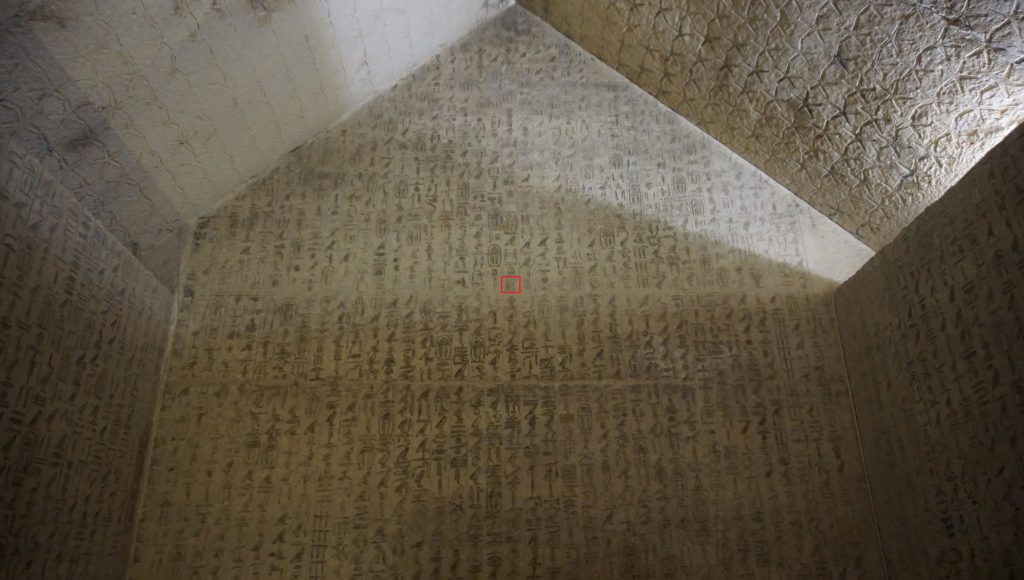

Figure 16: The west gable of the antechamber in the Pyramid of Unas. Highlighted in red is the position of the words “Scroll of God” under the peak of the gable.

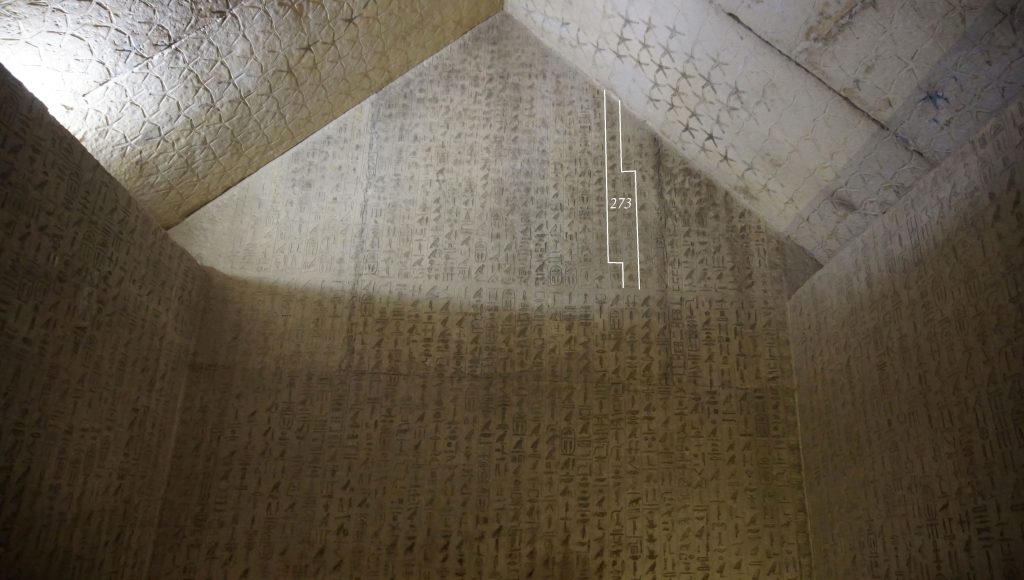

To find this passage, one must look up to the right gable of the antechamber when one first enters the Pyramid of Unas at Saqqara, Egypt. Carved into the walls of this pyramid’s inner chambers and corridors are the oldest known religious texts in the world in their earliest known version in Egypt. The most recent, and up-to-date English translation (Allen 2005) is that of James P. Allen, one of the world’s foremost experts on Old and Middle Egyptian.

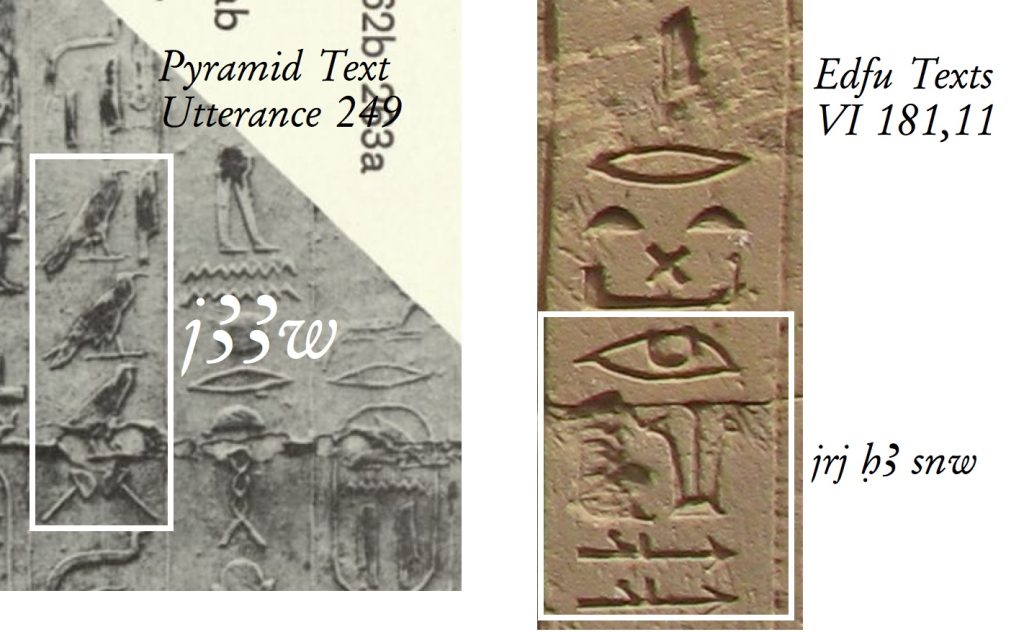

The Scroll of God is mentioned in an utterance immediately following an utterance about the Island of Fire, which is mentioned twice total in the Pyramid Texts of Unas, once on each gable. The earlier instance is in the west gable. It contains the sequential utterances 249 and 250, entitled by Allen as “Appearing as Nefertem,” and “Appearing as Perception in the Sunboat.”34 Here are the synopses of these two utterances:

Figure 17: Utterances 249 and 250. Graphic model of the interior of the Pyramid of Unas courtesy of Ali Reza Samsami.

Utterance 249: Unas creates order from chaos on the Isle of Flame where two combatants are fighting. He emerges as the lotus Nefertem on the morning horizon, after a night of a great flood sent by a goddess during which his royal head cobras protect his linen.

Utterance 250: Unas joins hearts to make peace. He is in possession of the Scroll of God that gives him perception. He is now in charge of KAs. He speaks of great things during the festival of red linen.35 He is reserved of heart in front of Nu’s cavern.

To complete the information learned from Utterance 249 about the Isle of Flame, the second instance of its mention in the (in)famous Cannibal Hymn Utterance 273 on the east gable across the chamber reads:

Unis is the sky’s bull, with terrorizing in his heart, who lives on the evolution of every god, who eats their bowels when they have come from the Isle of Flame with their belly filled with magic.

Figure 18: The two combatants in the Pyramid Texts and the two expansionists at Edfu. Images courtesy of Piankoff, the German Edfu Project, and Dieter Kurth; modified

Figure 19: The east gable texts containing Utterances 273-275. The part of Utterance 273 that mentions the Island of Fire is marked in white. Pyramid of Unas in Saqqara, Egypt.

The word “magic,” is English for the Egyptian word HEKA, the skill to use phonetic mimicry to invocate KAs, basically to ethereally create living beings and gods.36 The logical sequence from these three utterances is therefore that there is war between two opponents on the Island of Fire. Unas makes peace between them. After a flood, he emerges on the horizon in possession of divine perception and HEKA, the power to conceive and create KAs.

This thematic sequence builds the needed bridge to understand how the Memphite Cosmogony connects with the events of its prequel in the Hermopolitean Cosmogony as told at Edfu. This bridge eluded Eve Reymond because, as she noted,37 it is not explained, only hinted, at Edfu. The sole hint available to Reymond was a single, though consequential, word.

The creation story begins with the mention of two “trampling” combatant expansionists on an island in a flooded district called wꜤrt. This is Trampling Island, also known as Island of Battle. The word wꜤrt for English “Water District” is associated with the flood that issues from the aqueous grave of Osiris,38 as it is written on the walls of Hadrian’s Portal at the Temple of Philae, first translated in 1913 by the German Egyptologist Hermann Junker in Das Götterdekret über das Abaton. The best way to appreciate the connotation is Figure 9 in Junker’s work, where you see a water fountain from the knee of the mummy of Osiris.39 Literally, wꜤrt means leg, but in the creation story it assumes the more figurative sense of quarter/district, specifically “water district” because of the Water Channel Sign that immediately follows it in Column 2. Eve Reymond recognized the dark connotation associated with this word choice as the watery graveyard of none other than Osiris. This is only one of several Osirian insinuations in the creation story I discuss in my published English translation. The idea is that a drowned realm lies dormant waiting to be brought back to life.

Thus, the creation story begins with a dormant, watery realm, once the site of battle and a flood. This watery realm was the Island of Fire, now sunken and called the Island of Trampling and Battle, as suspected by Reymond. The survivors are the two combatants, the seven flood-born Djaisu-recorded creation words, and the creator called the nṯrj-Divine Heart,40 who makes peace between the two combatants. These two then become the Shebtiu, Far and Great,41 the Divine Heart’s mental facilities of imaginative creation and focus uttered into existence by the KA-god. He, through them, begins to recreate the drowned realm by calling out KA-names to make its parts come back to life. The creation story is littered with KA-names of entities and their coming to be, including Horus and Re, the chief gods of the Sun and sky.

Figure 20: English translation of the opening sequence of the creation story. Modified image courtesy of the German Edfu Project and Dieter Kurth. The second column of the text is highlighted. The Roman numerals indicate structural parts of the story, and the English translation is based on Dieter Kurth’s German.

The creative power employed by Divine Heart is analogous to the perception and authoritative utterance acquired by Unas in the Pyramid Texts, after he brings order to the flooded Isle of Flame thrown into chaos by the two combatants.

Figure 21: Divine Heart makes peace between the combatants who become the Shebtiu. Modified image courtesy of the German Edfu Project and Dieter Kurth.

4. Discussion

In summary, the Pyramid Texts speak of the power to control KAs as having been acquired after forging peace on the Island of Fire. Similarly, at Edfu Divine Heart incorporates the two, formerly quarreling Shebtiu as his creative facilities once he forges peace between them. They, and the seven recorded and archived Djaisu-creation words who emerged from the great flood are the surviving spirits of the Island of Fire who recreate their drowned world by calling out KAs. When this KA-realm is threatened, they migrate to the Earthly realm and copy the KA-realm to create its material version on Earth together with the ḏdw-stability and ḫnmw-potter spirits. This material copy becomes the seat of the primordial Edfu Temple, the throne seat of the creator god’s representative on Earth, Horus.

Taken metaphorically, these two cosmogonies could be thought of as projections of the creator’s mind. Only when opposing inner and irrational currents can be united in peace for reason to be restored can the perceptive and executive powers of the divine mind be creative and resurrect creative thoughts from their subconscious, “flooded” remnants. When this psychological model of the cosmogonies is applied to Plato’s dialogs, their structure and presentation make more sense. Someone may have well thought of this idea before me. I am only illustrating with it the parallel structures without claiming to have thought of it first. For example, this model helps explain why Plato wedges his cosmogony delivered by Timaeus in Timaeus between the two monologs of Critias: the initial synopsis of the Atlantis story in response to Socrates’ request for his republic in motion, and Critias’ later monolog about the histories of Athens and Atlantis in Critias.

In Timaeus, Plato has Critias introduce the synopsis of the Atlantis story, an epic battle between two powerful combatants that ends with the destruction of both. What follows is Timaeus’ presentation of the cosmogony of a mental creator god who uses his intellectual facilities to reason out the characteristics of an original, timeless, and perpetually existing cosmos to fashion from it a sole and unique cosmic copy with soul, time, and gods, who, in turn, create humans.

One way to explain this intercalation of Timaeus’ monolog is Plato’s overarching point: An imperfect republic whose society and military are materially corrupted cannot prevail against an uncorrupted, noble foe. To explain how the soul can be corrupted, Plato has Timaeus first explain the fabric of the cosmos, itself soulful, but apt to be hampered by chaotic orbital motion of an imperfectly copied eternity now called time. This cosmic soul imbues everything within the cosmos including gods and humans. But since it is an imperfect copy of the perpetual eternity of the original the creator used as a template to fashion the cosmic copy, it is subject just the same to irrationality and corruption due to the, at times, chaotic orbital motions of the soul that likewise can afflict humans. In Timaeus 87a-b, Plato explains how the unvented vapors of bad humors inside the human body affects the “movement of the soul,” and thereby cause “bad temper and bad spirits.”

Soulful and reasoned creation can only happen when these commotions are quelled. The Atlanteans, despite their divine origin from Poseidon, succumb to the corruption of the soul. The reason, human temper, has now already been explained when Critias says in Critias 121a-b:

But when the portion of divinity within them was now becoming faint and weak through being ofttimes blended with a large measure of mortality, whereas the human temper was becoming dominant, then at length they lost their comeliness, through being unable to bear the burden of their possessions, and became ugly to look upon, in the eyes of him who has the gift of sight; for they had lost the fairest of their goods from the most precious of their parts;

The Socratic prescription against this corruption is the perfect society that physically shields the guardian class from the tempestuousness of the people at large and practices societal planning. This is one way to understand the two known dialogs of Plato as a comprehensive whole. Moral conduct requires reason. For reason to prevail, tempers must be calmed so that noble conduct is kept pristine from corruption. Atlantis starts off as pristine, until tempers get the better of it.

This is the same fundamental idea as that which transpires from Egyptian insights expressed since long before Plato in the Pyramid Texts and expanded upon in the Edfu Texts. My own take-away is that Plato did what he had his creator do in Timaeus. He used a fundamentally Egyptian Vorlage42 and made a not quite identical copy of it. He may have detailed it with descriptions of his own making, but structurally and metaphorically, and thus substantially, adopted the basic logic of the two cosmogonies as they are recorded in the Edfu Temple. The final composition of the dialogs could, in my opinion, be called an adaptation of originally adopted Egyptian themes for his Greek audiences. His claim that he learned these themes from Solon is therefore quite believable, making the Noble Lie Thesis rather unbelievable.

Having studied the Edfu cosmogonical texts in depth, personally, I find it difficult to imagine how this could be pure coincidence, or Plato’s invention. To accept the Noble Lie Thesis in its extreme version, I would have to ignore the evidence I have presented here in its entirety and accept that Plato lied about the Egyptian origin of the Atlantis story. Many critics have focused on the implausibility of what is written in Critias in constructing this thesis, but the evidence that Plato didn’t lie, as far as I see it, comes chiefly from Timaeus, a discrete departure from how Greek thinkers before Plato viewed the creation of the cosmos, for example Hesiod’s anthropomorphic Theogony. I have highlighted some of this evidence in the introduction, for example the fundamental cosmogonical concepts such as LOGOS concept basically identical with HEKA, Plato’s dual eternities called ḏt and nḥḥ in Egypt, Plato’s original and copy cosmos analogous to the original KA and copied Earth realms at Edfu, and the emphasis by Plato on the concept of becoming as opposed to perpetually being, analogous to ḫpr in hieroglyphic.

Another important theme in cosmogony is the soul. Compare the fashioning of the soul between Plato and Edfu. In Timaeus 34e, we read

And the Soul, being woven throughout the Heaven every way from the center to the extremity, and enveloping it in a circle from without, and herself revolving within herself, began a divine beginning of unceasing and intelligent life lasting throughout all time.

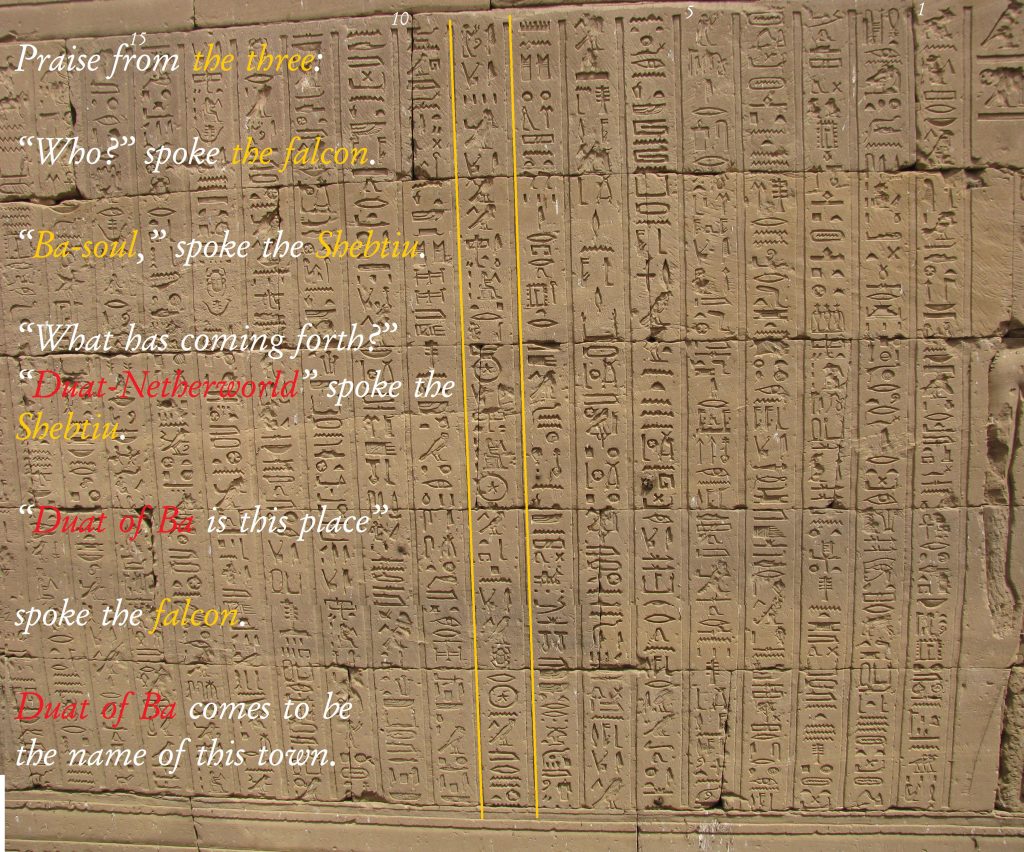

In the ninth column of the creation story at Edfu, Horus asks the Shebtiu:

“Who,” spoke the falcon. “BA-soul,” spoke the Shebtiu. “What has coming forth?”

“Duat-Netherworld,” spoke the Shebtiu. “Duat of BA is this place.” Spoke the falcon. Duat of BA comes to be as the name of this town.

I use this example to showcase the spectrum that ranges between adoption and adaptation of any given theme. Clearly, these two renditions are not identical. What they substantially share, however, is the living soul theme woven into the sky and encircling it in Timaeus, vis-à-vis the sky Netherworld-soul represented by a star within a circle and a bird in the Edfu creation story. A unique detail in Plato’s adaptation of this theme is that the soul revolves within herself.

Figure 23: Column 9 of the creation story where the Duat of BA-soul is mentioned. The sign of the Duat-Netherworld is a star within a circle. Modified image courtesy of the German Edfu Project and Dieter Kurth. English translation is based on Dieter Kurth’s German.

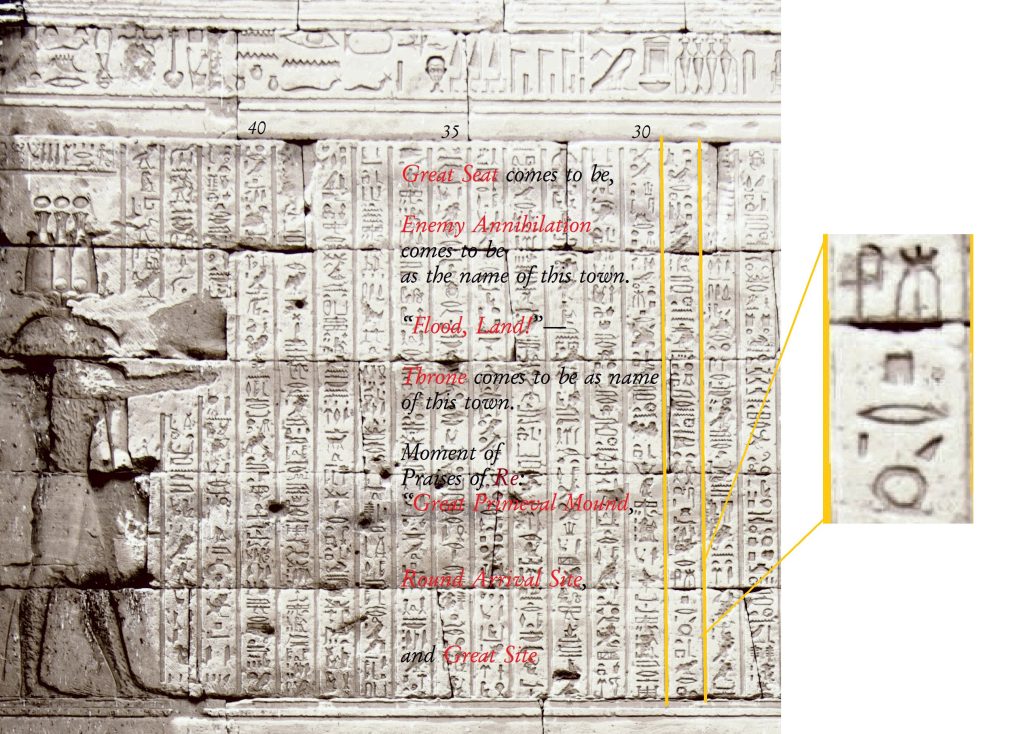

While many of the details of Atlantis told by Critias in the second dialog do not appear as such in the creation stories at Edfu—which is why the Djed-pillar was an important topic to deal with earlier—there are a few significant exceptions. The first is mentioned in the 29th and 30th column of the creation story where reference is made to a msprt šnjt “round arrival site,” at the great primeval mound “laden with plants as far as the Sun shines.” The word “round” in the name “Round Arrival Site” is spelled with the ring hieroglyph. This passage is reminiscent of the description of Atlantis in Critias 113c-d:

…and Poseidon, being smitten with desire for her, wedded her; and to make the hill whereon she dwelt impregnable he broke it off all round about; and he made circular belts of sea and land enclosing one another alternately, some greater, some smaller, two being of land and three of sea, which he carved as it were out of the midst of the island;

Here again, there are adopted themes that were adapted. Plato describes a low-sided mountain amid a lush plain, around which Poseidon carves circular belts of land and water. At Edfu, a great site is described as laden with plants, a primeval mound, and a ring-shaped arrival site. Plato’s unique adaptation revolves around sea god Poseidon’s marriage to the human woman Cleito.

The second exception has to do with Plato’s name for “Atlantis,” Ἀτλαντίδος νήσου, Atlantic Island. When I began to suspect that the Noble Lie Thesis might not be valid, I asked myself how Plato came up with that name. There are two commonly known theories. The first theory is that the Atlas in Critias was an intentional conflation with the titan Atlas who is deceived by Hercules to think that he will be relieved of his burden to carry the sky in exchange for stealing golden apples from the Garden of the Altantides, Atlas’ daughters the maidens of the far west. The second theory is that Atlas comes from the Berber word for mountain, “adrar.”

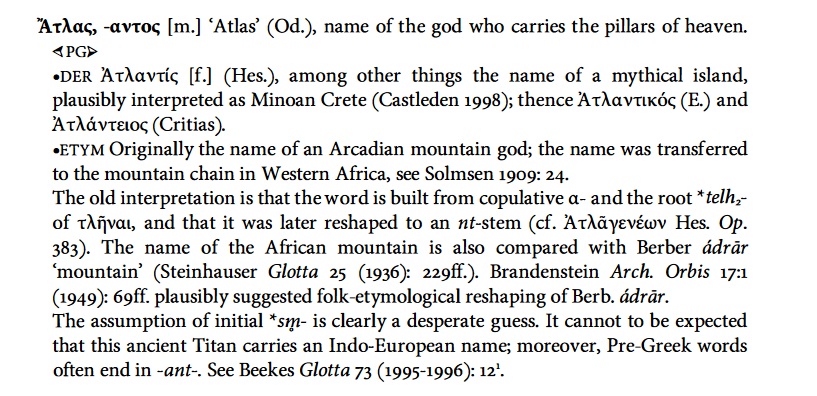

In truth, the origin of Plato’s choice of the name of this island and the ocean that surrounds it isn’t known. Consulting Robert Beekes’ 2010 Etymological Dictionary of Greek43 the following entry appears under “Atlas”:

Figure 25: Entry for “Atlas” on Page 163 of Robert Beekes’ 2010 Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Volume One.

In the older interpretation, apparently dismissed by Beekes, the word was composed of a prefix—either ha- or a- denoting “unity” (e.g., a-delphos = same womb = brother)—and the word stem -tlant, possibly a pre-Greek version of -tlas from tlínaí (τλήναί).44

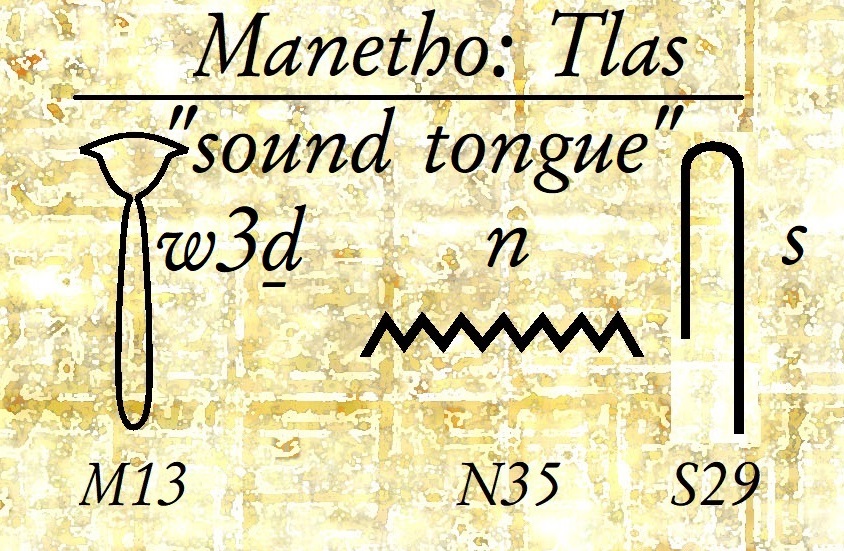

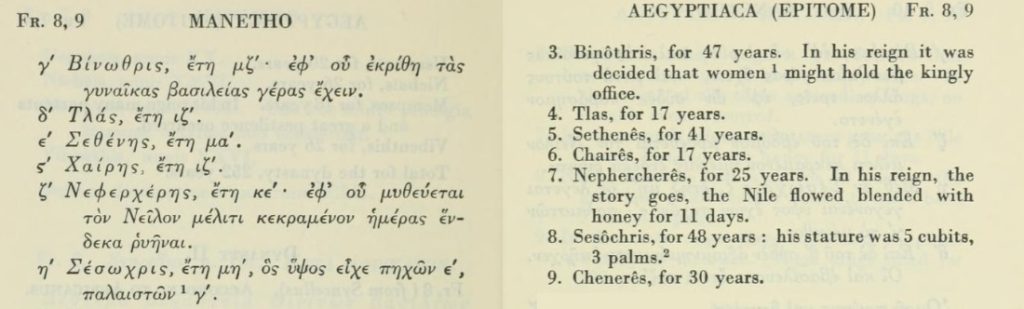

This is when it hit me like a toppling Djed-pillar. Was Beekes not aware of Manetho’s king list? Manetho is the rare, historically known Egyptian who did what Plato’s Critias says in Critias 113a-b Solon did:

…recover the original sense of each name and, rendering it into our tongue, write it down so.

Manetho was alive when the Edfu Temple’s construction began. He translated for his Ptolemaic masters into Koine Greek the hieroglyphic names of the kings of Egypt. The Greek name “Tlas” appears in the fourth entry for the Second Dynasty: the Egyptian name w3ḏns whose cartouche is listed, for example, in the Abydos King List in the Temple of Seti. What can clearly be gleaned from this Greek interpretation of hieroglyphic writing is that the Greek diagraph “tl” was meant to replace the Egyptian consonant “ḏ” pronounced like “J” in “Jim,” and the “n” was suppressed.

Figure 26: Hieroglyphic spelling of Second Dynasty king Wadjenes above, Gardiner sign numbers below, and the Greek rendition by Manetho, translated into English by William Waddell’s Manetho, pages 36-37.

Figure 26: Hieroglyphic spelling of Second Dynasty king Wadjenes above, Gardiner sign numbers below, and the Greek rendition by Manetho, translated into English by William Waddell’s Manetho, pages 36-37.

At this point it ought to be obvious to all that any attempt to search for the name “Atlantis,” or any of its derivatives in Egyptian texts is a futile effort. Either the name was never written in hieroglyphic, or it is lost, or it has been overlooked, and understandably so. You can only see what you expect to see. One of my professors in medical school once demonstrated this to us students staring at an X-ray. We missed even the most glaring pathologies because we had no clue what we were looking for.

How could I then fault the Egyptologists or classicists for failing to see what I am going to show you now? Given the above, we expect to find the name Atlantis within the creation story, if it is at Edfu. We expect the name to contain a “ḏ,” and begin with a weak consonant like “h,” “a,” or “w.” We also expect the name to appear within a fitting context such as the description of a site or place in the KA-realm. This is because Egyptian names often amounted to epithets.

Figure 27: The hieroglyphic phrase that reads in English “Flood-born, Pristine Sites,” highlighted in red on the Friese band of the west wall of the enclosure. Modified image courtesy of Émile Chassinat and the German Edfu Project. The English text below is from Plato’s Critias113a-b.

And this takes me, together with you, to that moment I recount at the beginning of this article when it stared at me. “It” is a phrase written into the Friese band on the western wall of the enclosure, part of a narrative that recounts the synopsis of the creation story. The phrase is shown in the black-and-white photo at the top of this article: msjt nt wḏ3 swt, “born of the flood, pristine sites,” or “pristine sites born of the flood.” This comes from a passage that reads in English from Dieter Kurth’s German:

Re praises the great primeval mound: “The High Hill on which the KA of the god is mighty, born of the flood with45 pristine sites,” and so comes to be Mesen, and the Place-with-pristine-Sites comes to be. “Behedet is there until all eternity, which is the capital of the sites where the primeval gods dwell,”…

Applying Manetho’s diagraph substitution and Beekes’ old etymological interpretation, I propose the following:

-

Transliteration: wḏ3 swt msj nt

-

Diagraphic conversion of “ḏ”: w-tl-a swt msj nt

-

Contraction and Pre-Greek “ant” substitution: wtlant msj nt

-

Weak consonant replacement with Greek copulative a-: Atlant msj nt

Translation: Pristine Sites born of the Flood

Is this the smoking gun? Is this how Solon rendered “Flood-born Pristine Sites”? Was this the name of a place older than Egypt’s own history as told to him by the Egyptian priest, whose story was written on the walls of the Temple of Neith at Sais, translated by Solon into his native Greek, and brought back by him to Athens, where one day, some two centuries later, Plato would use it as a canvas onto which to paint Timaeus and Critias?

This, I must leave to you to decide for how could I ever be so sure to not tell you a common lie?

5. References

Allen, J. P. (2014). Middle Egyptian. An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. Third Edition. Cambridge University Press.

Allen, J. P. (2005). The ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts. Peter der Manuelian (Ed.) Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature.

Beekes, R. (2010). Etymological Dictionary of Greek. In Alexander Lubotsky (ed.) Leiden Indo-European Etymological Dictionary Series. Leiden, Boston: Brill

Chassinat, É. (1931). Le Temple d’Edfou. Tome Sixième. Le Caire: Imprimerie de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale. URL: https://www.ifao.egnet.net/uploads/publications/enligne/MMAF023.pdf

Driscoll, I., Kurtz, M. (2010). Atlantis: Egyptian Genesis. Self-published: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

German Edfu Project (2002-2017). Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen. Archived URL: https://web.archive.org/web/20220613075059/https://adw-goe.de/forschung/abgeschlossene-forschungsprojekte/akademienprogramm/edfu-projekt/

Griffiths, John G. (1985). Atlantis and Egypt. Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, Bd. 34, H. 1, pp. 3-28.

Hancock, G. B. (2015). Magicians of the Gods. London: Hodder & Stoughton Ltd.

Hancock, G. B. (November 5, 1998). Quest for the Lost civilization. Documentary, TV Miniseries, Episode 3, directed by Timothy Copestake.

URL: https://youtu.be/T5DNvYMtkyk?t=8746

Hancock, G. And Bauval, R. (1996). The Message of the Sphinx. New York: Three Rivers Press.

Johanson, T. K. (1998). Truth, Lies and History in Plato’s Timaeus-Critias. Histos, 2, pp. 192-215.

Kurth, D. (2024). Philosophisches Denken in den Texten des Tempels von Edfu. Göttinger Miszellen, in print.

Kurth, D. (2021). Die Inschriften des Tempels von Edfu. Abteilung I Übersetzungen; Band 5.1 Edfou IV. Hützel: Backe-Verlag.

Kurth, D., Behrmann, A., Block, A., Brech, R., Budde, D., Effland, A., von Falck, M., Felber, H., Graeff, J.-P., Koepke, S., Martinssen-von Falck, S., Pardey, E., Rüter, St., Waitkus, W., Woodhouse, S. (2014). Die Inschriften des Tempels von Edfu. Abteilung I Übersetzungen; Band 3. Edfou VI. Gladbeck: PeWe-Verlag.

Kurth, D. (2009). Einführung ins Ptolemäische. Teil 1. Hützel: Backe-Verlag.

Neyland, R. and Seyfzadeh, M. (2022). The Bearded Lady of Giza: Appropriation, Conspiracy, and Veiled Protest in the Pyramid Texts of Unas. Archaeological Discovery, 10, pp.: 136-192.

Piankoff, A. (1968). The Pyramid of Unas. In Egyptian Religious Texts and Representations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Reymond E. A. E. (1969). The Mythical Origin of the Egyptian Temple. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Reymond E. A. E. (1962). The primeval Djeba. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 48, pp. 81-88.

Seyfzadeh, M. (2024). English Translation of an Egyptian Creation Story Recorded at the Temple of Horus in Edfu, Egypt. Archaeological Discovery, 12, pp.: 93-114.

Smith, M. (2019). Between Temple and Tomb: The Demotic Ritual Texts of Bodl. MS. Egypt. A. 3(P). Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

Video review, URL: https://youtu.be/dg727sMSCKU?si=xHi7HaO48d-QC2ot

Waddell, W. G. (1940). Manetho, with an English translation. London: W. Heinemann

6. Dedication

For you, Robert Bauval, with much love and many thank-yous.

7. Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Graham Hancock for line-editing and proof-reading the manuscript for this article.

8. Notes

1.1 The image shows the inner face of the west side of the enclosure wall of the Temple of Horus at Edfu, Egypt, featuring the uppermost register and Friese band. Modified image courtesy of Émile Chassinat.

2.2 Edfu is also known as Apollinopolis Magna.

3.3 The full phrase from which this term derives by its translators in Plato’s Republic, 414c is μηχανὴ γένοιτο τῶν ψευδῶν τῶν ἐν δέοντι γιγνομένων, ὧν δὴ νῦν ἐλέγομεν, γενναῖόν.

4.4 Middle Egyptian (ME) was spoken for five hundred years from circa 2100-1600 BC. It was phased out and replaced by Late Egyptian after 1400 BC. These periods approximately (+/- 200 years) overlap the Middle and New Kingdom, respectively. (Allen 2014, page 1). Traditional Egyptian (TE) was used throughout the Late Period to rekindle the gravitas of Early Phase Egyptian (Old and Middle Egyptian). The difference between TE and ME are the occasional slip-ups of the former into Late Egyptian (Dieter Kurth, personal communication). Good reviews on Traditional Egyptian and Late Egyptian can be found here:

URL: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3fr419rk

URL: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0bg342rh

5.5 Episode: Plato’s Atlantis hosted by Melvin Bragg. URL: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m001c6t3

6.6 Seyfzadeh 2024.

Video version, URL: https://youtu.be/YDa9i-Y0vak?si=DN8VtXplyce4a-eo

Edfu Temple Introduction with Dr. Dieter Kurth, narrated by M. Seyfzadeh.

URL: https://youtu.be/EYkeCFlttgk?si=hIiY4iz28Px_5znJ

Video version: https://youtu.be/YDa9i-Y0vak?si=DN8VtXplyce4a-eo

Edfu Temple Introduction with Dr. Dieter Kurth, narrated by M. Seyfzadeh: https://youtu.be/EYkeCFlttgk?si=hIiY4iz28Px_5znJ

7.7 Timaeus 29a: [the cosmos] “has been constructed after the pattern of that which is apprehensible by reason and thought and is self-identical.”

8.8 University of Heidelberg Egyptologist Jan Assman explains the difference between the two Egyptian concepts of eternity as follows: “We can also illustrate the Egyptian disjunction of time with the help of the concepts “come” and “remain.” It is often said of neheh-time that it “comes”: it is time as an incessantly pulsating stream of days, months, seasons, and years. Djet-time, however, “remains,” “lasts,” and “endures.” It is the time in which we distinguish the completed, that which has been effected in the stream of neheh-time, which has matured into completion and has changed into a different form of time that will undergo no further change or motion.” (From page 75 in Jan Assman (2001). The Search for God in Ancient Egypt. (David Lorton, Trans.) Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press. (Original work published 1984).

9.9 Hieratic is hand-written, cursive hieroglyphic. It refers to the script in which Old, Middle, and Late Egyptian were written on papyrus until it developed into the more cursive Demotic beginning in the Late Period.

10.10 Kurth 2009, page 8.

11.11 KA corresponds to that part of a god or human that consumes sustenance to fuel its force of life. The BA is the soul that carries character and personality.

12.12 Two examples of how the hieroglyphic text clarifies that the journey is by sea are the unusual orthography of how the words “crew,” and “there,” referring to the destination, are spelled. In the former case, a mooring post is used, and in the latter case a ship.

13.13 The archaeological evidence for an older temple dated to the New Kingdom immediately east of the current temple, and an Old Kingdom settlement to the west is summarized for example in the 2014 Season of Tell Edfu by Nadine Moeller and Gregory Marouard. URL: https://isac.uchicago.edu/sites/default/files/uploads/shared/docs/ar/11-20/14-15/ar2015-Edfu.pdf

14.14 Cf. Kurth 2009, page 8.

15.15 Kurth 2014, Edfou VI, pp. 27-28. Chassinat 16,5-16,9.

16.16 Kurth 2014, Edfou VI, pp. 614-615. Chassinat 338,13-339,9.

17.17 Kurth 2021, Edfou IV, pp. 259-262. Chassinat 139,16-141,10.

18.18The Ogdoad (literally “The Eight”) are four pairs of male and female pre-creation chaos forces represented by frogs and snakes. They personified the nw and njwt cosmic sea and night sky, kkw and kkwt darkness, ḥḥw and ḥḥwt infinity, and n3y and n3yt invisibility. They were worshiped in the 15th nome of Upper Egypt at ḫmnw, Hermopolis Magna, the City of Thoth. One of Thoth’s epithets is nb ḫmnw, “Lord of the Eight.”

19.19 The Egyptian lily is often called a lotus.

20.20 Also variously referred to as the Island of (the two) Flame(s).

21.21 Atum is the creator god in the Heliopolitean Cosmogony of ancient Egypt.

22.22 This is an allusion to Thoth, one of whose manifestations is the baboon, representing Full Moon.

23.23 For example, the Pillar of Orichalcum containing the Precepts of Poseidon in Critias 119c, and the idea of royal twins who originally governed Atlantis.

24.24 Reymond 1969, page 68. Her footnote refers to Edfou V, Chassinat 84,12-84,16.

25.25 Cf. Reymond 1969 on page 88.

26.26 See chapter VI in Driscoll and Kurtz (2010).

27.27 On page 84, Reymond translates “The relic of This One, the Overlord of the ḏd-pillar is the reed that uplifted the god. The djeba of the reed is the name of Djeba in Wetjeset- Ḥor. Thus, Djeba came into existence and Wetjeset- Ḥor became the name of this domain.”

28.28 Reymond 1962, page 85.

29.29 Kurth et al. (2014), page 311.

30.30 The synopsis of the texts in the uppermost register on the west wall is that after Re-snake Apophis is defeated, a ritual is prepared that includes a recipe for Jubilee Oil. The chord-stretching ceremony is followed by laying the foundation of the primordial Edfu temple. These events expand on details not mentioned in Part VI of the creation story.

31.31 According to Plutarch in The Life of Solon, a contemporary of Plato by the name of Demades stated “Draco’s laws were written not with ink, but blood.”

32.32 See Reymond 1969, page 93.

33.33 Ibid., pages 106-107

34.34 Allen 2005, page 42.

35.35 Red linen is a garment worn to symbolize the birth of the Sun at dawn when its color is red which was reminiscent of the blood and amniotic fluid lost during birth with the placenta. For a general review of the topic, see URL: https://artofcounting.com/2010/08/16/the-red-looped-sash-an-enigmatic-element-of-royal-regalia-in-ancient-egypt-part-2/#more-435

36.36 Neyland and Seyfzadeh 2022, pages 141-143.

37.37 Reymond 1969, page 106-107.

38.38 Cf. Reymond 1969, pages 108-109.

40.40 In Egyptian mythology the heart was the seat of the mind.

41.41 see footnote 1 in Kurth 2014, page 323.

42.42 German loanword that encompasses the English words “original template.”

43.43 URL: https://www.docdroid.net/mgTxkdr/robert-beekes-etymological-dictionary-of-greek-vols-1-2-brill-2010-pdf#page=2

44.44 Beekes 2010, page 1490 entry referring to ταλάσσαι on page 1446: English “to endure,” “to tolerate,” “to bear.”

45.45 “with” in the German translation is added as a clarification but is not written in the hieroglyphic version, i.e. there is no ḥnꜤ.

This is an excellent article, including some new data about Egyptian myth. Thank you.

Well said. Rather than endless argument and speculation of physical and geological proxies found throughout the land of Egypt, examine instead what the Egyptians themselves said of their roots and origins, recognizing the linguistic migration of their telling over the vast timespan of this great civilization.

Secondly, this quest to pierce our amnesia is ultimately not about Lost Civilizations, it is about Lost Knowledge Systems; the most frail of human artifices!

Readers may find my commentary about Plato of interest – in this essay which is one of the chapters in my book: Unveiling Genesis: Mysteries of the Rootraces and Cycles. It is the in depth companion to my documentary: The Hidden History of Humanity. (See Youtube) https://esotericastrologer.org/?articles=time-history-re-establishing-esoteric-chronology-in-world-history

Graham (whose work I respect), invited me to publish this article on his website almost ten years ago, but it did not transpire as I did not want it edited.

Its disappointing that so many in the alternative archaeology field ignore the larger time cycles, keeping history closeted in a tiny 12,000 or 24,000 year cycle – not understanding the esotericism and veiled references in the Mystery Teachings.

AT THE DEEPEST PART OF ATLANTIC OCEAN ARE CITIES WITH PYRAMID LIKE TEMPLES, ONE SEEMS LIKE METAL-CAPPED based on sonar images.

https://www.scribd.com/document/678948729/Codex-Singularity-Search-for-the-Prisca-Sapientia

The quotes from these passages mentioned are explained in a lot of detail in my 400-page presentation at various places: scribd dot com/document/678948729/Codex-Singularity-Search-for-the-Prisca-Sapientia:

Timaeus 27d-28a

Timaeus 37d

Timaeus 34e

Critias 113c-d

Edfu vi 234 13

Critias 121a b

Also, the shape of Atlantis has symbolism that no one ever talks about as well. But yeah, I’ll be added these quotes to the presentation.

Excellent article, thank you….

Much praise. Interpreting ‘time’ and ‘not time’ really got me…and then the ring part with pictures with red pen n’ stuff on the Egyptian hieroglyphs yeah, I can read this because of your highlights and coordinating text. Thank you.