Ancient child’s bones deepen mystery of enigmatic human relative

Teeth and skull fragments found in the maze-like recesses of a South African cave fuel debate on how Homo naledi lived—and whether it disposed of its dead.

Wedged in a narrow crevice about 150 feet underground in South Africa's Rising Star cave system, Becca Peixotto squeezed between the rocky walls to work her way around a bend. Inch by inch she wriggled her body through the twisting passage, turning nearly upside down to reach a small ledge where a scientific treasure awaited—the teeth and bone fragments of a child who lived more than 240,000 years ago, an enigmatic human relative known as Homo naledi.

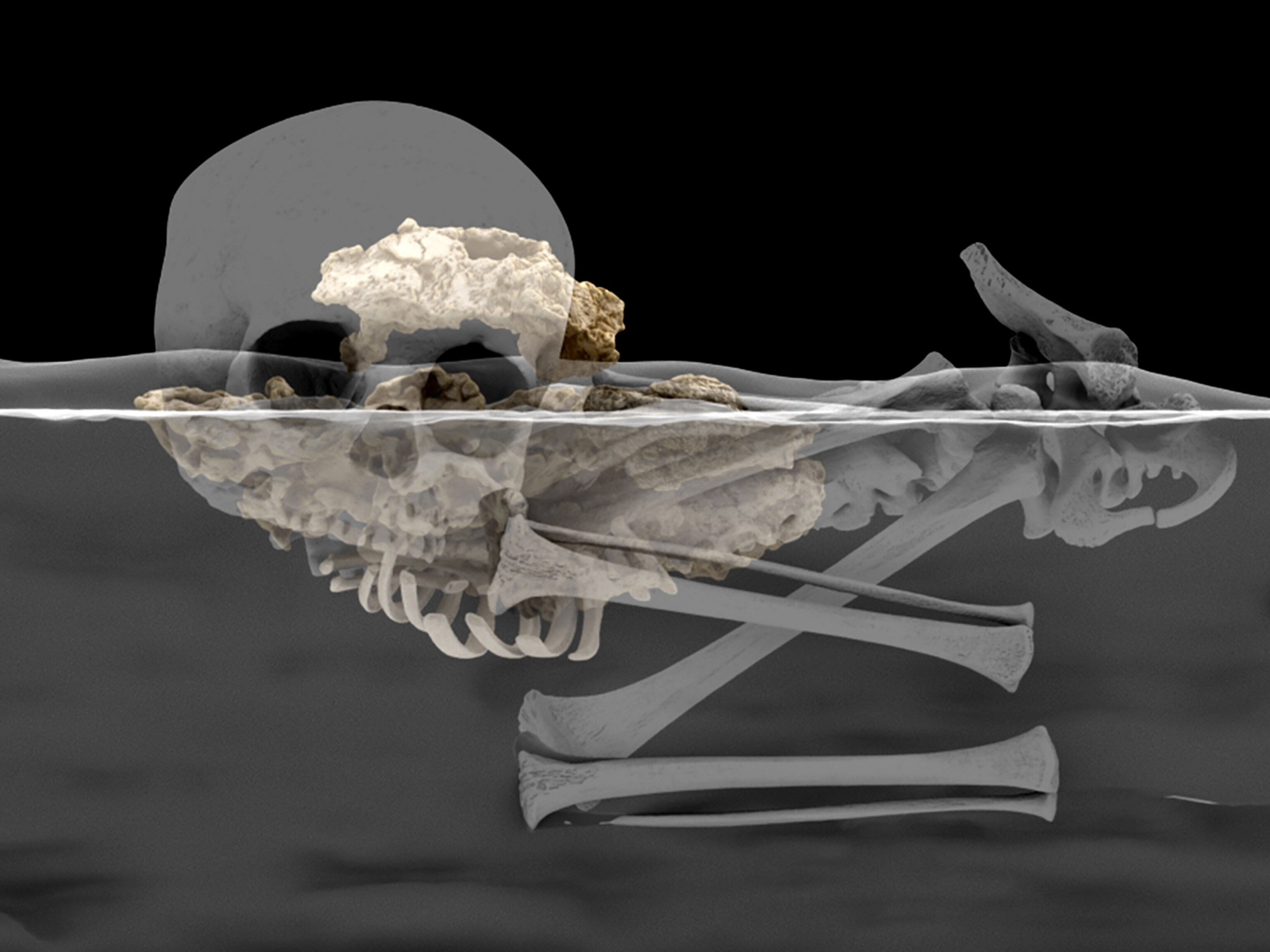

The find adds to nearly 2,000 bones and teeth of H. naledi recovered from Rising Star since cavers stumbled upon the first fossils in 2013. The remains of the child—estimated to have died between four and six years old—include six teeth and 28 skull fragments.

None of these discoveries have come easy, thanks to terrifying vertical drops and squeezes so tight that cavers must exhale to compress their rib cages. But the recent contortionist moves required by Peixotto, an archaeologist at American University, Washington, D.C., and her team members were some of the most challenging yet.

The labyrinthine venture to discover the remains of the child, nicknamed "Leti" after the Setswana word for lost one, underscores a nagging question about these mysterious human relatives: How and why did they venture so deep into this dark, twisting cave?

"No one involved in this had any expectations that we were going to find naledi bones in these situations," says John Hawks, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. "We're pushing into places that are meters and meters down impossible passages."

The child's discovery, described in a new study published in the journal PaleoAnthropology, was part of an effort in 2017 and 2018 to explore the deepest reaches of the cave. The team mapped more than 1,000 feet of new passageways and described the maze-like system in a second study. The work revealed only one entrance from the wider cave system into the Dinaledi subsystem, where most H. naledi remains have been found. The latest remains are the deepest yet found in the subsystem, deposited more than a hundred feet from its opening.

The discoveries hint that the remains may have been deliberately brought in by other H. naledi as a way of intentionally disposing of their dead, the study authors suggest. "We can see no other reason for this small child's skull being in an extraordinarily difficult to reach and dangerous positioning," said leader of the Rising Star Expedition Lee Berger, a paleoanthropologist at South Africa’s University of the Witwatersrand and a National Geographic Explorer at Large, at a press conference about the find.

Yet some scientists who were not part of the study are not yet convinced. Whether H. naledi carried their dead into the cave holds great significance for paleoanthropologists and archaeologists. Such intentional treatment of the deceased implies a level of cultural complexity once thought to be unique to our species.

"Our reaction to death, our love for other individuals, our social ties to them—how much do they depend on being human?" Hawks wonders.

The geologic jungle gym

H. naledi's perplexing mix of modern and ancient features sent scientists buzzing after the species' discovery was announced in 2015, showing human evolution is more complex than once thought. But one of the most astounding things about these short-statured hominins is just how difficult their remains have been to recover, and thus how difficult it must have been for them to venture so deep into the cave.

The first excavation team in 2013 consisted of six scientists, all women who were expert cavers and—importantly—small enough to fit through the cave's geologic jungle gym. Over the years, expeditions that were funded in part by the National Geographic Society have pieced together at least 20 H. naledi individuals, 15 of whom were found in a single chamber in the Dinaledi subsystem.

Such concentrations of bodies are often the result of a so-called "death trap," an underground cavern that opens to the surface where unsuspecting animals or people can fall in. But these traps kill a variety of animals, such as the menagerie found inside South Africa's Malapa cave, while the vast majority of bones in Rising Star are exclusively H. naledi.

Many other explanations for how the remains' ended up in the cave also fall short, according to the study team. It’s unlikely that carnivores dragged H. naledi into the cave because the bones bear no signs of teeth marks. The remains also don't seem to have been washed into the cave by water, since some body parts were found nearly intact, including a hand with the bones arranged as they would be in life: palm up, fingers curled inward.

Yet entry into the cave would have been perilous, especially with a dead body in tow. Close inspection of the system's only point of entry suggests there were two ways down during the time of H. naledi: a 40-foot, near-vertical drop known as the chute, or a network of barely passable crevices in one of the chute's walls.

The team initially proposed the H. naledi were disposing of their dead down the vertical drop leading into the chamber. But additional excavations revealed three sites, including the newfound child, that lay deeper in the cave.

"These are places that Homo naledi bone material could not be unless Homo naledi was in this subsystem, which means living Homo naledi were coming down the chute and entering this cave," Hawks says.

A cloud of questions

Other scientists, however, aren't yet convinced. The mapping and newfound bones do "not yet demonstrate that the remains must have been deposited deliberately by other humans," Paul Pettitt, an archaeologist at Durham University, writes in an email. But he adds that the latest find "makes it more likely."

He and other researchers suggest there are still alternative explanations that need to be ruled out. Perhaps the hominins were using the caves somehow and died there, says Aurore Val, a postdoctoral scholar at the University of Tübingen.

She points to baboons, who often spend their nights—and sometimes die—in caves. The dead baboons tend to be very young or old, and they die from a variety of natural causes such as disease, she says. In a recent study, Val and her colleagues found a similar spread of young and old among the remains of H. naledi in Rising Star and baboons at Misgrot cave, also in South Africa. "I'm not saying we solved the problem," Val says. "But I think it's worth exploring."

More detailed work is also needed to thoroughly document the geology of the cave and how it has changed through the millennia. And dating of Leti and other newfound fossils could also help pin down what the cave was like when the hominin remains were deposited, says Andy Herreis, a paleoanthropologist and geoarchaeologist at La Trobe University in Australia and National Geographic Explorer. "Caves are complex places," he writes in an email. "Passages open up and entrances collapse in through time."

While the cave has changed somewhat, including rock falls and the narrowing of some passages from the buildup of mineral deposits, the team's past analyses suggest the primary structure of the Dinaledi subsystem has remained fairly stable for hundreds of thousands of years, says study author Marina Elliott, an anthropologist at Simon Fraser University who led the cave excavations between 2013 and 2019.

Yet the debate will surely continue. Confirmation that H. naledi were braving the cave's winding passages to dispose of their dead would mark a vast shift in thinking for many scientists. Homo sapiens are the only living species that deliberately bury their dead, though some Neanderthals may have also engaged in such practices.

Perhaps other hominins deliberately disposing of their dead shouldn't be so surprising, Elliott says.

"As humans, we really like to feel special, and we really don't like it when other species kind of encroach on that," she says. But many traits scientists once considered defining features of Homo sapiens, such as toolmaking, have since proven to be shared with other hominins and primates.

Elliott acknowledges that many questions remain unanswered, and the pair of new studies seem to deepen the mystery. "But that's obviously good," she says. "That gives us lots to work on."

The National Geographic Society, committed to illuminating and protecting the wonder of our world, funded Explorer at Large Lee Berger's work. Learn more about the Society’s support of Explorers.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

Science

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

Travel

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- On the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migrationOn the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migration

- Everything you need to know about Everglades National ParkEverything you need to know about Everglades National Park